Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog, page 70

January 9, 2013

Toward a More Badass History

We probably should have seen this coming:

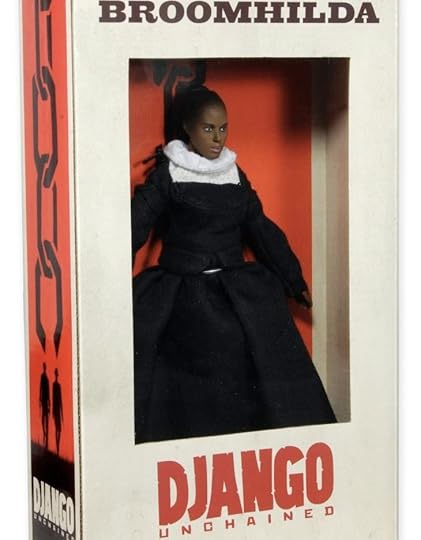

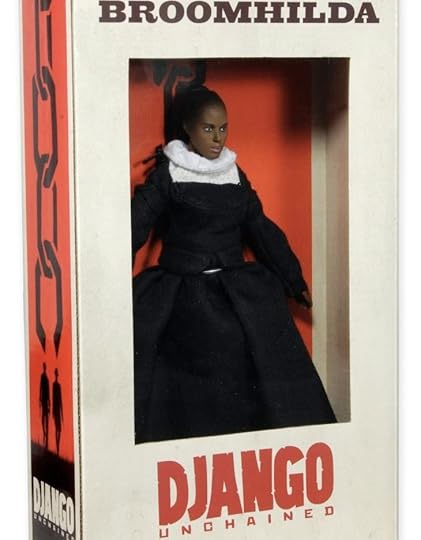

Last fall, the National Entertainment Collectibles Association, Inc. (NECA), in tandem with the Weinstein Company, announced a full line of consumer products based on characters from the movie. First up are pose-able eight-inch action figures with tailored clothing, weaponry, and accessories in the likeness of characters played by Foxx, Kerry Washington, Samuel L. Jackson, Leonardo DiCaprio, James Remar and Christoph Waltz.

The dolls are currently on sale via Amazon.com. A press release announcing the deal stated that the line was similar to the retro toy lines that helped define the licensed action-figure market in the 1970s and that the collection will include a full apparel and accessories line. At the time of the announcement, NECA president Joel Weinshanker said the company was "very excited to bring the stellar cast of Django to life and honored to be working with another Tarantino masterpiece."

Action figures for Tarantino films Kill Bill Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 may have been better suited for such commercial pursuits. But for some projects, anything goes. On Facebook last week, a post from "Black Is magazine" posed the question: "Who's in the market for a Django Unchained action figure? Funny or offensive?"

I don't think it's particularly funny or offensive, so much as it is apropos. I'm not going to see Django. I'm not very interested in watching some black dude slaughter a bunch of white people, so much as I am interested in why that never actually happened, and what that says. I like art that begins in the disturbing truth of things and then proceeds to ask the questions which history can't.

Among those truths, for me, is the relative lack of appetite for revenge among slaves and freedmen. The great slaughter which white supremacists were always claiming to be around the corner, was never actually in the minds of slaves and freedman. What they wanted most was peace. It's true they had to kill for it. But their general perspective was "Leave me the fuck alone."

This is disturbing if you come up in a time where slavery is acknowledged by much of society as one of the great tragedies of history. There is a feeling that "They" got away with it, a sense of large injustice that haunts all of us. I am certain that my earliest attractions to the USCT had everything to do with the presence of guns, and the possibility of vengeful badassery. I found very little of that. I did find a lot of courage, a lot of humor, and a lot of pain over family divided by auction blocks. There was some talk of "Remember Ft. Pillow." But there was very little in the way of "Kill them all."

