Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog, page 55

March 23, 2013

Departures Cont.

II. Vendredi

I have come to regard anyone who speaks more than one language as the bearer of great and unearned power. You say bilingualism and I imagine ice sleds, healing factors and flight. In New York, I am surrounded by the secret schoolmen of Salem. They speak and and my fingers dabble at the inhibitor collars.

I am deep in my dark and twisted lab. I am building a machine of fantastic power and awesome savoir-faire. Soon I shall flip a switch, and all those who laughed at my "Parlay-vouz" and "Jay Nay Say Pahs" shall turn, light leaping from them into the cone of my terrible device. Then they will stagger before brilliant me, blinking and depowered. For now I just murmur "Mutie scum" under my breath and bide my time.

I am in Geneva, like the only human on Asteroid M. They told me that the people would switch to English as soon as they heard my French. But this only happens when we are discussing money. An entire conversation will go over in French. Then from out of nowhere a merchant will say "twenty-five" and then there is nothing but French. I was unprepared for the loneliness of thought. The only spoken English is in my head.

But people were as people usually are--kind. I expected less black folks. But they were there. They did not nod, or flash a secret sign, as they sometimes didd back home. There's no real reason for them to do so. Skin prejudice in America is a specific thing, which is different than saying skin prejudice in America is a unique thing. How it shows up in Switzerland (beyond the obvious) I don't know. But I made no assumptions.

I took a train into Paris--just under four hours--then the subway to my hotel. Here, the manager could smell of America wafting off of me and spoke to me in English.

"You won't mind if I inflict my terrible French on you, will you?" I said.

"Not everyone can speak French," she said politely laughing.

"Not yet freak," I thought. "The ion correlator still needs work."

I showered. Rested. Changed clothes. Walked the streets. No one should ever write a single word about Paris ever again. Everything has surely been said. Forgive me for all that follows here.

It was Friday. The blocks were overcome with people. The people came in all configurations. Teenagers together. Schoolchildren kicking a soccer-ball on the street, backpacks to the side. Older couples in long coats, scarves and blazers. Twenty-somethings leaning out of any number of establishments looking beautiful and cool. It reminded me of New York, but without the low-grade, ever-present, fear. The people wore no armor, or none that I knew. I was in the sixth arrondissement. I felt myself melting in the stew of it all. There were whole blocks which had doubtlessly sprouted a generation of poorly-executed romantic comedies, though they seemed a good idea at the time. Side-streets and alleys were bursting with bars, restaurants and cafes. Everyone was walking. Those who were not walking were embracing.

I was feeling myself beyond any actual right. I was rocking a blue blazer, a mint-green button down and wing-tips. I had traded my writer's beard for a caesar sharp as the Wu-Tang sword. In my head I heard Big-Boi sing "Sade in the tape deck, I'm moving in slow motion."

I was walking with a homeboy from Brooklyn, who'd lived here for many years. We passed a row of restaurants. A man in jeans in New Balance bade us in. The establishment was the size of two large living rows. The tables were jammed together and to be seated, the waitress had to pull one table out so that you could be wedged in. She did this by a kind of magic known only to her. You had to summon her to use the toilet. The waitress was nice, but did not flatter us. When my French failed she spoke through my friend. There were no false manners, nor ceremony. She was not there to make me feel like a king. I found all of that to be clarifying and oddly soothing.

Everyone here seemed over 25.

We had an incredible bottle of wine. I had steak. I had a baguette accompanied with a kind of fat made from beef marrow. I had liver. I had expresso and a desert which I can't even name. In all the French I could muster I tried to tell the waitress the meal was magnificent. She cut me off, "The best you've ever had, right?" I nodded. This was true and not true all at once. What I will say is that when I rose to walk, despite inhaling half the menu, I felt light as a boxer.

All that day I saw interracial couples around me. I did not notice them, so much as I noticed myself. It felt off--like someone noting that I am from Baltimore and Kenyatta from Chicago, and then dubbing us an "intergeographic couple." In another reality (maybe even in an another country) we could be an "interracial couple." The import of all this lives not in the blood, but in a system created by recent men of recent power, who decided that skin-color prejudice was an advantageous way of organizing the world. We adopt words to defend ourselves, and somehow reify our enemies. I think "Interracial couple" and know that I have said something of where I am from. But I wonder what I have said about the couple themselves.

I feel, all at once, that I am not a race and but that I am from somewhere. That place--a nation called black America--shapes my mannerism and speech, my world-view and words, my aesthetics. More, I believe in being from somewhere. I believe in patriotism. But I don't experience this present birth of cosmopolitanism as a threat.

