Matthew Rimmer's Blog, page 2

April 20, 2023

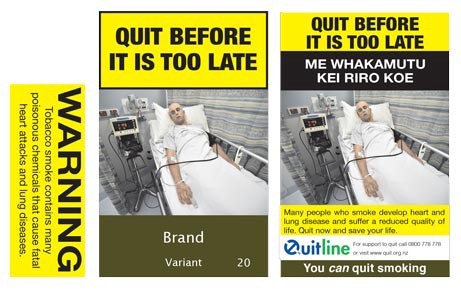

Queensland must adopt a tobacco endgame strategy

QUT Media, 13 April 2023

Rimmer, Matthew (2023) A Submission on the Tobacco and Other Smoking Products Amendment Bill 2023 (Qld): Health and Environment Committee, the Queensland Parliament. Health and Environment Committee, the Queensland Parliament.

Queensland must adopt a tobacco endgame strategy

13th April 2023

The elimination of smoking in Queensland should be the Government’s aim rather than just reducing smoking’s negative effects, a QUT law expert’s submission to the Queensland Parliament on its anti-smoking bill recommends.

Tobacco and other smoking products amendment bill 2023 (Qld) is before Parliament’s health and environment committeeSubmission welcomes the pioneering public health initiativeSubmission calls for raising of smoking ageLower density of smoking retailers, particularly in disadvantage areasClose loopholes to smoking enclaves in public spaces.Professor Matthew Rimmer, from QUT School of Law and the QUT Australian Health Law Research Centre, welcomed the legislative bill.

“The Queensland Government has shown commendable public health leadership with its commitment to tobacco control,” Professor Rimmer said.

“This Bill provides important law reforms — particularly in respect of smoke-free environments, retail licensing, and law enforcement.

“The Queensland Government has also shown a heartfelt commitment to the protection of human rights, including children’s rights, from the global tobacco epidemic.”

Professor Rimmer’s submission encourages the Government to update the objectives of its anti-smoking legislation to better reflect a tobacco endgame strategy.

“The Queensland Government could go even further with its anti-smoking legislation,” he said.

“The Bill and its legislative sponsors have focused on protecting children and youth from the tobacco industry and my submission calls for further age restrictions on smoking in Queensland to achieve smoke-free generations.

“By raising the legal age for smoking we would be following the lead of the United States, Singapore, and New Zealand.

“Further, we need a licensing regime for tobacco retailers in Queensland, combined with a reduction in the density and concentration of smoking retailers, particularly in disadvantaged neighbourhoods in Queensland.”

Professor Rimmer said Australia had led the world with plain packaging and other successful smoking reduction initiatives and the State Government has shown a strong commitment to safeguarding Queenslanders’ health from tobacco use.

“However, we could go further and close loopholes and anomalies in the law that still allow for smoking enclaves in public spaces,” he said.

“Furthermore, tobacco use has put a huge burden on people and the health system with smoking-related, death, disease and disability in Queensland.

“The Queensland Government should consider civil litigation and criminal litigation against the tobacco industry and hold them responsible and accountable for the billions of dollars of costs their products incur”.

Professor Rimmer said a further measure to achieve the tobacco endgame should be to guard against tobacco industry interference in Queensland’s political system.

“Tobacco companies and related entities should be banned from making political donations in the Queensland political system.

“We have a mismatch between the extent of the problem of smoking in Queensland, and the incremental nature of the public policy proposals proposed by the Queensland Government.

“The objective of Queensland’s tobacco control regime should aim higher than the reduction of smoking’s negative effects and work towards a smoke-free Queensland.”

QUT Media contacts:

Niki Widdowson, 07 3138 2999 or n.widdowson@qut.edu.au

After hours: 0407 585 901 or media@qut.edu.au.

[image error]March 6, 2023

The Right to Repair: Patent Law and 3D Printing in Australia

Matthew Rimmer

Script-ed Volume 20, Issue 1, February 2023

Matthew Rimmer*

Abstract

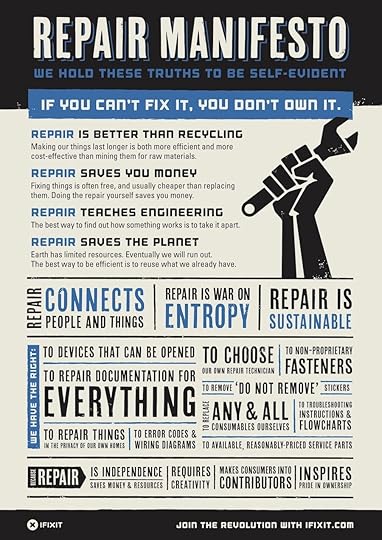

Considering recent litigation in the Australian courts, and an inquiry by the Productivity Commission, this paper calls for patent law reform in respect of the right to repair in Australia. It provides an evaluation of the decision of the Full Court of the Federal Court in Calidad Pty Ltd v Seiko Epson Corporation [2019] FCAFC 115 — as well as the High Court of Australia consideration of the matter in Calidad Pty Ltd v Seiko Epson Corporation [2020] HCA 41. It highlights the divergence between the layers of the Australian legal system on the topic of patent law — between the judicial approach of the Federal Court of Australia and the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia, and the endorsement of the patent exhaustion doctrine by the majority of the High Court of Australia. In light of this litigation, this paper reviews the policy approach taken by the Productivity Commission in respect of patent law, the right to repair, consumer rights, and competition policy. After the considering the findings of the Productivity Commission, it is recommended that there is a need to provide for greater recognition of the right to repair under patent law. It also calls for the use of compulsory licensing, crown use, competition oversight, and consumer law protection to reinforce the right to repair under patent law. In the spirit of modernising Australia’s regime, this paper makes a number of recommendations for patent law reform — particularly in light of 3D printing, additive manufacturing, and digital fabrication. It calls upon the legal system to embody some of the ideals, which have been embedded in the Maker’s Bill of Rights, and the iFixit Repair Manifesto. The larger argument of the paper is that there needs to be a common approach to the right to repair across the various domains of intellectual property — rather than the current fragmentary treatment of the topic. This paper calls upon the new Albanese Government to make systematic reforms to recognise the right to repair under Australian law.

Keywords

Patent law, patent validity, patent infringement, patent licensing, implied license, patent exhaustion, patent exceptions, crown use, compulsory licensing, competition policy, consumer protection law, the right to repair, 2D printing, 3D printing, additive manufacturing, digital fabrication, circular economy, sustainable development, Maker Movement, Maker’s Bill of Rights, iFixit, iFixit Repair Manifesto

Cite as: Matthew Rimmer, “The Right to Repair: Patent Law and 3D Printing in Australia” (2023) 20:1 SCRIPTed 130 https://script-ed.org/?p=4214

DOI: 10.2966/scrip.200123.130

* Dr Matthew Rimmer (BA/LLB ANU, PhD UNSW) is a Professor in Intellectual Property and Innovation Law at the Faculty of Business and Law in the Queensland University of Technology (QUT). He is the chief investigator in the ARC Discovery Project, ‘Inventing the Future: Intellectual Property and 3D Printing’ (2017–2021) (DP 170100758). Earlier versions of this paper have been delivered at the Right to Repair Symposium at Griffith University in 2020; the Copyright Law and Creative Industries conference in 2020; Remaking the Maker Movement in 2021; and the BEST Conference in 2021. This paper has also been informed by engagement with the Productivity Commission inquiry into the right to repair. The author would also like to thank the editors, and the peer reviewers for their useful and helpful feedback on drafts of this paper. This article was submitted and accepted in 2020 — and has been updated before publication in 2023.

