Benjamin A. Railton's Blog, page 75

May 27, 2023

May 27-28, 2023: Barrett Beatrice Jackson’s Guest Post on Norman Rockwell, Robert Butler, and her Grandfather

[Barrett Beatrice Jackson is apolitical scientist and legal historian, as well as a Fellow at the Behavioral International Economics Development Society (BIED). Herwork brings together academic scholarship, public policy and law, and genealogyand family history, as this wonderful Guest Post illustrates!]

NormanRockwell was always a name thrown around in our family. The essence ofAmericana, though I never knew quite why. After my grandfather died, framedSaturday Evening Post covers started showing up, hung in linear fashion,clearly old and faded, around our house. I always knew my grandfather wassomewhat “quirky” – he is the reason why I now have hundreds of books datedback to the early 19th century on U.S. Presidents found at randomgarage sales he’d find over the years.

The story behind the NormalRockwell’s, however, is a bit more complex and one which inspires ahistoriographic resolution that it is the “outliers” – those that go againstthe contemporary stereotypes and who may not be in the history books or regardedas the greatest thinker of their time but nonetheless are central in shaping ourcollective history. There was, and continues to be, a basic goodness of soulthat deafens the noise of the world. We were taught to “Always Live In View ofEternity” – the family mantra being “ALIVE”. Showing up at the insularMethodist church for a couple hours every week wasn’t enough.

Let me provide some context. Beforedesegregation was no longer thought of as un-Godly, and World War II veteranswere reaching middle age, Glenn Brown practiced as an OBGYN in middle Florida.(I’ve been told that after the war, he resolved to bring as much life into the worldto atone for those he took away in Japan.) He was cultured and worldly, despitehaving grown up in Selma, Alabama, during Jim Crowe. He held himself to ahigher standard—a believer in Kantian-like imperatives that transcend societaldefinitions of right versus wrong. He instilled in us all the conviction thatthere is more to life than the “rat race”, as he put it. Thus, he would riskhis safety (and reputation) to travel deep within the black neighborhoods ofrural Florida swampland to provide them free obstetrical care.

Enter Robert Butler. Also defyingsegregation laws, Butler was a penniless black artist who would try to sell hisworks at the same spot along the same rural highway in Okeechobee, Florida, everyday. Inevitably, he and Dr. Brown would meet and, more surprisingly, becomegood friends over the years. Butler painted what he knew: the everglades, andwas a master of water-colored landscapes in a signature style that exuded aunique ability to “read the land”.

Of course, supporting a family on alove of painting meant a life of barely scraping by. So by the late 1960s, hehad to set out on the road to try to sell his paintings from his car. He latertold the St. Petersburg Times, “I was swimming in this fantastic psychologicalsoup at the time; I came from this poor background and yet this door wasopening wide for me, to this universe that could be explored forever. I wantedto paint as much as I could and never looked back.”

From such different backgrounds, thetwo men shared this passion of finding profound meaning in the everydaymundane. Dr. Brown found inspiration in this man who “never looked back” as hehimself lived in deep-seated guilt over those he killed during WWII and for acountry that still vilified racial parity. What did he fight for? How could heatone? In Butler’s world, my grandfather recognized his naivete in making lifea celebration of colors, a purity of soul unmarred by the realities of war.

Thus Dr. Brown began purchasingButler’s paintings for his office and introduced him to other doctors in thecity. Butler would go on to be a father to nine children, most of whom Dr.Brown delivered. Payment was in the form of a new painting. It was anunconventional arrangement but neither individual cared much for fitting anymolds. In this way, everything that seemed at odds – race, class, education, etal – somehow strengthened their friendship.

My grandfather may have subconsciouslybeen jealous of Butler’s natural joie de vivre but that is exactly why hesurrounded himself, working in an extremely sterile hospital environment, withbright paintings that served as inspirational reminders—windows to theoutside—of there being meaning in his being a doctor in such a sociallybackward and hypocritical area of the country. I’d like to think that Butlerrecognized this universal thirst of the soul and that is why his paintings wereborn out of such purpose and effortlessly bright natural beauty.

By the 1990’s, Robert Butler hadbecome a household name in “wild Florida” and proved to be thatone-in-a-million prodigy who had officially made it. He became a symbol of agroup of black artists called “The Florida Highwaymen,” who saw and painted theworld regardless of societal boundaries. In 2004 he was inducted into the FloridaArtists Hall of Fame. He was sought after by all sorts of collectors, hunters,and outdoor enthusiasts. After his death, our family had to promise hischildren that all the now extremely expensive paintings he had made for mygrandfather would not be sold. So they hang amongst the homes of the childrenand grandchildren.

Now you may bewondering how Norman Rockwell fits into this story. The Rockwell originals werenot just haphazardly found by my grandfather; rather, each one was sought afterand selected based on the dates of publication of each Saturday Evening Post.Not necessarily famous dates in history but ones from family birthdays,marriages, personal milestones. Nostalgia personified. A deeply personal andprivate kind that retains symbolism beyond that amorphous concept of“Americana” and the well-known family at Thanksgiving dinner.

