Michael Jecks's Blog, page 3

April 2, 2022

REVIEW: A DEVON NIGHT’S DEATH by Stephanie Austin, published by Allison and Busby

ISBN: 978 0 7490 2892 3

This is one of those books that arrived without my expecting it.

Usually, books I don’t expect have one thing in common – they aren’t the sort of books I’d ever think of buying. I am, after all, a crime writer.

There is a strange thing about publicists in publishing. There appears to be a belief that anyone who has ever read anything will automatically love whatever it is that they have. They throw books at reviewers with gay abandon, flinging rose petals in the path of their authors, no doubt, while letting them know that their wonderful purple prose will soon receive a heartfelt accolade from another author. Thus it is that I received LOVE IN COLOUR, which is a series of reimagined mythical tales from around the world, as the cover proudly declares – or as Candice Carty-Williams says “So rarely is love expressed this richly, this vividly…”

Why the hell send that to me? Is there a crime of any sort, let alone a murder?

However, every now and again there is something that is actually suitable. I’ve recently reviewed KJ Maitlands TRAITOR IN THE ICE (which is superb), and I have two superb books by the brilliant Tony King to finish, plus a Erin Young’s first foray into crime to occupy me. And then I have twenty three titles from publishers, plus two books about Russia and Putin’s kleptocracy to read (PUTIN’S PEOPLE by Catherine Belton and KLEPTOPIA by Tom Burgis), and HOW TO STAY SMART IN A SMART WORLD by Gerd Gigerenzer, which I’m really looking forward to, and THE ANGLO-SAXONS by Marc Morris, which has been waiting far too long to be reviewed.

Which is a long way of saying, that I really appreciate these books that are suitable for me as a reviewer.

Why did I receive A DEVON NIGHT’S DEATH? Well, because it has several aspects that a sensible editor and publicist thought made me a suitable reviewer. You see, someone here thought about things. How did they think? First, they thought about asking the author who she thought would be a suitable reviewer – and she thought of me (thanks, Stephanie). I don’t know Stephanie – I have never met her to my knowledge, but I will do before long.

What else made it a book for me to read? The fact that it’s set in Devon. That helps. I live here, after all. And yes, it’s a book involving death – which is meat and potatoes to me (except it’s not, because I’ve had to curtail the spuds since my diagnosis of diabetes earlier this year, dammit).

So, having already bored you with four hundred and fifty words, what is the book about?

The main character is a reluctant antique shop owner and accidental amateur sleuth called Juno Browne (don’t forget the “e”). She has an antique shop in Ashburton (I like Ashburton – an old Stannary town on Dartmoor which still has a school building created by Bishop Stapeldon in the early 1300s), but she has a problem. It is not a great money-maker, and she has spare rooms to rent out. When one day a mild and gentlemanly book binder and paper-marbler (would that be the correct term?) offers to rent the room so he can free up space in his house, she’s delighted. He is an interesting character, and she develops a keen interest in him when she learns that he was the victim of a hit and run attack the previous year, although why a mild and inoffensive book dealer should be attacked … well, it doesn’t seem likely.

And then one evening Juno accidentally disturbs intruders on her boyfriend’s land, and although no one is hurt, only a very short while later she learns that one of the intruders died, falling to his death from the old viaduct over Tavistock. She has to wonder whether that was accidental or suicide – or possibly murder? And then there are more break-ins and a grisly murder, all mingled with gambling, alcoholism and drugs.

I never knew Ashburton could be this exciting!

This is the sixth (I think) in this series, and I found it brilliant. It is not a modern style of glitzy murder story – by which I mean there are not ludicrous scenes of gross and unnecessary violence. This is much more of a slightly hard-edged cosy crime novel. Think Miss Marple with a little more of an edge.

The locations are ideal. The town of Ashburton is a little larger than Mary Mead, but that adds to the cast of characters, and since it’s a small town still, and set in the middle of rolling countryside, there is no distraction as you’d find in a large city. It feels cosy, and the writing suits the town perfectly.

I have mentioned characters – Stephanie has developed a superb cast in this story. There are Ricky and Morris, the gay couple who work in the theatre, and who are trying to put on a play with the “help” of a London director, Gabriel. All are brilliantly portrayed, as are Juno’s friends in her shop, Sophie and Pat. In fact all the characters are wonderfully set down on paper – in a few pages I felt completely involved with all of them, and knew each individually.

Stephanie has a story here that is superb – the plot is excellent, with some twists I hadn’t expected, with a basic theme which was entirely new to me, with a criminal endeavour that had me grinning with delight. In short, it was superb, and a very bad distraction from my editor’s notes, which I was supposed to be working on.

So, this one gets a big thumbs-up from me. Highly recommended for those who enjoy cosy crime, who like Devon and Dartmoor, and who want a satisfying tale without the violence of Cathy Reichs or Patricia Cornwell. This is a story that depends only on good writing and brilliant characters and plot – and it works!

March 31, 2022

Review: TRAITOR IN THE ICE by KJ Maitland, published by Headline Review

ISBN: 978 147 227 5479

There are times when you pick up a book and just know you’re in the hands of a brilliant story-teller.

Karen Maitland is an old friend, but don’t let that get in the way of things. She has been a writer of superb stories for some years, first of all with her brilliant medieval thriller (it’s hard to know how else to describe it), THE COMPANY OF LIARS, in which she mingled suspicion, superstition, and a degree of horror to weave a thoroughly compelling story. Since then she has brought out a series of books, each of them inventive, full of characters that leap off the page, and plots that … well, that make the reader shiver.

I was on a panel with her once, and answering questions at the end of the gig, she was asked why she didn’t write a series. Her answer was deliciously frank: “I tend to kill off all my characters, so you see it would be difficult.”

However, she has suddenly had a conversion. After trying to persuade her for some fifteen years that she really ought to think about writing a crime series, she has finally succumbed.

TRAITOR IN THE ICE is the second in her series starring the ill-fated Daniel Pursglove – the first being THE DROWNED CITY, which I wrote about last year.

