Lea Wait's Blog, page 12

June 15, 2025

Writing Tools I Use

Rob Kelley here, and I’ll start with a writing conference shout-out. I’m just back from The Writer’s Hotel 2025, held right here in Maine at the Sebasco Harbor Resort. The conference was wonderful, with craft sessions, readings by workshop participants and faculty, and extraordinarily useful workshop sessions reviewing our work. (My workshop helped me figure out a character introduction that I knew wasn’t working, which was AWESOME!).

The quality of the faculty and of the workshop participants is incredibly high, which makes it all that much more productive (and fun). These are the same folks who run High Frequency Press, my publisher for Raven (2025) and Critical State (2026).

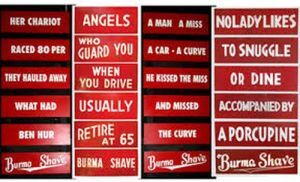

A tool I do not use!

One of the discussions I had with my fellow workshop attendees was about what tools we all use when we write, which I find interesting because folks differ widely on what works (and doesn’t) for them.

My work starts in Evernote, a cloud-based note taking system. In there I have a whole story ideas file (and a blog ideas file!). When I get an idea for a book, I open a new note and start by adding some typical sections: Outline, Comps, Titles, and Research.

The outline evolves as I think more about the book, adding characters and plot arcs. Comps and Titles get filled in as I go, and can change as the book evolves. Research is what it sounds like, links to research on the place, the plot, the characters’ professions, law enforcement matters, a huge variety. Some of that research is never used, some has to be added to later as the book comes together.

When I’m ready to start writing I open up a new file in Scrivener. I’ve really come to like it as a drafting tool. I give each scene its own new text container, title (which is only for me to help remember it), and color code icon that shows whose POV it is in. This makes it easy to move things around as the book evolves, to make sure I’ve got good alternating POV voices, and to structure the book’s longer character and plot arcs.

When I think the book is ready to be edited, I compile it from Scrivener into Word where I start my detailed edits. I have a “Tic List” in Evernote that has a list of words I overuse and edits I need to actively make: adverbs that don’t do real work, passive voice, random interjections, overused articles, profanity (always too much!), etc.

Then I use the Word read-aloud feature. It’s amazing what you find when you hear your work read out loud. I don’t read it aloud myself not because I’m lazy (well, mostly not because I’m lazy), but because when I read I’ll sometimes correct grammar or word choice as I go, but when I hear it from my laptop, I catch it.

One thing I don’t do any more is use “editing tools” like Autocrit or Grammarly. Not because I am uncomfortable that they’ll AI scrape my text (they say they don’t) but because conscious editing by hand makes me more involved in the manuscript.

Only then would I share work with a beta reader, whose input is so, so valuable, as was the input from my workshop peers.

What tools work for you?

June 13, 2025

Weekend Update: June 14-15, 2025

Next week at Maine Crime Writers there will be posts by Rob Kelley (Monday), Kaitlyn Dunnett/Kathy Lynn Emerson (Tuesday), Kate Flora (Thursday), and Matt Cost (Friday).

Next week at Maine Crime Writers there will be posts by Rob Kelley (Monday), Kaitlyn Dunnett/Kathy Lynn Emerson (Tuesday), Kate Flora (Thursday), and Matt Cost (Friday).

In the news department, here’s what’s happening with some of us who blog regularly at Maine Crime Writers:

Belatedly adding this, with congrats to Gabi.

An invitation to readers of this blog: Do you have news relating to Maine, Crime, or Writing? We’d love to hear from you. Just comment below to share.

And a reminder: If your library, school, or organization is looking for a speaker, we are often available to talk about the writing process, research, where we get our ideas, and other mysteries of the business, along with the very popular “Making a Mystery” with audience participation, and “Casting Call: How We Staff Our Mysteries.” We also do programs on Zoom. Contact Kate Flora

Four Things

Hi all,

Bear with me on this one. I’m not sure where I’m going but I have a lot to say.

[image error]One

On May 30, I attended the Maine Literary Awards. It was inspiring to see how much schools and organizations do to support young writers in Maine. I felt honored to live in a state that holds space for young people to speak and be heard.

What they have to say matters.

During his speech, Morgan Talty said that a story isn’t an answer, it’s a question, or maybe a series of questions that writers are asking themselves about humanity, about the world in which we live, about our place in that world.

I’m wondering, if you write, what are the questions you explore in your stories? Why?

[image error]Two

On Tuesday night I went to Print to hear a little about what Lori Ostlund had to say about her latest book Are You Happy? It was a pretty full house and I saw some familiar faces and Lori said a lot of things that I’m still thinking about. Lori explained that where she is from (Minnesota) people talk up to a point of tension or conflict, they pause, and then they resume the conversation after. What matters, she said, is not what is said, but what is silent. (Or something like that.)

The other thing I’m thinking about had to do with Lori’s ability to fold humor and sadness together because life is filled with both. When I write, she said, I cut to the bone.

