Gar Alperovitz's Blog, page 11

May 2, 2013

April 29, 2013

When Martin Luther King Came to Cambridge: An Historic Conversation about an Historic Moment

with LANI GUINIER * GAR ALPEROVITZ * BYRON RUSHING

with LANI GUINIER * GAR ALPEROVITZ * BYRON RUSHING

There can be no freedom without peace and no peace without justice.

—Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, April 22nd, 1967

Monday, May 20th 7:00PM

Christ Church Cambridge, Zero Garden Street, Cambridge

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s legendary “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, an anniversary that is going to be marked by celebrations and commemorations nationwide this summer.

But four years after he gave that speech, Rev. King came here to Cambridge, to Harvard Square, with a different message for America: one not about a dream of equality of rights but the dangers of war. The war in Vietnam was killing and maiming young Americans at an astonishing rate and the casualty rates for black soldiers were far higher than for whites. At home, President Johnson and the Congress were cutting precious funding for the War on Poverty in favor of the War in Vietnam.

America, King feared, was being both wounded and corrupted by what was happening 9,000 miles away; so he came to Cambridge to issue a new call, one as important in some ways as his “I Have a Dream” speech, one that would link the civil rights and antiwar and antipoverty workers across the nation in a new common crusade for justice, equality, and peace.

But why Cambridge? And what did King say? What did he hope to achieve?

On Monday, May 20th, at 7PM, join Harvard professor Lani Guinier, co-founder of Vietnam Summer Gar Alperovitz, and State Representative Byron Rushing, a legendary civil rights and antiwar legislator here in Massachusetts in an intimate conversation as they discuss “When Martin Luther King Came to Cambridge….”

Forty years after Dr. King spoke, part of his dream was met: America elected its first African-American President. But what else remains to be realized? And what of Dr. King’s challenge in Cambridge has been taken up by Barack Obama, and what not? What linked civil rights, antiwar, and antipoverty efforts into a common cause in Dr. King’s mind that day in Cambridge and how are each of them faring today?

By special arrangement, the conversation among Lani Guinier, Gar Alperovitz, and Byron Rushing takes place in the very room at Christ Church Cambridge where Rev. King issued his challenge. Join them as they reflect on his legacy and its importance today.

Seats are limited for this historic event, but it is free and open to the public.

Street parking available. Harvard Square Red Line T stop one block away.

Parish Hall doors open at 6:45PM.

More information about Vietnam Summer: Vietnam Summer Evolves From Phone Call To Nation-Wide Organizing Project

April 17, 2013

The Question of Socialism (and Beyond!) Is About to Open Up in These United States

Little noticed by most Americans, Merriam Webster, one of the world’s most important dictionaries, announced a few months ago that the two most looked-up words in 2012 were “socialism” and “capitalism.”

Traffic for the pair on the company’s website roughly doubled from the year before. The choice was a “kind of no-brainer,” observed editor at large, Peter Sokolowski. “They’re words that sort of encapsulate the zeitgeist.”

Leading polling organizations have found converging results among younger Americans. Two recent Rasmussen surveys, for instance, discovered that Americans younger than 30 are almost equally divided as to whether capitalism or socialism is preferable. Another Pew survey found those aged 18 to 29 have a more favorable reaction to the term “socialism” by a margin of 49 to 43 percent.

Note carefully: These are the people who will inevitably be creating the next American politics and the next American system.

As economic failure continues to create massive social and economic pain and a stalemated Washington dickers, search for some alternative to the current “system” is likely to continue to grow. It is clearly time to get serious about a different vision for the future. Critically, we need to be far more sophisticated about what a meaningful “systemic design” that might undergird a new direction (whether called “socialism” or whatever) would entail.

Classically, the central idea undergirding various forms of “socialism” (and there have been many, many forms, some of which use the terminology, some not) is democratic ownership of “the means of production,” or “capital,” or more simply, “productive wealth.” Quite apart from questions of exploitation, systemic dynamics (and “contradictions”), the core idea is simple and straightforward: Those who own wealth – and the corporations that operate it – have far more power to control any system than those who don’t.

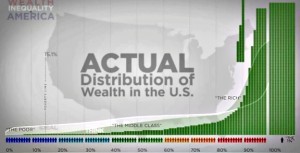

In a nation in which a mere 400 people own more wealth than the bottom 180 million together, the point should be obvious. What is new in our time in history is that the traditional compromise position – namely progressive, or social democratic or liberal politics – has lost is capacity to offset such power even in the modest (compared, for instance, to many European states) ways the American welfare state once represented. Indeed, the emerging direction is to cut back previous gains in many areas – not to sustain or enlarge them. Even Social Security is now on the table for cuts.

Perhaps the most important reason for the decline of the traditional reform option is the decline of labor: Union membership has steadily decreased from roughly 35 percent of the labor force in 1954, to 11.3 percent now – a mere 6.6 percent in the private sector.

Along with this decay, and give or take an exception here and there, major trends in income and wealth, in civil liberties, in ecological devastation (and the release of climate-changing gases), in poverty and many other important indicators have been “going South” for several decades.

It is, accordingly, not surprising that dictionary look-ups and polls show interest in “something else.” If, as is likely, the trends continue, that interest is also likely to increase. But what, specifically, might that “something else” entail? And is there any reason to hope – even as interest in the word “socialism” grows in the abstract – that we might move from where we are to “some other system” that might nurture equality, liberty, ecological sustainability, even global peace, more than the current decaying one we now have?

New Models of Socialist Structures

The classic model of socialism involved state (national) ownership of most large-scale capital and industry. But it is now clear to most observers that the concentration of such ownership in the state also commonly brings with it a concentration of political power as well; hence, the model can be detrimental to democracy as well as liberty (to say nothing, in real world experience, of the environment).

Alternative places to locate ownership have been suggested by different traditions: in cooperatives, in worker-owned firms, in municipalities, in regions, even in neighborhoods. Some of the advantages and challenges involved in the various forms are also well-known:

Starting at the ground level, there appear in virtually all studies to be very good reasons - for small and medium-size firms - to arrange ownership through cooperatives and worker-owned and self-managed enterprises. This is where direct democratic participation is (or can be) strongest, where a new culture can be developed and where a very different vision of work can evolve. Very solid proposals have been offered in such books as John Restakis’ Humanizing the Economy: Co-operatives in the Age of Capital and Richard Wolff’s Democracy at Work: A Cure for Capitalism (on what he calls “worker self-directed enterprises”).

On the other hand, for larger, significant-scale enterprises, worker-ownership may not solve some critical problems. When worker-owned large firms operate in a market-based system (as proposed by some progressive analysts), groups of workers in such firms may develop narrow interests that are not necessarily the same as those of the society as a whole. (It may be in their interests, for instance, to pollute the community’s air and water rather than pay cleanup costs – especially when the firm faces stiff competition from other private or worker-owned companies.) Studies of worker-owned plywood companies in the Northwest found that all too easily workers developed narrow “worker-capitalist” attitudes (and conservative political views) as they competed in the marketplace. Nor does such ownership solve problems of inequality: Workers who “own” the garbage companies are clearly on a different footing, for instance, than specific groups of workers lucky enough to “own” the oil industry.

