Ruth Knafo Setton's Blog, page 4

November 13, 2014

RIO'S BLACK HEART

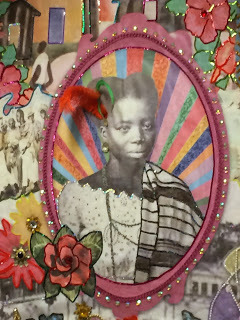

Tia Ciata

I entered this city through its music, and with every step I hear the sounds of a tradition so rich and powerful the roots spread across the Atlantic Ocean from the coasts of Africa to Brazil, and then ricocheted back to Europe and the States, where it influenced generations of musicians … and one 15 year-old girl who sat in a movie theatre, watching the classic film by Claude Lelouche, A Man and a Woman, for the third time—not just for the love story, but for the song Pierre Barouh sings to Anouk Aimee as he climbs stairs behind her swaying hips and lovely face as she turns back to smile at him. He sings the words of Samba Saravah, by Brazilian songwriter, Vinicius de Moraes, an ode to the female heart of samba: “She came from Bahia, centuries of dancing and sorrow … and though she may be white in form, she is black in her heart.”

That year I’d gone to Paris for the first time, where someone informed me that as a Moroccan-born Jew, I was considered a pieds noir—someone with black feet. It was clearly not meant as a compliment, but I took it as one. I have black feet, I thought—wow, that means I am part of that vast African continent—and in that theatre, where the projectionist ran the film for only me, I added a black heart to the mix.

Years later, I stand on the notorious Pedra do Sal (Rock of Salt) in Pequena Africa (Little Africa), near the Empress Wharf where slaves from Africa were unloaded, and not far from the square (now a park) where they were bought and sold. Today, the Rock is hushed. A woman carrying groceries climbs past me, two boys sit and play with their dog.

The sun is bright as I climb the stone steps carved by slaves to make it easier to carry salt. The ocean is minutes away, and behind the dust I smell the sea breeze. During Carnaval the port will be crammed with cruise ships, but today—November 7th—our ship is the only one docked in the harbor. We sailed from Morocco—the northwest corner of Africa—to Barcelona, and then a fourteen-day crossing to Rio, echoing the Middle Passage—the heart-wrenching transportation of slaves from the coasts of Africa to Brazil and Barbados. Brazil received four million slaves, more than the United States—a fact that surprised me. Generations of slaves kept coming, keeping the African traditions alive, until slavery finally ended in 1888.

Walls surrounding the Rock are covered with graffiti—dancing figures, balloons and cryptic symbols, a stenciled black model with an Afro, and a message: “If you don’t think she’s beautiful, then you need to free yourself from your preconceptions,” and slogans like “Zumbi Vive” indicating that the spirit of Zumbi, one of the first heroes of slave rebellions, is still alive. And if there’s anywhere to feel the spirit of hope and freedom, it’s here on the Rock, and if there’s anyone to thank, it’s Tia Ciata, the woman whose house I face.

Her full name was Hilaria Batista de Almeida, but she became known as Tia Ciata. Never a slave, she was one of the Bahian aunties—the African women who moved to Rio de Janeiro at the turn of the 20thcentury and brought with them centuries of traditions, including knowledge of the healing powers of Candomble, the African-based religion that relies heavily on percussion and movement as well as communication with orixas—saints and gods. Slave owners banned both Candomble and samba, and the dangerous, subversive merging of infectious rhythms, wild dancing and chanting that led to trances.

But there was one place in Rio where Afro-Brazilians—whether they were free, slaves, or slave-owners themselves—could dance all night to the pounding of drums and clash of tambourines: Tia Ciata’s house.

A century after Tia Ciata opened her door to samba, her door is closed, but it’s easy to imagine the Rock still jumping. Tonight there will be live samba. Turn a corner in Rio and you’re likely to find a band or singer and his guitar, crooning samba in one of its many variations.

with our lovely chef who made us feijoada at the Samba Warehouse

with our lovely chef who made us feijoada at the Samba Warehouse

my students & I in Carnaval costumes

Earlier today I took my students to the Samba Warehouse, where Akiva Potasman took us for a lively percussion workshop and for a tour of his Samba School’s workshop—the lush wonder of costumes and floats in process as they prepare for next year’s Carnaval. The importance of samba & Carnaval is impossible to exaggerate in the lives of those involved—students rehearse 3 days a week, 4 hours at a time, and must find their transportation to and from the school space, often traveling an hour each way. There are about 5,000 students in each “school,” and there are 12 schools in Rio. They create, rehearse, work, dream, and prepare for the 2 days of Carnaval-- an opera under the stars, magical realism at its most intense. And only1 school will be lucky enough to win.

The following day I return to the Pedra do Sal, and it feels like I’m coming home. To quote Vinicius de Moraes again, “Singing a samba without sadness is like loving a woman who is only beautiful.”

I think of the dedication that drives the students of Samba and Carnaval to create beauty over centuries of pain.

The heavy, sultry voice of Ito Melodia at the gorgeous club, Rio Scentarium, in Lapa.

The blues—another form of music carried from Africa and whipped into raging life by generations of slavery. It is raw and harsh and crooning and direct and it hurts so good. Like samba, it is the kind of sadness that transforms into joy, that gives birth to hope. It’s survival music that seizes you by the throat and won’t let go.

block party in one of my favorite neighborhoods, Conceicao

So I stand on the Rock, waiting for Tia Ciata to open her door. It is a sunny, quiet afternoon, but I hear sounds of percussion and feet tapping, voices singing, and see hips swaying and heads thrown back. And I feel saudade—that wonderful untranslatable word that means nostalgia and longing for what you’ve left behind, what can never be recaptured, and even nostalgia for the future. I feel saudade for this me in this city at this moment … even as it slips away and I look back over my shoulder at the Rock of Salt and sea wind blows me away from Rio.

Tenho saudade de voce, Rio.

Published on November 13, 2014 09:23

November 6, 2014

Barcelona: Turn Left at the 19th Century

La Boqueria

Barcelona blows me a kiss … from a balcony overlooking Las Ramblas. Her white dress flies up, just like Marilyn Monroe’s in The Seven Year Itch, but her platinum-blonde wig doesn’t lift a hair.

“She’s a he,” says my quirky guide, Albert.

Of course she is. What better place for a female impersonator to pose than perched on a balcony over the street that embodies living theatre, a street so vast and crowded that each section has its own distinct character—so many little “ramblas” that it became known as Las Ramblas rather than the singular La Rambla.

Barcelona cries, “Eat me! Drink me! … How can I refuse the invitation to enter La Boqueria, the market to end all markets? Fruits and vegetables plump and gleaming, begging to be touched, rows of brilliant colored fresh-squeezed juices and plastic cups heaped with fruits. Pyramids of candies—chocolates, jellies, marzipan fruits, cocoa-dusted nuts—a cornucopia of sweets bursting open. Vast slabs of meat sway over stands, fish and unrecognizable sea creatures seem to wriggle on counters. Locals stride directly to the stand they want while tourists wander in a dazzle of colors, smells, textures gone wild.

So hard to choose …. How about a Torre—a traditional Catalan sweet made of almonds and served in winter? Or a slice of moist date-nut bread? A hunk of pale, sharp cheese? And then I see a cup crammed to the top with large pieces of one fruit: the deep, rich yellow-orange of ripe mango.

I hold out my hand to buy it and manage to move two steps away from the fruit stand before spearing the first mango triangle. Sweet and ripe, the taste explodes on my tongue.

Barcelona calls to me in Catalan … that ancient tongue, from storefronts and cafes, and walls and balconies, where her flag—the deep yellow of ripe mango, with four red stripes that according to legend are four fingers dipped in blood. At one end of the flag is a white star against a blue background.

Albert, who was born and raised in Barcelona, and has the fierce pride of his Catalan heritage, explains that the people who hang these flags are signaling that on November 9th, they will fight for the referendum that will determine the Catalan state’s right to vote. A human chain of nearly two million people, from the Pyrenees to Valencia, formed an enormous V for Vote.

Will it happen? The election is only a few days away. Locals I spoke to were doubtful, but fervent about the need to try. One said, “Even though Catalonia is the most economically successful state of Spain, the government wants to retain control over us and bind us to ancient laws. The question is: do we need them?”

