D. Thourson Palmer's Blog, page 9

March 14, 2016

RAZE – 010

I have forgotten how stupid I was so long ago. At the time, especially after my still recent escape from the Lonireilian army, I thought that I was very clever indeed. I realized my error quite shortly after I stopped hearing the sounds of the others of my company, and immediately before I was struck with most of a tree.

My pursuit of Green Skive, who, at the time, I believe I thought of only as “the damned green woman,” led me along a steep slope dotted with black stones protruding from the snow, obfuscated by smoke-needled trees. I ran along the incline, avoided rocks with my feet slipping, my every breath a labor. The woman’s ghanavocha’s trail was clear, fat-footed round marks pressed deep into the snow and fallen needles beneath. It snorted and trumpeted somewhere ahead, echoing strangely between the trees. Staggering, not knowing what I would do when I caught her except that it would be violent, I forged ahead on shaking legs with my crescent sword out and bright. I remember the silence that fell between sounds. Every noise was distinct and alone in the nothingness: the snort of the ghanavocha, my own ragged breath, each crunching, lost-sound step in the snow.

I rounded a towering rock, on which the trees clung with glistening coal black roots in grasping knots between mounds of moss showing through white powder. She was ahead, waiting and watching on her mount. Behind her stood a rocky wall and more clinging trees, climbing to the bright sky where their greedy fellows basked and took all the sun for themselves and shaded the box canyon. When I saw her, waiting, and heard nothing behind me, I knew my error. That is when the borovoi hit me with a tree trunk.

To be in combat is a series of decisions made with little information, more with memory and instinct and a guess as to what is most likely to happen. At the time I did not understand this, nor was I yet much of a fighter, although, to be sure, I was much, much better than I had been as a child when the Lonireilians came to my family’s farm.

However, any thought or idea one has about how to fight, to face a foe, how to approach and retreat strategically, and to attack, is dashed out of one most swiftly by the unexpected impact of the better part of a tree.

The blow sent me off my feet. Time ceased and then I was in the snow, my face bleeding, my breath truly gone. I failed to breathe. My body would not respond, and panic seized me as I had seldom known, a full-being, mindless terror as my lungs spasmed uselessly. Then, I gasped and the pain that followed my intake of breath was magnificent, for lack of a better term. It was mesmerizing in its fullness, blinding, overwhelming. My entire chest turned to ice and burned. The pain was such that it took a moment of thought, of decision, to determine whether to take another breath again, or to resist doing so forever. Thankfully, my body makes wiser choices than I.

The sound behind me was a deep-throated shudder, geese on the wind mingled with an ox’s bellow. I rolled over in the snow and rock to see a creature wielding a tree trunk in one claw. It was twice my height, and I am not a short man. Matted deep-brown hair covered it and its arms were long enough to reach the ground. A grand and foul mustache drooped from between its snout and snarling blackened teeth, which jutted at angles from spit-flecked, leathery lips. Two antlers, like an elk’s, crowned its head. It raised the trunk again.

An imperative seized me. I scrambled away as the wood fell, splintering, sending wet chunks careening about me. I stumbled up, swung my blade, hit something, tried to run away. The borovoi gave chase and its feet hammered the snowy earth, the reverberations shaking my legs. I changed direction, turned, and sliced. Before my stroke fell, the back of the beast’s hand sent me to the snow and stone again. It hurled my body skidding along the rough earth and, once more, I lost my ability to breathe. Sound receded, no longer muffled by snow, but by the blanket of void drawing over me.

I managed to look over my shoulder, prepared to see nothing by my death falling on me in the form of a hoary, enormous claw.

The damned green woman swept behind the borovoi as it loomed over me. Her first slash caught its ankle, cutting the tendon. The creature staggered and left me, swinging for her, but she anticipated the blow as if it had announced its intention. She was below it, leaping down from her mount, her glaive raised. The blade shore away a part of its arm as it swept over her. Before it could recover, she lashed its sides, carving more flesh. It roared, hammered down with the remains of the trunk, but she let out a shout and, lightning fast, struck the makeshift club. Her polearm shattered the wood in a shower of splinters. On the backswing, she sliced its stomach and it staggered. With another cut, its arm fell away. The creature bellowed again, the same honking shudder, and the green woman’s last slash cut its throat.

