Benjamin A. Railton's Blog, page 258

June 5, 2017

June 5, 2017: The Pulitzers at 100: The Good Earth

[The first Pulitzer Prizeswere given out 100 years ago, on June 5, 1917. So to celebrate that centennial, this week I’ll be AmericanStudying five Pulitzer-winning works of fiction, leading up to a special weekend post on the most recent winner!]On the obvious limits of an influential novel, and one way to move beyond them.Between its debut in 1901 and the end of World War II, the Nobel Prize in Literature was only given to three American writers; students of American literature might be able to guess that Sinclair Lewis and Eugene O’Neill were two of those recipients, but I’m willing to bet that you could stump most guessers with the third: Pearl Buck, who received the Nobel in 1938 (just two years after O’Neill). Buck had published a handful of novels by that time, as well as semi-biographical books about her mother and father, but to my mind she received the Nobel for one reason: her hugely popular and influential, Pulitzer-winning novel The Good Earth (1931). Focused on Chinese farmer Wang Lung and his multi-generational family in the years before World War I, Buck’s novel, along with the popular 1937 film adapation of the same name, has been credited with significantly shifting American public opinion toward China, a change that also affected our foreign policy and our role in World War II. The novel was the #1 U.S. bestseller of both 1931 and 1932, has remained in print ever since, and was chosen for Oprah’s Book Club in 2004, to cite a few examples of its continued prominence and influence in the nearly ninety years since its publication.Pearl Sydenstricker (1892-1973), the daughter of missionaries, moved with her parents to China was she only five months old, attended Randolph-Macon Woman’s College in Virginia but then returned to China as a missionary herself, married another missionary John Buck in 1917 and raised two daughters (one adopted) in China, and was living in Nanking at the time she wrote The Good Earth, only moving to the United States for good in 1935. As detailed and analyzed in Jane Hunter’s wonderful book The Gospel of Gentility: American Women Missionaries in Turn-of-the-Century China (1984), missionary identities and communities were complex and multi-layered, with Buck’s (as I’ll return to in a moment) even more so than most. But at the same time, a missionary to China is not only not a native-born Chinese person; he or she is very much not an immigrant either, instead performing a role that by definition remains separate from and outside of that culture. Although Buck was deeply immersed in Chinese culture, I believe that missionary perspective still influenced her work in The Good Earth, and particularly her consistent focus on Wang Lung’s relationships with his wife and multiple concubines. (The film is much more overtly stereotyping, especially in its casting choices.) At the very least, it’s important to recognize that Earth is an American novel about China, not a Chinese novel.With that said, however, it’s also important to note that Buck was far from a typical Christian missionary to a non-Christian nation. On a theological and organizational level, she took the Modernist side in the Presbyterian Church’s Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy of the 1920s and 30s, a perspective that led to Buck’s resignation from her missionary role just a year after Earth’s publication. Moreover, she weeded those views to an evolving, striking perspective on missionaries and culture, as evidenced by her 1932 lecture “Is There a Case for Foreign Missions?” (published in Harper’s in January 1933 ), which controversially answered that question in the negative. Those evolving views, as well as her own experiences as the mother of an adopted Chinese daughter, led Buck to co-found Welcome House, Inc., the first international, interracial adoption agency, in 1949. None of those details make Buck or her novel any more Chinese, as I believe she herself would be the first to admit; but they certainly reflect an individual striving to move away from the religious, cultural, and even national categories in which she had been born and raised, and to embody—in her perspective, in her family, and, it certainly seems, in her writing—a deeply cross-cultural identity instead. The Good Earth might mark one partial and imperfect stage in that evolution, but that nonetheless offers an important additional lens through which to read this compelling novel.Next Pulitzer winner tomorrow,BenPS. What do you think? Thoughts on other prize-winning (or –worthy) books?

