Sally Murphy's Blog, page 56

July 29, 2015

A Photo Haiku

This spider gave me a fright today, as I tried to hang out the washing. It’s a golden orb. Harmless, but still scared me. Later, though, it inspired a haiku.

July 20, 2015

Got a minute? Social Media in less than 60 seconds

If you’re a writer or illustrator, you have probably heard that you need to use social media to promote yourself and your books. But if you’re anything like me, you are balancing your creative work with promotion, with raising a family, with reading, with day jobs and author talks and maybe some exercise or some housework or… My point is, you may well feel that social media is just one thing too many. And it can, if you let it, sap a lot of your time. There is no limit to how much time you could spend on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Instagram (have I missed some? I’m sure I have!)

But we’re living in a digital world, and the fact is, the things you do on social media can and will attract readers and purchasers, as well as getting your name known for potential speaking gigs.

The good news is, that once you have set up accounts on your chosen social media platforms, there are lots of things you can do in a minute or less that keep your feed ticking over.

Take a photo. Your desk, your bookshelf, a cloud or a bird you saw on your morning walk, your

cat, your dog, your book cover, you. Add a sentence or two and you have a perfect post for twitter, Instagram or facebook.

cat, your dog, your book cover, you. Add a sentence or two and you have a perfect post for twitter, Instagram or facebook.Share a link. Anything you find interesting online, someone else will find interesting too. Again, add a line or two explaining what the link is for, and pop in twitter or facebook. If you struggle to find interesting stuff, set up a google alert, or check out Feedly.

Share someone else’s content. Retweet a clever tweet, share a facebook post, repin a pin. Again, adding a sentence or two of your own shows why it’s significant to you.

Interact by liking or commenting on someone else’s status. Start a conversation on twitter, facebook or Instagram.

Join in a challenge or meme. There are lots of such challenges on both Twitter and Fecbook that challenge you to post something every day for a set period (such as the #postitnotepoetry challenge on Twitter in February). Joining up gives you one topic to post about every day for that time. Some ask for a photo each day, others a poem or piece of writing.

You’ll notice that most of these are not about directly promoting yourself. Rather, you are building relationships, with the two fold benefit that when you do promote it becomes more meaningful and effective, and at the same time you are having fun and making new friends. Perhaps that’s the topic for another blog post.

A minute is not a lot of time, and these five things can each be done in less than a minute. Social media doesn’t have to be an all-day every day proposition. In less than the time it’s taken you to read this post, you can tick promotion off your to-do list each day.

(PS. If you want to see what I’m doing on Social Media, you can find me on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Instagram ),

July 16, 2015

Poetry Friday: A Classroom Poem

It’s almost the end of the school holidays here in my part of the world. For two weeks kids, including my own, have had a beak from school – but come Monday, they’ll be heading back.

So, I thought for Poetry Friday I’d share a school poem, which I wrote a few years ago as part of a set of teaching notes. First, here’s the poem:

Here’s me, trying to get a poem to appear by some sort of magic :)

Writing a Poem

Kids crying

kids sighing

kids chewing pens

or writing.

Giggling

and wriggling

and impatiently jiggling.

Passing notes

scrumpling and crumpling pieces of paper

as the clock tick tock ticks

and Miss Imms paces the room

waiting for our poems to appear.

(Copyright Sally Murphy)

This poem was written to demonstrate a simple way to write a poem – in this case, the poem started with a list of observations. The notes, including the poem, are freely available online here.