How can that be?

This comes to me as wholly unoriginal--a crisis not born of blackness, but born of humanity, a crisis of being from somewhere. I turn this over in my head and feel that I am hearing words from some great essay I was too lazy to read. Baldwin? Said? What I am feeling something I can't quite name, something beyond the Fuzzy Zoeller, fried chicken and Tiger Woods.

I am back at the lab. I need another language. I need more power. I need a big machine.

March 22, 2013

Departures Cont.

II. Vendredi

I have come to regard anyone who speaks more than one language as the bearer of great and unearned power. You say bilingualism and I imagine ice sleds, healing factors and flight. In New York, I am surrounded by the secret schoolmen of Salem. They speak and and my fingers dabble at the inhibitor collars.

I am deep in my dark and twisted lab. I am building a machine of fantastic power and awesome savoir-faire. Soon I shall flip a switch, and all those who laughed at my "Parlay-vouz" and "Jay Nay Say Pahs" shall turn, light leaping from them into the cone of my terrible device. Then they will stagger before brilliant me, blinking and depowered. For now I just murmur "Mutie scum" under my breath and bide my time.

I am in Geneva, like the only human on Asteroid M. They told me that the people would switch to English as soon as they heard my French. But this only happens when we are discussing money. An entire conversation will go over in French. Then from out of nowhere a merchant will say "twenty-five" and then there is nothing but French. I was unprepared for the loneliness of thought. The only spoken English is in my head.

But people were as people usually are--kind. I expected less black folks. But they were there. They did not nod, or flash a secret sign, as they sometimes didd back home. There's no real reason for them to do so. Skin prejudice in America is a specific thing, which is different than saying skin prejudice in America is a unique thing. How it shows up in Switzerland (beyond the obvious) I don't know. But I made no assumptions.

I took a train into Paris--just under four hours--then the subway to my hotel. Here, the manager could smell of America wafting off of me and spoke to me in English.

"You won't mind if I inflict my terrible French on you, will you?" I said.

"Not everyone can speak French," she said politely laughing.

"Not yet freak," I thought. "The ion correlator still needs work."

I showered. Rested. Changed clothes. Walked the streets. No one should ever write a single word about Paris ever again. Everything has surely been said. Forgive me for all that follows here.

It was Friday. The blocks were overcome with people. The people came in all configurations. Teenagers together. Schoolchildren kicking a soccer-ball on the street, backpacks to the side. Older couples in long coats, scarves and blazers. Twenty-somethings leaning out of any number of establishments looking beautiful and cool. It reminded me of New York, but without the low-grade, ever-present, fear. The people wore no armor, or none that I knew. I was in the sixth arrondissement. I felt myself melting in the stew of it all. There were whole blocks which had doubtlessly sprouted a generation of poorly-executed romantic comedies, though they seemed a good idea at the time. Side-streets and alleys were bursting with bars, restaurants and cafes. Everyone was walking. Those who were not walking were embracing.

I was feeling myself beyond any actual right. I was rocking a blue blazer, a mint-green button down and wing-tips. I had traded my writer's beard for a caesar sharp as the Wu-Tang sword. In my head I heard Big-Boi sing "Sade in the tape deck, I'm moving in slow motion."

I was walking with a homeboy from Brooklyn, who'd lived here for many years. We passed a row of restaurants. A man in jeans in New Balance bade us in. The establishment was the size of two large living rows. The tables were jammed together and to be seated, the waitress had to pull one table out so that you could be wedged in. She did this by a kind of magic known only to her. You had to summon her to use the toilet. The waitress was nice, but did not flatter us. When my French failed she spoke through my friend. There were no false manners, nor ceremony. She was not there to make me feel like a king. I found all of that to be clarifying and oddly soothing.

Everyone here seemed over 25.

We had an incredible bottle of wine. I had steak. I had a baguette accompanied with a kind of fat made from beef marrow. I had liver. I had expresso and a desert which I can't even name. In all the French I could muster I tried to tell the waitress the meal was magnificent. She cut me off, "The best you've ever had, right?" I nodded. This was true and not true all at once. What I will say is that when I rose to walk, despite inhaling half the menu, I felt light as a boxer.

