Benjamin A. Railton's Blog, page 87

January 9, 2023

January 9, 2023: Five Years of Considering History: The First Few Columns

[Five years ago this week, my first Saturday Evening Post Considering History column dropped. That space and work have become crucial components of my career over these years, so for this anniversary I wanted to reflect on a few particular, telling columns from my first year there. Leading up to a special weekend tribute and request!]

When I was initially recruited (by the wonderful editor Jen Bortelabout whom I’ll write in the weekend post) to write a new column for the Saturday Evening Post online, I’m pretty sure we talked directly about the idea for a first columninspired by my Chinese Exclusion Act book. It made sense to start with something familiar, but I knew I wanted soon and consistently to expand into topics about which I hadn’t had as much of a chance to write (or even in some ways think) previously, and I was able to do so immediately with my second column on Rosa Parks and the women behind the Montgomery bus boycott (with a major hat-tip to Danielle McGuire’s book, which I insisted be mentioned as well as cited in the column). That goal meant that one of the main elements of this column would be finding those topics for each post, and the third and fourth reflected two such inspirations: the third on the occasion of Black History Month; and the fourth starting with a historical anniversary (the 50th of Walter Cronkite on the Vietnam War). That balance—of more and less familiar topics, and of different forms of inspiration—has very much continued for the five years since.

Next anniversary reflection tomorrow,

Ben

PS. Thoughts on these columns? Your own writing to share?

January 7, 2023

January 7-8, 2023: Einav Rabinovitch-Fox’s Guest Post on Senatorial Fashion

[Dr. Einav Rabinovitch-Fox is a public historian, writer, and curator who also teaches in the Department of History at Case Western University in Cleveland. Her first book, Dressed for Freedom: The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism, was published by the University of Illinois Press in 2021. Check out this excellent Drafting the Past podcast episode featuring Dr. Rabinovitch-Fox for a lot more of her voice, perspective, and ideas!]

In April 2022, when the Senate voted to confirm the nomination of Ketanji Brown-Jackson to the Supreme Court, a few Republican senators were conspicuously missing from the floor. Among them was Lindsey Graham (R-SC), once a supporter of Brown-Jackson, who announced he would vote against her. Although no drama was expected during roll-call vote, as the Justice was able to secure the required majority for her confirmation, the process was delayed until eventually Graham and three other Republicans casted their “no” votes from the cloakroom.

While no doubt Graham’s absence from the floor was supposed to show his opposition, the reason he was bound to the cloakroom was more mundane: Graham didn’t wear a tie.

The Senate rules, of which Graham is well aware, mandate formal attire on the floor, and thus it was not a coincidence that Graham chose to appear that day with a polo shirt and a blazer. However, his defiant appearance was not so much a protest against sartorial customs, or a sign of a growing style trend among senators, but more of a safe excuse to fend off the backlash to his behavior. Instead of proudly voicing his opposition, Graham used the rigid Senate’s dress as a protection, literally hiding in the closet.

Graham is certainly not a fashion rebel, but in a place like the Senate, which was never a fashion-forward place, not wearing a tie is in fact a political statement. As one of the oldest institutions in our country, the Senate is guided by tradition, especially when it comes to clothing and appearance. And while some updates have been made throughout the years, especially with regards to the appearance of women, the spirit of these rules didn’t change much. Formal wear is still the default when it comes to the senators’ sartorial choices.

Indeed, the Senate is no different from other realms of business, where corporate attire in the form of a dark suit and a tie has been the default for about 100 years. The suit wields power and tradition. It is masculine and authoritative, and thus fits naturally to a place like the Senate. Unlike women who had to carve their way into masculine spaces and used their attire as a way to achieve legitimacy and equality, men’s presence in politics, and by extension, their appearance, was never questioned. In a sense, men don’t need to be fashion rebels because the power of clothes is already granted to them. In fact, the suit is so much associated with masculinity, that any attempts to offer alternative takes on it often happen when women try to claim it as their own. The suit can be a radical statement, but only if a woman wears it.