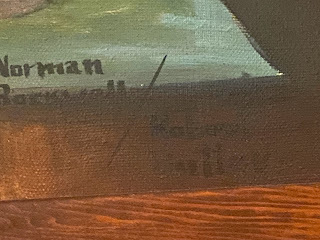

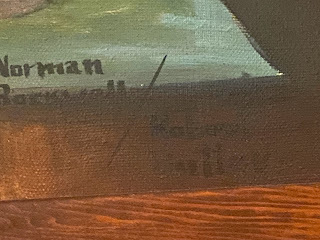

Not unlikeButler’s paintings, they—along with their subjects and dates published—are quintessentialreminders of life’s small miracles amidst the ordinary. And perhaps that multi-layerof interpretation is one factor of Rockwell’s genius. The last painting Butlerpersonalized for my grandfather embodied all of this. One of Dr. Brown’sfavorites of Rockwell’s was his cover depicting a doctor holding anold-fashioned stethoscope to a young girl’s heart. He is kneeling down to herlevel, looking at her in a way that suggests he is mentally picturing all thethings this girl was to grow up to be and do. As a sort of parting gift oncehis career reached new heights, Butler painted this Rockwell work, even copyingthe Rockwell signature, with his own “R. Butler” one to make it unique.

It remained inmy grandfather’s offices throughout the years until he passed it down to mymother, his only child who pursued a career in medicine. As a woman. In theearly 1970s. In Alabama. It then hung in her office until she retired lastyear. Whether she was an assistant professor or chief of staff, the paintingwas always there gaining new meaning as she fought to be taken as seriously asthe male doctors. I do not know exactly how she sees herself in the painting–whether as the timid patient or the all-in devoted physician who encapsulatesan unselfish Hippocratic Oath, despite administrative and politicalencumbrances in today’s current healthcare system. Probably a bit of both.

How then do we narrow in upon what hasbeen, and is, utilitarian in American society? Is it about straining to appealto everyone? Reach the most people for glory rooted in selfishness? Evenstrictly applying J.S. Mill to social movements and the backlash from pandemicsand ensanguine public policies falls short outside of Democratic Theory 101.

On the contrary, it is about honesty:about past decisions and regrets, about recognizing reality is difficult andbeing self-aware and emotionally mature enough not to dwell but to “keeppainting” for the future, so to speak. It is about accepting thatself-forgiveness is a lifelong pursuit.

Allow me to put these rather personalsentiments into a broader context. Sometimes we prefer to romanticize historyalong the lines of “we are fighting in the name of freedom” and do not venturefurther to openly discuss the meaning of “freedom”. The backlash of world warand the new global dichotomy of democratic versus communist superpowersresulted in the 1950’s a decade of re-branding normality, the “traditionalnuclear family”, and selling a new type of American Dream: peace through idealizedstability.

At the same time, just as the HarlemRenaissance signified a growing grassroots resistance to accept that statusquo, others rebelled courageously with their own art, providing a bond thatreached across classes and regions. Able to bring a disillusioned white doctorfrom Selma, AL, to be moved by such sorrowful beauty in the middle of theFlorida Everglades as a reason for hope and purpose to heal such deeplyengrained wounds.

For more on Butler: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Butler_(artist)

Andhis works: https://www.floridahighwaymenpaintings.com/highwaymen/robert-butler/

https://www.invaluable.com/artist/butler-robert-1943-vhquwn7hpz/sold-at-auction-prices/

[MemorialDay series starts Monday,

Ben

PS. Whatdo you think? Guest Posts you’d like to contribute?]

May 27-28, 2023: Barrett Beatrice Jackson���s Guest Post on Norman Rockwell, Robert Butler, and her Grandfather

[Barrett Beatrice Jackson is apolitical scientist and legal historian, as well as a Fellow at the Behavioral International Economics Development Society (BIED). Herwork brings together academic scholarship, public policy and law, and genealogyand family history, as this wonderful Guest Post illustrates!]

NormanRockwell was always a name thrown around in our family. The essence ofAmericana, though I never knew quite why. After my grandfather died, framedSaturday Evening Post covers started showing up, hung in linear fashion,clearly old and faded, around our house. I always knew my grandfather wassomewhat ���quirky��� ��� he is the reason why I now have hundreds of books datedback to the early 19th century on U.S. Presidents found at randomgarage sales he���d find over the years.

The story behind the NormalRockwell���s, however, is a bit more complex and one which inspires ahistoriographic resolution that it is the ���outliers��� ��� those that go againstthe contemporary stereotypes and who may not be in the history books or regardedas the greatest thinker of their time but nonetheless are central in shaping ourcollective history. There was, and continues to be, a basic goodness of soulthat deafens the noise of the world. We were taught to ���Always Live In View ofEternity��� ��� the family mantra being ���ALIVE���. Showing up at the insularMethodist church for a couple hours every week wasn���t enough.

Let me provide some context. Beforedesegregation was no longer thought of as un-Godly, and World War II veteranswere reaching middle age, Glenn Brown practiced as an OBGYN in middle Florida.(I���ve been told that after the war, he resolved to bring as much life into the worldto atone for those he took away in Japan.) He was cultured and worldly, despitehaving grown up in Selma, Alabama, during Jim Crowe. He held himself to ahigher standard���a believer in Kantian-like imperatives that transcend societaldefinitions of right versus wrong. He instilled in us all the conviction thatthere is more to life than the ���rat race���, as he put it. Thus, he would riskhis safety (and reputation) to travel deep within the black neighborhoods ofrural Florida swampland to provide them free obstetrical care.