I bought her book and I had her sign it and I think that is an accurate description of her writing.

When was the last time you listened to what wasn’t said? What did you learn?

[image error]Three

On Wednesday, my older son and I went out to dinner and played Gin Rummy with a deck of cards I keep in my purse, just in case. Which is, by the way, something I learned from my Abuelita who told me one that I should always travel with an extra pair of wool socks, enough cash (whatever that means), and a deck of cards. After dinner we went for a walk in the Western Cemetery, which smelled like the blossoms of the trees. We saw one gravestone for a man named Cobb who died in 1800 but was born in 1723. After a minute of staring, my son said, He lived through the birth of the country.

My oldest son is like that. For example, when he was in third grade he was really into sunken ships. So deep in that he was listening to sea shanties and that song about the Edmund Fitzgerald and making ships out of cardboard boxes and calling them Cardbordia. And one day he was staring into space and my sister said, What are you thinking about? And he said, All those people who died on the Titanic.

My sister will remind me of this every once in a while, when I am feeling especially frustrated by the preteen sass that lurks at the corners of conversations when he is tired or hungry or needs some time to himself.

After our walk, we went to see High Noon at Kinonik, which is down by the dock. It was a full house and there were a ton of reels lining the walls and a popcorn machine with little brown paper bags. The movie started with a teaser for the Big Sleep, with Bogart and Bacall, which was a special sort of nod because some of those Neo-westerns of the 50s creep into that noir space and get pretty comfortable.

High Noon holds up and says a bit about humanity that feels unfortunately relevant for all sorts of reasons that I won’t get into.

I’d be curious to hear your thoughts. What did you think?

[image error] Four

Registration for Crime Wave is officially open. I’m going and hope you can come, too. More HERE.

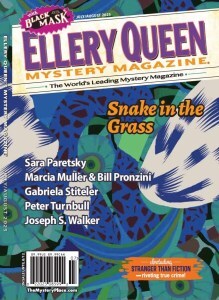

My short story “The Usual Reasons” is out in the July/August Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. You can grab a copy at your local Barnes and Nobel or Books A Million. Or you can get a digital version. Or even subscribe if you don’t already. More HERE.

Finally, I’m getting ready for a week of writing at the Hewnoaks Residency. I am honored to have received the Bodwell fellowship from the Maine Writers and Publishers Alliance.

Any recommendations on books to bring? Songs to listen to? Tricks to make the most of the time?

Hope our paths cross soon,

Gabi

June 11, 2025

Where Do You Get Your Ideas?

Vaughn

Vaughn Hardacker here: At some point in a writer’s career, they will be asked: Where Do You Get Your Ideas? It’s one of those questions that seems easy to answer until you’re standing before a group or sitting on a panel looking at the faces of an audience. My first impulse is to ask myself What humorous but insightful response can I give? The truth of the matter is that in my case, there is only one answer: The real world.

In my novel SNIPER, I was influenced by the D. C. sniper killings. In THE FISHERMAN, it was Robert Pickton, a Vancouver, B.C., killer who lamented that his quest to kill 50 women had come up just short at 49. The inspiration for Black Orchid was the 1947 Black Dahlia case.

Possibly, one of the best examples of places where a writer can gather ideas is how I learned about the Wendigo. In 1989, I was teaching at a vocational school, and the students had to write a technical paper. I had the class meet at the local library where they were to research their paper. To occupy myself, I wandered over to the anthropology section. I came across a book written by a Catholic missionary in the late 1800s. The section that interested me was the one on Native American myth and religion. The missionary was working with a tribe that was part of the Algonquin Nation located in northern Minnesota. The Algonquin-speaking people inhabited much of the northeastern corner of North America (from the Canadian Maritimes west to Minnesota). They called their gods Manitou. The most evil Manitou was the Wendigo. A cannibal who preyed on lost hunters (much of the myth was associated with the problem the people had with dealing with starvation in the winter months). The more a wendigo eats, the more it grows, which then requires it to eat more. The myth has the monster growing to a tremendous height. The missionary asked an old man: “Surely, you don’t believe that such a being exists?” The old Indian replied, “No I don’t … but I saw its tracks once.” The light in my head went on and resulted in my book (of which I’ve sold more than any other), WENDIGO.

Surprisingly enough, some of crime fiction’s most recognizable serial killers all came from a single source: a relatively unknown and diminutive reclusive named Edward Gein. Born at the turn of the century into the small farming community of Plainfield, Wisconsin, Gein lived a repressive and solitary life on his family homestead with a weak, ineffectual brother and a domineering mother who taught him from an early age that sex was a sinful thing. Eddie ran the family’s 160-acre farm on the outskirts of Plainfield until his brother Henry died in 1944 (it is believed that Edward killed his brother, but it has never been proven) and his mother in 1945. When she died, her son was a thirty-nine-year-old bachelor, still emotionally enslaved to the woman who had tyrannized his life. The rest of the house, however, soon degenerated into a madman’s shambles. Thanks to federal subsidies, Gein no longer needed to farm his land, so he abandoned it to take on odd jobs here and there for Plainfield residents, earning him a little extra cash. But he remained alone in the enormous farmhouse, haunted by the ghost of his overbearing mother, whose bedroom he kept locked and undisturbed, exactly as it had been when she was alive. He also sealed off the drawing room and five more upstairs rooms, living only in one downstairs room and the kitchen.