Often here – and in several other variants of socialist ideas – it is hoped that a new culture (or ideology) or progressive forms of taxation, regulation and other policies can offset the underlying tendencies of the models. However, there is reason to be skeptical of “after-the-fact” remedies that hope to counter the inherent dynamics of any model, since political power and interest group influence often follow from ownership irrespective of good intentions and the hope that progressive political ideals, or ideology, will save the day. If the attitudes nurtured by the plywood co-ops turn out to be the norm, then new worker-owned companies would likelynot generate strong support for regulations and taxation that help society at large but restrict or tax their own firm.

Let me stress that we simply do not know whether this might or might not be the case. It is, however, a mistake to assume either that socially responsible regulations can be “pasted on” to any institutional substructure (especially if they create costs to that substructure), or that institutions will automatically generate a sufficiently powerful cooperative culture and institutional power dynamic in favor of regulations and taxation even if it adds costs to their own institution and is detrimental to the material interests of those involved.

To get around some of these problems, some theorists have proposed democratically managed enterprises that are nonetheless owned by the broader society through one or another structural form. Although workers in the “self-managed” firm could gain from greater efficiency and initiative, major profits would go to the society as a whole. Still, note that in such cases, too, the incentive structure of the competitive market tends to create incentives to reduce costs – for instance, by externalizing environmentally destructive wastes. Also, when there are economies of scale, market-based systems generate very powerful pressures to adopt new technologies and prioritize growth (or lose out to other firms that also are under pressure to grow and adopt new technologies) – and this dynamic, too, runs counter to the needs of an ecologically sustainable future.) John Bellamy Foster’s The Ecological Revolution, among other efforts, gives depth to the ecological foundational arguments further systemic designs must consider.

Designing for Community

We are clearly at the exploratory stage in connection with these matters, but the really important question is clearly whether a new model might inherently generate outcomes that do not require “after-the-fact” policy fixes or attempted fixes it is hoped the political system will supply. Especially since such “fixes” come out of a larger culture, the terms of reference of which are significantly set by the underlying economic institutions, and if these develop competitive and growth-oriented attitudes, the outcomes are likely to be different from those hoped for by progressive proponents. Lest we jump to any quick conclusions, it is again important to be clear that no one has as yet come up with a serious “model” that might both achieve efficiencies and self-directed management – and also work to create an equitable, ecologically sustainable larger culture and system. All have flaws.

Some of the problems and also some of the design features of alternatives, however, begin to suggest some possible directions for longer-term development:

For instance, a third model that has traditionally had some resonance is to locate primary ownership of significant scale capital in “communities” rather than either the state or specific groups of workers – i.e. in geographic communities and in political structures that are inclusive of all the people in the community. (By definition geographic communities inherently include not only the workers who at any moment in time may only include half the population, but also stay-at-home, child-rearing males or females, the elderly, the infirm, children and young people in school – in short the entire community.)

Community models also inherently “internalize externalities” – meaning that unlike private enterprise or even worker-owned companies that may have a financial interest in lowering costs by not cleaning up environmentally destructive practices, community-owned firms are in a different position: If the community chooses to continue such practices, it is polluting itself, a choice it can then examine from a comprehensive perspective – and in a framework that does not inherently pose the interests of the firm against community-wide interests.

Variations on this model include the “municipal socialism” that played so important a role in early 20th century American socialist politics – and is still evident in more than 2,000 municipally owned utilities, a good deal of new municipal land development and many other projects. “Social ecologist” Murray Bookchin gave primary emphasis to a municipal version of the community model in works likeRemaking Society: Pathways to a Green Future, and Marxist geographer David Harvey has begun to explore this option as well. (As Harvey emphasizes, any “model” would likely also have to build up higher level supporting structures and could not function successfully were it left to simply float in the free market without some larger supporting system.)

Current suggestive practical developments in this direction include a complex or “mixed” model in Cleveland that involves worker co-ops that are linked together and subordinated to a community-wide, nonprofit structure – and supported by something of a quasi-planning system (directed procurement from hospitals and universities that depend in significant part on public financial support). An earlier model involving joint community and worker ownership was developed by steelworkers in Youngstown, Ohio, in the late 1970s.

The Jewish theologian Martin Buber also offered a community-oriented variation based on cooperative ownership of capital in one geographic community. He saw this “full cooperative” (and confederations of such communities) as an answer the problems both of corporate capitalism and of state socialism. Buber’s primary practical experimental demonstration was the Israeli cooperative commune (kibbutz), but the principle might well be applied in other forms. Karl Marx’s discussion of the Paris Commune (and of the Russian village commune or mir) is also suggestive of possibilities in this direction.

In the various community models there is also every reason to expect that specific communities will develop “interests” that may or may not be the same as those of the society as a whole. (Again think of communities located on top of important natural resources versus others not so favored.) The formula based on community ownership, however, may have a potential advantage that might under certain circumstances – and with clear intent – help at least partly offset the tendency for any structural form to produce narrow interest-group ideas and power. This is the simple fact that a fully inclusive structure that nurtures ideals of “community” – as opposed to ideas of individual ownership, on the one hand, or worker-group ownership of specific firms, on the other – may offer greater possibilities for building a common culture of community, one in which norms of equal treatment and common interest are inherently generated by the structural design itself (at least within communities and possibly beyond.)

To the extent this is so, or could be nurtured, a systemic design based on communities (or joint worker-community ownership) might both allow for decentralization and also for the generation of common values. A subset of issues also involves smaller scale geographic community ownership, in the form of neighborhoods. And such a model might also include a mix of smaller scale worker-owned and cooperative forms, and even (larger scale) state and nationally owned public enterprise as well – a structural form that is now far more common and efficient in many countries around the world than is widely understood.

Questions of Scale

Social ownership by neighborhoods, municipalities, states, and, of course, nations (all with or without some formula of “joint” worker ownership) are not the only models based on the fact that geography is commonly inherently inclusive of all parties – and therefore potentially capable of helping nurture inclusive norms and inclusive cultures. A final formula (for the moment) for significant scale and ultimately large industry is also based on geography, but at a different level still. This attempts to resolve some of these problems (and that of genuine democratic participation) by defining the key unit as a region, a formula urged by the radical historian, the late William Appleman Williams, as especially appropriate to a very large nation like the United States. It is not often realized how very different in scale the United States is from most European nations: Germany, for instance, can be tucked into a geographic area the size of Montana. Nor have many faced the fact that our current 315 million-person population is likely to reach 500 million over coming decades (and possibly a billion by the end of the century, if the US Census Bureau’s high estimate were to be realized.) During the Depression, various regional ownership models like the Tennessee Valley Authority were proposed, some of which were far more participatory and democratic in their design than the model that is currently in place. Legislation to create seven large-scale, publicly-owned regional efforts was, in fact, supported by the Roosevelt Administration at certain points in time.

Many other variations, of course, also have been proposed. The Parecon model, for instance, would attempt to replace a system of market exchanges with a system in which citizens would iteratively rank their preferences for consumer goods along with proposed amounts of proffered labor time. Proposals, like that of David Schweickart in After Capitalism, pick up on forms of worker self management, but also emphasize national ownership of the underlying capital. Seth Ackerman, in arecent essay for Jacobin, urges a worker-controlled model, but stresses the need for independent sources of publicly controlled investment capital. Other thinkers, like Michael Leobowitz in his book, The Socialist Alternative: Real Human Development, have taken inspiration from Latin America’s leftward movement, and especially from Venezuela, to articulate a participatory vision of socialism rooted in democratic and cooperative practices. Joel Kovel in The Enemy of Nature argues that the impending ecological crisis necessitates a fundamental change away from the private ownership of earth’s resources.