Published on June 05, 2017 03:00

June 3, 2017

June 3-4, 2017: May 2017 Recap

[A Recap of the month that was in AmericanStudying.]May 1: DisasterStudying: The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake: A series on the 80thanniversary of the Hindenburg crash kicks off with inspiring communal responses to a destructive disaster.May 2: DisasterStudying: The Triangle Fire: The series continues with three legacies of a horrific early 20th century industrial disaster.May 3: DisasterStudying: Boston’s Great Molasses Flood: Three telling details about a unique North End disaster, as the series rolls on.May 4: DisasterStudying: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927: Connecting America’s most destructive river flood to three prominent historical figures.May 5: DisasterStudying: Representing Katrina: Three stages of artistic depictions of the recent, controversial tragedy.May 6-7: DisasterStudying: The Hindenburg: The series concludes with two contexts for the airship crash, one justifiably famous and one much more complex but worth remembering.May 8: The Scholars Strategy Network and Me: SSN Origins and Goals: An SSN series begins with three contexts for how and why the group was created.May 9: The Scholars Strategy Network and Me: Online Writing: The series continues with SSN and the moment that changed everything in my career.May 10: The Scholars Strategy Network and Me: Online Writing, Extended: Two SSN-inspired posts that extended beyond their online starting points, as the series rolls on.May 11: The Scholars Strategy Network and Me: No Jargon Podcast: What I learned from contributing to SSN’s wonderful podcast, and why we should all listen to it.May 12: The Scholars Strategy Network and Me: Boston March for Science: Three takeaways from my participation in the activist effort.May 13-14: The Scholars Strategy Network and Me: Leadership Summit: The series concludes with three things about SSN that a recent event helped clarify for me.May 15: Spring 2017 Reflections: Fruitvale and Black-ish in Writing II: An end-of-semester series kicks off with the limits and benefits of using contemporary multimedia texts in first-year writing.May 16: Spring 2017 Reflections: Sui Sin Far in the American Novel: The series continues with what didn’t work and what did when I used a short story collection in a novel course.May 17: Spring 2017 Reflections: Contemporary Connections in American Lit I: Two ways I linked my most historical class to our current moment, as the series rolls on.May 18: Spring 2017 Reflections: Contemporary Issues in Adult Learning: How my most recent adult learning class evolved, and why I’m glad it did.May 19: Spring 2017 Reflections: The Short Story—Online: The series concludes with a few takeaways from my first experience teaching an all-online class.May 20-21: Summer and Fall 2017 Previews: Previews of the new or heavily revised courses I’ll be teaching this summer and fall—I’d love to hear about what’s next for you!May 22: Star Wars Studying: A Cross-Cultural Force: A Star Wars 40th anniversary series starts with how the first film was inspired by international texts, and why that’s a good thing.May 23: Star Wars Studying: The Force Awakens and Marketing: The series continues with two things I love about the first film in the new trilogy, and why it worries me a bit.May 24: Star Wars Studying: Rogue One, Diversity, and War: Two ways the newest film pushed the envelope for the franchise, as the series rolls on.May 25: Star Wars Studying: Yoda, Luke, and Love: What the wise Jedi Master got wrong about the Force, and why the opposite lesson matters so much.May 26: Star Wars Studying: The Thrawn Trilogy: The series continues with what Timothy Zahn’s novels can help us understand about genre storytelling.May 27-28: Matthew Teutsch’s Guest Post: Five African American Books We Should All Read: My latest Guest Post highlights five vital African American texts and authors.May 29: Better Remembering Memorial Day: My annual Memorial Day post kicks off a Decoration Day series.May 30: Decoration Day Histories: Frederick Douglass: The series continues with one of the great American speeches and why it’s so relevant today.May 31: Decoration Day Histories: Roger Pryor: The invitation and speech that mark two shifts in American attitudes, as the series rolls on.June 1: Decoration Day Histories: “Rodman the Keeper”: How a Constance Fenimore Woolson short story can help us remember a community for whom the holiday didn’t shift.June 2: Decoration Day Histories: So What?: The series concludes with three arguments for remembering Decoration Day alongside Memorial Day.Next series starts Monday,BenPS. Topics you’d like to see covered in this space? Guest Posts you’d like to contribute? Lemme know!

Published on June 03, 2017 03:00

June 2, 2017

June 2, 2017: Decoration Day Histories: So What?

[Following up Monday’s Memorial Day special, a series on some of the complex American histories connected to the holiday’s original identity as Decoration Day.]On three ways to argue for remembering Decoration Day as well as Memorial Day.If someone (like, I dunno, an imaginary voice in my head to prompt this post…) were to ask me why we should better remember the histories I’ve traced in this week’s posts—were, that is, to respond with the “So what?” of today’s title—my first answer would be simple: because they happened. There are many things about history of which we can’t be sure, nuances or details that will always remain uncertain or in dispute. But there are many others that are in fact quite clear, and we just don’t remember them clearly: and the origins and initial meanings of Decoration Day are just such clear historical facts. Indeed, so clear were those Decoration Day starting points that most Southern states chose not to recognize the holiday at all in its early years. I can’t quite imagine a good-faith argument for not better remembering clear historical facts (especially when they’re as relevant as the origins of a holiday are on that holiday!), and I certainly don’t have any interest in engaging with such an argument.But there are also other, broader arguments for better remembering these histories. For one thing, the changes in the meanings and commemorations of Decoration Day, and then the gradual shift to Memorial Day, offer a potent illustration of the longstanding role and power of white supremacist perspectives (not necessarily in the most discriminatory or violent senses of the concept, but rather as captured by that Nation editorial’s point about the negro “disappearing from the field of national politics”) in shaping our national narratives, histories, and collective memories. In my adult learning class a few semesters back I argued for what I called a more inclusive vs. a more exclusive version of American history, one that overtly pushes back on those kinds of narrow, exclusionary, white supremacist historical narratives in favor of a broader and (to my mind) far more accurate sense of all the American communities that have contributed to and been part of our identity and story. Remembering Decoration Day as well as Memorial Day would represent precisely such an inclusive rather than more exclusive version of American history.There’s also another way to think about and frame that argument. Throughout the last few years, conservatives have argued that the new Common Core and AP US History standards portray and teach a “negative” vision of American history, rather than the celebratory one for which these commentators argue instead. As those hyperlinked articles suggest, these arguments are at best oversimplified, at worst blatantly inaccurate. But it is fair to say that better remembering painful histories such as those of slavery, segregation, and lynching can be a difficult process, especially if we seek to make them more central to our collective national memories. So the more we can find inspiring moments and histories, voices and perspectives, that connect both to those painful histories and to more ideal visions of American identity and community, the more likely it is (I believe) that we will remember them. And I know of few American histories more inspiring than that of Decoration Day: its origins and purposes, its advocates like Frederick Douglass, and its strongest enduring meaning for the African American community—and, I would argue, for all of us.May 2017 recap this weekend,BenPS. What do you think?