[image error]October 25, 2022

Open for Climate Justice: Intellectual Property, Human Rights, and Climate Change

Matthew Rimmer

International Open Access Week 2022

International Open Access Week 2022Abstract

This commentary highlights the history of conflict and division over intellectual property, technology transfer, and clean technologies during international climate negotiations. It considers the scope for open licensing to make environmental knowledge, data, technology, and intellectual property more widely accessible and available in order to better address climate adaptation and mitigation, as well as loss and damage. There has been a renewed interest in open access models for climate research, knowledge, and data. Creative Commons, SPARC and EIFL have launched a 4 year Open Climate Campaign, with funding from the Arcadia Foundation. The theme for the Open Access Week 2022 is Open for Climate Justice. Patent pledges have become increasingly popular as a means of sharing technologies. The Low Carbon Patent Pledge was launched in 2021 by Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Microsoft, and Facebook. The Pledge is designed to help disseminate clean technologies, subject to intellectual property rights. Meanwhile, the Government of Canada has experimented with patent collectives in the field of clean technologies. Open government policies have increasingly focused upon climate data, knowledge, and technologies. The Biden administration has been seeking to promote open innovation in the United States. At an international level, there has been discussion about the relationship between open science and human rights. The UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science provides a framework for the further development of policies in this field. While such new open source projects have promise, there is a need to scale up initiatives on open access, open data, open science, and open innovation to better address the challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss, and sustainable development.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, international climate negotiations have hosted debates over intellectual property, technology transfer, and climate change (Rimmer, 2011; Rimmer, 2018a; Rimmer, 2019; Rimmer, 2021). Developed nations — along with technology developers — have demanded high standards of intellectual property protection and enforcement in respect of clean technologies. Mid-tier countries have called for better intellectual property licensing mechanisms, as well as a system of better climate finance. Developing countries have expressed concerns about the lack of climate finance to secure clean technologies. Such nations have called for wholesale reforms of intellectual property — especially in terms of flexibilities — in order to better achieve climate action and sustainable development. Least developed countries, small island states, and countries vulnerable to climate change have called for clean technologies to be openly shared and no doubt dedicated to the public domain. Given such divisions, international climate negotiations have struggle to reach a consensus on intellectual property and technology transfer between developed nations, and developing countries, least developed nations, and nations for vulnerable to climate change and global warming. No doubt the COP27 negotiations in Egypt will feature a similar debate as to whether there should be text on intellectual property, technology transfer, and climate change.

In the meantime, there has been increasing intellectual property litigation over clean technologies, green energy, and renewables. In the field of patent law, there have been conflicts over patent ownership of hybrid cars, solar technologies, and climate-ready crops. There have also been disputes under other regimes of intellectual property. There has been design law disputes over electric trucks. In the field of trade mark law, there has been debate over the use of green trade marks, eco-labels and certification systems. Under consumer law, there have been class actions and regulatory intervention over greenwashing by companies. Increasingly, clean technology companies have also taken action to protect confidential information and trade secrets against rivals and competitors. There have been trade disputes between the United States and China over intellectual property and climate change.

In this context of escalating conflict over intellectual property and clean technologies, there has been consideration of other co-operative measures, which could help promote the sharing of intellectual property, knowledge, and data related to the environment, biodiversity, and climate change. This commentary considers the scope for open licensing to make environmental knowledge, data, technology, and intellectual property more widely accessible and available in order to better address climate adaptation and mitigation, as well as loss and damage. Part 1 considers the Open Climate Campaign launched by the Creative Commons, SPARC and EIFL. Part 2 explores the establishment of the Open Carbon Patent Pledge as a mechanism to help share clean technologies. It also considers the new patent collective established by the Canadian Government — the Innovation Asset Collective. Part 3 examines the Open Government policies of the new Biden administration in the field of climate data and information. Part 4 focuses upon the connections between Open Science and Human Rights — with a particular emphasis on climate justice. In particular, it highlights the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science. This commentary concludes that there is a need to scale up open source initiatives in respect of climate data, knowledge, and technologies — particularly given the pressing need to engage in climate adaptation and climate mitigation.

1. The Open Climate Campaign

The Creative Commons movement was established to use open licensing to help share copyright work. The Science Commons was a spin off project from the Creative Commons. The Science Commons was designed to encourage the sharing of research, data, and inventions in the field of science. In 2009, the Science Commons established an environmental project with Nike Inc. and Best Buy called GreenXchange (Rimmer, 2011). Under the banner of GreenXchange, there was some sharing of patents by companies such as Nike Inc., Best Buy, and Yahoo. However, the project seemed to be short-lived. The Science Commons was folded back into the Creative Commons. The Creative Commons movement seemed to lose its interest in questions around the environment, sustainable development, and climate change for a while.

The Creative Commons slowly seemed to re-engage with issues around the environment, sustainable development, and climate change. The Sustainable Development Goals have become an important international framework — and the Creative Commons movement has particularly focused on education and access to knowledge within that framework.

There has been a renewed interest in open access models for climate research, knowledge, and data. In 2022, Creative Commons, SPARC and EIFL have launched a 4 year Open Climate Campaign, with funding from the Arcadia Foundation. The project highlights: ‘While the existence of climate change and the resulting loss of biodiversity is certain, knowledge and data about these global challenges and the possible solutions, mitigations and actions to tackle them are too often not publicly accessible’ (Granados and Green, 2022). The project stresses: ‘Addressing a challenge as dramatic as the climate crisis and its effects on global biodiversity will require that everything we know is available to everyone to understand and augment’ (Granados and Green, 2022). The project highlights: ‘The Campaign will go beyond just sharing climate and biodiversity knowledge, to expand the inclusive, just and equitable knowledge policies and practices that enable better sharing’ (Granados and Green, 2022).

Since the award of the grant, there has been an elaboration of the aims and goals of the Open Climate Campaign (2022): ‘The goal of this multi-year campaign is to promote open access to research to accelerate progress towards solving the climate crisis and preserving global biodiversity’. There are a number of steps that the Open Climate Campaign is taking to make the open sharing of research outputs the norm in climate science. The Open Climate Campaign highlights the need to bring attention to the issue of access to knowledge on climate change. The Open Climate Campaign seeks to support the open access review of climate and biodiversity research. The Open Climate Campaign (2022) calls for a clearance of legal and policy barriers: ‘We will create a strategic road map for breaking down and circumventing legal and policy barriers to support new open access incentives.’ The Open Climate Campaign (2022) observes: ‘We will also adapt existing and/or adopt new policies and incentives with governments and institutions to clear barriers to open knowledge.’

The Open Climate Campaign (2022) wants to help national governments to adopt and implement strong open access policies: ‘We will identify opportunities to engage national governments about opening publicly funded research outputs on climate and biodiversity, and help governments create, adopt and implement equitable open access policies.’ The Open Climate Campaign hopes to help research funders to adopt and implement strong open access policies.

The Open Climate Campaign seeks to encourage publishers to make their climate and biodiversity research open access. They also hope to help environmental organizations to adopt and implement strong open access policies. The Open Climate Campaign wants to engage with and contribute to international frameworks on climate and biodiversity.

The theme for the Open Access Week 2022 is Open for Climate Justice. The convenors have commented: ‘This year’s theme seeks to encourage connection and collaboration among the climate movement and the international open community’ (Open Access Week, 2022). The organisers observed: ‘Sharing knowledge is a human right, and tackling the climate crisis requires the rapid exchange of knowledge across geographic, economic, and disciplinary boundaries’ (Open Access Week, 2022).

2. Open Innovation and Climate Technologies

There has been some experimentation with open licensing in respect of clean technologies. Back in 2011, the author surveyed key proposals to share and distribute intellectual property relating to clean technologies through various co-operative means (Rimmer 2011). In 2018, the author put together a collection, which explored further developments in respect of intellectual property and climate change, with a particular focus on open data, open licensing, open innovation, and open government (Rimmer, 2018a). Writing now in 2022, it is notable that a number of the past open source projects have run their course, and there are a range of new emerging initiatives in this field.