And, of course, the question of planning versus markets needs to be put on the list of design challenges. Planning has its own long list of challenges – including, critically, who controls the planners and whether participatory forms of planning may be developed drawing on smaller scale emerging experience and also on a much more focused understanding of what needs to be planned and what ought to be independent of public direction. (Also how the market can be used to keep a planning system in check.)

As noted, there is also the question of enterprise scale – a consideration that suggests possible mixes of different forms of social ownership: where to locate the ownership and control of very large scale firms is one thing; very small another; and intermediate still another. Most “socialist” models these days also allow for an independent sector that includes small independent capitalist firms, especially in the innovative high-tech sector.

Related to all this is the question of function: The development and management of land, for instance, is commonly best done through a geographic institution – i.e. a neighborhood or municipal land trust. Public forms of banking and finance tend also to be best anchored in (though operated independently of) cities, states and nations. Though medical practices must be local, social or socialized health systems tend to work best in areas that include large populations – i.e. states or nations. In some cases, quite apart from efficiency considerations, ecological considerations make regions especially appropriate. (One of the rationales, originally, for the Tennessee Valley Administration had to do with managing a very challenging river system.)

On the Ground Now

Finally, there is much to learn from models abroad – particularly Mondragon, on the one hand, and the worker-cooperative and other networks in the Emilia Romagna region of Italy, on the other. The first, Mondragon, has demonstrated how an integrated system of more than 100 cooperatives can function effectively (and in areas of high technical requirement) – and at the same time maintain an extremely egalitarian and participatory culture of institution control. The Italian cooperatives have demonstrated important ways to achieve “networked” production among large numbers of small units – and further, to use the regional government in support of the overall effort. Though the experience of both is extraordinary, simple extrapolations may or may not be possible: Both models, it is also important to note, developed out of historical contexts that helped create intense cultural and political solidarity – contexts also of extraordinary repression by fascist regimes, Franco in Spain, Mussolini in Italy. Finally, although the Emilia Romagna cooperatives are effective in their use of state policy, both models are best understood as institutional “elements” that may contribute to a potential national solution. Neither claims to, or attempts to, develop a coherent overall “systemic” design for a nation.

These various abstract considerations come down to earth when one realizes that there is far more going on, practically, on the ground related to the ownership forms than most people realize – a great deal that is not covered by the increasingly hobbled and financially constrained press. For a start, around 130 million Americans – 40 percent of the population – are members of one or another form of cooperative, a traditional collective ownership form that now includes large numbers of credit unions, agricultural co-ops dating back to the 1930s, electrical co-ops prevalent in many rural areas, insurance co-ops, food co-ops, retail co-ops (such as the outdoor recreational company REI and the hardware purchasing cooperative ACE), health-care co-ops, artist co-ops and many, many more.

There are also many, many worker-owned companies structured in ways different from traditional co-ops – indeed, around 11,000 of them, involving 10.3 million people, in virtually every sector, some very large and sophisticated. Technically, these companies are structured as ESOPs (Employee Stock Ownership Plans) – and in fact 3 million more individuals are involved in worker-owned companies of this kind than are members of unions in the private sector. (Though there have been a variety of problems with this form, there has also been evolution with greater worker control and also experiments with unionization that in the future might suggest important additional possibilities.) Finally and critically, the United Steelworkers have put forward a new direction in union-worker co-ops.

There are also thousands of “social enterprises” that use democratized ownership to make money and use both the money and the enterprise itself to achieve a broader social purpose. By far the most common social enterprise is the traditional Community Development Corporation, or CDC. Nearly 5,000 have long been in operation in almost every US city of significant size. For the most part, CDCs have served as low-income housing developers and incubators for small businesses. Early on in the 50-year history of the movement, however, a different, larger vision was in play – one that is still present in some of the more advanced CDC efforts and one that suggests additional possibilities for the future.

Still another form of democratized ownership involves growing numbers of “land trusts” – essentially neighborhood or municipal corporations that own housing and other property in ways that prevent gentrification and turn development profits into support of low- and moderate-income housing. One of the best known is the Champlain Housing Trust in Burlington, Vermont, which traces its modest beginnings to the early 1980s and now provides accommodation for more than 2,000 households. Hundreds of such collective ownership efforts now exist, and new land trusts are now being established on an expanding, ongoing basis in diverse contexts and cities all over the country.

Since 2010, twenty states have also considered legislation to establish public banks like that of North Dakota, which has operated with strong public support for more than nine decades. Approximately 20 states have considered legislation to establish single-payer health-care plans. Nor should we forget that the United States government de facto nationalized General Motors and AIG, one of the largest insurance companies in the world, during the recent crisis. It started selling them back once the profits began to roll, but in future crises, different outcomes might be ultimately achieved if practical experiments at the local and state level begin to create experiences that might be generalized to national models when the time is right – especially if the current system continues to decay and deteriorate. (Many of the national models that became the core programs of the New Deal were incubated in the state and local “laboratories of democracy” in the decades prior to the time national political possibilities opened up).

At this stage of development, there is every reason to experiment with many forms – a “community-sustaining” direction that I have suggested might be called a “Pluralist Commonwealth” to emphasize the plurality of common or democratized wealth-holding efforts.

Getting Serious

I obviously do not hope in this brief sketch to try to offer a fully developed alternative. My goal is much simpler: First, to suggest that the questions classically posed by the word “socialism” that is now coming back into public use need to be discussed and debated by a much broader group than has traditionally been concerned with these issues; and second, to suggest further that if one looks closely there is evidence that some of the potential real world elements of a solution may be developing in ways that might one day open the way to a very American and very populist variant (whether called “socialist” or not). It is time, accordingly, to discuss the deeper design issues carefully and thoughtfully and in ways that involve a much larger share of the very large numbers of people, beyond the traditional left, who the polls and dictionary inquiries suggest may be interested in these questions.

Even as we learn more and more about the various forms and their positive and negative features and tendencies, hopefully we can engage in a far-reaching and thoughtful debate about how a new model might be created that is both systemically sophisticated and also appropriate to American culture and traditions – a model that nurtures democracy and a culture of inclusiveness and ecological sanity. Many serious and committed people on the left have been struggling with these issues and keeping the critical questions alive for decades. Even though the way forward, politically, is obviously daunting, difficult and uncertain, it is time to widen the dialogue in ways that include the millions of Americans who now seem increasingly open to the challenge.

Nor should the pessimism of the moment undercut what needs to be done: Anyone looking at Latin America 30 years ago might easily have been judged foolish to think change could occur – and that debate concerning these kinds of questions was important. Yet even during and through the pain – and the torture and dictatorship – new beginnings somehow were made in many areas and by many people. Our own course may be difficult, but easy pessimism is an all-too-common escape mechanism to avoid responsibility. It is also comforting: If one buys the judgment that nothing can ever be done, that it is impossible, one has an excuse not to try and also not to try to reach out to others. The fact is the failings of the present system are themselves forcing more and more people to explore new ideas and develop new experiments and new political efforts.