Ed Gein killer and grave robber.

Following her death in 1945, his mental health disintegrated. After Gein was apprehended as a suspect in a 1957 murder, the investigation of his home yielded a highly disturbed man who kept human organs and fashioned clothing and accessories out of body parts. He spent the rest of his life institutionalized, his story fueling the creation of such infamous movie characters as Norman Bates (Psycho), Jame Gumb (Buffalo Bill of The Silence of the Lambs), Leatherface (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre), as well as numerous lesser-known hack-and-slash horror movies.

Surprisingly, when compared to Ted Bundy, Gary Ridgeway (the Green River Killer), and the aforementioned Robert Pickton, Gein was more of a grave robber than a serial killer. He was convicted of two murders.

Under questioning, Gein confessed to killing Bernice Worden and, three years earlier, a woman named Mary Hogan. Additionally, he admitted to digging up numerous corpses for cutting off body parts, practicing necrophilia, and fashioning masks and suits out of skin to wear around the home. (I am underplaying the horrific extent of Gein’s psychosis, but an internet search on him will bring forth the full extent of his illness and resultant crimes.) With that sort of evidence, authorities attempted to connect him to other murders and disappearances from recent years, but were unable to draw any definitive conclusions.

In early 1968, Ed Gein was determined fit to finally stand trial. That November, he was found guilty of the murder of Bernice Worden. However, he was also found insane at the time of the murder, and as such, he was recommitted to Central State Hospital.

Gein’s Bedroom

Save for his attempt to petition for a release in 1974, which was rejected, the mild-mannered Gein made virtually no news while institutionalized. Later that decade, his health failing, he was transferred to the Mendota Mental Health Institute, where he died of cancer and respiratory illnesses on July 26, 1984.

As I write this, it becomes increasingly clear to me that there is a great deal of truth to the old saying: The truth is stranger than fiction.

Share this:

June 9, 2025

MORNING WALK AND WRITE/ EAST SIDE OF PORTLAND MAINE

JULE SELBO

Summer’s almost here and my office is getting hot. The sun starts pouring in an hour after sunrise – @ 5 am – and it is aggressive. The big blob sends biting, shiny light right across my desk, exactly – as I sit at my laptop – right into my eyeline.

Move your desk, stupid, you say. But – after the sun gets to a certain height in the sky – the placement is perfect.

And besides, I know the air outside is the coolest it’s going to be in my waking hours. So, walking shoes are put on and notebook and pens go into my bag (computer will be left at home unless I am walking only a few blocks) and the morning walk/write begins. I limit my choices to those under 2 miles from my home – the search is for a pretty empty spot where coffee and maybe an egg or muffin or pancake can be ordered, and the “white noise” of a hustle and bustle kitchen and a few customers can be had. The “white noise” is essential.

My favorite way to start my day: coffee and writing.

REGULAR HAUNTS

Becky’s 5 am 390 Commercial. Stools at the counter – plenty of space until 6:30 or so – sometimes later.

The Works 6 am – 15 Temple Street (close to Spring, close to the Nickelodeon Movie Theatre). IMO, they are among the best sandwich and salad providers this side of Portland. Order at the counter, there are usually only one – or none – people there so I have my favorite spot at a high-top window seat.

Double Great 6:30 am – 100 Congress Street. When I first moved to Portland, it was Hilltop Café and it’s where I met many in my neighborhood who are still my friends today. Friendly, warm, home-cooking Hilltop Café closed during Covid and it took a good year or two for Double Great to open. The owners take coffee, matcha, and hot chocolate seriously. Pastries are provided by an outside source. The place is populated with people on computers or reading books – but then starts to buzz around 8:15 am with those doing low-key business meet-ups and meeting friends/new acquaintances As tables fill – I leave.

Double Great 6:30 am – 100 Congress Street. When I first moved to Portland, it was Hilltop Café and it’s where I met many in my neighborhood who are still my friends today. Friendly, warm, home-cooking Hilltop Café closed during Covid and it took a good year or two for Double Great to open. The owners take coffee, matcha, and hot chocolate seriously. Pastries are provided by an outside source. The place is populated with people on computers or reading books – but then starts to buzz around 8:15 am with those doing low-key business meet-ups and meeting friends/new acquaintances As tables fill – I leave.

Bom Dia 7 am – – 47 India Street. Acai bowls with tons of fruit, bagels, smoothies and an array of different coffee options. Excellent tables and chairs to work at. There’s a nice stream of people coming in with or without their dogs to get their morning favorites and the tables do not fill until after 9 am.

