Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog, page 25

December 11, 2013

From Centralized Planning to Centralized Killing

Your disenchantment is a threat to our socialist faith.

--E. P. Thompson

Some quick notes on the passages from Postwar which I alluded to in the last post. In terms of the atheist style, a couple of examples should suffice. The first is Judt looking at the impact of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's The Gulag Archipelago on socialist intellectuals of Europe, and particularly Paris:

Communism, it was becoming clear, had defiled and despoiled its radical heritage. And it was continuing to do so, as the genocide in Cambodia and the widely-publicized trauma of the Vietnamese ‘boat people’ would soon reveal.256 Even those in Western Europe—and they were many—who held the United States largely responsible for the disasters in Vietnam and Cambodia, and whose anti-Americanism was further fuelled by the American-engineered killing of Chile’s Salvador Allende just three months before the publication of The Gulag Archipelago, were increasingly reluctant to conclude as they had once done that the Socialist camp had the moral upper hand. American imperialism was indeed bad—but the other side was worse, perhaps far worse.

At this point the traditional ‘progressive’ insistence on treating attacks on Communism as implicit threats to all socially-ameliorative goals—i.e. the claim that Communism, Socialism, Social Democracy, nationalization, central planning and progressive social engineering were part of a common political project—began to work against itself. If Lenin and his heirs had poisoned the well of social justice, the argument ran, we are all damaged. In the light of twentieth-century history the state was beginning to look less like the solution than the problem, and not only or even primarily for economic reasons. What begins with centralized planning ends with centralized killing.

And later on the impact of François Furet's La Révolution Française:

The political implications of Furet’s thesis were momentous, as its author well understood. The failings of Marxism as a politics were one thing, which could always be excused under the category of misfortune or circumstance. But if Marxism were discredited as a Grand Narrative—if neither reason nor necessity were at work in History—then all Stalin’s crimes, all the lives lost and resources wasted in transforming societies under state direction, all the mistakes and failures of the twentieth century’s radical experiments in introducing Utopia by diktat, ceased to be ‘dialectically’ explicable as false moves along a true path. They became instead just what their critics had always said they were: loss, waste, failure and crime. Furet and his younger contemporaries rejected the resort to History that had so coloured intellectual engagement in Europe since the beginning of the 1930s. There is, they insisted, no ‘Master Narrative’ governing the course of human actions, and thus no way to justify public policies or actions that cause real suffering today in the name of speculative benefits tomorrow.

I've allude to this sense in Judt's work before--the idea that there is no "Master Narrative," no ghost in the machinery of the universe, no arc bending toward justice. It is, to me, one of the most arresting aspects of the book. It's not that Judt is amoral or disinterested--his heart is clearly with the Left. But he greets his ostensible allies with ice-water vision. , which is to say he subjects his own ideological roots and his own ideological cousins to withering criticism.

Journalists, writers and thinkers are often hailed for their willingness to engage "the pieties of both the left and the right" or some such. Whenever I see that kind of language my eyes glaze over. A willingness to critique both sides isn't evidence of any particular wisdom--the critique could simply be wrong. (Journalists, in particular, make this mistake with alarming regularity.) False equivalence isn't nuance. And moderation in writing style isn't depth. But there is something to be said for real nuance. For trying one's best to see clearly. This book is not simply offering me more information, it's offering me a method of attempting to get clear.

Everything isn't what it should be. The lack of footnotes is a huge problem. (Sorry Dad. That one hurts.) Still I think Postwar qualifies as a "knock you on your ass" book.

From Centralized Planning To Centralized Killing

Your disenchantment is a threat to our socialist faith.

--E. P. Thompson

Some quick notes on the passages from Postwar which I alluded to in the last post. In terms of the atheist style, a couple of examples should suffice. The first is Judt looking at the impact of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's The Gulag Archipelago on socialist intellectuals of Europe, and particularly Paris:

Communism, it was becoming clear, had defiled and despoiled its radical heritage. And it was continuing to do so, as the genocide in Cambodia and the widely-publicized trauma of the Vietnamese ‘boat people’ would soon reveal.256 Even those in Western Europe—and they were many—who held the United States largely responsible for the disasters in Vietnam and Cambodia, and whose anti-Americanism was further fuelled by the American-engineered killing of Chile’s Salvador Allende just three months before the publication of The Gulag Archipelago, were increasingly reluctant to conclude as they had once done that the Socialist camp had the moral upper hand. American imperialism was indeed bad—but the other side was worse, perhaps far worse.

At this point the traditional ‘progressive’ insistence on treating attacks on Communism as implicit threats to all socially-ameliorative goals—i.e. the claim that Communism, Socialism, Social Democracy, nationalization, central planning and progressive social engineering were part of a common political project—began to work against itself. If Lenin and his heirs had poisoned the well of social justice, the argument ran, we are all damaged. In the light of twentieth-century history the state was beginning to look less like the solution than the problem, and not only or even primarily for economic reasons. What begins with centralized planning ends with centralized killing.

And later on the impact of François Furet's La Révolution Française:

The political implications of Furet’s thesis were momentous, as its author well understood. The failings of Marxism as a politics were one thing, which could always be excused under the category of misfortune or circumstance. But if Marxism were discredited as a Grand Narrative—if neither reason nor necessity were at work in History—then all Stalin’s crimes, all the lives lost and resources wasted in transforming societies under state direction, all the mistakes and failures of the twentieth century’s radical experiments in introducing Utopia by diktat, ceased to be ‘dialectically’ explicable as false moves along a true path. They became instead just what their critics had always said they were: loss, waste, failure and crime. Furet and his younger contemporaries rejected the resort to History that had so coloured intellectual engagement in Europe since the beginning of the 1930s. There is, they insisted, no ‘Master Narrative’ governing the course of human actions, and thus no way to justify public policies or actions that cause real suffering today in the name of speculative benefits tomorrow.