All that day I saw interracial couples around me. I did not notice them, so much as I noticed myself. It felt off--like someone noting that I am from Baltimore and Kenyatta from Chicago, and then dubbing us an "intergeographic couple." In another reality (maybe even in an another country) we could be an "interracial couple." The import of all this lives not in the blood, but in a system created by recent men of recent power, who decided that skin-color prejudice was an advantageous way of organizing the world. We adopt words to defend ourselves, and somehow reify our enemies. I think "Interracial couple" and know that I have said something of where I am from. But I wonder what I have said about the couple themselves.

I feel, all at once, that I am not a race and but that I am from somewhere. That place--a nation called black America--shapes my mannerism and speech, my world-view and words, my aesthetics. More, I believe in being from somewhere. I believe in patriotism. But I don't experience this present birth of cosmopolitanism as a threat.

How can that be?

This comes to me as wholly unoriginal--a crisis not born of blackness, but born of humanity, a crisis of being from somewhere. I turn this over in my head and feel that I am hearing words from some great essay I was too lazy to read. Baldwin? Said? What I am feeling something I can't quite name, something beyond the Fuzzy Zoeller, fried chicken and Tiger Woods.

I am back at the lab. I need another language. I need more power. I need a big machine.

March 21, 2013

Departures

Yesterday I ate a bad nut on the train to Boston and went into anaphylactic shock. A doctor who happened to be seated nearby shot me up with a epipen. The train made an emergency stop in New London where the paramedics were waiting. I was shivering crazily, which was better than the bullets I'd been sweating moments before. The doc told me it was the adrenaline. I kept apologizing. I couldn't believe I was making a scene on the Quiet Car.

The paramedics came in and took my blood pressure. They were moving to get me on a stretcher. I told them I could stand. They told me I could not as my blood pressure was such that I would likely faint. So they hauled me up and off, got me to the hospital, ran some oxygen through my nose and put an IV in my arm. When I got the hospital the doctors took great care of me. Two points: First, my theory of assholes clearly should be revised; the kindness of strangers is always amazing. Second, America, whatever its flaws, is very often amazing in its efficiency and compassion. It did not escape my mind that in some other place I might have died. This is not chest-thumping or jingoism. It is a fact of my residency.

Through it all, I could only think of one thing: Will I get to Europe? The doctor came in after I'd awaken. My swelling had gone down. But the drop in blood pressure spooked him. After some deliberation he released me and told me if I had no problems over the next 24 hours, I would be fine to fly.

I have not had any problems. At 8:45 I will board a ship. It will punch through the sky. At some point, God willing, that ship will emerge over airspace far from the beloved West Baltimore of my youth. Something is happening in this world. I think of my grandfather, lecturing from the daily newspaper, drowning in alcohol, addicted to violence. I think of my father, working all summer as a child, saving his funds for a collection of recordings that promised to teach him French. He didn't learn French, but he learned to compel his son to want to learn French. I think of my grandmother pushing up from the Eastern Shore of Maryland raising three daughters in the projects, somehow sending them all to college.

I think of what these folks might have been had they not lived in world intolerant of black ambition. The world has changed. It has not changed totally, but it has changed significantly. When I fell out on the train, everyone on the car was white. So were all the paramedics and all the doctors and nurses. The challenge for someone trying to assess America, at this moment, is properly calibrating how far we've gone with how far we have to go. Too much optimism renders you naive; too much pessimism makes you cynical.

Je ne sais pas. What I know is I live in a time that people who made me possible only dreamed of. And then yesterday I almost lost it all. Today I called the doctor who assisted me on the train. He told me that by some act of magic the guy behind him had an epipen. He had no idea what would have happend if not for that fact. I remember standing in the bathroom thinking, I don't need to tell anyone. This will pass. And then my vision started going. I stumbled out of the bathroom and said, "I need help." After I laid down, I heard the doctor say, "I can't get a pulse." This is something no one ever wants to hear.

But I have seen the elephant now. It would not have been the worst way to go, but it would have been going all the same. And I am most happy to still be here, to be with my family, and my friends, to be in the world with you. I'm not very good with crisis. I tend not to grasp the import until years later.

For now, I am off to partake in an adventure, armed with a sack of meds, the works of Brendan Koerner, Ursala Le Guin, Antony Beevor and enough French to defend myself. I look forward to reporting back in the days to come.