Published on June 02, 2017 03:00

June 1, 2017

June 1, 2017: Decoration Day Histories: “Rodman the Keeper”

[Following up Monday’s Memorial Day special, a series on some of the complex American histories connected to the holiday’s original identity as Decoration Day.]On the text that helps us remember a community for whom Decoration Day’s meanings didn’t shift.In Monday’s post, I highlighted a brief but important scene in Constance Fenimore Woolson’s short story “Rodman the Keeper” (1880). John Rodman, Woolson’s protagonist, is a (Union) Civil War veteran who has taken a job overseeing a Union cemetery in the South; and in this brief but important scene, he observes a group of African Americans (likely former slaves) commemorate Decoration Day by leaving tributes to those fallen Union soldiers. Woolson’s narrator describes the event in evocative but somewhat patronizing terms: “They knew dimly that the men who lay beneath those mounds had done something wonderful for them and for their children; and so they came bringing their blossoms, with little intelligence but with much love.” But she gives the last word in this striking scene to one of the celebrants himself: “we’s kep’ de day now two years, sah, befo’ you came, sah, an we’s teachin’ de chil’en to keep it, sah.”“Rodman” is set sometime during Reconstruction—perhaps in 1870 specifically, since the first Decoration Day was celebrated in 1868 and the community has been keeping the day for two years—and, as I noted in yesterday’s post, by the 1876 end of that historical period the meaning of Decoration Day on the national level had begun to shift dramatically. But as historian David Blight has frequently noted, such as in the piece hyperlinked in my intro section above and as quoted in this article on Blight’s magisterial book Race and Reunion (2002), the holiday always had a different meaning for African Americans than for other American communities, and that meaning continued to resonate for that community through those broader national shifts. Indeed, it’s possible to argue that as the national meaning shifted away from the kinds of remembrance for which Frederick Douglass argued in his 1871 speech, it became that much more necessary and vital for African Americans to practice that form of critical commemoration (one, to correct Woolson’s well-intended but patronizing description, that included just as much intelligence as love).In an April 1877 editorial reflecting on the end of Reconstruction, the Nation magazine predicted happily that one effect of that shift would be that “the negro will disappear from the field of national politics. Henceforth the nation, as a nation, will have nothing more to do with him.” Besides representing one of the lowest points in that periodical’s long history, the editorial quite clearly illustrates why the post-Reconstruction national meaning of Decoration Day seems to have won out over the African American one (a shift that culminated, it could be argued, in the change of name to Memorial Day, which began being used as an alternative as early as 1882): because prominent, often white supremacist national voices wanted it to be so. Which is to say, it wasn’t inevitable that the shift would occur or the new meaning would win out—and while we can’t change what happened in our history, we nonetheless can (as I’ll argue at greater length tomorrow) push back and remember the original and, for the African American community, ongoing meaning of Decoration Day.Last Decoration Day history tomorrow,BenPS. What do you think?

Published on June 01, 2017 03:00

May 31, 2017

May 31, 2017: Decoration Day Histories: Roger Pryor

[Following up Monday’s Memorial Day special, a series on some of the complex American histories connected to the holiday’s original identity as Decoration Day.]On the invitation and speech that mark two shifts in American attitudes.In May 1876, New York’s Brooklyn Academy of Music invited Confederate veteran, lawyer, and Democratic politician Roger A. Pryor to deliver its annual Decoration Day address. As Pryor noted in his remarks, the invitation was most definitely an “overture of reconciliation,” one that I would pair with the choice (earlier that same month) of Confederate veteran and poet Sidney Lanier to write and deliver the opening Cantata at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Indeed, reunion and reconciliation were very much the themes of 1876, threads that culminated in the contested presidential election and the end of Federal Reconstruction that immediately followed it (and perhaps, although historians have different perspectives on this point, stemmed from that election’s controversial results). In any case, this was a year in which the overtures of reconciliation were consistently heard, and we could locate Pryor’s address among the rest.Yet the remarks that Pryor delivered in his Decoration Day speech could not be accurately described as reconciliatory—unless we shift the meaning to “trying to reconcile his Northern audiences with his Confederate perspective on the war, its causes and effects, and both regions.” Pryor was still waiting, he argued, for “an impartial history” to be told, one that more accurately depicted both “the cause of secession” and Civil War and the subsequent, “dismal period” of Reconstruction. While he could not by any measure be categorized as impartial, he nonetheless attempted to offer his own version of those histories and issues throughout the speech—one designed explicitly, I would argue, to convert his Northern audience to that version of both past and present. Indeed, as I argue at length in my first book, narratives of reunion and reconciliation were quickly supplanted in this period by ones of conversion, attempts—much of the time, as Reconstruction lawyer and novelist Albion Tourgée noted in an 1888 article, very successful attempts at that—to convert the North and the nation as a whole to this pro-Southern standpoint.In my book’s analysis I argued for a chronological shift: that reunion/reconciliation was a first national stage in this period, and conversion a second. But Pryor’s Decoration Day speech reflects how the two attitudes could go hand-in-hand: the Northern invitation to Pryor could reflect, as he noted, that attitude of reunion on the part of Northern leaders; and Pryor’s remarks and their effects (which we cannot know for certain in this individual case, but which were, as Tourgée noted, quite clear in the nation as a whole) could both comprise and contribute to the attitudes of conversion to the Southern perspective. And in any case, it’s important to add that both reconciliation and conversion differ dramatically from the original purpose of Decoration Day, as delineated so bluntly and powerfully by Frederick Douglass in his 1871 speech: remembrance, of the Northern soldiers who died in the war and of the cause for which they did so. By 1876, it seems clear, that purpose was shifting, toward a combination of amnesia and propaganda, of forgetting the war’s realities and remembering a propagandistic version of them created by voices like Pryor’s.Next Decoration Day history tomorrow,BenPS. What do you think?

