Chandrahas Choudhury's Blog, page 4

January 10, 2017

On Donald Lopez's The Lotus Sutra: A Biography

This piece appeared recently in the Wall Street Journal.

Every morning at thousands of Buddhist shrines in Japan—and at the Nichiren Temple in Queens, N.Y., the Rissho Kosei-Kai Center of Los Angeles, and the Daiseion-Ji temple in the small town of Wipperfürth, Germany—there rises the chant “Nam myoho renge kyo.” These five syllables don’t sound so lyrical in translation—“Glory to the wonderful Dharma of the Lotus Flower Sutra”—but for those who utter them they proclaim the enduring mystery, wisdom and salvific power of one of the most important and ancient books of Buddhist teachings, the Lotus Sutra.

Every morning at thousands of Buddhist shrines in Japan—and at the Nichiren Temple in Queens, N.Y., the Rissho Kosei-Kai Center of Los Angeles, and the Daiseion-Ji temple in the small town of Wipperfürth, Germany—there rises the chant “Nam myoho renge kyo.” These five syllables don’t sound so lyrical in translation—“Glory to the wonderful Dharma of the Lotus Flower Sutra”—but for those who utter them they proclaim the enduring mystery, wisdom and salvific power of one of the most important and ancient books of Buddhist teachings, the Lotus Sutra.

The lotus, which roots in mud, rises up through water and raises its beautiful petals towards the sky, is the most ubiquitous of Buddhist motifs, an image of the ascent from the morass of worldly desires and suffering to beauty, peace and virtue. Sutra comes from the Sanskrit word “sutta” or “thread,” meaning a set of thoughts or aphorisms on a given subject (as in the Kama Sutra, a treatise on love and courtship). Since there is no written record of Buddhist doctrine from the time of the Buddha, the canon of Buddhist literature brims with hundreds of such sutras which purport to reveal his true teaching.

The Lotus Sutra has a special place in the Buddhist canon. A lively if often confounding grab bag of parables and proclamations told in both prose and verse, it is rich in narrative pleasure and contains more braggadocio than a Donald Trump speech. (“The Buddha is the king,” we read at one point, “this sutra is his wife.”) Indeed, many scholars trace its self-promotional tone back to the era of its composition, when it had to establish itself within a crowded market of religious texts and sects in India. The nature of the Lotus Sutra’s influence is taken up by the scholar of Buddhism Donald S. Lopez Jr. in the latest in Princeton University Press’s excellent series on the “lives of great religious books.”

As with so many religious works from antiquity, the Sutra has a history shrouded in uncertainty. Even its authorship is a mystery. By the time it was composed in Sanskrit early in the first millennium, the Buddha had been dead for 500 years. His striking message, at once austere and compassionate, offered a vision of liberation resolutely free of mythological content. The Buddha’s eerily convincing diagnosis of the nature of human suffering and the way to transcend it had achieved a wide currency in India and had extended to China and Sri Lanka. But Buddhism had begun to break up into sects over divergent interpretations of the teaching.

The major schism was between the Hinayana and the Mahayana. The Hinayana school stressed the importance of monastic life as the only real path to liberation. Mahayana Buddhism, on the other hand, was much more worldly even in its quest for transcendence. Its hero was not the “arhat,” or the being who has attained nirvana, but the “bodhisattva,” the enlightened person who perceives the truth but stays behind in the world to help others across to the far shore of peace.

The Lotus Sutra is a classic—and cacophonous—Mahayana text. The book unfolds as a series of dialogues between the Buddha and his followers, many of them men of great spiritual prowess themselves. The text slowly and artfully builds to a revelation: that of the “saddharma,” or true dharma. The Buddha reveals to his interlocutors that the “threefold path” that he teaches in other texts—a somewhat arcane theory of different streams of learning and discipleship that open out paths to liberation—is actually something of a deception.

In truth, there is only a single Way. But “this Dharma is indescribable / Words must fall silent.” (A very lucid account of the possible nature of this vision, which the Buddha says cannot be formulated in language, can be found in Heinrich Zimmer’s 1952 book “Philosophies of India.) The Buddha is so far gone, he explains, that had he taught such a difficult doctrine, he would have made himself clear to precisely nobody. Instead, he used the path of “skillful means” to set people off on the path to transcendence, preaching to each person according to his estimate of their capacity for enlightenment.

With this master stroke, the Lotus Sutra makes the goal of liberation at once more mysterious and more practicable (and, conveniently, knocks out other sutras competing for the attention of the faithful). The ultimate goal, so elusive, seems almost unattainable, but this makes every teacher a student and every student part of a great, throbbing chain of learning. Indeed, following the Buddha, any teacher must think seriously not just about knowledge, but the right way to transmit it. In this way, the Lotus Sutra makes itself indispensable not just as a teaching, but as a tool of pedagogy. As Mr. Lopez writes: “Perhaps the central teaching of the Lotus Sutra is to teach the Lotus Sutra.”

The allure of Buddhism eventually faded in the land of its birth, where Hinduism was too vivid and well-established to give way to this more introspective ideology. But the Lotus Sutra and other key texts gradually took root in others lands and languages. To the raft of entertaining characters found in the text itself—peasants and princes, initiates and religious masters, the Buddha as both truth-teller and deceiver—Mr. Lopez’s book adds a cast of historical figures across two millennia united only by their passion for the book, including the 13th-century Japanese monk Nichiren, whose fire-and-brimstone message declaring all other Buddhist texts but the Lotus Sutra to be heretical earned him a long incarceration on a lonely island, and Gustave Flaubert.

The author focuses on two especially interesting figures, both of them translators. The first, the Buddhist monk Kumarajiva, lived in eastern India in the 4th century, and had the misfortune of being taken hostage by an invading Chinese general. Over long years as a prisoner, he picked up enough Chinese to translate the Lotus Sutra for the benefit of the Chinese emperor, already a devout Buddhist. Thus the Sutra took root in China, and spread slowly through the Far East.

Just as fascinating is the story of how the book arrived in the West. The Sutra was among a large cache of Buddhist manuscripts sent early in the 19th century to the French Sanskritist Eugène Burnouf by Brian Hodgson, an enterprising young officer of the British East India Company. Burnouf immediately set to translating it, noting among other things the book’s “discursive and very Socratic method of exposition.” His French version, published posthumously in 1852, made its way across the Atlantic, where it was picked up and circulated in translation by Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Transcendentalists, who regularly published scriptures from Asia in their magazine, the Dial.

Mr. Lopez’s book shows us that translators are the unsung heroes of religious, as much as literary, history. Here he has serviced the text with yet another sort of translation—this one to a general audience.

The Lotus Sutra is a rejection, observes Mr. Lopez, of the kind of nirvana “that is a solitary and passive state of eternal peace.” Rather, we are all travelers on a long road, even the enlightened ones among us; we cannot see through to the end right from the start and must begin with small acts of compassion and caring. The inspiring message of the Lotus Sutra is that buddhahood is immanent in all of us.

Every morning at thousands of Buddhist shrines in Japan—and at the Nichiren Temple in Queens, N.Y., the Rissho Kosei-Kai Center of Los Angeles, and the Daiseion-Ji temple in the small town of Wipperfürth, Germany—there rises the chant “Nam myoho renge kyo.” These five syllables don’t sound so lyrical in translation—“Glory to the wonderful Dharma of the Lotus Flower Sutra”—but for those who utter them they proclaim the enduring mystery, wisdom and salvific power of one of the most important and ancient books of Buddhist teachings, the Lotus Sutra.

Every morning at thousands of Buddhist shrines in Japan—and at the Nichiren Temple in Queens, N.Y., the Rissho Kosei-Kai Center of Los Angeles, and the Daiseion-Ji temple in the small town of Wipperfürth, Germany—there rises the chant “Nam myoho renge kyo.” These five syllables don’t sound so lyrical in translation—“Glory to the wonderful Dharma of the Lotus Flower Sutra”—but for those who utter them they proclaim the enduring mystery, wisdom and salvific power of one of the most important and ancient books of Buddhist teachings, the Lotus Sutra.The lotus, which roots in mud, rises up through water and raises its beautiful petals towards the sky, is the most ubiquitous of Buddhist motifs, an image of the ascent from the morass of worldly desires and suffering to beauty, peace and virtue. Sutra comes from the Sanskrit word “sutta” or “thread,” meaning a set of thoughts or aphorisms on a given subject (as in the Kama Sutra, a treatise on love and courtship). Since there is no written record of Buddhist doctrine from the time of the Buddha, the canon of Buddhist literature brims with hundreds of such sutras which purport to reveal his true teaching.