Previously, there was interest in the use of patent pools to encourage the co-operative and collective utilisation of patents in respect of clean technologies. In 2008, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development established an Eco-Patent Commons to share intellectual property in respect of environmental knowledge and technology (Rimmer, 2011). David Kappos from IBM was the driving force behind the venture. The Eco-Patent Commons lost energy with the departure of David Kappos to the USPTO. The Eco-Patent Commons did not really scale up, and reach a critical mass in terms of technology developers and technology users. In the end, the Eco-Patent Commons has folded in 2016, with its technologies being distributed to WIPO GREEN (2015, 2022). Jorge Contreras, Bronwyn Hall and Christian Helmers (2018) have reflected upon the rise and fall of the Eco-Patent Commons, concluding that the project was a worthy failure: ‘This worthwhile effort should be viewed as an invitation to experiment further with, and to improve upon, the patent commons model both in the area of green technologies and beyond.’

There was a spike in interest in open licensing of clean technologies — when Elon Musk announced that Tesla would make its patents on electric vehicles available for open licensing (Rimmer, 2018b). However, this legacy proved to be somewhat more complicated than what the announcement would have suggested. There has been criticism that the terms of open licensing offered by Tesla are much more restrictive than necessary. There has not been much in the way of take-up of Elon Musk’s open licensing offer. Moreover, Tesla has been willing to enforce other forms of intellectual property — particularly in respect of trade secrets and confidential information against former employees and rival firms and competitors (Rimmer, 2018b). Thus, while Tesla does make the offer of open licensing in respect of some technologies, the company has also pursued closed, proprietary forms of intellectual property as well.

Professor Jorge Contreras from the University of Utah has undertaken extensive research on patent pledges — including in the field of clean technologies (Contreras, 2015; Contreras and Jacob, 2017; Contreras, 2018). Patent pledges have become increasingly popular as a means of sharing technologies. The Low Carbon Patent Pledge was launched in 2021 by Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Microsoft, and Facebook. The Pledge is currently administered by the InfoJustice program of the American University. Ben Altern from Hewlett Packard Enterprise has argued that making green patents free is a ‘force for good’ (Mehta, 2021). The Low Carbon Patent Pledge has been supported by the World Economic Forum.

The Low Carbon Patent Pledge aspires to share clean technology applications: ‘By making patents with low carbon technology applications freely available to all, we hope to encourage and accelerate the innovation humanity needs to avert a climate disaster’ (Low Carbon Pledge, 2022). The Low Carbon Patent Pledge was adopted by JPMorgan Chase, Micro Focus and Majid Al Futtaim in 2021. UPS, Lenovo, Alibaba, VIAVI Solutions and the Ant Group joined the Low Carbon Patent Pledge to accelerate climate solutions in 2022. Most recently, in August 2022, Panasonic has joined the Low Carbon Patent Pledge. At the time of writing (October 2022), 564 patents have been pledged by a dozen partners across thirteen countries under the Low Carbon Patent Pledge. It remains to be seen whether this venture will reach a critical mass. At present, the participants seem largely drawn from the information technology sector — there needs to be greater involvement from clean technology developers, energy companies, and utilities in the future.

There are of course limits to voluntary patent pledges by technology developers. Some commentators, such as Samuel Clayton (2020), have argued that there needs to be greater reform — with broader intellectual property exceptions and flexibilities in the field of climate change.

In 2020, the Government of Canada established a patent collective aimed at clean technologies. The Innovation Minister at the time, Navdeep Bains, was hopeful about the initiative: ‘It has a lot of potential to grow and create opportunities for Canadian businesses’ (Silcoff, 2019). The Innovation Asset Collective (2022) is an independent, membership-based not for profit, which is designed to assist Canadian small and medium-sized enterprises in the clean tech sector with their intellectual property needs. Jim Balsillie (2020) was supportive of the initiative: ‘Digital policy infrastructures such as IP collectives enable entrepreneurs and companies to access collective IP assets and use them to fortify their IP war chests, and to address freedom-to-operate issues with competitors who block their access to new markets.’

There has been increasing interest in the use of open source licensing in the field of clean technologies. In The Future We Choose, Christiana Figueres and Tom Rivett-Carnac (2020: 65) have expressed their hope that there would be greater use of open source strategies in respect of clean technologies: ‘As a next step, one could imagine a world of “open source everything”, an open approach in every field of human endeavour, where competition is no longer the operating principle but rather collaboration.’ Figueres and Rivett-Carnac (2020: 65) elaborate that ‘this approach explicitly promotes learning and growth throughout the system.’ Figueres and Rivett-Carnac (2020: 65) observe that an open source system ‘allows us to constantly teach one another, thereby exponentially increasing our capacity to co-create knowledge and share goods and services with open access, used by everyone for the benefit of all.’

There has also been discussion of placing intellectual property in the public domain. The Climate Action Network International (2012), least developed countries, and countries vulnerable to climate change have observed that clean technologies should be treated as global public goods — and made accessible and available to all. There have been discussions as to whether there should be greater recognition of public goods in international agreements (Heilprin, 2022). The International Council on Human Rights Policy (2016: 155) has argued: ‘The transfer of clean energy-generating and energy efficiency technologies, including know how, within a non-prohibitive IP regime must be seen as indispensable to the satisfaction of basic human rights in a climate-constrained future.’

There has been pressure for a reform of rules on intellectual property and climate change in international trade law (Rimmer, 2016). However, it has proven difficult to reform the international intellectual property system, even in the midst of a global emergency. Proposals for a TRIPS Waiver during the COVID-19 crisis were stymied by developed nations, such as Germany, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland, as well as vaccine developers, pharmaceutical drug companies, and the biotechnology industry. There have been parallel proposals mooted for a waiver of intellectual property rights in respect of clean technologies in the midst of the climate crisis — but no doubt such concepts would meet with resistance in international trade forums (Deane, 2021).

3. Open Government and Climate Change

In the area of climate change, there has been a call for information environmentalism — particularly in respect of the governance of data (Cunningham, 2018).

Travis Tai and James Robinson (2018) have called for the adoption of Open Science strategies to enhance climate change research: ‘Given that global efforts to combat climate change impacts will require both rapid collaborative research and communication among academics, policymakers and the public, climate change research is in urgent need of strong Open Science stewardship.’

The Obama Government made a number of innovations in respect of open government policies in the field of the environment and climate change. In particular, there was a strong open climate data movement. Bernadette Hyland-Wood (2018) has documented a variety of strategies deployed by the Obama administration to encourage the sharing of climate data and knowledge.

The Trump Administration was contemptuous of climate science, and undermined many of the efforts to make climate knowledge and technology available. Bernadette Hyland-Wood (2018) has discussed the problem of disappearing environmental data under the Trump Administration.

The Biden Administration has shown a renewed interest in pursuing open data, open government, and open science policies.

In January 2021, President Joe Biden issued an Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad. The executive order included a call for Federal agencies to develop ‘Climate Action Plans and Data and Information Products to Improve Adaptation and Increase Resilience’

The National Climate Taskforce Initiative has sought to provide more accessible climate information and decision tools: ‘With the climate crisis impacting every region and economic sector, federal agencies are working together to launch a coordinated effort to provide more robust information services that reach all communities.’

In September 2022, the Biden-Harris administration has launched a new climate portal to help communities navigate climate change impacts. The portal will provide a real-time monitoring dashboard, and assessments of local climate exposure. It will also centralize federal data, programs, and funding opportunities available to support climate resilience efforts.

Alondra Nelson, deputy assistant to the president and deputy director for Science and Society at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, has been particularly influential in carrying forward such open science policies. In a recent piece, ‘Public Access to Advance Equity’, Alondra Nelson — and co-authors Christopher Marcum and Jedidah Isler (2022) — stressed: ‘The American public should have access to the knowledge produced by the nation’s research and innovation enterprise.’ They specifically referred for the need for open research to facilitate climate action: ‘To live up to the administration’s national aspirations — to cut in half… greenhouse gas emissions,… [and] foster good and sustainable jobs in the coming decades, and more — the country first has much to learn from the open science movement.’ Alondra and her collaborators comment: ‘Open science has been part of ongoing efforts to expand public access, including democratizing the ability to set research agendas, to ask the important questions, and to generate and use knowledge.’