It was the same with my studies of the Underground Railroad. If you read William Still's compendium of escapes, you find very few revanchists. Instead you see an incredible number of people who escaped, not because of the labor or torture of slavery, but because a relative was sold or because they, themselves, were about to be sold to family. Slave revenge has the luxury of making slavery primarily about white people. It is a luxury that the black rebels of antebellum America had little use for. Uppermost in their minds was not ensuring that white slavers got what was coming, but the preservation and security of their particular black families. Their husbands and wives were not objects to be avenged, but actual whole people whose welfare was more important than payback I so longed to see.

It was almost as though history was refusing to give me what I wanted. And I have come to believe that right there is the thing--the tension in historical art is so much about what we want from the past and the past actually gives. All the juice lay in abandoning our assumptions, our needs, and donning the mask of a different people with different needs. This is never totally possible--but I have found the effort to be transcendent. It fills you with a feeling that is outside of yourself.

My larger point is that Django "action figures" are an excellent comment on our needs today. In that sense, they are actually like the Confederate Flag and the deification of Robert E. Lee. I don't know if this is a problem, or not. You can't really expect Americans--black or otherwise--to be American in all their other incarnations, and then suddenly change when discussing slavery. I'm pretty sure that Robert E. Lee has an action figure, too.

So this is progress. And this is democracy. It's just not for me. And I think that's alright.

Toward A More Badass History

We probably should have seen this coming:

Last fall, the National Entertainment Collectibles Association, Inc. (NECA), in tandem with the Weinstein Company, announced a full line of consumer products based on characters from the movie. First up are pose-able eight-inch action figures with tailored clothing, weaponry, and accessories in the likeness of characters played by Foxx, Kerry Washington, Samuel L. Jackson, Leonardo DiCaprio, James Remar and Christoph Waltz.

The dolls are currently on sale via Amazon.com. A press release announcing the deal stated that the line was similar to the retro toy lines that helped define the licensed action-figure market in the 1970s and that the collection will include a full apparel and accessories line. At the time of the announcement, NECA president Joel Weinshanker said the company was "very excited to bring the stellar cast of Django to life and honored to be working with another Tarantino masterpiece."

Action figures for Tarantino films Kill Bill Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 may have been better suited for such commercial pursuits. But for some projects, anything goes. On Facebook last week, a post from "Black Is magazine" posed the question: "Who's in the market for a Django Unchained action figure? Funny or offensive?"

I don't think it's particularly funny or offensive, so much as it is apropos. I'm not going to see Django. I'm not very interested in watching some black dude slaughter a bunch of white people, so much as I am interested in why that never actually happened, and what that says. I like art that begins in the disturbing truth of things and then proceeds to ask the questions which history can't.

Among those truths, for me, is the relative lack of appetite for revenge among slaves and freedmen. The great slaughter which white supremacists were always claiming to be around the corner, was never actually in the minds of slaves and freedman. What they wanted most was peace. It's true they had to kill for it. But their general perspective was "Leave me the fuck alone."

This is disturbing if you come up in a time where slavery is acknowledged by much of society as one of the great tragedies of history. There is a feeling that "They" got away with it, a sense of large injustice that haunts all of us. I am certain that my earliest attractions to the USCT had everything to do with the presence of guns, and the possibility of vengeful badassery. I found very little of that. I did find a lot of courage, a lot of humor, and a lot of pain over family divided by auction blocks. There was some talk of "Remember Ft. Pillow." But there was very little in the way of "Kill them all."

It was the same with my studies of the Underground railroad. If you read the William Still's compendium of escapes, you find very few revanchists. Instead you see an incredible number of people who escaped, not because of the labor or torture of slavery, but because a relative was sold or because they, themselves, were about to be sold to family. Slave revenge has the luxury of making slavery primarily about white people. It is a luxury that the black rebels of antebellum America had little use for. Uppermost in their minds was not ensuring that white slavers got what was coming, but the preservation and security of their particular black families. Their husbands and wives were not objects to be avenged, but actual whole people whose welfare was more important than payback I so longed to see.

It was almost as though history was refusing to give me what I wanted. And I have come to believe that right there is the thing--the tension in historical art is so much about what we want from the past and the past actually gives. All the juice lay in abandoning our assumptions, our needs, and donning the mask of a different people with different needs. This is never totally possible--but I have found the effort to be transcendent It fills you with a feeling that is outside of yourself.

