Benjamin A. Railton's Blog, page 95

October 4, 2022

October 4, 2022: Bad Presidents: Rutherford B. Hayes

[October 4thmarks the 200thbirthday of Rutherford B. Hayes, a good-looking young man who went on to be a very bad-governing president. So this week I’ll contextualize Hayes and four other under-remembered bad (in the least good sense) chief executives, leading up to a weekend post on the worst we’ve ever had.]

On why the “corrupt bargain” was just the tip of the badness iceberg.

I’ve written multiple prior posts focused directly on the presidential election of 1876, to my mind the single most destructive in the nation’s history (well, it used to be, anyway). Historians apparently now disagreeon whether and how the “corrupt bargain” that was long believed to have overtly resolved that controversial and contested election took place, and to be sure such details are important and worth continuing to investigate (and have a great deal to us about such deeply relevant topics as election integrity and protecting democracy). But at the same time, we can’t miss the forest for the trees, and I believe that the forest here is inarguable: whatever the precise mechanisms and machinations by which Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes bested New York Governor Samuel Tilden to become president in 1877, one of Hayes’ first actions was to end Federal Reconstruction, abandoning the former Confederate States—and more precisely the millions of African Americans living in them—to the rule of white supremacist, neo-Confederate, violent extremist domestic terrorists.

If Reconstruction was indeed (as historian Eric Foner defines it in his magisterial book) “America’s unfinished revolution,” then no single figure was more responsible for the unfinished part than Rutherford B. Hayes. That becomes even more obvious and even more frustrating when we compare Hayes to his predecessor Ulysses S. Grant, for whose impressive and frankly under-remembered support of Reconstruction I have recently made the case in this space. To follow up my point in yesterday’s post: Hayes wasn’t responsible for all the conditions and contexts around this contested and conflicted moment (and from what I can tell his personal perspective included genuine concern for African Americans in the post-war South); but his choices and actions, his emphases and policies, could unquestionably have followed much more fully in Grant’s footsteps and continued the federal fight for Reconstruction and African American rights. That he did not do so would, to my mind, be more than enough to make him worthy of this series on bad presidents.

But the end of Federal Reconstruction is in fact not the only thing which earns Hayes a spot on this less than desirable list. In the summer of 1877 the first truly national labor action took place, the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, which saw strikes and protests by railroad workers in West Virginia, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, and many other cities. Once again, Hayes was in no way responsible for the conditions and contexts of these conflicts—but as president, he had a fundamental choice to make about how the federal government would respond to them. He chose (in response to requests from governors such as West Virginia’s Henry M. Mathews, but the choice lay with Hayes nonetheless) to send in federal troops to suppress the strikes and protect property, the first time such soldiers had been used to achieve those anti-labor goals. In so doing, Hayes helped create a hugely destructive precedent for such official and violent federal opposition to strikes, labor actions, and the labor movement more generally, one that would significantly affect that movement and all of American history for decades to follow. Not so good, Rutherford; not so good at all.

Next bad president tomorrow,

Ben

PS. What do you think? Other baddies you’d highlight?

October 3, 2022

October 3, 2022: Bad Presidents: James Buchanan

[October 4thmarks the 200thbirthday of Rutherford B. Hayes, a good-looking young man who went on to be a very bad-governing president. So this week I’ll contextualize Hayes and four other under-remembered bad (in the least good sense) chief executives, leading up to a weekend post on the worst we’ve ever had.]

On a bad president who helps us resist destructive narratives of historical inevitability.

One of the more complicated but more crucial arguments at the core of my new book project concerns the importance of resisting the idea that history was always, inevitably going to unfold in the ways that it did. The specific context for that argument in this project is the hugely frustrating way in which Irish Americans, themselves the subject of pretty intense xenophobia and discrimination in the early 19th century, became by the mid- to late-19th century one of the communities most consistently and fully upholding white supremacy in America, often through violence like the New York City draft riots, the Rock Springs massacre, and many more events. Moreover, the Irish American immigrant on whom that half of the book focuses, labor leader turned face of the anti-Chinese movement Denis Kearney, embodies that shift even more blatantly: not only as an immigrant who became a leading anti-immigrant voice, but also as someone who briefly fought to protect San Francisco’s Chinese American community and then became its most aggressive adversary (for more, read the book!).