It lurched about, less an arm, hamstringed, thick blood draining from its throat and stump. The hot spatters fell over me and it staggered away, collided with the canyon wall, then fell in a shower of crumbling stone.

I lay, covered in stinking, steaming blood, and watched Green Skive clean her blade on the shaggy fur-covered arm still twitching at her feet. Dust hung on the air from the collapsed stone. She came to me, walking with her glaive like a staff, and offered me her hand. It was all I could do to raise my arm enough to grasp her by the wrist, but she pulled me upright with a strange, sudden surge of motion. It was as if I weighed nothing, and in that moment, I would have believed it. She was stone, statue permanent; I, nothing but a passing fog.

Once I was on my feet, she pulled down her scarf to reveal a knowing, somewhat surprised half-smile. She was young, my age or perhaps a little more. Her skin was black, deeper and cooler than a Serehvian’s, and her were waterfall green, pale and alive. She spoke, a language I did not know. The tone was one of amusement, the inflection of a question. The sound of the tongue she spoke was round, big, percussive and musical. I stared dumbly, unable to speak, let alone understand. My mind boggled at what I had seen her do.

She waited, staring, then whistled high and sharp. Her ghanavocha trotted to us from where it had fled. As I watched, the green-dressed woman went to the fallen borovoi, a creature men saw only in nightmares and told of in hushed voices, and cut away its grand antlers with two snapping blows. She returned and slung them over the ghanavocha’s saddle as the creature shuffled and trumpeted, its eyes rolling. Then, the woman I would later come to know as Green Skive reached to the saddle and took the bag she had stolen from my caravan. She offered it to me, inclining her head, and spoke again in the tongue I did not know.

I was empty, drained of fear, my head clear as the skies and just as thoughtless. In that instant, I changed and learned. I guessed what had happened, and it was not until some time later that she affirmed my suspicion. She had come to kill the borovoi, but even so mighty a beast would not approach so many as my company by the road. And even for one of Green Skive’s skill, it would have been foolish to face such a creature without bait. I had become her lure. It could have been any of us, but it was me. She offered back what she had stolen, a lure for a lure, because she was no thief, or at least, was no thief on that day.

She said something again as I took the bag. I thanked her in my tongue, finding it rough and crude. She gave no indication if she understood or not, but she nodded, smiled wide, vaulted to her saddle, and started away. All I could think, standing there in the wreckage and snow, bleeding and covered in another’s blood, was what lie to tell to my company. What could I tell them that would result in my greatest gain when I returned with the stolen cargo, to salvage both the caravan and, more importantly, my company’s reputation.

March 12, 2016

Moving ahead with the Victorious Death

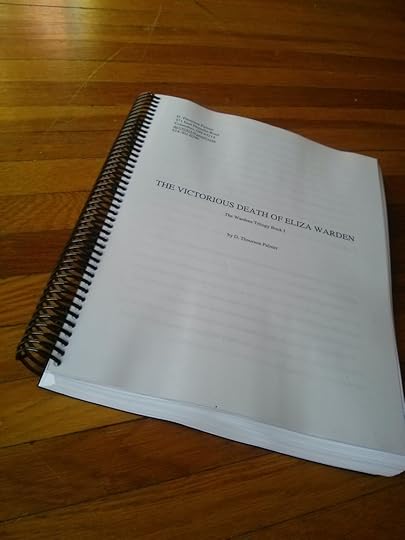

So this is the first time I’ve seen it all printed out:

Yep, that’s the full, printed manuscript for The Victorious Death of Eliza Warden. It’s huge. Plenty of space for me to fill with red ink.

Coming up is the difficult process of trying to separate myself and my own knowledge from the experience of someone picking up the book sight-unseen. I’ve had some great input from beta readers (thanks! You know who you are) and more coming in (keep it coming!), as well as my own ideas about what needs to change.

March 7, 2016

Ours Is the Storm makes top 25 list!

Hey all, I ran across this yesterday which was a pretty cool find. BestFantasyBooks.com compiles several lists every year of their favorite works, and for 2016 Ours Is the Storm made their top 25 best indie fantasy books list! (You have to scroll down quite a bit, but there are a bunch of other great books to check out on the list too.)

It’s a great honor to be on there with a number of the top fantasy writers working outside of the big traditional publishers. There are a lot of us and I’m humbled that Ours Is the Storm is so well-regarded.