“We Catalans were always the rebels,” says Albert with a wry grin. “The thorn in the government’s side. We are not fighters, but we know how to talk and write, and really, that’s why we are joining hands—to fight for our voices to be heard.”

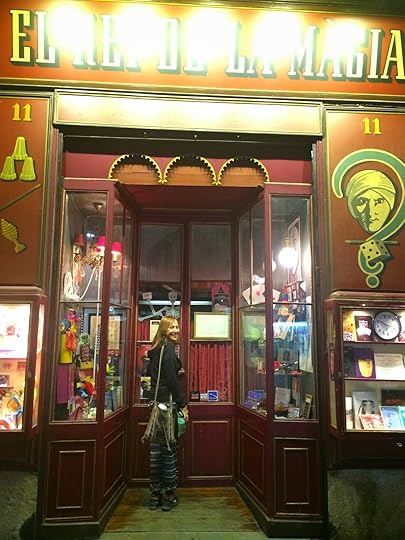

Barcelona whispers in my ear … orange-scented murmurs of the true Barcelona, rumors of hidden places known only to its longtime inhabitants, secret places that may or may not exist in daylight, but that are there all the same, if you only have the eyes to see them, and if the light is just right. I listen to the wind and crooning voices and learn about a walled garden behind a bookstore in Portal de l’Angel … a flamenco bar near Placa Real, where at midnight dancers throughout the city congregate to perform for each other, and woe to you if you applaud because the performance is not meant for you … a speakeasy with no sign, where you knock on a faded door and the bouncer looks out and decides if you are worthy to enter … and a magic shop, the oldest in the city, with a multitude of tricks and illusions, and a curtained backroom, where the true magic happens.

The directions are purposefully vague: turn left at the second cobbled street behind the large café, walk until you see a stone wall, then turn right down that alley. After a few steps, you’ll be there.

There? Where? I search, but see no sign of garden, bar or shop hidden from the public eye. I decide there must be a secret password, an Open Sesame that dissolves the gleaming contemporary facades of the usual suspects—Hard Rock Café, H&M, Zara, and multiplying Desiguals, sometimes four in a single block—to reveal the city’s pulsing heart.

Maybe I’m searching at the wrong time.

Maybe I don't have the eyes to see them.

Barcelona feeds me … and teaches me to nibble. Tapas and montevidos—small meals of fried potatoes topped with spicy Aoli sauce, cheese and meat sliced thin, and my favorite—the simplest of all: a ripe tomato rubbed against the crust of a bread, then drizzled with olive oil, sea salt, and a touch of garlic. All passed down with cold golden beer. I bite into pinchos at the Basque restaurant, Euskal Etxca, near the Picasso Museum —sublime tiny sandwiches pierced with toothpicks. When you are ready to pay, the waiter counts the toothpicks. “The honor system,” says Albert. And I drink orxata, a traditional drink made from roots, dense and chalky, yet surprisingly refreshing.

Barcelona paints my portrait … Picasso draws over my eyes—one jarringly large, the other smaller—the better to squint with, querida. Miro punctuates my mouth with dots and lines to turn my smile playful. Dali curls a deliciously malicious mustache over my lips. The three of them divide my face into cubes and sharp angles so it looks different from every perspective.

I peer into the window of an H&M and squint.

“Do you recognize yourself, querida?”

Actually, I do. I’ve just never seen all these sides of me at the same time.

Dali pulls me by the hand. “Now to Gaudi!”

With the others on our heels, we hurry to La Sagrada Familia and enter the vast cathedral that is Gaudi’s unfinished masterpiece. Gaudi elongates my neck a la Alice in Wonderland until I rise high enough to climb the tree-spiraling columns and touch the ceiling leaves and brush my fingers against the filmy fairy tale spires. I could swear I’m in a surreal airy forest surrounded by fresh green, a carpet of leaves far below.

Gaudi presses his large hand on my head. “There is a misunderstanding that an abundance of light is a positive element. That is not so. The light should be just right—neither too much nor too little—since both things blind, and the blind cannot see.” He releases me suddenly, and I float like a sagging balloon to the earth.

I leave the illuminated forest of La Sagrada Familia, and feel someone watching me. I squint back over my shoulder.

There they are, in a circle of light: Picasso, Miro, Dali. Soberly dressed in black, studying me—my cubes and lines, my playful dots and crooked eyes, my improbable mustache.

“Well?” I ask.

Picasso and Miro look at their shoes. I am embarrassed. “Thank you!” I call. “Gracias!” And add, “Gracies,” in Catalan, for good luck.

Dali twirls his mustache in farewell.

I twirl mine, too, and return to Las Ramblas, taking my time. Soon it will be the Magic Hour. Twilight—between day and night, the hour when sun and moon share the sky, and the light is just right.

Published on November 06, 2014 00:55

October 19, 2014

ITALY: BALCONIES, RUINS, & OPERA

ITALY: BALCONIES, RUINS, & OPERA

Did I tell you I love cities with balconies?

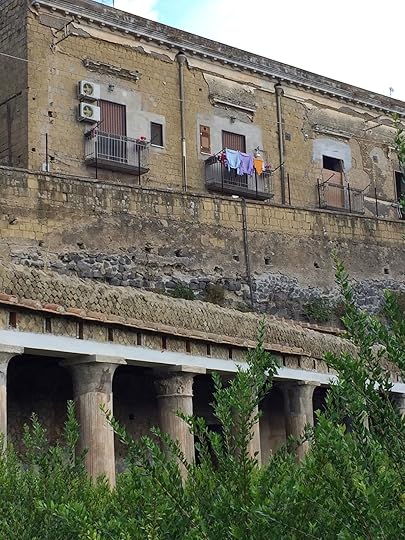

Lisbon’s wrought-iron balconies that remind me of the French Quarter in New Orleans … Seville’s “kissing balconies” in the old Jewish Quarter …. Actually the Jews brought balconies with them from Andalusia to Morocco, where traditional Arab houses turned inward, facing an inner garden courtyard known as a riad. Jewish houses faced outwards, with balconies that overlooked the sea, the street, & even cemeteries. A means of protection allowing the inhabitants to see the external world? Or a means of merging the inner & outer worlds? Whichever it is, I love them. And I am in Naples—oh, Naples, the Queen of Balconies—always crammed with laundry, brilliant shirts, faded jeans, towels & sheets swaying against gray sky & balmy sea air.

My first view: from a balcony in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, whose wide windows open onto gardens & courtyards, streets & buildings. The dark, dazzling panorama of the city is as fascinating & breathtaking as the incredible art inside its seemingly endless rooms. I move from the exquisite embarrassment of the Pompeiian baker Terentius Nero & his wife frozen forever in a painted fresco to a balcony where three American students pose for selfies—no embarrassment here—& car horns blare, tires screech, TVs blast, & a man sings opera at the top of his lungs.

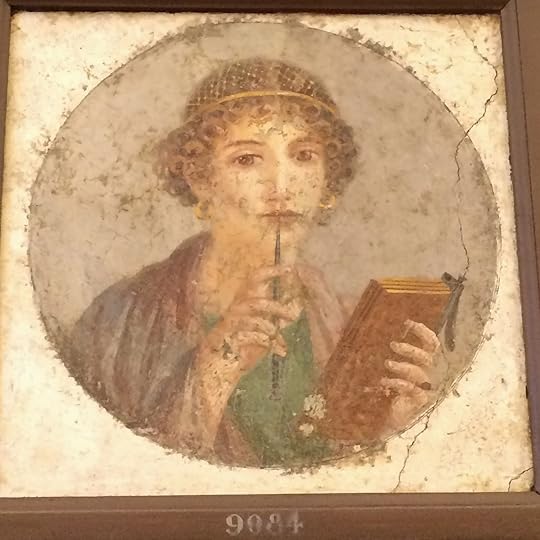

I return inside the museum to the Sappho, the wonderfully ageless portrait of a woman pausing in thought as she writes ...