July 14, 2015

Tips for Writing Issues-Based Stories

So I’ve been talking lately about how I’m okay with my books making people cry, but how I’m concerned when they are classed as issues books first and foremost, so I thought perhaps I might talk a little about how I as a writer I ensure that the issue doesn’t overshadow the story. Here are my tips for planning and writing an issues-based story

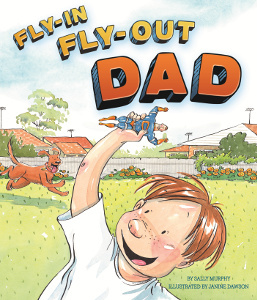

Try not to start with an issue. If you are planning to write a book about bullying, or about cancer, or about environmental degradation, then consider writing nonfiction. If it must be fiction, then work hard to ensure that the issue is explored through the story, rather than the story taking a back seat to lists of information. When I wrote Fly-In Fly-Out Dad I knew I wa

nted to write about a family living the FIFO lifestyle, but I also knew that I couldn’t explore very aspect of that. Instead I focused on one family’s story.

nted to write about a family living the FIFO lifestyle, but I also knew that I couldn’t explore very aspect of that. Instead I focused on one family’s story.Build characters. Whatever the issue you are exploring, the character is key! Without a strong character at the heart of the story, readers just don’t care. In Fly-In Fly-Out Dad I chose one child, Tiger (a family nickname – his name is actually Riley), and shared his version of the FIFO lifestyle. In 1915 I chose one soldier, Stanley, and followed his wartime experiences, and in my verse novels, I have always started with a character long before I knew what their particular issue was.

Build plot. Every plot needs a conflict, and a resolution. And, along the way, ebbs and flows. In Fly-In Fly-Out Dad Tiger hopes Dad will stay home this time, but we don’t see how that resolves until the end. In the meantime we see good times, as Dad tells of his time on site, and as the family spend time together. But, every now and then, Tiger remembers that Dad might leave again. This keeps the tension mounting, and reminds us of the conflict.

Don’t try to cover every aspect or possibility of the issue. In Fly-In Fly-Out Dad I only cover one swing (the rotation of time on site and at home – in this case 3 weeks on, 1 off), one workplace (a mine site ‘up North’), and just one family set up (Dad away, Mum and two kids at home). Trust children that they can relate it to their own experience.

Don’t try to cram fiction with facts. The facts should appear naturally. Rather than saying ‘Dad

sleeps in a donga, which is a transportable building….’, I have Dad telling the family about the donga, and the illustration helps here. In 1915, which is historical fiction, I worked at including dates, important battles and so on, into the action, rather than listing them. As a result, we see how these events impact the characters rather than simply being told that they happened. Show don’t tell.

sleeps in a donga, which is a transportable building….’, I have Dad telling the family about the donga, and the illustration helps here. In 1915, which is historical fiction, I worked at including dates, important battles and so on, into the action, rather than listing them. As a result, we see how these events impact the characters rather than simply being told that they happened. Show don’t tell.Don’t tell readers how to feel. It’s a story, not a sermon. In Fly-In Fly-Out Dad readers can see that Tiger misses his dad, and that he is sad about him leaving. They may feel the same way, and may benefit from seeing their own situation reflected in a book, opening up opportunities to talk about their own lives. But they may not feel sad. Their family life might work just fine. And they shouldn’t feel that Tiger’s experience has to be theirs, which leads me to my final point.

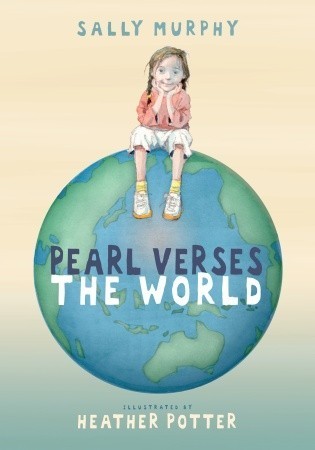

Issues fiction works best when it is written for a wider audience than those facing the situation. When you make the story interesting for people who haven’t had that experience, it also seems to work better for people who have. You don’t have to have a FIFO dad (or mum) to connect with Tiger’s family. You don’t have to have lost a grandmother, to connect with Pearl. And that’s because the character comes before the issue (see points one and two above).

I started with bemoaning being termed an issues writer. To be honest, I’m proud of writing about issues which impact young people. But I hope that this works because my first aim is to write stories which they enjoy, about characters they can connect with.