Enter Robert Butler. Also defyingsegregation laws, Butler was a penniless black artist who would try to sell hisworks at the same spot along the same rural highway in Okeechobee, Florida, everyday. Inevitably, he and Dr. Brown would meet and, more surprisingly, becomegood friends over the years. Butler painted what he knew: the everglades, andwas a master of water-colored landscapes in a signature style that exuded aunique ability to ���read the land���.

Of course, supporting a family on alove of painting meant a life of barely scraping by. So by the late 1960s, hehad to set out on the road to try to sell his paintings from his car. He latertold the St. Petersburg Times, ���I was swimming in this fantastic psychologicalsoup at the time; I came from this poor background and yet this door wasopening wide for me, to this universe that could be explored forever. I wantedto paint as much as I could and never looked back.���

From such different backgrounds, thetwo men shared this passion of finding profound meaning in the everydaymundane. Dr. Brown found inspiration in this man who ���never looked back��� as hehimself lived in deep-seated guilt over those he killed during WWII and for acountry that still vilified racial parity. What did he fight for? How could heatone? In Butler���s world, my grandfather recognized his naivete in making lifea celebration of colors, a purity of soul unmarred by the realities of war.

Thus Dr. Brown began purchasingButler���s paintings for his office and introduced him to other doctors in thecity. Butler would go on to be a father to nine children, most of whom Dr.Brown delivered. Payment was in the form of a new painting. It was anunconventional arrangement but neither individual cared much for fitting anymolds. In this way, everything that seemed at odds ��� race, class, education, etal ��� somehow strengthened their friendship.

My grandfather may have subconsciouslybeen jealous of Butler���s natural joie de vivre but that is exactly why hesurrounded himself, working in an extremely sterile hospital environment, withbright paintings that served as inspirational reminders���windows to theoutside���of there being meaning in his being a doctor in such a sociallybackward and hypocritical area of the country. I���d like to think that Butlerrecognized this universal thirst of the soul and that is why his paintings wereborn out of such purpose and effortlessly bright natural beauty.

By the 1990���s, Robert Butler hadbecome a household name in ���wild Florida��� and proved to be thatone-in-a-million prodigy who had officially made it. He became a symbol of agroup of black artists called ���The Florida Highwaymen,��� who saw and painted theworld regardless of societal boundaries. In 2004 he was inducted into the FloridaArtists Hall of Fame. He was sought after by all sorts of collectors, hunters,and outdoor enthusiasts. After his death, our family had to promise hischildren that all the now extremely expensive paintings he had made for mygrandfather would not be sold. So they hang amongst the homes of the childrenand grandchildren.

Now you may bewondering how Norman Rockwell fits into this story. The Rockwell originals werenot just haphazardly found by my grandfather; rather, each one was sought afterand selected based on the dates of publication of each Saturday Evening Post.Not necessarily famous dates in history but ones from family birthdays,marriages, personal milestones. Nostalgia personified. A deeply personal andprivate kind that retains symbolism beyond that amorphous concept of���Americana��� and the well-known family at Thanksgiving dinner.

Not unlikeButler���s paintings, they���along with their subjects and dates published���are quintessentialreminders of life���s small miracles amidst the ordinary. And perhaps that multi-layerof interpretation is one factor of Rockwell���s genius. The last painting Butlerpersonalized for my grandfather embodied all of this. One of Dr. Brown���sfavorites of Rockwell���s was his cover depicting a doctor holding anold-fashioned stethoscope to a young girl���s heart. He is kneeling down to herlevel, looking at her in a way that suggests he is mentally picturing all thethings this girl was to grow up to be and do. As a sort of parting gift oncehis career reached new heights, Butler painted this Rockwell work, even copyingthe Rockwell signature, with his own ���R. Butler��� one to make it unique.

It remained inmy grandfather���s offices throughout the years until he passed it down to mymother, his only child who pursued a career in medicine. As a woman. In theearly 1970s. In Alabama. It then hung in her office until she retired lastyear. Whether she was an assistant professor or chief of staff, the paintingwas always there gaining new meaning as she fought to be taken as seriously asthe male doctors. I do not know exactly how she sees herself in the painting���whether as the timid patient or the all-in devoted physician who encapsulatesan unselfish Hippocratic Oath, despite administrative and politicalencumbrances in today���s current healthcare system. Probably a bit of both.

How then do we narrow in upon what hasbeen, and is, utilitarian in American society? Is it about straining to appealto everyone? Reach the most people for glory rooted in selfishness? Evenstrictly applying J.S. Mill to social movements and the backlash from pandemicsand ensanguine public policies falls short outside of Democratic Theory 101.

On the contrary, it is about honesty:about past decisions and regrets, about recognizing reality is difficult andbeing self-aware and emotionally mature enough not to dwell but to ���keeppainting��� for the future, so to speak. It is about accepting thatself-forgiveness is a lifelong pursuit.

Allow me to put these rather personalsentiments into a broader context. Sometimes we prefer to romanticize historyalong the lines of ���we are fighting in the name of freedom��� and do not venturefurther to openly discuss the meaning of ���freedom���. The backlash of world warand the new global dichotomy of democratic versus communist superpowersresulted in the 1950���s a decade of re-branding normality, the ���traditionalnuclear family���, and selling a new type of American Dream: peace through idealizedstability.