Wearing a suit and tie—especially if you are a man—is maybe unremarkable, yet adherence to conservative forms of dress doesn’t mean that fashion is marginal to politics. While it is often the appearance of women politicians that get the most scrutiny, in the last couple of years the fashion of men in politics has also received attention. As younger and more diverse candidates began running for office, men, as well as women, have increasingly acknowledged the power of clothes to convey power messages and build their image as politicians. If for years a suit was the way to go, that has started to change as politicians push against those definitions, either as a form of protest like Graham or as a form of image building.

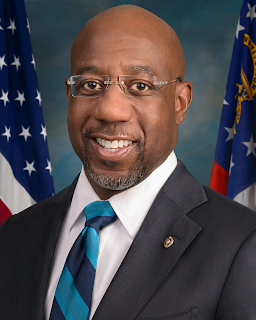

Perhaps the most notable change in the last few election cycles is the move towards casual clothing. For the new cohort of men senators, from Jon Ossoff (D-GA) to Mark Kelly (D-AZ), a tie is a rare sight. Kellyis much more at ease wearing a shirt under a sport or bomber jacket, alluding to his experience as a Navy captain and an astronaut. Ossoff usually wears more formal attire, yet he too is rarely seen with a tailored jacket or a tie. Even Rafael Warnock (D-GA)—maybe the best dresser on Capitol Hill—who is famous for his well-tailored sleek suits, was seen on the campaign trail wearing jeans, sporty vests with tieless shirts, and even t-shirts.

[Official Portrait of Senator Rafael Warnock(D-GA). U.S Senate Photographic Studio, Rebecca Hammel]

This trend of course is not limited to the Senate. The rise of millennials and Gen-Z, as well as the tech industry that espouses more casual look as a symbol of innovativeness and rebellion, all brought with them changes to the office dress code. Moreover, the pandemic and the shift to working from home contributed to the rise in popularity of casual wear, even in conservative strongholds like Wall Street. “Casual Fridays” have now become everyday occurrence, as companies want to broadcast a young, entrepreneurial, and fresh image. In today’s changing markets, a suit doesn’t convey flexibility, but a t-shirt does.

A t-shirt so it seems can also convey power and determination. Not only American politicians are adopting casual wear. The olive-green military t-shirt and pants have been crucial to building Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelensky’s image as a fierce leader. Whether it is in front of Congress or the UN, Zelensky’s new “uniforms” provides a new fashionable language in politics that challenges the traditional power that the formal suit entails.

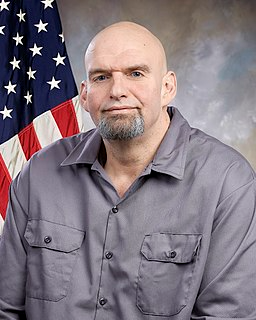

Casualness is indeed the newest trend in politics, and no one understands this better than the newly elect senator John Fetterman from PA. Fetterman, as he himself claims, is not your typical politician and his appearance certainly conveys it: he is a 6’8” with bald head and a biker goatee, lots of tattoos, and usually wears hoodies and shorts. This appearance expresses his authenticity as a candidate and his relationship with voters. He is direct and connects with the “simple man” much better than other politicians who broadcast a more elitist image. Although he comes from a relatively privileged background, has extensive political experience, and like many other politicians is also a Harvard graduate, Fetterman’s appearance relays the image of an “outsider” to politics that voters find appealing.

Fetterman’s height and body size certainly makes it easier to amplify his public presence, but his insistence on wearing sweatshirts and shorts, rather than the conventional suits, is what really makes him stand out. The casualness of the clothes translates to the ease and comfort he feels with people and how he communicates his political message. This style makes him approachable, human, and most of all, relatable – qualities every politician desires.

[Official Portrait of Lt. Governor John Fetterman, Governor Tom Wolf website]

Fetterman’s image is actually enhanced by his visible awkwardness and discomfort every time he is required to wear a suit and a tie. Even when he opts to a more formal wear, his preference is not for a dress shirt or sporty blazers, but work shirts and Dickies trousers, again appealing to a more working-class esthetics that makes his political message attractive. Whereas other politicians, most notably Trump, also tried to capitalize on working-class styles by wearing trucker hats and ill-fitted suits, Fetterman made informality and casualness his trademark and part of his authentic self. In fashion, as well as in politics, it is difficult not to pass as a fake, but Fetterman brings with his style a sense of authenticity that is rare in both realms.