Those histories happened, and it’s certainly crucial that we remember that they did, not least so we can explore and understand why and how they did. But I believe a corollary goal is to recognize that they could have gone differently, that history is contingent upon countless actions and choices, that individuals, communities, and the nation as a whole have distinct paths in any and every moment (and thus in our own). Otherwise, if we give in instead to a sense that the way our history went was inevitable, it becomes almost impossible to resist pessimism or even fatalism, to imagine the possibility of such alternative paths, such choices and changes, in our own moment. One of the most striking historical tests of this perspective has to be the Civil War—not only because in hindsight all the events that led up to it seem so inevitable (and perhaps rightfully so, since despite the war’s tragedies and horrors its most crucial outcome was the end of slavery), but also and especially because even in the contexts of their own era it’s quite difficult to see how things could have (or, again, perhaps even should have) gone differently.

There’s a lot more to those questions and ideas than I can address in one blog post, of course. But I think it’s pretty important to note that the president whose term directly preceded and in many ways precipitated the Civil War, James Buchanan, wasn’t just a bystander to unfolding histories. In his March 1857 Inaugural Address, Buchanan called “the territorial question” (whether newly admitted territories would be slave or free states, that is) “happily, a matter of but little practical importance,” as the Supreme Court was about to resolve the issue “speedily and finally.” When that truly awful 1857 Supreme Court decision did not in fact resolve any of the issues or debates around slavery, Buchanan took the further step of putting the full force of the presidency behind admitting Kansas to the United States as a slave state, directly exacerbating the unfolding conflicts and violence in that territory. Buchanan wasn’t responsible for any of those issues, but each of those statements and positions, actions and policies, he and his administration both supported the slave South and fueled the fires that would become a full conflagration by the end of his disastrous term. None of that was inevitable, making James Buchanan a very bad president indeed.

Next bad president tomorrow,

Ben

PS. What do you think? Other baddies you’d highlight?

October 1, 2022

October 1-2, 2022: Kelly Marino’s Guest Post: The “American Queen”: “Sweetheart” Bracelets, Jewelry Trends, and the World Wars

[Dr.Kelly Marino is a Lecturer of History at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, CT and the Coordinator of the Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies program. Her research is on Modern US History, and she is writing a book about college students, alumni, and the women's suffrage campaign.]

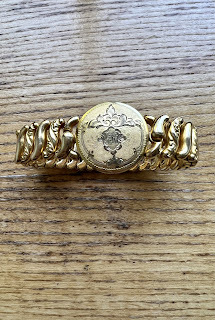

[This is a D.F. Briggs Carmen Bracelet. All others stamped Pitman and Keeler American Queen.]

Today, if you search the popular artisan and craft website Etsy.com, you will come across over 4 million hits for the term “personalized”. Consumers can add initials or a special message to just about any item from jewelry to pens and pencils. Monogramming and personalized gifts have become an entire retail genre with stores devoted to producing these products. Many large retailers even offer the option of personalization for a fee with in-store and online orders. Personalized jewelry, a fad that remains popular during the holiday gift-giving season especially, dates back centuries, pushed forward during sentimental times in the Victorian period and the World Wars. In the United States, one piece of personalized jewelry that has had a significant influence on fashion history is the monogrammed expandable bracelet.

Often gold-plated or rolled gold sterling silver with an elastic chain, the popular early twentieth-century women’s expansion bracelet came in many styles, including a solid embossed or engraved centerpiece in a circular, oval, rectangular, or square shape adorned by cameo, jewels, mother-of-pearl, or rhinestones. Adult bracelets were only a few inches wide at rest but appealed to women of different sizes as they could be easily stretched to fit almost any wrist. During World War I and World War II, these fashionable yet versatile bracelets were particularly popular among Americans in the US, becoming a common keepsake for soldiers to give to their girlfriends, wives, daughters, sisters, mothers, or grandmothers as a token of remembrance. The bracelets significantly influenced jewelry and fashion trends, with metal adjustable expansion wristbands becoming mainstream in inexpensive watchmaking by the 1900s.

Queen Victoria’s Influence

The concept of expansion bracelets was first conceived and popularized during the Victorian era. As an influential role model in Europe and the United States, Queen Victoria of the British Empire shaped jewelry trends. Her tastes spurred three distinct phases in jewelry making as women tried to copy her looks: the “Romantic Era” (1837-60), “Grand Era” (1861-1880), and “Aesthetic Era” (1880-1901). The “mourning jewelry” that the queen wore during the Grand Era while grieving the death of her husband, Prince Albert, was especially influential. Mourning jewelry was frequently gold-toned or dark colored, personalized or monogrammed, and given as a gift in remembrance of a loved one. It could also include a locket or compartment to store a photograph or strands of the deceased’s hair. These trends resonated into the twentieth century: personalized or monogrammed pieces remained popular, as did the tradition of wearing jewelry to remember a loved one, particularly in times of war.