At the same time, just as the HarlemRenaissance signified a growing grassroots resistance to accept that statusquo, others rebelled courageously with their own art, providing a bond thatreached across classes and regions. Able to bring a disillusioned white doctorfrom Selma, AL, to be moved by such sorrowful beauty in the middle of theFlorida Everglades as a reason for hope and purpose to heal such deeplyengrained wounds.

For more on Butler: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Butler_(artist)

Andhis works: https://www.floridahighwaymenpaintings.com/highwaymen/robert-butler/

https://www.invaluable.com/artist/butler-robert-1943-vhquwn7hpz/sold-at-auction-prices/

[MemorialDay series starts Monday,

Ben

PS. Whatdo you think? Guest Posts you���d like to contribute?]

May 26, 2023

May 26, 2023: Great American Screenplays: Memento

[I hadplanned to feature this week a pre-Memorial Day serieson blockbuster films. But with the ongoing and very necessary WGAstrike, I’ve decided to share instead a handful of older posts which havefocused on films with particularly perfect screenplays. I’d love your thoughtson these as well as your nominees for other great screenplays and writing—in anymedium—for a crowd-sourced weekend post of solidarity!]

[FYI: thispost will focus on some key elements to the final sequence in ChristopherNolan’s film Memento (2000). Which ifyou haven’t seen, go watch and then come on back. I’ll be here.]

On the dark,cynical, and unquestionably human final words of a contemporary Americanclassic.

I might bestretching things a bit by calling Memento (2000) anAmerican classic—after all, it was directed by ; adaptedfrom a shortstory, “Memento Mori,” by his equally English brother Jonathan; andstars Aussie Guy Pearce and Canadian Carrie-Anne Moss in two of the threeprincipal roles. But I’m sticking to my guns, and not just because the film isset in the western United States (specifically Nevada, I believe, based on theglimpses we get of license plates; key earlier events and flashbacks take placein California). To me, some of the film’s central themes, while unquestionablyuniversal in significance, echo particularly American narratives: the idea, orperhaps the myth, of the self-mademan, creating himself anew out of will and ambition, writing his ownfuture on a blank page (or, in this case, his ownbody); theWestern film trope of a lone warrior, a quiet and threatening man withseemingly no identity or past, traveling on a quest for justice and/or revenge,and entering and changing a corrupt town in the process. In those and othercore ways, Memento is deeply andimportantly American.

Given thatAmericanness, and given that it’s a mystery—if ahighly unconventionaland postmodern one to be sure—it’s likely no surprise that Ilove the film. But compared to many of the loves I’ve shared this week, andcompared to my general AmericanStudying attitude for that matter, Memento is also strikingly dark andcynical; it takes that tone throughout, but most especially in its finalrevelations and in theinterior monologue with which it concludes (that scene is more spoilerific thanI’m going to be here, so don’t watch if you haven’t seen the film!). Thatmonologue’s middle section feels logical and rational enough, particularly thelines “I have to believe in a world outside my own mind. I have to believe thatmy actions still have meaning, even if I can’t remember them. I have to believethat when my eyes are closed, the world’s still here.” But it begins with thespeaker, protagonist Leonard Shelby, making one of the most blatantly andpurposefully self-deceptive and disturbing choices ever put on film, whilethinking, ““Do I lie to myself to be happy? … Yes I will.” And so when Leonard(and the film) ends by arguing, “We all need mirrors to remind ourselves who weare. I’m no different,” it seems, in the specific context of what he has doneand is doing, who and what he has been revealed to be, to be a profoundlypessimistic perspective on human nature and identity.

Maybe itis that pessimistic—it’s okay if so, not everything can end on notes of hard-wonhope, much as I enjoy the concept. The world’s more complex andmulti-faceted than that. But if we take a step back from some of the specificsof what Leonard is doing at this moment, it’s also possible to read his actionshere, and throughout the film, as purely and simply and definingly human. He’strying to make meaning out of the world around him, out of the details of hisown life (and most especially the hardest and toughest of them), out of whathas happened and what is happening and what he hopes to make happen in the timeto come. What Leonard does overtly—in those tattoos on his skin, in hisphotographs and note cards and wall hangings, in his constant interiormonologue—is what we all do more subtly but just as constantly: read andrespond to the world around us, and make it part of our developing narrativesand stories and identities. Granted, I hope that we can do it in lessdestructive ways than Leonard; he does have that unique condition tocontend with, after all (spoilers there too!). But we all do it, and one of thethings I love most about Memento isits ability to hold that mirror up to us and how we move through the world.

Crowd-sourcedpost this weekend,

Ben

PS. So onemore time: what do you think? Other great screenwriting you’d nominate?

May 25, 2023

May 25, 2023: Great American Screenplays: The Opposite of Sex and You Can Count on Me

[I hadplanned to feature this week a pre-Memorial Day serieson blockbuster films. But with the ongoing and very necessary WGAstrike, I’ve decided to share instead a handful of older posts which havefocused on films with particularly perfect screenplays. I’d love your thoughtson these as well as your nominees for other great screenplays and writing—in anymedium—for a crowd-sourced weekend post of solidarity!]

Onnontraditional families in groundbreaking children’s books and provocativefilms.