Fetterman’s casual style function differently from those working in high-tech or other creative industries. Casualness in politics is more than just building an image. In an institution that is based on rules and regulations, legal jargon and pro forma, the suit is a symbol and a marker of power. Abandoning the style then is an antithesis, if not a full-blown rebellion. Casualness means disorder, but maybe more importantly, it means democracy. And that is perhaps the whole point. Fetterman does not seek to adjust the suit, or to update the look by ditching the tie, he asks to abandon the suit, and its politics, all together. When Fetterman wears a hoodie sweatshirt he doesn’t convey the innovative spirit of a startup entrepreneur, but a political commitment to social organizing and working-class values.

To be sure, Fetterman can pull off this style in part because he is a big white guy. Yes, his appearance is unconventional for a politician, but him wearing a hoodie will not endanger him or criminalize his presence, as it did in the case of Trayvon Martin. Fetterman’s gender, as well as his size, also work in his favor. While his agenda is not that far from the more progressive wing of the Democratic Party, his unconventional attire doesn’t register him as a radical. He is taken seriously and endearingly because his gender and race protect him.

Fetterman’s political success might bring a new spirit to the Senate. While not everyone is poised to adopt his clothing, his campaigning style is certainly getting some attention in the Democratic Party. In terms of fashion, we might see the young senator’s influence in pushing reforms and changes to the dress code, building on the current trend towards casualness. No doubt, he will have some bipartisan support to loosen things up (at least in terms of ties). More than anything, Fetterman’s fashion style brings with it a new approach to politics and how it can be done. As we expand the range of “what a politician looks like” we also expand the range of what is possible.

However, if the history of the fashion battles in the Senate are any indication, change, whether to the dress code or to the way we conduct politics, will arrive slowly. In fact, at least for now, it doesn’t look like Fetterman is interested in challenging tradition. On his first official day, even though he did not had business on the floor (the only place where rules of decorum apply), he appeared in his one and only ill-fitted, off-the-rack suit, which he also wore for his debate. We might see bolder fashion statements from Fetterman in the future, but so far it looks like he seeks to blend in, not to lead a fashion revolution.

Fashion both wields and yields power, and as such, it is difficult to give up a symbol so powerful as the suit. Fetterman might learn to get at ease with suits and the power they command. But fashion also relies on change, and as such, it also contains opportunities. Fetterman’s style can be such an opportunity. He shows us that power can be gained not only through conventional routes but by constructing alternative images. His appearance asks us to consider our assumptions on who can participate in politics and how, and whose voice and appearance matter.

While fashion is maybe not the most important thing on politicians’ agendas, it is still a tool through which political statements are conveyed and utilized. Fashion allows to reclaim and adjust old conventions, as well as to rebel against them and invent new ones. It might take a while until hoodies will be a common sight on the Hill, but we should not dismiss the power of clothes to shape politics and to make (or break) politicians.

[Next series starts Monday,

Ben

PS. What do you think?]

January 7, 2023: 2023 Predictions

[As I’ve done for the last few years, I wanted to start the New Year by looking back on some prior years that we can commemorate as anniversaries. Leading up to this weekend post with some 2023 predictions!]

While I know full well just how fraught things—if not indeed everything—are right now, I refuse to give in to doomblogging (a close cousin of doomscrolling, natch). So here are three things I’m looking forward to in the New Year:

1) Vegetarianism: I wrote in last year’s Thanksgiving series about the vital lessons I’ve learned from cooking Purple Carrot meals over the last few years, and none of those lessons has been more striking than the significant recent (and still evolving) improvements in meat substitutes and alternatives. Indeed, at a family Thanksgiving dinner my sons and I had a truly delicious faux-turkey loaf that was as tasty as any turkey I’ve ever eaten, and I’d say the same about the Impossible Burgers I’ve tried in recent years. As I wrote in that prior post, I would never proselytize folks about anything food-related; my own personal journey shows how individual and intimate these kinds of choices always are, and we’ve all got to figure out what works for us. But I’m so excited that there continue to be more and better options for enjoying (yes, truly enjoying) a vegetarian diet, and hope that can give more and more folks the chance to take at least a version of that step this year.

