Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog, page 61

February 19, 2013

Morning Coffee

Speaking of which, I need to say that Stephanie Mills holds the crown--mashing Diana Ross, and sonning, even, the goddess Whitney. I missed this because when Mill's version was released I was in my "hardcore, no R&B singer" phase. My loss. Mills just kills it at the end, though she could do without the backup. She don't need it. I tell you, I'm playing this one a lot this morning.

February 18, 2013

Hobbes, Aristotle, and the Senses

Fortunately Jonathan explained it for us:

Aristotle, like Hobbes, did think that knowledge came from the senses, but he had a very different view of how senses worked. Aristotle believed that every physical object has a form or essence, and a substance. So a clay model of a tree and real tree share commonalities of form, although their substances are totally different. Aristotle also thought that the psyche is an instrument whereby we can receive the form of objects without the substance. He compares sensation to a signet ring making an impression of wax.

Hobbes, however, does not really believe that the concept of "essence" is useful in explaining the world. He is basically a materialist. He believes that the only things worth talking about are matter and its interactions. Therefore, his account of how we obtain knowledge through the senses has to rely on interaction between matter.

This might sound like an obscure difference, but it has a lot of consequences for how one studies the world. If you agree with Aristotle, the implication is that by observing the world, you can get an idea of the real essence of things. Acquiring theoretical knowledge is then a matter of thinking rationally about the implications of this knowledge. Thus physical science is a matter of everyday observation followed by rigorous thinking.

However, if the information you get from the senses is just a bunch of particles bouncing off of your sensory organs, as Hobbes believes, then there's good reason to be worried that the senses are unreliable, and you need to spend time carefully tweaking the information you get from the senses to make sure you have it right. This gives rise to an experimental model (which Hobbes' contemporary, Francis Bacon, focused on far more than Hobbes did).

As for how commonplace it was - Aristotelianism was basically the dominant philosophy from the time of Thomas Aquinas (1200s) up until the 1600s. Hobbes is writing around the time of transition away from Aristotle's position as the preeminent thinker on matters such as this. I actually am not sure how dominant the view still was among academics by the time of the Leviathan.

As an aside, the reason Hobbes talks about mediate and immediate interaction is that, at the time, people who subscribed to this materialst view did not believe that matter could interact with other matter at a distance. The only interactions allowed into the theory were direct ones. The view of no interaction at a distance was thrown out after Newton's theory of gravity became the consensus view - since gravity is interaction at a distance.

Hilzoy also stepped in to help us understand the difference:

A few notes: first, when Hobbes talks about the scholastic view of knowledge, ("they say the thing understood sendeth forth an intelligible species", etc.), this is not similar to the way we now understand smell. Scholastics, following Aristotle, thought that objects were composed of matter and form. I.e., a computer is a bunch of metal and plastic and silicon and stuff (the matter), arranged in a particular way (the form). If you had exactly the same matter, but it was a bunch of molten metal and a pile of sand, it would not be the same object; likewise, if you had an identical computer made of different bits of metal and silicon and whatever. 'Species' is scholastic-speak for 'form'; the objects are (according to the scholastics) giving off forms of themselves, whereas (as I understand it) we now think that objects we smell give off matter.

Second: I don't recall how significant this is in the rest of Hobbes' work, but the claim that ALL thoughts concern "a representation or appearance of some quality, or other accident of a body without us, which is commonly called an object" is significant, and probably false. Can we think about abstract objects, nonexistent objects, logical arguments, etc.? Are all these "objects without us"? You could argue, as Hume did, that all our thoughts are either about objects of internal or external sense, but can be cut and pasted to create e.g. nonexistent objects. But is it obvious at all that thinking about (for instance) logical validity is in any sense thinking about an object outside us, or is the product of cutting and pasting concepts originally derived from such thoughts? Not to me.

I started this project trying to understand "social contract." I guess we'll get to that eventually, but all the knowledge I'm picking up on the way is awesome. In education we tend to be goal-oriented, and goals are important. But at the same time we forget that part of the beauty of learning lay in all the bits you acquire, almost accidentally, along the way. I think those bits are the stuff of wisdom, as opposed to just "facts."

If I can write you an essay on the history of "social contract" at the end of all this, that's cool. But it would be much better if I could--in some deep way--tell you something about the world of Hobbes, the world of Locke, the world of Rosseau, and what each of those particular worlds means for our own world today. It's one of the reasons why I push us to do something more than study history as a way of refuting our racist uncle at Thanksgiving, or serving the homophobe from high school who keeps popping up on our Facebook feed.

If you spend your day debating whether the earth is flat or not, how do you ever get to the truly profound questions of cosmology? It's not within your power to banish ignorance from the world, or even from Facebook. Besides, you have your own ignorance to bear.

Hobbes, Aristotle And The Senses

Fortunately Jonathan explained it for us:

Aristotle, like Hobbes, did think that knowledge came from the senses, but he had a very different view of how senses worked. Aristotle believed that every physical object has a form or essence, and a substance. So a clay model of a tree and real tree share commonalities of form, although their substances are totally different. Aristotle also thought that the psyche is an instrument whereby we can receive the form of objects without the substance. He compares sensation to a signet ring making an impression of wax.

Hobbes, however, does not really believe that the concept of "essence" is useful in explaining the world. He is basically a materialist. He believes that the only things worth talking about are matter and its interactions. Therefore, his account of how we obtain knowledge through the senses has to rely on interaction between matter.

This might sound like an obscure difference, but it has a lot of consequences for how one studies the world. If you agree with Aristotle, the implication is that by observing the world, you can get an idea of the real essence of things. Acquiring theoretical knowledge is then a matter of thinking rationally about the implications of this knowledge. Thus physical science is a matter of everyday observation followed by rigorous thinking.

However, if the information you get from the senses is just a bunch of particles bouncing off of your sensory organs, as Hobbes believes, then there's good reason to be worried that the senses are unreliable, and you need to spend time carefully tweaking the information you get from the senses to make sure you have it right. This gives rise to an experimental model (which Hobbes' contemporary, Francis Bacon, focused on far more than Hobbes did).

As for how commonplace it was - Aristotelianism was basically the dominant philosophy from the time of Thomas Aquinas (1200s) up until the 1600s. Hobbes is writing around the time of transition away from Aristotle's position as the preeminent thinker on matters such as this. I actually am not sure how dominant the view still was among academics by the time of the Leviathan.

As an aside, the reason Hobbes talks about mediate and immediate interaction is that, at the time, people who subscribed to this materialst view did not believe that matter could interact with other matter at a distance. The only interactions allowed into the theory were direct ones. The view of no interaction at a distance was thrown out after Newton's theory of gravity became the consensus view - since gravity is interaction at a distance.

Hilzoy also stepped in to help us understand the difference:

A few notes: first, when Hobbes talks about the scholastic view of knowledge, ("they say the thing understood sendeth forth an intelligible species", etc.), this is not similar to the way we now understand smell. Scholastics, following Aristotle, thought that objects were composed of matter and form. I.e., a computer is a bunch of metal and plastic and silicon and stuff (the matter), arranged in a particular way (the form). If you had exactly the same matter, but it was a bunch of molten metal and a pile of sand, it would not be the same object; likewise, if you had an identical computer made of different bits of metal and silicon and whatever. 'Species' is scholastic-speak for 'form'; the objects are (according to the scholastics) giving off forms of themselves, whereas (as I understand it) we now think that objects we smell give off matter.