Bard Coffee 7 am (8 am on Sunday) – 185 Middle Street. IMO, shares my award for the best drip coffee of my haunts. They get their pastries from an excellent bakery. This is a popular spot but until 8:30 to 9 am, there is no sense that you are overstaying a welcome. See “regulars” there every day – a playwright that I really like, a lawyer who is writing a book, a few bloggers.

Navis 7 am – 56 Thames (close to Ocean Gateway). Quiet until 9 ish. Regulars there every day. Nice and quiet until 9:30 or so. (Don’t know about after that, because I’m on my way – but when I walk by later in the day – lots of customers for sandwiches etc.)

Speckled Ax 7 am 18 Thames. Don’t really like the light here.

Coffee By Design 7 am 1 Diamond Street. It’s a farther walk for me and there’s that one extra hill that I like to avoid. So if it’s raining and I take the car – this is a great spot. Stays low key until 8:30 or so.

Forage 7 am 123 Washington Avenue. Very noisy and for me, not a “settled” noise – and I’m not fond of the tables and chairs. Great Great bagels – and the bagel sandwiches are amazing.

Lenora 7 am 2 Portland Square. One of my favorites. It’s more of a late night/late afternoon hang (drinks and tacos) so in the early morning there’s only a few regulars – or a few parents with young kids. Amazing place to work and

There are a few of us doing just that. But plenty of room. Coffee is great at Lenora’s. So lovely to sit here and work.

There are a few of us doing just that. But plenty of room. Coffee is great at Lenora’s. So lovely to sit here and work.

Salt Yard Café 7 am 285 Commercial Street. Connected to the hotel, so it gets busy with travellers.

Radial Coffee Co. 7 am 383 Commercial Street. NEW-ISH. Haven’t tried it yet. Across the street from Becky’s….

Porthole. 7 am. 20 Custom House Wharf. Classic old diner where the food and coffee takes a second seat to atmosphere. Friendly. Lots of regulars (who are non-writers/readers) and great atmosphere.

Cutie’s. 8 am 46 Market Street. New. Lots of people reading here, early morning. And on computers. Don’t have a good sense of it yet.

Tandem Coffee Roasters 8 am 122 Anderson Street. Too small to work at. Great coffee. But I am too aware that the seating is limited.

LB Kitchen 8 am 255 Congress. Lots of people on computers and or writing in notebooks or reading here. Very healthy, tasty food. Excellent coffee.

Bake Maine Pottery Café. 8 am 122 Washington Street. One of my neighborhood gems. Excellent place to work on computer or in notebook for an hour or so.

Yuri’s Desserts 8 am 3 Spring Street Korean pastries, airy donuts. Good amount of tables to sit at. Lots of people on computers or writing in notebooks.

Eighty-8 Donuts 8 am 225 Federal Street – a counter to sit at, but not a great place to settle into the white noise. But those donuts! Definitely (for me) just pick up a donut and go.

Now, if it’s raining – and I get into the car – it’s a whole other world out there from 5 am to 9 am.

June 6, 2025

Weekend Update: June 7-8, 2025

Next week at Maine Crime Writers there will be posts by Jule Selbo (Monday), Joe Souza (Tuesday), Vaughn Hardacker (Thursday), and Gabi Stiteler (Friday).

In the news department, here’s what’s happening with some of us who blog regularly at Maine Crime Writers:

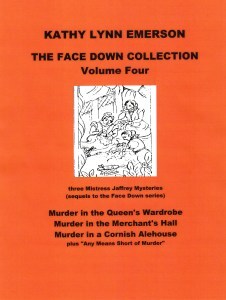

From Kathy Lynn Emerson: THE FACE DOWN COLLECTION FOUR is now available. This is an e-book omnibus edition of the three Mistress Jaffrey Mysteries, Murder in the Queen’s Wardrobe, Murder in the Merchant’s Hall, and Murder in a Cornish Alehouse. Each title is also available as a single-title e-book and in trade paperback.

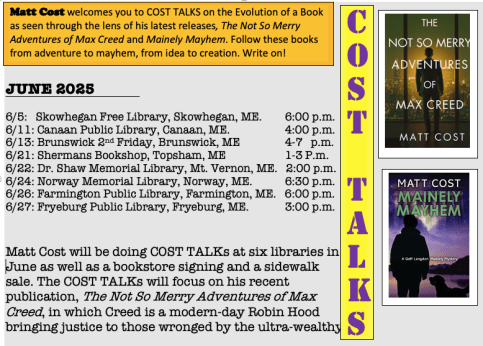

Matt Cost will be doing a series of COST TALKS in June as well as a sidewalk sale and a bookstore event. The dates, places, and times are below. If you are unable to make any of them live, a recording from the Baxter Memorial Library is available HERE.

An invitation to readers of this blog: Do you have news relating to Maine, Crime, or Writing? We’d love to hear from you. Just comment below to share.