I've allude to this sense in Judt's work before--the idea that there is no "Master Narrative," no ghost in the machinery of the universe, no arc bending toward justice. It is, to me, one of the most arresting aspects of the book. It's not that Judt is amoral or disinterested--his heart is clearly with the Left. But he greets his ostensible allies with ice-water vision. , which is to say he subjects his own ideological roots and his own ideological cousins to withering criticism.

Journalists, writers and thinkers are often hailed for their willingness to engage "the pieties of both the left and the right" or some such. Whenever I see that kind of language my eyes glaze over. A willingness to critique both sides isn't evidence of any particular wisdom--the critique could simply be wrong. (Journalists, in particular, make this mistake with alarming regularity.) False equivalence isn't nuance. And moderation in writing style isn't depth. But there is something to be said for real nuance. For trying one's best to see clearly. This book is not simply offering me more information, it's offering me a method of attempting to get clear.

Everything isn't what it should be. The lack of footnotes is a huge problem. (Sorry Dad. That one hurts.) Still I think Postwar qualifies as a "knock you on your ass" book.

Mandela and the Question of Violence

Juda Ngwenya/Reuters

Juda Ngwenya/ReutersI was right to be wrong, while you and your kind were wrong to be right.

—Pierre Courtade

I have the misfortune of being near the end of Tony Judt's Postwar at a moment when of the great figures of our history, Nelson Mandela, has passed. Judt's gaze is relentless. He rejects all grand narratives, skewers Utopianism (mostly in the form of Communism), and eschews the notion that history has definite shape and form. States are mostly amoral. In one breath he will write admiringly of the Nordic countries. In the next he will detail their descent into eugenics in the mid-20th century.

This is what I mean when I say that Judt has an atheist view of history. God does not care about history, and history does not care about humans. There is no triumphalism, in Postwar, about Western values and democracy. What you see is a continent at war with itself. The upholding of democratic values is a constant struggle, often lost—in the colonies, in the Eastern bloc, in Greece, in Portugal, in Spain. Even among the great Western powers there is the sense that no one is immune to the virus of authoritarianism.

There is great humility in Judt's portrait of Europe, a humility that is largely absent from the portrait of the West foisted upon the darker peoples of the world. Non-African writers love to congratulate Nelson Mandela on not becoming another "Mugabe," as though despotism is something Africans are uniquely tempted toward; as though colonialism was not, itself, a form of kleptocratic despotism. I too am happy that Mandela did not become another Mugabe. I am happier still that he did not become—as far as these analogical games go—another Leopold.

This Western arrogance is as broad as it is insidious. There was a well-reported piece in the Times a few days ago on the disappointment that's followed Mandela's presidency. A similar note has been sounded in seemingly every obit and article concerning Mandela's death. It's not so much that these stories shouldn't be written, it's that they shouldn't treated the subject as though a man were biting a dog. That people are shocked that South Africa, almost 20 years out of apartheid, is struggling with fairness and democracy, reflects a particular ignorance, a particular blindness, and a peculiar lack of humility, about our own struggles.

On the great issue of the day, the generations that followed George Washington offered not just disappointment but betrayal. "The unfortunate condition of the people whose labors I in part employed," Washington wrote, "has been the only unavoidable subject of regret." Americans did not simply tolerate this "unfortunate condition," they turned it into the cornerstone of the American economic system. By 1860, 60 percent of all American exports came from cotton produced by slave labor. "Property in man" was, according to Yale historian David Blight, worth some $3.5 billion more than "all of America's manufacturing, all of the railroads, all of the productive capacity of the United States put together."

In short order, Washington's slaveholding descendants went from evincing skepticism about slavery to calling it "a positive good" and "a great physical, philosophical, and moral truth." And they did this while plundering and raiding this continent's aboriginal population. For at least its first 100 years, or perhaps longer, this country was a disappointment, an experiment which—by its own standards of life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness—failed miserably. America is not unique. It is the product of imperfect humans. As is South Africa. That people turn to the country of Nelson Mandela and wonder why it hasn't magically transformed itself into a perpetual font of milk and honey is a symptom of our blindness to our common humanity.

Nowhere is that blindness more apparent then in the constant, puerile need to critique Mandela's turn toward violence. The impulse is old. "Why Won't Mandela Renounce Violence?" asked a New York Times column in 1990. Is that what we said to Savimbi? To Mobutu?

Malcolm X understood:

If violence is wrong in America, violence is wrong abroad. If it is wrong to be violent defending black women and black children and black babies and black men, then it is wrong for America to draft us, and make us violent abroad in defense of her. And if it is right for America to draft us, and teach us how to be violent in defense of her, then it is right for you and me to do whatever is necessary to defend our own people right here in this country.

Martin Luther King Jr. agreed:

As I have walked among the desperate, rejected and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems ... But, they asked, what about Vietnam? They asked if our own nation wasn't using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today, my own government.

As did Mandela. Offered the chance to be free by the avowed white supremacist P.W. Botha if he would renounce violence, Mandela replied, “Let him renounce violence.” Americans should understand this. Violent resistance to tyranny, violent defense of one's body, is not simply a political strategy in our country, it is taken as a basic human right. Our own revolution was purchased with the blood of 22,000 nascent American dead. Dissenters were tarred and feathered. American independence and American power has never rested on nonviolence, but on the willingness to do great—at times existential—violence.