In a speech to the G7 in 2022, Alondra Nelson also discussed the importance of open science: ‘From our educations, and from our experiences, we know that openness is crucial to discovery — because science doesn’t move forward unless we publish, share, and communicate our knowledge and breakthroughs, so others can build on them’ (The White House, 2022a). She emphasized: ‘Without openness, fundamental research would never realize its potential.’ Nelson maintained that ‘openness is crucial to building and rebuilding public trust — in science, and in governments.’ She has encouraged other nation states to adopt similar policies in respect of open science.

Nelson has also been supportive of Open Innovation networks, noting: ‘Citizen science, prize competitions, challenges, and crowdsourcing bring more people, from more communities and more backgrounds than ever before into the missions of Federal science’ (The White House, 2022b). She commented: ‘These tools allow government to be more grounded in the priorities of the communities we serve’. Nelson noted that such open innovation initiatives ‘make government more agile and responsive to current and future problems we’ve yet to solve.’

4. Open Science and Human Rights

In 2020, there was a joint appeal for open science by OHCHR, CERN, UNESCO and WHO (WHO, 2020). The Geneva Call reaffirmed the ‘the fundamental right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications and advocate for open, inclusive and collaborative science.’ The statement noted that ‘Open Science can reduce inequalities, help respond to the immediate challenges of Covid19 and accelerate progress towards the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.’ The Geneva Call emphasized: ‘The core idea behind Open Science is to allow scientific information, data and outputs to be more widely accessible (Open Access) and more reliably harnessed (Open Data) with the active engagement of all stakeholders (Open to Society).’ The Geneva Call observed: ‘The Open Science movement has emerged from the scientific community and has rapidly spread across nations, calling for the opening of the gates of knowledge.’ The Geneva Call noted: ‘In a fragmented scientific and policy environment, a stronger global understanding of the opportunities and challenges of Open Science is needed.’

As UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet (2020) commented: ‘Worldwide people need States, international bodies, science and medical institutions and practitioners to ensure the broadest possible sharing of scientific knowledge, and the broadest possible access to the benefits of scientific knowledge’. She noted that open access to knowledge ‘is essential to the combat against climate change.’ Bachelet was concerned about the spread of climate misinformation, observing: ‘Everyone’s right “to share in scientific advancement and its benefits” has been attacked in recent years, particularly in the context of discussion of climate change.’ She warned: ‘This deliberate introduction of doubt about clear and factual evidence is catastrophic for our planet’. Bachelet commented: ‘This is a matter of saving individual lives; the future of communities and nations; and our planet.’ She concluded that ‘open science can help to unlock vital keys to recovery, and a better world.’

In 2021, the 41st session of the General Conference of UNESCO adopted the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science. The preamble of the text recognised ‘the urgency of addressing complex and interconnected environmental, social and economic challenges for the people and the planet, including poverty, health issues, access to education, rising inequalities and disparities of opportunity, increasing science, technology and innovation gaps, natural resource depletion, loss of biodiversity, land degradation, climate change, natural and human-made disasters, spiralling conflicts and related humanitarian crises.’ The preamble also noted ‘the vital importance of science, technology and innovation (STI) to respond to these challenges by providing solutions to improve human well-being, advance environmental sustainability and respect for the planet’s biological and cultural diversity, foster sustainable social and economic development and promote democracy and peace.’ The preamble highlighted ‘the transformative potential of open science for reducing the existing inequalities in [Science, Technology, and Innovation] and accelerating progress towards the implementation of the 2030 Agenda and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and beyond.’

The recommendation noted that ‘the practice of open science, anchored in the values of collaboration and sharing, builds upon existing intellectual property systems and fosters an open approach that encourages the use of open licensing, adds materials to the public domain and makes use, as appropriate, of flexibilities that exist in the intellectual property systems to amplify access to knowledge by everyone for the benefits of science and society and to promote opportunities for innovation and participation in the cocreation of knowledge.’ The recommendation further noted that ‘open science practices fostering openness, transparency and inclusiveness already exist worldwide and that a growing number of scientific outputs is already in the public domain or licensed under open license schemes that allow free access, re-use and distribution of work under specific conditions, provided that the creator is appropriately credited.’

The text of the recommendation discussed the aims and objectives of the recommendation; it provides a definition of open science; it discusses the core values and guiding principles of open science; it highlights areas of action; and considers mechanisms for monitoring progress in respect of open science.

The statement has asked ‘Member States [to] apply the provisions of this Recommendation by taking appropriate steps to give effect within their jurisdictions to the principles of this Recommendation.’ The statement requested ‘Member States [to] bring this Recommendation to the attention of the authorities and bodies responsible for science, technology and innovation, and consult relevant actors concerned with open science.’ The statement ‘further recommends that Member States collaborate in bilateral, regional, multilateral and global initiatives for the advancement of open science.’

Conclusion

This commentary has noted the historic stalemate over intellectual property and climate change in international climate talks. It has discussed the importance of open licensing models to achieve climate justice. This commentary has explored a number of new initiatives relying upon open source principles, strategies, and technologies. The Open Climate Campaign represents a new effort to encourage the use and adoption of open access model to share climate knowledge, data, and information. The Low Carbon Patent Pledge seeks to encourage co-operative behaviour in respect of intellectual property relating to clean technologies. The Canadian Government has established a patent collective to improve the development and dissemination of clean technologies. The Biden administration has been seeking to apply models of Open Government to better address its goals in respect of climate action and sustainable development. Moreover, there has been further discussion at an international level about the relationship between open science and human rights, culminating in the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science. While these new initiatives are promising, there is an urgent demand to scale up open source experiments in the field of climate data, knowledge, and technology — given the magnitude of the climate crisis.

Reference List

Bachelet, Michelle (2020), ‘A Joint Appeal for Open Science by CERN, OHCHR, UNESCO and WHO’, United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 27 October, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2020/10/joint-appeal-open-science-cern-ohchr-unesco-and-who

Balsillie, Jim (2020), ‘Long-awaited Patent Collective’s arrival one small step for Ottawa, one giant leap for Canada’s innovation economy’, Globe and Mail, 4 December, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/commentary/article-long-awaited-patent-collectives-arrival-one-small-step-for-ottawa/

Clayton, Samuel (2020), ‘The “Green Patent Paradox” and Fair Use: The Intellectual Property Solution to Fight Climate Change’, Seattle Journal of Technology, Environment, and Innovation, 11, 214–245.

Climate Action Network International (2012), ‘Tackling the Intellectual Property Elements of an Enabling Environment for Technology Transfer’, July, https://climatenetwork.org/resource/can-view-tackling-the-intellectual-property-elements-of-an-enabling-environment-for-technology-transfer-july-2012/

Contreras, Jorge (2015), ‘Patent Pledges’, Arizona State Law Journal, 47 (3): 543–608.

Contreras, Jorge (2018), ‘The Evolving Patent Pledge Landscape’, CIGI Paper №166, the University of Waterloo, https://www.cigionline.org/publications/evolving-patent-pledge-landscape/

Contreras, Jorge, Bronwyn Hall and Christian Helmers (2018), ‘Assessing the Effectiveness of the Eco-Patent Commons: A Post-mortem Analysis’, CIGI Paper №161, the University of Waterloo, https://www.cigionline.org/publications/assessing-effectiveness-eco-patent-commons-post-mortem-analysis/

Contreras, Jorge and Meredith Jacob (ed.) (2017), Patent Pledges: Global Perspectives on Patent Law’s Private Ordering Frontier, Cheltenham and Northampton (Mass.): Edward Elgar.

Cunningham, Robert (2018), ‘Climate Change and Open Data: An Information Environmentalism Perspective’, in Matthew Rimmer (ed.) (2018). Intellectual Property and Clean Energy: The Paris Agreement and Climate Justice, Singapore: Springer, 449–472.

Deane, Felicity (2021), ‘Climate Change Technology and the WTO: Will a TRIPS Waiver Support Technology Transfer? ’, in conference on The TRIPS Waiver: Intellectual Property , Access to Essential Medicines, and the Coronavirus, 10 December, https://eprints.qut.edu.au/227139/ and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xbwexoJWjFs

Figueres, Christiana and Tom Rivett-Carnac (2020), The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis, New York: Alfred Knopf.