And a reminder: If your library, school, or organization is looking for a speaker, we are often available to talk about the writing process, research, where we get our ideas, and other mysteries of the business, along with the very popular “Making a Mystery” with audience participation, and “Casting Call: How We Staff Our Mysteries.” We also do programs on Zoom. Contact Kate Flora

Another Country, Once My Own

John Clark musing about how one random thought can grow, and grow, hence this post. It all began, as many things these days do, in the heated pool at the Alfond Center in Waterville where I swim and and entertain the other swimmers most weekday mornings. In the midst of an exercise, I started thinking about Clabber Girl Baking Powder, and then what exactly did clabber mean. Here’s the definition: Clabber is raw milk that’s curdled. That got me thinking about other fictional personalities left behind by the ever-changing demands of advertising. Imagine, if you will, a dimension where they ended up after their promotional value waned. Herewith is an imagined day in Abandonedland.

It’s midmorning and Juan Valdez and Mrs. Olson are engaged in their weekly coffee contest, the loser being the one who makes a bathroom run first. Mrs. O has consumed seven cups of high octane brew to Juan’s five, but shows no sign of discomfort.

“Wasn’t it sad how the Clabber Girl, I can never remember her first name, had to rescue Betty Crocker after she went stir crazy at the baking competition last weekend,” said Juan.

The conversation was interrupted when a smirking Anthony Martignetti walked past, an arm around each of the Doublemint Twins. “Catch ya later,” He said, lust filling his voice. “We’re on our way to a hot meal, and I don’t mean spaghetti.”

Clara Peller was right behind them, pushing poor jaundiced Wolley Segap in his wheelchair while he mumbled and flipped through a tattered book like ones he’d proudly shilled in the old days. Clara, hands on hips, glared after Anthony, sneering, “That brat ain’t got near enough beef to keep those girls happy.”

Frank Bartles & Ed Jaymes, sat at the next table, whining about how they got no respect any more. “It’s like we’re the Rodney Dangerfield of the ad world these days, Ed said sadly, then brightened. “At least wine didn’t get hit as hard as whiskey did what with the on and off again tariff idiocy.

Buster Brown, who was sitting along with Josie The Plumber at the same table was also in a lamenting mood. “You think you have reason to complain, Nobody wants my shoes any more. It’s all fancy-ass things from designers with unpronounceable names like Laboutin, or sneakers with prices jacked into the stratosphere by punks pretending to be athletes. You never wouldda had real guys like Al Capone shilling footwear.”

“You think you got disrespected? Look at me,” groused Josie. “With all the extra bullshit and other crap being generated in Washington, not to mention in half the states, you would think I’d be in constant demand, but not a single call in years. Even worse, I’m stuck with a garage full of rusting tools.”

Just then a syrupy voice trilled from the gazebo. “Have any of you dear people seen Aunt Jemima?” trilled Mrs Butterworth. “We’re supposed to meet Mary Kay at lunch so we can try out her new pancake make-up.”

“No,” said Frank Bartles, “but I swear I saw Mr. Whipple put the squeeze on Sarah Tucker over at the inn last night. It shook up poor Uncle Ben something awful, being as how he has had such a crush on her all these years.

“Remember when Mr. Clean ran for mayor, promising he’d bring back morality? Guess his white tornado wimped out pretty quickly,” lamented Ronald McDonald. “I would have thought when Little Debbie was caught in bed with Mikey, folks would have been more upset, but all I heard from folks was ‘that’s Life.’ And if that wasn’t bad enough, the Morton girl was kicked out of high school last week for refusing to stop using salty language. I sure wish we could go back to the old days. I never did get to see the USA in a Chevrolet.”

Aunt Bluebell wandered through the crowd, handing out paper towels, particularly to those who had just come from the funeral. “Poor Marlboro Man,” sniffled the bellhop while puffing on a Phillip Morris cigarette, “Life just won’t be the same, and he didn’t even get to ride off into the sunset since the cemetery was in the other direction.”

June 4, 2025

Springtime Adventures

We returned three weeks ago from a two-week holiday, mostly in Scotland with a couple of bonus days in Ireland. As my head continues to whirl with memories and images of our travels, I’ll take this opportunity share them with MCW readers, especially those who enjoy a wee armchair adventure when friends post photos of their trips. (“Wee.” I picked up that expression somewhere between Edinburgh and the Isle of Skye.) Settle in with a cuppa and cross the sea with me.

We spent time in Edinburgh at both the beginning and the end of our trip. It’s a beautiful city, easily walkable and full of history and stories. We enjoyed both the medieval Old Town and the New Town full of Georgian buildings.

We had to hunt for it, but found the Writer’s Museum tucked down a cobblestone close off the Royal Mile. Robert Burns, Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson are particularly well-celebrated. I was hoping for some mention of Val McDermid or Ian Rankin, but did not find them, though we didn’t have time to check out every nook and cranny of this historic building.

We took a three-day trip into the Highlands and to the Isle of Skye, the charming town of Portree being our base for exploration. The scenery was stunning, start to finish. Below are photos taken on the drive through the Highlands to Skye and on the island itself.