The combination of being aprofessional analyzer of literature and being a daily reader of at least acouple children’s books means that I spend quite a bit of time—some might sayway too much time, but I yam what I yam—analyzing those books. That’sespecially true of the ones that I’ve read enough by this point to be able torecite them largely by heart, freeing my mind for even deeper such analyses.And near the top of that list, both because I have read it a ton and becauseit’s just full of mysteries awaiting—nay, demanding—my analytical attention, isThe Cat in the Hat.The most striking mysteries are the most central ones: why is the Cat sothoroughly destructive a presence in the home of Sally and the unnamednarrator, and what are kids to take away from this tale of an uninvited houseguest who bends rakes, tears gowns, traumatizes fish, and the like? Butunderlying those mysteries is an even more foundational, and (given the book’s 1957publication date) even more striking, one: why has Mother left her twoyoung children alone for the day, and where’s Father?

I might be reading too much intoit (shockingly), but it seems to me that Mother is a single parent, and thatbecause of that status she sometimes has to leave her kids at home alone(leaving them open in the process to the advances of strange men, or male catsat least, and their wild and destructive Things, but again I’m really not surewhat to make of that). If so, that would make Cat a pretty significantly alternative vision of family in the eraof LeaveIt to Beaver and, more relevantly, of the Little Bear books, which feature Mother Bear who stays at homeand sews and cooks and Father Bear who goes off on long fishing trips in hishat and tie. Over the next few decades, of course, our pop culture images offamily would become significantly more diverse and varied, and single parents thusless striking of a prospect (although in many representations, as in the 1980sTV shows Who’s the Boss? and Full House, those single parent familiesare due to deaths, not divorce or children born out of wedlock). But I wouldargue that our most dominant narratives of family identity still rely heavilyon very traditional nuclear models; and relatedly, one role for many out-of-the-mainstreamtexts (such as independent films) has been to push back on those models and constructtheir own alternative visions of family.

Two of the most smart andsuccessful indie films of the last fifteen years, Don Roos’ The Opposite of Sex(1998) and Kenneth Lonergan’s You Can Count On Me(2000), are centered on precisely such alternative family units. Lonergan’s isslightly more conventional, with pitch-perfect Laura Linney’s never-marriedsingle mother trying to balance raising her son, working full-time (andbeginning an affair with Matthew Broderick’s married co-worker), and motheringher wayward brother (played to equal perfection by Mark Ruffalo); but thereason for their close sibling relationship, the death of both of their parentswhen they were very young, makes them a fundamentally distinct kind of family.On the other hand, Roos’s vision of family is purposefully non-traditional andextreme—the film’s central family unit features a teenage runaway (ChristinaRicci), her gay step-brother (Martin Donovan), his young boyfriend who thenbecomes Ricci’s boyfriend (Ivan Sergei), and the sister (Lisa Kudrow) ofDonovan’s former boyfriend who had died of AIDS—but by the end of the filmmakes clear how much these characters, and the few others who have come intotheir circle, have become most definitely a family in the fullest senses,including the presence of two newborn babies in the mix. Similarly, both moviestake very cynical and sarcastic tones toward themes like love and loyalty formuch of their running time, yet by their conclusions they have become (inentirely believable and not at all clichéd ways) testaments to how much theircharacters and relationships emblematize those themes (if at times in spite ofthemselves).

Suchnon-traditional families are, of course, no more necessarily representative asimages of the American family than were Beaver’s and Little Bear’s; it is,instead, very much the spectrum of possibilities for what family is and meansthat represents the variety and diversity of American experiences and models.And thanks to some of our most talented artistic voices, from Dr. Seuss up toRoos and Lonergan, our popular culture includes, and thus helps make morepresent and (ultimately) more fully accepted, many more of those possibilities. Lastgreat screenplay tomorrow,

Ben

PS. Whatdo you think? Other great screenwriting you’d nominate?

May 24, 2023

May 24, 2023: Great American Screenplays: Affliction and A Simple Plan

[I hadplanned to feature this week a pre-Memorial Day serieson blockbuster films. But with the ongoing and very necessary WGAstrike, I’ve decided to share instead a handful of older posts which havefocused on films with particularly perfect screenplays. I’d love your thoughtson these as well as your nominees for other great screenplays and writing—in anymedium—for a crowd-sourced weekend post of solidarity!]

On winter’s and America’s possibiliities and limits in two dark andpowerful films.

When you think about it, snow andthe American Dream have a lot in common. (Don’t worry, I’m not talking aboutrace. Not this time, anyway.) Both are full of possibility, of a sense ofchildlike wonder and innocence, conjuring up nostalgic connections to ourfamilies and our childhoods as well as ideals of play and community and warmth(paradoxical for snow I know but definitely true for me—snow always makes methink of hot chocolate and fires in the fireplace). Yet as we get to be adults,both also suggest much more realistic and limiting and even threateningdetails, of dangerous conditions and losses of power and the cold that can setin if we can’t afford to heat our home. And once we have kids of our own, the coexistence of those twolevels is particularly striking—seeing their own excitement and innocenceand thorough focus on the possibilities, and certainly sharing them, but alsoworrying that much more about whether we can get them through the drifts, drivethem safely where they need to go, keep them warm.