Check out BestFantasyBooks.com for great fantasy recommendations and new books.

RAZE – 009

Green Skive. The first time I saw her I gave chase, but I did not yet know her name, nor did I know that she was leading me. I was not pursuer, I was prey.

I knew, however, that she had assaulted the caravan of which I was a part, during a long, slow slog up a near-impassable road. Snowy Kalughnor was far from the place that had been my home. I was twenty-two. Eight years had passed since the Lonireilians took me from my parents’ farm, and one since I’d finally escaped their army.

The caravan carts, heavy things with banked sides and arrow-slits cut through the black whorled wood, covered overtop in steepled sailcloth to keep out the damp, were up to their iron axles in the snow. It was light, powder, but there was so much the oxen bellowed and shoved and farted their way up while we, the newest of the mercenary company, pushed behind, our gloved hands and shoulders sopping and freezing, pressed up against the backs of the carts. Our tevkas, the senior members of the mercenary company, called a ululating rhythm for us to heave by. The man beside me stank, as did we all, unwashed, unshaven for a week and sweating even as we froze beneath layers of skins and foul hides. His beard was covered in ice crystals from his breath and his own snot. He was Lonireilian, called Estevo, and I had first met him outside my family’s home while he smoked, when his company destroyed my home and my life.

We heaved in time with the singsong, rough shouts of the tevkas, driving our feet into sliding snow, forcing our shoulders against the wagon. Behind me, more than fifty men and five other wagons did the same. Their task was made somewhat easier by the trail we had left, trampled snow and churned earth and ox shit.

“If I had known,” I said to the Estevo, “that we were being hired as packbeasts instead of guards, I might have stayed in Lonireil.” I was lying, but he laughed anyway.

“If we’d stayed in Lonireil,” he said, “we’d be far worse off than packbeasts.” Estevo grunted as he slipped and I pulled him back upright.

“If you fall, I’ll actually have to start pushing,” I said. He laughed, but his grimace was all too plain.

We heard a cry, a new cry. Warning, a bell, a horn. We stopped and backed away, the cart very nearly sliding onto us, but the oxen surged and held it on the steep hillside on the snow-covered road. Exhausted, gasping, Estevo and I and the others spun at the warning bell and the new shouts and our hands went to spears, to axes and bows. I heard a pistol shot as I turned. That would be our leader. Only he had a powder weapon.

The hill below us was a mess, five other carts, thirty more shaggy oxen, fifty mercenaries and dozens of the weak traders who paid us. The air was filled with the steam of breath and sweat. All this stretched below on the vast bright hill, snow so white that it, truly, harmed the eyes. It made some men blind. The others, Kalughnorians speaking the grating tongue I barely understood, joked that my pale eyes would burn out of me in a week and indeed, they felt as if they might.

To either side of us stood dense black forest, tiers of trailing white on glistening coal-colored trees with short needles. The snow blew from them in streams like glinting edges on blades of wind. Among the carts below were men and horses and hump-backed ghanavocha, huge creatures, squat and brown, with hair to the ground and tall, gently curved pointed horns. Then, flying and cutting through it all, I saw her. I saw her for the first glorious moment and in my mind that moment stretched into the infinite.

Love at first sight is for poets, and though I name myself one, I have also said that I am old and have little time for falsehoods or embellishments, trivialities or nonsense. I did not love her then. I did not lust for her. I was exhausted, stinking, frozen through from sweat and ice, the kind that rakes your face with hot needles, rasps at every exposed inch of skin. I did not love her or want her, but the moment was perfect and I treasure it. It was looking on autumn leaves drifting over a stone cliff into a desolate gorge. It was a single thistle, dry, thorns covered in frost, standing against the bitter wind.

She rode like an icebreaker ship through the mercenaries on the back of a ghanavocha, carrying a glaive in one hand, the long, edged blade blinding. She swung the haft in a wild arc, perfect in its savagery, and three of the mercenaries, my tevka and two others, fell in gouts of crimson that sang on the frozen air like rubies. She directed the beast and it plunged amongst the others, waving its horned head. Silver caps decorated the tips. Silver bells jingled on its reins and tack, and green and silver embellishments and saddle blanket caught the too-bright sun.