2) Climate Activism: As I’ll talk about in next week’s series, this month marks five years of writing my Saturday Evening Post Considering History columnand one of my favorite columns over that time has been this one on the need for critical optimism as we confront the climate crisis. I wrote that in August 2021, and it’s fair to say that the crisis has only deepened over the 18 months since. The “critical” part of critical optimism requires that we recognize that reality as honestly and fully as we can, but I continue to believe that it’s as practically necessary as it is philosophically healthy not to give in to a feeling of hopelessness about where we are or where we’re headed. And I’ve got plenty of folks I can be inspired by in my own continued arc, from the phenomenal new Boston Mayor Michelle Wu to (as I highlighted in that post) the young man who campaigned for her and is moving further into his own work on sustainability and a green future.

3) Public Scholarship: As I draft this post in early December, the future and fate of Twitter, my favorite online community for finding and sharing public scholarship, remains frustratingly up in the air. I hope I’ll continue to have the chance to share such #ScholarSunday threads there, but if not I’ve created a substack for that purpose. And no matter where it happens and where we’re able to find and share it, I remain, as I wrote in last year’s predictions post, so honored to be part of this amazing, growing, vital community of online public scholarly writers and voices.

That Saturday Evening Post series starts Monday,

Ben

PS. What do you think?

January 6, 2023

January 6, 2023: 2023 Anniversaries: 1973 in Music

[As I’ve done for the last few years, I wanted to start the New Year by looking back on some prior years that we can commemorate as anniversaries. Leading up to a weekend post with some 2023 predictions!]

On how a handful of groundbreaking albums tell the story of a year.

1) Pink Floyd, Dark Side of the Moon (March): Pink Floyd had been around for almost a decade by 1973, a legacy of the psychedelic late 60s that was still going very strong into the 1970s. The separation between decades is as arbitrary in music as it is in every other way, after all, and this stunning album reminds us that the 1960s were far from over in 1973.

2) Led Zeppelin, Houses of the Holy (March): But at the same time, new decades, like new years, do bring musical evolution, especially with the rise of new artists; and one of the rock bands that was really taking the mantle of the greats in the early 1970s was Led Zeppelin. Having released four self-titled albums between 1969 and 1971 (you read that right—artists were just insanely prolific in this era), Zeppelin took another step in their continued domination with their fifth album in 1973.

3) Marvin Gaye, Let’s Get It On (August): Rock and roll was still a dominant cultural force in the late 60s and early 70s to be sure, but I would argue that Motown had become the single most influential element in American pop music over those years (and indeed well before, but only building into this moment). No single artist better reflected that dominance than Marvin Gaye, who released a dozen solo albums (along with a handful of collaborations) in the dozen years between 1961 and 1973. Gaye’s 1973 album wasn’t better than all those amazing ones—just another landmark in that stunningly successful career.

4) Stevie Wonder, Innervisions (August): Stevie Wonder wasn’t exactly new in 1973—his debut album The Jazz Soul of Little Stevie dropped in 1962 when he was just 12, and he released fourteen more albums over the next decade (again, insanely prolific)—but I would say he was beginning to evolve from a child novelty act into a full-fledged musical genius in this early 70s moment. The culmination of that evolution was definitely his 1976 masterpiece Songs in the Key of Life, but I’d say that 1973’s Innervisions was a significant step along the way, and helped announce that this next great soul singer had fully arrived.

5) Bruce Springsteen, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. (January) and The Wild, the Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle(November): You knew I couldn’t write about 1973 albums without highlighting the pair of debut albums from my boy Bruce. I’m not going to suggest that either of these albums is as good as the other four I’ve written about here, although I think Wild is pretty darn good (period, and doubly so for an artist’s second album). But I am saying that, y’know, we saw the future of rock and roll in 1973, and it’s name was Bruce Springsteen.

