Randal Rauser's Blog, page 42

December 12, 2020

The Awfulness of Franklin Graham in a Single Tweet

The post The Awfulness of Franklin Graham in a Single Tweet appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 11, 2020

Atheists and Free-Thinkers: Are they the same thing?

Source: https://www.deviantart.com/samusfairc...

In this article, I continue my series on atheism. In the previous installment, we looked at the relationship between atheism and scientism. In this installment, we consider the relationship between atheism and free-thought. Note, this article is in part based on my article “The Myth of the Free-thought Parent.”

Next, we turn to free-thought, a notion that is intimately connected to atheism in the popular mind. For an excellent demonstration of the perceived link we can consider how Dan Barker describes his own conversion from Christianity to atheism:

“I was not converted by the “atheist movement.” I saw no atheist evangelist on TV who persuaded me to change my views. I came to it all on my own, and that’s how it should be. Almost every other atheist and agnostic I have met since then, who was raised religious, tells the same story: it is a private, independent process of free thinking. That is what gives it strength. It makes my conclusions my very own, valued because of the precious process of being forged and proved in my own mind.”

Barker goes on to describe with eloquence and concision how he perceived his conversion to atheism to consist equally of a conversion to free thinking: “I prefer the winds of freethought to the chains of orthodoxy.”

Barker is not alone in this linking of atheism with the notion of free-thought and the wider free-thought movement. And it is easy to see why the connection is drawn. Most theists are religious, and as such they tend to accept their theism as part of a larger package of belief which involves submission to some ecclesial authority that is perceived to be the reliable propagator of authoritative doctrine concerning spiritual matters. The advocate of free-thought, in turn, disavows such authorities and instead endorses free-thinking shorn of tradition and uncritical acquiescence to authoritative testimony. As David Hume famously said, “If we take in our hand any volume; of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance; let us ask, Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.” Hume’s sentiment would become a mantra of the Enlightenment: think for yourself! Don’t laden yourself down with the opinions of the past. Discover the truth for yourself. Therein lies the essence of true free-thought. (Of course, it is no small irony that Hume’s great commendation of free-thought advocates for book burning and thus censorship.)

Another notable example is found in T.H. Huxley’s famous essay “Agnosticism” in which he describes how he arrived at the conviction that his party affiliation was, above all, that of the free-thinker:

“When I reached intellectual maturity and began to ask myself whether I was an atheist, a theist, or a pantheist ; a materialist or an idealist ; a Christian or a freethinker ; I found that the more I learned and reflected, the less ready was the answer ; until, at last, I came to the conclusion that I had neither art nor part with any of these denominations, except the last.”

While Huxley famously identified as an agnostic, one sees here a close link between the free-thinker and the skeptical attitude toward religion defended by atheist and agnostic alike.

Not surprisingly, on several occasions I’ve encountered the objection that Christian faith inhibits free-thinking. Some years ago while I was delivering a lecture on faith and reason at a secular university, I informed my audience that I had taught the Apostles’ Creed to my daughter, who was four or five at the time. To drive the point home, I added that as a family we recited the creed every day during our family devotions. As I expected, the audience was disturbed by my revelation. One of the students spoke for many when she insisted that children should be raised without “religious dogma,” free to “make up their own minds” about what to believe. Parents could licitly inform their progeny of the various options, she opined, but they should be impartial in presenting the various views so their children may be free to decide for themselves, unencumbered by undue external influence.

One commonly encounters this ideal of the dispassionate, objective parent in the free-thought movement. And it is regularly linked to atheism. Consider, for example, this passage from Catie Wilkins’s essay “110 Love Street”:

“My dad, a supremely rational man, even when addressing four-year-olds, answered my question, “what happens when you die?” logically and truthfully. He replied, “No one really knows, but we have lots of theories. Some people believe in heaven and hell, some people believe in reincarnation, and some people believe that nothing happens.” The other four-year-olds were not privy to the open, balanced information that I had, leaving me the only four-year-old to suggest that heaven might not exist.”

Wilkins believed her father’s pedagogical advice provided an empowering and non-dogmatic way to instruct a small child by dispassionately and objectively providing the range of views on a given issue and allowing the child to make her own decision. In short, Wilkins’s father provided a precise contrast with my dogmatizing bequeathal of the Apostles’ Creed to my unwitting progeny.

If Wilkins’s anecdote exemplifies the ideal of the free-thought parent, it also exemplifies the inherent tensions and even contradictions with this ideal. We can begin to illumine those problems by changing up the scenario. Imagine that instead of posing a theological question about life after death, the child posed an ethical query about the nature of the good and the right. So here’s the scenario: after overhearing a disturbing murder story on the evening news where an innocent man is killed for his money, the child turns to her father and poses the question: “Daddy, is it always wrong to kill somebody just because you want their money?”