March 20, 2013

The Iraq War and History as Self-Flattery

After Pearl Harbor, after Vietnam, after World War II, after the 9/11 attacks, even after civilian disasters like the Challenger explosion or Katrina, there were official efforts, of varying seriousness and success, to find out what had gone wrong, and why, and to yield "lessons learned." That hasn't happened this time, for a lot of reasons. For the Bush Administration, there was no "failure" to be examined and explained. For the Obama Administration, the point was to "look forward not back." People in the media and politics who were against the war know that it can grow tiresome to keep pointing that out.Fallows's piece is all about the failure of Americans to revisit an important episode in our history. For those of us who've spent a good deal of time discussing the pernicious effects of racism, "look forward not back" is a familiar phrase. It's usually stated as thought it were some inviolable and honorable principle, when in fact it is an effort to escape accountability. As I said yesterday, it's not so much that we don't want to "look back" so much as we don't want to "look back" on things that might demand onerous labor on our part. Faced with a credit-card bill, I have often thought to suggest we should "look forward not back." Faced with a paycheck, not so much.

Example: Barack Obama would not be president today if he had not given a speech in Chicago in October 2002, saying that he (as a mere state senator) did not oppose all wars but was against a "dumb" and "rash" war in Iraq. Listen to how he talked in those days! He also denounced "the cynical attempt by Richard Perle and Paul Wolfowitz and other armchair, weekend warriors in this administration to shove their own ideological agendas down our throats, irrespective of the costs in lives lost and in hardships borne." Because of that speech, six years later Obama could argue that his judgment had been right, and the vastly more experienced HIllary Clinton's had been wrong, about matters of war and peace. But there's no percentage for him in bringing that up now.

What separates the Iraq War from everything else Jim mentions here, is that it indicts not just an administration, but an entire class of "Serious People." These people tend to be powerful and they are insulated by the distance increasing distance between those who agitate for wars and those who fight them. They are insulated by the death of 120,000 Iraqi civilians. Given that, Jim is probably right. It will almost certainly happen again.

The Iraq War And History As Self-Flattery

After Pearl Harbor, after Vietnam, after World War II, after the 9/11 attacks, even after civilian disasters like the Challenger explosion or Katrina, there were official efforts, of varying seriousness and success, to find out what had gone wrong, and why, and to yield "lessons learned." That hasn't happened this time, for a lot of reasons.Fallows piece is all about the failure of Americans to revisit an important episode in our history. For those of us who've spent a good deal of time discussing the pernicious effects of racism, "look forward not back" is a familiar phrase. It's usually stated as thought it were some inviolable and honorable principle, when in fact it is an effort to escape accountability. As I said yesterday, it's not so much that we don't want to "look back" so much as we don't want to "look back" on things that might demand onerous labor on our part. Faced with a credit-card bill, I have often thought to suggest we should "look forward not back." Faced with a paycheck, not so much.

For the Bush Administration, there was no "failure" to be examined and explained. For the Obama Administration, the point was to "look forward not back." People in the media and politics who were against the war know that it can grow tiresome to keep pointing that out.

Example: Barack Obama would not be president today if he had not given a speech in Chicago in October 2002, saying that he (as a mere state senator) did not oppose all wars but was against a "dumb" and "rash" war in Iraq. Listen to how he talked in those days! He also denounced "the cynical attempt by Richard Perle and Paul Wolfowitz and other armchair, weekend warriors in this administration to shove their own ideological agendas down our throats, irrespective of the costs in lives lost and in hardships borne." Because of that speech, six years later Obama could argue that his judgment had been right, and the vastly more experienced HIllary Clinton's had been wrong, about matters of war and peace. But there's no percentage for him in bringing that up now.

What separates the Iraq War from everything else Jim mentions here, is that it indicts not just an administration, but an entire class of "Serious People." These people tend to be powerful and they are insulated by the distance increasing distance between those who agitate for wars and those who fight them. They are insulated by the death of 120,000 Iraqi civilians. Given that, Jim is probably right. It will almost certainly happen again.

March 19, 2013

The Ghetto Is Public Policy

But the most affecting aspect of the book is the demonstration of the ghetto not as a product of a violent music, super-predators, or declining respect for marriage, but of policy and power. In Chicago, the ghetto was intentional. Black people were pariahs whom no one wanted to live around. The FHA turned that prejudice into full-blown racism by refusing to insure loans taken out by people who live near blacks.

Contract-sellers reacted to this policy and "sold" homes to black people desperate for housing at four to five times its value. I say "sold" because the contract-seller kept the deed, while the "buyer" remained responsible for any repairs to the home. If the "buyer" missed one payment they could be evicted, and all of their equity would be kept by the contract-seller. This is not merely a matter of "Of." Contract-sellers turned eviction into a racket and would structure contracts so that sudden expenses guaranteed eviction. Then the seller would fish for another black family desperate for housing, rinse and repeat. In Chicago during the early 60s, some 85 percent of African-Americans who purchased home did it on contract.