My larger point is that Django "action figures" are an excellent comment on our needs today. In that sense, they are actually like the Confederate Flag and the deification of Robert E. Lee. I don't know if this is a problem, or not. You can't really expect Americans--black or otherwise--to be American in all their other incarnations, and then suddenly change when discussing slavery. I'm pretty sure that Robert E. Lee has an action figure, too.

So this is progress. And this is democracy. It's just not for me. And I think that's alright.

January 8, 2013

You Can't Fight Rape Culture With Bad Data

I think everyone should read Amanda Marcotte's piece on this graphic put out by the Enliven Project which both understates and overstates the problem. Hopefully they'll redo the graphic. But folks who are sending this around should know what they're dealing with. No point you're going to war with water pistols.

Alex Jones Pitches Government by Boxing Match

There's a telling moment in this Piers Morgan interview with Alex Jones, wherein Jones challenges Morgan to a boxing match. Jones is one of the authors of a petition to deport Piers Morgan. He also commands a fairly large talk radio audiences, and began the interview by angrily warning Morgan that any move toward gun control would open the doors to "1776."

Nevertheless, I think the fact that Jones responds to a disagreement over government policy by telling his interlocutor "well how 'bout we take this outside" is illustrative. Jones spends much of the interview ranting about the evils of government use of force, without much attention to the kind of individual violence with which he threatened Morgan. More accurately, Jones believes that the only answer to such violence is more -- presumably defensive -- violence, though his pose makes him a poor advocate for such a position.

One argument, and perhaps the greatest argument, for civil society is that we do not settle actual policy questions by asking, in Chris Rock mode, "Yes, but can you kick my ass?" That way lies the path to government by ogres, or chaos, or all against all, or all against them, or all against me. There must be a better way.

I Can Feel the Changes

I finally took some time to give a few serious spins to Kendrick Lamar's Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City. Bad on me. Really bad on me. Good Kid is not simply one the best hip-hop albums I've ever heard, but one of the most moving pieces of art I've seen/heard in a long, long, long time. I sort of initially bristled at the notion of comparison to Illmatic--my personal favorite ever--but it is exactly the right comparison. Nas was able to do was conjure the chaos of inner city black America in the late '80s and '90s. Now Kendrick Lamar summons it nearly 20 years later (with more focus, by the way) and virtually nothing has changed.

Good Kid chronicles a young 17-year old effort to visit a romantic interest, and the kind of violence that haunts such a pedestrian effort. This scenario is right out of my young Baltimore city life. I used to love The Wonder Years. But Kevin Arnold didn't have to roll five deep to go see Winnie Cooper. That was the street law when I young man, and it's depressing to hear that it still is today. But it shows how violence warps the most ordinary routine.Lamar's album is, in part, about the consequences of forgetting that law. But more than that it's also about the people who enforce it. Everyone should listen to "The Art Of Peer Pressure." It is commentary on everything from Chicago to Steubenville. Everyone should listen to "Black Boy Fly." All I can tell you is the feeling behind "Two niggas making it had never sounded logical" mirrors my own feelings as a child.

A word on "bitch." I initially felt that the album was a beautifully produced work of misogyny That mostly came from me giving a quick, inattentive listen. Good Kid deserves a lot better. It is that rare rap record that actually abandons triumphalism, invulnerability, and wears the mask. Rappers like to claim to be broadcasters, not endorsers. Except it's usually clear that they think, say, guns are pretty cool. This was that rare rap record where I thought the reflection to endorsement ratio was roughly 20 to one.

This is a great album--one that I wish had been around when I was 13. Non-rap fans should give this a listen. it is some of the best word-smithing, sentence-crafting, and beat production that hip-hop has to offer. And it is how it feels to be a black boy in the mad city. Hip-hop is obsessed with soldiers. This may be the first great record I've heard by someone obsessed with speaking as a civilian. And there have always been more of us than them.