Granados, Monica and Cable Green (2022), ‘Creative Commons Partners with SPARC and EIFL to Launch a 4-Year Open Climate Campaign’. Creative Commons, https://creativecommons.org/2022/08/30/cc-partners-with-sparc-and-eifl-to-launch-a-4-year-open-climate-campaign/

Heilprin, John (2022). ‘Advocates Mount New Initiative for WTO to Recognize ‘Public Goods’ in Trade Agreements — from Medicines to Forests’, Health Policy Watch, 30 September, https://healthpolicy-watch.news/a-push-for-public-goods-to-fight-pandemics/

Hyland-Wood, Bernadette (2018). ‘Open Government Data in an Age of Growing Hostility Towards Science’, in Matthew Rimmer (ed.) (2018). Intellectual Property and Clean Energy: The Paris Agreement and Climate Justice, Singapore: Springer, 473–514.

Innovation Asset Collective (2022), ‘Innovation Asset Collective’, https://www.ipcollective.ca/

The International Council on Human Rights Policy (2016), ‘Beyond Technology Transfer: Protecting Human Rights in a Climate-Constrained World’ in Joshua Sarnoff (ed.), Research Handbook on Intellectual Property and Climate Change, Cheltenham and Northampton (Mass.): Edward Elgar, 126–157.

Low Carbon Patent Pledge (2022), ‘Low Carbon Patent Pledge: Open Patents. Collaborative Innovation. Working Together to Solve the Climate Crisis’. https://lowcarbonpatentpledge.org/

Mehta, Rani (2021), ‘HPE IP Chief on Why Making Green Patents Free is “Force for Good”’, Managing IP, 29 November, https://www.managingip.com/article/2a5d0jj2zjo7faivn4a9s/hpe-ip-chief-on-why-making-green-patents-free-is-force-for-good

Nelson, Alondra, Christopher Marcum and Jedidah Isler (2022), ‘Public Access to Advance Equity’, Issues in Science and Technology, 39 (1), 33–35, https://issues.org/public-open-access-advance-equity-ostp-nelson-marcum-isler/

Open Access Week (2022), ‘Open for Climate Justice’, https://www.openaccessweek.org/theme

Open Climate Campaign (2022), ‘Open Climate Campaign’, https://openclimatecampaign.org/

Rimmer, Matthew (2011). Intellectual Property and Climate Change: Inventing Clean Technologies, Cheltenham and Northampton (Mass.): Edward Elgar.

Rimmer, Matthew (2016), ‘Trade Wars in the TRIPS Council: Intellectual Property, Technology Transfer, and Climate Change’ in Panagiotis Delimatsis (ed.), Research Handbook on Climate Change and Trade Law, Cheltenham (UK) and Northampton (Mass.): Edward Elgar, 200–229,

Rimmer, Matthew (ed.) (2018a). Intellectual Property and Clean Energy: The Paris Agreement and Climate Justice, Singapore: Springer.

Rimmer, Matthew (2018b), ‘Elon Musk’s Open Innovation: Tesla, Intellectual Property, and Climate Change’, in Matthew Rimmer (ed.) (2018). Intellectual Property and Clean Energy: The Paris Agreement and Climate Justice, Singapore: Springer, 515–551.

Rimmer, Matthew (2019), ‘Beyond The Paris Agreement: Intellectual Property, Innovation Policy, and Climate Justice’, Laws, 8 (1) https://www.mdpi.com/2075-471X/8/1/7

Rimmer, Matthew (2021), ‘Article 10 of The Paris Agreement — Technology Development and Transfer’ in L.S. Reins and Geert Van Calster, (ed). The Paris Agreement on Climate Change: A Commentary, Cheltenham (UK) and Northampton (Mass.): Edward Elgar, March 2021, 237–259

Silcoff, Sean, (2019). ‘Federal Government to Launch “Patent Collective,” giving Canadian Innovators Better IP Protection’, The Globe and Mail, 1 August, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-federal-government-to-launch-patent-collective-giving-canadian/

Tai, Travis and James Robinson (2018), ‘Enhancing Climate Change Research with Open Science’, Frontiers in Environmental Science, 6, Article 115, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2018.00115/full

UNESCO (2021), The UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science (adopted by the General Conference of UNESCO at its 41st session, in November 2021), https://en.unesco.org/science-sustainable-future/open-science/recommendation

The White House (2022a), ‘Readout of Dr. Alondra Nelson’s Participation in the G7 Science Ministerial: Progress Toward a More Open and Equitable World’, Office of Science and Technology Policy, 21 June, https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/news-updates/2022/06/21/readout-of-dr-alondra-nelsons-participation-in-the-g7-science-ministerial-progress-toward-a-more-open-and-equitable-world/

The White House (2022b), ‘Remarks of Dr. Alondra Nelson at the Innovation Forum on Building Equitable Partnerships’, Office of Science and Technology Policy, 20 July, https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/news-updates/2022/07/20/remarks-of-dr-alondra-nelson-at-the-innovation-forum-on-building-equitable-partnerships/

WIPO GREEN (2015), ‘Eco-Patent Commons Cross Lists Technologies with Royalty Free Access’, 9 March, https://www3.wipo.int/wipogreen/en/news/2015/news_0001.html

WIPO GREEN (2022), ‘WIPO GREEN — The Marketplace for Sustainable Technology’, https://www3.wipo.int/wipogreen/en/

World Health Organization and others (2020), The Geneva Call: A Joint appeal for Open Science, 27 October, https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/joint-appeal-for-open-science

Biography

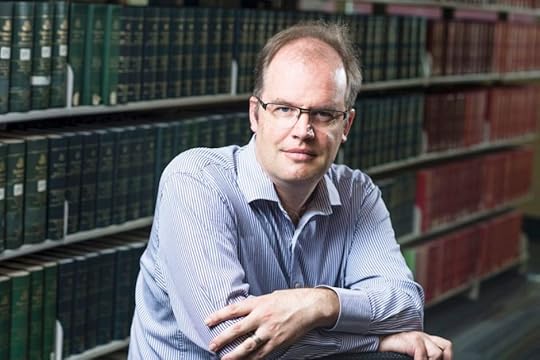

Dr Matthew Rimmer is a Professor in Intellectual Property and Innovation Law at the Faculty of Business and Law, at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT). He has published widely on copyright law and information technology, patent law and biotechnology, access to medicines, plain packaging of tobacco products, intellectual property and climate change, Indigenous Intellectual Property, and intellectual property and trade. He is undertaking research on intellectual property and 3D printing; the regulation of robotics and artificial intelligence; and intellectual property and public health (particularly looking at the coronavirus COVID-19). His work is archived at QUT ePrints, SSRN Abstracts, Bepress Selected Works, and Open Science Framework.

This piece was written as an Alternative Policy Solutions Policy Brief for the American University at Cairo (publication forthcoming)

[image error]May 17, 2022

Australia and Developed Nations must Share COVID-19 Technologies with the World

Press Release, QUT Media, 18 May 2022

18th May 2022

Australia and other national governments should follow the lead of the United States and share their intellectual property on COVID-19 technology through the World Health Organisation’s COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP), says QUT IP law expert Professor Matthew Rimmer.

US’s bold move to release publicly funded covid IP with the worldAustralia’s universities, medical research institutes and public research bodies could participateDeveloped countries resisting COVID-19 technologies patent waiverAssisting developing countries to make their own health tools would benefit everyoneProfessor Rimmer said President Biden had announced that the US would share critical COVID-19 technologies, owned by the US Government, including the stabilized spike protein that is used in many COVID-19 vaccines.

The announcement was made at the Global COVID-19 Summit on the weekend.

“The next Australian Government should consider participating in C-TAP and sharing its own technology and knowledge in respect of vaccines, diagnostics, and treatments to help tackle the Covid crisis,” Professor Rimmer said.

“Australian researchers at universities, medical research institutes, and public research bodies like CSIRO could have an opportunity to share the benefits of their research with the rest of the world.