Second: I don't recall how significant this is in the rest of Hobbes' work, but the claim that ALL thoughts concern "a representation or appearance of some quality, or other accident of a body without us, which is commonly called an object" is significant, and probably false. Can we think about abstract objects, nonexistent objects, logical arguments, etc.? Are all these "objects without us"? You could argue, as Hume did, that all our thoughts are either about objects of internal or external sense, but can be cut and pasted to create e.g. nonexistent objects. But is it obvious at all that thinking about (for instance) logical validity is in any sense thinking about an object outside us, or is the product of cutting and pasting concepts originally derived from such thoughts? Not to me.

I started this project trying to understand "social contract." I guess we'll get to that eventually, but all the knowledge I'm picking up on the way is awesome. In education we tend to be goal-oriented, and goals are important. But at the same time we forget that part of the beauty of learning lay in all the bits you acquire, almost accidentally, along the way. I think those bits are the stuff of wisdom, as opposed to just "facts."

If I can write you an essay on the history of "social contract" at the end of all this, that's cool. But it would be much better if I could--in some deep way--tell you something about the world of Hobbes, the world of Locke, the world of Rosseau, and what each of those particular worlds means for our own world today. It's one of the reasons why I push us to do something more than study history as a way of refuting our racist uncle at Thanksgiving, or serving the homophobe from high school who keeps popping up on our Facebook feed.

If you spend your day debating whether the earth is flat or not, how do you ever get to the truly profound questions of cosmology? It's not within your power to banish ignorance from the world, or even from Facebook. Besides, you have your own ignorance to bear.

February 15, 2013

The Art of Infinite War, Ctd.: The Administration's Drone Campaign

Before getting into the issues you raise, I think it's important to look at the broader context, which sees the convergence of two long-term historical trends and one more-recent one. To simplify, these are:

1. The collapse of a regional order in Islamic North and Sahelian Africa that dates back to the beginning of the post-colonial period. That order was based on support for repressive authoritarian regimes in return for stability. During the Cold War, stability was defined as anti-communist. In the late- and post-Cold War period, stability was defined as anti-Islamist (in the sense of political Islam). With the Arab Spring, and for other reasons in the Sahel, this exchange has become inacceptable. The new regional order is uncertain, unstable and has left everyone unprepared in terms of how to approach it strategically.

2. This collapse is taking place against the backdrop of an upsurge of fundamentalist Islam, with a small but very determined minority willing to use violence to achieve their vision of a "pure" Islamic state. This upsurge predated the collapse, but is now complicating it. Many of these movements are locally based with local objectives and varying degrees of religious extremism. (The Tuaregs in northern Mali, for instance, are divided between secular nationalists and Islamic jihadists.) However, there is again a small but motivated, highly mobile, well-financed and globalized cadre of jihadists able and willing to graft themselves onto regional movements that seem poised to achieve tactical success. This upsurge is just the latest iteration of a cyclical and at times violent ebb-and-flow tug-of-war between moderate Islam (usually trading cultures) and fundamentalist Islam that dates back to soon after Islam's spread to Northern and Sahelian Africa.

3. Both of these long-term trends are now converging with a more recent one, which can be thought of as a tactical/strategic stalemate between technologically advanced militaries (the U.S. and its European allies) and asymmetric local insurgencies and globalized terrorist networks. The initial military phase of the French intervention in Mali demonstrates that although insurgents armed with heavy arms and pick-up trucks can overwhelm the poorly trained and poorly equipped armies of their national governments, they do not stand a chance against a well-coordinated, combined arms campaign waged by even a small Western military contingent. But we also know from Afghanistan and Iraq that this is not enough to ensure "victory," defined as the achievement of our strategic objectives (a stable state, preferably democratic and aligned with the U.S., but at the least one that is compliant with global norms of state behavior). From there, many people make the mistake of concluding that the insurgents are destined to "win." This is misleading, though, because the conflicts of the past decade have demonstrated that neither side can achieve anything more than local tactical victories, defined as control of territory through presence, and wherever insurgents have achieved such local victories (the Pakistani tribal areas, areas of Yemen and Iraq), they have almost immediately turned the local population against them due to their implementation of a strict and brutal Islamic law that very few actually subscribe to. The result is that both sides are fighting a conflict that neither can win, in a strategic sense, without a willingness to commit endlessly to the application of violence.

Now we get to Obama, drones and the question of infinite war. For budgetary and political reasons, the U.S. can no longer commit to the kind of long-term state-building counterinsurgency campaigns we saw in Iraq and Afghanistan everywhere the threat of destabilization currently exists. It's important to add that, historically, these campaigns have been far from conclusively successful. Either way, until the advent of armed drone technology, abandoning boot-heavy counterinsurgency campaigns usually meant abandoning the fight altogether.

In this context, Obama's shift to drone and special operations strikes represents a trade-off: We know we can't win with boots on the ground, but at least this way, we will prevent the other side from winning, at a cost in money and (American) blood that we're willing to accept. The approach has long been known among the Israeli military (with regard to Hamas in Gaza) as "mowing the grass," and that term is now being used by the U.S. military as well. It acknowledges not only that such strikes will be inconclusive, but that it will be necessary to repeat them periodically.

You, like many critics of this approach, are now raising the moral cost it exacts. That is a valid and necessary effort, especially with regard to the lack of transparency and oversight in the process of target selection and the use of methods such as signature strikes, which, absent hard evidence of either the presence of a high-value individual target or knowledge of the location as a known gathering place of "bad guys," is arguably a war crime and perhaps a crime against humanity of the kind we are currently accusing Syrian President Bashar al-Assad of engaging in. Other critics question the tactical and especially the strategic effectiveness of drone strikes, while others worry about the precedent we are setting for other nations when they catch up to us in their drone capabilities. (Micah Zenko of the CFR is doing yeoman's work on this topic, by the way, in case you are not familiar with his work.)

I would just suggest that in weighing that balance, the choice is not between "infinite war" and "peace," but between "infinite war" and "persistent violence." Should the U.S. disengage from this fight, that violence will be directed by our current enemies toward the populations of the areas in question, but it will have indirect costs to regional stability, integration into global trade and supply chains (which, while not a panacea, do have an impact on local well-being), and humanitarian aid efforts. All of that is in addition to the potential threat of terrorist attacks against U.S. citizens and perhaps even the homeland. The final point I'd add is that the U.S. is the only nation on earth capable of conducting such a campaign, and if we do discontinue it, for all the valid and compelling reasons you and others have been developing, no one else will step in to contain these movements. That, too, needs to be considered.

The Art Of Infinite War Ctd.

Before getting into the issues you raise, I think it's important to look at the broader context, which sees the convergence of two long-term historical trends and one more-recent one. To simplify, these are:

1. The collapse of a regional order in Islamic North and Sahelian Africa that dates back to the beginning of the post-colonial period. That order was based on support for repressive authoritarian regimes in return for stability. During the Cold War, stability was defined as anti-communist. In the late- and post-Cold War period, stability was defined as anti-Islamist (in the sense of political Islam). With the Arab Spring, and for other reasons in the Sahel, this exchange has become inacceptable. The new regional order is uncertain, unstable and has left everyone unprepared in terms of how to approach it strategically.

2. This collapse is taking place against the backdrop of an upsurge of fundamentalist Islam, with a small but very determined minority willing to use violence to achieve their vision of a "pure" Islamic state. This upsurge predated the collapse, but is now complicating it. Many of these movements are locally based with local objectives and varying degrees of religious extremism. (The Tuaregs in northern Mali, for instance, are divided between secular nationalists and Islamic jihadists.) However, there is again a small but motivated, highly mobile, well-financed and globalized cadre of jihadists able and willing to graft themselves onto regional movements that seem poised to achieve tactical success. This upsurge is just the latest iteration of a cyclical and at times violent ebb-and-flow tug-of-war between moderate Islam (usually trading cultures) and fundamentalist Islam that dates back to soon after Islam's spread to Northern and Sahelian Africa.