Questions about the good and the right, like questions about the afterlife, are beset with controversy. With that in mind, our free-thought dad obligingly gives his non-dogmatic and dispassionate reply in which he offers a survey of ethical views, all in the hope that the child may form her own opinions unencumbered by undue external influence. This is how he puts it:

No one really knows, but we have lots of theories. Some people believe it is absolutely wrong because it violates moral virtue or a moral law. But other people believe it could be right if doing so increased the overall happiness in society. Still others believe that each individual must decide what is right for them, and if money makes them happy then they can rightly kill for it.

I suspect most people will find the father’s response in the second scenario to be problematic (to say the least!). And I share that assessment. But what, exactly, is wrong with it? Let’s consider two problems.

To begin with, the father’s answer is wholly inappropriate for the cognitive level of a four year old. Granted, ethicists disagree over questions like whether it is always wrong to kill somebody for money, but it doesn’t follow that a four year old is ready to process that entire controversy. At this age they need a simple answer. Complexity and nuance can (and indeed should) be acquired at a later date, but a child needs a simplified place to begin from which they can gradually come to grasp that complexity and nuance over time.

And what kind of simple answer should one give? Presumably, the answer that best approximates what the parent believes to be true, albeit adjusted for the cognitive capacity of the child. For example, if the father believes it is wrong to kill people just because you want their money, then that’s the answer he should give: “Yes, it’s wrong to kill people just because you want their money.” (And if he doesn’t believe this, one hopes his daughter’s pointed question might provide an occasion to reconsider his own view.)

The second problem with the response is that it is not nearly as free and uncommitted as one might think. Despite his alleged neutrality as regards the ethical question, the father is surprisingly committed and dogmatic when he prefaces his comment with the proviso, “No one really knows…” This is most certainly not a neutral statement. Instead, it is a robust epistemological claim about the alleged lack of knowledge that others have on ethical matters. In short, while the father may not espouse any particular ethical view, he does commend to his child a strong agnosticism as regards all ethical views on the topic, and as I said that is not neutral.

The same points that apply to ethics apply to theology and the afterlife as well. If the father is a strong agnostic about the nature of posthumous existence, that is, if he is persuaded that nobody really knows what happens after death, then he is free to tell his child that nobody really knows. But he should not delude himself into thinking that this perspective is somehow neutral, for it surely isn’t. He is commending a strong agnosticism to his child and if he is successful, she will grow up to hold the same view, just like Catie Wilkins did.

And what of the father whose beliefs about the afterlife are not agnostic but rather Christian, and thus which include convictions about the general resurrection, heaven, and hell? If the strong agnostic is permitted to raise up his child in the belief that nobody knows what happens when you die, then why isn’t the Christian parent permitted to raise up his child in the belief that some people do know?

Intelligent people can disagree about how children ought to be raised. And that’s precisely the point: the fact is that there is no neutral way for a parent to raise a child or field their questions. Every answer you give is sourced in particular beliefs, value judgments, and a broader view of the world. As a result, it is best that we all recognize that parenting involves, among other things, the desire to inculcate in one’s children that set of beliefs and values that one holds to be true. To be sure, those of us who value fairness and objectivity and a healthy recognition of one’s own cognitive biases will hope that all parents will include those same values in their education. But we hope for that not because that hope is neutral or value free. Rather, we hope for it because it is in this bequeathal of self-awareness of one’s own limitations and generosity toward others that true free-thought is found. It is most certainly not found in the delusion that a dogmatic agnosticism or skepticism toward a particular subject matter is somehow neutral or objective or value free.

But that’s enough with critiquing the popular ideals of free-thought. Let’s return to the alleged link between free-thought and atheism. Again, it isn’t hard to see why the popular link exists. As I noted, atheism is in itself a minimal claim which lacks dogmatic constraints. Granted that could change if atheism were melded with a more robust belief system like materialism. But left unto itself, atheism just is a minimal denial of belief in God. This certainly does leave a lot of room for free-thought.

What is more, atheism is widely viewed as something of a “rebel” position, insofar as folks typically arrive at atheism only after rejecting a system of belief. And that very act of rejecting a system of belief appears to many to be indicative of free-thinking.

At the same time, we should appreciate the fact that a person can certainly be raised with a secular, atheistic, and/or free-thought mindset in such a way that this education itself inhibits critical thinking and true free-thought. And this brings me back to the discussion above regarding the inescapability of intellectual formation. Barbara Ehrenreich wryly makes just this point as she reflects on her own upbringing in a house that allegedly valued free-thought:

“I was raised in a real strong Secular Humanist family—the kind of folks who’d ground you for a week just for thinking of dating a Unitarian, or worse. Not that they were hard-liners, though. We had over 70 Bibles lying around the house where anyone could browse through them—Gideons my dad had removed from the motel rooms he’d stayed in. And I remember how he gloried in every Gideon he lifted, thinking of all the traveling salesmen whose minds he’d probably saved from dry rot.