Published on May 31, 2017 03:00

May 30, 2017

May 30, 2017: Decoration Day Histories: Frederick Douglass

[Following up Monday’s Memorial Day special, a series on some of the complex American histories connected to the holiday’s original identity as Decoration Day.]On one of the great American speeches, and why it’d be so important to add to our collective memories.In a long-ago guest post on Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Atlantic blog, Civil War historian Andy Hall highlighted Frederick Douglass’s amazing 1871 Decoration Day speech (full text available at that first hyperlink). Delivered at Virginia’s Arlington National Cemetery, then as now the single largest resting place of U.S. soldiers, Douglass’s short but incredibly (if not surprisingly) eloquent and pointed speech has to be ranked as one of the most impressive in American history. I’m going to end this first paragraph here so you can read the speech in full (again, it’s at the first hyperlink above), and I’ll see you in a few.Welcome back! If I were to close-read Douglass’s speech, I could find choices worth extended attention in every paragraph and every line. But I agree with Hall’s final point, that the start of Douglass’s concluding paragraph—“But we are not here to applaud manly courage, save as it has been displayed in a noble cause. We must never forget that victory to the rebellion meant death to the republic”—is particularly noteworthy and striking. Granted, this was not yet the era that would come to be dominated by narratives of reunion and reconciliation between the regions, and then by ones of conversation to the Southern perspective (on all of which, see tomorrow’s post); an era in which Douglass’s ideas would be no less true, nor in which (I believe) he would have hesitated to share them, but in which a Decoration Day organizing committee might well have chosen not to invite a speaker who would articulate such a clear and convincing take on the causes and meanings of the Civil War. Yet even in 1871, to put that position so bluntly and powerfully at such an occasion would have been impressive for even a white speaker, much less an African American one.If we were to better remember Douglass’s Decoration Day speech, that would be one overt and important effect: to push back on so many of the narratives of the Civil War that have developed in the subsequent century and a half. One of the most frequent such narratives is that there was bravery and sacrifice on both sides, as if to produce a leveling effect on our perspective on the war—but as Douglass notes in the paragraph before that conclusion, recognizing individual bravery in combat is not at all the same as remembering a war: “The essence and significance of our devotions here today are not to be found in the fact that the men whose remains fill these graves were brave in battle.” I believe Douglass here can be connected to Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, and its own concluding notion of honoring the dead through completing “the unfinished work”: “It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us.” That work and task remained unfinished and great long after the Civil War’s end, after all—and indeed remain so to this day in many ways. Just another reason to better remember Frederick Douglass’s Decoration Day speech.Next Decoration Day history tomorrow,BenIPS. What do you think?

Published on May 30, 2017 03:00

May 29, 2017

May 29, 2017: Better Remembering Memorial Day

[This special post is the first of a series inspired by the history behind Memorial Day. Check out my similar 2012 and 2014 series for more!]

On what we don’t remember about Memorial Day, and why we should.

In a long-ago post on the Statue of Liberty, I made a case for remembering, and engaging much more fully, with what the Statue was originally intended, by its French abolitionist creator, to symbolize: the legacy of slavery and abolitionism in both America and France, the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the memories of what he had done to advance that cause, and so on. I tried there, hopefully with some success, to leave ample room for what the Statue has come to mean, both for America as a whole and, more significantly still, for generation upon generation of immigrant arrivals to the nation. I think those meanings, especially when tied to Emma Lazarus’ poem and its radically democratic and inclusive vision of our national identity, are beautiful and important in their own right. But how much more profound and meaningful, if certainly more complicated, would they be if they were linked to our nation’s own troubled but also inspiring histories of slavery and abolitionism, of sectional strife and Civil War, of racial divisions and those who have worked for centuries to transcend and bridge them?