2023 predictions this weekend,

Ben

PS. What do you think?

January 5, 2023

January 5, 2023: 2023 Anniversaries: 1923 and Hollywood

[As I’ve done for the last few years, I wanted to start the New Year by looking back on some prior years that we can commemorate as anniversaries. Leading up to a weekend post with some 2023 predictions!]

On an obvious (if entirely unintended) symbol for cultural hegemony, and a more truly lasting one.

Few landmarks have changed in meaning more dramatically than has the Hollywood Sign. The mammoth sign was first erected in 1923 and read “Hollywoodland,” as that was the name of the new housing development that the real estate moguls Woodruff and Shoults were building in the Hollywood Hills. They and the sign’s designer Thomas Fisk Goff (an English immigrant, local painter, and the owner of the Crescent Sign Company) intended the sign to stay up for only a couple years, just long enough to secure sufficient buyers for these desirable Los Angeles homes. But the Hollywood film industry became significantly more prominent at precisely this moment, and the sign quickly morphed into a symbol of that cultural phenomenon. For another couple decades it read “Hollywoodland,” but when it began to deteriorate and was slated for demolition in 1949, the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce stepped in to preserve the sign, but without the “land” so it could more accurately represent the community and film industry alike. Thanks to another campaign to restore the letters in 1978, it continues to serve as that symbolic landmark to this day, a reflection of both the larger than life and the genuinely mythic nature of Hollywood.

While the Hollywood(land) Sign might be the clearest symbolic representation of that pop culture presence and force, however, I would argue that another 1923 cultural innovation has been significantly more influential than any overarching images or myths of Hollywood. It was in that year that the talented young illustrator and animator Walter “Walt” Disney(not yet 22 years old at the time, and having just moved to Hollywood from Chicago in July) and his brother Roy (older than Walt by a decade and living in Los Angeles already) first created their Disney Brothers Studio. Originally set up to create a series of six short film adaptations of Alice in Wonderland for groundbreaking animation producer Margaret J. Winkler (which resulted in innovative short films that combined animation with live-action), Disney Brothers would truly begin its ascent into the stratosphere five years later with the creation of the character of Mickey Mouse, who appeared in a couple shorts and then in the megahit Steamboat Willie(1928) that truly launched the character and the Disney brand alike.

Neither the Hollywood Sign nor Disney Brothers Studio were in 1923 even a fraction of what they would become over the next few decades, but Disney was of course far closer, or at least a genuine starting point for the work that the studio would continue to do and amplify (rather than a random advertisement intended to last only a brief time). But that’s not the distinction that I want to focus on in this final paragraph. I know that here in 2023 Disney has become a symbol of all that’s wrong with mega-corporations and cultural monopolies and streaming juggernauts and etc., and I understand all that (even though, as I wrote in my Thanksgiving series last November, I love much of what they stream). But I think it’s pretty damn cool that a pair of brothers, the younger a super-talented artistic prodigy and the older a supportive partner, created an illustration and animation studio out of nothing more than their own will and goals, and a century later it’s become one of the most pervasive cultural forces in human history. Even before Mickey steamed onto the scene, Walt and Roy’s 1923 studio was a profoundly powerful embodiment of what Hollywood and creative and popular culture can be, much more so than a collection of giant letters on a hillside.

Last anniversary tomorrow,

Ben

PS. What do you think?

January 4, 2023

January 4, 2023: 2023 Anniversaries: 1873 Inventions

[As I’ve done for the last few years, I wanted to start the New Year by looking back on some prior years that we can commemorate as anniversaries. Leading up to a weekend post with some 2023 predictions!]

On three influential things created in 1873.

1) Levi’s blue jeans: I wrote at length in that hyperlinked post about the backstories that brought together Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis, the two men listed on the 1873 patent application for cotton denim pants reinforced with copper rivets (known initially as blue jeans and then eventually as Levi’s). I’m not sure any 19th century invention has become more synonymous with core elements of the American myth, nor more a part of each and every one of our lives (he wrote with his laptop resting on his blue jeaned legs).