3. Both of these long-term trends are now converging with a more recent one, which can be thought of as a tactical/strategic stalemate between technologically advanced militaries (the U.S. and its European allies) and asymmetric local insurgencies and globalized terrorist networks. The initial military phase of the French intervention in Mali demonstrates that although insurgents armed with heavy arms and pick-up trucks can overwhelm the poorly trained and poorly equipped armies of their national governments, they do not stand a chance against a well-coordinated, combined arms campaign waged by even a small Western military contingent. But we also know from Afghanistan and Iraq that this is not enough to ensure "victory," defined as the achievement of our strategic objectives (a stable state, preferably democratic and aligned with the U.S., but at the least one that is compliant with global norms of state behavior). From there, many people make the mistake of concluding that the insurgents are destined to "win." This is misleading, though, because the conflicts of the past decade have demonstrated that neither side can achieve anything more than local tactical victories, defined as control of territory through presence, and wherever insurgents have achieved such local victories (the Pakistani tribal areas, areas of Yemen and Iraq), they have almost immediately turned the local population against them due to their implementation of a strict and brutal Islamic law that very few actually subscribe to. The result is that both sides are fighting a conflict that neither can win, in a strategic sense, without a willingness to commit endlessly to the application of violence.

Now we get to Obama, drones and the question of infinite war. For budgetary and political reasons, the U.S. can no longer commit to the kind of long-term state-building counterinsurgency campaigns we saw in Iraq and Afghanistan everywhere the threat of destabilization currently exists. It's important to add that, historically, these campaigns have been far from conclusively successful. Either way, until the advent of armed drone technology, abandoning boot-heavy counterinsurgency campaigns usually meant abandoning the fight altogether.

In this context, Obama's shift to drone and special operations strikes represents a trade-off: We know we can't win with boots on the ground, but at least this way, we will prevent the other side from winning, at a cost in money and (American) blood that we're willing to accept. The approach has long been known among the Israeli military (with regard to Hamas in Gaza) as "mowing the grass," and that term is now being used by the U.S. military as well. It acknowledges not only that such strikes will be inconclusive, but that it will be necessary to repeat them periodically.

You, like many critics of this approach, are now raising the moral cost it exacts. That is a valid and necessary effort, especially with regard to the lack of transparency and oversight in the process of target selection and the use of methods such as signature strikes, which, absent hard evidence of either the presence of a high-value individual target or knowledge of the location as a known gathering place of "bad guys," is arguably a war crime and perhaps a crime against humanity of the kind we are currently accusing Syrian President Bashar al-Assad of engaging in. Other critics question the tactical and especially the strategic effectiveness of drone strikes, while others worry about the precedent we are setting for other nations when they catch up to us in their drone capabilities. (Micah Zenko of the CFR is doing yeoman's work on this topic, by the way, in case you are not familiar with his work.)

I would just suggest that in weighing that balance, the choice is not between "infinite war" and "peace," but between "infinite war" and "persistent violence." Should the U.S. disengage from this fight, that violence will be directed by our current enemies toward the populations of the areas in question, but it will have indirect costs to regional stability, integration into global trade and supply chains (which, while not a panacea, do have an impact on local well-being), and humanitarian aid efforts. All of that is in addition to the potential threat of terrorist attacks against U.S. citizens and perhaps even the homeland. The final point I'd add is that the U.S. is the only nation on earth capable of conducting such a campaign, and if we do discontinue it, for all the valid and compelling reasons you and others have been developing, no one else will step in to contain these movements. That, too, needs to be considered.

Western Thought for College Dropouts and Lonesome Socialists

Leviathan (Chapter I: Sense)

It's easy to forget that Leviathan isn't just an important text in the world of Western philosophy, but that's it's also a kind of primary historical source. So what struck me most about this chapter was what appears to be a debate about neuro-biology and human anatomy between Hobbes and his contemporaries.

Hobbes defines sense as result of pressure put upon the sense-organ. So your spouse applies light pressure to your shoulders, and you experience this as a gentle massage. My father makes waffles in the kitchen and I experience this (initially) as a pleasant odor wafting out through the house. A terror suspect is water-boarded and experiences severe pain. Light from a canvas strikes my eyes, and I experience the various colors in a painting. What seems important to Hobbes is the space between the thing itself (which is outside of me, or "without") and my sense of thing (which is inside of me or "within.")

Hobbes writes:

And though at some certain distance the real and very object seem invested with the fancy it begets in us; yet still the object is one thing, the image or fancy is another. So that sense in all cases is nothing else but original fancy caused (as I have said) by the pressure that is, by the motion of external things upon our eyes, ears, and other organs, thereunto ordained

We may all say that the sky is blue. But in fact the sky is just...they sky. The blue is in us.

Hobbes seems himself in competition with prevailing world-view of philosophers. They believe, for instance, that the waffles my father prepares in the kitchen are not merely sitting in the kitchen pressuring my olfactory nerves, but that they've sent some portion of themselves--some "show, apparition or aspect"--which my sensory organ than receives. I am not up on my sciences, but I think this is sort of how smell works. Perhaps Hobbes would say that while molecules from the waffles are conveyed and put pressure upon my nerves, the waffles themselves are still in the kitchen.

I think this is important:

Nay, for the cause of understanding also, they say the thing understood sendeth forth an intelligible species, that is, an intelligible being seen; which, coming into the understanding, makes us understand. I say not this, as disapproving the use of universities: but because I am to speak hereafter of their office in a Commonwealth, I must let you see on all occasions by the way what things would be amended in them; amongst which the frequency of insignificant speech is one.

So Hobbes sees his opposition not speaking of pieces, but almost of independent wholes. In the case of an idea, an intelligent being (a spirit? a ghost?) is conveyed forward to us thus gifting "understanding." Of course for college dropout the shots Hobbes fires (repeatedly, by the way) at the universities and their "frequency of insignificant speech" thrill me.

Was this text incendiary at the time? Was it heretical? How far was Hobbes removed from his contemporaries? How radical was the break? And this notion of all the sciences and arts as interconnected, when did that leave us? Are we still encouraged to think in that broad manner? Have we lost something in our education by not drawing lines from biology to philosophy?

I have written this without resorting to wikipedia or the internet or anything but the text itself. I don't want to project an "aspect" of wisdom. I expect to garner plenty of wisdom from you.

See last week's post here.

Western Thought For College Dropouts And Lonesome Socialists

Leviathan (Chapter I: Sense)

It's easy to forget that Leviathan isn't just an important text in the world of Western philosophy, but that's it's also a kind of primary historical source. So what struck me most about this chapter was what appears to be a debate about neuro-biology and human anatomy between Hobbes and his contemporaries.

Hobbes defines sense as result of pressure put upon the sense-organ. So your spouse applies light pressure to your shoulders, and you experience this as a gentle massage. My father makes waffles in the kitchen and I experience this (initially) as a pleasant odor wafting out through the house. A terror suspect is water-boarded and experiences severe pain. Light from a canvas strikes my eyes, and I experience the various colors in a painting. What seems important to Hobbes is the space between the thing itself (which is outside of me, or "without") and my sense of thing (which is inside of me or "within.")

Hobbes writes:

And though at some certain distance the real and very object seem invested with the fancy it begets in us; yet still the object is one thing, the image or fancy is another. So that sense in all cases is nothing else but original fancy caused (as I have said) by the pressure that is, by the motion of external things upon our eyes, ears, and other organs, thereunto ordained

We may all say that the sky is blue. But in fact the sky is just...they sky. The blue is in us.