The Lotus Sutra has a special place in the Buddhist canon. A lively if often confounding grab bag of parables and proclamations told in both prose and verse, it is rich in narrative pleasure and contains more braggadocio than a Donald Trump speech. (“The Buddha is the king,” we read at one point, “this sutra is his wife.”) Indeed, many scholars trace its self-promotional tone back to the era of its composition, when it had to establish itself within a crowded market of religious texts and sects in India. The nature of the Lotus Sutra’s influence is taken up by the scholar of Buddhism Donald S. Lopez Jr. in the latest in Princeton University Press’s excellent series on the “lives of great religious books.”

As with so many religious works from antiquity, the Sutra has a history shrouded in uncertainty. Even its authorship is a mystery. By the time it was composed in Sanskrit early in the first millennium, the Buddha had been dead for 500 years. His striking message, at once austere and compassionate, offered a vision of liberation resolutely free of mythological content. The Buddha’s eerily convincing diagnosis of the nature of human suffering and the way to transcend it had achieved a wide currency in India and had extended to China and Sri Lanka. But Buddhism had begun to break up into sects over divergent interpretations of the teaching.

The major schism was between the Hinayana and the Mahayana. The Hinayana school stressed the importance of monastic life as the only real path to liberation. Mahayana Buddhism, on the other hand, was much more worldly even in its quest for transcendence. Its hero was not the “arhat,” or the being who has attained nirvana, but the “bodhisattva,” the enlightened person who perceives the truth but stays behind in the world to help others across to the far shore of peace.

The Lotus Sutra is a classic—and cacophonous—Mahayana text. The book unfolds as a series of dialogues between the Buddha and his followers, many of them men of great spiritual prowess themselves. The text slowly and artfully builds to a revelation: that of the “saddharma,” or true dharma. The Buddha reveals to his interlocutors that the “threefold path” that he teaches in other texts—a somewhat arcane theory of different streams of learning and discipleship that open out paths to liberation—is actually something of a deception.

In truth, there is only a single Way. But “this Dharma is indescribable / Words must fall silent.” (A very lucid account of the possible nature of this vision, which the Buddha says cannot be formulated in language, can be found in Heinrich Zimmer’s 1952 book “Philosophies of India.) The Buddha is so far gone, he explains, that had he taught such a difficult doctrine, he would have made himself clear to precisely nobody. Instead, he used the path of “skillful means” to set people off on the path to transcendence, preaching to each person according to his estimate of their capacity for enlightenment.

With this master stroke, the Lotus Sutra makes the goal of liberation at once more mysterious and more practicable (and, conveniently, knocks out other sutras competing for the attention of the faithful). The ultimate goal, so elusive, seems almost unattainable, but this makes every teacher a student and every student part of a great, throbbing chain of learning. Indeed, following the Buddha, any teacher must think seriously not just about knowledge, but the right way to transmit it. In this way, the Lotus Sutra makes itself indispensable not just as a teaching, but as a tool of pedagogy. As Mr. Lopez writes: “Perhaps the central teaching of the Lotus Sutra is to teach the Lotus Sutra.”

The allure of Buddhism eventually faded in the land of its birth, where Hinduism was too vivid and well-established to give way to this more introspective ideology. But the Lotus Sutra and other key texts gradually took root in others lands and languages. To the raft of entertaining characters found in the text itself—peasants and princes, initiates and religious masters, the Buddha as both truth-teller and deceiver—Mr. Lopez’s book adds a cast of historical figures across two millennia united only by their passion for the book, including the 13th-century Japanese monk Nichiren, whose fire-and-brimstone message declaring all other Buddhist texts but the Lotus Sutra to be heretical earned him a long incarceration on a lonely island, and Gustave Flaubert.

The author focuses on two especially interesting figures, both of them translators. The first, the Buddhist monk Kumarajiva, lived in eastern India in the 4th century, and had the misfortune of being taken hostage by an invading Chinese general. Over long years as a prisoner, he picked up enough Chinese to translate the Lotus Sutra for the benefit of the Chinese emperor, already a devout Buddhist. Thus the Sutra took root in China, and spread slowly through the Far East.

Just as fascinating is the story of how the book arrived in the West. The Sutra was among a large cache of Buddhist manuscripts sent early in the 19th century to the French Sanskritist Eugène Burnouf by Brian Hodgson, an enterprising young officer of the British East India Company. Burnouf immediately set to translating it, noting among other things the book’s “discursive and very Socratic method of exposition.” His French version, published posthumously in 1852, made its way across the Atlantic, where it was picked up and circulated in translation by Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Transcendentalists, who regularly published scriptures from Asia in their magazine, the Dial.

Mr. Lopez’s book shows us that translators are the unsung heroes of religious, as much as literary, history. Here he has serviced the text with yet another sort of translation—this one to a general audience.

The Lotus Sutra is a rejection, observes Mr. Lopez, of the kind of nirvana “that is a solitary and passive state of eternal peace.” Rather, we are all travelers on a long road, even the enlightened ones among us; we cannot see through to the end right from the start and must begin with small acts of compassion and caring. The inspiring message of the Lotus Sutra is that buddhahood is immanent in all of us.

Published on January 10, 2017 15:30

December 16, 2015

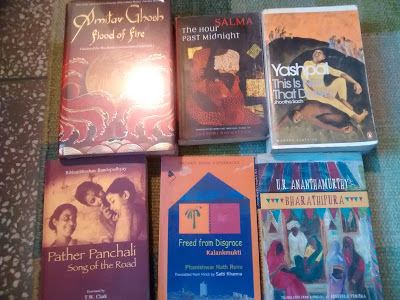

On Amitav Ghosh's Flood of Fire

Much like the ambitious speculators who appear so often in his Ibis Trilogy, Amitav Ghosh – or the narrator who answers to his name – resumes operations in Flood of Fire, the final book, having sunk all his narrative capital into a consignment that must now be carefully steered into a safe harbour. The reader knows that the panorama of characters from the first two books – the dispossessed Indian prince Neel Rattan Halder, the young American shipwright Zachary Reid, the wily Hindu accountant Baboo Nob Kissin Pander, the grizzled opium merchants Benjamin Burnham and Bahram Modi, the peasants and soldiers, the boatmen who rove the rivers of Calcutta and Canton and the vagrant lascars who traverse the ports of the Indian Ocean – are connected by a ship, the Ibis; a substance, opium; and an institution, the English East India Company.

Much like the ambitious speculators who appear so often in his Ibis Trilogy, Amitav Ghosh – or the narrator who answers to his name – resumes operations in Flood of Fire, the final book, having sunk all his narrative capital into a consignment that must now be carefully steered into a safe harbour. The reader knows that the panorama of characters from the first two books – the dispossessed Indian prince Neel Rattan Halder, the young American shipwright Zachary Reid, the wily Hindu accountant Baboo Nob Kissin Pander, the grizzled opium merchants Benjamin Burnham and Bahram Modi, the peasants and soldiers, the boatmen who rove the rivers of Calcutta and Canton and the vagrant lascars who traverse the ports of the Indian Ocean – are connected by a ship, the Ibis; a substance, opium; and an institution, the English East India Company. And by a force? In Sea of Poppies and River of Smoke, characters were repeatedly seen straining to grasp the reasons for the moral and material upheavals of their world, and the mystery of why they had come together. The Ibis, a former slave ship now requisitioned by a British merchant attached to the East India Company in Calcutta, became a microcosm of a rapidly changing world order: each character on his grim voyage to the colony of Mauritius offered his own interpretation of his destiny and ‘the delirium of the world’, but only the powerful were able to understand it. Among the Indian cast members, only the ambitious Parsi merchant from Bombay, Bahram Modi, could see through the tumult wrought by the opium trade on England, India and China. Flood of Fire, which draws the story out into the Chinese Opium War of 1840, brings the trilogy’s grand subject clearly into focus: capitalism and colonialism as invented, practised and justified across the ports and seaboards of the Indian Ocean in the 19th century by ‘Britannia’s all-seeing eye and all-grasping hand’. Opium, Ghosh suggests, was the substance that created the modern world, and he has set out to tell its epic story.