Glen Coe

Bluebells fill the woodlands in spring. Some botanists call them wild hyacinths.

Wisdom posted in a shop near Glen Coe.

The path down to the Fairy Pools on the northern slopes of the Black Cuillin mountain range on Skye. The hike down and back was a vigorous way to start the day.

On our way back from Skye we stopped at a seaside spot and took this selfie. Contrary to our expectations, we enjoyed bright sunshine at least part of almost every day. And plenty of wind, too.

After leaving the Highlands we visited our friend Robin Facer Taylor in Stirling, where she lives with her family when they’re not at their summer home in Maine.

Robin, wearing a tartan jacket for the occasion.

Crime Bake folks will remember Robin, and her amazing video production skills. She’s also a terrific writer and a marvelous tour guide. Stirling is less than an hour’s drive from Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park, and Robin knew the most beautiful roads to get there.

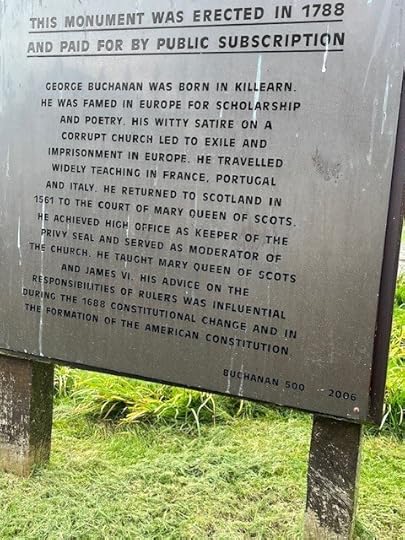

Though my last name is Scottish, my father’s family has been in this country for many generations, so I didn’t grow up steeped in Scottish lore and culture. But a bit of research revealed the Buchanan Clan was based around Loch Lomond. It turned out that area, particularly the village of Killearn, is Buchanan Central.

This monument in the center of Killearn commemorates the life of George Buchanan (1506-1582) who turns out to be quite an amazing possible ancestor.

Here’s a thumbnail of George’s accomplishments. The plaudits, not to mention the size of that monument, attest to his remarkable attributes.

Quite the resume, no? I thought it particularly interesting that his work influenced the framers of the US Constitution.

Many, many Buchanans are buried in this Killearn graveyard. If I ever write a book with a Scottish theme, this will have to be the cover art.

The Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow.

We spent three days in Glasgow after bidding farewell to Robin and her lovely husband and sons. We had some fine meals there (if you ever find yourself in Glasgow, be sure to go to Cafe Gandolfi) and loved our time at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

We returned by train to Edinburgh to wander that lovely city for a few more days, then we were off to Dublin.

Longtime readers of this blog know that my mother’s side of the family is Irish, and I was raised step dancing to the the music of that beautiful country. If you missed the step dancing post, it’s here:https://mainecrimewriters.com/2016/03/15/my-dance-of-fame/

We’ve visited Ireland several times, and while we only had two days this time, we were able to meet another cousin who lives outside of Dublin. My cousin Gráinne told me her uncle Mícheál Ó Fiannachta is the family Seanchaí —the historian and keeper of the stories. She was right. We talked for two and a half wonderful hours about ancestors and loved ones.

Our lunch meeting was at Davy Byrnes, a Duke Street pub mentioned in James Joyce’s Ulysses. The Gorgonzola sandwich on brown bread eaten by Leopold Bloom in the book is still on the menu every day. How’s that for tradition?

Micheal and me, on a sunny day in Dublin last month.

Our final stop before heading home was the Cobblestone, a Dublin pub known for its traditional music.

Our friend Simone, a talented fiddler, once again was part of the Thursday evening session. The music had us tapping our toes to tunes familiar and new, a perfect ending to a terrific trip.

Did you travel this year? In Maine or outside of Maine? In the US or elsewhere? Please share your tales in the comments.

Brenda Buchanan sets her novels in and around Portland. Her three-book Joe Gale series features a contemporary newspaper reporter with old-school style who covers the courts and crime beat at the fictional Portland Daily Chronicle. Brenda’s short story, “Means, Motive, and Opportunity,” was in the anthology Bloodroot: Best New England Crime Stories 2021 and received an honorable mention in Best American Mystery and Suspense 2022. Her story Assumptions Can Get You Killed appears in Wolfsbane: Best New England Crime Stories 2023.

June 3, 2025

Can You Afford to Get Published?

I wrote this post a decade ago. I’ve given it some tweaks, but it is still true. Probably more true now than ever. Unless you’re an A-List author, the burden of marketing mostly falls on you, and it is expensive. Fun, too, of course. Who doesn’t love meeting readers or getting new ones? But while most of us put a shiny face on things, the truth is that the business side of writing is a challenging one, even though it goes with the territory.