Hobbes seems himself in competition with prevailing world-view of philosophers. They believe, for instance, that the waffles my father prepares in the kitchen are not merely sitting in the kitchen pressuring my olfactory nerves, but that they've sent some portion of themselves--some "show, apparition or aspect"--which my sensory organ than receives. I am not up on my sciences, but I think this is sort of how smell works. Perhaps Hobbes would say that while molecules from the waffles are conveyed and put pressure upon my nerves, the waffles themselves are still in the kitchen.

I think this is important:

Nay, for the cause of understanding also, they say the thing understood sendeth forth an intelligible species, that is, an intelligible being seen; which, coming into the understanding, makes us understand. I say not this, as disapproving the use of universities: but because I am to speak hereafter of their office in a Commonwealth, I must let you see on all occasions by the way what things would be amended in them; amongst which the frequency of insignificant speech is one.

So Hobbes sees his opposition saying not speaking of pieces, but almost of independent wholes. In the case of an idea, an intelligent being (a spirit? a ghost?) is conveyed forward to us thus gifting "understanding." Of course for college dropout the shots Hobbes fires (repeatedly, by the way) at the universities and their "frequency of insignificant speech" thrill me.

Was this text incendiary at the time? Was it heretical? How far was Hobbes removed from his contemporaries? How radical was the break? And this notion of all the sciences and arts as interconnected, when did that leave us? Are we still encouraged to think in that broad manner? Have we lost something in our education by not drawing lines from biology to philosophy?

I have written this without resorting to wikipedia or the internet or anything but the text itself. I don't want to project an "aspect" of wisdom. I expect to garner plenty of wisdom from you.

See last week's post here.

February 14, 2013

The Lost Battalion

The Social Trends Driving American Gangs and Gun Violence

Learning from University of Chicago Crime Lab's Harold Pollack, a man who helped make the misuse of firearms a public health issue

Outside the funeral for Hadiya Pendleton, the Obama inauguration performer killed by a gunman in a Chicago park on January 29 (John Gress/Reuters)

Outside the funeral for Hadiya Pendleton, the Obama inauguration performer killed by a gunman in a Chicago park on January 29 (John Gress/Reuters) Like everyone, we at The Atlantic have spent the weeks since Newtown thinking about the role of guns in America. In our ongoing effort to broaden the conversation, I spent some time talking to Professor Harold Pollack, who co-directs the Crime Lab at the University of Chicago. Pollack is one of the foremost voices on gun violence from a public health perspective. Pollack and his colleagues at the Crime Lab have done yeoman's work in helping us understand how guns end up on the streets of cities like Chicago, and how precisely they tend to be used.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Hi, Harold. Thanks so much for taking the time to join us over here at The Atlantic. We've had several off-line conversations which have been illuminating to me. I greatly appreciate your willingness to take some time to do this for the Horde, as we say on the blog.

Harold Pollack: It's great to correspond with you, Ta-Nehisi, regarding what can actually be done to reduce gun violence. I'm a big fan of your work. I should mention by way of self-introduction that I am a public health researcher at the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration and co-director of the University of Chicago Crime Lab.

Here in Chicago, we have become the focus of much national attention because we had our 500th homicide [of the year in 2012]. We're sometimes called the nation's murder capital -- though this mainly reflects the fact that we are a big city. We're more dangerous than L.A. or New York, but we're actually in the middle of the pack when it comes to homicide rates. Still, we're dangerous enough. The declining homicide rates in many prosperous and middle-class neighborhoods casts a harsh light on the high rates facing African-American (and to a lesser-extent) Latino young men on the city's south and west sides. Lots to talk about. I am looking forward to talking. So let's get to it.

I don't know if I've told you how I come to this issue, but I should say for everyone reading this that I am from Baltimore -- the West Side, as we used to call it. I came of age in the late 1980s and early 90s, a period in which violence spiked in our cities. I don't know if Chicago today is as bad as it was in, say, 1988, but this was a period of deep fear for everyone in the black communities of Baltimore. And the fear was everywhere.

It changed how we addressed our parents. It changed how we addressed each other. It changed our music. The violence put rules in place that often look strange to the rest of the country. For instance, the mask of hyper-machismo and invulnerability -- the ice-grill, as we used to say -- looks strange, until you've lived in a place where that mask is the only power you have to effect a modicum of safety.

I'm in my late 40s. I was a typical suburban kid graduating high school outside New York. It wasn't as tough for me as it was on the west side of Baltimore, but crime certainly touched my life. On one occasion, I was in Washington Heights on my way to an AP class at Columbia University. A group of middle-school or early-high-school kids jumped me in the subway station, and they attempted to wrest away my watch. My high school sweetheart had just given it to me; I didn't want to give it up. So a kid grabbed me by the hair and smashed my head against the concrete floor until I finally relented. As you know, my cousin was beaten to death by two teenage house burglars a few years later.

So I remember very well both the fear and the anger that accompanies one's sense of physical vulnerability. Of course this anger often comes with a race/ethnic/class tinge that poisons so much of what we are trying to do in revitalizing urban America.

It's odd. I sometimes travel in some pretty tough neighborhoods, and it's been maybe 20 years since someone has laid an unfriendly hand on me. The gray hair seems to put me in a different category. The kids we encounter are sometimes a bit struck that one can be a shrimpy, nerdy guy and be a successful adult man. That option doesn't seem as open to them.

I remember when Allen Iverson came into the NBA and people could not understand why he walked around with twenty dudes. I totally understood, and I suspect a lot of black males did too. But one thing that's become clear to me, and that I've tried to grapple with in my blogging, is that cultural practices that offer some protection in one place are often quite harmful in another. Iverson's clique may have saved him countless times in Virginia Beach. But in that broader world, they sometimes empowered his worst urges. So much of my work is about how young black males negotiate violence, and how those negotiations affect them when they interact with the broader world.

I get a sense of that when I talk with young men in Chicago who participate in violence prevention efforts. Kids are wearing that ice-grill for some very real reasons in their world. It's just a tough assignment to be a 17-year-old kid in urban America.

We often hear some version of this story: "Dr. Pollack, I'm so glad you are doing this. There are too many guns, too much fighting out here. My friend was shot. But you have to know something: If some guy gets in my face in the hallway, I'm going to have to kick his ass because I can't afford to allow anyone to mess with me."

Your comments are right on the money that kids' approaches can be protective in one context, but quite harmful in another. If another 17-year-old gets in your face, you might have to be tough. If that's your automatic response, things won't go well when your 11th grade English teacher gets into your face over a missing assignment.

The academic literature also suggests that aggression-prone kids aren't very good at deciphering the unspoken intentions of other people. Psychologists speak of "hostile intention attribution bias," whereby youth interpret other people's ambiguous behavior as more hostile and more threatening than it actually is.

Some of the best interventions help kids with social-emotional and self-regulation skills so that they can deal more safely and productively with each other and with adult authority figures. We've found in randomized trials that such interventions can reduce violent offending. But you can't tell kids "Don't fight." That's not realistic in their world.

I do believe that kids are exposed to some pretty toxic messages about adult masculinity. Their lack of a decent roadmap is reinforced by crummy pop culture from Chief Keef to video games to BET. Much more important, though, many of these kids don't have adult men in their everyday lives available to show them how it's done. One could write 500 Ph.D. dissertations about how hip-hop or pornography mis-socializes young men in their relationships with women. I'm not thrilled about some of what the kids are listening to or viewing. Yet the Tipper-Gore-style anxieties seem misdirected. Media dreck is much less important than the ways youth observe adult men in their lives actually treat women. Much of the hip-hop that adults dislike reflects kids' real experiences. It isn't pretty to hear, but what's coming through people's ear-buds isn't the real problem.