We ran to surround her, but she was elemental. She dismounted in a whirling leap, her green greatcoat dancing. The beast fended off my company while she raced to the nearest cart and, in one blow, smashed open the side with her glaive. I felt the impact, truly, through the earth and snow. A gout of wind blew up. Snow fell from the nearby trees.

She seized something from within, a bag, and spun it over her head as a weapon in tandem with the glaive. In two steps, she cut down another of us, leapt to her ghanavocha, plunged into the forest. The remaining four tevkas cried out and our master, the rasakonova, gave chase on his ghanavocha. We chased as well, shouting, shrieking, and the woods took us.

I ran, me and my brother Estevo, for this was the chance. Whoever took her down would gain her ghanavocha and her weapon and armor. There would be no more pushing and stinking in the ox shit behind the cart. My breath came out of me as if dragged, clawing, but in the dark of the wood my eyes hurt less. Estevo fell behind, and with him half of our paired ambition. As the other mercenaries fell behind me as well, fell gasping in the snow, I ran on. Each of them that fell gave me hope. Each was one less rival. I stole their breath, their strength, for I’d none left of my own. I passed men on horseback, tevkas on snorting ghanavochas. I raced over rock, slipped, plowed through snowbanks, dodged black tree trunks. I raced on because I saw her. She slowed, turned, looked, brandishing the sack like a prize.

Her eyes were green, greener than the banner streaming from her saddle, her face hidden by an embroidered scarf that was the color of new mezakh shoots after rain in spring. Her eyes burned straight through me and then she turned and rode on and I followed. The prey, chasing the hunter.

February 29, 2016

RAZE – 008

I gave no thought to my callous intent, my airs of maturity and stoicism. I ran, letting the cigarette fall in the dirt, ran to the house, to where some of the company had come outside to smoke and take the air after dining, through the door, to where others yet sat at the board and ate and drank our brandy, ignoring the screams. At my bursting in they stood, drew weapons, but I ran heedless and burst into the back room from whence the screams came and there two of the men held my mother down upon the bed and tore at her bright blue robes while she screamed.

I told you I was a big lad; my arms were thick and heavy for a boy of fourteen. With a flailing, thoughtless blow I struck the nearest man and the force of it threw him off her. He lurched down, against the earthen wall and the floor. A crack issued from him, the sound of a stew-bone buckling between your teeth. He convulsed but I seized the other man, lifted him, threw him. He stumbled but did not fall and I stood there, beside my weeping, wailing mother who covered herself and her eyes and pulled her torn robes. I looked back at the door while a man convulsed, unable to breathe or move or speak, on the ground beside me. My breath heaved out of me. Tears blurred my vision, rage and fear and through them the doorway filled with angered soldiers, cruel, tall, shouting. They came in and I readied myself to fight.

Shall I tell you I beat them? Chased them out? How a strength of rage came upon me, or a divine will bent to aid me, or how a latent and hidden destiny manifested itself in flae and thunder? That I drove them off, though they left me near-dead?

As I said, I am too old for fabrications. Likewise, I am too old to dwell on some things overmuch.

They hurt me. They came and took my arms as if I was a child, and indeed I was, and I was helpless and weak and could do nothing, nothing but bear what they did to me after, to teach me, to show me my error. I knew at the time I could not bear it and yet I did and I am still alive. Shall I tell you of the shame that haunted me at my violation? I think you’d rather I did not.

I killed one of theirs, made him suffer, and so I was made to suffer likewise. They violated my mother next, saying it was my fault, and then beat my father and my siblings, and before it was over they brought us outside. They dragged me, for I could not walk and I could scarcely see through my tears.

“Killed one of ours,” the commander in white and gold said. He spoke in his slippery, lazy accent, and without his helm and visor he was thin faced, with a gold mustache and neat beard as he looked down on me. A small scar notched the top of his mustache, beside his nose.. My father and mother and siblings were in the dirt beside me. “Killed a soldier. Does that make you a soldier? A warrior, eh boy? Do you feel like a warrior?” His men laughed. I don’t recall what I did, but at that time I thought all my tears were spent. I was wrong.

“You’ll be a soldier,” he said. “I’m short by one man, now. You’ll have to do.” The others chuckled again. “But first, Weckar has need of something.” He seized Punam’s arm, my youngest sister, the little one, and dragged her screaming from my mother. His men knocked her down and threw down my brother and Navat, and meanwhile my father lay face-down in the dirt like a dog and begged and did nothing else. I arose. I didn’t think I could and all I was was pain, but they knocked me in the dirt again.