July 12, 2015

On Issues and Taste (and salad)

The other day I posted about my books making people cry and how I’m okay with that. But I have to admit that when I’m classed as someone who writes sad books or issues based books, I sometimes feel a bit frustrated.

I certainly explore some tough issues and some sad situations, but I think when we use terms like ‘issues-fiction’ or label a story as being about a particular issue, we can do the book a disservice.

When a kid picks up a book, they are, on the whole , looking to be entertained. As they read, they may also learn things. That’s fine. But if we suggest that they should be reading a book just because it deals with a particular issue (childhood cancer, or dementia, or the horrors of war, for example), we risk alienating them before they even start.

It’s a bit like healthy food: telling kids they should eat a healthy salad ‘because it’s good for them’ is, on the whole, less successful than telling them it’s yummy. And definitely less successful than if it actually is yummy. The kid who enjoys the first mouthful of salad is far more likely to keep eating, and get the health benefits along with the full tummy and the enjoyment of the meal.

So, too, with a book. Saying: You should read this book because it deals with a weighty issue you need to know about is a turn off. You should read this book because it’s funny, or exciting, or interesting is more enticing. But most successful of all is when a kid samples the book (through a good blurb, or browsing the opening pages, or even being read a little bit of it in class) and wants to know what happens next.

To me, character and plot come waaaaaaaay before any issue. But that’s the topic for another blog post (or two). In the meantime, my point is this: as a writer of fiction, story is always key; and if you are an adult offering books to kids, don’t just tell them it’s good for them. Tell them why they’ll like it, or better still, give them a chance to taste it for themselves.

July 10, 2015

What to Do When Your Child Cries Over a Book

So, I posted about a child crying over Fly-In Fly-Out Dad and how I think it’s fine when a child cries reading a book. But then of course I got to thinking about this, and wanted to talk about it a little more. Because just going ‘yup, that’s fine’ is not going to work in every case.

Firstly, consider the child’s situation. In the example of a child crying when he hears Fly-In Fly-Out Dad because he too has a FIFO dad, who just happens to have left home that morning, the correlation between real Dad leaving and fictional Dad leaving, is a pretty fair indicator of why the child might be crying. In this case, there is an opportunity for the child to express his sorrow for his own situation, and for the adult (in this case a teacher) to offer sympathy and comfort, as well as for other children to perhaps be offered an insight into what the child is going through.

Firstly, consider the child’s situation. In the example of a child crying when he hears Fly-In Fly-Out Dad because he too has a FIFO dad, who just happens to have left home that morning, the correlation between real Dad leaving and fictional Dad leaving, is a pretty fair indicator of why the child might be crying. In this case, there is an opportunity for the child to express his sorrow for his own situation, and for the adult (in this case a teacher) to offer sympathy and comfort, as well as for other children to perhaps be offered an insight into what the child is going through.

Secondly, consider how upset the child is. Think about when you yourself last read a sad book or watched a sad movie. Usually you cry, then smile, then feel better. You might continue to think about that book, even discuss it with other people, but you don’t stay sad for hours or days or weeks afterwards. So, if a child cries a little at a sad book, then moves on, don’t fret. But if the child cries for a prolonged period of time, chances are it may not be about the book at all, or the issue raised in the book is raw for the child in some way. Offer comfort but also consider further what it is that really upsetting the child and what can be done about it. If you are a teacher, for example, you might need to let the child’s parents know how upset the child has been, and as a parent you might discuss with your child what has upset them so much. Start a dialogue.

Thirdly, let your child see your own emotion. If a book makes you sad, too, don’t be scared of reading in front of children and letting them see that crying is not a bad thing. I used to avoid reading the sad parts of my stories during appearances. I worried I might get teary in front of the kids, so I read them  all the funny,uplifting bits. Then I realised that I might be giving the wrong impression of my books, and that children might be made more sad when they read the books for themselves. So I got brave, and I read the scenes where Pearl and where John get bad news, and yes, my voice broke and I got teary. And I survived, and kids still read my books afterwards.

all the funny,uplifting bits. Then I realised that I might be giving the wrong impression of my books, and that children might be made more sad when they read the books for themselves. So I got brave, and I read the scenes where Pearl and where John get bad news, and yes, my voice broke and I got teary. And I survived, and kids still read my books afterwards.