Perhaps we would argue that Malcolm X, Mandela, and King were wrong, and that states should be immune to ethics of nonviolence. But even our rhetoric toward freedom movements which employ violence is inconsistent. Mandela and the ANC were "terrorists." The Hungarian revolutionaries of 1956, the Northern Alliance opposing the Taliban, the Libyans opposing Gaddafi were "freedom fighters." Thomas Friedman hopes for an "Arab Mandela" one moment, while the next telling those same Arabs to "suck on this." The point here is not that nonviolence is bunk, but that it is is bunk when invoked by those who rule by the gun.

In the shadow of our conversation, one sees a constant, indefatigable specter which has dogged us from birth. For the most of American history, very few of our institutions believed that black people were entitled to the rights of other Americans. Included in this is the right of self-defense. Nonviolence worked because it conceded that right in the pursuit of other rights. But one should never lose sight of the precise reasons why America preaches nonviolence to some people while urging other people to arms.

Jimmy Baldwin knew:

The real reason that nonviolence is considered to be a virtue in Negroes—I am not speaking now of its racial value, another matter altogether—is that white men do not want their lives, their self-image, or their property threatened. One wishes they would say so more often.

The questions which dog us about Mandela's legacy, his relationship to other African autocrats, the great imperfections which remain in his country, and his insistence on the right of self-defense ultimately say more about us than they do about Mandela. "I cannot sell my birthright," Mandela responded to calls for him to renounce violence. "Nor am I prepared to sell the birthright of the people to be free."

This is a universal appeal, and our inability to see such universality in those who are black, or in those who oppose our stated interests, reveal the borders of all our grand talk about democratic values. That is the next frontier. A serious embrace of universality. A rejection of selective morality.

December 8, 2013

Gingrich vs. the Right on Apartheid: 'What Would You Have Done?'

Representative Dick Gephardt, Speaker Newt Gingrich, Nelson Mandela, and Bill Clinton at a 1998 ceremony where Mandela received the Congressional Gold Medal. (Ruth Fremson/Associated Press)

Representative Dick Gephardt, Speaker Newt Gingrich, Nelson Mandela, and Bill Clinton at a 1998 ceremony where Mandela received the Congressional Gold Medal. (Ruth Fremson/Associated Press)I think this is a fairly noteworthy statement from Newt Gingrich on Mandela's passing that should get some airing. Gingrich is addressing the rather disgraceful response to Mandela's passing that we've seen in some quarters:

Some of the people who are most opposed to oppression from Washington attack Mandela when he was opposed to oppression in his own country.

After years of preaching non-violence, using the political system, making his case as a defendant in court, Mandela resorted to violence against a government that was ruthless and violent in its suppression of free speech.As Americans we celebrate the farmers at Lexington and Concord who used force to oppose British tyranny. We praise George Washington for spending eight years in the field fighting the British Army’s dictatorial assault on our freedom.

Patrick Henry said, “Give me liberty or give me death.”

Thomas Jefferson wrote and the Continental Congress adopted that “all men are created equal, and they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Doesn’t this apply to Nelson Mandela and his people?

Some conservatives say, ah, but he was a communist.

Actually Mandela was raised in a Methodist school, was a devout Christian, turned to communism in desperation only after South Africa was taken over by an extraordinarily racist government determined to eliminate all rights for blacks.

I would ask of his critics: where were some of these conservatives as allies against tyranny? Where were the masses of conservatives opposing Apartheid? In a desperate struggle against an overpowering government, you accept the allies you have just as Washington was grateful for a French monarchy helping him defeat the British.

I think it's important to note that Gingrich's position here is not particularly new. This is not an attempt to rewrite history, or claim someone in death whom Gingrich opposed in life. Newt Gingrich was among a cadre of conservatives who opposed the mainstream conservative stance on apartheid and ultimately helped override Reagan's unconscionable veto of sanctions. At the time, Gingrich was allied with a group of young conservatives including Vin Weber looking to challenge Republican orthodoxy on South Africa. "South Africa has been able to depend on conservatives to treat them with benign neglect," said Weber. "We served notice that, with the emerging generation of conservative leadership, that is not going to be the case."

Something else: There's a video attached to the post in which Gingrich gives his thoughts on Mandela's passing. When Gingrich compliments Mandela on his presidency he doesn't do so within the context of alleged African pathologies, but within the context of countries throughout the world. It's a textbook lessons in "How not to be racist," which is to say it is a textbook lesson in how to talk about Nelson Mandela as though he were a human being.

More soon.

Newt Gingrich To Conservatives: 'What Would You Have Done?'

I think this is a fairly noteworthy statement from Newt Gingrich on Mandela's passing that should get some airing. Gingrich is addressing the rather disgraceful response to Mandela's passing that we've seen in some quarters:

Some of the people who are most opposed to oppression from Washington attack Mandela when he was opposed to oppression in his own country.

After years of preaching non-violence, using the political system, making his case as a defendant in court, Mandela resorted to violence against a government that was ruthless and violent in its suppression of free speech.As Americans we celebrate the farmers at Lexington and Concord who used force to oppose British tyranny. We praise George Washington for spending eight years in the field fighting the British Army’s dictatorial assault on our freedom.

Patrick Henry said, “Give me liberty or give me death.”

Thomas Jefferson wrote and the Continental Congress adopted that “all men are created equal, and they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Doesn’t this apply to Nelson Mandela and his people?

Some conservatives say, ah, but he was a communist.

Actually Mandela was raised in a Methodist school, was a devout Christian, turned to communism in desperation only after South Africa was taken over by an extraordinarily racist government determined to eliminate all rights for blacks.

I would ask of his critics: where were some of these conservatives as allies against tyranny? Where were the masses of conservatives opposing Apartheid? In a desperate struggle against an overpowering government, you accept the allies you have just as Washington was grateful for a French monarchy helping him defeat the British.

