Dave Ramsden's Blog, page 2

December 23, 2006

Return of the Magi

Christmas is here and once again I make my annual pilgrimmage to the works of T.S. Eliot to seek out The Journey of the Magi. I notice that last year I stated that I was beginning to understand it. This year I know more, but am less certain that I have any real understanding.

A quick search of Wikipedia reveals "The poem is, instead of a celebration of the wonders of the journey, largely a complaint about a journey that was painful, tedious, and seemingly pointless...The magus seems generally unimpressed by the infant, and yet he realizes that the incarnation has changed everything...The birth of the Christ was the death of his world of magic, astrology, and paganism. The speaker, recalling his journey in old age, says that after that birth his world had died, and he had little left to do but wait for his own end...His narrator in this poem is a witness to historical change who seeks to rise above his historical moment, a man who, despite material wealth and prestige, has lost his spiritual bearings."

All perfectly reasonable, but lacking something. The great rennaissance Magi, such as Ficino, Mirandola and Agrippa, saw the biblical Magi as symbolic of a proper place for Natural magic & astrology within acceptable Christian doctrine. The three sage's wisdom brought them to seek out and pay tribute to the Christ child, thus legitimizing their practices in the proper context. Nevertheless, this was a dangerous path in the eyes of the church, and those who walked upon it often faced the perils of human judgement. One only need reference the trial and execution of Giordano Bruno to understand the stakes at hand. And yet, the tradition persisted in the esoteric underworld, through the Rosicrucian furor and beyond, through the ultimate divorce of magic and science and into the uncertain vogue of the 19th century theosophists and occultists, as well as today's new age mysticism.

If the Wiki's analysis is lacking something, it is the framing of Eliot's poem within the magical mystery tradition which he and his writing seems to explore. He was not alone in this regard. Charles Williams and his fellow Inklings & associates, each in varied but thematically connected ways, managed to reflect the possibilities of a Christian magical theology, hidden from the profane, but once known, forever changing the way one views this world. There is a hint of this in Eliot's Journey, like a watery reflection of the night sky, with one bright star in the west winking through the ripples. Intentional? I'll leave it to the reader to decide.

T. S. Eliot. The Journey of The Magi:

A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.'

And the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory,

Lying down in the melting snow.

There were times we regretted

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces,

And the silken girls bringing sherbet.

Then the camel men cursing and grumbling

And running away, and wanting their liquor and women,

And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters,

And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly

And the villages dirty and charging high prices:

A hard time we had of it.

At the end we preferred to travel all night,

Sleeping in snatches,

With the voices singing in our ears, saying

That this was all folly.

Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley,

Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation;

With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness,

And three trees on the low sky,

And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow.

Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel,

Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver,

And feet kicking the empty wine-skins.

But there was no information, and so we continued

And arrived at evening, not a moment too soon

Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

Now after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, behold, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem, saying, "Where is He who has been born King of the Jews? For we have seen His star in the East and have come to worship Him..." The star which they had seen in the East went before them, till it came and stood over where the young Child was.

[Matthew 2:1–10]

Published on December 23, 2006 20:42

August 1, 2006

Possession

I began this essay and am not sure that I am done with it, even with my own thoughts on its point. I'll post it anyway, though, in the hope that another's thoughts may render me more eloquent...

In 1983 Paul Hewson, better known as Bono, coined the lyric “And the battle's just begun, to claim the victory Jesus won”. It was a line intended to shame both the Protestant and Catholic sides of the religious struggle in Northern Ireland, through its simplicity and its truth. In its naked, common-sense approach, however, the line also extends past its Christian context and symbolizes the crux of so many of the world’s religious conflicts: Possession.

There is something magic about ownership. It is a primal urge, born out of the fear of loss, and ultimately of the potentially tenuous nature of survival. If we do not obtain food, clothing, or shelter we will perish. How much more pressing is the drive to hold the key to eternal life, to extend one’s existence and lessen the fear of the great unknown?

On a physical level, the things we must produce for survival in this world have been translated into the language of commerce. Money is no more than a symbol of work, or of possessions. It is the great middleman which separates our physical toil from the fruit of our labors, allowing us to instead reap whatever reward we desire. It is an enabler, a middle-man, and, like the internet today, an accelerator of anonymity. If I hold money, who is to question how I made it? Did I work hard? Do I deserve its weight in the luxuries of trade? No proper merchant would question it.

In the Western Judeo-Christian tradition, money is really the loophole to the biblical curse: to atone for his sins Adam must work the land all his days, but not if he invests well or wins the lottery. In the undercurrent of logic here we begin to comprehend how some could see the dark attraction of a life of piracy on the high seas. Without God or country, and with money in your pocket, the yoke is broken.