Pursglove is her investigator. He has been a felon, has used many names, and now he is at the mercy of Charles FitzAlan, spymaster to King James 1. If Pursglove does not help FitzAlan, he will be returned to gaol, where he can expect a brief incarceration.

This is all set in the winter of 1607, a dreadful time with appalling cold. The kingdom is in a state of fear, with the population dreading a Catholic attack. It’s only a short while after the Gunpowder Plot, and it’s suspected that one of the prime movers behind that scheme was a notorious traitor, Spero Pettingar. FitzAlan suspects that the man might be hiding in Sussex, in Battle Abbey, protected by the Catholic household of Lady Magdalen Montague. Already one spy sent to watch the house, Benet, has been discovered dead.

He is to be only the first person murdered.

But it’s not just the killings. Maitland brings to life all the most primitive superstitions and fears of a population on the brink of disaster. This is a time when people could easily die of the cold, when the Thames froze over, when a walk from your door could lead to your succumbing to the weather. It was a terrifying time for the peasants who endured it.

Yet if you lived in the “big house”, you may have to work your fingers to the bone, but it was likely that you would survive. There were fires, there was food, and while the house might be run by a despot, at least life was easier. Unless you were Catholic and trying to keep the world out, protecting priests of the banned religion.

And if you were a spy, like Purseglove, every day was fraught with danger.

This is one of those books that grabs your attention from the first. It grips, and sucks you in, willingly or not. Maitland has managed a marvellous array of characters, and shepherded them to her will. She her cast of characters to life as vividly as a film. She has an amazing talent for details and glimpses of how people used to live; not just the rich and famous, but the poorest too.

I cannot recommend this book highly enough. A storming, fabulous masterpiece from a writer at the very top of her game!

Highly recommended – a brilliant read!

March 29, 2022

Review: SHADOW SLEEPER by Madalyn Morgan

Just recently I have had a few historical books to read – but not books which are necessarily set a long way in the past. Tim Glister’s A LOYAL TRAITOR, for example, set in the 60s – and I’m shortly to review a quartet of some of my favourite spy stories, the LIQUIDATOR books by John Gardner, also set in the 60s. But this book is a different one.

First, a brief disclosure – I know Madalyn. But then again, in a career of nearly thirty years writing, I have got to know just about all crime writers in the UK and US, as well as quite a few elsewhere in the world, so that isn’t much of a disclosure. Have I known her a long time, no. Have I been granted access to her books over years? No. This book came as a surprise to me. And a very welcome one.

This is the second in Madalyn’s Dudley Green Investigations series. I haven’t read the first in the series, but that doesn’t detract from this book – it works very well as a stand-alone title.

The concept behind the series is quite simple. Ena Green and her business partner Artie Mallory ran a small detection agency. She had spent the last few years as a cold cases officer, until she got fed up with it. “She hated the lies, the dirty tricks, spies and traitors – and having to continually sweep the office for listening devices.”

This story begins with a bang, with an attack on her in her offices. She is knocked down and severely shocked, but not badly injured. More of a concern to her is the loss of a series of files on a current case she is working on.

Rupert Highsmith, a friend, had a chequered past. He had worked in counter-espionage, and some suspected he might have been a double agent. However he had been one of the few men before the War who had been instrumental in bringing about Hitler’s downfall. He had enemies, many of them within the security services, because he was known to be homosexual, and that itself could result in a man’s arrest and end his career.

The file contained photos of a suspicious – or incriminating – nature; photos that seemed to allege that Highsmith had seduced a young boy in a hotel in Berlin.

That is the beginning, and the story moves on at some pace, but although this is a crime story, with murder and skullduggery galore, the main reason why I absolutely loved it was because of Madalyn’s command of the period. When she talks about the Zephyr and Sunbeam cars, I can see them. They were the cars I saw when I was a youngster. I remember those greyish days, and this book brings it all back to life with wonderful familiarity.

There are many books written about this period, but there are very few books written today which can bring it to life in the way that Madalyn has.

All of which means this is a highly recommended title, and well worth the investment!

February 9, 2022

Review: A LOYAL TRAITOR by Tim Glister, published by Point Blank on February 10th

ISBN 978 0 86154 166 9

Since I’m a child of the 60s, I’ve always been interested in books of the period. I love Graham Greene, Ian Fleming, John le Carré, John Gardner … all inspired me with my own writing, and they’re writing about a period I know well.

It’s not just spy and crime stories – it’s the cars, the whiff of cigarette or panetella smoke, the smell of grotty aftershave, the holes in London where buildings stood twenty years before, the jagged, broken ruins where incendiaries blow-torched whole streets, and which no one had got round to rebuilding yet. I still remember one of the last big craters being developed into a big BT building just north of St Paul’s when I was going to university in the late ’70s. The War was still very fresh in the mind of the city.

So it was very pleasing to receive A LOYAL TRAITOR, and it started well. I liked the characterisation of the main players, and the use of locations. It begins with a particularly nasty murder – an entire family wiped out by an assassin, but then moves quickly on to Richard Knox in Vancouver Island, on a mission to speak to a man suspected of flying Soviet spies into the USA from Canada, then to Banica in the Dominican Republic, where Abey Bennett, a CIA agent, is unhappy about a prisoner swap.

There is the atmosphere of spies and counter espionage, of plots and counterplots that circle agents constantly. Knox is fed up with it, especially since he’s lost his best friend, Williams, who was presumed killed when on his last mission – a mission on which Knox had sent him. Guilt constantly tears at him for that. I think Abey is also well depicted. This was a time in the CIA when women, as in most of society, were not given the same prospects as their male counterparts. As spies, they were respected, but misogyny hampered their careers, and I think that is very well depicted here.

So, what is the story? The main theme is the sudden appearance of a man who describes himself as a Russian assassin – but it is soon discovered that he is Williams, Knox’s friend. He is in a terrible state, his mind damaged after some kind of brainwashing. But he has flashes of memory, and he is terrified that he might do something, or be responsible for something, that will change the balance of power in the Cold War.

Knox is loyal to his friend, but he is anxious about the way Williams will be treated by an unsympathetic intelligence service.