I might be stretching the connection to itsbreaking point, but the link might help explain why so many films that explorethe promises and pitfalls of the American Dream seem to do so amidst asnow-covered landscape. Near the top of that list for me are twocharacter-driven thrillers from the late 1990s: Paul Schrader’s Affliction (1997) and Sam Raimi’s A Simple Plan (1998). Both are basedon novels—the former a work of literary fiction by the late great RussellBanks, the latter a page-turning thriller by ScottSmith—but both, to my mind, are among those rare examples of films thatsignificantly improve upon the source material; partly they do so throughamazing screenplays (Smith interestingly wrote the screenplay based on his ownbook, and I would argue changed it for the better in every way), but mostlythrough inspired and pitch-perfect casting: Afflictioncenters on a career-bestperformance from Nick Nolte, but his work is definitely equaled by JamesCoburn (in an Academy-Award winning turn), Sissy Spacek, Mary Beth Hurt, andWillem Dafoe; while Simple is trulyan ensemble piece, with BillyBob Thornton and Bill Paxton both doing unbelievable work but greatcontributions as well from Bridget Fonda, Brent Briscoe, Chelcie Ross, and GaryCole. And in both, again, the snowy setting—small-town New Hampshire in Affliction, small-town North Dakota in Simple, but they might as well be nextdoor—is a central presence and character in its own right.

The multiple, interconnectingplot threads of both films are complex, rich, and intentionally suspenseful andmysterious, and I’m most definitely not going to spoil them here. But I willsay that both are, at heart, stories of the dreams and weaknesses, the idealsand failures, that we inherit from our parents, and how as adults (andespecially perhaps as adults struggling with the responsibilities of family andparenthood) we try to live up to and beyond the dreams and ideals but arepulled back by and ultimately risk becoming ourselves the weaknesses andfailures. It is perhaps not much of a spoiler either (just look at the titles!)to note that both films, while offering their characters and audiences glimpsesof possibility and hope, bring them and us to extremely bleak final images,worlds where the snow storms may have passed but where the silence andlifelessness they have left behind are all we can see and all we can imagine.And both do so, most powerfully, by bringing their protagonists back to theirchildhood homes, sites (in these cases) at one and the same time of those mostinnocent ideals and of some of the strongest influences in turning those idealsinto something much darker and colder.

When it comes towintry or especially holiday fare, these two definitely aren’t It’s a Wonderful Life, which certainlyconnects its own bleakmiddle section very fully to a world of snow and storm but which of course ends with its protagonist inthe warmest and most hopeful possible place (and in a home that has becomeagain the source of such ideals). But either could make a pretty evocative snowday double feature with that equally great film of the American Dream and itslimits. Nextgreat screenplay tomorrow,

Ben

PS. Whatdo you think? Other great screenwriting you’d nominate?

May 23, 2023

May 23, 2023: Great American Screenplays: Chinatown

[I hadplanned to feature this week a pre-Memorial Day serieson blockbuster films. But with the ongoing and very necessary WGAstrike, I’ve decided to share instead a handful of older posts which havefocused on films with particularly perfect screenplays. I’d love your thoughtson these as well as your nominees for other great screenplays and writing—in anymedium—for a crowd-sourced weekend post of solidarity!]

On aclassic film noir mystery that’s also a pitch-perfect historical fiction.

I don’t think I need to use too muchspace here arguing for the greatness of Chinatown (1974).By any measure, from contemporary awards (ie, nominated for 11 Oscars and 10BAFTAs and 7 Golden Globes) to historical appreciations (named to the NationalFilm Registry by the Film Preservation Board in 1991) to ridiculously obviouscriteria (a 2010 pollof British film critics named it “the best film of all time”!), RomanPolanski’s film noir (although it feels at least as right to write “RobertTowne’s film noir,” since the screenplay is to my mind the greatest one ever filmed and ofcourse Polanski is now a rightly disgraced figure) about a world-weary privatedetective and pretty much everything else in 1937 Los Angeles is one of themost acclaimed and honored American films. It stars Jack Nicholson at theabsolute height of his career and powers; features a pitch-perfect supportingcast including legendary director John Huston as one of the great villains ofall time; centers on a multi-generational Southern California familial andhistorical mystery that would make RossMacDonald proud; is equal parts suspenseful, funny, sexy, dark, and emotionallyaffecting; and has the single greatest final line ever (not gonna spoil it orany main aspect of the plot here). If you haven’t seen it yet, I can’trecommend strongly enough that you do so.

On top of all of that, I think Chinatown is one of the very few hugelysuccessful and popular American films that is deeply invested in complex andsignificant American Studies kinds of questions (interestingly, it lost theBest Picture Oscar to another such film: The Godfather Part II). By the1970s it was likely very difficult to remember—and is of course even moreunfamiliar in our own Hollywood-dominated cultural moment—just how unlikely ofa site Los Angeles had once been for one of the nation’s largest and mostimportant cities; despite its close proximity to the Pacific Ocean, LA is moreor less built in a desert, and by the turn of the 20th century, whenthe city’s population had just moved past the 100,000 mark, it seemedimpossible for the city to provide enough water to support that community. Ittook the efforts of one particularly visionary city planner, WilliamMulholland, to solve that problem; Mulholland and his team designed andconstructed the LosAngeles Aqueduct, a mammoth project that, once completed in1913, assured that the city could continue to support its ever-growing(especially with the rise of Hollywood in the 1920s) population.