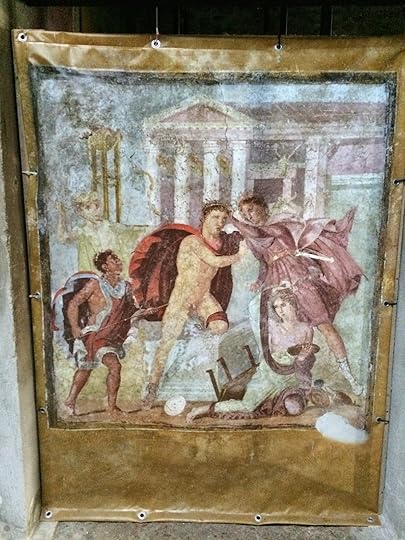

... & to room after room of frescoes, statues, wall panels, & artifacts taken from the houses of Pompeii & Herculaneum, two cities destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. Tomorrow I will go to Pompeii & wander the ancient city from one end to the other, moving in diagonals & half-moons like the Teatro, until the sky turns pink, an evening breeze blows, & only a handful of guards & tourists remain.

I stride over large lava blocks of the street & leap onto the high sidewalks as if I live here. I enter the villa of Marcus Lucretius Fronto—possibly the most beautiful house in Pompeii—with its frescoes as bright & vivid as if they were painted yesterday.

House after house decorated with haunting frescoes of animals, nature, people, gods & goddesses. Where did the painter get that blue, a blue so intense it reminds me of Moroccan doors? And the delicacy to paint an angel’s glittering, translucent wings? And how did it feel to live surrounded by such glorious art? I pass the fuller’s establishment—the laundry of Stephanus—where he washed clothes in stone tubs that were liberally laced with urine to treat the cloth. I wrinkle my nose as if I can still smell it, & I remember overhearing a woman in Naples complain, “It’s so smelly, loud, & dirty here. How can they hang clothes in such filthy air?”

Napolitanos are no strangers to strong smells, & neither were the ancient Pompeiians—they may not have eaten pizza with strong cheeses, but the sea swept nearly to the Porta Marina, they seasoned their food with garum, a pungent fish paste, & horses, donkeys, & people relieved themselves on the street. There was no sewage, & water flowed down the city toward the southern gate. There were wonderful smells too—of fresh bread baking, take-out joints serving hot food, incense & perfumes.

On another balcony of the Naples Archaeological Museum, I stand next to a guard (smoking) & stare at the city below—crammed with people, like its buses, trains & clubs. Colors, sounds, smells so vivid & raw they jolt you awake. Even the odd-shaped sharp black stones on the ancient streets force you to pay attention or you’ll stumble. This city is bursting with energy like a black sun. Rays reach toward you to draw you inside. Whether it’s balconies or storefronts or voices & hands, the city invites you to enter & become a part of it.

Back inside the museum to the ancient art, the richly decorated panels that adorned the houses of Pompeii. A couple sits on the floor & kisses in front of an enormous fresco. They are exactly right, I think, to respond to the pleasure Pompeii’s artists took in celebrating the body & erotic delight. Even my favorite statue of the goddess Isis is softly sensual & curved, utterly female in her power. Later, at her Temple in Pompeii, I will think about how the ancient world whispers to us when we live in its shadows. If we listen, we can learn so much—not only about how they lived, but about how we live … & how we can live better.

Tomorrow I will go to Herculaneum, Pompeii’s little sister, & the instant I enter, I feel a sharp pain, a blow to the gut. Tears burn my eyes. The town is so small & homey, almost intimate after the grandeur of Pompeii. It is divided into little blocks, houses, shops, corners & gardens. Vesuvius looms overhead, cloaked in clouds, & the modern town coexists peacefully with the ancient one at its feet like a slumbering cat. Laundry, of course, hangs from balconies. A man sings opera (that’s three times in three days I hear a man singing opera!), the passionate drama in his voice perfect for this place, this moment.

In Herculaneum I have no guide, no book, only my instincts to lead me. I am alone & I wander down streets until I find a peaceful corner in a “backyard” of a house, & climb up a small stone staircase. I sit for a while & imagine the people of the house eating, washing, praying, dreaming, touching, kissing ….

I am a slave girl hiding in the kitchen garden. I hear footsteps, low voices. Someone is coming. They know I’m here, & I need to get back to work before I’m punished. But the voices fade, the steps recede, & I’m alone again. Were the voices from then, or now? For a moment I wonder if I am from then, or now. When I climb down my staircase & step back onto the street, what will I find?

Maybe then and now have merged, like the balcony & the inner heart of the house it protects, like the sleeves of shirts waving from the railings-- arms beckoning.

Maybe I live here too, in one of the apartments overlooking the ancient town. I take down the clothes I hung to dry & breathe them in. They smell faintly sweet, covered with a fine layer of dust that clings no matter how hard I shake them.

From the next balcony a man clears his throat, preparing to break into song.

From a small stone staircase far below, so far away I barely glimpse her, a woman smiles & waves at me.

After a long long moment I wave back.

Published on October 19, 2014 22:21

October 13, 2014

HOW TO BARGAIN IN MOROCCO

RUTH’S 7 TIPS ON HOW TO BARGAIN IN MOROCCO

My father, may he rest in peace, was one of the great bargainers—an artist who entered a shop in the medina of Marrakesh or Fez, fixed on an object he wanted, & through a winding path of cajolery, teasing, charm & humor, walked out with the object … & a new friend, the vendor. Granted, my father was born in Morocco, spoke Arabic fluently, & was familiar with the ancient tradition of bargaining, but other Moroccans I watched didn’t do it nearly as well.

After carefully observing him, trying my own hand at it, & watching both experts & absolute duds, I humbly present my suggestions on how to get the most out of the bargaining experience.

RUTH’S 7 TIPS ON HOW TO BARGAIN IN MOROCCO

ENTER the medina (the market, the souk) the way you enter a casino. You know the odds are in the House's favor, & you know that eventually they will win, but you can have a wonderful time playing the game.

GAME is on. As a Westerner, you are at a disadvantage: you don’t speak the language (Give yourself 20 points if you speak French or Arabic), you don’t know the rules, & you are playing against the masters, & you’ll never know if you won or lost.

UNDERSTAND: price is a relative concept. There is a price for Moroccans, another for those who speak French, one for European tourists & another for Americans, one for students, & even, I'm convinced, one for blondes. There is a price if you appear interested, & another if they sense you’re wasting their time. There is a price if you charm them by getting into the spirit of the game, & another if you reveal actual knowledge about the object you want to buy. There is a price if you joke & another if you are sullen & act as if bargaining is beneath your human dignity.

YOU will never know what the item originally cost. The vendor himself has probably forgotten the original price, if indeed there ever was one. The mythical price he quotes at the beginning of the transaction is pulled from the sky, a magical number to start the game.

KNOW that what you pay has nothing to do with the cost of the object & everything to do with #3: who you are, how you present yourself, the experience of the game. I overheard a vendor exclaim to another—after a round of haggling with an American man that turned bitter & dark, even though the American capitulated & bought the item—“That was a bad one.”

THEY have been doing this for thousands of years. You are entering their world of labyrinthine corridors, dim booths shadowed by carpets, mysterious doors & archways that lead to dark alleys. In their world, bargaining is an art that involves laughter, warmth & personal connection, & often, a glass of sweet mint tea.

ENJOY the game. Carry your prize object out of the medina with a smile. Don’t compare prices at other booths. You carry not only an object, but a story, an experience. For a few moments, under North African sun or moon, you were part of an ancient tradition. Treasure that memory. It has no price.

Published on October 13, 2014 23:06

October 8, 2014

LISBON: YOU ARE ALREADY HERE

As you set out for Ithaka

hope the voyage is a long one,

full of adventure, full of discovery.

“You don’t need to travel to Ithaka,” says the handsome young man at the elegant stained glass window tea room/hotel in Alfama, the now-trendy, ancient stone & cobbled neighborhood of Lisbon. “You are already here, in Lisboa, the most beautiful city in the world.”

“What should I see?” I ask.

“Go out & wander. Lisboa is a city for walking,” he says, echoing my Portuguese friend, Mafalda, who suggested places to see & things to do, but insisted that in Alfama, “You should just wander.”