I think it's important to note that Gingrich's position here is not particularly new. This is not an attempt to rewrite history, or claim someone in death whom Gingrich opposed in life. Newt Gingrich was among a cadre of conservatives who opposed the mainstream conservative stance on Apartheid and ultimately helped override Reagan's unconscionable veto of sanctions. At the time, Gingrich was allied with a group of young conservatives including Vin Weber looking to challenge Republican orthodoxy on South Africa. "South Africa has been able to depend on conservatives to treat them with benign neglect," said Weber. "We served notice that, with the emerging generation of conservative leadership, that is not going to be the case."

Something else: There's a video attached to the post in which Gingrich gives his thoughts on Mandela's passing. When Gingrich compliments Mandela on his presidency he doesn't do so within the context of alleged African pathologies, but within the context of countries throughout the world. It's a textbook lessons in "How not to be racist," which is to say it is a textbook lesson in how to talk about Nelson Mandela as though he were a human being.

More soon.

December 6, 2013

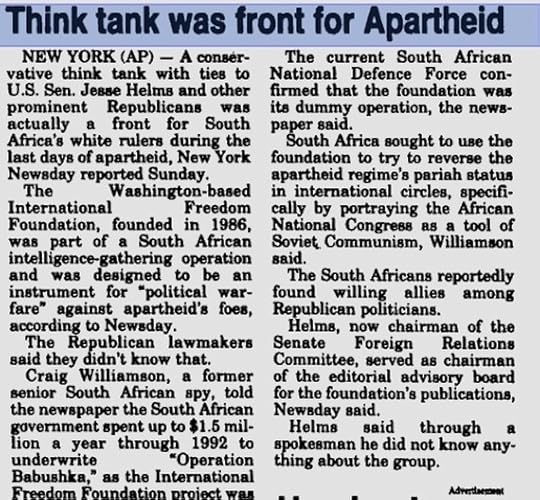

Apartheid's Useful Idiots

Gettysburg Times, July 17, 1995

Gettysburg Times, July 17, 1995Nelson Mandela died yesterday, and all around the world, much-deserved hosannas are coming in, praising the life of one of the most important figures in modern Western history. That last bit reflects my own bias. What's become clear in all my studies of our history of World War II, of the Civil War, of Tocqueville, of Rousseau, of Zionism, of black nationalism, is that understanding Enlightenment ideals requires understanding those places where ideals and humanity meet. If you call yourself a lover of democracy, but have not studied the black diaspora, your deeds mock your claims. Understanding requires more than sloganeering, and parroting—it requires confronting our failures.

For many years, a large swath of this country failed Nelson Mandela, failed its own alleged morality, and failed the majority of people living in South Africa. We have some experience with this. Still, it's easy to forget William F. Buckley—intellectual founder of the modern right—effectively worked as a press agent for apartheid:

Buckley was actively courted by Chiang Kai-Shek's Taiwan, Franco's Spain, South Africa, Rhodesia and Portugal's African colonies, and went on expenses-paid trips trips to some of these countries.

When he returned from Mozambique in 1962, Buckley wrote a column describing the backwardness of the African population over which Portugal ruled, "The more serene element in Africa tends to believe that rampant African nationalism is self-discrediting, and that therefore the time is bound to come when America, and the West ... will depart from our dogmatic anti-Colonialism and realize what is the nature of the beast."

In the fall of 1962, during a visit to South Africa, arranged by the Information Ministry, Buckley wrote that South African apartheid "has evolved into a serious program designed to cope with a melodramatic dilemma on whose solution hangs, quite literally, the question of life or death for the white man in South Africa."

Buckley's racket as an American paid propagandist for white supremacy would be repeated over the years in conservative circles. As Sam Kleiner demonstrates in Foreign Policy, apartheid would ultimately draw some of America's most celebrated conservatives into its orbit. The roster includes Grover Norquist, Jack Abramoff, Jesse Helms, and Senator Jeff Flake. Jerry Falwell denounced Desmond Tutu as a "phony" and led a "reinvestment" campaign during the 1980s. At the late hour of 1993, Pat Robertson opined, "I know we don't like apartheid, but the blacks in South Africa, in Soweto, don't have it all that bad."

Not all prominent conservatives were so dishonorable. When Congress overrode President Ronald Reagan's veto of sanctions of South Africa, Mitch McConnell, for instance, was forthright—"I think he is wrong ... We have waited long enough for him to come on board." When Falwell embarrassed himself by condemning Tutu, some Republican senators denounced him.

But the overall failure of American conservatives to forthrightly deal with South Africa's white-supremacist regime, coming so soon after their failure to deal with the white-supremacist regime in their own country, is part of their heritage, and thus part of our heritage. When you see a Tea Party protestor waving the flag of slavery in front of the home of the first black president, understand that this instinct has been cultivated. It is still, at this very hour, being cultivated:

He won the country's first free presidential elections in 1994 and worked to unite a scarred and anxious nation. He opened up the economy to the world, and a black middle class came to life. After a single term, he voluntarily left power at the height of his popularity. Most African rulers didn't do that, but Mandela said, "I don't want a country like ours to be led by an octogenarian. I must step down while there are one or two people who admire me."

That is the Wall Street Journal, offering a shameful, condescending "tribute" to one of the great figures of our time. Understand the racism here. It is certainly true that "most African rulers" do not willingly hand over power. That is because most human leaders do not hand over power. What racism does is take a basic human tendency and make it it the property of ancestry. As though Franco never happened. As though Hitler and Stalin never happened. As though Pinochet never happened. As though we did not prop up Mobutu. As though South Carolina was not, for most of its history, ruled by Big Men as nefarious and vicious as any "African ruler."

To not see this requires a special disposition, a special blindness, a special shamelessness, a special idiocy.