Finally, if you are an adult offering potentially sad books to children, do stop and think about the child’s situation before you give it to them. For example, Pearl Verses the World deals with a dying grandmother. The book may be too raw for a child who is grieving a similar recent loss, but they may enjoy it down the track. Read the book for yourself, and think about the particular child. I think it is possible for a book to be too sad for a specific child, just like a scary book might be too frightening for some children but not others.

The world needs sad books (with uplifting endings) because tough stuff happens in the real world. Not every book should make a child cry, but if sometimes one does, that’s okay.

July 9, 2015

Poetry Friday: Ducks

Among the other wildlife that abounds in my suburb, there are many many ducks. I love seeing them on my walks, and out my front window, though I’m less keen on seeing them when I’m driving. I have to admit it puzzles me that they insist on walking on roads, when they could fly! Fortunately, most drivers slow down and give them to cross.

Anyway, because it’s Poetry Friday, and because I’ve been thinking a lot about these ducks, here’s a favourite duck poem, from Ogden Nash, and a favourite duck photo that I took a while ago.

The Duck

by Ogden Nash

Behold the duck.

It does not cluck.

A cluck it lacks.

It quacks.

It is specially fond

Of a puddle or pond.

When it dines or sups,

It bottoms ups.

What I love about this poem is that, like so much of Nash’s verse, it makes me smile. The humour in the choice of rhyme, and the duck-like flow of the short sharp lines never fails to bring a grin.

Poetry Friday today is hosted at The Logonauts. There you will find links to lots of other poetry goodness.

July 8, 2015

It’s Okay to Cry

When my daughter in law told me that Fly-In Fly-Out Dad made a six year old student cry, I have to admit I was surprised. It’s not that I’m not used to hearing that my books make people cry – after all, with dying grandmothers, kids with cancer, terrible accidents and war featuring in my books, I know they are prone to inducing tears in readers, just as they did in me.

But Fly-In Fly-Out Dad is a picture book. And it has a superhero! It’s bright and colourful and aimed at little kids. I don’t want to make them cry, do I?

And then, of course, I realised that of course it will make some people (children and adults) cry, for just the same reason as it made me cry writing it, and in the same way those other books make some people cry.

The good news Is, it won’t make everybody cry. It really won’t. But, if you are six years old, and your own father is a FIFO worker, and has just flown back to work, and then your teacher shares the book with you, you might cry because you empathise with Tiger, the boy in the book. You might cry because the book has given you permission to admit that it’s hard seeing Dad leave after a spell at home. You might cry because, like Tiger, you decided to be brave when Dad said goodbye, but now that he’s gone you want to admit that you wish he didn’t have to.

The good news Is, it won’t make everybody cry. It really won’t. But, if you are six years old, and your own father is a FIFO worker, and has just flown back to work, and then your teacher shares the book with you, you might cry because you empathise with Tiger, the boy in the book. You might cry because the book has given you permission to admit that it’s hard seeing Dad leave after a spell at home. You might cry because, like Tiger, you decided to be brave when Dad said goodbye, but now that he’s gone you want to admit that you wish he didn’t have to.

Some adults are scared by books that make kids cry. Personally, I think they’re wrong. If a book encourages a child to explore their emotions,provides opportunities to discuss them, andante the same time perhaps explains parts of the situation they may not understand (in this case, what Dad actually does when he’s away), then that’s a good thing.

Adults cry when reading books. And we go back for more. Why shouldn’t kids be able to do that too?

January 23, 2014

Poem: Selfie

January 22, 2014

A Micro Story: In Trouble

<!--[if gte mso 9]>

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-AU

X-NONE

X-NONE