Lisbon is like a city in a dream—you turn a corner & have no idea where you’ll find yourself. A narrow, shabby street in which every building is covered with graffiti opens onto a vast sunny marble square lined with columns & cafes. A set of impossibly steep stone steps leads to an ancient cathedral. Winding cobbled streets, tiled Moorish archways, shadowy stone corridors & courtyards bump against weighty stone castles & fortresses. Laundry hangs from balconies—a pair of harem pants swaying in front of a doorway beckons me into a shop where I learn they belong to the upstairs neighbor. Over another shop, a man sits on his balcony, plays his guitar & sings. I realize that I love cities with balconies—they merge the inside & the outside, & invite the passerby into the street drama.

Like fado, this city doesn’t cover its dark heart—it displays it proudly. Fado is the music of the marginalized, the cry of the oppressed, the song of the yearning soul. Last night I went with my friend, Ricki, to Sr. Vinho, a fado restaurant. There were four performers—three women & one man—accompanied by two guitarists. The lights dim for a fifteen-minute set by one singer followed by a breather to eat, talk, drink, & then the next singer. The show begins at 9:30 & ends at about midnight.

My favorite singer is Liliana Silva. She tightens her fingers around the edges of her shawl & throws her head back to unleash her song. As personal & intimate as the balconies nearly touching across narrow streets, fado also seeks to connect. It means “fate” or “destiny,” & the emotion in Liliana’s powerful voice & the eloquence of her gestures & expressions transcend language barriers.

Fado is the expression of saudade, one of those wonderful words that means so much more than its definition. Saudade is a longing for what you’ve lost, nostalgia for the home you left behind, pain at the loss of yesterday, & yearning for what can never be recaptured.

The Portuguese understand saudade—their heads turned back like Lot’s wife—while they squint into the horizon for the coastline glimmering in the distance, a mirage from the future. Vasco da Gama & many other Portuguese sailors left their homes in search of new lands to conquer.

“We are never satisfied,” says the young man at the tea room in Alfama. “Like Fernando Pessoa, we want many lives, many identities. We want a chance to fail at all of them.”

“Is there any city that cultivates sadness more lovingly than Lisbon? Even the stars only ‘feign light’,” wrote Pessoa.

Pessoa—which means “person”—is the resident artist spirit who haunts Lisbon. He was raised in South Africa, but returned as an adult to Lisbon, which he never left. He worked at a series of accountant jobs while trying his hand at publishing & translating. A prolific writer, he wrote not only under his own name, but under 75 others, which he called “heteronyms,” each with his own independent intellectual life. He is everyone, & he is no one, & when you walk in Lisbon—as he did, ceaselessly—you might glimpse a short bespectacled hunched figure a few steps ahead.

You walk faster to see if it can possibly be … of course not, it can’t be … he died in 1935…

Yet …

… this is Lisbon after all, the city that exists in the between—yesterday & tomorrow, darkness & light, poverty & opulence, barbarity & kindness, the journey & the destination. “To dream about Bordeaux is not only better but also truer than stepping out of the train in Bordeaux,” wrote Pessoa.

You stop rushing & look around you in wonder. After all, you are already here, exactly where you are meant to be.

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her you would not have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

--Cavafy

Published on October 08, 2014 14:38

October 3, 2014

IRELAND: IN SEARCH OF THE GODDESS

[image error]

I hear the call in the deep heart’s core. --Yeats

I heard it across the seas in the rustling forest near my home in Pennsylvania, & I heard it in the sound of the waves, & I heard it the instant we docked in the port of gritty & raw Dublin, one of my favorite cities in the world. I’ve only been here once before, for a wonderful Thanksgiving week with my son Avi, but it was enough to make me want to return. What I remember: the words of James Joyce across the window of the Guinness Storehouse as you survey Dublin over a foaming pint, the musty welcoming smell of old books in the Long Library at Trinity College, the forty shades of green in the parks, the rich, dark coffee, & the sweet sharpness of the language. Whether the Irish speak Gaelic or English, whether they’re joking or telling tales, there’s music to the words, a cadence & rhythm that invokes & evokes the soul’s mysteries the way poetry does. It’s a code to decipher & puzzle over. Letters take on new identities, others are present but silent, while others are heard but not seen. Niamh = Neve. Sidhe = She. The words curve like fingers & beckon into the woods, whisper the divine call of the Sidhe, those mischievous faeries: Away, come away (said Yeats, who heard them, too).

And then they leave us in the woods, our hearts tied in a Celtic knot, our eyes staring wistfully.

I hear the call as I leave the dock with my friend & Semester at Sea colleague, photographer Todd Forsgren. We head in search of the sacred feminine, & the first thing we see is a small statue of Mary guarding the sailors, & those who have sinned.

I hear it stronger inside the crypt of Newgrange, the Neolithic passage tomb, with its prophetically accurate Roof Box, a carved opening that lets in the sun during the Winter Solstice—perhaps the world’s first solarium. I lift my head to the vaulted carbelled roof, layer upon layer of scalloped, fitted rock that reportedly hasn’t leaked a drop of water (in rainy Ireland) in 5,000 years, & gaze at the mystical symbols—tri-spirals, diamonds & zigzags—carved into the recesses. The guard—an irreverent man with a metallic-gray Elvis pompadour & a side-creeping smile—turns off the light & says, “Imagine the Sun God penetrating the Earth Goddess to make the earth fertile.” A dazzling ray of light filters through the Roof Box & lights the crypt. I know I’m not the only one who shivers. It’s very sexual, very Demeter, & very powerful. I’m especially moved when I learn that the 92 massive rocks that circle the round tomb of Newgrange are carved with the same mysterious symbols as Howth (the neighboring passage tomb), but unlike Howth, where the rock carvings face outwards as if to protect those inside from invaders—at Newgrange, the carved symbols face inward, like magic amulets pressed to your heart.

I hear it deeper inside my heart as we enter Kildare, a medieval town dominated by St. Brigid’s Cathedral on one side of the town square. Cill = Church. Dara = Oak. Apparently Brigid, who was a real person before she became a legend—saint, goddess & witch—was beautiful & headstrong, & wandered the country in search of a place to set up her church. She found it here, in an oak ridge & set out her magically expanding cloak to mark the dimensions of the land. She built the first monastery in Ireland, & curiously one where monks & nuns cohabited (separately, but under the same roof). She was the Abbess, but so powerful she was known as a Bishop.

Inside the cathedral, which is as musty as the Long Library, we hear a persistent humming. Is that the call? Todd & I walk from one altar to another, surrounded by dark, damp stone, searching for the source of the humming. Is someone confessing in a hidden alcove? Is the cathedral haunted? The mystery is cleared up when we walk outside & wander the grounds. A weed whacker! An absurd prosaic detail that reminds me of exiting the sacred mysterious crypt of Newgrange to see a pasture of dozing cows a few feet away. The sacred & the profane rub shoulders in Ireland.

Behind the cathedral is a Fire Pit where Brigid started a fire that burned without ashes for centuries. It was tended by nineteen nuns. Every night the nuns chanted, “Brigid, take care of your own fire for this night belongs to you,” & in the morning, the fire would still burn bright. Brigid died in the year 525, but the fire burned on until a priest magically put out the flames. And that was the end of the fire.

I visit the Fire Pit—rectangular & hard-edged, with a few scattered offerings, including a small photo of a young woman, her eyes closed. Every year, on Brigid’s Feast Day, the 1st of February, the fire is lit again. But as Todd & I wander the grounds of the cathedral, the call seems fainter. There is a Round Tower, tall & phallic, which the tiny female caretaker, her purse strapped to her chest in a tight diagonal as if afraid we’ll try to steal it, tells us we’re too late to climb, but I don’t mind. I feel no magic emanating from this stone tower, & none from the Fire Pit.

The call nearly disappeared outside the cathedral, but it resumes as we follow the obscure directions to Brigid’s Well, get lost, retrace our steps, & try again. We pass signs for the National Stud (a horse farm), the Black Abbey, & an outlet mall. And then a small sign to Brigid’s Well, with an arrow pointing vaguely in the distance. “How can there be signs to Brigid’s Well & an outlet mall on the same post?” I muse aloud. Is that a sign that there is no distinction between the sacred & the profane, that it is all one?