The Rise of the “Carmen” and “American Queen” Bracelets

Cosmopolitan Americans copied European fashions to appear more advanced, cultured, and stylish. At the turn of the twentieth century, the United States was still establishing itself as a viable and credible nation on the global scene, and women did not want to lag behind their sisters across the Atlantic. Jewelers imitated international styles and adapted what they learned to innovate their fashions. Expansion bracelets, for example, were first created in Massachusetts, with excitement for the new accessory spreading from New England to the rest of the nation. Initially produced in large numbers in Attleboro, MA at the turn of the twentieth century, the bracelets were marketed as adornment for babies; in light of the product’s success, however, marketing was expanded to young girls and, eventually, adult women.

It is difficult to identify all of the various companies that produced these bracelets as some did not feature a maker’s mark. The earliest and largest producers included the D. F. Briggs Company, perhaps the first developer of the bracelets, as well as the Pitman and Keeler Company. The D. F. Briggs Company was established in 1882 when Briggs opened a shop to create metal items, such as bars, chain trimmings, eyeglass and vest chains, plate swivels, rings, and watch materials. As the company expanded and evolved, it began to produce new products, including expansion bracelets and other jewelry. Eventually, the company name was changed to Briggs, Bates, & Bacon Co. Their unique bracelets came to be known as “Carmen” (or “Carmelita”) bracelets, with one source citing Briggs’ daughter as the inspiration.

Also from Attleboro, McRae and Keeler (renamed Pitman & Keeler in 1907) produced its line of expansion bracelets, the “American Queen,” which were possibly the most popular version. Established in 1893, the company initially manufactured bracelets, compacts, and vanity cases. One of the best-selling designs (and subsequently hardest to find because of its enduring popularity) features a vibrant, heart-shaped gemstone in blue, green, purple, or red complemented by a rolled gold band and setting. The gemstone reflected light in the way a Swarovski crystal does today.

These bracelets grew in popularity across the early twentieth century as jewelry never fell out of favor, even in times of national hardship. Sporting an expansion bracelet remained a luxury that many women refused to give up despite periods of economic challenge and restriction, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s. A simple piece of jewelry, such as an ornate metal bracelet, was durable, and versatile, and could be added to a bland dress or another outfit to make it more stylish. During WWII, Pitman and Keeler even started making matching necklaces and bracelet sets in response to consistent demand. Companies were producing the bracelets nationally, in places like New York and Rhode Island, and internationally, in England. Massachusetts’ product was a widespread success.

“Sweetheart” Jewelry during the World Wars

To keep their bracelets selling as the twentieth century continued, jewelry manufacturers, including the two key New England companies, began marketing expansion bracelets and associated accessories in line with the growing “sweetheart” jewelry trend that had taken off during the world wars. Sweetheart jewelry was a genre of jewelry designed for soldiers to buy for their female loved ones to wear as a token of connection and remembrance while they were serving overseas. Sweetheart expansion bracelets worn by young women were aesthetically pleasing and also a symbol of patriotism and pride, declaring to all who saw that the wearer’s loved one was in service. Popular expansion bracelet styles during the world wars included a monogrammed version with the receiver’s or couple’s initials as well as a heart-shaped locket version for photo storage.

Although interest in these bracelets peaked during World War II, they continued to be produced and sold in various capacities into the 1950s and, in such forms as rhinestone and faux diamond bracelets, even the ‘60s and ‘70s before trailing off in the late twentieth century. Today, this New England product remains a desirable and wearable fashion find among collectors and vintage jewelry enthusiasts who still buy and sell them at antique stores and estate auctions. The more ornate bracelets are increasingly difficult to find, especially sets with matching necklaces or in the original box. However, they still surface for sale on the Internet, are passed down in families, or are discovered in vintage jewelry boxes. Personalized jewelry given as gifts to loved ones during important moments remains a popular tradition as does the use of expandable bands in jewelry making that can be manipulated to fit wearers wrists of various sizes. Watches in particular are still sold using the same concept and similar design as the sweetheart bracelets even today.

Beyer, Suzanne G. "The Legacy of the Original Expansion Bracelet." Jewelry Making Journal (blog). Rena Klingenberg, accessed September 2, 2021. https://jewelrymaking

journal.com/the-legacy-of-the-original-expansion-bracelet/.