But if that’s the basic historicalnarrative of LA’s turning point, an American Studies perspective would want topush a lot further on a number of different factors and components within that:where the water was coming from, and what happened in those more rural and agriculturalcommunities are a result of the aqueduct’s creation; how much of the moneyinvolved was public, how much was private and from whom, and if the projectbenefited the whole of the city equally or if its effects were similarly linkedto class and status; what role LA’s significant diversity—even in those earlyyears it already included sizeable Mexican, African, and Asian Americanpopulations, for example—played in this process; whether the city’s builtenvironment, its architecture and neighborhoods and streets and etc., shiftedwith the new availability of water, or whether there were other factors thatmore strongly influenced its planning; and so on. And perhaps the mostimpressive thing about Chinatown isthat it manages at least to gesture at almost all of those questions andissues, without becoming for even a moment the kind of (forgive me) dryhistorical drama that they might suggest.

Next greatscreenplay tomorrow,

Ben

PS. Whatdo you think? Other great screenwriting you’d nominate?

May 22, 2023

May 22, 2023: Great American Screenplays: Lone Star

[I hadplanned to feature this week a pre-Memorial Day serieson blockbuster films. But with the ongoing and very necessary WGAstrike, I’ve decided to share instead a handful of older posts which havefocused on films with particularly perfect screenplays. I’d love your thoughtson these as well as your nominees for other great screenplays and writing—in anymedium—for a crowd-sourced weekend post of solidarity!]

[FYI:Spoilers for Lone Star (1996) in whatfollows, especially the last paragraph!]

On twoexchanges in my favorite film that capture the complexities of collectivememory.

I believeI’ve writtenmore about my favoritefilmmaker, John Sayles, in this space than anyother singleartist, including an entire October2013 series AmericanStudying different Sayles films. Yet despite thatconsistent presence on the blog, I believe I’ve only focused on my favoriteSayles film, and favorite American film period, LoneStar (1996) forabout half of one post (if oneof my very first on this blog, natch). That’s pretty ironic, as I could easilyspend an entire week’s series (an entire month? All of 2019???) focusing ondifferent individual moments from LoneStar and the many histories and themes to which they connect. I’ll spareyou all that for the moment, though, and focus instead on the film’s mostconsistent theme: the fraughtand contested border between the U.S. and Mexico. Lone Star’s fictional South Texas townis named Frontera (a clear nodto Gloria Anzaldúa), located directly on the border withinfictional Rio county; and as usual when Sayles journeys to a particular placeto create a story and film about that setting, he delves deeply and potentlyinto the histories and contexts that inform that world.

Twospecific dialogue exchanges/scenes focused on the Alamo illustrate a couple ofthe many lenses that Sayles and his film provide on the particular theme ofcollective memories of the battle and the border. Very early in the film we seeone of the film’s principal protagonists, high school history teacher Pilar Cruz (thewonderful, tragicallylost Elizabeth Peña), debating her school’s new, multi-culturalcurriculum with a multi-ethnic, angry group of parents. Pilar is defending hergoal of presenting different perspectives on history, and an enraged Anglofather responds, “I’m sure they’ve got their own version of the Alamo on theother side, but we’re not on the other side!” But Pilar responds calmly that“there’s no reason to get so upset,” noting that their ultimate goal has simplybeen to highlight a key aspect of life for all those kids growing up in a townlike Frontera, past and present: “Cultures coming together, in positive andnegative ways.” For the Anglo father, Frontera and Texas are “American,” bywhich he clearly means Anglo/English-speaking like himself; the Mexicanperspective is “the other side.” But what Pilar knows well, from personalexperience as well as historical knowledge, is that Frontera’s America (and, byextension, all of America) is both Mexican and Anglo American, English- andSpanish-speaking, and thus that multiple versions of the Alamo are part of thisone place and its heritage, legacy, and community.

In thefilm’s final scene (again, SPOILERS in this paragraph, although I won’t spoilall the details as the film is a mystery on multiple levels), Pilarcommunicates a different perspective in conversation with one of the film’sother main protagonists, Chris Cooper’s SheriffSam Deeds. Pilar and Sam are former high school sweethearts pulled apart bycomplex family and cultural dynamics and now just beginning to reconnect, andin this scene are debating whether and how they can truly start once more.Pilar makes the case to a doubting Sam that they can indeed “start fresh,” andin the film’s amazing final lines, argues, “All that other stuff? All thathistory? To hell with it, right? Forget the Alamo.” That might seem like astriking reversal from both her earlier perspective and her job as a historyteacher, and indeed from the film’s overall emphasis on the importance (ifcertainly also the difficulty) of better remembering histories bothpersonal/familial and communal/cultural. But I would argue—and I know Sayleswould too, as I had the chance to talk about this scene with him when I met himbriefly in Philadelphia at an independent film festival—that what Pilar wantsto forget is not the actual past but the mythic one constructed too often incollective memories and symbolizedso succinctly by the phrase “Remember the Alamo.”Forgetting the Alamo, that is, might just help us remember better, a complexand crucial final message fitting for this wonderful film.

Next greatscreenplay tomorrow,

Ben

PS. Whatdo you think? Other great screenwriting you’d nominate?

May 20, 2023

May 20-21, 2023: Our Watergate

[On May 18th,1973, the nationally televised SenateWatergate hearings began. So for the 50th anniversaryof that historic moment, this week I���ve highlighted one telling detail each fora handful of the key figures in those hearings. Leading up to this weekend poston a few contemporary echoes of that moment!]