Why Chicago? What, specifically, do we see in the history of the city, in its style of governance, in its organization of neighborhoods, in its geography, in its policing which makes it different from New York City? It is one thing to note the high homicide rate. But why?

Why Chicago? There's no simple answer.

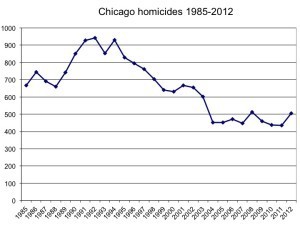

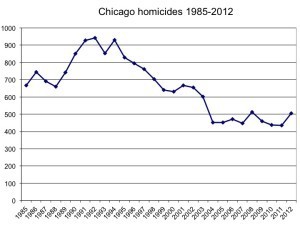

I should say at the outset that we are hardly the most dangerous city in America. We're in the middle of the pack for large cities. There's nothing happening here that people in Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, or Milwaukee aren't seeing. Our homicide rate is also below what it was 5, 10, 15, or 20 years ago (see the graph). But you can see that our homicide rate is a bit over half what it was in the early 1990s. The uptick in 2012 partly reflected random factors such as high homicide rates linked with warm weather during the early months of the year.

We still face some serious challenges. We have many more guns on the street than New York does. Per capita, CPD seizes roughly six times the guns that NYPD does.

My Crime Lab colleagues are exploring opportunities to disrupt underground gun markets. We believe that there are some real opportunities to deter straw purchasers, identify corrupt gun sellers, and more, Obviously, more work needs to be done there.

New York may be a bit ahead of Chicago in implementing innovative law enforcement strategies. Our new police superintendent is implementing some of these strategies now, and he seems on the right track. He bears some historical burdens, including such episodes as the Jon Burge police misconduct cases.

Chicago also has a pretty entrenched set of gang issues -- which is sometimes a factor in youths' gaining access to lethal weapons. Law enforcement has done a pretty good job in recent years of decapitating the major criminal organizations. Ironically, this creates new risks of violence. When once we had hierarchical organizations with a strong stake in avoiding mayhem, we now have a set of much more fractionated cliques that feud with each other and have less of a stake in containing violence.

And, of course, we have a highly segregated city with a tough history of educational failure, and deep poverty. This history was exemplified by high-rise projects such as the Robert Taylor Homes, which so scarred the landscape along highway 94. Many of these high-rises have been torn down. I believe this had to be done. It also created new challenges. I haven't seen solid numbers on this. It's clear that the relocation of so many low-income families has disrupted gang boundaries and has stressed neighborhoods within Chicago and within the collar communities just beyond the city line.

We can't use these fundamental factors as an excuse to wait in reducing crime. Indeed, crime reduction is essential to address business development and improved educational opportunities in our toughest neighborhoods. I take some heart from New York's experience. New York witnessed deep crime reductions in very poor neighborhoods that experienced many of the same economic and educational problems we see in Chicago.

The New York Times [recently had] a front page story up about Chicago, wondering how a city with "strict" gun laws can have so many guns on the street and so many murders. I found the piece a little puzzling, because it felt like the answer was right in the article -- that being that Chicago can't really control the gun laws of neighboring jurisdictions. That was also the day that Gabby Giffords comes up to the Hill along with (though not accompanying!) Wayne LaPierre.

But before jumping to that stuff I want to pick up on two points you raised toward the end of your reply. Can you talk more about the effort "to disrupt the underground markets?" What does that actually mean? What are the details that go into that? Is this mostly a matter of more arrests, targeted arrests?

And also can you talk more about -- if I may say this -- gangs as an uneasy (and unsustainable) check on rampant violence.

I'm glad that you mention that [New York Times] piece. The underlying analysis of trace data was actually performed by my terrific University of Chicago Crime Lab colleague Seth Bour. An impressive fraction of seized crime guns came from one place: Chuck's Gun Shop, located just over the city line.

[January 29 was] an especially sad day in the neighborhood just north of my office. Not far from President Obama's house, a student at King Prep high school was shot at 2:30 in the afternoon near the school. She had performed at the Inauguration.

She was apparently hanging out with her volleyball team. She was fatally shot in the back when a gunman fired into a crowd of students. A study I did with a student found that about 20 percent of Chicago gun homicide victims were clearly not the specific targets. This seems like another one of those cases.

[On the issue of underground markets,] I defer to my colleagues Phil Cook, Jens Ludwig, and colleagues who are national authorities here. Here is a terrific paper for those interested.

A few basic points.

First, many of the people we most worry about getting hold of guns are pretty unsophisticated consumers. We have good opportunities to stop these often-young people with relatively simple measures such as reverse buy-and-bust operations.

Second, the criminal justice system has traditionally not taken the underground/illegal gun market all that seriously as a distinct issue. The legal risks are pretty low on straw purchasers and on people who sell guns to people they have reasons to know might be felons. It's easy to claim that a gun was lost or stolen if you give it to someone else who then uses it in a crime.

Committing a specific violent crime with a gun is taken very seriously. Yet just being caught with a gun -- or being involved in the supply chain of the illicit gun market -- isn't taken as seriously as it should be by many in law enforcement and the courts. If one hasn't specifically used that gun to commit (another) crime, we don't always respond with the urgency that we should. If judges don't take something seriously, and if the penalties are pretty light, these offenses will receive low-priority in the queue for police and prosecutorial resources. We must treat the illicit gun markets with the full range of tools and with the same determination applied to illicit drug markets.

Some practical measures can make a real difference here. For example, President Obama is directing federal prosecutors to give these cases higher priority. I think this will help.

When an 18-year-old kills someone with a gun, very often some adult had something to say about that young man having access to a gun, or whether, when and where that young man might be carrying a loaded gun when some otherwise manageable incident escalates into a shooting. If these young men are in some way gang-affiliated, homicides are often called gang homicides. Some homicides result from explicit conflict between criminal organizations. Yet in many, many cases, the actual altercation was over some personal or family beef quite peripheral to any larger gang issue.

I tell people that the typical Chicago murder follows the equation: Two young men + stupid beef + gun = dead body. Remove the gun from that equation, and you prevent many dead bodies.

There is some evidence that focusing on these adults can be helpful in reducing certain kinds of gun crime. If, for example, a young man is gang-affiliated, we want to ensure that the adults in leadership positions within these organizations understand that they will face personal consequences if that young person commits any kind of gun crime.

I am a big believer in violence-oriented policing in considering (for example) how to manage the supply-side of the illicit drug market. No one gets a free pass. But when I prioritize resources in going after drug-selling organizations, I'm not so interested in which organization sells the most grams of heroin in a given week. I care about that, but that's not the most important thing.

I want each organization to understand that if anyone affiliated with them shoots someone, if anyone hires juveniles for street selling, if anyone intimidates the neighbors, or is otherwise an especially bad actor, the entire group will be held accountable. If these organizations get the message that violence is bad for business, I believe this will change who they hire, who in the organization is asked to be armed or to carry out violence, how they deal with disputes with other criminal organizations.

There's suggestive but hardly definitive evidence that such approaches are helpful. High Point, North Carolina, is the paradigmatic example of where such drug enforcement strategies worked pretty well. But the city of High Point is maybe the size of Ann Arbor, Michigan. It's not clear how such strategies can be translated to (say) Englewood or East Garfield Park here in Chicago.

Our new police superintendent Garry McCarthy iscognizant of these issues and is pursuing some promising approaches. Many people around the country are examining novel strategies such as those developed by David Kennedy. There's no magic bullet, but it seems to me that the quality of policing is getting better over time, and that law enforcement is taking a more discriminating approach that is more focused on evidence-based strategies to curb violence.