Collectors Weekly. "Vintage Sweetheart Jewelry." Collectors Weekly, accessed September 6, 2021. https://www.collectorsweekly.com/costume-jewelry/sweetheart.

Kovel, Ralph, and Terry Kovel. “‘Sweetheart’ Jewelry Was Serviceman's Gift: In the 1940s, Soldiers and Sailors Sent Heart-Shaped Pins, Pendants, Lockets and Bracelets Decorated with Military Emblems to their Loved Ones at Home.” Antiques. The Baltimore Sun. March 9, 1997. https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1997-03-09-1997068143-story.html.

LPRMGLOB. “Vintage Expandable Sweetheart Bracelet Gold Filled Expansion Bracelets Amercian Queen LaMode Locket Bracelet Pittman Keller Bates Briggs.” LPRMGLOB, accessed September 6, 2021. https://www.lprmglobal.com/index.php?main_page= product_info&products_id= 44964.

Maejean Vintage. 2017. “Vintage Jewelry Ads: Jeweler's Circular, June 7, 1911.” Maejean vintage (blog). February 16. https://www.maejeanvintage.com/blog/2017/1/13/antique-jewelry-advertisements-jewelers-circular-1911.

Teichman, Susan. “A Celebration of Unity, Sweetheart Jewelry from the World War II Era.” Cooper Hewitt. July 13, 2018. https://www.cooperhewitt.org/2018/07/03/a-celebration-of-unity-sweetheart-jewelry-from-the-world-war-ii-era/.

Thurston, Sarah. 2013. “Let Me Call You ‘Sweetheart’ – Patriotic Jewelry of the Wars.” Janvier Road (blog). July 29. https://janvierroad.wordpress.com/2013/07/29/let-me-call-you-sweetheart-patriotic-jewelry-of-the-wars/.

Vintage Dancer. 2017. “1940s Jewelry Styles and History.” Vintage Dancer (blog). May 30. https://vintagedancer.com/1940s/1940s-jewelry-styles/.

Ward, Tanzy. “Collecting Victorian Mourning Jewelry and Its Modern Historical Significance.” Collecting, Jewelry. Worthwhile Magazine, 2021. https://www.worthwhile-magazine.com/articles/collecting-victorian-mourning-jewelry-and-its-modern-historical-significance.

Zanathia. “Antique Victorian Era Mother of Pearl & Sterling Silver Base Sweetheart Bracelet.” Zanathia. 2021. http://danielleoliviatefftwrites.com/found-in-the-jewelry-box-blog/how-old-is-that-expandable-sweetheart-bracelet-in-your-jewelry-box.

[Next series starts Monday,

Ben

PS. What do you think?]

October 1, 2022: September 2022 Recap

[A Recap of the month that was in AmericanStudying.]

August 29: Fall Semester Previews: 19C African American Lit: For my semester previews I wanted to focus something I’m especially looking forward to in each class, starting with connecting 19C Af Am Lit to contemporary debates.

August 30: Fall Semester Previews: First-Year Writing I: The series continues with linking my First Year Writing class to the First Year Experience seminar all FSUI students now take.

August 31: Fall Semester Previews: Honors Lit Seminar on the Gilded Age: Why I keep coming back to the same subject and same concluding novel for this course, as the series teaches on.

September 1: Fall Semester Previews: American Lit II Online: Why and how I’m finally trying to do at the end of an online Am Lit II survey what I’ve always done in-person.

September 2: Fall Semester Previews: Adult Learning Classes: The semester previews conclude with something I’m trying for the first time in my two adult ed classes.

September 3-4: Other Fall Updates: But that’s not all I’ve got going on this Fall, so here are quick updates on my book in progress and a couple events you can be part of!

September 5: APUSH Studying: Mrs. Frankel: As my older son starts his year of APUSH, a series on contexts for that complicated course, starting with the wonderful teacher from whom I learned it.

September 6: APUSH Studying: The Evolving Framework: The series continues with two things I’d highlight about the controversial APUSH frameworks.

September 7: APUSH Studying: Flaws and Limits: Two fundamental flaws in APUSH & AP courses, and how the class itself can engage them, as the series studies on.

September 8: APUSH Studying: The American Pageant: A frustratingly telling textbook controversy, and what it’s not the whole of the story.

September 9: APUSH Studying: High School History Heroes: The series concludes with a quick tribute to just a handful of the many amazing high school history teachers I’ve gotten connected to!

September 10-11: Michael Walters’ Guest Post: Chaos, Order and Progress in the first North American Nation: My latest excellent Guest Post (although watch this space later today!)—share your own ideas for a Guest Post, please!