As a story, I found this quite engaging. It has a brilliantly convoluted plot with layer on layer of subplot at every turn. The themes were very well put down, and the writing is very strong. It works really well as a thriller.

There were aspects that didn’t work for me, I have to admit. It reads like a story that has been well-researched, but it also feels like a story in which twenty-first century sentiments have been grafted onto the 1960s. There were some themes which grated: Knox’s guilt about Williams’ capture by the Russians became repetitive, for example. However, this was a really good distraction from my own work – and enjoyable.

So, if you want a good distraction from your work, and are prepared to sink back into a version of the 1960s, this could be just the book for you.

January 28, 2022

Review: MAN ON FIRE by Humphrey Hawksley, published by Severn House

ISBN: 978 0 7278 9034 4

There are some names which are immediately recognisable. When I hear certain names announced on the radio or on my computer, they instantly bring to mind something that makes me stop for a moment. Humphrey Hawksley is one such name.

I seem to have known Hawksley for decades. As a BBC reporter, he has been all over the world bringing stories alive to his audience, often in trouble spots, often in danger, often with members of the military and politicians. It is a world he knows very well indeed.

Some years ago, apparently, he started writing novels as well. This is his latest, and he brings all his experience to bear.

MAN ON FIRE brings back his hero Major Rake Ozenna, a native of Alaska who has joined the US Army and become a special forces operative. This book starts with Rake and his friend from childhood, Mikki Wekstatt, are out beyond Little Diomede, a small island in the Bering Strait that separates the USA from Russia. They are in a fishing dinghy, waiting for a contact to make their way to them from Big Diomede – a larger island over the border in Russian waters.

It’s fair to say that the book starts with a bang. The contact is making her way to them, when she is caught in a Russian spotlight and shot at. After an intense fight, Rake and Mikki manage to bring her to their vessel and hurry back to the shore, but she has been too badly injured in the firefight at sea, and cannot give them the information she as bringing.

However, Rake’s boss, Lucas, knew that she had been bringing over a USB drive with details of a new weapon which the Russians were threatening to use. But without the drive, Lucas and the intelligence community were blind. They didn’t know what the weapon was, nor how to prevent its use.

They must learn more. To do that, Rake must embark on his most dangerous adventure yet.

This is a book written by a brilliant thriller author. The great thing about a book by Humphrey Hawksley is, you know he has the in-depth knowledge. He knows the countries he describes, he understands the politics, he has travelled the same roads. It all adds up to a compelling, believable plot that is utterly convincing.

And so, of course, it is highly recommended!

January 15, 2022

Review: BOXING CLEVER by Andy Costello

There are few sporting stories that combine the achievement of so much, followed by utter collapse, as that of Andy Costello.

I first met Andy some six or more years ago. He had called and asked me if we could get together over a coffee to talk about his life story. It sounded interesting, and I agreed to see him.

Andy was a tall, very wiry man with a calm, gentle aura. I knew he had been a serious fighter, that he had been in trouble with the police, and had spent a few years in prison. I confess, I was slightly nervous. After all, turning down someone who has a career as a cage-fighter could lead to my seeing a more aggressive side to him.

However, he remained polite and thoroughly professional at all times. I found myself warming to him.

He led me through his life story. There were no apologies, only a self-effacing embarrassment on occasion. I took copious notes, and at some point I decided I really wanted to work with him on his memoirs. It should be really interesting. When I got home I set out the synopsis for a book, sent a copy to him, and when he approved it, I sent it to my agent.

And that was where things went wrong, sadly. My agent was happy enough, but every editor she spoke to said that they had too many ex-police memoirs on their books already. Although she tried to explain that this was a totally different story, they wouldn’t listen (editors are like that) and regretfully my agent decided she was flogging a dead horse. I couldn’t work on it without an advance of some sort – my finances were in their usual dire state at that time – and so the project lapsed. I had to apologise profusely to Andy, and tried to support him. I did say that if he continued with it as a project, I’d be delighted to read through his manuscript and offer any advice I could.

About eighteen months ago, he wrote to me to say that he had written and published his book, and would I like to see a copy. I read it, and it blew me away. It was brilliant.

So, who is this Andy Costello?

A chess champion in his early teens, Andy learned Judo to overcome his weight problems. He went on to become one of the country’s top martial artists when he was seventeen, representing his country and becoming six times the UK champion.

Good education and an exemplary record helped him join the police. For a solid, well-brought up middle class lad, it seemed a good idea. His life was moving upwards at speed.

But rarely has a man with such promise fallen so far.

In the police there was a strong drinking culture, as was common for jobs with very high stress and a certain amount of danger. However, for Andy the strain was much worse. Because of his position with the GB Judo squad and his success in Police Judo circles, whenever there was a dangerous situation, a domestic fracas, a robbery, or a drugged-up teenager with a knife, the police invariably called on their resident martial artist.

His success with early scenes of violence led to his being called up more and more regularly. He was the expert in Exeter, the one officer who could be relief upon to stop violence without needing a firearm. And that reputation, the constant stream of highly dangerous circumstances in which he found himself, and the police culture of heavy drinking, all took their toll.

In 1999, Andy was found to be drunk in charge of a police car, and his life came to a halt.

In short order, he lost everything: his job was gone, and he knew no other. The camaraderie that was so much a part of his life went with it. But worst of all, with it went his self-respect. He was forced to take jobs as a doorman, setting up his own company, and kept the wolf from the door.

This is a story of three parts: an ordinary childhood showing extraordinary promise, followed by what appeared to be success with a career in a professional police force.

The tragedy for Andy was that the police did not help or support him when it became obvious that Andy was going off the rails. The lost of his prestige and self-respect as he lost his job, and the continued drinking as he slipped further into alcoholism concludes with the return to competitive success.

Although this book could appear to be more of a misery memoir than a sporting success, it will work for many readers. Andy is a very competent speaker and this book will be motivational. It will show how even after the worst of disasters, determination and drive can push a man to great heights and renewed success.

The book will appeal to fans of martial arts, cage fighting and chess boxing, yes, but it will also appeal to many because Andy is a positive role model. With the focus on police culture and the treatment of battle-scarred and traumatised officers, this book will appeal to a much broader audience.