These were not broken families in need of a lecture on work ethic. These were black people playing by the rules. And for their troubles they were effectively declared outside the law and thus preyed upon.

Americans did not escape the implications of racist public policy. Here is Satter foreshadowing much of what we see in today's housing crisis:

[B]y the late 1960s, the system began to falter. Buildings were in such a sorry state that buyers were increasingly likely to put $100 down, make a few months of high payments, and then, overwhelmed by the avalanche of expenses necessary to make their new homes livable, abandon the properties. Without steady contract payments, Lawndale's contract sellers had no intention of continuing to pay their own mortgages.In the interest of racism, the American taxpayer ended up bankrolling a massive fraud perpetrated on black communities in Chicago. It gets worse:

Instead, they defaulted on their loans, dumping hundreds of crumbling, overmortgaged buildings back onto the lending institutions. Since the near-ruined buildings were now worth only a fraction of the original loans, the institutions essentially lost their loan money, amounting to millions of dollars. These losses pushed First Mutual to the point of collapse. Desperate to recoup something, the company offered the buildings for sale, at "rock bottom prices," to whoever would take them.

The scavengers who gathered to buy were often the same men who had dumped them in the first place. In one day alone, Moe Forman turned six slums over to First Mutual; five of the six ended up back in his hands, with Gil Balin as copartner. Al Berland dumped approximately sixty buildings onto First Mutual and then repurchased them at a fraction of their former worth.

By 1968, First Mutual was out of business, and 659 of its defaulted mortgages--worth $7.8 million--landed with the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC), the governmental agency that insured savings and loan deposits. Many of these debts had been owed by Lawndale's worst contract sellers. They included $756,920 in delinquent mortgages owed by Berke, $280,000 by Berland, $502,323 by Forman's F & F Investment company, $28,945 by Forman himself, and $241,658 by Fushanis's estate.

Some observers found it difficult to understand why Forman and his circle were so eager to reclaim the buildings they had so recently shed. "Slums don't pay. If there was a conspiracy, it was stupid," claimed Pierre DeVise, an urbanologist who taught at the University of Illinois in Chicago. In fact, the "stupid" one was probably DeVise. As the Tribune commented, "Such disbelief ... has been the slumlords' greatest ally." For those ruthless enough to stomach the consequences, it was easy to make profits out of buildings for which one paid cash and on which one owed nothing. As Timothy O'Hara pointed out, "If you're not making repairs ... you are making 100 percent profit."One retort that people often make when discussing the history of racism is "We should not dwell on the past." It's an opportunistic claim--no one looks at July 4 and says "We should not dwell on the past." But more to the point, this is not the distant past. The men and women who suffered at the hands of the FHA and the racist aspects of New Deal legislation are very much alive today. Furthermore, their children are alive and the effects of that policy on the country are fairly obvious. We know what we want to know. We believe the ghetto is manifestation of individual will and amorphous culture values because that is what we would prefer to think. It's not so much that we don't want to dwell on the past, so much as we want to choose our past.

However, O'Hara noted a growing trend among slum landlords: to "avoid paying gas bills until your tenants freeze." Leaving one's building without heat during Chicago's winters was of a different order from refusing to fix faulty wiring or broken windows. It indicated a new phase in their operation, in which the goal was not to get money from tenants but to force them out altogether. For tenants, the results could be lethal. After her nineteen-month-old son, Scott, died of pneumonia, Mary Miller told reporters: "We had to huddle together around the stove and pile on coats and blankets. But it didn't do any good." Every time she complained, "the landlady would say 'If you don't like it get out.'" In the winter of 1969, three babies died over a three-week period because their West Side slum apartments had gone unheated. Their deaths confirmed the insight of the Chicago Tribune's investigative reporters, who noted that, "when someone has to die in this shabby shell game played for money, it is usually a child."

Slumlords' eagerness to rid their buildings of tenants was part of yet another profit-making scheme. It involved the manipulation of the Illinois Fair Plan, which was established in the aftermath of the 1968 riots to ensure that black neighborhoods were covered by fire insurance. As a result of the Fair Plan, buildings in Lawndale were now insurable for the same amount as those on the city's North Side Gold Coast. Slumlords realized that they could insure their rotting, neglected structures for twenty to thirty times what the buildings were worth. Of course, as one observer noted, they "aren't worth anything unless you burn them"--but if you didn't mind arson, then "even an abandoned building could be turned into a $60,000 windfall."