The dynamism and turbulence of the trade come across in the language of the novels, which is clamorously and sonorously inventive. Early in Sea of Poppies, Zachary, on his journey from America, is forced to change his ‘usual sailor’s menu of lobscouse, dandyfunk and chokedog, to a Laskari fare of karibat and kedgeree’: in these books characters consume not only each other’s cuisine, but their languages too. Different communities swap and transform elements of each other’s vocabulary. Many of the characters are not native English speakers: they speak Hindustani, Bhojpuri, Cantonese and lascar-lingo, and their attempts to communicate with the British, and British attempts to communicate with them, create a rich, lively and punning texture.

Power determines the new linguistic ‘normal’. The English of the soldiers, sahibs and memsahibs (or Burra BeeBees) in the cities, factories and garrisons of the East India Company reflects a desire to hold on to the world they have left behind, and to make sense of – and prove their interest in, or contempt for – the one they find themselves in. ‘Chuckmuckery’, they say, after the Hindi word for ‘glittering’, chakmak; or ‘dumbcow’, from the Hindi for ‘threaten’, dhamkao; or ‘tuncaw’, from the Hindi tankhaor salary. As they bend the strange world of India to their will, they attempt to bend the Indian language into something that sounds like their own, without seeing that they are also being shaped by it. One of the novel’s best puns, repeated so often that it becomes a leitmotif, is uttered by Catherine Burnham, the wife of the Ibis’s owner: ‘Surely you can see,’ she tells her lover, Zachary, ‘that it would not suit me at all to be a mystery’s mistress?’ A mistri, in Hindi, is a humble toolsman, which is how Zachary started out, but it’s the homonym that proves to be the more pertinent characteristic.

During the first two books, Catherine seemed the very incarnation of severe, corseted self-possession, BeeBee-style. Her husband, Benjamin Burnham, is typical of the Englishmen who have arrived in India with the East India Company. He is an agent not just of the Company’s flourishing opium trade, but also of the larger ideology of free trade as a whole, with its alluring new vocabulary of rivers of supply flowing towards vessels of demand, and of markets no longer constrained by morals but creating a new morality – even a new religion. ‘Jesus Christ is Free Trade,’ he insists, ‘and Free Trade is Jesus Christ.’ But now Burnham is in China, trying to break the blockade imposed by the Chinese emperor on the import of opium. When Zachary – the young, mixed-race American shipwright who appeared in Sea of Poppies delivering the Ibis to Burnham from Baltimore – receives a commission to repair another boat of Burnham’s, Mrs Burnham suddenly takes a keen interest in reforming him. Her reproving letters and insistence on private consultations soon reveal a pent-up passion of her own. Before they know it, the two are lovers and Zachary has been introduced to a world of feminine mystery and material wealth. When Burnham returns unexpectedly from Canton, the mystery is abruptly discarded, as his mistress had warned he would be, but love for Catherine has already led Zachary to covet a place in Mr Burnham’s world, and, crucially, to realise that this need not be a fantasy. For once, the winds of history are behind the sails of men like him.

One day, Zachary is taken by Mr Burnham’s generous gomusta, or accountant, Baboo Nob Kissin, to an opium auction held by the East India Company. (The Baboo, whose diligent caressing of ‘correct English’ recalls Hurree Babu in Kipling’s Kim, has his own agenda.) The spectacle is so grand, and the awe in which big traders like Mr.Burnham are held so seductive, that Zachary decides to invest the money bestowed on him by Mrs Burnham during their assignations in a small consignment of opium, to be taken to China alongside Mr.Burnham’s vast stock. Love’s labours have become a source of capital: Mrs Burnham has shown him his place in the world and set him on the road, should he have the nerve for it, to becoming a sahib. Zachary is no longer a mere mystery and an exuberant free trader in language – he speaks more languages than anyone else in the trilogy – but a Free Trader as Mr Burnham understands the term. Like Mr Burnham, Zachary has crossed the divide – the distinction is made by Fernand Braudel in his classic study, The Wheels of Commerce – from the market economy to capitalism, from the routine material life of an economy to the darker arts of speculation. It is almost like falling in love again. That night,

Zachary experienced spasms of anticipation that were no less intense than those that had seized him before his assignations with Mrs Burnham. It was as if the money that she had given him had suddenly taken on a new life: her coins were out there in the world, forging their own destiny, making secret assignations, colliding with others of their own kind – seducing, buying, spending, breeding, multiplying.

The hideous culmination of the cult of free trade is the Opium War of 1840, which has been anticipated from at least halfway through River of Smoke. Ghosh’s account is more or less faithful to history. With tea all the rage in England, the East India Company required a scarce and desirable commodity of its own in order to balance its trade with China, so created a vast market in China for Indian opium. With more and more Chinese men incapacitated by an addiction to ‘chasing the dragon’ (the exquisite scenes of opium-smoking in Ghosh’s story elicit pleasures to rival the narcotic ones), the authorities in Canton eventually declared the trade illegal. The distress and debt generated by this move reverberated back up the distribution and production chains to Calcutta and Bombay, and moved the powerful British merchants in Canton to lobby the British government to intercede. The result was a war which the economist Ha-Joon Chang describes in Bad Samaritans, his account of the deceits and delusions behind the idea of free trade, as ‘particularly shameful . . . even by the standards of 19th-century imperialism’.

By the time we reach the final act in Flood of Fire, Ghosh has laid the ground painstakingly for a sophisticated analysis of the politics of the war. Details of nautical and military manoeuvres are relayed with panache and present an unforgettable picture of the tumult of military order (“The noise too was overpowering, the sheer volume of it: the thudding of feet, the pounding of drums, the ‘Har-har-Mahadev’ battle-cry of the sepoys, and above all that, the whistle and shriek of shots passing overhead”). And there’s a sombre beauty to the British and Chinese descriptions of the war’s devastation (“All around them metal was clanging on metal, drowning out the cries of dying men”), as also to the narrator’s attention to his favoured few (“An unnameable grief came upon him then; falling to his knees he reached out to close the dead man’s eyes.”)

As in the previous books, some of the most dramatic moments involve characters who, having taken up the challenge posed by circumstances not accounted for by convention, realise that their very identity is being devastated in the process. We see Shireen, the widow of Bahram Modi and a woman who has never even left her house in Bombay without an escort, taking a ship out to Canton to try and recover her husband’s fortune. Soon she realises, with both alarm and pleasure, that ‘the journey ahead would entail much more than just a change of location: in order to arrive at her destination she would have to become a different person.’ (Her actions are also being determined by a principle which the feminist critic Malashri Lal calls ‘the law of the threshold’, according to which the lives of women in Indian novels change irreversibly when they cross the safe, but suffocating,threshold of their houses, and by implication their gender-defined roles, for the first time.)

And midway through the war, the reader also realises that Zachary’s amiable and empathetic nature has coarsened irredeemably, as power becomes more important to him than justice. ‘I am a man who wants more and more and more,’ he declares towards the close of the book, ‘a man who does not know the meaning of “enough”. Anyone who tries to thwart my desires is the enemy of my liberty and must expect to be treated as such.’