December 3, 2013

The Invincible Jessie Ware

One of the cool things about teaching is that you're always around young people, who actually have the time to dig through new music and tell you what's good and what's crap. I don't have the time to dig through music like I used to. Moreover, it's gratifying to know that, though I'm 38, I'm not actually aging out of music. At least not yet.

My son keeps playing the new Drake around the crib. I think I might actually like it. One of my kids in my "Voice and Meaning" class put me on to How To Dress Well. They are in heavy rotation right not. A friend of mine who is not my son, and who is not in my class, put me on to Jessie Ware. She still qualifies as a kid, though. Basically anyone not having to cope with the moods of a 13-year old boy is, in my eyes, a kid. Just putting that out there.

Anyway, this Devotion joint is my new hotness. Yes, music nerd-boy, I know that I'm a year late and no one says "new hotness" anymore. Sit down and listen to your elders. And listen to Jessie Ware. This a woman who knows something about missing people, about being marooned in other cities, far from family, and far from home.

As an aside, I was talking about this Jessie Ware song in class the other day. Ware basically repeats the line "Who says 'No' to love?" making subtle changes each time. I was trying to explain how musicians pick out phrases and repeat them, adding new twists each time, and how that evokes emotion and movement. My point is that great writers often do the same thing. Is there a name for this? Is there a more concise way I can explain this? Writing is the only art I've actually studied, I'm approaching my limits.

Bigotry and the English Language

George Lincoln Rockwell (center) attending Nation of Islam rally in 1961. Photo credit: Eve Arnold

George Lincoln Rockwell (center) attending Nation of Islam rally in 1961. Photo credit: Eve ArnoldWes Alwan reaches for the dictionary in his effort to defend Alec Baldwin against the charge of being a bigot:

The problem with these responses is that they redefine “bigot” away from its well-established common usage. In fact, the primary function of a word like “bigot” is to very precisely exclude more conflicted, doubtful states of mind, as in: a bigot is “a person who is obstinately or intolerantly devoted to his or her own opinions and prejudices; especially: one who regards or treats the members of a group (as a racial or ethnic group) with hatred and intolerance” (Merriam-Webster). The obstinate devotion to certain avowed, intolerant beliefs is critical to the way that “bigot” traditionally has been used. The word has its origins in the general notion of close-mindedness: the idea is that a bigot is someone who is un-persuadable, who cannot be argued out of their beliefs. But accusing someone of being close-minded and un-persuadable requires that they adamantly hold the beliefs in question in the first place: it cannot be the case that they’re conflicted or akratic – that for example they sincerely favor gay rights as a matter of principle yet betray this principle during bouts of homophobic rage. Having unsavory impulses and poor impulse control is simply not the same thing as being closed minded and systematically intolerant. To extend the word “bigot” to someone like Baldwin is just to pervert it in order for the sake of exploiting its toxicity to his reputation.

The notion that bigot has "its origins in the general notion of close-mindedness" would be news to etymologists. The origins of the word "bigot" are unknown, but the current theory holds that it is an import from Middle French denoting someone who was sanctimonious or hypocritically religious. Alwan is concerned about the word bigot becoming "perverted," to exploit "its toxicity." But this happened long before Alec Baldwin. As late as the 1700s, the word was brought to English with its French meaning. That it was perverted into other meanings is unremarkable. Language does not exist encased in glass and formaldehyde. And the perversion of words is not a cosmic felony, it is how language actually works.

The word "bigot" has been perverted into many related, similar, meanings. One meaning is Alwan's. Here is another:

a person who strongly and unfairly dislikes other people, ideas, etc. : a bigoted person; especially : a person who hates or refuses to accept the members of a particular group (such as a racial or religious group)."

One who is strongly partial to one's own group, religion, race, or politics and is intolerant of those who differ.

Another definition holds that bigot is "a person who is bigoted" as in "intolerance toward those who hold different opinions from oneself."

My argument is simple: I hold that if you attempt to intimidate and threaten a man by calling him "a little girl" who "probably got raped by a priest," and then you call a gay man a "queen" and threaten to rape him, and justify this by claiming your threat "had absolutely nothing to do with issues of anyone's sexual orientation," and then you threaten someone else by calling them a "cock-sucking fag" and you attempt to excuse yourself by claiming you didn't know "cock-sucking" was a slur and that you didn't say "fag," and you blame your subsequent misfortune on "the fundamentalist wing of gay advocacy, that you are very likely a person who strongly and unfairly dislikes other people; that you are someone who is refusing to accept another group of people as humans; that you are strongly partial to your own group; that you are a bigot.

Bigots come in all shapes and forms. Strom Thurmond tried to raise an entire political party on the basis of segregation, daring the federal government to intervene in the South's domestic affairs."There's not enough troops in the army, " charged Thurmond. "To force the southern people to break down segregation and admit the nigger race into our theatres into our swimming pools into our homes and into our churches."

But Thurmond was not without conflict. He had a black daughter whom he gave financial support, sired the career of black conservative Armstrong Williams, supported Historically Black Colleges and Universities. And Thurmond was not "unpersuadable." He later voted for the Voting Rights Bill, the Martin Luther King holiday, and in the 70s, became first Southern Senator to hire a black staffer. This a man who once claimed that segregation, left "our niggers...better off than most anybody's niggers."

Thurmond's racist views were defended by Senator Trent Lott, who argued that had his hero prevailed, "we wouldn't have had all these problems over the years." Later reporting discovered that this wa the second time Lott had made this comment. As a young man interested in politics, Lott worked for segregationist politicians, eschewing more moderate candidates. As a politician in his own right he frequently addressed the racist White Citizens Council. Lott's endorsements of segregation, some of which were louder than others, spanned some forty years. But as the fight over his more recentendorsement of Thurmond caught fire Lott came out in support of Affirmative Action.