Al Berland didn't mind. By August 1970, fires had broken out in forty-seven of his buildings and he had collected $350,000 in insurance. In one case, a tenant saved the lives of his four children by dropping them one at a time from a second-floor window. In another, Berland and Wolf were observed entering a property they owned at 715 South Lawndale "carefully" carrying some liquid in a bucket. The two men left "in a hurry" and shortly thereafter the building went up in flames. Later that day the police found Berland at his paint store, still wearing the clothing described by a witness. The witness later withdrew from the case "after his car caught fire mysteriously in front of his home." Chicago police sergeant John Moore, an arson expert, said that in his department Berland was known as "a torch."

March 18, 2013

France, J'ai Peur de Vous

This morning I sent off the following e-mail:

Bonjour la famille d'xxxxx. Comment allez-vous? Je suis Ta-Nehisi Coates. Je crois que je resterai à chez vous pour quatre jours. Je voudrais vous remercier pour votre hospitalité. Mon français n'est pas bien. Mais, j'adore le langue et j'espère l'apprendre. Donc, quelque chose ne le sujet de moi. Je m'appelle Ta-Nehisi. Je suis américain. J'habite à New York avec ma femme Kenyatta et mon fils Samori. (J'envoye un photo de ma famille aussi.) J'ai 37 ans et je suis en écrivain. J'aime leer, regarder le film et courir (faire du jogging.)I'm leaving for Europe on Thursday for nine days--three in Paris and six in Montreux. The first three will be me attempting to apply what I've learned over the last two years. I'll spend the last six in intensive six-hour French classes. The note is to the family I'll be staying with.

Et je pense que c'est toute. Merci beaucoup pour toute le chose. Excusez mon français s'il vous plait. Merci beaucoup.

I am feeling the need to, again, express to you how precisely afraid I am. My passport arrived last Friday and I was -- all at once -- excited and horrified. Let us talk about the horror. For some time now I have been engaged to the theory of français. I've enjoyed playing around with the tenses, using the language with my tutor and butchering the grammar in my notes. I've generally played around with the idea of actually going to Europe. Even after I made travel and study arrangements, it all still seemed like theory.

Somehow I'd held on to the idea that my passport would be lost in the mail, or my application would be rejected on account of my Dad's seditious past. No dice.

There is an image stuck in my head: I board a plane. The plane takes off. A hole in the sky appears. The plane flies through the hole and disappears into some unknown other side that people call "Europe."

What happens over there? Can I jog in the streets? Will people ask if I know Kobe Bryant? If I forget my place and say "tu" instead of "vous" will they cane me? And if I say "vous" instead of "tu" will they think I am being sarcastic? Who goes to another country and stays with people they don't know?

I don't know. I don't know anything. This is truly frightening -- and exhilarating -- part of language study. It's total submission. All around you will be people who know much more than you about everything. And the only way to learn is to accept this. You can't know what's coming next. You can't think about false goals like fluency. You just have to accept your own horribleness, your own ignorance and believe--almost on faith--that someday you will be less horrible and less ignorant.

I've come to the point where I can accept that I am afraid and keep going. This is not courage, so much as understanding there's no other way. People who read this blog now send me notes in French. At speeches Haitian students approach me, and they speak French. My kid is starting to believe that learning a language is cool. I'm hemmed in by all of this, by ma grande bouche.

And now there's no other way. Ces choses doit être fait.

What Chris Hayes Means to the Debate

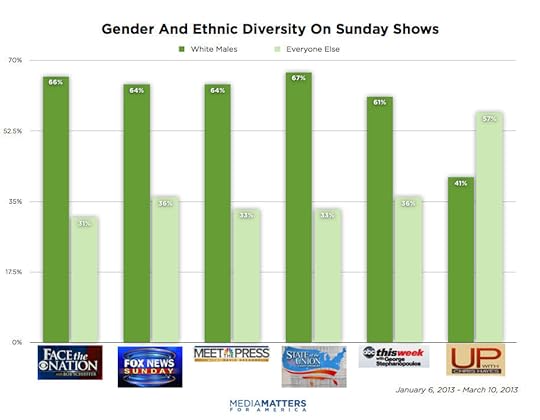

As we congratulate Chris Hayes on his move to primetime, I think it's worth looking at the considerable impact of his show. Courtesy of Alyssa Rosenberg, I think this chart from Media Matters is a really important illustration of Up With Chris Hayes contribution to "The Debate." The comparison here has problems. The other four shows here are rooted in "The Big Get," and are framed around an interview with a senator or a governor, people who generally tend to be white and male. But Chris features politicians in the way that they feature anyone else. If he gets a senator or governor, great. If he doesn't, oh well. From his perspective there's no real reason to believe that John McCain is going to give you the most informed perspective on housing policy.