2) Barbed wire: But of course that was far from the only patent application filed in 1873, nor was it the one that most immediately and potently reshaped the American West. That honor would have to go to barbed wire, which was first exhibited by farmer Henry Rose at the De Kalb (Illinois) County Fair in May 1873 and then patented by another farmer, Joseph Glidden, in October. I’m sure if barbed wire hadn’t been invented something else would have come along to profoundly reshape (literally and figuratively) the landscapes of the West and all of the United States—but it was barbed wire that did so most consistently and controversially. Not nearly as comfortable as blue jeans, but that’s a pretty telling duality to be sure.

3) The Comstock Act: A law isn’t technically an invention, but I would argue that the Comstock Act qualifies in at least two ways: it was almost entirely the creation of one man (Anthony Comstock, director of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice); and to a significant degree it did in fact invent, or at least far more overtly define, a new legal category, obscenity. Of course the obscene had been part of human society since the first caveman drew the first penis on the cave wall; but at least in the United States, the Comstock Act represented the first sustained effort to both define and legislate obscenity (and arrest countless individuals for violating these laws). As divisive and destructive as barbed wire was, I’d argue that Anthony Comstock and the Comstock Act had a far more pervasive and punitive influence on American culture.

Next anniversary tomorrow,

Ben

PS. What do you think?

January 3, 2023

January 3, 2023: 2023 Anniversaries: 1823 and the Monroe Doctrine

[As I’ve done for the last few years, I wanted to start the New Year by looking back on some prior years that we can commemorate as anniversaries. Leading up to a weekend post with some 2023 predictions!]

On the limits and possibilities of President James Monroe’s signature policy.

Although the U.S. in the Early Republic was globalizing in all kinds of ways, it was to its fellow North American and Western Hemisphere countries that the new nation was most fully and complicatedly connected. Many of those links were due to slavery, from the economic dominance of the Triangle Tradeto the political, cultural, and social effects of the Haitian Revolution. The relationship between the United States and Mexico (especially after it gained its own independence from Spain in 1821, right in the middle of James Monroe’s presidency) also loomed large over the era. But along with those actual historical events and their effects on the U.S., I would argue that ideas of our national neighbors played a consistently central role in how the United States developed and contested its own narratives of identity in the Early Republic. The controversial 1854 Ostend Manifesto, which plotted a U.S. purchase or annexation of Cuba as a new slaveholding state, offers one of many early 19th century moments when imagined versions of Caribbean or hemispheric connections directly shaped debates within America’s borders.

No single governmental statement or action better reflects that set of hemispheric ties and influences than the Monroe Doctrine. Co-written by James Monroe and his Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, first articulated in Monroe’s December 1823 State of the Union address, and given the name “Monroe Doctrine” in 1850, the doctrine laid out a perspective of hemispheric independence, arguing both that “the American continents … are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any Eurpean powers” and that any such colonization efforts would be viewed “as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States.” That latter clause embodies the most striking limit of the Doctrine, one directly visible in the Ostend Manifesto among many other moments: an entirely U.S.-centric view of the Western Hemisphere, one in which the histories and fates of other nations are significant precisely in relation to how much they impact our own identity and arc. Besides reducing the colonial histories and independence movements of dozens of other nations to an extension of U.S. foreign policy, this side to the Doctrine would become a longstanding justification for direct U.S. intervention in the affairs of these sovereign nations.

Yet if that kind of U.S.-centric narrative and overreaching hemispheric presence became the Doctrine’s effects in practice too much of the time, those are certainly not the only ways to read the statement and perspective themselves. In its own moment, the Doctrine was viewed positively by many of the prominent Latin American revolutionaries then fighting their own battles for independence from European rule: historian John Crow writes that leaders such as Simon Bolívar (fighting in Peru by 1823), Colombia’s Francisco de Paula Santander, Argentina’s Bernardino Rivadavia, and Mexico’s Guadalupe Victoria all “received Monroe’s words with sincerest gratitude.” What would it mean to connect Monroe’s own history as a Revolutionary War soldier and officer and Founding Father to these fellow hemispheric revolutionary leaders? Can we see this as one more manifestation of creolization, a reflection of interconnections and influences between the Western Hemisphere’s revolutions and revolutionaries? I’ve written elsewhere about my desire to see José Martí as part of (if also certainly separate from) the United States, but it would be just as important to see James Monroe as part of Latin American revolutions—not in a U.S.-centric way, but rather as an expression of the parallels and links between the moves toward independence and sovereignty around the region. The Monroe Doctrine offers one potent way to make that case.