So let's zoom out from Chicago and talk about national policy. One of the things I've seen reported that amazed me, and a lot of other folks, was that the CDC was effectively barred by law from doing research on guns and their effects because such information could be construed as aiding gun control, or some such. Obama recently loosened some of the restrictions around research. Will that change anything? After reading this piece by Brad Plumer at Wonkblog, I'm left skeptical. Can you talk some about the constraints around gun violence research?

This isn't a cure-all. But loosening the constraints on research would help. The chilling effects of congressional meddling also goes beyond the letter of the law.

At times, policymakers and figures in the executive branch and in the public-health community have done the NRA's work for it. We've allowed second-amendment absolutists to intimidate everyone else. Researchers and public health officials saw what happened to Art Kellerman. They saw the difficulties that CDC has faced in getting pertinent research funded. Many people decided it would be easier to pick different fights.

The specific Congressional language says the following:

None of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control.

Pretty much the same language was added to the NIH budget and related health agencies.

We should take Congress's words pretty literally here. In my book, researching where crime guns come from is not promoting gun control. Conducting a randomized trial of different interventions to deter straw purchasers or to prevent gun suicide among veterans is not "advocating or promoting" gun control. Clarifying the descriptive epidemiology of real and alleged defensive use of weapons isn't advocating or promoting gun control, either. We shouldn't internalize a defensive "but what would somebody say" mentality in approaching these issues. I hope President Obama's executive orders give us greater backbone in this area.

Here's another example. Some very useful economic studies of discrimination employ random audit studies. Researchers send potential employers carefully tuned resumes of two classes of applicant. All applicants have the same formal qualifications, but one group is signaled to be African American. One can then examine whether that group is less likely to be invited for an interview. In similar fashion, well-designed audit studies could be very useful in examining the integrity of licensed or unlicensed gun dealers, and in answering other questions about underground gun markets.

Increasing the research dollars would be helpful, particularly in conducting rigorous intervention research. That's often where the research will have the biggest payoff. We've chipped away at so many causes of death and injury in America by methodically identifying and pursuing evidence-based interventions. That's true of lung cancer, sudden infant death syndrome, motor vehicle accidents, and more.

We've made less progress in firearms deaths. When one considers the tens of thousands of Americans who die every year from firearms, the CDC's budget for firearm safety and research is pathetically low.

Where does the Crime Lab stand in terms of other centers of gun violence research around the country? Some of the questions which we can't seem to answer look pretty basic -- "What percentage of gun owners even commit crimes?" for instance. Is this going to change?

These questions are indeed pretty basic, and pretty politicized. By the way, our ignorance about guns is not so unusual. Particularly in matters of intimate or stigmatized behaviors, we in the public health community often lack good answers to embarrassingly simple questions. If you ask: "How many Americans regularly inject heroin?" we're pretty uncertain. If you ask: "How many men have sex at least once per month with other men?" we're uncertain there, too. We don't always need to know these answers. We need to know enough so we can design rigorous intervention trials to see what is helpful to protect men and women in these key at-risk populations.

In gun policy, Congress creates maddening obstacles to researchers who seek to support police, judges, and prosecutors with basic law enforcement tasks. ATF's travails are also related. We mention some of those in the researchers' letter. The agency faces some truly strange restrictions on its ability to perform what we in public health would consider basic shoe-leather epidemiology in collecting and disseminating computerized data regarding crime guns or gun dealers who may be contributing to the problem. ATF needs more field agents. It needs a permanent director. It needs the same political and budgetary support we provide to the FBI for its critical law enforcement mission.

I want to come back to something else for a moment. You asked why Chicago is doing worse than L.A. or New York. As I mentioned, we're not doing worse than many other cities -- Cleveland, Detroit, Baltimore, many others. It's not Dodge City here, despite the tone of much recent coverage. Yet we are doing worse than the two cities with which we are most often compared.

No one has a definitive answer here. I would point to a few factors. First, many Midwestern cities have been hit harder by the financial crisis and the Great Recession than New York and L.A. have. New York is a much wealthier city with more extensive public services. As I mentioned, New York is certainly ahead of us in getting a handle on illegal guns.

Chicago also has a particularly nasty history of poverty and segregation in the city's south and west sides, where so many of the homicides among young African-American men and women are occurring. That history is exemplified by high-rise public housing developments such as Robert Taylor Homes. The buildings are gone, but we are still living with that.

I am sorry to keep bringing this back to Chicago, but you sort of just baited me. I'm reading The Making of the Second Ghetto right now, and I have to ask -- given how racially segregated the violence in Chicago is, is there any connection between public policy in Chicago and gun violence?

I'm glad that you are offering some props to Making of the Second Ghetto. It's an excellent book. My own university played an ambiguous role in this story. We play a much more positive role now.

You ask the broad question: is there any connection between public policy in Chicago and gun violence? That's a tough one to answer with any generality. It is certainly true that our high rates of poverty, segregation, and pervasive education failure reflect the legacy of failed public policies and discrimination.

Some of these policies go back a long way. The warehousing of African-American families in public housing and overt discrimination within Chicago Public Schools still cast long shadows. (Kathy Neckerman's Schools Betrayed describes the history of Chicago Public Schools.) Chicago is sometimes called the City That Works, a backhanded tribute to the political machine that dominated city politics for decades. In so many basic respects, the City didn't work for many people here.

Some of this problematic legacy stems from a more recent past. Police need active community cooperation to solve many crimes. Episodes such as the Jon Burge case really hurt that effort. Several years ago, I spoke with Louis Farrakan about youth crime issues. He offered the thought that nothing happened at Abu Ghraib that hadn't happened in station-house basements at CPD. These abuses occurred in a different time. Their effects linger.

Chicago's political economy -- like that of many cities -- channels resources to the most organized and prosperous neighborhoods. That's life in urban America. Every mayor in America -- whatever his or her ideology -- must cater to mobile affluent families and firms that support the tax base and a city's economic life. If we aren't careful, the end result can be to channel disproportionate police manpower, disproportionate educational, recreation, and other investments to upscale communities rather than to the places that need these resources the most. This would be a disaster -- particularly in a time of limited federal support for urban job programs and other supports we desperately need.

To its credit, CPD has instituted processes such as Comstat that counter this political inertia. The "cops on the dots" approach holds everyone accountable to place the police where crimes actually occur. Frank Zimring's book, The City that Became Safe, noted the same democratizing pattern in New York. New York's crime rate went down in its toughest community. One reason for that was the real improvement in police protection for these places.

Two other issues deserve mention. Failed national housing policies have really hammered Cook County's African-American communities. The same heavily-segregated African-American communities that top the homicide statistics dominate the list of communities checker-boarded with foreclosed or abandoned properties. It's hard to stabilize a community to address crime when this is the economic reality. I myself live in a predominantly African-American neighborhood within the south suburbs. Many houses on our neighborhood stand empty or are in various stages of foreclosure. It wouldn't surprise me if median household wealth among African Americans here has gone negative.

We send out many other large and small messages that marginalize young men and women of color. A friend of mine runs a sports intervention for low-income youth. He noted something I had never noticed, hidden in plain sight. Milennium Park and its surroundings-- genuinely beautiful triumphs of Mayor Daley's tenure - include wonderful gardens, tennis courts, an ice-skating rink. They don't include a single basketball court. The Chicago Parks District website indicate no outdoor basketball courts in the Loop area.

Young couples of every income and color stroll to Buckingham Fountain and its environs. By and large, though, this is pretty upscale turf. Few amenities are designed to draw minority teenagers down to the Loop.

I do want to ask you about some cultural matters.