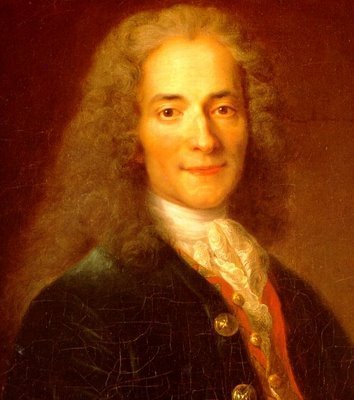

It is, to some extent, this logic which Voltaire put into play in his examination of English religious tolerance in the reformation. Expounding on the subject in his Philosophical letters on the English, Voltaire points out the fact that the English do not embrace each other’s differing sects, but they do have a more developed economic system which justifies tolerance. While France still tried to recover from centuries of bitter religious warfare between its own populace, the English were learning to live with one another and to accept the more liberal ideas of human rights and the freedom of ideas. The concept that ideas could not be forcefully imposed upon a people was a major step, and it was driven, according to Voltaire, by economic progress best represented by the London Stock exchange. Voltaire writes:

"Go into the Exchange in London, that place more venerable than many a court, and you will see representatives of all the nations assembled there for the profit of mankind. There the Jew, the Mahometan, and the Christian deal with one another as if they were of the same religion, and reserve the name of infidel for those who go bankrupt."

While it serves a stabilizing role on both a political and a social level, the possession of money and a reliable means of commerce is hardly a source of spiritual satisfaction to the individual. Though he has himself abandoned the church, Umberto Eco relays this point well in his essay, On God and Dan Brown, when he states:

“…if you believe in money alone, then sooner or later, you discover money's great limitation: it is unable to justify the fact that you are a mortal animal. Indeed, the more you try escape that fact, the more you are forced to realise that your possessions can't make sense of your death. It is the role of religion to provide that justification. Religions are systems of belief that enable human beings to justify their existence and which reconcile us to death.”

So man is left, ultimately, to struggle for that greatest of possessions – faith. And faith is really the ability to be confident. It is a confidence that one is right, a confidence one possesses knowledge of all the mysteries, and likewise a confidence that one must live by the tenets of that faith to be saved by it. Why is it, then, that men so often jeopardize the high ideals of faith during the pursuit of religious ends?

Inevitably, we must come to accept the fact that all human institutions are plagued by the same corruption: the human element. Our greed, pride, passion, self-absorption, lack of confidence, you name it – it will creep its way into the most noble of causes, and it has for hundreds of years. All our works are tainted. And that which fosters those flaws is so often the emotion which drove our earliest quests for survival: fear. Fear, and the instinctive reaction to conquer that fear through Possession.

Published on August 01, 2006 22:16

May 21, 2006

Treasure Madness

I went treasure hunting last weekend with a good friend of mine. It was a great trip. We had beautiful weather, a relaxing journey over miles of ocean and land, and plenty of hard work once we got to the site we were investigating. Treasure hunting should be hard work: wouldn't it be a bit anti-climactic to reach the location and see a big X on the ground, pick up a diamond and go home? OK, it sounds good, but really, isn't it the experience we seek, not the treasure. I don't think of myself as a treasure-hunter but rather an adventurer. What I really want is to solve the mystery, figure out the riddle, pass the test. If it's too easy, where's the glory?

Anyway, I was happy to have the company. For all my talk about hard work, I would have turned back early if I hadn't had such a willing conspirator eager to forge ahead. We came in search of one rock and found hundreds. We scoured the shoreline and bushwacked our way through thorns and undergrowth to find hidden meadows only deer and rabbit frequent now. We discussed the possibilities of erosion and the fickle decisions a pirate may have made with the landscape three hundred years ago. When all was said and done, and most of the potential spots had been investigated, there was one big rock that had attracted us from the beginning. We pulled out the compass and marched off the paces. Lo and behold, at the proper count the needle on the detector buried itself to the right.

Was it gold? No, it was part of a boiler, maybe. We found one more rock that looked like a suspect. Once again we counted out seven paces. Bam! the detector went crazy again.

Was it gold? No, just some lead bars that looked suspiciously like finger ingots. Now, I may be insane, but what are the chances that a treasure map would lead me to a beach where every rock had metal objects buried exactly seven paces to the northwest? Madness.