Over the course of the three books, one character stands out as possessing a level of intelligence and detachment on a par with the narrator’s, and it is to him that the trilogy’s greatest meditation on history is handed. He is Neel Rattan Halder, the Raja of Raskhali, a somewhat introverted sensualist, heir to the revenues from his family’s feudal estate and the profits from his father’s investment in Mr Burnham’s enterprise. In Sea of Poppies his wealth was confiscated by a British court in Calcutta and he was sentenced to several years in the penal colony of Mauritius. On his way, on board the Ibis, Neel jumped ship and eventually ended up in Canton under an assumed name, his truculent nature shaken by adventures he would never have sought out himself. In Flood of Fire, he is settled in Canton and works as a translator of English documents into Chinese. But he fears that the Chinese aren’t taking the British threat of war seriously enough, and believes that they will come to regret their assurance that a vast country can’t be shaken by a few foreign battleships. When the two sides finally meet in battle, it’s as if two ages are clashing, and Neel becomes both elegist of the old order and a chronicler of the energies of a new force in history:

He had never witnessed a battle before and was profoundly affected by what he saw. Thinking about it later he understood that a battle was a distillation of time: many years of preparation and decades of innovation and chance were squeezed into a clash of very short duration. And when it was over the impact radiated backwards and forwards through time, determining the future and even, in a sense, changing the past, or at least the general understanding of it. It astonished him that he had not recognised before the terrible power that was contained within these wrinkles in time – a power that could mould the lives of those who came afterwards for generation after generation . . . He understood then why Shias commemorate the Battle of Kerbala every year: it was an acknowledgement that just as the earth splits apart at certain moments, to create momentous upheavals that forever change the terrain, so do time and history.How was it possible that a small number of men, in the span of a few hours or minutes, could decide the fate of millions of people yet unborn? How was it possible that the outcome of those brief moments could determine who would rule whom, who would be rich or poor, master or servant, for generations to come?Nothing could be a greater injustice, yet such had been the reality ever since human beings first walked the earth.

Those familiar with Ghosh’s work will hear echoes here of his previous novels. From his very first book, his characters always seem to know that they are sailing not just on the ship of Time, but – which is a different thing – of History. Even as they search for meaning and agency in their own lives, they compare their situations and civilizations to others distant or disappeared; sometimes centuries pass in their mind’s eye as hours do in the lives of others.

But as Ghosh has learnt to withhold these meditations from his cerebral narrators and disperse them more freely and cunningly among his characters, so his books have come to exude not the fusty odours of the library, of the mind responding to a text or map at leisure, but rather the bracing air and even flood of fire of the greatest fiction, of the mind taking itself by surprise during a moment’s respite from the body’s labours. “Ben Yiju’s documents were mostly written in an unusual, hybrid language:” declares the narrator of In An Antique Land (1992), describing his twelfth-century Jewish merchant who is his subject, “one that has such an arcane sound to it that it might well be an entry in a book of Amazing Facts.” “Nobody knows, nobody can ever know, not even in memory, because there are moments in time that are not knowable:” declares the equally studious narrator of The Shadow Lines (1986), “nobody can ever know what it was like to be young and intelligent in the summer of 1939 in London or Berlin.” Compare these to the music of the spheres produced by the (in this case disembodied) narrator watching the Bihari peasant woman (and reluctant poppy-cultivator) Deeti in The Sea of Poppies as she undertakes the long voyage to Mauritius on board the Ibis:

As she was listening to the sighing of the sails, she became aware that there was a grain lodged under her thumbnail. It was a single poppy seed: prising it out, she rolled it between her fingers and raised her eyes, past the straining sails, to the star-filled vault above. On any other night she would have scanned the sky for the planet she had always thought to be the arbiter of her fate – but tonight her eyes dropped instead to the tiny sphere she was holding between her thumb and forefinger.

Published on December 16, 2015 04:38

September 29, 2015

The Indian Novel As An Agent of History

This essay was published earlier this month at India in Transition, a website run by the Center for Advanced Study on India at the University of Pennsylvania.

This essay was published earlier this month at India in Transition, a website run by the Center for Advanced Study on India at the University of Pennsylvania.It is a universally-acknowledged truth that human beings experience their lives as embedded not just in time, but in history. To interpret history, they employ a variety of instruments: personal experience and cultural memory, political ideology and historiography, even (and sometimes especially) myths and stories. Among these instruments, a somewhat late-arriving one in India – only 150 years old – is the novel.What is so noteworthy about the novel? It can be argued that as a form of story, let alone history, the novel does not enjoy great currency in India, for it is neither an indigenous form nor a mass one. Cinema has far greater popular appeal, and the stories and narrative conventions of epics like the Ramayana inform everyday life and moral reasoning much more than any novel (notwithstanding the apparent desire of nearly every Indian to write a novel, ideally a bestseller).Yet if the novel is indispensable to any reading of modern Indian history, that is because a preoccupation with Indian history is a thread running through the work of some of the greatest Indian novelists, across more than two dozen Indian languages and literary traditions. In the great diversity of narrative forms and interpretative cruxes generated by the Indian novel, there lies a wealth of wisdom about Indian history and, therefore, about how to live in the present time as an Indian and a South Asian, a modern of the twenty-first century and a third- or fourth-generation denizen of the often disorienting age of democracy.Consider Fakir Mohan Senapati’s enormously sly, satirical, and light-footed novel Six Acres and a Third , written in Odia in 1902 and only translated into English in 2006. The plot of Senapati’s novel revolves around a village landowner’s plot to usurp the small landholding of some humble weavers. But this is also the Indian village in the high noon of colonialism, and the first readers of Senapati’s story would have delighted in the narrator’s many potshots against new and perplexing British institutions, administered by a new ruling class of English-educated Indians. “Ask a new babu his grandfather’s father’s name, and he will hem and haw,” the narrator chirps. “But the names of the ancestors of England’s Charles the Third will readily roll off his tongue.”The story appears to be generating, then, an argument about history and political resistance. India must rid itself of its colonial masters because they have delegitimized many of the traditional knowledge systems and truths of Indian society, and in the process made the modern Indian self imitative and inauthentic. The argument persists in India today in debates about “westernization.”But this raises a new question: was traditional Indian village society itself very wise, just, or balanced? As the story progresses, we see that anti-colonial sentiments have not blinded the narrator to the need to subject his own side to the scrutiny of satire. When we hear that “the priest was very highly regarded in the village, particularly by the women,” and that “the goddess frequently appeared to him in his dreams and talked to him about everything,” the complacency and mystifications of Brahmanical Hinduism are also laid bare, as is the credulity about those who would place their faith in such an order.Senapati’s irony is effective not despite, but because of its double-sidedness. It leads to a point useful as much in our time as his own: criticism of a clearly marked-out “other” – to Indians in the early twentieth century, the British; to Hindu nationalists today, Muslims and Christians – often legitimizes a sweeping and complacent faith in one’s own worldview;the search for truth or meaning in history must remain a charade if not accompanied by the capacity for self-criticism. The novel’s implied argument is liberating not because it is comforting or inspiring, but precisely because it is disenchanted. Fiction itself shows us how human beings are fiction-making creatures, and must therefore take special care to scrutinize what they believe to be foundational truths.A different kind of novelistic irony – cosmic rather than comic – radiates from This Is Not That Dawn, the recent English translation of Hindi novelist Yashpal’s thousand-page magnum opus from the 1950s about Partition, Jhootha Sach (literally, The False Truth). Tracking the lives and loves of a brother and sister across the worlds of Lahore and New Delhi in the years both before and after Partition, Yashpal’s novel generates dozens of alternative views of that cataclysm from viewpoints male and female, Hindu and Muslim, Indian and Pakistani (even as these new identities come into being and crystallize), prospective and retrospective.Here is history on the grand scale – individual, national, human, all at the same time. Each character’s position or dilemma carries its own distinctive charge of hope, memory, conviction, doubt, faith, naïveté, prejudice, and fatalism; a vast spectacle of human beings swimming valiantly with and against the tides of history. If the narrator himself has something to say about the logic or validity of the breaking up of India, it remains parcelled out among the characters, and must be intuited by the reader.But in fact, the feeling we take away from Yashpal’s novel is not that of an entirely tragic story. Of course, Partition destroyed a particular shared and historically stable, if unconceptualized, sense of what it meant to be Indian. But as we perceive from the quest of the protagonist, Jaidev Puri, to start his own newspaper based on the idea of secular reason, what it means to be Indian would, in a new democratic and secular republic, have entailed building upon a new foundation in any case. At certain junctures in history, tragedy and progress may be inseparably mingled.As these examples show, the work of novels is not confined to mere representation of historical realities, although this is where they may start. Rather, a novel may be a creative intervention in history in its own right – an actual agent of history, passing on to the reader who passes through its narrative field both its diagnostic and visionary powers. Indeed, from Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay to U. R. Ananthamurthy, Bankimchandra Chatterjee to Kiran Nagarkar, Qurratulain Hyder to Salma, Phanishwarnath Renu to Amitav Ghosh, novelists have generated some of the most layered and sophisticated visions of Indian history produced in the last two centuries. Yet as a group, they fall into no school or political camp. What unites them is their ability to illuminate the particular historical crux on which they focus, such as the tension in Ananthamurthy’s novels between the hierarchical imperatives of Hinduism and the egalitarian urges of democracy.The novel form possesses certain advantages over other forms of discursive prose as a lens on history. There’s the persuasive power and ambiguity of a story, which may be read in many ways and asks for the partnership of the reader in the unpacking of its meanings. The freedom to rove in spaces of the past that we cannot access by means other than that of the imagination. The potential to think not in a straight line but dialectically in exchanges between characters, or switches in perspective between the narrator and the characters. All of these make the space of the novel a particularly fertile ground for historical thinking.In fact, when they are themselves reinserted into the canvas of Indian history, the projects of the Indian novel and that of Indian democracy – both fairly new forms in Indian history – appear uncannily similar, and perhaps similarly unfinished. As Indian democracy has, over the past seven decades, sought to fashion a new social contract in a deeply hierarchical civilization, so the great Indian novel has attempted to not just find but to also form a new kind of reader/citizen, alive to both the iniquities and the redemptive potential of Indian history.