It is a brilliant story, told extremely well by a guy who has been let down enormously badly over the years. It’s a seriously good read, by turns funny and terribly sad.

Highly recommended – one of my favourite books about the police and policing.

January 14, 2022

Review: BLACK BRICK by Jack Spittler

Many times over the years I have been asked to read over someone’s book. Usually it is a friend. Invariably it is a nervous character who sidles up with an easy to recognise expression of anxious anticipation.

They have the twin fears: first that I will say I cannot make time to read their work. This is a fixed position, because it is damned hard to make time. It’s hard enough to read the books I really want to, without taking on review copies of books I don’t know whether I’ll like or not. And reviewing for friends or others means eating into my spare time. During my working hours (which are considerably longer than most working weeks) I have to try to earn income. Reading for other people, unpaid, doesn’t fit that criterion.

Sometimes I’m sent books to review from publishers. That doesn’t help. Recently I have been sent a number of bodice-rippers, a book of short stories on the subject of “love” (WHY?), the life story of a Harry Potter actress and the memoirs of a Radio One DJ. Do I look like the sort of crime writer who would want to read such stuff? And if I were, my readership tends to be people with interests in murder and medievalism. Who would want to read my review of a love story?

I have no interest in any of these. OK?

However, each story donor also has a second terror. That is, that I’ll say “yes”.

Why would they fear a positive response? Because I will be honest. If I’m reading a book, whether it’s for review or to give advice, I think the author deserves an honest assessment from me. Any author giving me his or her work will receive a genuine critique – and that itself is a scary proposition.

I know all about such fears. After all, in the last 25 years I must have submitted about fifty novels to friends and family, agents, editors and other authors for them to comment on. It is not a pleasant experience. There is always that long, deeply painful period of waiting, hoping that the reader will be gripped, thrilled, and delighted.

So you will understand that, much though I love reading, and really enjoy receiving new books to read, when it’s a book from an unpublished friend, there is a truly daunting aspect to it. It could easily lose many good friends. But I won’t lie to them. Which is why you see few, if any, comments here about books by friends who are not published. The few friends I do speak of are either professional writers (Karen Maitland, Susanna Gregory, Quintin Jardine, and many more) or have been let down badly, I believe, by the publishing industry (go and look up Andy Costello’s brilliant BOXING CLEVER).

Some eight years ago, I was privileged to be invited to go to New Orleans. A fan of my books, Jack Spittler, had asked me to be his guest at the annual New Orleans Mardi Gras. To my astonishment, this meant I was the Grand Marshal of the first parade of 2014 (if memory serves). It was a wonderful time, and Jack and the other organisers could not have been more kind and generous. It left me with memories I’ll hold for the rest of my life.

Which is why, when I recently received in the post a book by Jack Spittler, I was aware of a certain trepidation. I really like Jack and his family, and I did not want to have to rip it to shreds. As soon as I could, I sat down to read his work.

It is a crime book. That immediately sets it high above most of the books I have received from publishers in the last quarter.

However, it is considerably better than many crime books I’ve been sent. I loved it.

First, it is set in an area I really don’t know at all: Oklahoma. The countryside, the people, were all brought home vividly to me. Why? Because it is like Scandinavian stories, or like Michael Connelly’s stories set in Los Angeles, or like James Clavell’s books – they were set in locations I do not know and the comparison with my world makes such stories stand out. The difference in culture between those areas and my own give the stories additional depth. That was the case with Jack’s book too.

This story, THE BLACK BRICK, has the additional strength of a cast of wonderfully realised characters. Again, these were new to me because it is set in Native American territory, and with Native American protagonists. For me, that brought a whole new dimension to the writing.

The Black Brick starts with a violent sailor, Lonnie, who is forced to leave the US Navy after he killed who fellow sailors. It is clear that he was provoked, but that is not enough to excuse his violence and he is convicted of murder.

However, on his journey to the prison, he escapes and eludes his guards, only to be found and befriended by a gang which wants him to join them.

Meanwhile Jay Nation is a cop, raised on the reservation, and enjoying his job. There is rarely any violence or trouble, and with his position confirmed by the State, he feels up to any challenge – until, that is, there is a murder, and rumours of a “Murder Incorporated” organisation based in Texas which is killing within Jay’s territory. The first victim is the patron of a local bar 0- but it sounds wrong to Jay. The man is only an ordinary guy, not the sort to justify a contract killing. But as Jay delves deeper into the background, he begins to uncover secrets that should have stayed hidden.

He’s fortunate in his colleagues, but soon the FBI get involved, and he has to contend with Britt, a prickly, abrasive woman of Sak and Fox tribe. She is not going to make his life any easier.

This is a brilliant first outing for Jack Spittler, and a great introduction to Jay Nation. Each chapter has its own introduction which incorporates a piece of Native American wisdom. For example, Chapter Six has:

“Inside of me there are two dogs. One is mean and evil and the other is good, and they fight each other all the time. When asked which wins, I answer, ‘The one I feed the most.’” (Chief Red Cloud, Lacota).

I really enjoyed each of these little pieces of wisdom, which had a relevance to their chapters.

So, did I enjoy this book? Yes, definitely. It is not a deeply convoluted story in the vein of Agatha Christie or PD James, but the plot works well, the characters are all well-rounded and believable, and for me this was a brilliant story to dive into and relax with – and it is very difficult for me to find books that achieve that for me. The people, the locations, the storyline and the aphorisms all worked well for me.

I was going to say, if you like the writings of … but then I couldn’t think of any writer quite like Jack Spittler. I guess the overall plotting is rather like Dick Francis – it is a good, strong, cosy crime story at its heart. All I can say, really, is that I enjoyed it enormously. It’s well-written and it’s different.

So, for the first time for a friend who gave me a copy of his own book, I can happily state it’s a Highly Recommended!