I would say almost exactly the same thing when it comes to the history of Memorial Day. For the last century or so, at least since the end of World War I, the holiday has meant something broadly national and communal, an opportunity to remember and celebrate those Americans who have given their lives as members of our armed forces. While I certainly feel that some of the narratives associated with that idea are as simplifying and mythologizing and meaningless as many others I’ve analyzed here—“they died for our freedom” chief among them; the world would be a vastly different, and almost certainly less free, place had the Axis powers won World War II (for example), but I have yet to hear any convincing case that the world would be even the slightest bit worse off were it not for the quarter of a million American troops who lives were wasted in the Vietnam War (for another)—those narratives are much more about politics and propaganda, and don’t change at all the absolutely real and tragic and profound meaning of service and loss for those who have done so and all those who know and love them. One of the most pitch-perfect statements of my position on such losses can be found in a song by (surprisingly) Bruce Springsteen; his “Gypsy Biker,” from Magic (2007), certainly includes a strident critique of the Bush Administration and Iraq War, as seen in lines like “To those who threw you away / You ain’t nothing but gone,” but mostly reflects a brother’s and family’s range of emotions and responses to the death of a young soldier in that war.

Yet as with the Statue, Memorial Day’s original meanings and narratives are significantly different from, and would add a great deal of complexity and power to, these contemporary images. The holiday was first known as Decoration Day, and was (at least per the thorough histories of it by scholars like David Blight) originated in 1865 by a group of freed slaves in Charleston, South Carolina; the slaves visited a cemetery for Union soldiers on May 1st of that year and decorated their graves, a quiet but very sincere tribute to what those soldiers have given and what it had meant to the lives of these freedmen and –women. The holiday quickly spread to many other communities, and just as quickly came to focus more on the less potentially divisive, or at least less complex as reminders of slavery and division and the ongoing controversies of Reconstruction and so on, perspectives of former soldiers—first fellow Union ones, but by the 1870s veterans from both sides. Yet former slaves continued to honor the holiday in their own way, as evidenced by a powerful scene from Constance Fenimore Woolson’s “Rodman the Keeper” (1880), in which the protagonist observes a group of ex-slaves leaving their decorations on the graves of the Union dead at the cemetery where he works. On the one hand, these ex-slave memorials are parallel to the family memories that now dominate Memorial Day, and serve as a beautiful reminder that the American family extends to blood relations of very different and perhaps even more genuine kinds. But on the other hand, the ex-slave memorials represent far more complex and in many ways (I believe) significant American stories and perspectives than a simple familial memory; these acts were a continuing acknowledgment both of some of our darkest moments and of the ways in which we had, at great but necessary cost, defeated them.Again, I’m not trying to suggest that any current aspects or celebrations of Memorial Day are anything other than genuine and powerful; having heard some eloquent words about what my Granddad’s experiences with his fellow soldiers had meant to him (he even commandeered an abandoned bunker and hand-wrote a history of the Company after the war!), I share those perspectives. But as with the Statue and with so many of our national histories, what we’ve forgotten is just as genuine and powerful, and a lot more telling about who we’ve been and thus who and where we are. The more we can remember those histories too, the more complex and meaningful our holidays, our celebrations, our memories, and our futures will be.Series continues tomorrow,BenPS. What do you think?

Published on May 29, 2017 03:00

May 27, 2017

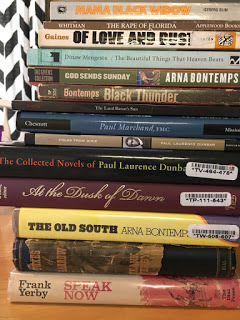

May 27-28, 2017: Matthew Teutsch’s Guest Post: Five African American Books We Should All Read

[Matthew Teutsch is a scholar of American, African American, and Southern literature, and Rhetoric and Composition. He blogs at Interminable Rambling, as well as the AAIHS’s Black Perspectives site, and is a prolific Tweeter.]

I’m one of those people that typically remembers when and where I first pick up a book or record. I used to recall with fondness the time and place I got a CD. Remember those? I could tell you where I was the first time I heard Radiohead’s Kid A (in the car at a bank teller window with one of those cassette adaptors for a portable CD player). The same goes for most books that I read too. Typically, I stumble upon these books not knowing what to expect. At other times, I have some idea about what I’m in store for before I even begin to read the first page. I want to take you on a journey into the past where I will tell you about some of the books and authors I’ve read that I think need to be picked up, read and reexamined. My research focuses on African American literature, so this list consists of five African American works that we need to reconsider.