The important points to emphasize are three: [1] There is openness in the public, and especially among a much, much broader group than many think, to discussing these issues – including even the word “socialism;” [2] It is accordingly time to get very serious about some of the challenging substantive and theoretical issues involved; and [3] There are also many on-the-ground experiments, and projects and developments that suggest practical directions that are under way, but also that a new politics (whatever it is called) might begin to build upon them if it got serious.

Copyright, Truthout. Reprinted with permission.

April 8, 2013

Kind words from Monthly Review on my work and new book

From the editor’s introduction to the April 2013 issue (http://monthlyreview.org/2013/04/01):

One of the most notable left intellectuals in the United States is Gar Alperovitz, professor of political economy at the University of Maryland. As an undergraduate Alperovitz studied at the University of Wisconsin under the great revisionist historian William Appleman Williams (a frequent contributor at the time to Monthly Review). He went on to pursue a PhD in economics at Cambridge University under Joan Robinson (also an MR contributor). Alperovitz’s doctoral dissertation, which was eventually published as the book Atomic Diplomacy, constituted a revisionist historical account of the decision to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He demonstrated that Truman’s decision to use the bomb on civilian populations was opposed by U.S. military leaders—and was not so much the last act in the Second World War as the first act in the Cold War. (Truman’s objective in dropping the bomb was to force an immediate unconditional surrender—Japan had offered to surrender but the security of the emperor remained a sticking point—in order to preempt the further advance of Soviet troops into Asia and the expansion of the Soviet sphere of influence.) Alperovitz’s latest initiative is represented by his brand new book,What Then Must We Do?: Straight Talk About the Next American Revolution. He describes the systemic crisis in which the United States is trapped as one of “punctuated stagnation”: The nature of our current economic predicament, he writes, “is not [one of] collapse, but rather an odd form of painful stagnation—the hallmark of which is economic decay, with occasional significant downturns and (at best) modest and temporary upticks around a sickening, uncertain and debilitating norm” (126). [...] We strongly agree with Alperovitz that a “punctuated stagnation,” in the sense he has described it, is the most accurate reading of contemporary economic reality and sets the stage for what could be “the next American revolution.” His book can be obtained from Chelsea Green Publishing at http://chelseagreen.com.

April 3, 2013

Laura Flanders talks to Gar Alperovitz about What Then Must We Do?

Welcome to the spring of sequester and discontent. Just ahead, whatever happens in the world of politics, a world of people are going to experience yet more cuts to education, housing, healthcare, and there’s no solution to poverty in sight. Even for those who were flushed with excitement last November, the new term is already feeling like a pretty glum place. What real change is likely to come? Probably not much. By how much are real wages going to grow? Probably less. ”If you counted poverty the way every other nation in the world counts it, a quarter of our society is in poverty,” says political economist Gar Alperovitz.

So why is it then, that Alperovitz also says we may be witnessing the prehistory of the next American Revolution? What’s up?

Alperovitz believes that the storm of failure we’re witnessing creates crisis but also possibility. When states and cities have “no answers,” new ideas and new experiences have a chance to insert themselves into the mix. Indeed, look a little deeper than the money media tend to, and the US economy is pretty heterodox. Far from one “economy” we live in a “checkerboard” of systems, some of which look a whole lot like socialism.

What’s “hotel socialism”? Find out in this conversation about Alperovitz’s latest book What Then Must We Do: Straight Talk About the Next American Revolution, which comes out later this month from Chelsea Green. Alperovitz teaches at the University of Maryland. We talked for GRITtv.

Transcript

Laura Flanders: Am I describing this moment correctly? Post-election enthusiasm followed by gathering gloom?

Gar Alperovitz: I think that’s about right and rightly so. The president is committed to $1.5 trillion in cuts for the next decade and at the same time he is talking about boosting the economy. I suspect we’ll get very little change in the unemployment rate [that is] the real unemployment rate, which is probably 15% if you count the people who just don’t show up anymore.

What are the main accomplishments of Obama’s first term in your view?

The obvious accomplishment, such as it is, is Obamacare. With great buy-offs of the corporations and insurance companies, we got some people more healthcare. A very lousy deal, but nonetheless, people who would not get it are there and possibly that will force states to move in the direction of Vermont – to single-payer. Otherwise, the cost is just too high. So that’s a step in the right direction, taken badly but nonetheless.

But it’s a great case in point. The reality seeps through. Reporting recently on the slower than anticipated rise in healthcare costs [a front page story in the New York Times played up the good news for the administration], but look at the data, and the slowing rate of growth is probably because of the recession: People are going to the doctor less often.

It is a reduction in the rate of growth. The cost is still going up and the cost structure is not sustainable.

Now I look at this wearing two hats: I am a historian and political economist. When I say “the revolution” I mean we are entering an era like the Progressive Era, when at the end of the 19th century in the next two or three decades problems get worse. The political system can’t solve the basic problems. That produces the kind of developing reactions we’re seeing both in terms of protest but also in the many states and localities. The press doesn’t have any interest in, and doesn’t have any reporters who can cover it covering it, but there is a lot going on because the pain levels are growing at the local levels.

People who are invested in Wall Street and the stock market would say, “You’re mad, the market is up. We’re doing great.”

Absolutely, at that level the elites and the markets are doing very well. As they are doing well, many, many tens of millions of people are not doing well. We’re about to see a major crisis [among] the elderly because very few people have savings for retirement and the pain levels are going to grow there, which means their kids are going to be under pressure and that’s another source of difficulty.

The main thing is to look at long trends, and there is decay over 30 years in terms of income distribution, climate change, environment, poverty. If you counted poverty the way every other nation in the world counts it, a quarter of our society is in poverty – that’s to say, living on less than half of the median income. There is an underlying decay in the political system that our system can’t handle, and bound to come with that are both political protests …

The main thing is to look at long trends, and there is decay over 30 years in terms of income distribution, climate change, environment, poverty. If you counted poverty the way every other nation in the world counts it, a quarter of our society is in poverty – that’s to say, living on less than half of the median income. There is an underlying decay in the political system that our system can’t handle, and bound to come with that are both political protests …

Much more interesting are the changes in the institutions, worker-owned co-ops, neighborhood ownership. Changes are happening in the ownership of capital in many parts of the country. Ten million Americans are working in worker-owned companies; 130 million belong to co-ops of one kind of another. These are changes going to the question of who owns the capital, which is the key question in any sort of capitalist system. And I think that’s going to build out of the decay and out of the pain.

Let’s start with some examples; when you say there are examples, name a few.

The most interesting one is in Cleveland, the Evergreen Co-ops. A group of worker-owned co-ops brought together with a nonprofit corporation so that they build community, not just individual worker co-ops and a revolving fund modeled after Mondragon co-ops in Spain; so they kick back to the revolving fund to build more worker co-ops. That’s the complex; they have three or four on the ground right now, including the largest urban greenhouse in the United States producing three million heads of lettuce a year. That means every Monday and every Tuesday, and every Wednesday 26,000 heads of lettuce are put to seed. It’s a very big operation.

The most interesting one is in Cleveland, the Evergreen Co-ops. A group of worker-owned co-ops brought together with a nonprofit corporation so that they build community, not just individual worker co-ops and a revolving fund modeled after Mondragon co-ops in Spain; so they kick back to the revolving fund to build more worker co-ops. That’s the complex; they have three or four on the ground right now, including the largest urban greenhouse in the United States producing three million heads of lettuce a year. That means every Monday and every Tuesday, and every Wednesday 26,000 heads of lettuce are put to seed. It’s a very big operation.