It was not a Lonireilian name. It had no music. I could not guess who me meant, but immediately I knew. The lacquer-faced woman, with her red mouth and black eyes, drew signs in the air with her hands. She invoked Skertah theurgy, the summoning art. She spoke words I couldn’t understand, words in Lonireilian. They coiled through the air, roiling and winding, then jabbing with sharp consonants before subsiding again into lazy, careless curls only to stab out again syllables later. To this day, the sound of Lonireilian pierces the back of my neck.

Weckar, the lacquer-faced woman, took a thin knife from her belt. She seized my young sister from the captain. She killed her, and while I found new stores of tears, the wind howled around the demon called Weckar in a voice of knives. She called up the knife wind. It was her, and, as I later discovered, others like her. She called it from the realm of spirits and commanded it.

This is how it began. I have told no one this part of the tale, save the woman who will kill me when my telling is done, the woman who is known the world over as Green Skive.

February 22, 2016

RAZE – 007

The Lonireilian soldiers threw a tent down in the dirt and the crushed grasses for us. When I could stand, I helped my parents erect it while under guard of one of the white-armored foreigners. The others ransacked our house, threw out my mother’s few books, our clothes; they threw away a fine bright shell I had found the time I had gone to Ibandran, by the sea. It broke and the pearly pieces scattered in the grass, glassy shards devoid of meaning. I had brought it to my father as a gift when I found it. He had kept it, and they’d thrown it away. My blood surged in me, but then, looking at the armored guard, my heart quailed.

Do you think I was a coward, so young, so long ago? For a long time I did. For many, many years. Now, in my old age, understand fear a little better.

My fear could not blunt the disgust and anger I felt at my father’s acquiescence. While we raised the canvas and narrow poles of our temporary home, I watched him. He worked with his face turned toward the dirt and he said nothing.

Later, while my mother prepared food for all the company – all those interlopers and murderers – while she prepared mezakh and roasted ox and flavored it with sesame and sumac and our meagre supply of salt, the soldiers spoke to one another in their own tongue. They drank our wine and our brandy and spat it on the floor. The looked lasciviously at my mother and again my blood rushed hot to my face, and again my fearful heart quailed.

The lacquer-faced woman stood outside, looking north. The wind seemed to sigh around her although she did not move, not even with a rising and falling of the shoulders to show her breathing. She did not eat or drink. She did not move one step after leaving her mount.

Our guard, a young man, stood smoking near our tent while my father and brother and sisters ate in silence and while mother cooked beside the house. After we ate I banged my spoon down on the ground as if it was a table. The dull, quiet thud of wood on mat on grass was no proper sound and my face flushed as I stood and stomped out of the tent. The guard looked up, then upon seeing me went back to his cigarette. He dismissed me. I was no fear, no concern to him. I was nothing.

My sister, Navat, came out after me. While I kicked the grass and went around the tent, she followed. “Heshim. Heshim, come back inside.”

“I don’t want to be inside.”

“You can’t leave. They said to stay in the tent.”

“I don’t want to. Leave me alone,” I said.

She came behind me and took my hand. I turned, disgust filling me, anger burning hot in my chest and fingertips, but I pulled my hand away and saw her red eyes, her pinched black brows and trembling lip. I squatted down beside her. “I just want to be alone.”

“You aren’t leaving us, are you?”

“I just want to be outside.”

“Heshim,” she said, her black eyes scouring mine, “do you hate papa?”

“Yes,” I said. The realization shook me, but saying it was like blowing onto the base of a flame. “He let this happen.”

“It was those people. Not him.”

“He let them hurt mother. Hurt me.”

She shook her head and she put her arms around my shoulders. It smothered me and my throat clogged shut with tears. I don’t remember what she said, but when she spoke I told her to go back in the tent and that I wouldn’t be long. I should have said something else. Anything. My chance was gone. So chances and choices go, with us blind until the end is made.

I saw the guard watching me over his glowing cigarette from his place beside the tent while Navat went back inside. The sun was falling. I stood there, waiting till the tears had left my eyes, while I watched the guard watching me. The red glow of his tobacco lit his face from below like the face of a khren, from the teachings of Lord Salat, like a thing of fire and glass and smug malice.