Was it gold? No, just some lead bars that looked suspiciously like finger ingots. Now, I may be insane, but what are the chances that a treasure map would lead me to a beach where every rock had metal objects buried exactly seven paces to the northwest? Madness.Nevertheless, I was happy to make the trip. I spent some great time with an old friend, and I felt that rush of adrenaline each time the detector went off. Alive is the best way to describe it. My neighbors and workplace associates think I am crazy, but I truly think they are the ones lacking clear judgement. We are grown-ups, and which of us didn't dream of being old enough to strike out on a real treasure hunt when we were young? As we grew up our childish dreams may have faded, but it doesn't have to be that way. Life is a series of decisions, and though they may seem laid out for us ahead of time, each moment is in our control, whether we recognize it or not. Live, and do what you wish you could. Life is gold.

Published on May 21, 2006 20:45

April 28, 2006

The One Ring

Some say the One Ring was lost when it fell into the Anduin.

I think Hugo would have liked to know. When the Duke of Egypt came into the square, the madness of the revolution had truly taken hold. Envision that scythe arching throught he crowd, cutting the legs out from under the horses of the king. Did they know what they were unleashing, could they have predicted Thermidor? And Esmerelda, whisked away, only to be lost forever?

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you

The Marriage of Quasimodo, and fear, in a handful of dust.

Frodo, nursing a hangover, stared at the envelope on the mantle, musing on the departure of his uncle. Did he fear what he did not understand? Did he wonder at footsteps and yearn for the return of another old friend? Did he watch for the door to open, or did he turn the handle himself?

What moss covered stone is this? Come in under the shelter of this red rock. We can dive for fish in the river. Or sit and weep by the banks.

Meanwhile, in the library, the careworn old man looked at all those books on the shelves. No one would read them. How many rooms full of how many books just gathering dust and crumbling into it? If you had a limited budget would you buy more books or an electronic service? He bent over the scrolls. In time he found it, that one parchment which explained it all. It was a scrap, really, waiting all its life to be read by this man, then fated to fall into obscurity. Now, he made for his horse as the kids surfed at the kiosk. He was so far from Bag End. He must make haste.

Kevin and the company of dwarves stood before the labyrinth and saw the host beckon them onward: on towards the most fabulous object. It was not what they sought that was of value, that empty sign which all filled with their hopes and dreams. It was what they had which was the prize, and a dangerous one at that. They saw not the trap, rushing for the goal: "Mom, Dad, don't touch it! It's evil"

Ahh yes, something about free will.

Anthony, Paul, Prester John, Benedict & Bonaventure. Newton, Dee, Bonny Prince Charlie, or maybe the Dutch, or Lorraine? Every one of Eco's Henchmen, Waite, Boehme, Eckhart, all the usual suspects lined up on the wall: who dropped the ball? Who swam across, betrayed by the moonlight?

Anyway, they all quit hiring painters and started consulting mediums, so its clear only the dead knew the secret. It died with someone. Yes, Hugo wished he knew. Belbo wished he knew. Bilbo held the knowledge in his hand, but never really understood.

Isildur, a fortnight dead,

Forgot the cry of gulls, and the deep seas swell

And the profit and loss.

A current under sea

Picked his bones in whispers. As he rose and fell

He passed the stages of his age and youth

Entering the whirlpool.

And Frodo stood by the dying embers of the fire, felt autumn coming on. He saw the grey leaves dying, twisting in the wind. He felt the cold air seeping in from the edges, and he wondered about all he knew. He gazed at the golden circle and pondered it, for good or ill. Miles away the shadow grew, and Gandalf raced towards the Shire. The rosy fingered dawn crept across the globe, outpacing any horse, and sought out its places: the craggy keyholes, the windows of the cathedrals, the chamber of Mazarbul.

Somewhere in the Shire a fish jumped and then settled back into his eddy. The brown waters circled under the stones by the river's edge. The sheep were coming down from the pasture to drink. The shepherdess was quiet. The One Ring lay heavy in the silt.

Published on April 28, 2006 20:04

March 20, 2006

Mixing Memory & Desire: An Arundel Tomb

We distort history everyday in our own lives, let alone in our distant comprehension of the lives of others. Memory, imagination, desire, fear and other emotions each taint the reality of the past, reforming it in our image.

Modern grail theory references occult knowledge which is based in hidden lore of mystery schools, passed down over hundreds of years through oral tradition. I am reminded of the children's game where we all stand in a line and repeat a whispered message, finding it drastically altered when it reaches the far end. I am also reminded of this poem by Philip Larkin, An Arundel Tomb:

Side by side, their faces blurred,

The earl and countess lie in stone,

Their proper habits vaguely shown

As jointed armour, stiffened pleat,

And that faint hint of the absurd -

The little dogs under their feet.