And the people overseeing the greenhouse are workers, members of the community?

It’s a joint venture. The workers have participation and control in their co-ops, but they aren’t free-ranging. They can’t get up and go; it’s a community building operation. The distinction that is even more interesting, [there's] a lot of taxpayer money in hospitals and universities. The big hospitals and universities in that area have been brought in to purchase from this complex. They buy three billion dollars a year in goods and services.

So you have the political sphere actually investing in this experiment or in this new type of enterprise.

Yes, and several other cities are doing something very similar: Atlanta, Pittsburg. A number of cities are exploring it now, which tells you – and this is the paradigm – there is no answer in most urban areas for redeveloping low-income areas. Corporations aren’t going to do it, small business isn’t going to do it, the government doesn’t have any money …

That logic – “no answer” – is forcing innovation and that’s the paradigm logic of this decade and the next decade that gives me some hope that we are laying the groundwork for something that could get beyond [what we know now].

There’s some history here that you write about in this book, and becauseI covered it a bit last year I want you to mention it for our audience. That’s the history of the Youngstown, Ohio, steelworks and what steelworkers have done in the last year that’s very different from 30 years ago.

I was involved, in 1977 … One of the first big steel mills to go down was Youngstown Sheet and Tube in Youngstown, Ohio. Five thousand people lost their jobs in one day. They were all pink-slipped. It was traumatic, and they got together with a religious coalition and put together a plan … which was a worker community ownership of a large mill, and they got enough financing to finance a very sophisticated technical plan. They put it together, the Carter administration was going to support it for 100 million dollars and somehow, and somehow not surprisingly, that disappeared. The Steelworkers Union International was against these local guys at that point and time. They didn’t want anybody messing with ownership and they didn’t want these upstart guys challenging their leadership.

I was involved, in 1977 … One of the first big steel mills to go down was Youngstown Sheet and Tube in Youngstown, Ohio. Five thousand people lost their jobs in one day. They were all pink-slipped. It was traumatic, and they got together with a religious coalition and put together a plan … which was a worker community ownership of a large mill, and they got enough financing to finance a very sophisticated technical plan. They put it together, the Carter administration was going to support it for 100 million dollars and somehow, and somehow not surprisingly, that disappeared. The Steelworkers Union International was against these local guys at that point and time. They didn’t want anybody messing with ownership and they didn’t want these upstart guys challenging their leadership.

That’s all changed radically. Now steelworkers are leading the fight to produce worker-run co-ops with unions built right into them and they’re leading that shift within part of the labor movement. Again, viewing this historically, this is another sign of the change that I’m talking about: not only problems that can’t be solved but an evolution of ideas and institutions beginning to realize they have to move in new directions. The steelworkers are a large union. When they move, they can actually move a lot of capital into doing this and I think they will.

One of the interesting things the book describes is the dominant economic system – it’s not as dominant or hegemonic as you might think. You mention some extraordinary examples. The Texas Permanent School Fund … Talk about that.

If you get below the abstraction “we can’t do it,” you find something different actually going on. In Texas for almost 100 years they had land in ownership of the state and oil in ownership of the state

Doesn’t that sound like “nationalized”?

… Socialism! Land and the profits from this publicly-owned trust are used to fund education. That is socialism.

If you told most Texans that’s what’s happening in their state they’d say …

They’d probably say it’s a good thing because it’s Texan and they don’t see it through the idea of socialism, they see it as a good thing for our state. Indeed, if you look around – the point of this book – you find these kinds of things. Seven hundred and fifty cities are setting up companies to capture methane from the garbage and turn it into electricity, to make money and to create jobs.

Again, if you actually get beyond the big abstractions ["socialism"] the problems cannot be solved in other ways and there are these innovations going on at the grassroots level. I’m a realist, this is all preliminary stuff. Nonetheless, they are introducing into American culture and ideology the idea of democratizing the ownership of wealth in real human terms that people can understand and that has very powerful potential in terms of cracking the ideological sphere. It’s Gramscian, if you like.

Public banking is a part of this too …

Yes. The Bank of North Dakota, as many people know, is a bank that has been there for ninety years. It’s a state-owned bank, very popular among small business but also labor. Some 20 states have introduced legislation to replicate something like the Bank of North Dakota. Washington State and Oregon are the furthest along, but again, as the financial crisis comes and goes, I think we are going to see more support.

Yes. The Bank of North Dakota, as many people know, is a bank that has been there for ninety years. It’s a state-owned bank, very popular among small business but also labor. Some 20 states have introduced legislation to replicate something like the Bank of North Dakota. Washington State and Oregon are the furthest along, but again, as the financial crisis comes and goes, I think we are going to see more support.

It’s a very interesting sub-rosa movement that’s growing around these kinds of things. Banking is another area where you’re beginning to see this kind of exploring of public ownership – exploring democratizing wealth. That’s what distinguishes this from the traditional liberalism [of] “let the bankers own it, let the investors own it, and let government try to regulate.” These paradigms all involve democratizing ownership in what’s also a very American way, a very decentralized way.

Calling it the next “American” revolution gets to that point. What we’ve known as the liberal model is essentially the European model: liberalism as a check on the banks and on the concentration of power. That’s the idea of “countervailing” power: You have the Chamber of Commerce, we’ll have the AFL-CIO, a balance of forces. That’s not what you’re talking about.

That word “countervailing power” came from John Kenneth Galbraith, who believed in it but near the end of his life said, “that’s over.” He was right because mainly he had in mind labor unions. They went from 35% of the labor force organized, now down to 11% [in the public] and less than 7% in the private sector today. That force is not able to “countervail.” Let’s do what we can, I’m for labor, but they have declined dramatically. Take Vermont. They are going to have single-payer healthcare shortly, because the election gives them that power, and when they do they will displace other companies because they will have better prices and the service will be better.

Public banking, putting in a bank that people like, you are creating a displacement movement rather than simply countervailing, and a true transformation is going to have to transform who owns capital, and how institutions are organized …

Again if you see it historically rather than it’s going to happen tomorrow you can see this buildup over many parts of the country, which gives us a shot, at least, at thinking about building over time different sorts of political movements and at the same time thinking about different institutions rather than the old idea of let them own the wealth and we’ll try to countervail or beg, one or the other.

I talked with economist Rick Wolff not long ago and he said a lot of people can make a co-op without changing the power relations of the state. If you just change that the workers own something but the structures of the business stays the same, have you really changed anything?

I totally agree. I think this is the prehistory. We are introducing into American consciousness the idea that it’s important to change the ownership of wealth and the experience and practice of doing that. That is only step one. It has to have a politics that begins to generalize that [and there have to be ideas].

This is often left out of organizing, the Gramscian notion of ideas. The second part of the battle is also to introduce new ideas. What this is about in the big terms is changing ownership of capital and democratizing wealth (or the sociology of knowledge, as per Karl Meinheim’s argument.) We are building the practical basis of an idea system that needs to be raised, too, even among progressives who don’t see it that way. They still for the most part are involved with let’s protest and get them to give us something, I’m not against that; there is a lot of work to do on that front. But we are also going to need practical examples, an idea system, and a political movement. The idea system is often neglected. I write books and I don’t think ideas matter most of the time – because power matters. But when the idea system is collapsing and people don’t believe the old stuff anymore. Then it’s important to clarify a new direction and why … Ideas can become very practical.