“The approach of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) in sharing IP could be followed by other funding agencies around the world.

“The announcement should also encourage universities and public sector research organisations to engage in humanitarian licensing during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Professor Rimmer said WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus told the Summit attendees that empowering lower-income countries to manufacture their own health tools would ensure a healthier future for everyone.

“C-TAP arose out of a collaboration between Costa Rica and WHO but C-TAP’s operation has been limited and curtailed by key IP owners’ refusal to participate so the US Government’s sharing of its publicly-funded IP will breathe new life into C-TAP,” Professor Rimmer said.

Professor Rimmer said another ongoing initiative to share Covid technology with developing countries is the TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) Waiver in the World Trade Organisation.

“The Summit also heard a renewed call by South Africa for the adoption of a TRIPS Waiver by the WTO to suspend certain provisions of the TRIPS Agreement during the COVID-19 crisis.

“South African’s President Ramaphosa advocated for the waiver to cover patents on not only Covid vaccines but also therapeutics and diagnostics, calling on the global community to ‘ensure solidarity and equity underpin the next phase of the management of the pandemic’.

“Unfortunately, the debate over the TRIPS Waiver has been deadlocked and stonewalled by developed countries.

“South Africa and India have received backing for a broad TRIPS Waiver from many developing countries and least developed countries.

“The Biden Administration has supported a TRIPS Waiver for vaccines (which has been supported by nations like Australia, New Zealand, and Norway). However, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland have opposed a TRIPS Waiver.

“The US, EU, South Africa and India have been negotiating a compromise to the TRIPS Waiver, called the Quad Outcome Document, which is very limited in scope and has been endorsed only by the European Union.

“Predictably, vaccine developers, pharmaceutical companies, and the biotechnology industry have opposed various variants of the TRIPS Waiver, as well as the new Quad Outcome Document.”

QUT Media contacts:

Niki Widdowson, 07 3138 2999 or n.widdowson@qut.edu.au

After hours: 0407 585 901 or media@qut.edu.au.

Niki Widdowson, ‘Australia and Developed Nations Must Share COVID-19 Technologies with the World’, Press Release, QUT Media, 18 May 2022, https://www.qut.edu.au/news?id=181188

[image error]September 8, 2021

‘Right to repair’ movement pushes back against throwaway society

Australia must join the global ‘right to repair’ movement with a holistic reform of consumer, competition and environmental law to ensure recognition of consumers’ ‘right to repair’ goods rather than having to throw them out and replace them.

Internationally, consumer rights laws aim to make ‘built-in obsolescence’ obsoleteExpensive or discontinued spare parts major barrier to repairAuthorised repairers can charge exorbitantlyTablet and mobiles constantly need to be replaced ie ‘updated’ to copeSustainability awareness leads consumers to lower landfillProfessor of Intellectual Property and Innovation Law Matthew Rimmer said the US, EU, Canada and New Zealand had already made laws or were in the process of doing so to force manufacturers to repair their goods and to enable consumers to have items repaired at an outlet of their choosing.

Recognition of the right to repair would help foster a culture of responsible consumption and production in Australia,” Professor Rimmer, from QUT’s Faculty of Law, said.

“The right to repair is a critical issue of consumer rights and competition policy across a range of sectors.

“Australians and the global community are concerned about sustainability of the products they buy and are aware of the need to reuse and repurpose goods to keep them out of landfill.

“It makes economic and environmental sense to us all to be able to repair and maintain the things we buy.”

Professor Rimmer said a range of industry sectors were fighting for their right to repair:

Independent motor vehicle repairers have been lobbying for greater access to repair information and spare parts.The National Farmers Federation is concerned about onerous restrictions imposed on them for repairing expensive agricultural machinery and equipment.Everyday consumers have been raising concerns about barriers and cost of repairing phones and tablets for years.Professor Rimmer recently appeared before Australia’s Productivity Commission and argued for intellectual property law and policy reforms to support a right to repair.

“The Commission’s inquiry was set up to examine: ‘the potential benefits and costs associated with ‘right to repair’, including current and potential legislative, regulatory and non-regulatory frameworks and their impact on consumers’ ability to repair products that develop faults or require maintenance’,” he said.

“The Productivity Commission has released an issues paper and a draft report after holding hearings with a broad cross-section of stakeholders and the community.

“The draft report covers the fields of consumer law, competition policy, intellectual property, product stewardship, and environmental law, and has mooted copyright law reform and technological protection measures to better recognize the right to repair.

“The Federal Court has considered the spart parts exemption under designs law and the High Court of Australia has also ruled on patent exhaustion.

“However, there is a need for systematic law reform to support right to repair.”

Professor Rimmer has called for innovation policies to support a circular economy: ‘New South Wales has established a circular economy network — NSW Circular’.

“The Queensland Government could establish sustainability hubs and circular economy precincts following on from its establishment of advanced manufacturing hubs.

“Australia could also play a role in the network of United Nations Development Program Accelerator Labs designed to implement the various sustainable development goals.”

Professor Rimmer’s submission to the Productivity Commission Inquiry on the Right to Repair is on QUT ePrints: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/212034/

Niki Widdowson, ‘“Right to Repair” Movement Pushes Back against Throwaway Society’, Press Release, QUT Media, 8 September 2021, https://www.qut.edu.au/news?id=178481

July 25, 2021

A Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties on the Regional Comprehensive Economic…

(DFAT, Flickr, 2019, Creative Commons Attribution https://www.flickr.com/photos/dfataustralianaid/48492623767)

(DFAT, Flickr, 2019, Creative Commons Attribution https://www.flickr.com/photos/dfataustralianaid/48492623767)Submission

Matthew Rimmer, ‘A Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties on The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership’, Canberra: Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, Australian Parliament, April 2021, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Treaties/RCEP , QUT ePrints: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/210126, BePress Selected Works: https://works.bepress.com/matthew_rimmer/376/, SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3893279 and OSF: https://osf.io/3mvd9

Inquiry

Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, ‘The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership’, Canberra: Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, Australian Parliament, 2021, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Treaties/RCEP

Old Customs House, Rockhampton, (Author’s photograph)

Old Customs House, Rockhampton, (Author’s photograph)Executive Summary

This submission provides a critical analysis of the proposed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) — focusing in particular upon intellectual property and innovation policy.

Recommendation 1

RCEP has a broad membership — even with the departure of India from the negotiations. Nonetheless, there remain outstanding tensions between participating nations — most notably, Australia and China. The re-emergence of United States into trade diplomacy will also complicate the geopolitics of the Asia-Pacific.

Recommendation 2

The closed, secretive negotiations behind RCEP highlight the need for a reform of the treaty-making process in Australia, as well as the need for a greater supervisory role of the Australian Parliament.

Recommendation 3

In terms of intellectual property principles and objectives, RCEP promotes foreign investment and trade, and intellectual property protection and enforcement. The agreement needs a stronger emphasis on public policy objectives — such as access to knowledge; the protection of public health; technology transfer; and sustainable development.

Recommendation 4

RCEP establishes TRIPS-norms in respect of economic rights under copyright law.

Recommendation 5

The agreement does not though enhance copyright flexibilities and defences — particularly in terms of boosting access to knowledge, education, innovation, and sustainable development.

Recommendation 6

RCEP provides for a wide range of remedies for intellectual property enforcement — which include civil remedies, criminal offences and procedures, border measures, technological protection measures, and electronic rights management information. Such measures could be characterised as TRIPS+ obligations.

Recommendation 7

The electronic commerce chapter of RCEP is outmoded and anachronistic. Its laissez-faire model for dealing with digital trade and electronic commerce is at odds with domestic pressures in Australia and elsewhere for stronger regulation of digital platforms.

Recommendation 8

RCEP provides for protection in respect of trade mark law, unfair competition, designs protection, Internet Domain names, and country names.

Recommendation 9

As well as providing safeguards against trade and investment action by tobacco companies and tobacco-friendly states, RCEP should do more to address the tobacco epidemic in the Asia-Pacific.