Kate Flora here, with a question I’ve been pondering on again this week. Usually, published writers like to paint a glowy picture of the world we inhabit. It is true that having struggled, often for years, to finally become published, we are grateful for the chance to get our work out there and have it read, and I beam with pride when I look at my row of published books. But when I do the taxes, after putting together the figures for the past twelve months, I estimate that I’m working for about a dollar a day. I thought it might be interesting to readers to have some insight into the published author’s reality.

Kate Flora here, with a question I’ve been pondering on again this week. Usually, published writers like to paint a glowy picture of the world we inhabit. It is true that having struggled, often for years, to finally become published, we are grateful for the chance to get our work out there and have it read, and I beam with pride when I look at my row of published books. But when I do the taxes, after putting together the figures for the past twelve months, I estimate that I’m working for about a dollar a day. I thought it might be interesting to readers to have some insight into the published author’s reality.

I published my first mystery, Chosen for Death, back in 1994. For those early books in my Thea Kozak series, the advances ran around $5-6,000, and I usually earned royalties on top of that. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the way publishing works, when a publisher buys a book, they usually give the writer an advance of some amount that will be offset against the amount of money the work ultimately earns. Often this is divided with some money due on signing the contract, and another part due when the book is actually published, which may be a year or more down the road.

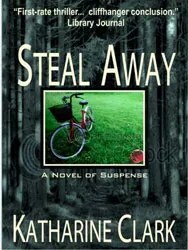

I puttered along with my advances in this range until I sold my breakthrough book, Steal Away, (published as Katharine Clark) which had a big advance, was a book club selection, and was sold as an audio book. The book did not earn back that big advance and so, since publishers considering buying a book look at sales numbers, my happy midlist career was ruined.

I puttered along with my advances in this range until I sold my breakthrough book, Steal Away, (published as Katharine Clark) which had a big advance, was a book club selection, and was sold as an audio book. The book did not earn back that big advance and so, since publishers considering buying a book look at sales numbers, my happy midlist career was ruined.

But I am stubborn, so I kept on writing, and eventually sold my Joe Burgess series. Some time had passed and the advances had gotten smaller. Then I sold my first true crime, Finding Amy, to a university press. Another small advance that I shared with co-writer, Joe Loughlin.

And so it has gone. Selling something that has taken a year or five or twelve to write for a few thousand dollars does not seem like a sensible economic model. With smaller publishers, there may not even be an advance. In those cases, we publish on faith (faith on both sides) and hope for a return.

One year, I had two books published, my second true crime, Death Dealer: How Cops and Cadaver Dogs Brought a Killer to Justice, which I had worked on for five years, and the fourth Joe Burgess. The advances, combined, didn’t add up to the $6,000 I used to receive.

There are a lot of expenses involved in promoting a book. Many readers (and even writers aspiring to be published) don’t realize how many expenses are not covered by the publisher. For example: designing and maintaining a website, designing and printing publicity materials like flyers and bookmarks, buying copies of the book to give to people who’d helped during the writing process, buying copies of galleys to mail out for reviews, and postage for mailing. Then I have to buy copies of the books I hope to sell at book events, along with the expenses of the thousands of miles I put on my car. Also, of course, table covers, posters, book display racks, a folding table, and a handy little cart to tote is all to the venue.

And that’s not all. I was lucky enough to have Death Dealer be named an Agatha finalist, so I attended the Malice Domestic conference in Bethesda that June. Don’t get me wrong, conferences are wonderful places to network, hang with friends, get ideas, and be comforted in the presence of others who also hear voices in their heads. But, with airfare, hotels, and registration, a conference can easily cost a thousand dollars.

Twice, hoping for a breakthrough, I took a chance on hiring a publicist to see if I could break out and get my books greater recognition. Neither time did that work out. Thirty years in, I am still awaiting my breakthrough book.

Even when a book earns royalties, publisher routinely pay them only once or twice a year, and usually several months after the money has been earned, and traditionally hold back part of those earnings “against returns.” Most recently, a publisher sent me a royalty statement but hasn’t sent the check.

If an author is going the Indy model, or self-publishing, there are even more expenses. Formatting the print and ebooks unless you can do that yourself, getting a cover designed, maybe choosing to buy your own ISBNs.

So here I sit, thirty years in, twenty-seven books in print and another, Those Who Choose Evil, due out this month. I have some wonderful successes along the way. The writing community has been generous. Death Dealer was an Agatha and Anthony finalist, and won the Public Safety Writers Association 2015 award for nonfiction. And Grant You Peace won the 2015 Maine Literary Award for Crime Fiction. I am humbled at the recognition and deeply grateful to my peers. I’ve received a lifetime achievement award from the Crime Bake and the Lea Wait Award from the Maine Crime Wave.

So here I sit, thirty years in, twenty-seven books in print and another, Those Who Choose Evil, due out this month. I have some wonderful successes along the way. The writing community has been generous. Death Dealer was an Agatha and Anthony finalist, and won the Public Safety Writers Association 2015 award for nonfiction. And Grant You Peace won the 2015 Maine Literary Award for Crime Fiction. I am humbled at the recognition and deeply grateful to my peers. I’ve received a lifetime achievement award from the Crime Bake and the Lea Wait Award from the Maine Crime Wave.