Published on September 29, 2015 07:10

October 5, 2014

On DR Nagaraj's Listening To The Loom

The words "modern India" are used today to describe a vast nation-state of over a billion people, but they also imply a particular trajectory of history. They refer to an ancient, ethnically and culturally diverse civilization that was colonized from the eighteenth century onwards, that developed a native intelligentsia that eventually deployed against British colonialism ideas of nationhood and liberty adapted from thought currents in the West, and that in 1947 won independence and became a nation-state ambitiously committed to democracy and secularism.

The words "modern India" are used today to describe a vast nation-state of over a billion people, but they also imply a particular trajectory of history. They refer to an ancient, ethnically and culturally diverse civilization that was colonized from the eighteenth century onwards, that developed a native intelligentsia that eventually deployed against British colonialism ideas of nationhood and liberty adapted from thought currents in the West, and that in 1947 won independence and became a nation-state ambitiously committed to democracy and secularism.But if much has been gained by the ascent, over three centuries, of modern political ideals and global thought-systems in India, much, too, about the precolonial Indian past has become obscure, or entirely fallen away from view. In the new beginnings either forced upon the country in recent centuries or else self-consciously fashioned at home, these older knowledge-systems seem to have no place. To put it another way, in the twenty-first century's speeded-up time and vast platter of choices, the past seems to have become shorter. What might we do to prevent ourselves from completely becoming the prisoners of our own categories of time and place?

The Indian intellectual DR Nagaraj, a dazzling and eclectic thinker who taught briefly in America at the University of Chicago in the nineties before he died tragically young at the age of 44, is best-known forhis book of essays on Mahatma Gandhi and BR Ambedkar, two intellectual titans of the Indian twentieth century who often took opposing positions on the great issues of their day, such as the caste system and untouchability. But Nagaraj was also possessed by a desire not just to see the Indian past through the lenses of the present, but also to turn history around and inspect the present through the lenses of the past. “If the methods and philosophical positions of present times are fit and useful to analyse the formulations of several kinds of pre-modern eras, the reverse should also be true,” he writes. Genuinely bilingual -- he wrote in both Kannada, one of the major languages of the Indian south, and in English -- he possessed the resources to carry this project through. Many of Nagaraj's ideas about how the dozens of distant Indian pasts could be brought to bear productively upon the present have just become available in a posthumously published book of essays, put together by his friends, colleagues, and students, called Listening To The Loom.

Although the book is often difficult going, reading it is like being taken on a whirlwind tour of Indian intellectual history, the kind of journey that nobody seriously interested in India should deny himself. I stayed up late into the night with it for several days, stimulated by sense a contact with a mind that seemed to be living in several centuries at the same time. The effect of reading Nagaraj has been described very well by the Indian historian Ananja Vajpeyi, who was briefly his student at Chicago:

DR could teach us about Gandhi, Ambedkar and Nehru, in many ways India’s archetypal modernists, all the while speaking in a style that suggested that even today, the Buddha was delivering sermons in Sarnath, and the classical doctrines of Nayyayikas

and Buddhists, Mimansakas and Advaitins, Carvakas and Jainas, Sufis and Sikhs, were creating the pleasant hum and hubbub of an Indic intellectual world. My hunch is that DR identified, in a personal way, with the protagonists he constantly returned to: the Buddha, who walked away from worldly attachments, only to find it supremely difficult to actually detach himself; Nagarjuna, a Brahmin who turned Buddhist, the South Indian from Andhra whose texts brought Buddhism to Tibet and China; Ambedkar, the modernist obsessed with premodernity; Gandhi, who had to wrestle as hard with his own indefatigable appetites as he did with the mighty British Empire.

DR’s catholicity, his capacious hunger to master Pali and Sanskrit, old Kannada and classical Tamil, Continental philosophy and postmodern literary theory, challenged every stereotype about radical intellectual politics.

Nagaraj’s painstaking and perceptive editor, Prithvi Datta Chandra Shobhi, who's tenured at San Francisco State University, compares him to that of the ancient Indian pauranika: “the storyteller who organises the knowledge and wisdom of a culture,” and guards against the slide into intellectual amnesia. But what exactly did Nagaraj think Indians were losing sight of?

For Nagaraj, as for several other prominent modern Indian thinkers working in different modes (whether Jawaharlal Nehru in his book The Discovery of India, or the framers of the Indian constitution) the first fact of Indian history was its pluralism, its diversity of viewpoints and knowledge systems – some exceedingly arcane, but nevertheless philosophically rigorous and linguistically rich – humming in dialogue or tension with one another. This history meant that no one religion, ethnic group, or languagecould enjoy a specially privileged place in the new Indian nation.

But at the same time, the modern nation-state, with its vast hunger for centralization and homogenization, invariably tilts towards a public sphere composed of majorities and minorities, insiders and outsiders, us and them – or what Nagaraj calls “identity narratives of the religious-nationalist kind”. Almost every nation-state that has emerged from the shadow of colonialism continues to wrestle with this problem.

This majoritarian tendency is seen in modern India in the right-wing Hindu project that wishes to pummel Hinduism into a unified field and to represent minorities (Muslims, tribals, agitating lower-caste groups) as misguided, unpatriotic, or aberrant. (Both aspects of this tendency can be found in a rant by the Indian politician Subramanian Swamy last year.) Nagaraj’s brief, tenchant critique of the Hindu right-wing movement’s use of the figure of Rama – the hero of the ancient Indian epic the Ramayana – as a symbol for its political aspirations will have to serve here as a representative instance of his own method. The movement reached its apotheosis in 1992, when Hindu agitators destroyed a mosque, the Babri Masjid, in the north Indian town of Ayodhya, since the site was considered the birthplace of the historical Rama. (An excellent eyewitness account of the sacking of the Babri Masjid and a meditation on its fallout in Indian life can be found in the Australian foreign correspondent Christopher Kremmer's book Inhaling The Mahatma.)

But this fixing of Rama in both history and geography, argues Nagaraj, elides the hundreds of other “sightings” of Ram and the other major protagonists of the Ramayana reported in legends from all across India and not only the north. The power of Rama in Indian history, as expressed in its art and its legends, was that he was not “there”, speaking from remote Ayodhya, but always “here”, somewhere close to home. (Diana Eck’s magisterial recent book India: A Sacred Geography illuminates Hinduism’s persistent instinct for duplication of global stories in local contexts).