The implications go beyond merely an amorphous "diversity." I am almost never surprised by anything a politician says on a Sunday talk show -- politicians generally parrot the party line. But I am very often surprised by what I hear on Up With Chris Hayes. That is because the show is more interested in policy itself, than the choreography of politics. You are not going to turn on Chris Hayes and hear "Is Climate Change Real? Ted Cruz and Andrew Cuomo Debate. You Decide." You are going to hear a scientist who actually knows what he's talking about.

I guess it's worth noting that Chris makes no pretense of objectivity. His is clearly a left-wing bias. This means nothing to me. The other Sunday shows are biased towards power. For years it was said that the Left needed a Fox News. I have never believed that. But I do think Fox News could use a Chris Hayes.

March 15, 2013

Western Thought for Class Cutters and Schoolmen Reformed

The Leviathan (Chapter IV: Of Speech)

This was probably my favorite chapter so far, given my chosen craft. I continue to be amazed at Hobbes literalism. He rails against metaphor and insists that words, and the training together of words, have precise meaning. Hobbes is pursuing truth. Words are his tools. Should his words be erroneous, he might find himself as the scientist fumbling with scales out of calibration. (TNC and The Horde are jacking for beats.)

For Hobbes, "truth consisteth in the right ordering of names in our affirmations." I don't want to keep beating the atheist drum, but this strikes me as an expansive vision of man's power. Perhaps the idea that total truth can be captured by words correctly applied was common at the time. I don't know. What's interesting to me also is that art, in no way, figures into Hobbes conception of truth. Poetry--or what today considers poetry--seems also out of the truth business. Here Hobbes list some of the abuses of language, including metaphor among them:

First, when men register their thoughts wrong by the inconstancy of the signification of their words; by which they register for their conceptions that which they never conceived, and so deceive themselves. Secondly, when they use words metaphorically; that is, in other sense than that they are ordained for, and thereby deceive others. Thirdly, when by words they declare that to be their will which is not. Fourthly, when they use them to grieve one another: for seeing nature hath armed living creatures, some with teeth, some with horns, and some with hands, to grieve an enemy, it is but an abuse of speech to grieve him with the tongue, unless it be one whom we are obliged to govern; and then it is not to grieve, but to correct and amend.

I was reminded that Hobbes himself uses metaphor, but he almost always does it with a literalness and precision. I might think "a rounded quadrangle" has meaning--signifying the impossibility of a relationship, for instance. But Hobbes rejects paradox as a literary, or perhaps, philosophical device. Consider this remarkable image:

By this it appears how necessary it is for any man that aspires to true knowledge to examine the definitions of former authors; and either to correct them, where they are negligently set down, or to make them himself. For the errors of definitions multiply themselves, according as the reckoning proceeds, and lead men into absurdities, which at last they see, but cannot avoid, without reckoning anew from the beginning; in which lies the foundation of their errors. From whence it happens that they which trust to books do as they that cast up many little sums into a greater, without considering whether those little sums were rightly cast up or not; and at last finding the error visible, and not mistrusting their first grounds, know not which way to clear themselves, spend time in fluttering over their books; as birds that entering by the chimney, and finding themselves enclosed in a chamber, flutter at the false light of a glass window, for want of wit to consider which way they came in.I let this go on to feature more of Hobbes writing, which is really so sharp here. But note the concrete nature of the image. It is not abstract, and even if you've never seen the thing, you can imagine what Hobbes is saying to you.

So that in the right definition of names lies the first use of speech; which is the acquisition of science: and in wrong, or no definitions, lies the first abuse; from which proceed all false and senseless tenets; which make those men that take their instruction from the authority of books, and not from their own meditation, to be as much below the condition of ignorant men as men endued with true science are above it. For between true science and erroneous doctrines, ignorance is in the middle. Natural sense and imagination are not subject to absurdity. Nature itself cannot err: and as men abound in copiousness of language; so they become more wise, or more mad, than ordinary. Nor is it possible without letters for any man to become either excellently wise or (unless his memory be hurt by disease, or ill constitution of organs) excellently foolish. For words are wise men's counters; they do but reckon by them: but they are the money of fools, that value them by the authority of an Aristotle, a Cicero, or a Thomas, or any other doctor whatsoever, if but a man.