November 19, 2021

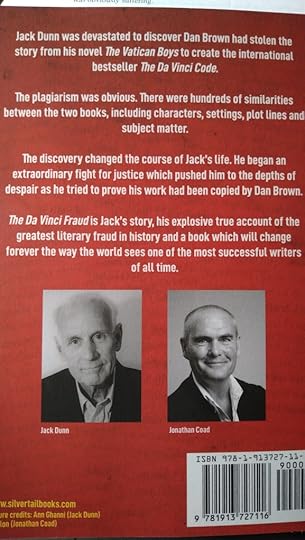

Review: THE DA VINCI FRAUD, by Jack Dunn and Jonathan Coad, published by Silvertail Books

Phew. Where to start with this one?

Okay. When I wrote THE LAST TEMPLAR, back in the far-distant days of March 1994, not only did I know that this would be the start of a glittering literary career, I also knew that my research had been impeccable, the characterisation superb and the plotting without fault.

Then that blasted man Dan Brown wrote a book which was apparently rather good. I think he took all my money. I’m not alone in thinking this. Other fellows, like Henry Lincoln, Richard Leigh and Michael Baigent, thought Brown had ripped off their own book, THE HOLY BLOOD AND THE HOLY GRAIL, which I personally thought was a dire confection of conspiracy theories and guesswork. I did read it, and it was an interesting read, but there was one point in the book where the authors suggested that if you, the reader, could accept a few little points, then …

Well I read their few points, and for me they were all of them ridiculous, but then I had conducted my own research. THE HOLY BLOOD AND THE HOLY GRAIL had some stunning conclusions. First among these was that Jesus didn’t die on the cross, that his bloodline continued to the present day, that there was an ancient “Priory of Sion” which had protected his bloodline ever since – or something along those lines. To be honest, it’s been so long since I read it, it’s only the highlights that remain with me.

As to the first two – well, no. I don’t think so. Then we come to the Order of Sion – which was a fraud. Look it up for yourself, but it was the rather amusing creation of a man called Pierre Plantard in around 1956, who I think probably invented it as a practical joke. He claimed that he was the direct descendent of the Merovingian kings, that the Priory was created in about 1100, and had various illustrious members over the centuries: Leonardo da Vinci, Botticelli, Sir Isaac Newton, and I think various other historically notable characters who simply could not have been involved. It was a ridiculous hoax – hence my suspicion that it was never intended to be serious but was only a practical joke to see how far Plantard could fool the media of the time.

Leigh, Lincoln and Baigent, however, wrote a pleasant book that sold by the pallet. They made good money from it. And then they lost it. They read a copy of THE DA VINCI CODE and concluded that Brown had basically pinched all their research. And he had. No one who reads Brown’s book can conclude anything other than that. But he said he had used it as part of his research, that was all, and since their work was historical, it was only fair that he should use their researches to give veracity to his own book.

Leigh and Baigent decided to take the matter to law. Lincoln decided against.

Well, I followed Leigh and Baigent’s case through the courts, and I admit, I felt very sorry for them. As far as I was concerned they had written an interesting fiction. And Brown had swallowed it in one gulp, then said it was all his own research. The judge was dubious about that. In fact he was quite damning about some of the evidence put forward by Brown. But in law, he didn’t see that Leigh and Baigent had a case. The two were told to pay £3,000,000 – a truly staggering sum for mere authors to pay. These were not multi-millionaires.

Although they tried to appeal the case, they lost that too, and such a massive award was catastrophic for them. Leigh died a short while later of a heart attack, and Baigent lingered on for another six years, constantly pursued by Random House’s lawyers, until worry and strain brought about his death too.

So far, so sad. I spoke once to Baigent, and he seemed a thoroughly pleasant guy. To my shame I didn’t realise who he was at the time, and was rather dismissive of his book, but back then I’d had my fill of conspiracy theorists telling me they knew where the Templars met still, that there was a worldwide Order which was planning world domination ( pretty ineffectually, if you ask me, since it’s already taken them over seven hundred years ), and that they knew the true location of all the Templars’ wealth. Which I do too. Since, when the French King stole all the Templar assets, he had them all itemised and valued. So we all know where the assets went: to the French crown. And the ledgers are still there to prove it in the Louvre.

But this book is not about snowflake conspiracists and theoreticians. This is a man’s own story, and it is beguiling, very sad, and ultimately heartening. It’s a story of determination, knocks-back, renewed courage, and finally success, possibly, against the odds.

Jack Dunn started writing in the 80s, and although he tried to win a major publisher, he was soon to discover, as do most authors, that publishers are not that keen on books! He collected rejections, as do so many writers. His first book, THE DIARY OF WILLIAM GOFFE ( 1982 ) was republished as THE ANGEL OF HADLEY (1989 ), which is a story rather like the British “Angel of Mons” story, about a ghostly angel helping save retreating British troops in the First World War. In Dunn’s book, the ghost was to save Hadley from an attack by native Americans during the colonial period.

Dunn enjoyed writing that book so much that he was hooked. He wanted to write more, and because he was at the time gainfully employed, working in medical supplies, it took him six years of research and travel to get the plot down for his next book: THE VATICAN BOYS. He began it in 1996, and it was published by a “small New England publisher, Modern Memoirs, in 1997.”

He says, “The Vatican Boys was a labour of love, and the second novel in which I had used my story formula, where painstakingly-researched historical facts were interwoven with historical fictions of my own …”

Now, I have to make one ( no doubt startling ) confession here. I have never read THE VATICAN BOYS – nor have I read, or seen the film of, THE DA VINCI CODE. So I am going solely on the content of this book and on the word of the two authors. And that makes it a very intriguing book indeed, because Jonathan Coad is not an ordinary author. He is the solicitor who backs Jack Dunn’s case that the “novel written in 1996 was plagiarized to create the best-selling thriller of all time, a book which spawned a series of blockbuster movies and launched the career of one of the world’s most successful authors.” ( Quoted from page one of THE DA VINCI FRAUD, Introduction, by Jonathan Coad. )

I know that there are many solicitors who would be eager to publicize their client’s case, hoping no doubt for a little fame to attach to their names in the process, while merely increasing their client’s risk of a defamation case or increased damages while remaining personally safe. Jonathan Coad has not done that here. As far as I can see, he has deliberately placed himself in the firing line of Dan Brown and Dan Brown’s publishers. He states that “if Jack and I are right, Dan Brown is a charlatan, thief, liar and perjurer who has won court cases on both sides of the Atlantic under false pretences; and his publishers, Penguin Random House, have colluded with him and tried to prevent this book being published, despite having been provided with overwhelming evidence that Dan Brown is just as we characterise him.”