September 12: War is Hella Funny: Catch-22: In honor of M*A*S*H’s anniversary, a series on wartime humor kicks off with one success and one failure in Joseph Heller’s groundbreaking book.

September 13: War is Hella Funny: Hogan’s Heroes: The series continues with the vital importance of not judging a book by its cover (or a sitcom by its premise).

September 14: War is Hella Funny: Dr. Strangelove: How a satirical film can sometimes offer more historical clarity than history, as the series laughs on.

September 15: War is Hella Funny: Good Morning, Vietnam: Three competing yet ultimately intersecting layers to the hit 80s comedy.

September 16: War is Hella Funny: Tropic Thunder: The series concludes with whether the Hollywood meta-comedy is also a wartime meta-comedy.

September 17-18: War is Hella Funny: M*A*S*H: For the 50th anniversary of the TV show’s pilot, AmericanStudies takeaways from each of the three iterations of M*A*S*H.

September 19: Southern Storytelling: Fathers and Sons: For Faulkner’s 125thbirthday, a series on Southern storytelling starts with the multi-generational relationship at the heart of the Southern Renaissance.

September 20: Southern Storytelling: Thomas Wolfe: The series concludes with an ironically forgotten author who deserves to be remembered and read.

September 21: Southern Storytelling: Carson McCullers: Three compelling works by a hugely talented author lost far too soon, as the series reads on.

September 22: Southern Storytelling: Representing Katrina: Three exemplary stages in how storytellers in every medium have depicted a 21st century tragedy.

September 23: Southern Storytelling: Faulkner at the University: The series concludes with one ironic and one inspiring lesson we can take away from the bday boy’s UVA conversations.

September 24-25: Faulkner at 125: Digital Yoknapatawpha: But I can’t celebrate Faulkner’s birthday without a tribute to the best digital project on Faulkner from my favorite digital humanities scholar!

September 26: Asian American Leaders: Pablo Manlapit: A series on Asian American leaders kicks off with an early 20th century Filipino American labor activist.

September 27: Asian American Leaders: Yuri Kochiyama: The series continues with a few of the many reasons we should remember the influential activist and community leader.

September 28: Asian American Leaders: Patsy Mink: On the 20th anniversary of her death, three signature achievements in the amazing career of Patsy Mink.

September 29: Asian American Leaders: Lisa Wong: A telling story that reveals much more than just a 21st century leader’s initiative, as the series leads on.

September 30: Asian American Leaders: Michelle Wu: The series and month conclude with the 21st century Asian American leader who has inspired my son and me alike!

Guest Post later today,

Ben

PS. Topics you’d like to see covered in this space? Guest Posts you’d like to contribute? Lemme know!

September 30, 2022

September 30, 2022: Asian American Leaders: Michelle Wu

[On September 28th, 2002 the great Patsy Mink passed away. So this week I’ll AmericanStudy Mink and four other Asian American leaders, past and present!]

On one example of the worst of 2022 America and so much of the best when it comes to Boston’s exciting new mayor.

First things first: I’m never going to be able to write about Michelle Wu’s successful 2021 campaign for mayor of Boston with anything even vaguely approaching objectivity. Wu was the first political figure about whom my older son got really excited—his high school requires community service hours for graduation, and he’s a deeply committed young environmentalism and climate change activist so during the summer after 9th grade he began volunteering with the Environmental League of Massachusetts (ELM). ELM had endorsed Wu’s campaign, and much of his volunteering thus became canvasing and manning tables for Wu for Boston; he even had the chance to meet and chat with her after one such event in Roslindale (the Boston neighborhood where she lives with her family). To say that the election of Wu as mayor was a big deal in the Railton household would thus to be significantly understate the case, and we haven’t been the slightest bit disappointed as she has begun her first term this past year.

I wish I could say the same for all Boston residents, however. One of the big stories of Wu’s first year in office were the seemingly constant, aggressively loud and angry anti-mask/anti-vaccine protests that took place outside of her Roslindale home. While I can’t say I have much understanding of or patience for anti-maskers or anti-vaxxers (two communities who together have unquestionably and frustratingly prolonged and worsened this pandemic), of course I support their fundamental, profoundly American rights to hold their own opinions and express their own points of view. I also believe that protest is not only a vital part of our American political and social life (and always has been), but in my book Of Thee I Sing I define it as one of the most consistent forms of both active and critical patriotism across our histories. But the protests outside of Wu’s house were expressly designed to intimidate her into giving in to their demands, and in so doing (indeed, as the main way of so doing) to bother her young children, her neighbors, the whole community with their purposefully excessive noise and disturbance. I’m not suggesting they shouldn’t be allowed to do so (until and unless they break any laws), but I find these protests a reflection of the worst of America in 2022 nonetheless.