George Rockwell was a virulent racist, and a commander of the American Nazi Party. His embrace of White Power was total, and yet he was a fan of the Nation of Islam and praised them for having...

Was Rockwell without conflict? Was he a bigot? Who qualifies as "unpersuadable?" Do the former slaveholders who, having lost the Civil war, claimed that they'd never defended slavery make the cut? What of the neighbors of Jews who smiled at them one moment, and then looted their homes and turned them over to Nazis the next? And what are we to say of the promoters of "conversion therapy" who claim to "love the sinner" even as they deprive him of the right of family? Are they unconflicted? Are they unpersuadable?gathered millions of the dirty, immoral, drunken, filthy-mouthed, lazy and repulsive people sneeringly called ‘niggers’ and inspired them to the point where they are clean, sober, honest, hard working, dignified, dedicated and admirable human beings in spite of their color.

Alwan's definition of a bigot, as a "global" label encompassing their humanity, as someone who is wholly unpersuadable, wholly without conflict, and wholly without doubt, is not a description of humans, it is a description of myth. And it a definition to which those who live under the power of actual bigots enjoy no access.

Alwan is unhappy that I am raising this point:

I worried, when I published a long post defending Alec Baldwin against charges of bigotry for calling someone a “cocksucking fag,” that I ran the risk of being seen as defending the indefensible. I knew that if the post got any attention, readers who are unfamiliar with my reputation as a (hardcore) liberal might interpret it as a particularly sophisticated piece of crypto-conservatism or closeted bigotry. And I also worried that friends who know me better might wonder how it is I could possibly make such a defense: my motives would be suspect. Indeed, the point of Coates’ marking a portion of my argument as “bizarre,” “terrible,” and “telling” is to signal – without openly calling me a bigot, a ploy that would be too embarrassingly obvious – the fact that my motives are in question: I’m a white guy defending another white guy, not someone making a principled argument (no matter how wrongheaded) about what I believe to be right. I am, possibly, a closeted bigot, dressing up my bigotry in a sophisticated argument; not, as I intend to be, a self-critiquing liberal who wishes to hold liberals – for the sake of consistency, intellectual honesty, and fairness – to their own liberal principles.

If I thought Alwan were a bigot, I would call him one and then make the argument. I am not questioning his motives. I am questioning his knowledge of the world. I am happy to read that he is "self-critiquing liberal." Hopefully he will take the following critique in that spirit: Wes Alwan's understanding of the word "bigot," is ignorant of the word's origins, history and its current usage, especially its usage by those most affected by bigotry. This ignorance is a luxury afforded him by identity. People who live in the thrall of actual racists, and actual homophobes, can't employ Alwan's definition because it would not accurately describe anyone they have ever met.

Very few white people in the 19th century—indeed very few slave-holders—were without conflict and without doubt when considering black people. Many of them were persuadable and akratic. (A great word, by the way.) Some manumitted the enslaved. Others taught them to read, even though it was against the law. Others bore children by them, and sometimes even loved those children. And others still argued that white people should be enslaved too. These people were conflicted, complicated and bigoted. I suspect that the same is true for many homophobic "love the sinner, hate the sin" bigots today.

Perhaps we are now entering a new age wherein we will do violence to our language and Osama Bin Laden will no longer be a terrorist, but "a person who enjoyed a career killing innocent people." Rush Limbaugh will not be a racist, but "a man who has made a career saying racist things." Nathan Bedford Forrest will not have been a white supremacist but "someone who seemed to believe that things would be better if white people held most of the power in our society." Louis Farrakhan will not be an anti-Semite but "someone who exhibits a pattern of making comments against people who identify themselves as Jewish."

I am doubtful that such an age is dawning. In the meantime, I hope a self-identified "self-critiquing liberal" like Alwan--and I mean this--will see that while some people reach for labels simply to conduct a mythical witch-hunt, others reach for labels because in their world witches are very real, and are not the hunted, but the hunters. We will see whether being labeled a "bigot" is ultimately toxic to Alec Baldwin's job prospects. There is no such need to wait on the toxicity of being labeled a "cock-sucking faggot."

Bigotry And The Human Language

George Lincoln Rockwell (center) attending Nation of Islam rally in 1961. Photo credit: Eve Arnold

George Lincoln Rockwell (center) attending Nation of Islam rally in 1961. Photo credit: Eve ArnoldWes Alwan reaches for the dictionary in his effort to defend Alec Baldwin against the charge of being a bigot:

The problem with these responses is that they redefine “bigot” away from its well-established common usage. In fact, the primary function of a word like “bigot” is to very precisely exclude more conflicted, doubtful states of mind, as in: a bigot is “a person who is obstinately or intolerantly devoted to his or her own opinions and prejudices; especially: one who regards or treats the members of a group (as a racial or ethnic group) with hatred and intolerance” (Merriam-Webster). The obstinate devotion to certain avowed, intolerant beliefs is critical to the way that “bigot” traditionally has been used. The word has its origins in the general notion of close-mindedness: the idea is that a bigot is someone who is un-persuadable, who cannot be argued out of their beliefs. But accusing someone of being close-minded and un-persuadable requires that they adamantly hold the beliefs in question in the first place: it cannot be the case that they’re conflicted or akratic – that for example they sincerely favor gay rights as a matter of principle yet betray this principle during bouts of homophobic rage. Having unsavory impulses and poor impulse control is simply not the same thing as being closed minded and systematically intolerant. To extend the word “bigot” to someone like Baldwin is just to pervert it in order for the sake of exploiting its toxicity to his reputation.