Such plainness of the pre-baroque

Hardly involves the eye, until

It meets his left-hand gauntlet, still

Clasped empty in the other; and

One sees, with a sharp tender shock,

His hand withdrawn, holding her hand.

They would not think to lie so long.

Such faithfulness in effigy

Was just a detail friends would see:

A sculptor’s sweet commissioned grace

Thrown off in helping to prolong

The Latin names around the base.

They would not guess how early in

Their supine stationary voyage

The air would change to soundless damage,

Turn the old tenantry away;

How soon succeeding eyes begin

To look, not read. Rigidly they

Persisted, linked, through lengths and breadths

Of time. Snow fell, undated. Light

Each summer thronged the grass. A bright

Litter of birdcalls strewed the same

Bone-littered ground. And up the paths

The endless altered people came,

Washing at their identity.

Now, helpless in the hollow of

An unarmorial age, a trough

Of smoke in slow suspended skeins

Above their scrap of history,

Only an attitude remains:

Time has transfigured them into

Untruth. The stone fidelity

They hardly meant has come to be

Their final blazon, and to prove

Our almost-instinct almost true:

What will survive of us is love.

— Philip Larkin (1922 - 85)

It is a marvelous examination of the idea that we often impress our own emotions onto our interpretation of history. When the facts are washed away by the years, we interpret what remains as we would like to see it. The great thing here is that Larkin's poem is itself tainted by the very point he makes. While it is true that the couple may not have been in love and the beauty that remains may be no more than the beauty imbued upon the pair through art, it may also be true that the love portrayed on the tomb was real, and Larkin has projected his own romantic pessimism onto it in his poem.

Perhaps the same may be said for the grail: many wish to claim possession of its mysteries. But whom of us know the truth, beyond the shadow left us by history? And if we convince ourselves that we do know, what have we known besides ourselves and our desires. They are projected out, only to be reflected back to us dimly, shadows rippling in the wine, winking at the brim of the chalice.

Modern grail theory references occult knowledge which is based in hidden lore of mystery schools, passed down over hundreds of years through oral tradition. I am reminded of the children's game where we all stand in a line and repeat a whispered message, finding it drastically altered when it reaches the far end. I am also reminded of this poem by Philip Larkin, An Arundel Tomb:

Side by side, their faces blurred,

The earl and countess lie in stone,

Their proper habits vaguely shown

As jointed armour, stiffened pleat,

And that faint hint of the absurd -

The little dogs under their feet.

Such plainness of the pre-baroque

Hardly involves the eye, until

It meets his left-hand gauntlet, still

Clasped empty in the other; and

One sees, with a sharp tender shock,

His hand withdrawn, holding her hand.

They would not think to lie so long.

Such faithfulness in effigy

Was just a detail friends would see:

A sculptor’s sweet commissioned grace

Thrown off in helping to prolong

The Latin names around the base.

They would not guess how early in

Their supine stationary voyage

The air would change to soundless damage,

Turn the old tenantry away;

How soon succeeding eyes begin

To look, not read. Rigidly they

Persisted, linked, through lengths and breadths

Of time. Snow fell, undated. Light

Each summer thronged the grass. A bright

Litter of birdcalls strewed the same

Bone-littered ground. And up the paths

The endless altered people came,

Washing at their identity.

Now, helpless in the hollow of

An unarmorial age, a trough

Of smoke in slow suspended skeins

Above their scrap of history,

Only an attitude remains:

Time has transfigured them into

Untruth. The stone fidelity

They hardly meant has come to be

Their final blazon, and to prove

Our almost-instinct almost true:

What will survive of us is love.

— Philip Larkin (1922 - 85)

It is a marvelous examination of the idea that we often impress our own emotions onto our interpretation of history. When the facts are washed away by the years, we interpret what remains as we would like to see it. The great thing here is that Larkin's poem is itself tainted by the very point he makes. While it is true that the couple may not have been in love and the beauty that remains may be no more than the beauty imbued upon the pair through art, it may also be true that the love portrayed on the tomb was real, and Larkin has projected his own romantic pessimism onto it in his poem.

Perhaps the same may be said for the grail: many wish to claim possession of its mysteries. But whom of us know the truth, beyond the shadow left us by history? And if we convince ourselves that we do know, what have we known besides ourselves and our desires. They are projected out, only to be reflected back to us dimly, shadows rippling in the wine, winking at the brim of the chalice.

Published on March 20, 2006 11:41