Next anniversary tomorrow,

Ben

PS. What do you think?

January 2, 2023

January 2, 2023: 2023 Anniversaries: 1773 and the Tea Party

[As I’ve done for the last few years, I wanted to start the New Year by looking back on some prior years that we can commemorate as anniversaries. Leading up to a weekend post with some 2023 predictions!]

On a few key 1773 moments along the way to December’s Boston Tea Party.

1) The Tea Act: One of the many (many many) crucial historical issues about which I knew very little for much of my AmericanStudying life was the role of the British East India Company in American colonial and Revolutionary history (to say nothing, as that hyperlinked article notes, of its roles in the whole world during this period). It’s not just that the company dominated trade between so much of the world, but also and even more importantly that the English government was willing to do whatever it could to support that economic institution. One such step was the Parliamentary Tea Act, which passed in April 1773 and went into effect in May; the law granted the East India Company virtually sole rights over the tea trade between England and the American colonies. This was far from the first controversial such law—that would be the Stamp Act of 1765—but it was another key step in the road toward Revolution.

2) Franklin’s Satire: If laws were one form of historical documents that helped precipitate those Revolutionary responses, another of course were the impassioned and activist writings—often anonymous or pseudonymous, but no less potent for it—produced by colonial leaders. In September 1773, four months after the Tea Act went into effect, the London newspaper The Public Advertiser published such a work by none other than Ben Franklin himself. Entitled “Rules by Which a Great Empire May be Reduced to a Small One,” Franklin’s essay was deeply satirical, poking fun at a number of British missteps but certainly dwelling at length on precisely the kinds of economic extremes comprised by laws like the Tea Act. It’s impossible to know whether the anger that led to the Tea Party would have happened without this textual encouragement, but again these different layers undoubtedly worked together at the very least.

3) The Dartmouth: Four total ships left England in November 1773 with the first shipments of East India Company tea affected by the new law; one (the William) was lost at sea and the other three arrived in Boston a few weeks later, with the first to dock being the Dartmouth. As that first hyperlinked article above highlights, the Dartmouthhad originated in Nantucket, reflecting the complex interconnections between American shipping and these English companies and laws. Indeed, as I’ve argued both here and in Of Thee I Sing about Revolutionary War Loyalists, that community were just as much part of America (and thus the new United States) as were the revolutionaries. The Nantucket Quaker Rotch family behind the Dartmouth(and a second of the four ships, the Beaver) offer one small window into those multiple American communities, all of which were present at the Boston Tea Party in December 1773 to be sure.

Next anniversary tomorrow,

Ben

PS. What do you think?

December 31, 2022

December 31, 2022-January 1, 2023: December 2022 Recap

[A Recap of the month that was in AmericanStudying.]

December 5: Constitutional Contexts: The Articles of Confederation: A series for the 235th anniversary of Delaware’s ratification kicks off with what was and wasn’t different in the new nation’s first unifying documents.

December 6: Constitutional Contexts: Anti-Federalists: The series continues with three equally significant ways to frame the Constitution’s opposition.

December 7: Constitutional Contexts: Delaware: On that historic anniversary, three relevant contexts for “The First State.”

December 8: Constitutional Contexts: The Bill of Rights: The history, significance, and limitations of the Constitution’s first evolution, as the series drafts on.

December 9: Constitutional Contexts: The 1790 Naturalization Act: The series concludes with why a more frustrating Framing document has to be remembered alongside the Constitution.

December 10-11: Constitutional Contexts: 2022: A special weekend post on one more frustrating and one more hopeful trend when it comes to the Constitution in 2022.

December 12: Fall Semester Moments: Du Bois and Public Education: My annual semester recaps series kicks off with an inspiring student response from my 19C African American Lit course.