But with Hindu nationalism, says Nagaraj, “history and faith are being made to share the same bed” -- somewhat like with creationism in America. What might be an antidote to such divisive readings of the Ramayana? For Nagaraj, the answer lay in not just a scolding based on the ideals of the Indian constitution (a point of view which sounds patronising to many right-wing Hindus), but a turn instead of the many “folk” Ramayanas of India, which often poke fun at the central characters of the epic, and see their stories as aesthetically malleable structures to be continuously reinterpreted, not set down in stone. For Nagaraj, “the recovery of difference is an effective way of overcoming those threats posed by the essentialist use of symbols.” The pluralism of the Indian constitution might be seen as just the codification, in the modern language of rights, secularism, and democracy, of the natural pluralism of Indian history.

In a tribute to Nagaraj shortly after his death, the scholars Sheldon Pollock and Carol Appadurai Breckinbridge offered an assessment not just of the range of Nagaraj's intellectual gifts but also of the diverse, and sometimes disquieting, life experiences he brought to his work. Just as Charles Dickens as a boy had done time in a blacking factory, so too Nagaraj, born in a notionally free India, had as a boy spent some time weaving in bonded labour. Pollock and Breckinbridge wrote:

When D. R. became a visiting professor at the University of Chicago in 1996, he had gained a reputation as one of the leading cultural critics in India, and perhaps the foremost thinker of the politics of cultural choice among those he would refer to as historically humiliated communities, including dalits (those formerly called untouchables) and artisanal castes known as shudras. If this were all D. R. had to give, it would have been gift enough. But D. R. approached the problem of subaltern cultural choice from a perspective broadened not only by familiarity with contemporary metropolitan thought but also by profound study of the living cultures of rural India and of the precolonial past. It was especially in that past -- the fact that so many South Asian intellectuals no longer had access to it was for D. R. an enduring catastrophe of colonialism -- that he found important resources to recover and theorize. And he did this in a spirit neither of antiquarianism nor indigenism. D. R. understood that social and political justice cannot be secured without reasoned critique, and that the instruments of critique in postcolonial India had to be forged anew from an alloy that included precolonial Indian thought and culture -- but only after being subjected themselves to critical inspection. In exploring these resources he showed the remarkable intellectual reach and curiosity that enabled him to speak across every disciplinary boundary and to explore an astonishing range of conceptual and ethical possibilities.

To put it another way, while many prominent modern Indian thinkers have sought to expand Indian pluralism from above, in dialogue with ideas from the West, Nagaraj sought to expand Indian pluralism from below by sifting through the best of India's native traditions and recovering their vocabulary and concepts. The Clay Sanskrit Library (now the Murty Classical Library), an ambitious new Indic publishing project aiming "to make available the great literary works of India from the past two millennia in scholarly yet accessible translations", would have excited Nagaraj greatly as just the kind of gateway to the past that he tried to supply in his essays. One of the things that we most closely associate with the condition of being modern is the range of choices guaranteed to us in relationships, vocations, consumer goods. Through a book like *Listening To The Loom*, we see that what we are given as moderns is also an unprecedented ability to transcend our historical moment and inhabit the pasts from which our world has emerged.

Published on October 05, 2014 19:57

March 19, 2014

On DR Nagaraj's Listening To The Loom

>This essay was first published on Bloomberg View as "Sifting India's Present Through Its Deepest Past"

The words "modern India" are used today to describe a vast nation-state of over a billion people, but they also imply a particular trajectory of history. They refer to an ancient, ethnically and culturally diverse civilization that was colonized from the eighteenth century onwards, that developed a native intelligentsia that eventually deployed against British colonialism ideas of nationhood and liberty adapted from thought currents in the West, and that in 1947 won independence and became a nation-state ambitiously committed to democracy and secularism. But if much has been gained by the ascent, over three centuries, of modern political ideals and global thought-systems in India, much, too, about the precolonial Indian past has become obscure, or entirely fallen away from view. In the new beginnings either forced upon the country in recent centuries or else self-consciously fashioned at home, these older knowledge-systems seem to have no place. To put it another way, in the twenty-first century's speeded-up time and vast platter of choices, the past seems to have become shorter. What might we do to prevent ourselves from completely becoming the prisoners of our own categories of time and place?

The words "modern India" are used today to describe a vast nation-state of over a billion people, but they also imply a particular trajectory of history. They refer to an ancient, ethnically and culturally diverse civilization that was colonized from the eighteenth century onwards, that developed a native intelligentsia that eventually deployed against British colonialism ideas of nationhood and liberty adapted from thought currents in the West, and that in 1947 won independence and became a nation-state ambitiously committed to democracy and secularism. But if much has been gained by the ascent, over three centuries, of modern political ideals and global thought-systems in India, much, too, about the precolonial Indian past has become obscure, or entirely fallen away from view. In the new beginnings either forced upon the country in recent centuries or else self-consciously fashioned at home, these older knowledge-systems seem to have no place. To put it another way, in the twenty-first century's speeded-up time and vast platter of choices, the past seems to have become shorter. What might we do to prevent ourselves from completely becoming the prisoners of our own categories of time and place?

The Indian intellectual DR Nagaraj, a dazzling and eclectic thinker who taught briefly in America at the University of Chicago in the nineties before he died tragically young at the age of 44, is best-known for his book of essays on Mahatma Gandhi and BR Ambedkar, two intellectual titans of the Indian twentieth century who often took opposing positions on the great issues of their day, such as the caste system and untouchability.

But Nagaraj was also possessed by a desire not just to see the Indian past through the lenses of the present, but also to turn history around and inspect the present through the lenses of the past. “If the methods and philosophical positions of present times are fit and useful to analyse the formulations of several kinds of pre-modern eras, the reverse should also be true,” he writes. Genuinely bilingual -- he wrote in both Kannada, one of the major languages of the Indian south, and in English -- he possessed the resources to carry this project through. Many of Nagaraj's ideas about how the dozens of distant Indian pasts could be brought to bear productively upon the present have just become available in a posthumously published book of essays, put together by his friends, colleagues, and students, called Listening To The Loom.

Although the book is often difficult going, reading it is like being taken on a whirlwind tour of Indian intellectual history, the kind of journey that nobody seriously interested in India should deny himself. I stayed up late into the night with it for several days, stimulated by sense a contact with a mind that seemed to be living in several centuries at the same time. The effect of readingNagaraj has been described very well by the Indian historian Ananja Vajpeyi, who was briefly his student at Chicago:

I don't know about you, but I'd certainly like to know what it's like to be a Mimansaka or an Advaitin. Nagaraj’s painstaking and perceptive editor, Prithvi Datta Chandra Shobhi, who's tenured at San Francisco State University, compares him to that of the ancient Indian pauranika: “the storyteller who organises the knowledge and wisdom of a culture,” and guards against the slide into intellectual amnesia. But what exactly did Nagaraj think Indians were losing sight of?

For Nagaraj, as for several other prominent modern Indian thinkers working in different modes (whether Jawaharlal Nehru in his book The Discovery of India, or the framers of the Indian constitution) the first fact of Indian history was its pluralism, its diversity of viewpoints and knowledge systems – some exceedingly arcane, but nevertheless philosophically rigorous and linguistically rich – humming in dialogue or tension with one another. This history meant that no one religion, ethnic group, or language could enjoy a specially privileged place in the new Indian nation.

But at the same time, the modern nation-state, with its vast hunger for centralization and homogenization, invariably tilts towards a public sphere composed of majorities and minorities, insiders and outsiders, us and them – or what Nagaraj calls “identity narratives of the religious-nationalist kind”. Almost every nation-state that has emerged from the shadow of colonialism continues to wrestle with this problem.

This majoritarian tendency is seen in modern India in the right-wing Hindu project that wishes to pummel Hinduism into a unified field and to represent minorities (Muslims, tribals, agitating lower-caste groups) as misguided, unpatriotic, or aberrant. (Both aspects of this tendency can be found in a rant by the Indian politician Subramanian Swamy last year.) Nagaraj’s brief, tenchant critique of the Hindu right-wing movement’s use of the figure of Rama – the hero of the ancient Indian epic the Ramayana – as a symbol for its political aspirations will have to serve here as a representative instance of his own method.