Evening is falling when we finally find the well, a green sanctuary on the side of the road. A fence separates this enclosed area from a field. I should have been prepared for the juxtaposition of the mystical & the kitsch—a small shrine at the entrance contains tiny dolls & statuettes, burnt candles, & a large snow globe of Mary & disciple (without the snow). We walk deeper into the sanctuary to the well, guarded by a life-size stone figure of Brigid holding up her hand in welcome. Under one arm, she grips a cane & flowers. The well is a small stream, murky & lily-dotted. A series of stones marks a path to another stone circle, a place to sit & meditate. At the end of the clearing is a tree, its branches strung with colorful Tibetan flags, ribbons, keychains, & pieces of yarn. It reminds me of a tree in Safed, a town of mystics in Israel, where I visited the shrine of a saintly Kabbalist rabbi. His tree was weighed down with hundreds of ribbons & scarves, all bearing prayers & yearnings.

A sudden green breeze carries me back to that windy day on top of a hill in Safed (pronounced Tzfat—Hebrew, another coded language with letters that function as doorways into the unknown). I’d been given crazy-chaotic directions to his sacred tree by a mystic. It took 90 minutes of winding through wooded dead-ends & wildly careening roads to find the tree. Later, I learned it was an easy 15-minute ride from the center of town, but when I asked my friend why I’d been given such a maze to follow, she said, “It shouldn’t be too easy to find the sacred. That ride through the dark & the unknown was your preparation.”

Todd & I are silent, but it is clear we both hear the call. Something magical is happening. We have entered a sacred space, & we try to remember this moment—each in our own way. He takes pictures, & I sit at the edge of the well & write. We linger & lose track of time.

After a while a woman climbs through the slats of the fence & enters the sanctuary with a small white muzzled Rottweiler. We talk dogs with her for a while, as she sits on a bench, smokes, & lets Daisy, the Rottweiler, wander. Dark-haired, pale, long-limbed, she won’t let Todd take her picture. She seems to fit perfectly in this space, & when she finishes her cigarette, goes to check on the shrine. When she returns to us, it’s as if she’s made up her mind to confide in us. “You know this isn’t the original well?”

Todd & I exchange glances. What?

She explains that there was no parking at the original well, & so her father donated part of his land—their property is just beyond the fence—to build a new well in 1955. The old well is minutes away.

We find it quickly, in the shadows of the ominously named Black Abbey, a grim abandoned stone tower with tall grasses blowing across Celtic cross-topped tombstones. I can’t stop laughing. I’m a little giddy—we did feel the sense of the sacred, I know in my bones that we did, but does the fact that we were in the wrong place invalidate that? What defines a sacred space anyway? Is it sacred before we arrive? Does our presence make it sacred?

The original well is smaller & simpler, lonely, guarded by a weeping willow and a tree branch strung with about a dozen ribbons & wishes. We’d never have found it without the woman. After the sacred experience at the other well, I still feel magic dripping from me, & sheer joy: we are here, in Kildare, at the original well, & all of this has come about because months ago I scribbled a few words about Goddess sites, including this: “Brigid’s Well, Kildare.” I didn’t know if I’d ever make it here, didn’t know where or when or how, but the intention was there.

There is power here—in the other well, & in this one, too—& I wonder if it was always there, or if we, the seekers, are the ones who bring it.

Water softly gurgles, & leaves scattered over the green green grass remind me it’s autumn. I climb over rocks to the center of the well & sit, cloaked in golden light. For a moment, I feel like a Goddess myself.

Before we leave, I send a prayer—words, my magic—into the water & green-blue air. I hope she accepts my offering.

I hear the call in the deep heart’s core. --Yeats

I heard it across the seas in the rustling forest near my home in Pennsylvania, & I heard it in the sound of the waves, & I heard it the instant we docked in the port of gritty & raw Dublin, one of my favorite cities in the world. I’ve only been here once before, for a wonderful Thanksgiving week with my son Avi, but it was enough to make me want to return. What I remember: the words of James Joyce across the window of the Guinness Storehouse as you survey Dublin over a foaming pint, the musty welcoming smell of old books in the Long Library at Trinity College, the forty shades of green in the parks, the rich, dark coffee, & the sweet sharpness of the language. Whether the Irish speak Gaelic or English, whether they’re joking or telling tales, there’s music to the words, a cadence & rhythm that invokes & evokes the soul’s mysteries the way poetry does. It’s a code to decipher & puzzle over. Letters take on new identities, others are present but silent, while others are heard but not seen. Niamh = Neve. Sidhe = She. The words curve like fingers & beckon into the woods, whisper the divine call of the Sidhe, those mischievous faeries: Away, come away (said Yeats, who heard them, too).

And then they leave us in the woods, our hearts tied in a Celtic knot, our eyes staring wistfully.

I hear the call as I leave the dock with my friend & Semester at Sea colleague, photographer Todd Forsgren. We head in search of the sacred feminine, & the first thing we see is a small statue of Mary guarding the sailors, & those who have sinned.

I hear it stronger inside the crypt of Newgrange, the Neolithic passage tomb, with its prophetically accurate Roof Box, a carved opening that lets in the sun during the Winter Solstice—perhaps the world’s first solarium. I lift my head to the vaulted carbelled roof, layer upon layer of scalloped, fitted rock that reportedly hasn’t leaked a drop of water (in rainy Ireland) in 5,000 years, & gaze at the mystical symbols—tri-spirals, diamonds & zigzags—carved into the recesses. The guard—an irreverent man with a metallic-gray Elvis pompadour & a side-creeping smile—turns off the light & says, “Imagine the Sun God penetrating the Earth Goddess to make the earth fertile.” A dazzling ray of light filters through the Roof Box & lights the crypt. I know I’m not the only one who shivers. It’s very sexual, very Demeter, & very powerful. I’m especially moved when I learn that the 92 massive rocks that circle the round tomb of Newgrange are carved with the same mysterious symbols as Howth (the neighboring passage tomb), but unlike Howth, where the rock carvings face outwards as if to protect those inside from invaders—at Newgrange, the carved symbols face inward, like magic amulets pressed to your heart.

I hear it deeper inside my heart as we enter Kildare, a medieval town dominated by St. Brigid’s Cathedral on one side of the town square. Cill = Church. Dara = Oak. Apparently Brigid, who was a real person before she became a legend—saint, goddess & witch—was beautiful & headstrong, & wandered the country in search of a place to set up her church. She found it here, in an oak ridge & set out her magically expanding cloak to mark the dimensions of the land. She built the first monastery in Ireland, & curiously one where monks & nuns cohabited (separately, but under the same roof). She was the Abbess, but so powerful she was known as a Bishop.

Inside the cathedral, which is as musty as the Long Library, we hear a persistent humming. Is that the call? Todd & I walk from one altar to another, surrounded by dark, damp stone, searching for the source of the humming. Is someone confessing in a hidden alcove? Is the cathedral haunted? The mystery is cleared up when we walk outside & wander the grounds. A weed whacker! An absurd prosaic detail that reminds me of exiting the sacred mysterious crypt of Newgrange to see a pasture of dozing cows a few feet away. The sacred & the profane rub shoulders in Ireland.

Behind the cathedral is a Fire Pit where Brigid started a fire that burned without ashes for centuries. It was tended by nineteen nuns. Every night the nuns chanted, “Brigid, take care of your own fire for this night belongs to you,” & in the morning, the fire would still burn bright. Brigid died in the year 525, but the fire burned on until a priest magically put out the flames. And that was the end of the fire.

I visit the Fire Pit—rectangular & hard-edged, with a few scattered offerings, including a small photo of a young woman, her eyes closed. Every year, on Brigid’s Feast Day, the 1st of February, the fire is lit again. But as Todd & I wander the grounds of the cathedral, the call seems fainter. There is a Round Tower, tall & phallic, which the tiny female caretaker, her purse strapped to her chest in a tight diagonal as if afraid we’ll try to steal it, tells us we’re too late to climb, but I don’t mind. I feel no magic emanating from this stone tower, & none from the Fire Pit.