For those who are interested in Mr Coad, a quick internet search will suffice. If you can’t be bothered, this link will take you to his website and list of clients. It’s pretty impressive: https://www.jonathancoad.co.uk/clients/

So here the story is getting more interesting, isn’t it? A reputable UK and international lawyer is tying himself to Jack Dunn’s case.

So how did this book come about? It began when Dunn was signing copies of his own books in a bookshop, and the staff came to him to express their shock and dismay on reading Dan Brown’s book. One example: “‘You ought to take a look at this, Jack,’ Henry said. ‘This guy’s copied The Vatican Boys cover to cover.’”

So he read Brown’s book, and it “sounded familiar. I had published that story eight years ago.”

Dunn tried to sue Dan Brown and his publishers in the US. But the judge didn’t accept his case and rejected it out of hand, refusing even to allow a jury trial to see the evidence tested. And as a part of that, Dunn had to sign away his rights to appeal the case in the US. And there things would have remained, until someone else met him at an awards ceremony and asked him what he thought about ANGELS AND DEMONS, because that was a direct copy of elements of THE VATICAN BOYS in places ( although then it followed its own plotline ). Dunn could not accept that he must allow Brown to get away with stealing his work again, and he started to look into how to gain recognition for his efforts. But that was a very difficult matter. Even when he was introduced to Jonathan Coad, a very successful media lawyer, the likelihood was he would get nowhere. Coad, like all good solicitors, was skeptical at first, until he began to study the evidence, and then he was won over after some forensic investigations into “fictional facts”. No. Buy the book if you want to read about them!

This book is not the angry self-justification of an author who feels wronged. Well, yes, in fact it is, but it is a reasoned and well-written summary. And it explains why Dunn and Coad decided to write the story – which is basically to try to force the hands of Brown and his publishers into taking court action in the UK. Dunn and Coad and their publisher are all convinced of the truth and rightness of their evidence. It remains to be seen whether Brown and his publishers will dare seek to test it in court.

So, what did I think of the book? It is a book written by a man who is deeply offended – he’s upset by the treatment he’s suffered at the hands of a multi-millionaire he feels has stolen his efforts; he’s upset by the failure of American justice to protect him from an unfair legal system and powerful multi-nationals; he’s upset by the feeling that he’s been forced to struggle, when his efforts, his work, have led to another man raking in a fortune. Most of all, he’s upset that his research and his writing have not been recognised.

Does this story read like an angry complaint? Yes – but only in a very minor way. The fury is there, but it’s been carefully edited and mitigated by a professional lawyer. As a result this book reads more like a thriller – it is not a whining protest. The grievance is there, but it never overwhelms. And if true, his grievance is entirely justified.

The book is set out as a simple narrative, taking the reader from the first moment he learns about THE DA VINCI CODE, to the present day. After that there is a chapter which is Jonathan Coad’s own address to the court, explaining the basics of the case as he sees it. That is from pages 185-202. After that are three appendices: first, the letter from Jonathan Coad to Penguin Random House’s legal department; second a comprehensive analysis of the common elements between the two books; third an analysis of specific elements common to both books which includes certain fiction-facts demonstrating plagiarism. These appendices run from page 204-296. That alone gives some idea of the degree of commonality alleged.

I am no lawyer, and I have not read either THE DA VINCI CODE or THE VATICAN BOYS, so I am in no position to comment on the validity of the allegations made. But as a reader, if only a half or even a quarter of the characterisation, or plot, or commonalities of themes were true, I would have thought they would demonstrate beyond any reasonable doubt that Brown stole Dunn’s ideas and research and passed it off as his own. The publishers tried to destroy Dunn for attempting to protect his work, as they were with Baigent and Leigh, hounding them both, I think literally, to death.

I have to admit, this is a book I have to recommend very highly indeed. I found it utterly compelling reading, and consumed it in one sitting yesterday. Jack Dunn and Jonathan Coad have produced a masterly story here, and I wish them luck in taking the matter to court and demonstrating that justice can prevail, even some two decades after the event.

November 12, 2021

Review: SLAVES AND HIGHLANDERS; Silenced Histories of Scotland and the Caribbean, by David Alston, Edinburgh University Press

This is a proof copy. The final printed version may well have a different cover.

This is a proof copy. The final printed version may well have a different cover.This is one of those books which leaves the reader thinking. It raises many questions, mostly about slavery and the British – which yes, means Scottish and English – responsibility for slavery, as well as the French, Dutch and other European nations who ran slave plantations. But this is much more. It is thought-provoking, and I make no apology for this rather lengthy review. This book really does deserve serious consideration and I only hope I can do it justice.

It is not a huge book. My version (a pre-publication proof copy without Foreword or Index) weighs in at a reasonable three hundred and sixty five pages, of which three hundred and twenty four are text, the rest notes. The main thing about it is, it is written by a master. The sentences flow and it is astonishingly easy to read and absorb for such a difficult subject.

I have often mentioned that I usually prefer to pick up a book by a dead historian than a modern one. Why? For the simple reason that people like Hoskyns and Finberg knew how to tell stories. Their books were not dry history, they were wonderful stories that took the reader back into a different time. They were above all dedicated to inspiring and enthusing others. Historians in the past knew that they had to fascinate readers. Modern writers all too often write quick history to prove that they are worthwhile to the university. If they don’t publish enough, they may find their funding reduced – or removed. And there are too many historians who are in reality agitators for one or other political theory, and will twist and distort the truth in order to promote their own views. It makes for tedious reading.

But there are exceptions to this rule: Ian Mortimer and Geoffrey Marsh, for example. Now I have to add David Alston to my growing list of authors I not only rather like reading, but whose work is genuinely gripping.