We believe in ideas here at GRITtv…. Speaking of which, Hurricane Sandy [caused devastation across many Eastern states and people are actively seeking ideas about how to rebuild and how to recover]. If you had your way, how would you do it? If you had a chance to model a community according to what you call a “checkerboard” of possibilities, how would you do it?

Checkerboard is interesting. There are some states where you can’t do much at all … and some states like much of New England and New York – you can do quite a lot. I would begin with all of the practical stuff that’s happening and say why don’t we do it all in one place. Why don’t we put in place a public bank, serious worker-owned co-ops linked together in the way that this Cleveland effort is (by the way, Cleveland efforts are all green, top of the line). I would get serious about working with the rest of the region. This is a big country and regions are going to be a big part of this. The Northeast is furthest along in trying to set up alternative structures. So those would be the elements: changing the ownership, putting in place a financial system, building a green structure and looking to regionalism and to models that are already on the ground. Simultaneously, you’ve got the ideas system. Let’s talk about the future in a different way … If we’re serious about this, it’s a process over decades, and what we have the chance to do in our lifetime is of laying down the groundwork, as the failures continue, of something transformative.

What’s hotel socialism?

Again, if you peek below the surface, many, many cities are in the business of owning hotels and public utilities. This is all public municipal socialism. The municipalities develop highly profitable land around highway exits or subways; they used to do the development and give the profits to the private sector and tax it back. They’re not doing that any more. The cities own it now and get the profits … Twenty five percent of American electricity is produced in co-ops and public utilities.

And the money goes back to public coffers?

Right back to the public. It’s socialism if you like. Real socialism, not what they claim Obama is doing. It’s actual ownership of the means of production.

What can people do if they say I don’t want to have that kind of responsibility over my workplace? I just want to go in, do my 9-5, be told what to do and leave?

Relax. People tend to think you’ve got to participate. That’s fine, too. That’s another way to deal with a very affluent system … People ought to have that choice. This country today, we do not have an economic problem. How can I say that? If you divided the current lousy economy up, it’s about $200,000 for every family of four today even in the horrible economic mess we’re in. We have a political problem of how to manage the richest economy in the world and that’s what we’re talking about – how do we change the power that controls that economy?

Can I take the $100,000 and work less hard?

You got it: Split the work week in half and you have a 20-hour work week!

Gar Alperovitz’s What Then Must We Do: Straight Talk About the Next American Revolution comes out this month from Chelsea Green.

This transcript courtesy of Truthout.

March 8, 2013

Trailer: The Next American Revolution

February 28, 2013

Going outside the hospital walls to improve health

This article was co-authored with David Zuckerman, and originally appeared in the Baltimore Sun.

Study after study demonstrates that poverty is a powerful driver of poor health. Many of America’s leading hospitals exist in poor communities. Could these powerful institutions (in economic as well as medical terms) help overcome the deeper sources of failing health among the 46 million Americans living in poverty?

A little-known provision of Obamacare provides an unexpected opening.

Section 9007 of the Affordable Care Act requires every nonprofit hospital to complete a Community Health Needs Assessment every three years to engage the local community on its general health problems and explain how the hospital intends to address them.

This means that nonprofit hospitals are no longer permitted to treat only those within their walls. They must now reach out to the community, especially its underserved populations.

Hospitals are major economic engines. Nationally, nonprofit hospitals alone had reported revenues of more than $650 billion and assets of $875 billion as of August 2012. If employed strategically, this powerful force could have a major impact on the health and well-being of people in poverty across the nation.

Several far-sighted institutions already offer a glimpse of what this can mean. University Hospitals and Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland — two leaders in the field — have decided that reducing health disparities requires such community-based economic strategies as bringing down high rates of unemployment, improving educational achievement, fostering community safety and building stronger social service networks. In 2007, these two hospitals and other community partners embarked on a comprehensive program to build community wealth.

The effort included employing their massive purchasing power to help develop a network of green, local worker-owned cooperative businesses to supply the area’s large nonprofits. Taxpayer funds supporting Cleveland’s nonprofit hospitals now do double duty by helping to underpin a broader community-building agenda, creating jobs and companies that — unlike corporations that come and go — will remain rooted in the local economy.

Among the cooperatively owned businesses are an ecologically advanced, commercial-scale laundry capable of handling 10 million pounds of health-care linen a year; a solar company that installs panels for the city’s largest nonprofit health, education, and municipal buildings; and the largest urban greenhouse in the United States, one capable of producing 3 million heads of lettuce and 300,000 pounds of herbs a year.

Each of these businesses also provides no-cost health insurance to employee-owners, improving health and building community at the same time. And more such efforts are in the planning stages. Hospitals and other “anchor institutions” spend $3 billion a year — not counting salaries and construction — in the 40,000-person urban Cleveland neighborhood where University Hospitals exists. (Hospitals in many other cities are considering strategies based on the Cleveland model, including Pittsburgh, Atlanta, and Washington, D.C.)

Indianapolis’ Community Health Network suggests additional possibilities. In 1996, the hospital discovered that area residents judged that safe and clean streets were central to creating a healthy community. The hospital system completely refocused its community benefit program and over the past 15 years has developed a comprehensive program aimed not only at street cleanups and safety but at improving family economic and food security. Community Health Network has supported a community supported agriculture program, a new food cooperative, efforts to rehabilitate local housing, and a matched-savings account program to help residents build assets.

Baltimore’s Bon Secours Health System provides still another powerful example. In the late 1990s, Bon Secours concluded that the leading community health priorities involved such nuts-and-bolts issues as getting rid of rats, cleaning up trash and providing affordable housing. Since then, Bon Secours, working in partnership with Southwest Baltimore residents, has developed more than 650 units of affordable housing and has cleaned up and converted more than 640 vacant lots into green spaces.

Pop culture lionizes the heroic doctor, saving patients through dramatic, last-minute surgery. This will always be a vital hospital role. But how many lives could be saved if hospitals were better at addressing the conditions that produce such health emergencies in the first place? The little-noticed Obamacare requirement may help us find out.

Gar Alperovitz, Lionel R. Bauman Professor of Political Economy at the University of Maryland and co-founder of the Democracy Collaborative, is the author of the forthcoming book “What Then Must We Do?” David Zuckerman (dave@democracycollaborative.org), a research associate at the Democracy Collaborative, is author of the report, “Hospitals Building Healthier Communities: Embracing the anchor mission.”

February 11, 2013

Interview with Elias Crim for Solidarity Hall: Living in the New “Pre-History”

This interview originally appeared on Solidarity Hall

To begin with, tell us about the Democracy Collaborative’s focus on community wealth-building. How can that be done?

We also use the term community-sustaining economy—and we’re interested in forms that build democracy, community and equity. In smaller companies, we know that worker ownership is a useful device. Indeed, we are strong supporters of worker coops and worker-owned companies in general. In large firms, worker ownership in some industries might produce different equity results. That is, the larger community has a stake in the impact of their operations. And we’ve been interested in how you can blend these different interests most successfully.

The problem with pure worker ownership of large industries is that the worker/owners are under the same market pressures as any other company. They are therefore as likely to pollute the environment, for example, if they’re under competitive pressures to do so, as the next guys. So that means the worker-owned company’s interests are somewhat different from that of its surrounding community—which includes elderly people, young people, all those who happen to be out of the workforce. After all, half the society at any one time is not part of that worker ownership.