December 13: Fall Semester Moments: J. Cole and Me: The series continues with how lifelong learning also happens at the front of the classroom.

December 14: Fall Semester Moments: Crane, Activism, and the American Dream: Truly, inspiringly multi-layered and multi-vocal class discussions, as the series teaches on.

December 15: Fall Semester Moments: Hughes and the Blues: A student paper from my online class that quite simply blues me away.

December 16: Fall Semester Moments: Adult Ed Challenges: The series concludes with two important kinds of challenging questions from adult ed students that will help push my ideas forward.

December 17-18: Signs of Spring (Semester): A special weekend post on a few Spring 2023 courses to which I’m greatly looking forward.

December 19-25: A Defining Wish: Just one multi-part wish for the AmericanStudies Elves this year, on two things I hope to help us do, and one defining reason why.

December 26: 2022 in Review: Top Gun and Sequels: My annual year-end series kicks off with one problem and one possibility with our cultural moment of ubiquitous sequels.

December 27: 2022 in Review: “Woke” Marvel: The series continues with why complaints about Marvel’s new phase are silly, and why they’re more destructive than that.

December 28: 2022 in Review: Hot Girl Music: On the birthday of one of the most badass women I know, the less and more radical layers to a renaissance in badass women artists.

December 29: 2022 in Review: Baseball and Race: One inspiring and one frustrating side of baseball’s diversity in 2022, as the series reflects on.

December 30: 2022 in Review: The Big Lie: The series and the year conclude with what’s not new about the latest attacks on our elections, and what dangerously is.

New Year’s series starts Monday,

Ben

PS. Topics you’d like to see covered in this space? Guest Posts you’d like to contribute? Lemme know!

December 30, 2022

December 30, 2022: 2022 in Review: The Big Lie

[2022 has been a lot. A lot a lot. So for my annual Year in Review series, I wanted to focus mostly on somewhat lighter, pop culture kinds of topics, with just one much more serious exception. Here’s to a better year to come!]

On what’s not new about the latest attacks on our elections, and what is.

As I traced in this Saturday Evening Post Considering History column, white supremacists and reactionaries in America have long—if not indeed always—sought to suppress the vote and interfere with free and fair elections. Not sure I need to say much more about that—that column is very much the tip of the iceberg (and only focused on violent suppression, which of course has been complemented by so many other forms over the centuries, as well as right freaking now), but I hope it makes clear just how much both the right to vote and the practice of democracy itself have been consistently threatened and targeted throughout American history. An thus, as I wrote in another recent Saturday Evening Post column, how much the activists and communities that have struggled and sacrificed to secure, keep, and practice those rights deserve our collective memory and celebration.

So the fact that both the 2020 election specifically and our electoral process more broadly have been under assault throughout the last two years, and certainly throughout 2022 and the lead-up to the midterm elections, is not in and of itself new nor particularly surprising. But I would argue that there are a few key components of this specific attack, the Big Lie, that are in fact both new and hugely destructive. That starts with the fact that the attack originated with an elected official, and the most prominent and powerful elected official in the country at that. As a direct result, many of those who have continued to propagate this attack are themselves either already elected officials or have been seeking office at the time, with many of them seeking precisely roles that would allow them to influence future elections. And as a corollary to those factors, but I would argue as the most striking and destructive element of all, these attacks have not been nearly as couched in the usual fake narratives (worries about voter fraud, for example), but have been far more overtly and directly dismissive of the very idea or goal of free and fair elections themselves.

So yeah, the Big Lie is both an echo of the worst of American history and some brand new devilry. Fortunately, many of its advocates were defeated in those midterm elections; but of course its most famous advocate has announced that he is once again running for office, seeking to participate in the same system and democracy that he and his allies and supporters have worked so tirelessly to undermine and destroy. Which is to say, as I transition to next week’s New Year’s series, politics and America in 2023 are likely to be just as dominated by the Big Lie as was 2022. La lucha continua, my friends.

December Recap this weekend,

Ben

PS. What do you think? Other parts of 2022 you’d reflect on?

Benjamin A. Railton's Blog

- Benjamin A. Railton's profile

- 2 followers