Recommendation 10

RCEP has a limited array text on geographical indications, taking a rather neutral position in the larger geopolitical debate on the topic between the European Union and the United States.

Recommendation 11

RCEP has provisions on plant breeders’ rights and agricultural intellectual property. There is a debate over the impact of such measures upon farmers’ rights in the Asia-Pacific.

Recommendation 12

RCEP does not adequately respond to the issues in respect of patent law and access to essential medicines during the COVID-19 crisis. Likewise, RCEP is not well prepared for future epidemics, pandemics, and public health emergencies.

Recommendation 13

RCEP provides limited protection of confidential information and trade secrets — even though there has been much litigation in this field in the Asia-Pacific.

Recommendation 14

RCEP is defective because it fails to consider the inter-relationship between trade, labor rights, and human rights.

Recommendation 15

RCEP fails to provide substantive protection of the environment, biodiversity, or climate in the Asia-Pacific.

Recommendation 16

RCEP does little to reform intellectual property in line with the sustainable development goals.

Recommendation 17

RCEP does not adequately consider Indigenous rights — including those in the Asia-Pacific.

Recommendation 18

RCEP does not contain an investor-state dispute settlement mechanism. However, the Investment Chapter does have a number of items, which are problematic.

Biography

Dr Matthew Rimmer is a Professor in Intellectual Property and Innovation Law at the Faculty of Business and Law, at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT). He has published widely on copyright law and information technology, patent law and biotechnology, access to medicines, plain packaging of tobacco products, intellectual property and climate change, Indigenous Intellectual Property, and intellectual property and trade. He is undertaking research on intellectual property and 3D printing; the regulation of robotics and artificial intelligence; intellectual property and public health (particularly looking at the coronavirus COVID-19). His work is archived at QUT ePrints, SSRN Abstracts, Bepress Selected Works, and Open Science Framework.

Rimmer wrote his dissertation on The Pirate Bazaar: The Social Life of Copyright Law (2001). He is the author of Digital Copyright and the Consumer Revolution: Hands off my iPod (2007), Intellectual Property and Biotechnology: Biological Inventions (2008), Intellectual Property and Climate Change: Inventing Clean Technologies (2011) and The Trans-Pacific Partnership: Intellectual Property and Trade in the Pacific Rim (2020). Rimmer edited the thematic issue of Law in Context, entitled Patent Law and Biological Inventions (2006), Indigenous Intellectual Property (2015), the special issue of the QUT Law Review on The Plain Packaging of Tobacco Products (2017), and Intellectual Property and Clean Energy: The Paris Agreement and Climate Justice (2018), and co-edited Incentives for Global Public Health: Patent Law and Access to Essential Medicines (2010), Intellectual Property and Emerging Technologies: The New Biology (2012), and 3D Printing and Beyond: Intellectual Property and Regulation (2019).

Rimmer is a member of the QUT Centre for the Digital Economy — which is part of the QUT Centre for Future Enterprise; the QUT Digital Media Research Centre (QUT DMRC), the QUT Centre for Behavioural Economics, Society, and Technology (QUT BEST); the QUT Centre for Justice; the QUT Australian Centre for Health Law Research (QUT ACHLR); and the QUT Centre for Clean Energy Technologies and Processes. Rimmer was previously the leader of the QUT Intellectual Property and Innovation Law Research Program from 2015–2020 (QUT IPIL). Rimmer is a chief investigator in the NHMRC Centre of Excellence for Achieving the Tobacco Endgame (CREATE) — led by the University of Queensland.

Reference

Matthew Rimmer, ‘A Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties on The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership’ Canberra: Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, Australian Parliament, April 2021, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Treaties/RCEP , QUT ePrints: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/210126, BePress Selected Works: https://works.bepress.com/matthew_rimmer/376/, SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3893279 and OSF: https://osf.io/3mvd9

July 23, 2021

A Submission to the Productivity Commisson Inquiry on the Right to Repair

iFixit, Repair Manifesto, https://www.ifixit.com/Manifesto

iFixit, Repair Manifesto, https://www.ifixit.com/ManifestoMatthew Rimmer, A Submission to the Productivity Commission Inquiry on the Right to Repair, Melbourne: Productivity Commission, 23 July 2021, https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/current/repair#draft Bepress Selected Works, https://works.bepress.com/matthew_rimmer/381/ SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3891319 OSF: https://osf.io/p48bq

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Recommendation 1

The Productivity Commission is to be congratulated for producing a comprehensive discussion paper on the complex and tangled topic of the right to repair. Taking an interdisciplinary, holistic approach to the issue, the Productivity Commission shows a strong understanding that the topic of the right to repair is a multifaceted policy issue. Its draft report covers the fields of consumer law, competition policy, intellectual property, product stewardship, and environmental law. The Productivity Commission displays a great comparative awareness of developments in other jurisdictions in respect of the right to repair. The policy body is also sensitive to the international dimensions of the right to repair — particularly in light of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The Productivity Commission puts forward a compelling package of recommendations, which will be useful in achieving law reform in respect of the right to repair in Australia.

Recommendation 2

There is a strong body of evidence that intellectual property restrictions do impact upon the right to repair. The evidence is more than merely anecdotal or patchy (as suggested by Draft Finding 5.1). There has been threats of litigation in respect of copyright relating to repair manuals. The High Court of Australia and the Australian Parliament have expressed concerns about the breadth of technological protection measures. There has been major litigation over the spare parts exception under designs law. There has been major litigation over patent law, and the distinction between repair and refurbishment. There has been policy discussion about repair information and trade secrets — resulting in action by Treasury and the Australian Parliament.

Recommendation 3

This submission agrees with draft finding 5.1 that ‘copyright laws that prevent third-party repairers from accessing repair information (such as repair manuals and diagnostic data) appear to be one of the more significant intellectual property-related barriers to repair.’ The submission would also contend that other forms of intellectual property do also create significant barriers to repair, which need to be addressed by policy-makers.

Recommendation 4

This submission agrees with the recommendation of the Productivity Commission in Draft Finding 5.2 to ‘amend the Copyright Act 1968 to allow for the reproduction and sharing of repair information, through the introduction of a fair use exception or a repair-specific fair dealing exception’. The submission notes, though, that the Australian Federal Court has read the defence of fair dealing in a narrow fashion — and that could be problematic for a specific defence of fair dealing for repair. The submission contends that a broad defence of fair use under copyright law would be the best possible option.

Recommendation 5

This submission agrees with the recommendation of the Productivity Commission in Draft Finding 5.2 to ‘amend the Copyright Act 1968 to allow repairers to legally procure tools required to access repair information protected by technological protection measures (TPMs), such as digital locks’. This submission agrees with that the Productivity Commission that the Australian Government should ‘clarify the scope and intent of the existing (related) exception for circumventing TPMs for the purpose of repair.’ This submission notes the parallel development that the Parliament of Canada is currently considering a bill to amend its copyright regime to ensure that technological protection measures do not interfere with the right to repair.

Recommendation 6

This submission agrees with the recommendation of the Productivity Commission in Draft Finding 5.2 that ‘to reduce the risk of manufacturers using contractual arrangements (such as confidentiality agreements) to ‘override’ the operation of any such reforms, it may also be beneficial to amend the Copyright Act 1968 to prohibit the use of contract terms that restrict repair-related activities otherwise permitted under copyright law.’ This submission that this problem of contracting-out of repair is also apparent in other fields of intellectual property — such as designs law, trade mark law, patent law, and trade secrets law. It would be useful to prohibit the use of contract terms that restrict repair-related activities otherwise permitted under intellectual property law.

Recommendation 7

Unlike some of the other Australian intellectual property regimes, Australian designs law has a defence in respect of spart parts. The scope of this defence has been recently considered in the case of GM Global Technology Operations LLC v S.S.S. Auto Parts Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 97 (11 February 2019). Even though such a defence was effective in this particular case, the existing provisions in relation to spare parts are complicated and convoluted. The Productivity Commission should avail itself of the opportunity to design a broad defence for the right to repair under designs law.