Logically speaking, I am deeply in the hole, though I am lucky enough to have my backlist available as e-books, which brings in some income. I need to make my books into audio books, which is another process to learn and one that takes time. I’m not entirely joking when I ask if someone would please send me a young person who can take care of Instagram and TikToc and all manner of marketing I never get to.

Obviously, I am not going to stop writing, and neither should you. But you should be warned: despite the honor of the thing, unless you have a best-seller, it is hard to make a living at this. That’s why we speak and teach and do manuscript reviews and a zillion other things and why we tell aspiring writers: don’t quit your day job, or be lucky enough to have a partner with benefits.

June 1, 2025

But What Were They DOING?

Kaitlyn Dunnett/Kathy Lynn Emerson here, today thinking about a problem I always encountered between my rough drafts and my finished manuscripts.

Kaitlyn Dunnett/Kathy Lynn Emerson here, today thinking about a problem I always encountered between my rough drafts and my finished manuscripts.

My earliest versions of many scenes were often straight dialogue—I put my characters on the page and let them talk to each other. When I revised, I’d add descriptive details to flesh out both the characters’ appearance and their surroundings. How much or how little of a character’s physical description I included depended on whose point of view the scene was written in. So did the specifics. Let’s face it, a woman’s comments or thoughts about her own looks are likely to be significantly different from the way a man describes her, and his description would vary depending on how he felt about her.

I also had to think about character’s reactions, which don’t always come across in straight dialogue. Reactions can be expressed in thoughts (for the POV character), actions, and what I’ll group for simplicity under the heading of dialogue tags. While “said” is generally considered to be an invisible tag, inserted to identify the speaker but not distract from the flow of the dialogue, it can also be overused, especially if it is followed by that same character’s action. These days I much prefer to change something like “I’ll go,” he said, and headed for the door. to “I’ll go.” He headed for the door.

I also had to think about character’s reactions, which don’t always come across in straight dialogue. Reactions can be expressed in thoughts (for the POV character), actions, and what I’ll group for simplicity under the heading of dialogue tags. While “said” is generally considered to be an invisible tag, inserted to identify the speaker but not distract from the flow of the dialogue, it can also be overused, especially if it is followed by that same character’s action. These days I much prefer to change something like “I’ll go,” he said, and headed for the door. to “I’ll go.” He headed for the door.

If overuse of said can get annoying, what’s worse is having a character smile, grin, laugh, or sigh repeatedly. Of course they can do those things, but not without a good reason. Moreover the reader needs to understand why a character reacts that way. I’ve come to prefer having characters wring their hands, shrug their shoulders, flex a sore muscle, or waggle a nervous foot, just to mention a few non-facial reactions. Of course, any of those can be overused too.

If overuse of said can get annoying, what’s worse is having a character smile, grin, laugh, or sigh repeatedly. Of course they can do those things, but not without a good reason. Moreover the reader needs to understand why a character reacts that way. I’ve come to prefer having characters wring their hands, shrug their shoulders, flex a sore muscle, or waggle a nervous foot, just to mention a few non-facial reactions. Of course, any of those can be overused too.

“Just give them something to do.” is generally good advice, as long as the reader knows why the character is doing it. The preparation and consumption of food and drink are useful actions. So are interactions with animals. But again, either can be overdone. A character reacting to that first life-giving sip of coffee in the morning is a bit clichéd but useful . . . as long as you don’t go overboard and mention every instance throughout the novel. As for pets, there are many mystery series that include cats and dogs, and there’s nothing wrong with including their interactions with their owners, but readers don’t really need to know (true example from a popular cozy series) every time the cat uses the litter box.

Giving too much detail while someone performs an everyday task is not just unnecessary, it’s distracting. Unless, of course, you are planting a clue or revealing a character trait. If a character is making toast, there’s no need to describe it step by step. Readers already know how to use a toaster. Are there exceptions? Sure. In the film Kate and Leopold, the way time-traveler Leopold tries to “fix” a toaster not only establishes his character but also advances his relationship with Kate.

What about you, dear readers? Any good (or bad) examples of descriptive details you’d like to share?

Kathy Lynn Emerson/Kaitlyn Dunnett has had sixty-four books traditionally published and has self published others. She won the Agatha Award and was an Anthony and Macavity finalist for best mystery nonfiction of 2008 for How to Write Killer Historical Mysteries and was an Agatha Award finalist in 2015 in the best mystery short story category. In 2023 she won the Lea Wait Award for “excellence and achievement” from the Maine Writers and Publishers Alliance. She was the Malice Domestic Guest of Honor in 2014. She is currently working on creating new editions of her backlist titles. Her website is www.KathyLynnEmerson.com.

Lea Wait's Blog

- Lea Wait's profile

- 507 followers