What shall we make of the tougher edges of hip-hop and pop culture consumed by young people? One can over-react to this. Much of the raunchiness of hip-hop is a reflection rather than a cause of the tough conditions in urban life. Still, I do worry that American youth are fed some pretty toxic messages about gender, violence, and other matters. I've always thought that immigrants and outsiders enjoy a real advantage because they are a bit more insulated from the dreck of American youth culture.

It's not crazy to worry that African-American and Latino youth are particularly harmed by this stuff. The youth workers I know are quite concerned, for example, when rappers such as Chief Keef clown around with guns on video.

As a parent and as a social commentator, how do you think about these issues? Are they overblown? Is there some sensible sense that avoids Tipper-Gore-style prudishness but that also avoids naïve cultural complacency?

So glad you asked this question -- especially given my full-throated endorsement of Kendrick Lamar. I don't think they're overblown, so much as I think they're misunderstood. I can't really vouch for Chief Keef. I haven't given him a good listen. But one major mistake that I think people make with hip-hop -- and perhaps with pop culture at large -- is that they tend to think of it as promoting certain values. It's easy to make that assumption given the actual lyrics which do involve exulting the life of the urban outlaw and all its attendant aspects. Mastering and dispensing violence is a large part of that. But I think it's worth asking, "Why do kids listen to violent hip-hop?" I highly doubt the answer is "To find an applicable value system." As someone who had NWA's first album, and gas fond memories of the Geto Boys, I would suggest that what the kids go there for -- beyond the beat of the music -- is fantasy.

I don't think hip-hop so much reflects these violent neighborhoods, as it serves as therapy for the young boys who live in them. It offers a vicarious world where every puerile desire is instantly met. If you listen really closely to music, you will hear it pulsing with teenage insecurity and the angst of the youth. In hip-hop, young people are able to express sentiments and feelings, many of them negative, which they can't really express elsewhere. Living, from the time you are born, with the threat of existential violence is stressful. Stress leads to anger and fear. We don't generally express our anger and fear by saying, "I love the world" or "I pray for an end to world hunger." Living around violence might make you say those things. But the stress of it more often will probably leave you with a string of curse words on your tongue. Moreover, it might even make you want to convert all of those negative feelings into a persona which can't be killed by other males, which never feels rejection from females, and is generally free to engage all its hedonistic desires.

I think that's right. Of course, much of the critique of hip-hop confuses effects for causes here. The nihilism in the music stems from the nihilistic real-world environment, not the other way around. There's also certain troubling feedback loop, whereby the music you turn to for release and otherwise-forbidden expression of your reality may be psychically problematic. Adults figured out a long time ago that there's a buck to be made on MTV or BET from calibrated excesses that hit the lowest common denominator in youth culture. You can make more money hawking sex and violence than you can by depicting what happens two years after the bullets go flying, when a shooter sits in an 8x12 cage, and the victim is left wearing a colostomy bag.

I have to say, I'm 37 now. And there's certainly stuff I can't listen to. But when I was in the target age rage I was boiling over with angst. Hip-hop was where I went to work it out. My son listens to a lot of bad music that does the same for him. I would never stop him from doing that. But I do try to engage him. I'll tell you a story: When I was 14 I had an NWA album which included a song about oral sex which was really degrading to women. I was listening to it in my Walkman one day in the car, while my dad was driving. He asked what I was listening to and then told me to put it in the tape-deck. I reluctantly did this. We listened and then he gave me a long forceful talk about how women should be regarded. But more importantly, he handed the tape back to me. He left me with a choice and the choice wasn't over where to get my values from, it was over what fantasies I would countenance and what fantasies I wouldn't.

This is a great story, which underscores (among other things) the role of the actual adult human beings in kids' lives. We're the ones who ignore, moderate, or aggravate whatever broader influences reach our kids from other places. As I mentioned, I have two daughters, age 18 and age 16. I hate to think that their boyfriends and future marriage partners are learning about women from music videos or the Sports Illustrated bathing suit issue. Yet what really matters is what these young men hear and see among the adults around them.

My great fear is for kids who just don't have an adult around them to show the way.

Again as I mentioned, we recently performed a successful randomized trial for an intervention called "Becoming a Man, Sports Edition." This program is fielded by two local nonprofits, Youth Guidance and World Sport Chicago. It features once-per-week group sessions with well-trained adult mentors and coaches for after-school sports programming. We found that the program significantly reduced violent offending, and significantly improved school engagement. Just today, Mayor Emanuel is announcing $2 million in city funds to expand this program.

We on the research team have been struck by one simple question: Why is this rather modest, non-intensive intervention so effective? There are many reasons. But the most basic is that young men in tough Chicago neighborhoods have such limited access to appealing and engaged adult men who can help them navigate the tough world in which they live.

I think it's worth asking whether we as adults are any different than our kids. America consumes massive amounts of pornography. Why? Isn't a some of this about male frustration at having to actually "work" for the sexual attention of women? Porn constructs a world where no work is needed. It's all right there. If we know broad swaths of men seek out such fantasies, why do expect kids -- laboring under much more stressful circumstances -- to be different?

Yes indeed. I would also note that the same market actors who hawk alcohol and tobacco on 67thh street in Chicago are only too happy to market "titles do not show up on your hotel bill" films eighty streets uptown on Michigan Avenue near the fancy convention spots. Is pornography actively harmful? I don't know. I certainly hope the young men in Evanston and Hyde Park have some adult men showing them the way, too.

The American Story Behind Gangs and Gun Violence

Learning from University of Chicago Crime Lab's Harold Pollack, a man who helped make the misuse of firearms a public health issue

Outside the funeral for Hadiya Pendleton, the Obama inauguration performer killed by a gunman in a Chicago park on January 29 (John Gress/Reuters)

Outside the funeral for Hadiya Pendleton, the Obama inauguration performer killed by a gunman in a Chicago park on January 29 (John Gress/Reuters) Like everyone, we at The Atlantic have spent the weeks since Newtown thinking about the role of guns in America. In our ongoing effort to broaden the conversation, I spent some time talking to Professor Harold Pollack, who co-directs the Crime Lab at the University of Chicago. Pollack is one of the foremost voices on gun violence from a public health perspective. Pollack and his colleagues at the Crime Lab have done yeoman's work in helping us understand how guns end up on the streets of cities like Chicago, and how precisely they tend to be used.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Hi, Harold. Thanks so much for taking the time to join us over here at The Atlantic. We've had several off-line conversations which have been illuminating to me. I greatly appreciate your willingness to take some time to do this for the Horde, as we say on the blog.

Harold Pollack: It's great to correspond with you, Ta-Nehisi, regarding what can actually be done to reduce gun violence. I'm a big fan of your work. I should mention by way of self-introduction that I am a public health researcher at the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration and co-director of the University of Chicago Crime Lab.

Here in Chicago, we have become the focus of much national attention because we had our 500th homicide [of the year in 2012]. We're sometimes called the nation's murder capital -- though this mainly reflects the fact that we are a big city. We're more dangerous than L.A. or New York, but we're actually in the middle of the pack when it comes to homicide rates. Still, we're dangerous enough. The declining homicide rates in many prosperous and middle-class neighborhoods casts a harsh light on the high rates facing African-American (and to a lesser-extent) Latino young men on the city's south and west sides. Lots to talk about. I am looking forward to talking. So let's get to it.

I don't know if I've told you how I come to this issue, but I should say for everyone reading this that I am from Baltimore -- the West Side, as we used to call it. I came of age in the late 1980s and early 90s, a period in which violence spiked in our cities. I don't know if Chicago today is as bad as it was in, say, 1988, but this was a period of deep fear for everyone in the black communities of Baltimore. And the fear was everywhere.