As always, I am amused by his disrespect for the "Schoolmen"--they who traffic in "many words making nothing understood." What is the line from Aristotle to Cicero? I now know why Hobbes hates Aristotle, but I know nothing of Cicero. What was happening at that moment? I feel like I haven't gotten a clear picture from comments as to how much of a break Hobbes was from the past. He certainly feels like he's a break. He writes like an insurgent intellectual, not like someone guarding a hallowed tradition.

Western Thought For Class Cutters And Schoolmen Reformed

The Leviathan (Chapter IV: Of Speech)

This was probably my favorite chapter so far, given my chosen craft. I continue to be amazed at Hobbes literalism. He rails against metaphor and insists that words, and the training together of words, have precise meaning. Hobbes is pursuing truth. Words are his tools. Should his words be erroneous, he might find himself as the scientist fumbling with scales out of calibration. (TNC and The Horde are jacking for beats.)

For Hobbes, "truth consisteth in the right ordering of names in our affirmations." I don't want to keep beating the atheist drum, but this strikes me as an expansive vision of man's power. Perhaps the idea that total truth can be captured by words correctly applied was common at the time. I don't know. What's interesting to me also is that art, in no way, figures into Hobbes conception of truth. Poetry--or what today considers poetry--seems also out of the truth business. Here Hobbes list some of the abuses of language, including metaphor among them:

First, when men register their thoughts wrong by the inconstancy of the signification of their words; by which they register for their conceptions that which they never conceived, and so deceive themselves. Secondly, when they use words metaphorically; that is, in other sense than that they are ordained for, and thereby deceive others. Thirdly, when by words they declare that to be their will which is not. Fourthly, when they use them to grieve one another: for seeing nature hath armed living creatures, some with teeth, some with horns, and some with hands, to grieve an enemy, it is but an abuse of speech to grieve him with the tongue, unless it be one whom we are obliged to govern; and then it is not to grieve, but to correct and amend.

I was reminded that Hobbes himself uses metaphor, but he almost always does it with a literalness and precision. I might think "a rounded quadrangle" has meaning--signifying the impossibility of a relationship, for instance. But Hobbes rejects paradox as a literary, or perhaps, philosophical device. Consider this remarkable image:

By this it appears how necessary it is for any man that aspires to true knowledge to examine the definitions of former authors; and either to correct them, where they are negligently set down, or to make them himself. For the errors of definitions multiply themselves, according as the reckoning proceeds, and lead men into absurdities, which at last they see, but cannot avoid, without reckoning anew from the beginning; in which lies the foundation of their errors. From whence it happens that they which trust to books do as they that cast up many little sums into a greater, without considering whether those little sums were rightly cast up or not; and at last finding the error visible, and not mistrusting their first grounds, know not which way to clear themselves, spend time in fluttering over their books; as birds that entering by the chimney, and finding themselves enclosed in a chamber, flutter at the false light of a glass window, for want of wit to consider which way they came in.I let this go on to feature more of Hobbes writing, which is really so sharp here. But note the concrete nature of the image. It is not abstract, and even if you've never seen the thing, you can imagine what Hobbes is saying to you.

So that in the right definition of names lies the first use of speech; which is the acquisition of science: and in wrong, or no definitions, lies the first abuse; from which proceed all false and senseless tenets; which make those men that take their instruction from the authority of books, and not from their own meditation, to be as much below the condition of ignorant men as men endued with true science are above it. For between true science and erroneous doctrines, ignorance is in the middle. Natural sense and imagination are not subject to absurdity. Nature itself cannot err: and as men abound in copiousness of language; so they become more wise, or more mad, than ordinary. Nor is it possible without letters for any man to become either excellently wise or (unless his memory be hurt by disease, or ill constitution of organs) excellently foolish. For words are wise men's counters; they do but reckon by them: but they are the money of fools, that value them by the authority of an Aristotle, a Cicero, or a Thomas, or any other doctor whatsoever, if but a man.

As always, I am amused by his disrespect for the "Schoolmen"--they who traffic in "many words making nothing understood." What is the line from Aristotle to Cicero? I now know why Hobbes hates Aristotle, but I know nothing of Cicero. What was happening at that moment? I feel like I haven't gotten a clear picture from comments as to how much of a break Hobbes was from the past. He certainly feels like he's a break. He writes like an insurgent intellectual, not like someone guarding a hallowed tradition.

Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog

- Ta-Nehisi Coates's profile

- 17153 followers