Fortunately, Wu hasn’t let that small group of aggrieved assholes derail her goals and plans for Boston, and indeed she’s had an inordinately active and successful first year in office. In keeping with what got my son connected to her in the first place, much of that has been linked to environmental and climate change activism, from the launch of an overarching Green New Deal for the Boston Public Schools to groundbreaking specific proposals like eliminating the use of all fossil fuels in new construction projects for the city. But maybe my favorite Mayor Wu effort to date has been the successful piloting of free public transit in the city—the most prominent story about the MBTA this year has been a continuation of the longstanding clusterfuck (pardon my French, but it’s the only word that works here) that is the T; but Wu is looking not only to change that narrative, but to reframe our entire conversation around public transportation, a conversation that will be absolutely crucial if cities are going to help fight climate change as we move forward. I couldn’t be prouder that my son is so connected to this innovative and inspiring Asian American leader.

September Recap and a new Guest Post this weekend,

Ben

PS. What do you think? Other Asian American lives or stories you’d highlight?

September 29, 2022

September 29, 2022: Asian American Leaders: Lisa Wong

[On September 28th, 2002 the great Patsy Mink passed away. So this week I’ll AmericanStudy Mink and four other Asian American leaders, past and present!]

On a telling story that reveals a lot more than just a leader’s initiative.

One of the cooler things that happened during my first few years as a faculty member at Fitchburg State University was the 2007 election of Lisa Wong as Mayor of Fitchburg. Only 28 at the time of her election (two years younger than me!), Wong was both the youngest woman and the first Asian American woman to be elected mayor anywhere in Massachusetts. A number of my FSU colleagues had worked on Wong’s campaign and/or been early supporters of it and her, which certainly made it feel that the election results were as much as about the campus community and future as they were those of the larger city—and indeed, some of Wong’s many achievements as mayor involved helping bridge the town-gown gap in ways that have continued to echo in the years since the last of her four mayoral terms ended in 2016. She also began the fraught and ongoing but crucial process of revitalizing the city’s downtown and cultural sectors, among other signature goals and achievements of her 8 years as Fitchburg Mayor.

I could write plenty more about what Wong did as mayor (and what she has done since), but the story on which I want to focus for the rest of this post concerns how she became mayor in the first place. In 2007 she was running against three-term incumbent Dan Mylott, a popular figure in the city from well before his time as mayor. As Wong tells it, those in the know told her that of the city’s just over 40,000 residents, about 5000 consistently voted in mayoral elections; Mylott was particularly, overwhelmingly popular with that community of voters, and Wong was advised that she would have to find a way to win over more than half of them if she were to win the election. But Wong’s response was: what about the other 35,000 residents? She focused much of her campaign on finding ways to reach out to and connect with those other Fitchburg residents, including going door to door to meet and talk with folks and families, and convinced enough of them to vote and vote for her specifically that she won the election quite easily (as I understand it).

That’s quite a story, and reveals a lot about Wong’s innovative and forward-thinking perspective and politics (which I’m sure have likewise served her well in those subsequent town manager gigs). But I think it also and even more importantly reveals another side to a topic I’ve written about quite frequently (perhaps more frequently than any other), in this space and manymany others: how we define who is fully, centrally a member of our collective communities, who is American. Voting isn’t the only way we develop such definitions, of course, but it is certainly a consistent and clear one—and, even more than voting itself, the question of who we see as voters and potential voters, on whom our political and social efforts focus, defines so much of politics, policy, and public conversations. As an Asian American, part of one of the communities that for centuries have been far too often ignored in those frames by our white supremacist power structure, Wong was in a particularly good position to help reframe those narratives toward a more inclusive vision—and she did so, for her first election and throughout her time as a Fitchburg and Massachusetts leader.

Last leader tomorrow,

Ben

PS. What do you think? Other Asian American lives or stories you’d highlight?

September 28, 2022

September 28, 2022: Asian American Leaders: Patsy Mink

[On September 28th, 2002 the great Patsy Mink passed away. So this week I’ll AmericanStudy Mink and four other Asian American leaders, past and present!]