The notion that bigot has "its origins in the general notion of close-mindedness" would be news to etymologists. The origins of the word "bigot" are unknown, but the current theory holds that it is an import from Middle French denoting someone who was sanctimonious or hypocritically religious. Alwan is concerned about the word bigot becoming "perverted," to exploit "its toxicity." But this happened long before Alec Baldwin. As late as the 1700s, the word was brought to English with its French meaning. That it was perverted into other meanings is unremarkable. Language does not exist encased in glass and formaldehyde. And the perversion of words is not a cosmic felony, it is how language actually works.

The word "bigot" has been perverted into many related, similar, meanings. One meaning is Alwan's. Here is another:

a person who strongly and unfairly dislikes other people, ideas, etc. : a bigoted person; especially : a person who hates or refuses to accept the members of a particular group (such as a racial or religious group)."

One who is strongly partial to one's own group, religion, race, or politics and is intolerant of those who differ.

Another definition holds that bigot is "a person who is bigoted" as in "intolerance toward those who hold different opinions from oneself."

My argument is simple: I hold that if you attempt to intimidate and threaten a man by calling him "a little girl" who "probably got raped by a priest," and then you call a gay man a "queen" and threaten to rape him, and justify this by claiming your threat "had absolutely nothing to do with issues of anyone's sexual orientation," and then you threaten someone else by calling them a "cock-sucking fag" and you attempt to excuse yourself by claiming you didn't know "cock-sucking" was a slur and that you didn't say "fag," and you blame your subsequent misfortune on "the fundamentalist wing of gay advocacy, that you are very likely a person who strongly and unfairly dislikes other people; that you are someone who is refusing to accept another group of people as humans; that you are strongly partial to your own group; that you are a bigot.

Bigots come in all shapes and forms. Strom Thurmond tried to raise an entire political party on the basis of segregation, daring the federal government to intervene in the South's domestic affairs."There's not enough troops in the army, " charged Thurmond. "To force the southern people to break down segregation and admit the nigger race into our theatres into our swimming pools into our homes and into our churches."

But Thurmond was not without conflict. He had a black daughter whom he gave financial support, sired the career of black conservative Armstrong Williams, supported Historically Black Colleges and Universities. And Thurmond was not "unpersuadable." He later voted for the Voting Rights Bill, the Martin Luther King holiday, and in the 70s, became first Southern Senator to hire a black staffer. This a man who once claimed that segregation, left "our niggers...better off than most anybody's niggers."

Thurmond's racist views were defended by Senator Trent Lott, who argued that had his hero prevailed, "we wouldn't have had all these problems over the years." Later reporting discovered that this wa the second time Lott had made this comment. As a young man interested in politics, Lott worked for segregationist politicians, eschewing more moderate candidates. As a politician in his own right he frequently addressed the racist White Citizens Council. Lott's endorsements of segregation, some of which were louder than others, spanned some forty years. But as the fight over his more recentendorsement of Thurmond caught fire Lott came out in support of Affirmative Action.

George Rockwell was a virulent racist, and a commander of the American Nazi Party. His embrace of White Power was total, and yet he was a fan of the Nation of Islam and praised them for having...

Was Rockwell without conflict? Was he a bigot? Who qualifies as "unpersuadable?" Do the former slaveholders who, having lost the Civil war, claimed that they'd never defended slavery make the cut? What of the neighbors of Jews who smiled at them one moment, and then looted their homes and turned them over to Nazis the next? And what are we to say of the promoters of "conversion therapy" who claim to "love the sinner" even as they deprive him of the right of family? Are they unconflicted? Are they unpersuadable?gathered millions of the dirty, immoral, drunken, filthy-mouthed, lazy and repulsive people sneeringly called ‘niggers’ and inspired them to the point where they are clean, sober, honest, hard working, dignified, dedicated and admirable human beings in spite of their color.

Alwan's definition of a bigot, as a "global" label encompassing their humanity, as someone who is wholly unpersuadable, wholly without conflict, and wholly without doubt, is not a description of humans, it is a description of myth. And it a definition to which those who live under the power of actual bigots enjoy no access.

Alwan is unhappy that I am raising this point:

I worried, when I published a long post defending Alec Baldwin against charges of bigotry for calling someone a “cocksucking fag,” that I ran the risk of being seen as defending the indefensible. I knew that if the post got any attention, readers who are unfamiliar with my reputation as a (hardcore) liberal might interpret it as a particularly sophisticated piece of crypto-conservatism or closeted bigotry. And I also worried that friends who know me better might wonder how it is I could possibly make such a defense: my motives would be suspect. Indeed, the point of Coates’ marking a portion of my argument as “bizarre,” “terrible,” and “telling” is to signal – without openly calling me a bigot, a ploy that would be too embarrassingly obvious – the fact that my motives are in question: I’m a white guy defending another white guy, not someone making a principled argument (no matter how wrongheaded) about what I believe to be right. I am, possibly, a closeted bigot, dressing up my bigotry in a sophisticated argument; not, as I intend to be, a self-critiquing liberal who wishes to hold liberals – for the sake of consistency, intellectual honesty, and fairness – to their own liberal principles.

If I thought Alwan were a bigot, I would call him one and then make the argument. I am not questioning his motives. I am questioning his knowledge of the world. I am happy to read that he is "self-critiquing liberal." Hopefully he will take the following critique in that spirit: Wes Alwan's understanding of the word "bigot," is ignorant of the word's origins, history and its current usage, especially its usage by those most affected by bigotry. This ignorance is a luxury afforded him by identity. People who live in the thrall of actual racists, and actual homophobes, can't employ Alwan's definition because it would not accurately describe anyone they have ever met.

Very few white people in the 19th century—indeed very few slave-holders—were without conflict and without doubt when considering black people. Many of them were persuadable and akratic. (A great word, by the way.) Some manumitted the enslaved. Others taught them to read, even though it was against the law. Others bore children by them, and sometimes even loved those children. And others still argued that white people should be enslaved too. These people were conflicted, complicated and bigoted. I suspect that the same is true for many homophobic "love the sinner, hate the sin" bigots today.