The scent of his weed drifted to me; acrid, alluring. My parents did not smoke. I approached. “Can I have some?” I asked, unsure what else to say.

The guard stared for a moment, then reached into a pouch at his belt and produced another of the rolled up cigarettes. I took it and he lit it for me with his, and then I inhaled the smoke and struggled for all I had to keep from coughing. My lungs spasmed, like a bird was in my chest scratching to get out. I looked to the tent and my father watched me smoke with our enemy and his face went wretched, and I smiled.

“What’s your name?” the soldier asked. He was taller than me, thinner, with dark eyes that looked as if they guarded something clever.

“Heshim il-Naban.”

“You’ll be Heshim il-Lonireil now.” The man spoke the same lazy, accented Serehvan as his commander did.

“I suppose so,” I said. It sounded strange. It wasn’t a proper name. I wondered then, for the first time, why we name ourselves for a place; why we draw a line around ourselves when those we dislike most are within it, with us, sharing our names.

“Nice farm.” The man spat.

“I don’t like it.”

“Why would you?” He worked his tongue about his mouth as he looked around. “This place is a shit hole. What do you do here?”

“Here, we turn shit dirt into shit-tasting grain.” He laughed at that. “We do grow poppies, though.”

“I’d give my left nut for a smoke of that.”

“A grand bargain, for certain,” I said. He laughed again, and I was about to say I could get him some poppy when screams shredded the still night. They came from the house.

February 16, 2016

RAZE

I’m pleased to announce the beginning of a new project. RAZE is a fantasy fiction web serial I will be writing for free on my website, dthoursonpalmer.com, and updating weekly. It is the story of RAZE, the self-proclaimed world’s greatest warrior. Born Heshim, the son of poor grain and poppy farmers, Raze is taken from his home and begins the journey of a lifetime, frought with violence and tragedy, but also love and a search for wisdom and purpose.

In a prison cell, held by the enemies who first set him on his journey, facing execution at the hands of the woman he loves, Raze tells of his life, his travels, the wisdom he gained, and how he came to be known as the one whose name means “to destroy completely.”

My name is Raze, but my name as it was given by my mother and father was Heshim il-Naban, and I have been called by many others in many lands. Raze is the name I have chosen for myself, after some thought and time, and it is the name by which I’ve come to be known. It is true. It is destruction, to completeness. It is unmaking.

I am greatest warrior the world has ever known.

Hear the tale of RAZE at dthoursonpalmer.com/raze

Share and tell your friends

February 15, 2016

RAZE – 006

I drew near and two of the soldiers dropped from their saddles and unsheated their cavalry sabers. They had white-lacquered bucklers on their arms which shone in the sun emerging from the dust clouds, white trimmed in gold. Their armor was made of lacquered paper, although I didn’t know it at the time. You may scoff, but properly made paper armor will stop blade or bullet, is light, is simple to make. As my current captors will tell you, they have used paper armor in Lonireil since ancient days. It was many-layered, folded, beautiful. They wore white breastplates and tall masks with tall slits and their pale eyes burned through fiercely.

These two rushed at me, swords glinting. “Who else is here?” the man beside the strange, lacquer-faced woman said. He pointed at my parents with a riding stick. “Who else?” His voice was slippery, the accented words missing their heads and tails.

The two soldiers brandished their blades at me and I stepped back, but when I saw the fear in my parents’ eyes as they gaped at me, I dropped the meat in the dirt and raised empty hands, balancing the hide with my knife wrapped up in it between my shoulder and my head. By the house, Dasinur bellowed at the raised voices and swung her hairy head about.

“My children, my babies,” my mother said. “No one else. I’ll get them. No one else is here, only my young ones.”

“No one else,” my father agreed. “Please. We have farm goods and little more. These things are for you.” He gestured at the baskets of grain and poppy they’d brought out. “Take them, please.”

“Three others.” The voice that came from the lacquered woman sighed out from the red opening of her mouth in the smooth, shining face. She had waves of black hair that looked untended, lank. The pale eyes – they were almost white, blue-white irises in a dark circle in white orbs behind a mask that was not a mask, it was her face. Those eyes were her eyes and the lacquered, smooth, shining visage was her skin, but wrong, so wrong. They looked out as from inside a shell. “Three children. No more,” she sighed. “It will serve.”