Recommendation 8

In light of the Norwegian trade mark dispute between Huseby and Apple, and South African trademark litigation over replacement parts, and United States disputes over Lexus advertising cars, there is a need to ensure that trade mark law respects the right to repair. In its draft report, the Productivity Commission suggests that such an action for trade mark infringement against an independent repairer would be much harder. It would be helpful to clarify this position under Australian trade mark law by providing for an express defence or exception or limitation in respect of repair.

Recommendation 9

While the High Court of Australia has recently ruled on patent exhaustion, it would be helpful to clarify that the provision of repairs does not amount to patent infringement. Australian patent law recognises a defence of experimental use. However, it is not clear that the defence extends to repairs. A specific patent defence for repairs would provide reassurance about the legitimacy of conducting repairs. The compulsory licensing regime remains unwieldy at the moment — but in exceptional circumstances could be used to provide access to inventions for the purposes of repair on competition grounds.

Recommendation 10

Australia provides for civil remedies in respect of trade secrets, as well as criminal offences in respect of violation of trade secrets by foreign principals. However, the nature and scope of defences for trade secrets remains unclear. There has been debate as to whether there is a general interest defence (as espoused by Kirby J) or a narrow defence related to exposing wrongdoing and iniquity (as recommended by Gummow J). In this context, there is currently a lack of clarity as to whether using trade secrets for the purposes of repair would be allowable. The Productivity Commission should consider making recommendations regarding defences in respect of trade secrets relating to repair.

Recommendation 11

Treasury has established a motor vehicle service and repair information sharing scheme. However, it is problematic that this information sharing scheme has been industry-specific. There was also a failure to consider how that scheme would interact with other disciplines of law — like intellectual property. There is a need for a more general system regarding the sharing of repair information for all technologies and industries. It would be desirable to go beyond the model of self-regulatory codes of conduct, and establish binding standards in respect of sharing repair information.

Recommendation 12

This submission supports the finding 3.1 of the Productivity Commission that ‘there is scope to enhance consumers’ ability to exercise their rights when their product breaks or is faulty — by providing guidance on the expected length of product durability and better processes for resolving claims.’ This submission also supports the recommendations of the Productivity Commission in respect of guidance on reasonable durability of products (draft recommendation 3.1); powers for regulators to enforce guarantees (draft recommendation 3.2); and enabling a super complaints process (draft recommendation 3.3). The Productivity Commission has also asked for information as to whether consumers have reasonable access to repair facilities, spare parts, and software updates (information request 3.1). There is a need to ensure that businesses are required to hold physical spare parts and operate repair facilities for fixed periods of time. It is also important to ensure that software updates are provided by manufacturers for a reasonable period of time after the product has been purchased.

Recommendation 13

This submission notes the finding of the Productivity Commission that there have been misleading terms in warranties for mobile phones, gaming consoles, washing machines, and high-end watches regarding independent repairs. This submission supports the recommendation of the Productivity Commission (draft recommendation 4.2) that ‘the Australian Government should amend r. 90 of the Competition and Consumer Regulations 2010, to require manufacturer warranties (‘warranties against defect’) on goods to include text (located in a prominent position in the warranty) stating that entitlements to consumer guarantees under the Australian Consumer Law do not require consumers to use authorised repair services or spare parts.’ This submission supports the suggestion of the Productivity Commission that Australia should adopt provisions similar to the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act in the United States, which prohibit manufacturer warranties from containing terms that require consumers to use authorised repair services or parts to keep their warranty coverage.

Recommendation 14

There is scope for the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission to deploy competition law to address repair issues. As Draft Finding 4.3 notes, ‘there are existing remedies available under Part IV of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 to address anti-competitive behaviours in repair markets, such as provisions to prevent the misuse of market power, exclusive dealing or anti-competitive agreements.’ The Productivity Commission has highlighted in Draft Finding 4.2 that limits to repair supplies could be leading to consumer harm in some repair markets — including agricultural machinery, and mobile phones and tablets. A positive obligation to provide access to repair supplies could be a useful means of mandating access to repair supplies — including repair information, spare parts, and diagnostic tools.

Recommendation 15

The submission would argue that additional policies to prevent premature product obsolescence would have net benefits to the community (cf the Productivity Commission’s Draft Finding 6.1). This submission notes that a product labelling scheme could address information gaps in respect of product repairability, durability, and environmental impact (Information Request 6.1). There are various precedents in respect of energy labelling, eco-labelling, and carbon labelling. The submission supports the adoption of a French-style ‘repairability index’ in Australia. The submission would argue that e-waste is a significant problem in Australia, and there is a need to shift towards the adoption of sustainable production and consumption as part of a circular economy. The submission supports the recommendation 7.1 of the Productivity Commission that the Australian Government should amend the National Television and Computer Recycling Scheme (NTCRS) to allow e-waste products that have been repaired or reused by co regulatory bodies to be counted towards annual scheme targets.

Recommendation 16

Australia should reform the Product Stewardship Act 2011 (Cth) in order to promote the right to repair, reduce e-waste, and support a circular economy and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Recommendation 17

The Productivity Commission should be encouraged to develop a bold package of proposals to support a right to repair in Australia — especially given the recent, rapid developments on the right to repair at a state and a federal level in the United States. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission should prioritize enforcement action in respect of repair restrictions — like its counterpart the United States Federal Trade Commission.

Recommendation 18

The Productivity Commission should take note of proposal in the Parliament of Canada to recognise a right to repair under copyright law and technological protection measures, which has received broad support from the various quarters of political parties in the Canadian political system.

Recommendation 19

The Productivity Commission should take note of the developments in the United Kingdom in respect of the right to repair — which are intended to mirror the European Union.

Recommendation 20

The Productivity Commission should take into account developments on the right to repair in the European Union — particularly given their strong focus on promoting eco-design, green business, a circular economy, and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Recommendation 21

The Productivity Commission should take into account the push for a broader and stronger right to repair in South Africa — particularly in response to the coronavirus public health epidemic. The Productivity Commission should also consider how the prospect of a WTO TRIPS waiver would enable access to medical technologies (including for repair) during the public health emergency.

Recommendation 22

Given that New Zealand has been lagging in this field, Jacinda Ardern’s New Zealand Government should adopt a package of reforms to realise a right to repair in New Zealand.

Recommendation 23

Australian governments should support repair cafes and social enterprises, makerspaces and fab labs, research centres and innovation networks, which are focused on responsible production and consumption. NSW Circular could be a model for the Federal Government, and other states and territories in Australia. There is a need to recognise a right of repair in Australia in order to help implement Sustainable Development Goal №12, which is focused on responsible production and consumption. As a funder, host, and participant, Australia should support the UNDP Accelerator Labs Network programme.

Recommendation 24

3D printing and additive manufacturing are already playing a significant role in respect of repair across a number of sectors and technologies. There is a need to ensure that intellectual property law enables the use of such technologies for the purposes of repair. Product liability may have an impact in respect of defective repairs conducted with 3D printing (much like in other fields of technology). The development of standards will also be important to ensure the quality, reliability and durability of repairs undertaken with 3D printing.

Recommendation 25

The draft report by the Productivity Commission briefly discusses in passing some of the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic upon the topic of the right to repair. It would be helpful and useful if the Productivity Commission could devote a chapter or a sub-chapter to the topic of public health and the right to repair (much like it has in respect of intellectual property, consumer rights, competition policy, product design, and e-waste). There has been much discussion of the necessity of law reform during the coronavirus emergency — including in respect of intellectual property and the right to repair.

Biography

Dr Matthew Rimmer is a Professor in Intellectual Property and Innovation Law at the Faculty of Business and Law, at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT). He has published widely on copyright law and information technology, patent law and biotechnology, access to medicines, plain packaging of tobacco products, intellectual property and climate change, Indigenous Intellectual Property, and intellectual property and trade. He is undertaking research on intellectual property and 3D printing; the regulation of robotics and artificial intelligence; intellectual property and public health (particularly looking at the coronavirus COVID-19). His work is archived at QUT ePrints, SSRN Abstracts, Bepress Selected Works, and Open Science Framework.