So we think it’s critical, to use economists’ language, to begin to internalize the externalities through structures that reflect the broader community’s interests, rather than putting workers’ interests at odds with them. The Evergreen Cooperatives in Cleveland, for example, is a key initiative that reflects this worker-community model, and which we helped design.

Back during the Occupy protests a year or so ago, you published a NY Times op-ed on the quiet revolution in worker ownership that has been growing in recent years and yet has been little noticed.

Well, to start with, the national media doesn’t cover much at the local level—they don’t have the resources any more to do so and that’s getting worse, not better. So it’s not surprising that people don’t know about this development.

But part of what’s driving these experiments—in worker ownership, cooperatives, and other hybrid forms– is the fact that so much economic failure is occurring: an historical process is behind this. So there are now ten million Americans who are worker-owners at their companies—about three million more than there are members of private sector unions, in fact.

Some 130 million people now belong to a co-op or credit union. Neighborhood owned corporations number between four and five thousand. There are several thousand social enterprises, increasing numbers of B Corporations, growing numbers of city- or neighborhood-owned land trusts.

These new forms are often following functional lines. So that neighborhood ownership makes more sense for housing, for example.

Take the concept of municipal ownership which was favored when appropriate in its earlier days by the Chicago school of economics. There are around 2,000 municipally owned utilities around the country, with several new municipalizations in recent years.

There’s also the Cleveland model, which is being applied in other cities—again, largely and simply because the other business models are failing before everyone’s eyes, just as are traditional liberalism and traditional conservatism.

And more importantly, I think, people are now beginning to ask, where does this all lead to in our larger political-economic system?

You argue in your most recent book that reform is not enough. We need to change the very structure of wealth-holding institutions—by creating more public banks, for example. Is that happening?

Yes, the idea of public banking is making strides and is going to make more. And again, it’s because of the failures. The so-called Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act has been in effect for some time now. But instead of controlling the behavior of the big banks, they’ve only gotten bigger and are taking even bigger risks. The numbers here are quite extraordinary.

We want a model that begins with decentralization and the principles of community and with the recognition that creating local community requires stability. That means people anchored in a place where they can flourish, rather than being forced to move, as was the case with millions of residents of Detroit or Youngstown. Cleveland was once 900,000 in population; it’s now less than 400,000. How can you have democracy when people are totally uncertain about their economic future? So stability is required.

With regard to the financial system, you notice the big banks distanced themselves from local communities a long time ago. They’ve likewise gone in for dangerous levels of speculation, claiming that they’re more efficient thereby. This claim, even if it were true internally, is contradicted by the fact that they are extraordinarily wasteful in terms of the larger system problem here. They are capable of creating tens of trillions of dollars of losses when they fail.

In the earlier days of the Chicago School of economics, which I have considerable respect for because of its rigor and integrity in that period, they faced the fact that many big banks and indeed corporations were not supportive of communities. These economists—I’m speaking here of Henry Simons, Milton Friedman’s teacher and others—wrote important reports calling for nationalization in certain cases, on the principle that some firms could not be regulated. This group understood regulatory capture very well, realizing further that even if you broke these institutions up, they would simply find a way to regroup and be back at the same game again.

Interesting—so you’re saying the early Chicago school had a sense of human scale?

Absolutely. They began from the community. I would put it this way: if you can’t have democracy with a small D in the communities, you’ll never have democracy with a big D in the continental system. I think Henry Simons had exactly that view. I have differences with that school in more recent times but I think that on this front they had a very great deal to teach us.

The Evergreen Coops in Cleveland make reference to the Mondragon Cooperative Corporation in Spain, an enterprise that was founded by a Catholic priest on Catholic social principles. The Cleveland project is purely secular in nature but it seems to retain much of that spirit. Were you instrumental in bringing the Mondragon model to bear in Cleveland?

It’s an interesting tale. There are very powerful roots of cooperative thinking in Catholic social thought in general, leaving aside Mondragon. In some ways, however, we at the Democracy Collaborative had already been working on finding ways of using the procurement process at public institutions—hospitals and universities in particular—as a way to create and stabilize jobs that represented some form of worker or neighborhood or community ownership. All this was quite independent of Mondragon. It was only later in the project that we began to see things we could learn from Mondragon, such as how to implement a revolving fund in the various cooperative structures.

We were also interested in building a community-wide structure which is not a Mondragon idea, since it is not a community organization. MCC is a corporation, a group of cooperative enterprises.

In the U.K., the Cameron government was for a time promoting a vision of the Big Society as a way of regenerating local communities. One of the more visible proponents of this bottom-up vision of civic renewal was the social philosopher Phillip Blond. Any thoughts on this Big Society initiative?

I’m certainly aware of Blond and have a general sense of his work. When we think about community—and I have favorably quoted the work of Robert Nisbet also on this subject—we sometimes come up against the difficulty that when some groups pursue community-building, they tend to avoid the harder economic issues. I think that’s a real danger for some of communitarian thought, the tendency to leave to one side these important economic issues.

You’ve spoken and written about the importance of regionalism in regenerating our communities. Tell us a bit more about why this regional angle of approach matters.

There’s a great body of work on this subject, going back to the beginnings of the twentieth century and particularly around the 1930s. And the argument here is quite simple. Just consider the sheer size of this country, compared with the other developed nations in the Western world. It surprises people to learn that you could tuck Germany into the state of Montana or fit France comfortably within the state of Texas. The difference in scale is one of the reasons European politics are in a sense so much easier.

We, on the other hand, have some 315 million people spread out over 3.5 million square miles. We are headed toward 500 million people and thus the argument for decentralizing. If most states are too small and the continent itself is too large, what’s left –if democracy is to flourish–is the intermediate unit, the region.

I don’t know if you know the work of Alberto Alesina, an economist at Harvard who co-authored a book called The Size of Nations. He and his colleagues have been looking at the economic effects of scale, a topic which has not received much attention for decades. I wrote an op-ed piece for the New York Times several years ago on the possibility of California leading the way toward this kind of devolution and I explained why I thought it had to happen: as the only way to avoid the mounting inefficiencies, political and economical, which occur when states become too large. So I see recent developments tending to confirm regionalism from converging angles.

You mention that in a systemic crisis, not just new proposals but new thinking is needed—something we hope to do here with Solidarity Hall’s interactions. I think you might also in agree that crisis can create solidarity—is that fair to say?

Yes and I would add another factor: growing distrust of large institutions, especially in the areas of government and politics. There are two ways to think about new ideas. First, we certainly need them and I would agree with what you suggest in your question. But second, and I think more interestingly, these systemic failures are part of a historic process which itself is forcing us to realize the need for new ideas. The pain levels are getting quite high and the failures are great. I write books and articles and do research and so I’m very much in the business of ideas. But in fact I don’t think ideas matter much most of the time. Power and momentum matter.

But there are times when things are breaking down—and this is such a period—when ideas do matter and people are forced to think about things.

You have a new book coming out shortly. Please give us an idea of the subjects you’ll be taking up there.

Sure. The title is What Then Must We Do?, a phrase taken from Tolstoy. I suggest that traditional liberalism, traditional conservatism and traditional radicalism are now at a dead end. We are in a strange form of crisis which will neither end in societal collapse (as in the Marxist model) nor success (as in the liberal model) nor in some conservative model. Instead we’re caught in a never-never land of sustained stagnation and decay—which I argue is a very unusual societal context, being neither reform nor collapse. I think we’ve been in this context for some time now.