“Dismount,” the commander said. “Secure the domicile and surrounds. Send word to the next nearest squads.” Two of the riders broke away, one going west, the other east. Indeed, in the distance to the east I could see the flash of what might have been white armor, another group of soldiers. “By order of the Eminence of Lonireil, these lands and this home are seized. You are citizens of Lonireil now, and we will billet here until needs we move forward.”

“Billet?” My mother stepped back toward the house, her arms outstretched in her deep blue robes as if to shield it. Two of the soldiers made to pass her. She stood in their way while my father gaped. They seized her and threw her down.

I lunged and roared. Lord Salat teaches that we must protect the weak. But, I was foolish and unschooled, then, in violence. If I were then as I am today, I would have fallen on the twenty of them like a wave on sand. I would have unmade them.

As I think on it, the lacquer-faced woman might prove a challenge even today.

The two menacing me lashed out. It is lucky I held the hide on my shoulder. A careless blade fell on the hide, but the blow knocked me down and the other’s killing stroke missed. They set to me with the hilts and with their boots and in the space of a breath it was over and I lay bloody and wheezing. My father ran to me and they knocked him flat. My mother lay where she fell, weeping, and in the space of two more breaths the two soldiers entered our home and came back out and tossed my brother and sisters into the dirt like refuse, where they cried and crawled to my mother.

“Is this resistance that we must suffer?” the commander asked from his perch above us. I, my eyes clenched and my insides a knot and my head pounding, hammering, from back to front in searing waves, could only look up. I held my tears at the back of my throat with all the strength I had left. “Need there be more violence?” the commander asked again.

“No, no take what you will. Please, don’t hurt us,” my father said.

“We will confiscate your goods. You grow mezakh?”

“Yes. It is yours, please, eat.”

“And poppy?” We sold and traded poppy for our meager income. It was enough to buy what we needed, beyond mezakh. The two crops were our lives.

“It is yours.”

“We will take your goods. A caravan will come tomorrow or the day after for the poppy. You will be housed while we billet here. We will provide you a tent,” the commander said.

“Tent?” I could hear my father’s tears and I hated him. My own tears strained for release but the hate beat them back. I hated him for giving what we had. For not fighting. It was his charge to protect us, was it not? Was he not a man? I did not understand, then, what I do now. Why did I hate him and not my mother? Why did I hate him more than the Lonireilians, the war-makers, who did this? “What will we do if the winds return?” my father asked.

“We are the winds,” the Lonireilan commander said. “We command them.” Beside him, the lacquer-faced woman sighed, and the sound was the sound of the knife wind.

Enter your email to subscribe *

Follow me

Tweet

February 14, 2016

RAZE – 005

I went to the back of the house, around the back which faced the long free plains in the north and from which, on a clear day, I could see the city of Naban-ka. The wind was a brown haze in the north, still. I wondered if the city’s high walls would save it from the winds themselves.

The living ox lay beside the dead one, its heavy head resting on the other’s haunch. It startled at my approach and swung its hairy face this way and that. Great hot breaths snorted out from its nostrils, but at the sound of my voice it calmed somewhat. Both creatures were covered in thick dust, dust which rose from the living one in gray clouds as it got unsteadily to its feet. Its eyes were caked shut with dust. The dead one’s leg had stayed out of the lee, out in the wind, and the hair was gone and the thick hide red and bloody and the creature stank.

The living one stood where it was, eyes caked shut, breathing heavy breaths and heaving its great hairy sides. Its head swung to and fro. When I moved closer to the fallen one, the living startled again and backed away a wary pace.

The dead one’s skin was tough and had mostly withstood the first blasts of scything air. I inspected the hide, hoping we might salvage at least that much, and when I reached its face I saw what had killed it. Its eyes, too, were caked in dust, but they were bloodied and open, little ruins. The dust had bored its soft eyes. I looked up at the living one and finally I noticed the dried fluid that crusted the hairs and dirt in great tear-streaks down its face. It was blinded, but, by some chance, the wound had killed one ox and left the other alive.