I will take the first couple of paragraphs from this book to demonstrate what I mean:

“Only a few minutes’ walk from my home in the small community of Cromarty in the Scottish Highlands, a seventeen-year-old black student was stabbed during a brawl outside the local school. A recent immigrant from the Caribbean, he had been shunned by other students, and often carried a knife, which he had previously brandished in confrontations with older boys. This time his opponent – who was younger and claimed to have been hit first – retaliated drew his own knife, jinked to one side and stabbed the black teenager in the thigh.

“Both boys were from troubled backgrounds. The black student was probably an illegitimate child sent to Scotland for education, with no close family in a strange country. His white assailant, at the age of five, had lost his father in an accident at sea, the family had struggled financially, his two sisters had died …”

So far, a rather unremarkable story. Stabbings are all too common, after all. However:

“… I know you will not have seen it reported in the media. It happened two hundred years ago, in 1818.”

I read that last sentence with real surprise. I was reading this while relaxed, and was assuming that the story presented was a modern tale. Alston goes on to say that “The white student was sixteen-year-old Hugh Miller, who after being thrown out of school started work as an apprentice stonemason but went on to be a leading figure in Scottish public like as a journalist, geologist, writer and churchman.” He was a church reformer who helped create the Free Church of Scotland. His history is well documented.

But who was the black victim? Why was he there in that small town – was he the only black student? Were there many? What would have led to him being uprooted from the Caribbean and dropped into Cromarty? These questions plagued Alston, and he began to research the boy’s life. In the late 1990s, when he set out on his investigation, “Scotland was confidently telling itself about its involvement – or lack of involvement – in the sordid business of slavery and the brutal regimes of slave-worked plantations in the Caribbean.”

From this beginning, Alston has become an expert on Scottish involvement in the slave trade, slave ownership and the slave-worked plantations in South America, the Caribbean and beyond. This book is a firm rejection of the revisionist history that pretends Scotland had little or nothing to do with slavery.

As he demonstrates, a quick look at the historiography shows that “major works in Scottish history at the time [the 1990s] were a catalogue of silence.” Michael Lynch’s Scotland: A New History (1991), The Open University and University of Dundee’s Modern Scottish History (1998), had no mention of slavery in their indexes. Thomas Devine’s The Scottish Nation (1999) and other books only mentioned slavery in so far as there was Scottish involvement in arguing for abolition. It makes it seem as if that there has been a determined effort to revise Scotland’s history – perhaps due to the independence movement, to try to emphasise a non-existent Scottish separateness, a kind of Scottish exceptionalism; that to be Scottish is to be kinder, nicer, more humanitarian.

Why was history being rewritten in such a manner, to demonstrate that Scotland and the Scottish had nothing to do with slavery? Alston suspects an unconscious bias. He mentions the Museum of Scotland. Originally, according to Dr Sheila Watson, “the curators had expected that the collections would lead the story. However, during its planning stage the curators were told to make the collections fit the narrative – the story of the Scots people over time.”

As a result the section on Scots in the British Empire implies a solely benign or positive influence. As Ian Jack said, “If a museum in England imitated the Edinburgh Museum’s treatment of Empire … there would be a lynch mob at the gates.”

All these quotes are from the first chapter, which works as an introduction to the book, setting out why Alston was so interested in this aspect of Scottish involvement in slavery and how historians have, for the most part, tried to ignore the more negative areas of Scotland’s past. To close on this, he quotes Professor Ewen Cameron’s proposal for a discussion of Scotland’s history, and the imaginative view that Scotland was a “colony” of England.

“Nor is the identification of Scotland as a downtrodden colony any longer confined to the margins of political debate …The distinguished historian Linda Colley – English-born but based at Princeton University in the USA – recently expressed her surprise at the number of Scots who believe Scotland’s relationship with England to be a colonial one … This is not only largely nonsensical as history, but offensive and insulting to many non-white, non-European peoples who did, in fact, find themselves oppressed or even dispossessed by the ‘British’ Empire.”

After this introduction, Alston goes on to look at specific areas. The first part of the book covers “The African Slave Trade, The English ‘Sugar Islands’ and Scots in the Expanding Empire” and demonstrates that the Scottish were involved in the trading of slaves around the Caribbean and the Americas. When the French ceded the islands of Grenada, Tobago, St Vincent and Dominica, there was a “disproportionately high number of Scots who seized the opportunities” available to them. He looks at the fortunes of several families, for example, the Frasers of Boblainy, who were not rich, but who became slave owners, and profited from the expulsion – Alston describes it as “ethnic cleansing” – of the indigenous peoples.

The second part looks at “Northern Scots in Guyana on the ‘Last Frontier’ of Empire”. These four chapters look at Demerara, Essequibo and Berbice, and Scottish involvement there. Again, when territories were taken by the British, Scottish slave owners, overseers and managers were quick to take advantage. Even when the British Empire had abolished slavery, these areas flourished because of their Scottish owners’ continued use of slavery.

The most shocking – and to me disturbing – element in this story is the question of how a very small white population managed to subdue much larger populations and hold them as slaves: deliberate terrorism. It was clearly due to “the centrality of terror in the operation of large-scale plantation slavery.” The fiscals’ and protectors’ records demonstrate this. As Alston notes, it was “Not simply fear of punishments – which included branding, nose slitting, gelding, whipping and pickling (rubbing salt into the wounds) – but spectacular displays of violence whose effects were believed to extend into the afterlife.” These included beheadings, bodies left dangling in chains for vultures to feed on.

Planters like Colin Macrae from Inverate explained the crucial importance of his engineer, a head boiler [for boiling his sugar cane] or his leading man, for without any one it would have been very difficult to control his up to three thousand slaves. His nephews Alexander and Farquhar Macrae later wrote manuals on management of plantations. This section, especially the chapter “Guyana – Voices of the Enslaved” makes for harrowing reading.