Arna Bontmemps’ The Old South (1973)

Even though I’m from Louisiana, I had never read any work by Bontemps until I graduated with my PhD. I had a professor who actually left Bontemps’ novel Black Thunder (1936) in my mailbox as he was decluttering his office. I read Bontemps’ narrative of Gabriel Proser’s failed slave rebellion then picked up his novel about the Hattian Revolution, Drums at Dusk (1939), from the library, and found God Sends Sunday (1931) in a Barnes & Noble in Columbus, OH, during a National Endowment for the Humanities summer institute on Paul Laurence Dunbar (more on him later). All of Bontemps’ work needs to be read, including his nonfiction. However, I would suggest that we begin by looking at his collection of short stories The Old South, a book that appeared the same year he passed away. The book collects stories about the South and the African American experience, layered with folklore, religion, pain, suffering, and joy. His most well-known story, “A Summer Tragedy” appears alongside stories such as “Heathen at Home” and “Mr. Kelso’s Lion,” two pieces that explore white liberalism and white supremacy. Along with these stories, the collection includes Bontemps’ essay “Why I Returned (A Personal Essay),” a piece that needs to be read and considered in relation to works by authors such as Ernest J. Gaines and Alice Walker who write about returning to the South, and even in relation to authors like Richard Wright who write about leaving it. Unfortunately, The Old South is no longer in print, so the only option to get a copy is to either find one in the library or order one online. I got lucky by purchasing a copy for under $5.00. My goal is to get The Old South back in print so more people can study his short stories along with his novels.

Frank Yerby Speak Now (1969)

Every time the Friends of the Library had a sale in Lafayette, LA, I would be there ready to spend time searching through the countless books for ones that would set on my shelf. Without fail, I would always find first editions of Frank Yerby’s books at the sale, and I would always buy them. Yerby wrote 33 novels, numerous short stories, and poems. Even though he is one of the bestselling African American authors of all time, scholars have somewhat ignored him, or he becomes a guilty pleasure. Robert Bone once referred to Yerby as the “prince of the pulpsters.” To a certain extent, this label fits Yerby; however, we need to look past his “costume novel” exterior and peel back the layers that make up his works. For me, this began when I found Speak Now in a bookstore in New Orleans in the fall of 2015. I already had numerous books by Yerby on my shelf, but I had never read one yet. I couldn’t pass up buying another first edition Yerby, so I looked at the cover where an African American man and a white woman stared back at me as revolutionaries charged towards the right of the cover in the background. This was nothing like the “genteel” covers of his other novels. In fact, far from being, as some have termed him, placating to his white readers, Yerby attacks ideas of beauty, identity, interracial relationships, and postcolonial issues in a narrative that, while at times heavy-handed, clearly counters much of the criticism that critics and scholars lobbied against him. He followed Speak Now up with two books about an African man named Hwesu in The Dahomean (1971), which takes place entirely in Africa, and in A Darkness at Ingraham’s Crest (1979) which sees Hwesu as a slave in the Deep South. I would suggest, if you want to read Yerby, start with Speak Now and look back at his numerous “costume novels” such as The Foxes of Harrow (1946), The Vixens (1947), Benton’s Row (1954), and others to see the ways that Yerby confronts whites and subverts their ideas subtly through his narratives.

Albery Allson Whitman The Rape of Florida or Twasinta’s Seminoles (1884)

Unlike the other works on this list, I do not recall the exact moment I discovered Albery Allson Whitman. I do know that I found him while working on my dissertation. His work interested me partly because he wrote epic poems and explored the intersections between Native Americans and African Americans during the latter part of the nineteenth century. Not A Man, and Yet A Man (1877) focuses on the Midwest and Fort Dearborne, and The Rape of Floridacenters around the Seminole Wars. Whitman was not the only author of the period to explore these junctions, Pauline Hopkins did as well in Winona: A Tale of Negro Life in the South and Southwest (1902). What struck me about The Rape of Florida, apart from it being about Spanish settlers, runaway slaves from Georgia, and the Seminole, was Whitman’s decision to write the epic poem in Spenserian stanzas. This, along with the epic nature, intrigued me, and led me to do more research on him. James Weldon Johnson claims Whitman as the best African American poet between Phyllis Wheatley and Paul Laurence Dunbar, and he appeared in numerous anthologies through about the 1970s when he, along with other authors such as John Marrant and John Russwurm started to disappear as well. Like other authors during the Nadir, we need to reexamine Whitman’s work. At this time, the most recent book that I know of that explores Whitman in detail is Ivy Wilson’s At The Dusk of Dawn (2009). Whitman’s entire oeuvre is important because it provides us with a link from earlier African American poets to Dunbar. In fact, Dunbar and Whitman both read at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, and Dunbar had a signed copy of The Rape of Florida in his library in Dayton, Ohio.

Paul Laurence Dunbar The Fanatics (1901)

In the summer of 2015, I participated in an NEH Summer Institute on Paul Laurence Dunbar. I applied for a couple of reasons; one of the main reasons was because I wanted to continue my work on Whitman, so exploring the connections between Dunbar and Whitman would be an important aspect of that project. Before going to Ohio, I did not realize how prolific Dunbar was during his short life. He started his own newspaper with the Wright brothers while in high school, wrote numerous volumes of short stories, wrote plays, and wrote four novels. This is not including his poetry, newspaper writings, and speeches. Most people only know a handful of poems Dunbar wrote, the ones that appear in anthologies or collections; however, to understand the full picture of Dunbar’s work, we need to look at everything. For me, the short stories are fertile ground for exploration, along with the novels. Like Yerby, three of his four novels center on white characters, while African American characters exist in the background, and The Love of Landry (1900) even takes place in the West, Colorado to be exact. While interesting in their own rights, The Fanatics presents readers with two families in Ohio that have a falling out when the Civil War breaks out. One family is from the North and the other is from the South. We need to consider this novel in relation to other reconciliation novels of the period. We can even think about this novel as a migration narrative; at one point, blacks come North to Ohio and experience inter and intraracial oppression. As Herbert Woodward Martin, Ronald Primeau, and Gene Andrew Jarrett say, the move and “[t]he resistance of Stothard and many like him forecasts the modern African American ‘ghetto.’”