Amidst the pain, this situation has one advantage. Since we don’t appear to be headed toward dramatic change in any direction, we do appear to have time to think. And thus all these new initiatives we’ve been discussing here—a whole rich, new debate has started up in this country.

Moreover, as I argue in the book, we are potentially in the pre-history of truly fundamental change, beyond traditional corporate capitalism, beyond state socialism. So all this experimentation is very important and it could be laying the foundations of something for the long-term.

If America is, as it’s sometimes called, a laboratory of democracy, then some of these principles, even at a small stage in local “laboratories,” can eventually be applied at other levels. This is the kind of important groundwork that was done prior to the New Deal, prior to women getting the vote, prior to the Progressive Era itself.

January 23, 2013

Ownership, Full Employment and Community Economic Stability

This article originally appeared as a guest post on Robert Pollin’s “Back to Full Employment” blog.

The great British economist the late Joan Robinson once observed that the only thing worse than being exploited by capitalism is not being exploited by capitalism. This truth is felt acutely by anyone who is unemployed and looking for work. As the pain of the economic crisis continues and millions struggle to find employment there is an obvious imperative to create jobs—any jobs. But we shouldn’t stop there. In Back to Full Employment, Robert Pollin makes the essential point that “a workable definition of full employment should refer to an abundance of decent jobs.” Poor jobs that keep workers minimally employed but leave them in precarious circumstances and unable to participate fully in civic and political life are better than no jobs at all. But in terms of public policy we can and should aim higher—especially as decent jobs not only benefit the workers that hold them but also the communities in which they live. Absent a stable economic base, community itself is compromised.

Three elements of the instability challenge lend critical perspective to the issue. The first can be seen in the long-term results of the decline of manufacturing industry in the rust belt. We have in fact been quite literally “throwing away” entire cities—cities like Cleveland, Detroit and St. Louis. Since 1950, Cleveland and St. Louis have each lost half a million people, drops of more than 50 and 60 percent respectively; in Detroit, the fall in numbers has topped a million, more than 60 percent. The uncontrolled corporate decision-making that results in the elimination of jobs in one community—leaving behind empty houses, half-empty schools, roads, hospitals, public buildings, and so forth—implicitly requires that they be rebuilt in a different location. Quite apart from the human costs involved, the process is extremely costly in terms of capital and also of carbon content—and at a time when EPA studies show that greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activity in the United States are still moving in the wrong direction (having jumped by over 3 percent between 2009 and 2010 alone).

A second aspect relates to democracy. Substantial local economic stability is clearly necessary if democratic decision-making is a priority. A local population tossed hither and yon by uncontrolled economic forces is unable to exercise any serious interest in the long-term health of the community. To the extent local budgets are put under severe stress by instability, local community decision-making (as political scientist Paul E. Peterson has shown) is so financially constrained as to make a mockery of democratic process. This becomes still more problematic if we recognize—as theorists from Alexis de Tocqueville and John Stuart Mill to Benjamin Barber, Jane Mansbridge, and Stephen Elkin have argued—that an authentic experience of local democratic practice is also absolutely essential for there to be genuine national democratic practice.

Thirdly, and straightforwardly, it will be impossible to do serious local “sustainability planning”—mass transit, high-density housing, and so forth—that reduces a community’s carbon footprint if such planning is disrupted and destabilized by economic turmoil.

So yes, we need jobs. And yes, we need good jobs. But we also need an approach to good jobs that will allow us to grapple with the challenges indicated above while at the same time begin tackling the grotesque maldistribution of wealth in this country—a distribution that has reached literally medieval proportions. The top 400 individuals now control as much wealth as the bottom 180 million Americans taken together.

How to go about all this? As we—hopefully—begin to adopt smarter public policies aimed at reaching full employment, we should maximize the impact of these policies by choosing strategies likely to economically stabilize our cities and regions. A decent job should be understood as one which not only pays well, but which is anchored in a community, and which in turn anchors a worker and participant in the civic life of that community. If the culprit behind economic destabilization, and its catastrophic effects in terms of employment, is capital mobility, the solution will require increasing the proportion of capital held by actors with a long-term commitment to a given locality or region.

The problem, however, is that major footloose corporations are not only able but willing to jump from one city to another as they chase “incentives”—and mayors and governors waste taxpayer dollars in endless bidding wars. This raises the question of alternative ownership forms (something Pollin also began to take up in a 2012 article in the Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society). By rooting ownership broadly in the community, jobs stay put. And jobs that stay put create more jobs, through the multiplier effect of money circulating within a community as well as by expanding the tax base of cash-strapped local governments.

Worker and community ownership—whether through employee stock ownership plans or more egalitarian or community strategies—are forms of ownership relevant to thinking about jobs, job creation, and local economic stability. Crucially, community or cooperative ownership of jobs appears all but certain to yield more stable long-term employment than traditional corporate strategies, and is thus more valuable as part of a package of policies aimed at full employment. Companies owned by people who live in the community rarely if ever get up and move.

Traditional employers also have an incentive to keep labor costs low and will use workers only for as long as they are needed on a particular job. A number of community enterprises now aim to maximize employment over the long term. Instead of treating employees as disposable, such employers seek ways to find new work for their workforce or share existing work. (The BBC recently provided a striking example of this in their coverage of the resilience of the Basque country’s Mondragón cooperatives. In the regions where Mondragón has a significant presence, the unemployment rate is around half that of the rest of Spain.)

Worker ownership works in the US, as well. It’s not often realized that there are over 10 million Americans who work at jobs they also own—more than are members of unions in the private sector. In Cleveland an innovative complex of worker owned cooperatives, linked through a revolving fund and a non-profit corporation—and in part supported by procurement from non-profit hospitals and universities—has become a model for several other community efforts. A large part of this recent boom in worker ownership is due to federal policy; specifically, legislation that created substantial tax advantages for business owners who sell their ownership stake to their workers.

Another example of how smart policy has been used to cost-effectively support a worker-ownership job retention strategy can be found in the Ohio Employee Ownership Center (OEOC). The OEOC has used a relatively modest amount of state and federal funding (less than $1 million annually) to facilitate worker takeovers of firms whose owners are retiring or that are threatened with closure. Such firms, owned by workers, are city (and tax base) stabilizers: they do not get up and move. The OEOC has created enormous economic returns—retaining jobs at a cost of less than $800 per job and helping stabilize thousands of jobs in Ohio cities. This is in sharp contrast to traditional economic subsidies aimed at job retention, which cost far more, deliver less, and often lead to a destructive—and destabilizing—subsidy arms-race between different cities and states.

How might we begin, on a national level, to build a strategy to mobilize worker and community ownership as a means of reaching full employment? One policy intervention that could go a long way intersects with another of Robert Pollin’s concerns in Back to Full Employment. He notes that while successive rounds of economic stimulus have kept interest rates low, they have not always succeeded in making credit available to small businesses. Small worker owned businesses could benefit from policies that specifically expanded their access to credit. (In addition to the general reticence around lending Pollin highlights, these kinds of projects, especially cooperatives, have to deal with lending institutions that are often unfamiliar with or even hostile to democratized enterprises.)