On three contemporarypolitical and American stories that echo but also frustratingly diverge fromelements of Watergate.

1) AlexanderVindman: In many ways, presidential whistleblower Alexander Vindman is oneplace where our current moment diverges positively from Watergate. While that1970s scandal relied on a combination of anonymous sourceslike ���Deep Throat��� and co-conspirators like John Dean, Vindman is adedicated and inspiring public servant who came forward openly andof his own volition to testify about President Trump���s illegal actions. Indeed,I opened OfThee I Sing by highlighting Vindman as a model of American criticalpatriotism. But at the same time, both he and his twin brother faced significantand frustrating career consequences after Vindman���s courageous actions andtestimony, and that���s a reflection of how much worse the Trump White House wasthan even Nixon���s.

2) The Senate: There are lots of factors in thatfrustratingly worse 21st century administration and moment, but highon the list has to be a deeply craven and even cultist group of Republicanelected officials. That was especially evident in the Senate, the body thatfeatured a number of the 1970sRepublican leaders who recognized and helped stop President Nixon���s lawlessactions. If anything, Trump���s were both more lawless and more blatant, oftenadmitted directly in TV interviews, on Twitter, and beyond. Yet a significantmajority of Republican Senators failedto step up to hold this most lawless and anti-American presidentaccountable (although it���s worth highlighting the sevenwho did vote to impeach, the second time), helping extend and deepen ourworse than Watergate moment.

3) The Media: I didn���t focus on it much in thisweek���s series, but of course there���s no way to tell the story of Watergate���indeed,there is likely no such story at all���without featuring the intrepid WashingtonPost reporters who investigatedand broke that scandal. Moreover, the broader political media were able andwilling to recognize what that scandal meant, and to help frame President Nixonand his administration accurately as lawless and corrupt in ways that continuedto shape public conversations after his resignation (and despite Ford���sfrustrating pardon of Nixon). Given that just two days before I���m draftingthis post CNN hosted a disastrousand damaging ���Town Hall��� with the ex-president whose last public action wasto orchestrate and lead a violent insurrection and attempted coup, I think it���sfair to say that the media has, to this point at least, done a far worse job inits coverage of Trump���s illegal and anti-American actions.

Nextseries starts Monday,

Ben

PS. Whatdo you think?

May 19, 2023

May 19, 2023: Watergate Figures: Jill Wine-Volner

[On May 18th,1973, the nationally televised SenateWatergate hearings began. So for the 50th anniversaryof that historic moment, this week I’ll highlight one telling detail each for ahandful of the key figures in those hearings. Leading up to a weekend post on afew contemporary echoes of that moment!]

One of thesingle most famous moments in the long, multi-stage process that was theWatergate hearings was when Justice Department investigator Jill Wine-Volner cross-examinedPresident Nixon’s secretary (and close personal friend) RoseMary Woods about the infamous 18.5 minute gap on the Watergate recordings. Wine-Volner(who subsequently divorced and remained, and so is now Jill Wine-Banks)recounted that pivotal exchange in detail for this2020 Salon interview, making clear just how much planning, preparation, andstrategizing went into what was without doubt a turning point in the case andscandal. Yet in 1973, Wine-Volner was even more famous for thefrequent miniskirts she wore to work, a professionaland fashion choice that became the subject of agreat deal of consternation and controversy. I almost wrote “surprisinglygreat deal” there, but I’m not sure there’s anything surprising, then or now,about a hugely talented young female attorney being subject to such overtlysuperficial and stereotyping narratives. To make sure we don’t replicate thatproblem, I’d ask you to take away from this post Wine-Volner’s vital cross-examination,a key Watergate moment to be sure.

One of themost

Specialpost this weekend,

Ben

PS. Whatdo you think?

May 18, 2023

May 18, 2023: Watergate Figures: Archibald Cox Jr.

[On May 18th,1973, the nationally televised SenateWatergate hearings began. So for the 50th anniversaryof that historic moment, this week I’ll highlight one telling detail each for ahandful of the key figures in those hearings. Leading up to a weekend post on afew contemporary echoes of that moment!]

While theWatergate hearings absolutely shifted public opinion on the scandal and theNixon administration, it was a parallel event that provided the most directimpetus for the possibility of impeachment (and thus Nixon’s preemptiveresignation). When Watergate SpecialProsecutor Archibald Cox Jr. refused to back down from asubpoena for Nixon’s illegal private recordings, Nixon fired Cox in theOctober 1973 event that became known as theSaturday Night Massacre; it was that unconstitutional firing and the uproarit produced which truly set the impeachment conversations in motion. Given thatparticular context, it’s quite striking and telling that Cox would go to be chairof the board of directors for a dozen years (from 1980 to 1992) of Common Cause, a groundbreaking and vitalbipartisan organization (founded just three years before the Watergate hearingsand still active to this day) advocating for government reform, transparencyand accountability, and a government that, as their mission statement puts it, “servesthe public interest.” In some ways Watergate was and remains singular, but inmany others it was a bellwether of a great deal of issues and debates to come,and Archibald Cox continued to be part of those conversations long after hisspecial prosecuting of Watergate came to a close.

LastWatergate figure tomorrow,

Ben

PS. Whatdo you think?

Benjamin A. Railton's Blog

- Benjamin A. Railton's profile

- 2 followers