Attica Locke The Cutting Season (2012)

I first heard about Attica Locke when she won the Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellencein 2103. For me, The Cutting Seasoncaused me to think about the numerous ways that we examine and “preserve” history. Considering discussions surrounding the Confederate Battle Flag in 2015 and the current conversations around the monuments in New Orleans, Locke’s novel interrogates these sites and images of history that we continually encounter on a day-to-day basis. Specially, Locke explores how we react to the plantation homes that dot the Southern landscape, especially in Louisiana. Taking place right outside of Baton Rouge, on the River Road, The Cutting Season is a mystery novel where the past and the present collide. The narrative revolves around Caren Gray, an African American woman who went to college but returned to Belle Vie Plantation to manage it. Her ancestors, and those who owned her ancestors, lived and died on the same land that she oversees now. Throughout, Locke calls upon readers to question the language we use to describe the past and to interrogate the ways we remember that history. As well, Locke looks at the ways workers, specifically migrant workers, become exploited in the present. The woman that Caren finds murdered, Inès, is an undocumented migrant worker who left her family so she could make money to help them survive. In many ways, Inès’ story presents a similar narrative to that of Gaines in his own life and in his novels. Locke’s book needs to be read within the context of authors like Gaines, Walker, Morrison, and Sherley Anne Williams.

There are many more underread novels and texts that I could talk about here, but I think five is enough to get started with. Here are more texts if you are interested in reading more works that we need to reexamine or even begin to examine. I hope you enjoyed this list. Let me know what you think about these books and authors on Twitter @SilasLapham.

[Next series starts Monday,BenPS. What do you think? Other books you’d share?]

[Next series starts Monday,BenPS. What do you think? Other books you’d share?]

Published on May 27, 2017 03:00

May 26, 2017

May 26, 2017: Star Wars Studying: The Thrawn Trilogy

[May 25thwill mark the 40th anniversary of the release of the first Star Wars film (it wasn’t titled A New Hope at that point!). So this week I’ll offer a few ways to AmericanStudy the iconic series and its contexts and connections. Share your own different points of view for a force-full crowd-sourced weekend post, my fellow padawan learners!]On what Timothy Zahn’s Star Wars novels meant to fans, and what that can help us analyze about genre storytelling.It’s very difficult to explain to my sons, growing up as they are in the era not only of the new Star Wars films, but of the Clone Wars and Rebels animated series, of numerous Star Wars video games, and even of Star Wars amusement parks for crying out loud, how much of a void there was for a young Star Wars fan in the years after Return of the Jedi(1984). I was almost 7 when Jedi came out, just coming into my own as a full-fledged Star Wars fan; the next new film, The Phantom Menace, wouldn’t be released until 1999, when I was about to turn 22 and not quite in the same place as that 7 year old StarWarsStudier had been. Although George Lucas tried to bridge the gap by re-releasing the original trilogy with new footage in the 1990s (not all of it uniformly awful, although I still shudder in horror every time I have to watch Han Solo step on Jabba the Hutt’s tail in that inserted New Hope sequence), I think it’s fair to say that if we fans had been left with no new Star Wars stories between Jedi and Phantom, many of us might have left the Star Wars universe behind for fresher storytelling pastures.But we weren’t left so bereft, and the main reasons were the three novels in science fiction writer Timothy Zahn’s Thrawn trilogy: Heir to the Empire (1991), Dark Force Rising (1992), and The Last Command (1993). There had been novelizations and comic book versions of the films, but Zahn’s books, set five years after the events of Return of the Jediand featuring both returning and new characters, were the first truly new literary stories set in the Star Wars universe, creating (or at least popularizing) the now-familiar concept of the “expanded universe.” This teenage AmericanStudier had already read and loved plenty of fantasy and science fiction books and series by the time Heir to the Empire appeared, but there was nonetheless something different about such expanded universe books, something particularly potent in the way they (that is, the way Zahn) blended the familiar with the new, built on a world and characters and settings we knew and cared about while taking them and us in unfamiliar and uncertain directions. Clearly that wasn’t just me; Heir to the Empire was a #1 New York Timesbestseller, the trilogy sold a combined 15 million copies (to date), and the books’ popularity has even been credited by one Star Wars historian (Michael Kaminsky) with helping convince George Lucas to make the prequel films.So what might we make of those effects, of the potent cultural role of Zahn’s Star Wars novels? Much of what my Fitchburg State colleague Heather Urbanski argues in her study The Science Fiction Reboot: Canon, Innovation, and Fandom in Refashioned Franchises (2013) is certainly relevant to that question; Urbanski counter critiques of reboots or sequels as unoriginal, arguing instead that such works, and franchises overall, tap into audience desires and needs in profound ways. I would agree with all of that, but would also suggest that there’s something specific to novels and their form of storytelling that was also at play in the role and success of Zahn’s Star Wars books. Of course multi-episode TV shows can expand a universe in their own ways, as we’ve seen with the recent Star Wars shows (characters from which have, tellingly, made their way into the most recent films). Yet—and I grant that this might be the literary scholar in me talking—I would argue that a novel can expand and deepen a cinematic universe in ways that no other genre can, and that it’s thus far from coincidental that it was Zahn’s Thrawn novels that first truly opened up not only the Star Wars Expanded Universe, but even the concept of an expanded universe at all. They certainly had a distinct and vital effect for this StarWarsStudier.Crowd-sourced post this weekend,BenPS. So one more time: what do you think? Other Star Wars contexts you’d highlight?