The third part is “Entangled Histories – The Legacies of Slavery in the North of Scotland”. This is where Alston gets into the meat of Scottish involvement away from the managers, owners, overseers and others who worked at the coalface of the industry. This looks at the money made by Scottish investors and how it was spent: on improvements to agricultural land, manufacturing and even the fisheries, as well as finance and banking. However Alston develops this theme. “Control” and “accountability” were soon to be watchwords in Scottish business, and as concepts of modern accounting practices grew, “rooted in the rationalism of the Scottish Enlightenment”, Alston follows Thomas Devine’s The Scottish Clearances, in which he considers the dispossession of so many small farmers. The smaller farmers could not compete with the larger, and many were deprived of their livings. “The same educated and increasingly professional class of estate factors and surveyors … sought the control and accountability which was simultaneously being pursued, of necessity, on the plantations.” From this, he goes on to consider whether Scotland was “Colonial or Colonized?”

Finally, in the fourth part, “Reckonings”, he looks at a series of questions that we should all be considering. “How should we understand this history and how should we respond to it? What responsibilities do we have for the past? Should we apologise? Make reparations?”

More than that, he asks “what might be the particular responsibilities of historians?” to that, I am happy to answer that, so far as I am concerned, the key responsibility of all historians is to the truth.

This has been a lengthy review because I believe the history, the research conducted, and the questions raised about the rewriting of history and the “reckonings” from this period in Scottish history should be considered more widely.

The subject matter is admirably clearly set out. The research is comprehensive and compelling. The multiple histories are fascinating and at times harrowing. But the writing is superb. David Alston has produced a very timely, extraordinarily easy book to read that I will be referring to regularly.

In case you need to ask – I’d say this is very highly recommended indeed.

September 18, 2021

Review: Living With Shakespeare: St Helen’s Parish, London 1593-1598

History, as I learned at school, even at its very best and most exciting can, if a teacher or writer tries hard enough, become dull and tedious in the extreme. Which is why I picked sciences for A level and dropped history. I loved history as a subject, and had studied the medieval period, Victorian era and both World Wars in my spare time. But I have a dreadful memory for dates, and I was convinced I’d never get a good qualification – let alone a well-paid job.

The history of a parish is not the sort of subject to enthuse. It is an already dry, uninteresting topic. Or so I thought before I picked up this book. This truly magnificent book. I say magnificent because Geoffrey Marsh has produced a wonderful history in this book.

I’ve never read any of Marsh’s previous works, and do not know the man, but if this is anything to go by, I’ll be looking out for other titles by him. He is Director of the Department of Theatre and Performance at the Victoria and Albert Museum, so his life has been bound up, I imagine, with studies of Shakespeare’s life. His learning has been put to marvellous effect in this book.

Why is this so good?

First, for me, because he gives a superb feel for the city. He runs through the streets like a man who has walked them in Shakespeare’s time. The book begins with a startling and horrible scene: this is the time of the 1593 outbreak of plague. It is “thirty-five hours before the dawn of St Crispin’s Day. In the heart of London, a young boy lies motionless of a straw mattress. His sunken cheeks, greying face and feeble breath make it clear that he is dying. Alongside him, his brother Abraham, drenched in sweat, tosses and turns, hands clasping and unclasping with spikes of pain. Despite the autumn evening chill the room feels steaming hot, as if the boys’ fevers can heat the fetid air. Across the room, their sister Sara tried to sleep. Upstairs, in the low garret under the roof tiles, two tearful servants girls lie wide awake, holding each other, trembling at the scene they know is just beneath them.”

Baldwin, the boy’s father, is there with Melchior Rate, a local Dutch preacher, as his son dies. Later Baldwin has to take his son’s body downstairs, to be left outside for the gatherers to take away. “Tomorrow Baldwin will lug Melchior’s heavy body down the same stairs, to be followed over the next ten days by his son Abraham, his daughter Sara and one of the servant girls.” He has already taken his wife’s body and another son out. Soon the second servant girl will also die. Of a household of seven, he alone survives.

I have not given away much of the book in these quotes and comments – this is all on the very first page – and you should not get the impression that the whole book continues in quite such a devastating manner, but Marsh has a real ability as a writer (and if he ever wants a fresh career, I would suggest historical thrillers would be right up his street), and can thrust the reader straight into the scenes he is painting.

This is not a story just of plague, though. It is first and foremost a tale of the people who lived in the small parish of St Helen’s. To write about this, he covers London’s life and the people who inhabit the area. However it is also telling about Shakespeare and the period when he lived in the parish, and to do that, Marsh also talks about the theatres of the area, especially Burbage’s Theatre, the problems of building it, the difficulties of financing it, the on-going issues based on the eruption of plague and the consequent loss of income (there are real shades of our recent experiences with Covid shutdowns here), and Burbage’s disputes with the lease-holder and others.

From there we move to the parish itself, and speculating why Shakespeare might have chosen this area to live in. We are given a quick guide to the area, its history and the various people who would become his neighbours. But St Helen’s was a growing commercial hub. People from all over Europe were arriving and trying to make a living free from the persecution they suffered in France and the Low Countries. We are introduced to doctors, lawyers and musicians before we’re taken to look at bewitchment by way of a specific case.

After all this, there are a series of Appendices which take us on to more detail about the type of accommodation available, and then on to study individuals in the neighbourhood.

There are very few writers who can bring the past to life in such an accessible and easily absorbed fashion. Marsh has a light touch as a writer. His prose is direct but never harsh. It is a real joy to read something so detailed, well-researched, fluent and informative.

Even better, he has discovered a fabulous trove of engravings and watercolours that show the streets as they would have been. He has maps, pictures of the houses, illustrations from contemporary pamphlets and books, and a wealth of other documentary evidence. These break up the text nicely so that it can be left happily on a coffee table to entertain visitors – but the real value lies in the text.

This is a book I had to read from cover to cover as soon as I received it, and it is a book I will return to many times over the coming years as I continue my Jack Blackjack series.

I have reviewed many books here on my blog, and many have had the “Highly Recommended” stamp of Jecks approval. I have to admit, though, that this is easily the best non-fiction book I’ve had the pleasure of reading this year.

I am enormously grateful to Edinburgåh University Press for sending me a copy to review.

Living With Shakespeare: St Helen’s Parish, London 1593-1598, published by Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 9781 4744 7972 1