It changed how we addressed our parents. It changed how we addressed each other. It changed our music. The violence put rules in place that often look strange to the rest of the country. For instance, the mask of hyper-machismo and invulnerability -- the ice-grill, as we used to say -- looks strange, until you've lived in a place where that mask is the only power you have to effect a modicum of safety.

I'm in my late 40s. I was a typical suburban kid graduating high school outside New York. It wasn't as tough for me as it was on the west side of Baltimore, but crime certainly touched my life. On one occasion, I was in Washington Heights on my way to an AP class at Columbia University. A group of middle-school or early-high-school kids jumped me in the subway station, and they attempted to wrest away my watch. My high school sweetheart had just given it to me; I didn't want to give it up. So a kid grabbed me by the hair and smashed my head against the concrete floor until I finally relented. As you know, my cousin was beaten to death by two teenage house burglars a few years later.

So I remember very well both the fear and the anger that accompanies one's sense of physical vulnerability. Of course this anger often comes with a race/ethnic/class tinge that poisons so much of what we are trying to do in revitalizing urban America.

It's odd. I sometimes travel in some pretty tough neighborhoods, and it's been maybe 20 years since someone has laid an unfriendly hand on me. The gray hair seems to put me in a different category. The kids we encounter are sometimes a bit struck that one can be a shrimpy, nerdy guy and be a successful adult man. That option doesn't seem as open to them.

I remember when Allen Iverson came into the NBA and people could not understand why he walked around with twenty dudes. I totally understood, and I suspect a lot of black males did too. But one thing that's become clear to me, and that I've tried to grapple with in my blogging, is that cultural practices that offer some protection in one place are often quite harmful in another. Iverson's clique may have saved him countless times in Virginia Beach. But in that broader world, they sometimes empowered his worst urges. So much of my work is about how young black males negotiate violence, and how those negotiations affect them when they interact with the broader world.

I get a sense of that when I talk with young men in Chicago who participate in violence prevention efforts. Kids are wearing that ice-grill for some very real reasons in their world. It's just a tough assignment to be a 17-year-old kid in urban America.

We often hear some version of this story: "Dr. Pollack, I'm so glad you are doing this. There are too many guns, too much fighting out here. My friend was shot. But you have to know something: If some guy gets in my face in the hallway, I'm going to have to kick his ass because I can't afford to allow anyone to mess with me."

Your comments are right on the money that kids' approaches can be protective in one context, but quite harmful in another. If another 17-year-old gets in your face, you might have to be tough. If that's your automatic response, things won't go well when your 11th grade English teacher gets into your face over a missing assignment.

The academic literature also suggests that aggression-prone kids aren't very good at deciphering the unspoken intentions of other people. Psychologists speak of "hostile intention attribution bias," whereby youth interpret other people's ambiguous behavior as more hostile and more threatening than it actually is.

Some of the best interventions help kids with social-emotional and self-regulation skills so that they can deal more safely and productively with each other and with adult authority figures. We've found in randomized trials that such interventions can reduce violent offending. But you can't tell kids "Don't fight." That's not realistic in their world.

I do believe that kids are exposed to some pretty toxic messages about adult masculinity. Their lack of a decent roadmap is reinforced by crummy pop culture from Chief Keef to video games to BET. Much more important, though, many of these kids don't have adult men in their everyday lives available to show them how it's done. One could write 500 Ph.D. dissertations about how hip-hop or pornography mis-socializes young men in their relationships with women. I'm not thrilled about some of what the kids are listening to or viewing. Yet the Tipper-Gore-style anxieties seem misdirected. Media dreck is much less important than the ways youth observe adult men in their lives actually treat women. Much of the hip-hop that adults dislike reflects kids' real experiences. It isn't pretty to hear, but what's coming through people's ear-buds isn't the real problem.

Why Chicago? What, specifically, do we see in the history of the city, in its style of governance, in its organization of neighborhoods, in its geography, in its policing which makes it different from New York City? It is one thing to note the high homicide rate. But why?

Why Chicago? There's no simple answer.

I should say at the outset that we are hardly the most dangerous city in America. We're in the middle of the pack for large cities. There's nothing happening here that people in Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, or Milwaukee aren't seeing. Our homicide rate is also below what it was 5, 10, 15, or 20 years ago (see the graph). But you can see that our homicide rate is a bit over half what it was in the early 1990s. The uptick in 2012 partly reflected random factors such as high homicide rates linked with warm weather during the early months of the year.

We still face some serious challenges. We have many more guns on the street than New York does. Per capita, CPD seizes roughly six times the guns that NYPD does.

My Crime Lab colleagues are exploring opportunities to disrupt underground gun markets. We believe that there are some real opportunities to deter straw purchasers, identify corrupt gun sellers, and more, Obviously, more work needs to be done there.

New York may be a bit ahead of Chicago in implementing innovative law enforcement strategies. Our new police superintendent is implementing some of these strategies now, and he seems on the right track. He bears some historical burdens, including such episodes as the Jon Burge police misconduct cases.

Chicago also has a pretty entrenched set of gang issues -- which is sometimes a factor in youths' gaining access to lethal weapons. Law enforcement has done a pretty good job in recent years of decapitating the major criminal organizations. Ironically, this creates new risks of violence. When once we had hierarchical organizations with a strong stake in avoiding mayhem, we now have a set of much more fractionated cliques that feud with each other and have less of a stake in containing violence.

And, of course, we have a highly segregated city with a tough history of educational failure, and deep poverty. This history was exemplified by high-rise projects such as the Robert Taylor Homes, which so scarred the landscape along highway 94. Many of these high-rises have been torn down. I believe this had to be done. It also created new challenges. I haven't seen solid numbers on this. It's clear that the relocation of so many low-income families has disrupted gang boundaries and has stressed neighborhoods within Chicago and within the collar communities just beyond the city line.

We can't use these fundamental factors as an excuse to wait in reducing crime. Indeed, crime reduction is essential to address business development and improved educational opportunities in our toughest neighborhoods. I take some heart from New York's experience. New York witnessed deep crime reductions in very poor neighborhoods that experienced many of the same economic and educational problems we see in Chicago.

The New York Times [recently had] a front page story up about Chicago, wondering how a city with "strict" gun laws can have so many guns on the street and so many murders. I found the piece a little puzzling, because it felt like the answer was right in the article -- that being that Chicago can't really control the gun laws of neighboring jurisdictions. That was also the day that Gabby Giffords comes up to the Hill along with (though not accompanying!) Wayne LaPierre.

But before jumping to that stuff I want to pick up on two points you raised toward the end of your reply. Can you talk more about the effort "to disrupt the underground markets?" What does that actually mean? What are the details that go into that? Is this mostly a matter of more arrests, targeted arrests?

And also can you talk more about -- if I may say this -- gangs as an uneasy (and unsustainable) check on rampant violence.

I'm glad that you mention that [New York Times] piece. The underlying analysis of trace data was actually performed by my terrific University of Chicago Crime Lab colleague Seth Bour. An impressive fraction of seized crime guns came from one place: Chuck's Gun Shop, located just over the city line.

[January 29 was] an especially sad day in the neighborhood just north of my office. Not far from President Obama's house, a student at King Prep high school was shot at 2:30 in the afternoon near the school. She had performed at the Inauguration.

She was apparently hanging out with her volleyball team. She was fatally shot in the back when a gunman fired into a crowd of students. A study I did with a student found that about 20 percent of Chicago gun homicide victims were clearly not the specific targets. This seems like another one of those cases.

[On the issue of underground markets,] I defer to my colleagues Phil Cook, Jens Ludwig, and colleagues who are national authorities here. Here is a terrific paper for those interested.

A few basic points.