Perhaps we are now entering a new age wherein we will do violence to our language and Osama Bin Laden will no longer be a terrorist, but "a person who enjoyed a career killing innocent people." Rush Limbaugh will not be a racist, but "a man who has made a career saying racist things." Nathan Bedford Forrest will not have been a white supremacist but "someone who seemed to believe that things would be better if white people held most of the power in our society." Louis Farrakhan will not be an anti-Semite but "someone who exhibits a pattern of making comments against people who identify themselves as Jewish."

I am doubtful that such an age is dawning. In the meantime, I hope a self-identified "self-critiquing liberal" like Alwan--and I mean this--will see that while some people reach for labels simply to conduct a mythical witch-hunt, others reach for labels because in their world witches are very real, and are not the hunted, but the hunters. We will see whether being labeled a "bigot" is ultimately toxic to Alec Baldwin's job prospects. There is no such need to wait on the toxicity of being labeled a "cock-sucking faggot."

November 27, 2013

Yeah, Alec Baldwin Really Is a Bigot

Reuters

ReutersResponding to Andrew Sullivan's argument, and my own, that Alec Baldwin is—in fact—kind of a bigot, Wes Alwan offers the following defense:

For calling a photographer a “cocksucking fag” in a blowup caught on video, and another journalist a “fucking little bitch” and “toxic queen” on twitter, Baldwin has been roundly condemned as a “bigot” and “homophobe,” despite the fact that he has been a vocal supporter of gay rights. ...

These condemnations are grounded in a number of highly implausible theses that amount to a very flimsy moral psychology. The first is the extremely inhumane idea that we ought to make global judgments about people’s characters based on their worst moments, when they are least in control of themselves: that what people do or say when they’re most angry or incited reveals a kind of essential truth about them. The second is that we are to condemn human beings merely for having certain impulses, regardless of their behaviors and beliefs. The third is that people’s darkest and most irrational thoughts and feelings trump their considered beliefs: Baldwin can’t possibly really believe in gay rights, according to Coates, if he has any negative feelings about homosexuality whatsoever. The fourth, implied premise here – one that comes out in the comical comments section following Coates’ post – is that we are to take no account whatsoever of the possibility of psychological conflict. We refuse to allow ourselves to imagine that a single human being might have a whole host of conflicted thoughts and feelings about homosexuality: that they might be both attracted to it and repelled by it....

It is just as ludicrous to condemn people for being afraid of or repulsed by homosexuality as it is to condemn them for having violent impulses. Freud thought that homophobia and same sex attraction (which is not the same thing as homosexuality per se) were universal and mutually implicating (a man, for instance, might be both repelled by and fascinated by homosexuality because he associates it with the both terrifying and thrilling prospect of submitting and being penetrated). Whether or not you like such associations or agree with Freud, you cannot condemn people merely for being afraid of something, or for having certain feelings or associations: what counts are their considered thoughts and behaviors. The bigot who gets on TV to tell you that homosexuality ought to be against the law does not belong in the same category as a vocal advocate of gay rights who has not purified himself entirely of negative feelings about homosexuality. Homophobic feelings are no more of a choice than homosexuality itself...

Before I offer a rebuttal, I think it's important that we take an account of the evidence.Two years ago, Baldwin—hounded by paparazzi—Baldwin reacted as follows

It seems Alec finally had enough ... This time, Alec -- clutching a pink stuffed animal -- approached one of the photogs who was hanging out in front of his apartment building and lashed out, "I want you to shut the f**k up ... leave my neighbor alone ... get outta here."

At one point, at the beginning of the confrontation, It sounds like Alec says to the photog, "I know you got raped by a priest or something."

Then, in an effort to assert his dominance, Alec got right in the pap's face ... and in a menacing tone said, "You little girl."

You should watch the video in the hyperlink to get the full effect of this.

A few months ago, offended by something a reporter—who is gay—had written, Baldwin said the following:

George Stark, you lying little bitch. I am gonna fuck you up … I want all of my followers and beyond to straighten out this fucking little bitch, George Stark. @MailOnline … My wife and I attend a funeral to pay our respects to an old friend, and some toxic Brit writes this fucking trash … If put my foot up your fucking ass, George Stark, but I’m sure you’d dig it too much … I’m gonna find you, George Stark, you toxic little queen, and I’m gonna fuck….you….up.

Then two weeks ago Baldwin, again hounded by paparazzi, pursued the cameraman and once they'd back off called one a "cock-sucking fag." Baldwin claimed that he'd actually said "cock-sucking fathead." He also added that he was unaware that "cock-sucker" was a derogatory term for gay men.

Yesterday, it came out that Alec Baldwin will no longer have a show on MSNBC. Baldwin offered the following commentary on his cancellation:

But you've got the fundamentalist wing of gay advocacy—Rich Ferraro and Andrew Sullivan—they're out there, they've got you. Rich Ferraro, this is probably one of his greatest triumphs. They killed my show.

Baldwin didn't blame his own repeated use of anti-gay—dare I say bigoted—slurs. He blamed "the fundamentalist wing of gay advocacy."

My way of understanding this is simple. If I were to be found to, in anger, repeatedly employ anti-Hispanic slurs, to refer to my enemies as "wetbacks" or "illegals," if I were found to address an actual Latino journalist with the term and threaten to say "kick his ass back across the border," and then having lost my job here at The Atlantic blame "the fundamentalist wing of La Raza," I think you would be justified in calling me a bigot. I don't think my support for, say, the DREAM Act, or my horror at Arizona's immigration laws

1

Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog

- Ta-Nehisi Coates's profile

- 17146 followers