The call nearly disappeared outside the cathedral, but it resumes as we follow the obscure directions to Brigid’s Well, get lost, retrace our steps, & try again. We pass signs for the National Stud (a horse farm), the Black Abbey, & an outlet mall. And then a small sign to Brigid’s Well, with an arrow pointing vaguely in the distance. “How can there be signs to Brigid’s Well & an outlet mall on the same post?” I muse aloud. Is that a sign that there is no distinction between the sacred & the profane, that it is all one?

Evening is falling when we finally find the well, a green sanctuary on the side of the road. A fence separates this enclosed area from a field. I should have been prepared for the juxtaposition of the mystical & the kitsch—a small shrine at the entrance contains tiny dolls & statuettes, burnt candles, & a large snow globe of Mary & disciple (without the snow). We walk deeper into the sanctuary to the well, guarded by a life-size stone figure of Brigid holding up her hand in welcome. Under one arm, she grips a cane & flowers. The well is a small stream, murky & lily-dotted. A series of stones marks a path to another stone circle, a place to sit & meditate. At the end of the clearing is a tree, its branches strung with colorful Tibetan flags, ribbons, keychains, & pieces of yarn. It reminds me of a tree in Safed, a town of mystics in Israel, where I visited the shrine of a saintly Kabbalist rabbi. His tree was weighed down with hundreds of ribbons & scarves, all bearing prayers & yearnings.

A sudden green breeze carries me back to that windy day on top of a hill in Safed (pronounced Tzfat—Hebrew, another coded language with letters that function as doorways into the unknown). I’d been given crazy-chaotic directions to his sacred tree by a mystic. It took 90 minutes of winding through wooded dead-ends & wildly careening roads to find the tree. Later, I learned it was an easy 15-minute ride from the center of town, but when I asked my friend why I’d been given such a maze to follow, she said, “It shouldn’t be too easy to find the sacred. That ride through the dark & the unknown was your preparation.”

Todd & I are silent, but it is clear we both hear the call. Something magical is happening. We have entered a sacred space, & we try to remember this moment—each in our own way. He takes pictures, & I sit at the edge of the well & write. We linger & lose track of time.

After a while a woman climbs through the slats of the fence & enters the sanctuary with a small white muzzled Rottweiler. We talk dogs with her for a while, as she sits on a bench, smokes, & lets Daisy, the Rottweiler, wander. Dark-haired, pale, long-limbed, she won’t let Todd take her picture. She seems to fit perfectly in this space, & when she finishes her cigarette, goes to check on the shrine. When she returns to us, it’s as if she’s made up her mind to confide in us. “You know this isn’t the original well?”

Todd & I exchange glances. What?

She explains that there was no parking at the original well, & so her father donated part of his land—their property is just beyond the fence—to build a new well in 1955. The old well is minutes away.

We find it quickly, in the shadows of the ominously named Black Abbey, a grim abandoned stone tower with tall grasses blowing across Celtic cross-topped tombstones. I can’t stop laughing. I’m a little giddy—we did feel the sense of the sacred, I know in my bones that we did, but does the fact that we were in the wrong place invalidate that? What defines a sacred space anyway? Is it sacred before we arrive? Does our presence make it sacred?

The original well is smaller & simpler, lonely, guarded by a weeping willow and a tree branch strung with about a dozen ribbons & wishes. We’d never have found it without the woman. After the sacred experience at the other well, I still feel magic dripping from me, & sheer joy: we are here, in Kildare, at the original well, & all of this has come about because months ago I scribbled a few words about Goddess sites, including this: “Brigid’s Well, Kildare.” I didn’t know if I’d ever make it here, didn’t know where or when or how, but the intention was there.

There is power here—in the other well, & in this one, too—& I wonder if it was always there, or if we, the seekers, are the ones who bring it.

Water softly gurgles, & leaves scattered over the green green grass remind me it’s autumn. I climb over rocks to the center of the well & sit, cloaked in golden light. For a moment, I feel like a Goddess myself.

Before we leave, I send a prayer—words, my magic—into the water & green-blue air. I hope she accepts my offering.

Published on October 03, 2014 08:14

September 26, 2014

PARIS: BREATHING ART

It’s everywhere & it hits every sense, sometimes all at once.

You can’t just walk by a patisserie with the aroma of fresh-baked petits pains au chocolat. You breathe in the fragrance, you see the displays of breads & pastries in the window, & if you’re like me, you buy a petit pain so you can hold it, warm & flaky, & bite into perfection that melts on the tongue. Pass it down with strong coffee (yes, my two loves: coffee & chocolate).

A moment of indecision: keep walking or sit at a small table?

I set down my little package & coffee gratefully, & add people-watching to the pleasures.

Living, breathing, walking art. French people know how to dress, how to make the most of what they’ve got. They invented the wonderful term: beaute laide, or ugly beauty. Someone who is not classically, symmetrically beautiful, but who has a je ne sais quoi that creates the illusion of beauty, or something more. I see it in the movie stars they love & in the people who pass me. My unofficial verdict? The art of dressing well & looking French is a mix of two things: the appearance of utter confidence & utter effortlessness. Note I said “appearance.” Your hair falls in softly tousled waves, your top shirt buttons are open because you can’t be bothered, your make-up subtle because who has time … but your skirt and jacket fit like gloves, & your shoes & accessories are gorgeous. Unforced elegance.

A city of museums, cathedrals, fashion, ethnic neighborhoods—a city that values the art of being human. Around every corner you stumble into art. And by art, I mean not only the magnificence of the sculptures & paintings at the museums that fill this city, but the heightening of daily life, the awareness that life itself is an art, & that every moment deserves focus & awareness.

The small church of St. Severin. After the massive, gloomy hunchback-haunted grandeur of Notre-Dame, St. Severin seems cozy—if you can say that about a dark church. What I like are the columns shaped like palm trees & the abstract vivid stained glass windows, the straw-woven chairs that evoke the Mediterranean.

The waitresses dressed in beautifully fitted black & white at the wonderful, touristy Relais de l’Entrecote. Smiling & precise, as if moving through the steps of a dance only they hear, they set the red, green, blue & yellow tables. Outside, on the sidewalk, the line forms to wait for 7:00, when they can enter to eat steak & fries.

On a weekday night the cafes are crowded with people drinking good wine & eating under bright moon, talking & laughing. Savoir vivre—the art of living life. An art I wish we’d remember more often in the States.

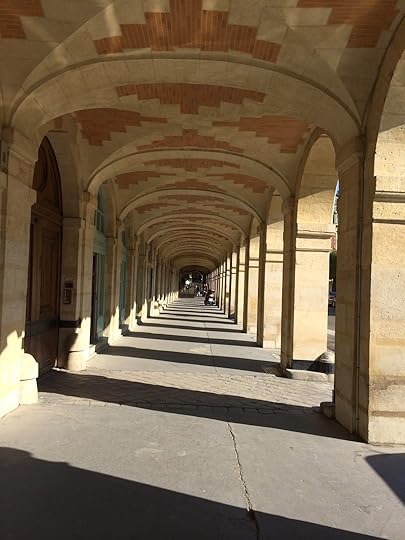

Enter the Hotel Sully near the Bastille, walk through to the garden, & you will emerge in the Place de Vosges, Paris’s oldest square, lined by a mysteriously shadowed corridor. Keep walking, & you find yourself in the Marais, the old Jewish quarter. Now a network of trendy stores, galleries & cafes, but there is the wonderful surprise of the rue des Rosiers with its Hebrew signs, store windows with sacred books, & tiny restaurants offering kosher falafel & shwarma, just like in Jerusalem. Stand in line at l’As de Falafel with a dozen others, buy a falafel in pita stuffed to the brim, take it to a small shady park around the corner, & sit on a bench for more people-watching. Paris—like every European city—is multicultural, & I hear French spoke in many different accents.

I wander through the Musee d’Orsay—one of the most breathtaking museums in the world—and wander back out, dazed by the lights in Van Gogh’s Starry Night & Carpeaux’ smiling marble dancers, to the banks of the Seine, where vendors sell old books, magazines, posters & postcards, & lovers kiss on the steps leading to the river. I have the urge to dance up & down the steps like Gene Kelly in An American in Paris.

Instead I sit on the top step, chin in hand, & stare at the sun setting over the Seine.

But I can’t stop my feet from tapping out the melody.