On three signature achievements across Mink’s truly groundbreaking career in Congress and government (which included seeking the Democratic nomination for President in 1972!):

1) Educational Progress: After her historic election to Congress in 1964, it would have been understandable if Mink took a while to get her bearings; but instead she immediately began work on vital new legislation that truly reshaped federal education policy. That included two laws introduced in 1965 (her first year in office): the Early Childhood Education Act, which Mink herself introduced to Congress and became the first federal legislation to cover that crucial pre-school period; and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, on which Mink was an important co-sponsor and which made sure that educational progress would be included in the broader Great Society reforms and policies. Indeed, those laws represent some of the most enduring legacies of the Great Society programs, and bear the strong imprint of this first-time, first-year Congresswoman.

2) Title IX: They’re probably not the most enduring and influential law that Mink co-authored, however. That title would have to go to the Title IX Amendment of the Higher Education Act, the 1972 bill which prohibited sex-based discrimination in any federally funded education program and thus guaranteed equal protection and support for women’s athletics (among other areas, but with athletics a particular point of emphasis). As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of this hugely important law, one that in 2002 was officially renamed the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act, we’ve been able to truly chart just how consistently and how much it has helped girls and women participate in and achieve (both in and beyond the world of sports). It’s one of the single most influential federal achievements of the last half-century, and it literally and figuratively has Mink’s name all over it.

3) Environmental Stewardship: Education and women’s rights were thus two foundational and consistent issues on which Mink focused in her 24 total years in Congress (split between 1965-77 and 1990-2002). But as a representative from Hawai’i, Mink was also acutely aware of environmental issues related to the world’s oceans; and after leaving Congress for the first time in 1977, she had the chance to work directly on such issues as Jimmy Carter’s Assistant Secretary of State for Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs (a newly created role that Mink was the first to hold). While she only held that position for a brief time, she thus helped inaugurate a federal, Cabinet-level emphasis on not only those specific issues, but also a broader sense of the multiple layers to environmental conversation, stewardship, and activism. As with all of these achievements, the best way to honor Mink’s passing and her life alike will be to carry on those fights.

Next leader tomorrow,

Ben

PS. What do you think? Other Asian American lives or stories you’d highlight?

September 27, 2022

September 27, 2022: Asian American Leaders: Yuri Kochiyama

[On September 28th, 2002 the great Patsy Mink passed away. So this week I’ll AmericanStudy Mink and four other Asian American leaders, past and present!]

On a few of the many reasons why we should better remember the influential activist and leader.

I’ve written multiple times previously in this space about Yuri Kochiyama, and wanted to keep this first paragraph short so you can check those posts out if you would.

Welcome back! Since I wrote those posts I researched Kochiyama more deeply in order to include her in the Japanese Internment chapter of We the People, and would now argue that she and her activism and leadership can help us better remember at least two important sides to the internment era. For one thing, she exemplifies multiple complex realities of the internment camps: not just their unconstitutional and horrific imprisonment of hundreds of thousands of Americans (a majority of them American citizens like the California-born Kochiyama), but also the stories of Japanese American soldiers who volunteered to serve while interned with their families (a roster that includes both Kochiyama’s twin brother Peter and her future husband Bill) and the complementary activism that took place within the camps. Kochiyama, for example, built on her college English degree to edit a newspaper at her Jerome, Arkansas camp, and within that newspaper published letters from and testimonials about Japanese American soldiers for her “Nisei in Khaki” column. Every interned individual deserves a place in our collective memories, but Kochiyama in particular illustrates those multi-layered histories quite strikingly.

Her lifelong activism after the war, about which I did write more fully in those prior posts (and which was often undertaken in partnership Bill, particularly their shared advocacy for collective memory of and reparations for internment), likewise helps us better remember the lives and legacies of interned Japanese Americans. But Kochiyama’s activism extended far beyond Japanese American causes, and included extensive experience with the Civil Rights Movement (including a friendship with Malcolm X that culminated in her presence in a famous photograph [CW for graphic imagery] of the aftermath of his assassination) and her participation in the October 1977 takeover of the Statue of Liberty by Puerto Rican nationalists. Better remembering that lifelong activism thus helps us engage both with the interconnected nature of many 20th century social movements and with the complex but crucial concept of intersectionality, of how different identities and communities can pull together toward the common causes of equality and social justice. That’s a lesson we sorely still need.

Next leader tomorrow,

Ben

PS. What do you think? Other Asian American lives or stories you’d highlight?

September 26, 2022

September 26, 2022: Asian American Leaders: Pablo Manlapit

[On September 28th, 2002 the great Patsy Mink passed away. So this week I’ll AmericanStudy Mink and four other Asian American leaders, past and present!]