Published on May 26, 2017 03:00

May 25, 2017

May 25, 2017: Star Wars Studying: Yoda, Luke, and Love

[May 25thwill mark the 40th anniversary of the release of the first Star Wars film (it wasn’t titled A New Hope at that point!). So this week I’ll offer a few ways to AmericanStudy the iconic series and its contexts and connections. Share your own different points of view for a force-full crowd-sourced weekend post, my fellow padawan learners!]On what the wisest Jedi Master got very wrong, and why the opposite lesson matters so much.As the dutiful father to two Star Wars-obsessed sons, I’ve now watched the prequel trilogy many more times than I would have ever chosen to on my own (once was more than enough, to be honest). If I had to pin down the precise scene that epitomizes the failings of those three films, I would point not to obvious choices like Jar Jar Binks or “I don’t like sand” (although yes and yes), but instead to this weighty conversationbetween Yoda and Anakin Skywalker (Hayden Christensen) in Revenge of the Sith. For one thing, this CGI-version of Yoda looks infinitely less real than did the original trilogy’s puppet; I know we’re talking about a puppet green alien, but the scene is meant to be hugely emotional, and the feel of the characters matters. But more importantly, Yoda’s response to and advice for Anakin in this scene are uniformly terrible; this young man is terrified of losing a loved one, and Yoda tells him that the way of the Force and Jedi mean he should be happy if those he loves dies. Even if that’s officially true, Yoda should be able to sense how much it’s the opposite of what Anakin needs to hear at this moment; that he can’t makes me second-guess his role as Jedi Master and teacher to Luke in the original trilogy as well (and thus, yes, slightly ruins my childhood).But the thing is, Yoda isn’t just wrong here about human nature or what the immensely powerful and deeply frightened young man sitting before him desperately needs; he’s also wrong about the Force and the Jedi. My evidence? None other than Luke Skywalker, and the most important actions in the entire series to date: those that result in turning Darth Vader back to the light side, destroying the Emperor, and helping save the universe. Luke took all those actions because he still loved his father and sensed the reciprocal love in him (despite Yoda’s assertion that Jedi aren’t supposed to love), and because he didn’t want to let his father (or his sister Leia, friend Han, and other loved ones) die without trying to save him. And Darth responded in kind for the same reasons: he did in fact still love his son, and didn’t want to let him die when the Emperor was on the brink of killing him. All of these most heroic actions are driven by precisely the kinds of deep and defining emotions that Yoda had argued are antithetical to the Jedi Order—and yet who could possibly argue with Luke when he says, amidst that final confrontation with the Emperor and shortly before his father saves him, “I am a Jedi, like my father before me”?My point here isn’t just to argue with Yoda or display the silliness of the prequels (although if you watch them as much as I have, you’ll understand both impulses, I assure you). No, my point is that the Force itself, as portrayed by the original trilogy (and almost entirely misunderstood by the prequels), is quite literally love. That might seem mushy or reductive, but I think it’s actually a great lens through which to analyze what motivates some of the most vital and heroic characters in epic fantasy stories: Sam’s love for Frodo; Severus Snape’s love for Lily (Evans) Potter; Willow Ufgood’s love for Elora Danan; and the list goes on. On the one hand, this recurring storytelling thread grounds and humanizes these fantastic stories, linking them to one of the most shared and universal elements of our humanity. But at the same time, the thread elevates love, making it into a force that can change and shape and save worlds, can defeat the most powerful evils. Seen in this light, the ubiquitous family relationships between so many characters in the Star Wars universe aren’t just coincidence or storytelling shorthand; they’re a symbolic reflection of the love that links us to one another, that “surrounds us, and penetrates us, and binds the galaxy together.” A lesson Yoda, like all of us, could stand to learn.Last StarWarsStudying tomorrow,BenPS. What do you think? Other Star Wars contexts you’d highlight?

Published on May 25, 2017 03:00

Benjamin A. Railton's Blog

- Benjamin A. Railton's profile

- 2 followers

Benjamin A. Railton isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.