Published on September 26, 2014 02:20

September 21, 2014

ANTWERP: Solid Magic

Rubens' Bed

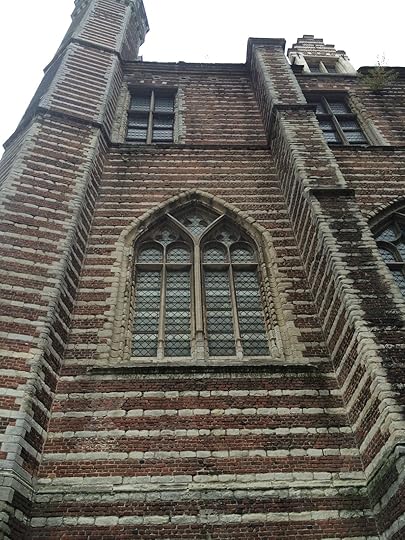

Rubens' BedThis town is exactly the right size—not too large, not too small. The Butchers’ Hall (built in 1501) is one of the most impressive buildings, its small red & beige bricks echoing the colors of bacon. At one side of City Hall, other Guilds are lined up in narrow buildings. The Artists rent a floor in another Guild. Clearly, they are not as important as the Butchers.

The legend that defines the city is that of Brabo, the mythical hero who decided to fight the giant who lived in the River Scheldt & who’d been terrorizing the inhabitants. After Brabo tore off the giant’s head, he ripped off the giant’s hand & tossed it into the river. The hand is the symbol of Antwerp. Ant = hand. Werp = to throw. You find the hand all through town. Its most delicious form is in small chocolate. Inside the chocolate hand is a mixture of marzipan & liquor of Anvers, which is supposed to have six healing (& aphrodisiac) qualities. I can’t vouch for that, but I can say that the chocolate hand was exquisite, like much of the chocolate here, including the fantastical creations of the chocolate chef at the Imperial Café who oversees Napoleon’s former kitchen.

Waffles, powdered sugar, & chocolate are Pied Pipers that lead us down the web of cobbled streets. When the stomach is full & satisfied—frites dipped in mayonnaise; mussels; waffles smothered with fruits, chocolates & whipped cream; chocolates, of course; and hundreds of varieties of beer—then, the spirit can soar.

A few of my favorite places:

Plantinus Maretus-- a family dynasty of printers whose house is now a museum that includes the oldest printing presses in the world, dating from 1600. The motto of Golden Compasses, their printing shop, “Work and Persevere,” could be the motto of the entire town.

The Antwerp Train Station (seen above, at a diagonal)—grand & luminous, reputed to be the most beautiful in the world. The Gothic arches of the cathedral in the heart of the old town. Both rise toward the sky, but both are grounded in solid earth.

The Mas Museum—an eccentric, eclectic collection of themed art exhibits. From the roof you can see all of Antwerp, from the old town to the port.

St. Paul’s Church, formerly a Dominican monastery (from 1256-1796)—a refuge of complete serenity.

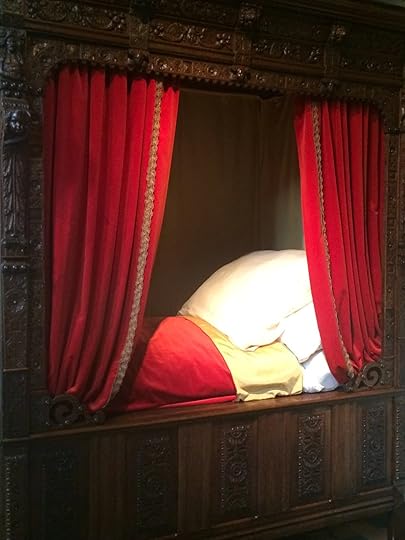

Rubens' house. Rubens himself is the patron saint of Antwerp, the brilliant, lusty human embodiment of Brabo. Here, we see the artist as wealthy investor & prominent citizen of his town. No freezing artist’s garret for our Rubens. His house is enormous—he merged two houses & connected them with a garden—wonderfully organized, yet bursting with fig & orange trees—that echoes the garden at Plantinus Maretus (the printer whose son was a friend of Rubens). The wood in Rubens’ house is dark, the furniture as solid & earthy as the artist. At 53, he married his second wife, the 16 year-old Helena, a widow herself who’d posed nude for him. After Rubens died ten years later, leaving her a wealthy widow with five children, Helena married again—a man ten years younger. I want to know more about her!

Walking in Antwerp, past the old town & crowded Meir Street with its Esprit, H&M, Starbucks, & the other symbols of Western consumerism, I find a gold & red Chinese archway leading into Chinatown, & smaller markets & streets—women wearing hijabs push children in carriages, men smoke outside Turkish cafes, an African man in a lime-green suit sings in lilting English, “Jesus touched me! Something happened to me today!”

A sudden memory: Charlotte Bronte’s brilliant, tormented novel, Villette, which takes place in Brussels, where she spent a love-agonized year. Who can forget Lucy Snowe’s unrequited passion for her teacher, the mercurial, moody M. Heger, who sees through her plain, subdued exterior to the wild heart bursting to be set free? I remember my professor's dismissive comment: "All this emotion in placid Belgium?"

But all you have to do is wander the cobbled streets & surprising gardens, bite into a chocolate hand, tilt your head back & stare at the luminous roof of the train station or the spire of the cathedral or even the roof of the Butchers' Hall, or stand before Rubens’ sensual & vibrant paintings of the flesh to know there is nothing placid about Belgium. In Rubens' house, the three-headed marble statue of the goddess Hecate watches over the vast underground workshop where he created masterpieces & the tiny red velvet covered bed where he sat up all night & dreamed magic.

The Butchers' Hall

The Butchers' Hall

Published on September 21, 2014 02:47

September 15, 2014

Being a Travel Writer

We are fortunate to have a guest post by my friend & colleague, the talented, multi-published author who has written about everything from ghost-hunting & serial killers to Anne Rice's vampires. Take it away, Katherine!

By Katherine Ramsland

I never aspired to be a travel writer, but I love to travel and I write nonfiction, so it was inevitable that the two would merge. For the past year, I’ve published monthly “Crime-trotting” columns for Darlene Perrone’s Destinations Travel Magazineonline. This opportunity developed from sheer serendipity.

I met Darlene at the Bedford Springs Resort Hotel in Pennsylvania. Not long afterward, a mutual friend told me that Darlene was looking for writers. Since I was on my way to New Mexico for a Georgia O’Keeffe pilgrimage at Ghost Ranch, I pitched it to Darlene.

I figured that not many people had been to Ghost Ranch, just north of Abiquiu, where O’Keeffe once had a home. This seemed like the perfect place to get photos and anecdotes. But while I was there, I discovered a little-known fact about the ranch. The pair of brothers who’d first settled it had murdered a number of cattlemen to steal their herds. Eventually, one brother killed the other and got hanged for his crimes.

Thus was born my column. Ghost Ranch might have inspired Georgia O’Keeffe in the gentle art of landscape painting, but it was founded by serial killers. Then, in Santa Fe, I located the “first house” in the country. It turns out that a murder had happened here as well. When I wrote about it, we learned that these dark elements appealed to readers.

So, each month I look for places where fascinating crimes occurred that also offer touristy things to do. For example, a large house in Villisca, Iowa, was the scene of a sensational mass murder a century ago, and you can take a tour. Then, there’s the Lizzie Borden house in Fall River, MA, which has been turned into a “crime-scene” bed and breakfast. I also wrote about the Jesse James Farm, where the outlaw is buried and a museum stands, and surprised many people with the story of a massacre at Frank Lloyd Wright’s tourable Wisconsin estate, Taliesin.

One of my favorite stories occurred in Deadwood, South Dakota. This is where Wild Bill Hickock was assassinated under peculiar circumstances. The town retains much of the flavor from those days. It’s had a resurgence of interest since the HBO Show, Deadwood, was developed around some actual people and events.

The column is fun, but there’s a difficult part: deciding when a place is appropriate for “murder tourism” and when it’s not. I’m aware that there’s a Jeffrey Dahmer tour in Wisconsin, for example, but we thought that featuring it seemed tasteless. In fact, I know quite a few places with serial killer associations. However, we prefer incidents where there’s some psychological distance between the event and the idea of a visit. This certainly limits what I can write about, but it’s also a challenge.