First, a couple paragraphs on the Filipino American labor leader from my book We the People:

“The concentration of many of these early-twentieth-century Filipino arrivals in western U.S. communities of migrant labor led to new forms of inspiring communal organization and activism, ones that also produced corresponding new forms of exclusionary prejudice. The story of Pablo Manlapit and the first Filipino Labor Union (FLU) is particularly striking on both those levels. Manlapit was eighteen when he immigrated from the Philippines to Hawaii in 1909, one of the nearly 120,000 Filipinos to arrive in Hawaii between 1900 and 1931; he worked for a few years on the Hamakua Mill Company’s sugarcane plantations, experiencing first-hand some of the discriminations and brutalities of that labor world. In 1912, he married a Hawaiian woman, Annie Kasby, and as they began a family he left the plantation world and began studying the law. By 1919, Manlapit had become a practicing labor lawyer, and he used his knowledge and connections to found the Filipino Labor Union on August 31, 1919; he was also elected the organization’s first president. The FLU would organize major strikes on Hawaiian plantations in both 1920 and 1924, as well as complementary campaigns such as the 1922 Filipino Higher Wage Movement; these efforts did lead to wage increases and other positive effects, but the 1924 strike also culminated in the infamous September 9 Hanapepe Massacre, when police attacked strikers, killing nine and wounding many more.

Manlapit was one of sixty Filipino activists arrested after the massacre; as a condition of his parole he was deported to California in an effort to cripple Hawaiian labor organizing, but Manlapit continued his efforts in California, and in 1932 returned to Hawaii and renewed his activism there, hoping to involve Japanese, indigenous, and other local labor communities alongside Filipino laborers. In 1935, Manlapit was permanently deported from Hawaii to the Philippines, ending his labor movement career and tragically separating him from his family, but his influence and legacy lived on, both in Hawaii and in California. In Hawaii, the Filipino American activist Antonio Fagelorganized a new, similarly cross-ethnic union, the Vibora Luviminda; the group struck successfully for higher wages in 1937, and would become the inspiration for an even more sizeable and enduring 1940s Hawaiian labor union begun by Chinese American longshoreman Harry Kamoku and others. In California, a group of Filipino American labor leaders would, in 1933 in the Salinas Valley, create a second Filipino Labor Union(also known as the FLU), immediately organizing a lettuce pickers’ strike that received national media attention and significantly expanded the Depression-era conversation over Filipino and migrant laborers. In 1940, the American Federation of Labor chartered the Filipino-led Federal Agricultural Laborers Union, cementing these decades of activism into a formal and enduring labor organization.”

Just a quick addendum: there are many, many reasons to better remember Asian American figures and histories like Manlapit and the FLU. But high on the list is the way in which those stories and histories complicate, challenge, and change our broader narratives of topics like work, organized labor, and protest and social movements in America. Every one of those themes has been as diverse and multi-cultural as America itself, throughout our history just as much as in the present moment; and every one has included Asian Americans in all sorts of compelling and crucial ways.

Next leader tomorrow,

Ben

PS. What do you think? Other Asian American lives or stories you’d highlight?

September 24, 2022

September 24-25, 2022: Faulkner at 125: Digital Yoknapatawpha

[September 25th marks William Faulkner’s 125th birthday. So this week I’ve AmericanStudied Faulkner and other Southern storytellers, leading up to this special weekend tribute to a great new Faulkner website!]

I’ve already highlighted my Dad Stephen Railton’s newest web project, Digital Yoknapatawpha (which features many many collaborators and contributors, but was Dad’s idea so I’m gonna do my filial duty and call it his) in two prior posts:

--This one on all three of his scholarly websites;

--and this one focused on DY and my hopes for how it can be found and used by educators, students, and all interested readers.

Hopefully those posts make clear how unique and impressive this project is, and make all interested FaulknerStudiers (and all the rest of y’all too) ready to check it out for themselves. I could spend many more posts than this one highlighting all the very helpful and very cool specific elements to DY, so here’s just one: the temporal heatmaps that can help readers trace different places across both time and Faulkner’s texts. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a digital humanities tool that truly embodies both words in that phrase—using digital resources to capture a key element to the literary works being studied, and reveal new ways to read and understand them. Just the tip of the DY iceberg!

Next series starts Monday,

Ben

PS. What do you think? Faulkner resources or other Southern storytellers you’d share?

Benjamin A. Railton's Blog

- Benjamin A. Railton's profile

- 2 followers