The movement reached its apotheosis in 1992, when Hindu agitators destroyed a mosque, the Babri Masjid, in the north Indian town of Ayodhya, since the site was considered the birthplace of the historical Rama. (An excellent eyewitness account of the sacking of the Babri Masjid and a meditation on its fallout in Indian life can be found in the Australian foreign correspondent Christopher Kremmer's book Inhaling The Mahatma.)

But this fixing of Rama in both history and geography, argues Nagaraj, elides the hundreds of other “sightings” of Ram and the other major protagonists of the Ramayana reported in legends from all across India and not only the north. The power of Rama in Indian history, as expressed in its art and its legends, was that he was not “there”, speaking from remote Ayodhya, but always “here”, somewhere close to home. (Diana Eck’s magisterial recent book India: A Sacred Geography illuminates Hinduism’s persistent instinct for duplication of global stories in local contexts).

But with Hindu nationalism, says Nagaraj, “history and faith are being made to share the same bed” -- somewhat like with creationism in America. What might be an antidote to such divisive readings of the Ramayana? For Nagaraj, the answer lay in not just a scolding based on the ideals of the Indian constitution (a point of view which sounds patronising to many right-wing Hindus), but a turn instead of the many “folk” Ramayanas of India, which often poke fun at the central characters of the epic, and see their stories as aesthetically malleable structures to be continuously reinterpreted, not set down in stone. For Nagaraj, “the recovery of difference is an effective way of overcoming those threats posed by the essentialist use of symbols.” Thepluralism of the Indian constitution might be seen as just the codification, in the modern language of rights, secularism, and democracy, of the natural pluralism of Indian history.

In a tribute to Nagaraj shortly after his death, the scholars Sheldon Pollock and Carol Appadurai Breckinbridge offered an assessment not just of the range of Nagaraj's intellectual gifts but also of the diverse, and sometimes disquieting, life experiences he brought to his work. Just as Charles Dickens as a boy had done time in a blacking factory, so too Nagaraj, born in a notionally free India, had as a boy spent some time weaving in bonded labour. Pollock and Breckinbridge wrote:

To put it another way, while many prominent modern Indian thinkers have sought to expand Indian pluralism from above, in dialogue with ideas from the West, Nagaraj sought to expand Indian pluralism from below by sifting through the best of India's native traditions and recovering their vocabulary and concepts. The Clay Sanskrit Library (now the Murty Classical Library), an ambitious new Indic publishing project aiming "to make available the great literary works of India from the past two millennia in scholarly yet accessible translations", would have excited Nagaraj greatly as just the kind of gateway to the past that he tried to supply in his essays.

One of the things that we most closely associate with the condition of being modern is the range of choices guaranteed to us in relationships, vocations, consumer goods. Through a book like *Listening To The Loom*, we see that what we are given as moderns is also an unprecedented ability to transcend our historical moment and inhabit the pasts from which our world has emerged.

The words "modern India" are used today to describe a vast nation-state of over a billion people, but they also imply a particular trajectory of history. They refer to an ancient, ethnically and culturally diverse civilization that was colonized from the eighteenth century onwards, that developed a native intelligentsia that eventually deployed against British colonialism ideas of nationhood and liberty adapted from thought currents in the West, and that in 1947 won independence and became a nation-state ambitiously committed to democracy and secularism. But if much has been gained by the ascent, over three centuries, of modern political ideals and global thought-systems in India, much, too, about the precolonial Indian past has become obscure, or entirely fallen away from view. In the new beginnings either forced upon the country in recent centuries or else self-consciously fashioned at home, these older knowledge-systems seem to have no place. To put it another way, in the twenty-first century's speeded-up time and vast platter of choices, the past seems to have become shorter. What might we do to prevent ourselves from completely becoming the prisoners of our own categories of time and place?

The words "modern India" are used today to describe a vast nation-state of over a billion people, but they also imply a particular trajectory of history. They refer to an ancient, ethnically and culturally diverse civilization that was colonized from the eighteenth century onwards, that developed a native intelligentsia that eventually deployed against British colonialism ideas of nationhood and liberty adapted from thought currents in the West, and that in 1947 won independence and became a nation-state ambitiously committed to democracy and secularism. But if much has been gained by the ascent, over three centuries, of modern political ideals and global thought-systems in India, much, too, about the precolonial Indian past has become obscure, or entirely fallen away from view. In the new beginnings either forced upon the country in recent centuries or else self-consciously fashioned at home, these older knowledge-systems seem to have no place. To put it another way, in the twenty-first century's speeded-up time and vast platter of choices, the past seems to have become shorter. What might we do to prevent ourselves from completely becoming the prisoners of our own categories of time and place? The Indian intellectual DR Nagaraj, a dazzling and eclectic thinker who taught briefly in America at the University of Chicago in the nineties before he died tragically young at the age of 44, is best-known for his book of essays on Mahatma Gandhi and BR Ambedkar, two intellectual titans of the Indian twentieth century who often took opposing positions on the great issues of their day, such as the caste system and untouchability.

But Nagaraj was also possessed by a desire not just to see the Indian past through the lenses of the present, but also to turn history around and inspect the present through the lenses of the past. “If the methods and philosophical positions of present times are fit and useful to analyse the formulations of several kinds of pre-modern eras, the reverse should also be true,” he writes. Genuinely bilingual -- he wrote in both Kannada, one of the major languages of the Indian south, and in English -- he possessed the resources to carry this project through. Many of Nagaraj's ideas about how the dozens of distant Indian pasts could be brought to bear productively upon the present have just become available in a posthumously published book of essays, put together by his friends, colleagues, and students, called Listening To The Loom.

Although the book is often difficult going, reading it is like being taken on a whirlwind tour of Indian intellectual history, the kind of journey that nobody seriously interested in India should deny himself. I stayed up late into the night with it for several days, stimulated by sense a contact with a mind that seemed to be living in several centuries at the same time. The effect of readingNagaraj has been described very well by the Indian historian Ananja Vajpeyi, who was briefly his student at Chicago:

DR could teach us about Gandhi, Ambedkar and Nehru, in many ways India’s archetypal modernists, all the while speaking in a style that suggested that even today, the Buddha was delivering sermons in Sarnath, and the classical doctrines of Nayyayikas and Buddhists, Mimansakas and Advaitins, Carvakas and Jainas, Sufis and Sikhs, were creating the pleasant hum and hubbub of an Indic intellectual world. My hunch is that DR identified, in a personal way, with the protagonists he constantly returned to: the Buddha, who walked away from worldly attachments, only to find it supremely difficult to actually detach himself; Nagarjuna, a Brahmin who turned Buddhist, the South Indian from Andhra whose texts brought Buddhism to Tibet and China; Ambedkar, the modernist obsessed with premodernity; Gandhi, who had to wrestle as hard with his own indefatigable appetites as he did with the mighty British Empire.

DR’s catholicity, his capacious hunger to master Pali and Sanskrit, old Kannada and classical Tamil, Continental philosophy and postmodern literary theory, challenged every stereotype about radical intellectual politics.

I don't know about you, but I'd certainly like to know what it's like to be a Mimansaka or an Advaitin. Nagaraj’s painstaking and perceptive editor, Prithvi Datta Chandra Shobhi, who's tenured at San Francisco State University, compares him to that of the ancient Indian pauranika: “the storyteller who organises the knowledge and wisdom of a culture,” and guards against the slide into intellectual amnesia. But what exactly did Nagaraj think Indians were losing sight of?

For Nagaraj, as for several other prominent modern Indian thinkers working in different modes (whether Jawaharlal Nehru in his book The Discovery of India, or the framers of the Indian constitution) the first fact of Indian history was its pluralism, its diversity of viewpoints and knowledge systems – some exceedingly arcane, but nevertheless philosophically rigorous and linguistically rich – humming in dialogue or tension with one another. This history meant that no one religion, ethnic group, or language could enjoy a specially privileged place in the new Indian nation.

But at the same time, the modern nation-state, with its vast hunger for centralization and homogenization, invariably tilts towards a public sphere composed of majorities and minorities, insiders and outsiders, us and them – or what Nagaraj calls “identity narratives of the religious-nationalist kind”. Almost every nation-state that has emerged from the shadow of colonialism continues to wrestle with this problem.