MORE: Another quick note. Hip-hop has long been obsessed with "confessionals" and showing that gangstas have sensitive sides too. Usually this just comes off as whining. Puffy's "No Way Out" is a classic of Whine-Rap, as is almost everything Kanye West does. Rappers who whine tend to talk about Jesus a lot.

Of course not all rappers who talk about Jesus are whining. Kendrick Lamar is the MC that every other whine-rapper thinks he is. Their idea of making sensitive art is to cut a track say "HEY THIS IS ME BEING SENSITIVE. THUGS CRY TO GIRL. AND IT IS WRONG THAT I AM OBSESSED WITH WHITE WOMAN. BUT BLACK GIRLS BE BITCHEZ (DON'T JUDGE ME. JUST SAYIN.)"

Whereas Good Kid doesn't talk. It just kinda is. As great art always is.

Steubenville Justice

Michael Nodianos hasn't been charged with a crime in connection to the alleged rape of a 16-year-old girl by two members of the Steubenville High School football team in August. The case ignited a firestorm of controversy and national attention after hackers affiliated with the group Anonymous began breaking into the websites and email accounts of several football players and locals. The hackers believed these people had gotten off too lightly.

Nodianos' departure from OSU is the result of Anonymous' hacking campaign. Amanda Marcotte takes on the ethics of all of this:

As some initial gleeful Twitter responses from students to the alleged rape demonstrate, one reason rape continues is that communities not only don't hold perpetrators responsible, but close ranks to defend or even celebrate them. By stepping in and holding people accountable, Anonymous stands a very good chance of taking action that actually does something to stop rape.

But: This type of online vigilante justice is potentially invading the privacy of or defaming innocent Steubenville residents, and even if everything published is true, there are very serious legal limits to the Anonymous strategy. Not all of the leaked allegations are attached to Twitter or YouTube accounts--many of the most serious cover-up claims, which we won't reprint here, are at this point only rumor. The allegations will infuriate you, but they don't rise to the level of real evidence that can be used to truly hold responsible those who participate in sex crimes.

Nodianos and his family have all faced threats and people attempting to find out his class schedule. I think that's wrong. Nodianos should have the right to go about his life, free of violence -- both threatened and actual -- no matter what he said on any tape.

At the same time, I also think that violent crime is not just an offense against any victims, but an offense against society. If your response to a brutal crime perpetrated against a defenseless victim is to cut a video in which you laugh your head off, you should expect society to take offense and subject you to some amount of inconvenience.

A the core of all of this is the really poor job we do in terms of prosecuting rape. I have little in the way of ideas as to how to get better. But if there is support for Anonymous's tactics -- which I think are as spectacular as they are dangerous -- it comes out of an utter frustration with how we handle (or don't handle) sexual violence.

January 4, 2013

The Hollywood America Deserves

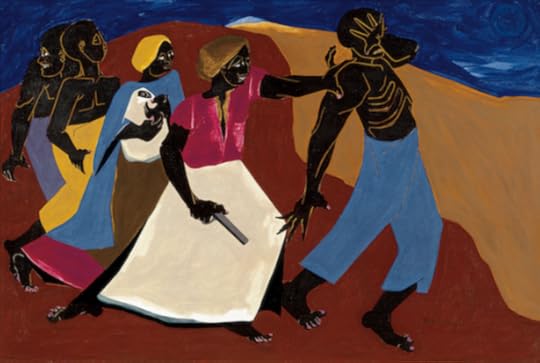

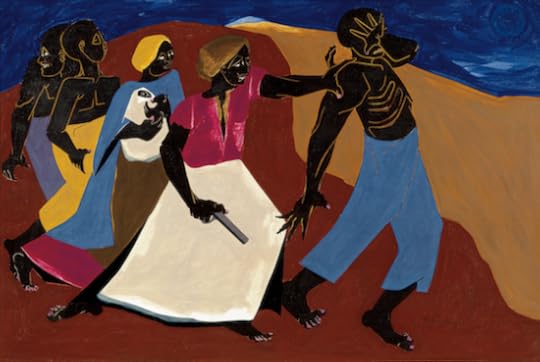

A painting by Jacob Lawrence from his Harriet Tubman series.