So, from my experience, here are the top five things I can suggest for travel writing:

1) Learn some basic photography concepts and skills. I knew very little about taking pictures when I first started, but since then, I now know a lot about perspective, DSL-R cameras, enhancement software, and best times of day for shooting.

2) Be vigilant for opportunities. I happened to be presenting at a conference in Tucson, and the driver who picked me up at the airport mentioned a hotel downtown where the John Dillinger Gang had been arrested in surprise ambush. I found a way to get downtown to get the story. It became one of my columns, and the hotel was quite photogenic.

3) Think about travel practicalities. I can find stories to write about, but if people can’t get there, or it’s set in an inaccessible place, that’s not appropriate for crime-trotting. For example, the house where the Clutter family was slaughtered in 1959 in Kansas is a private home. Yet, it was the subject of Truman Capote’s best-selling In Cold Blood, so it was the perfect tale for my column. Instead of focusing on the house, I had photos from several buildings in town that Capote described in the book.

4) Focus on variety. I go from Southwestern deserts to the Midwest plains to New England to an international location (my self-designed Jack the Ripper tour). Right after I wrote about the upper crust Taliesin rampage, I traveled to Gibsonton, Florida, where carnival people once wintered, to describe the murder of a man known as Lobster Boy.

5) Be mindful of the psychology of travel. There are hardcore murder tourists who want the gruesome details, but this magazine does not cater to them. It’s a column that provides the typical traveler with something curious and unique. We don’t want to upset or annoy people, we want to provide interesting glimpses into history and locale.

These are the lessons from my year as a travel writer. Next up is a column on the century-old crime museums of Europe. Crime-trotting can be found at: http://destinationstravelmagazine.com/

Katherine Ramsland has published over 1,000 articles and 54 books. She teaches forensic psychology and criminal justice at DeSales University in Pennsylvania, writes a blog for Psychology Today and a travel feature for Destinations Travel Magazine.

www.Katherineramsland.com

Published on September 15, 2014 21:57

September 11, 2014

BERLIN: Stumbling Stones & Street Art

The Holocaust Memorial

You stumble over the plaques in the concrete. Like small stones, they slow you down, force you to look twice. And that’s the point. You stop & crouch to read what is inscribed on the brass plaque:

HIER WOHNTE MAX SOMMERFELDJ8.1885DEPORTIERT 27.11.1941RIGAERMORDET 30.11.1941

There are five Stumbling Stones, or Stolpersteine, outside my friend, writer Kenny Fries’s apartment. As I stare down at them, Kenny & his husband Mike wait patiently for me to grasp the import.

They’ve taken me from one surprise to another during our evening in their new hometown, Berlin, which they already know & love. It’s a warm, glorious September night as we walk past the Neue Synagogue, which looks enchanted & golden, & then down Karl Marx Allee—formerly Stalin Allee—a vast street lined by faceless concrete apartment blocks intended for members of the Communist Party, & for victory parades & marches. It now looks faintly forlorn. The entire street is a monument to a triumph that never happened. I do a double take at the Karl Marx Bookstore & peer inside the large windows at an arched interior. Empty.

“Today it’s a printing press,” Kenny informs me, “but they kept the sign & the original design.”

In St. Petersburg & in Gdansk, I saw wounded buildings, slashed with horrors of war, & bandaged with colorful new facades, but somehow the bloody past always leaks out (see my previous post on Gdansk). In Berlin, the Jewish Museum & the Holocaust Memorial provide interesting switches. The Jewish Museum, with the broken Star of David on its punctured facade, works with the senses to recreate the terror of Jews in Germany during World War II. The ground shifts beneath your feet, white noise accompanies you, & walls close in, leaving you dizzy & claustrophobic. The Holocaust Memorial, with its maze of coffin-like gray pillars lining narrow corridors & abrupt Escheresque twists & turns, makes you doubt the faint light at the end of the tunnel … as if you’ll wander down these dark corridors like Kafka’s Joseph K for the rest of time. At every corner, you stumble over memories & ghosts, & “Jew” whispers in your ear.

“When Americans try to speak German, they always sound so harsh & guttural,” says Kim, a young British-educated German guide. “They exaggerate every sound. That’s not how we talk.”

For Berliners, the defining moment of history is not World War II, but the Berlin Wall being torn down 25 years ago.

Kenny, Mike & I stand in front of the Tacheles—which sounds like a Hebrew prayer, but is the last standing Squatters’ House. When the Wall came down, East Berliners immediately evacuated their homes & escaped to West Berlin. Struggling young West Berliners sneaked into East Berlin & occupied the abandoned houses. Some remained for years, but most were eventually kicked out. At night the Tacheles looks raw & gaping, black orifices plugged by posters, slogans, spray paint—the new language of art.

The following day, Ben, a street artist who calls himself El Kapitano del Karacho (Brazilian friends informed him it means: Captain of the Penis), takes us to Friedrichain, a shady neighborhood known for drugs & danger, & its graffiti. “Don’t buy your drugs from pushers here,” he advises. “And don’t get drunk in bars here.”

He leads us to an old train station—a dizzying whirl of spray paint, rollers, posters, & wall art covering decay, poverty & disintegration. After a few hours at the Black Market Collective, a large warehouse where I created my own version of street art—a stenciled portrait of John Lennon—digging my Exacto-knife, spraying pain, shaking it dry—I understand the excitement. It’s like being a kid let loose in an art studio, only the entire city is your canvas.

“We’re criminals,” says Ben gleefully. “The fine for graffiti is 463.60 Euros, & with a court case & lawsuits, it can go to 2,000 Euros. But there’s no thrill like painting a wall & running to hide a second before the cops drive by.” The street artists travel in packs: the artist, checkers on the next corner with walkie talkies—no phones because they may be tapped. Black hoodies & face masks, & they carry knives & baseball bats to look intimidating. Sometimes a film crew because they want to be documented. Ben points out the work of known artists like Sobre, El Bocho, & Jimmy C known for social criticism & conspiracy theories.

“Ah!” I jump in here. “so you want to be known, but not caught. Is that what it’s about?”

“Yes…. Street art began with writing your name on a wall, but look at a group like 1UP.”

In the train station an art exhibit is devoted to an internationally known street art group that moves from city to city, films their work in documentaries, puts together (expensive) volumes of their art, & signs themselves: 1UP. No personal signatures, just 1UP, which comes from Super Mario Brothers, & can stand for 1 United Power. Street artists know their work will be plastered over, repainted by the city & other artists. That doesn’t concern them. What’s important is the thrill, the moment. Street bombing, murdering a wall, the explosion of art—a happening. And then, moving on. The next wall, the next challenge, the next city.

In the train station an art exhibit is devoted to an internationally known street art group that moves from city to city, films their work in documentaries, puts together (expensive) volumes of their art, & signs themselves: 1UP. No personal signatures, just 1UP, which comes from Super Mario Brothers, & can stand for 1 United Power. Street artists know their work will be plastered over, repainted by the city & other artists. That doesn’t concern them. What’s important is the thrill, the moment. Street bombing, murdering a wall, the explosion of art—a happening. And then, moving on. The next wall, the next challenge, the next city.After Ben leaves, I walk along the remaining parts of the Wall, known as the East Side Gallery, possibly the largest outdoor art gallery in the world. The Berlin Wall—painted, graffiti’d, layer upon layer, smeared & sprayed to the last inch. Street art at its ultimate power: the voice of the people speaking out, protesting, creating beauty (however you define it) in the face of repression.

the famous kiss on the Berlin WallBut.

I stumble as if the Stolpersteine are under my feet. Later, I learn that they are an art project for Europe by Gunter Demnig, commemorative brass plaques set in the pavement in front of the deported person’s last address of choice. Demnig was inspired by the Talmud: “A person is only forgotten when his or her name is forgotten.” Each stone begins: HERE LIVED …

“One ‘stone’,” he writes. “One name. One person.”

Standing at the Wall, I close my eyes & see artists madly painting over bloodstains, punctures, gaping wounds… & running in the night. And others carving a broken Star of David, tilting the ground beneath our feet, hammering in brass plaques, & forcing us to stumble. To remember.

Published on September 11, 2014 23:43