It took some time to clean the living ox’s eyes but they were useless, scarred and bloody. The creature stirred its head but it calmed itself when I spoke. While my father and mother gathered our tools and saw to food and checked the damage to our drying shed and storage cave in the hillside, I brought the living ox’s harness. It smelled the familiar leather and let me harness it to the dead ox.

“Come, Dasinur,” I said to it, using the Serehvan words for ‘eyeless one.’ “Good, nice Dasinur, come along.” I coaxed the ox to pulling its dead comrade out away from the house. There were no flies. I guess the wind tore them all up. So the knife wind was good for something, in the end. Dasinur pulled the dead one out to the east, and all the while I guided her steps and her great hairy head swung this way and that. On our way, I looked south and saw the soldiers in gold and white drawing nearer, though it might be hours yet before they came, if they came slowly.

We dragged the dead ox into the east, not far from a narrow creek which came all the way from the southern mountains, and which was low but moving with clear water. I left the dead ox and then had a thought, and I walked Dasinur to the creek. She smelled the water and drank for a long time, so long I pulled her away so she might breathe and not be sick. We waited a few moments and then I let her have a little more before walking her back. Last, I walked back to the dead ox with my knife, and there I cut away and saved the hide and I cut away some meat that did not seem too sour.

The men in white and gold did not come slowly. When I looked up from my bloody work they were close, nearing our fields. I saw my father waiting beside my mother with some baskets before the house. I quickly washed away some of the blood, for it was up to my elbows, and then rolled up the heavy, smelling hide and tucked my knife in it and took the meat and ran back. My parcels were heavy but I was big and hefty even at that age and they slowed me only a little.

I reached the house as the soldiers did. There were twenty of them and two others, in finer armor with more gold. They all rode on fat camels, as they do in Lonireil, and they bore spears and crossbows. One of those in front bore no weapons. Her skin was hard and shining, like glazed brown clay, and her face like a smooth clay mask with holes cut in for black eyes to look out and a red, red mouth.

Enter your email to subscribe *

Tweet

RAZE – 004

I didn’t weep. At the time my pride at staving off tears bore me through the first day.

Outside, the wind rushed and slashed. It roared against the house. After the first few moments, a strange sound came to us, a bellow that was discordant and inconstant, a rising desperation. It moved and settled at the back of the house, sheltered from the knife-wind, where it came and went for some time. We clustered in a sleeping room, far from the sound and sheltered by inner mud walls in case the cutting wind made its way through the front of the house. “It’s the oxen,” father said. His voice was an old man’s, timid and tired and hopeless, and my stomach turned at his show of weakness. He was right, though. The braying changed and what had been two oxen moaning became one.

For two days, the wind howled and the single ox outside wailed in pain and sorrow. My siblings wept. Mother held them but I would not cower beside her. Father said little more. He sat with his knees up and his head between them. We rationed water and I gave my share for my young brother and sisters. I paced or sat; there was no sleeping. The sound of the wind gouged my ears. Looking at my young brother and sisters, I saw only wriggling pink and gray mice and blustered to myself, in silence, that I could muster the strange mercy I had learned in my sixth year if we ran out of water. We had enough for a little time.

On the fourth day, the winds died. Before any else could move, and before my mother could stop me, I raced to the door and threw it open. The wood splintered at my heavy touch; I was a tall youth, and burly from work and good eating in recent years.

The wind, dying, still stung my face, but it did not cut. The door fell to pieces, deep-gouged by the knife-wind, a plain now riddled with canyons, that had weathered a millennium’s worth of blowing sand. The grass was all flattened and cut.

Out to the south, between our home and the mountains, was a troupe of some twenty men. Amongst the rocks and dead grasses they moved, dressed in white and gold. The sun shone from their armored caps, blinking bright at me from leagues away. The winds still stirred the fallen blades around them.

“Soldiers,” mother said. She had joined me at the door.

“Naban soldiers?” asked father.

Mother said, “Lonireilian soldiers. In white. How did they survive in the wind?”

“Lonireil. We must do as they say if they come here,” my father said. He stood behind her, looking at the ground. “We must do as they say. We’ve nothing for them to take.” Again my stomach turned and I made a face at his words. I wanted to spit, but Lord Salat teaches that one does not disrespect a parent. My father met my gaze, then looked back at the dirt. “Heshim, listen. Do as I say, for your family.”

“I will,” I lied.

Enter your email to subscribe *

Tweet