A painting by Jacob Lawrence from his Harriet Tubman series.One of the rather frequent responses I get when posting the stories of people like Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, or Robert Smalls is that their story deserves to be a movie. A biopic is seen by a lot of us as the ultimate testimonial to a person's life. Moreover, movies have the unique power to reach and influence millions of people. Finally, movies offer the possibility of all the imagery and input we hold when thinking of, say, Harriet Tubman to be made manifest before the world. I think this impulse is basically correct. It is especially correct given that Hollywood doesn't just ignore slavery and the Civil War but turns out revisionist dreck like Gods and Generals.

At the same time I think it's important to not talk as though it were an entity separate from the politics, economics, and history of America. The person who would bankroll a Harriet Tubman biopic would likely be someone who was particularly touched by her story. Such a person would not have to be black, but I don't know how you separate the paucity of black people with the power to green-light from the paucity of good films concerning black people in American history.

Moreover, movie-making is risky and expensive. Any discussion of the lack of a Harriet Tubman biopic should begin with the shameful fact that median white wealth in this country stands at $110,000 and median black wealth stands at around $5,000. It would be nice to think that this gap reflected choices cultural and otherwise, instead of the fact that for most this country's history its governing policy was to produce failure in black communities, and most of its citizens supported such policies. It would be nice if Hollywood were more moral and forward-thinking than its consumer base. But I would not wait around for such a day.

What I would do is interrogate the basic premise that holds that black lives (or any heroic life) is not truly legend unless a financier decides it should be. Movies are an art form—one that I very much enjoy—but they are one of many. Those of us who are unhappy with Hollywood's presentation of black life should not restrict themselves to Hollywood. What was the last play we saw by a black writer? What was the last book by a black writer we read? What did we give for Christmas, Kwanzaa or Hanukkah? When was the last time we went to see an exhibit by a black artist?

Finally, this is a particular moment in Hollywood—one wherein glorious righteous violence and what Alyssa Rosenberg calls "transgressive badassery" reigns supreme. I do wish Hollywood would do other kinds of movies. But a constant view of slavery through lens of badassery somehow feels like more of the same.

January 3, 2013

The Myth of Harriet Tubman

Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Lawrence I recently finished Kate Larsen's excellent biography of Harriet Tubman--Bound For The Promised Land. Tubman, like any mythical figure has had her exploits elevated beyond actual events. But even in Larsen's historical telling she emerges as a super-heroic figure. It's true she didn't shepherd 200 slaves out of Maryland. The number was more like 70--which is to say, given the logistics, a lot.

At any rate, I've done a lot of thinking on the place of myth in African-American history. Django aside, we don't really have many avenging angels. Reviewing the primary documents of the time, I don't even detect much taste for mass vengeance. There's often a taste for particular vengeance on particular people, but more than anything there's a strong desire to be left the fuck alone. Actions, like absconding with oneself, are usually set in motion by the threat of sale and the disruption of family ties. At first I was surprised by the lack of race hatred. But when I thought about it, it makes sense.Race hatred among whites was not irrational devolution. On the contrary it served an actual political purpose--defining the borders of citizenship, manhood and the broadest aristocracy ever created. Race hatred among blacks is just vengeance. It doesn't really go anywhere. It doesn't offer access to anything you didn't have before. Even if you look at the actual ideology of black nationalists what you will find more than "Kill Whitey" is "Leave us the fuck alone." Whereas integrationists wanted to be left alone here as Americans, separatists wanted to be left alone elsewhere. But both wanted to left alone.

That said, the black freedom movement isn't faultlessly benign. Above is painting from Jacob Lawrence's awesome series on Harriet Tubman. It takes as inspiration Tubman's famous aphorism--"Dead niggers tell no tales." (Yes that's Harriet Tubman, not DMX.) Tubman was known, on at least one occasion, to force an escaped slave forward at gun-point. The point was practical--should the slave return he would be tortured, and give up Tubman's methods. What I love most about this piece is how the man is shielding his face from the freedom that lay before him, or perhaps mourning the friends, and possibly family, he's left behind.