This majoritarian tendency is seen in modern India in the right-wing Hindu project that wishes to pummel Hinduism into a unified field and to represent minorities (Muslims, tribals, agitating lower-caste groups) as misguided, unpatriotic, or aberrant. (Both aspects of this tendency can be found in a rant by the Indian politician Subramanian Swamy last year.) Nagaraj’s brief, tenchant critique of the Hindu right-wing movement’s use of the figure of Rama – the hero of the ancient Indian epic the Ramayana – as a symbol for its political aspirations will have to serve here as a representative instance of his own method.

The movement reached its apotheosis in 1992, when Hindu agitators destroyed a mosque, the Babri Masjid, in the north Indian town of Ayodhya, since the site was considered the birthplace of the historical Rama. (An excellent eyewitness account of the sacking of the Babri Masjid and a meditation on its fallout in Indian life can be found in the Australian foreign correspondent Christopher Kremmer's book Inhaling The Mahatma.)

But this fixing of Rama in both history and geography, argues Nagaraj, elides the hundreds of other “sightings” of Ram and the other major protagonists of the Ramayana reported in legends from all across India and not only the north. The power of Rama in Indian history, as expressed in its art and its legends, was that he was not “there”, speaking from remote Ayodhya, but always “here”, somewhere close to home. (Diana Eck’s magisterial recent book India: A Sacred Geography illuminates Hinduism’s persistent instinct for duplication of global stories in local contexts).

But with Hindu nationalism, says Nagaraj, “history and faith are being made to share the same bed” -- somewhat like with creationism in America. What might be an antidote to such divisive readings of the Ramayana? For Nagaraj, the answer lay in not just a scolding based on the ideals of the Indian constitution (a point of view which sounds patronising to many right-wing Hindus), but a turn instead of the many “folk” Ramayanas of India, which often poke fun at the central characters of the epic, and see their stories as aesthetically malleable structures to be continuously reinterpreted, not set down in stone. For Nagaraj, “the recovery of difference is an effective way of overcoming those threats posed by the essentialist use of symbols.” Thepluralism of the Indian constitution might be seen as just the codification, in the modern language of rights, secularism, and democracy, of the natural pluralism of Indian history.

In a tribute to Nagaraj shortly after his death, the scholars Sheldon Pollock and Carol Appadurai Breckinbridge offered an assessment not just of the range of Nagaraj's intellectual gifts but also of the diverse, and sometimes disquieting, life experiences he brought to his work. Just as Charles Dickens as a boy had done time in a blacking factory, so too Nagaraj, born in a notionally free India, had as a boy spent some time weaving in bonded labour. Pollock and Breckinbridge wrote:

When D. R. became a visiting professor at the University of Chicago in 1996, he had gained a reputation as one of the leading cultural critics in India, and perhaps the foremost thinker of the politics of cultural choice among those he would refer to as historically humiliated communities, including dalits (those formerly called untouchables) and artisanal castes known as shudras. If this were all D. R. had to give, it would have been gift enough. But D. R. approached the problem of subaltern cultural choice from a perspective broadened not only by familiarity with contemporary metropolitan thought but also by profound study of the living cultures of rural India and of the precolonial past. It was especially in that past -- the fact that so many South Asian intellectuals no longer had access to it was for D. R. an enduring catastrophe of colonialism -- that he found important resources to recover and theorize. And he did this in a spirit neither of antiquarianism nor indigenism. D. R. understood that social and political justice cannot be secured without reasoned critique, and that the instruments of critique in postcolonial India had to be forged anew from an alloy that included precolonial Indian thought and culture -- but only after being subjected themselves to critical inspection. In exploring these resources he showed the remarkable intellectual reach and curiosity that enabled him to speak across every disciplinary boundary and to explore an astonishing range of conceptual and ethical possibilities.

To put it another way, while many prominent modern Indian thinkers have sought to expand Indian pluralism from above, in dialogue with ideas from the West, Nagaraj sought to expand Indian pluralism from below by sifting through the best of India's native traditions and recovering their vocabulary and concepts. The Clay Sanskrit Library (now the Murty Classical Library), an ambitious new Indic publishing project aiming "to make available the great literary works of India from the past two millennia in scholarly yet accessible translations", would have excited Nagaraj greatly as just the kind of gateway to the past that he tried to supply in his essays.

One of the things that we most closely associate with the condition of being modern is the range of choices guaranteed to us in relationships, vocations, consumer goods. Through a book like *Listening To The Loom*, we see that what we are given as moderns is also an unprecedented ability to transcend our historical moment and inhabit the pasts from which our world has emerged.

Published on March 19, 2014 00:20

October 10, 2013

Arzee the Dwarf in America

Arzee the Dwarf is published in America this week by the New York Review of Books as part of their new e-book imprint of contemporary novels from around the world, NYRBLit.

Arzee the Dwarf is published in America this week by the New York Review of Books as part of their new e-book imprint of contemporary novels from around the world, NYRBLit.If you'd like to buy it to read on your Kindle, you can do so off the NYRB page or at Amazon.

The book is also available in German and in Spanish.

Published on October 10, 2013 19:09

April 18, 2013

Sadat Hasan Manto's Bombay Stories

This essay appeared last month in The National.

The short-story writer Saadat Hasan Manto (1912-1955) deserves to be thought of as the patron saint of modern South Asian fiction for at least three reasons.

The short-story writer Saadat Hasan Manto (1912-1955) deserves to be thought of as the patron saint of modern South Asian fiction for at least three reasons.

First, Manto was personally and artistically impacted, in a way that he transformed into enduring narrative prose, by the massive cataclysm of history that was the partition of colonial India in 1947 into two nation states, the Hindu-majority India and the Muslim-majority Pakistan. The decision sparked off the largest two-way migration in history, with millions of Hindus and Sikhs in what was suddenly Pakistan crossing into India and millions of Muslims in what was now a smaller India attempting to flee to Pakistan. Both sides leapt at each other’s throats on the long, strife-torn route, generating a bloodbath – and more lastingly, memories that were passed down for generations afterwards – that may take hundreds of years to heal.

This event generated the enduring politics of distrust between the two great powers of the subcontinent, which between them account for more than a quarter of the world’s population today. What Manto wrote then in the light of what he had known, heard or witnessed – and what he did with this material artistically, within the four walls of his own independence as a writer of fiction – make him an eerie and thrilling writer to this day.

Second, Manto’s daring and iconoclastic writing served as a kind of declaration of independence from the main narrative tenets and orthodoxies of his times, which was that fiction should be “socially relevant” in its content, that it locate the personal within the larger realm of the public sphere, and that it deal coyly and euphemistically – or at best metaphorically – with the subject of bodily functions. Manto was in his lifetime repeatedly charged by his critics (many of them writers themselves) with obscenity, and was even taken to court for what was seen as the outrageous licentiousness depicted in his work.

But what his critics saw as a determined emphasis on the bawdy,Manto merely understood to be a determined emphasis on the body – as a site for pleasure and violence, trust and treachery, a house for yearnings of mind and spirit as well as its own longings. The world of the prostitutes, pimps, waifs, wastrels and debauchees that he wrote about in story after story was a universe that existed in reality – as much a centre of Bombay (now Mumbai) as the film world or the world of polite society – and was stratified and impacted by religion, politics, ideology, migration and economics as interestingly as any middle-class or radical world.

The current of defiance embodied by Manto is one of literature’s most necessary currents; its spirit was given voice by the French-Arabic writer Tahar Ben Jelloun at the Jaipur Literature Festival earlier this year when he remarked, bitingly, of censorship, “What bothers censorship is the representation of reality and not reality itself.” To Manto, the writer must think through every sphere of human life, including one’s private life. If he is the frankest sensualist in Indian literature, it is because he knows (as did the 18th-century Italian adventurer Giacomo Casanova in his magnificent 12-volume autobiography The Story of My Life) that sensuality is not without its own rules or ethical codes. For this reason, he speaks as powerfully to the 21st century as he did to his own.