Freedom must have been scary for these peoples. Tubman says when she first escaped, she felt like a man who'd been let out jail after long bid. There was no one there to greet her. No home to return to. She had to make her way alone. And she did--along with a lot of others.

The Myth Of Harriet Tubman

I recently finished Kate Larsen's excellent biography of Harriet Tubman--Bound For The Promised Land. Tubman, like any mythical figure has had her exploits elevated beyond actual events. But even in Larsen's historical telling she emerges as a super-heroic figure. It's true she didn't shepherd 200 slaves out of Maryland. The number was more like 70--which to say, given the logistics, a lot.

At any rate, I've done a lot of thinking on the place of myth in African-American history. Django aside, we don't really have many avenging angels. Reviewing the primary documents of the time, I don't even detect much taste for mass vengeance. There's often a taste for particular vengeance on particular people, but more than anything there's a strong desire to be left the fuck alone. Actions, like absconding with oneself, are usually set in motion by the threat of sale and the disruption of family ties. At first I was surprised by the lack of race hatred. But when I thought about it, it makes sense.

Race hatred among whites was not irrational devolution. On the contrary it served an actual political purpose--defining the borders of citizenship, manhood and the broadest aristocracy ever created. Race hatred among blacks is just vengeance. It doesn't really go anywhere. It doesn't offer access to anything you didn't have before. Even if you look at the actual ideology of black nationalists what you will find more than "Kill Whitey" is "Leave us the fuck alone." Whereas integrationists wanted to be left alone here as Americans, separatists wanted to be left alone elsewhere. But both wanted to left alone.

That said, the black freedom movement isn't faultlessly benign. Above is painting from Jacob Lawrence's awesome series on Harriet Tubman. It takes as inspiration Tubman's famous aphorism--"Dead niggers tell no tales." (Yes that's Harriet Tubman, not DMX.) Tubman was known, on at least one occasion, to force an escaped slave forward at gun-point. The point was practical--should the slave return he would be tortured, and give up Tubman's methods. What I love most about this piece is how the man is shielding his face from the freedom that lay before him, or perhaps mourning the friends, and possibly family, he's left behind,

Freedom must have been scary for these peoples. Tubman says when she first escaped, she felt like a man who'd been let out jail after long bid. There was no one there to greet her. No home to return to. She had to make her way alone. And she did--along with a lot of others.

It's Not You, It's Me

But now there's the matter of time. I basically have two governing passions in my life--writing and family--and everything, somehow, ties to one of them. And the older I've gotten the more time each has taken from me. (And the more they have given back.) When I was 25 there just seemed like there was so much time. And then there's the fact that both of my passions are so tied to brain function. I don't know what I am without my writing and my family. And I don't what those things would be to me with an (more) inhibited brain.

I thought about that constantly last season. It probably goes to far to say I watched football strictly for the violence. But I certainly didn't watch in spite of it. I can't say I would have felt the same about flag football. When Ray Lewis would smash into Eddie George, I would feel an electric charge surge through me. And I loved it. I loved Ronnie Lott because he was such a big hitter. I still think fondly of Steve Atwater--like the recovering alcoholic recalling one of his great benders. But the fact of the matter is that my view of violence--ritual and otherwise--has changed in the past ten years. I hear Ray Lewis is retiring. And all I can do is worry about his brain.

Which isn't to say that I didn't miss some things. I'm mostly sad I missed the quarterback play of RGIII and Andrew Luck. I'm really sorry I missed Peyton Manning's comeback. I watched a half of one game this year--the Thanksgiving day game, so I did get to see some of RGIII's wizardry. And on that note, I caught enough news to be very happy to no longer be a Cowboys fan. On Sunday, my twitter stream was filled with people laughing at Tony Romo and Jerry Jones. It was like hearing that your lush of an ex-spouse had, yet again, made of a drunken fool of himself at the company party. You are sort of embarrassed for him. But you are also glad to no longer be attached. He'll never change.

Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog

- Ta-Nehisi Coates's profile

- 16959 followers