“Looking back, I guess you could say I never really had a choice, what with my parents always preaching, “Think for yourself! Think for yourself!”

We should not miss the irony of this picture. The image of Ehrenreich’s parents fervently instructing her to think for herself creates a nice paradox. After all, if she follows their advice, then she isn’t thinking for herself!

Ehrenreich’s amusing recollection provides the resources for us to get a handle on the true nature of free-thought. It seems to me that the assumption that one secures free-thought by starting out with a minimum of metaphysical, ethical, and social commitments such as one might find in atheism is quite mistaken. After all, for all his absence of dogma, Ehrenreich’s father seems surprisingly dogmatic. Moreover, as we have seen atheism has often been presented with a particular system of belief like classic materialism, and that system can itself provide limited constraints on free-thought.

The lesson, I would suggest, is that true free-thought is secured not by minimizing belief commitments, still less by adopting atheism. Rather, it is cultivated by developing rational epistemic virtues and becoming aware of one’s own biases as one continually recommits to the dogged pursuit of truth. And one can do that whether one is an atheist, or a theist, or anything in between.

Dan Barker, Godless: How an Evangelical Preacher Became One of America’s Leading Atheists (Berkeley, CA: Ulysses Press, 2008), 41.

Barker, Godless, 103.

Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, edited by Eric Steinberg, 2nd ed. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1993), 114.

Huxley, “Agnosticism,” in Agnosticism and Christianity and Other Essays (New York: Prometheus, 1992),162.

“110 Love Street,” in ed. Ariane Sherine, There’s Probably No God: The Atheist’s Guide to Christmas (London: Friday, 2009), 21-22.

So why does our free-thought dad believe nobody knows the nature of right and wrong? What is his evidence for believing this? What provides his justification? One suspects that his strong agnosticism is based on an assumption like this: if experts disagree on a particular topic, then one cannot know what the right answer is on that topic. Based on this principle, one might conclude that if ethicists disagree about the wrongness of an action like killing for money, then we cannot know if that action is indeed wrong. While this assumption might seem reasonable at first blush, the fact is that it is self-defeating. While free-thought dad’s belief that unanimity is required for belief is an epistemological claim, epistemologists do not all agree with it. Thus, if we accept that assumption then we ought to reject it. In other words, unanimity among experts is not required before one can hold a reasonable belief, or make a knowledge claim, on a particular topic. And so the father is free to tell his daughter that it is always wrong to kill other people for money, even if he is aware of ethicists who disagree with him..

Cited in Randal Rauser, You’re not as Crazy as I Think: Dialogue in a World of Loud Voices and Hardened Opinions (Colorado Springs, CO: Biblica, 2011), 65.

The post Atheists and Free-Thinkers: Are they the same thing? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 10, 2020

Is the Christian God Worthy of Worship?

I will be debating Dan Barker right before Christmas on the topic “Is the Christian God Worthy of Worship?” Barker’s recent book God: The Most Unpleasant Character in All Fiction will undoubtedly be a big part of the discussion.

The post Is the Christian God Worthy of Worship? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 8, 2020

One of the most outrageous things a Christian apologist ever said

The post One of the most outrageous things a Christian apologist ever said appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 7, 2020

Are evangelicals people of truth? Maybe not.

The post Are evangelicals people of truth? Maybe not. appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 5, 2020

What is sin?

The post What is sin? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 4, 2020

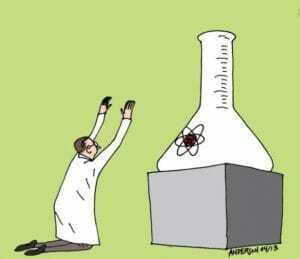

Do atheists worship science?

This article continues my survey of how atheism relates to other (commonly associated) concepts. Previously, I addressed skepticism and materialism. In this installment, we take on scientism.

This article continues my survey of how atheism relates to other (commonly associated) concepts. Previously, I addressed skepticism and materialism. In this installment, we take on scientism.

Over the years, the great naturalist E.O. Wilson has appeared to court deism. But deism is merely a footnote in his book Consilience. The beating heartbeat of that book is Wilson’s conviction — dare we call it faith? — that scientific inquiry might one day provide a unified and all-encompassing understanding of reality. Wilson recalls that his own drive to understand the world was born in childhood: “I saw science, by which I meant (and in my heart I still mean) the study of ants, frogs, and snakes, as a wonderful way to stay outdoors.” Amen to that! However, for Wilson that initial love of science gave birth to the staggering vision that a completed science could one day provide a comprehensive explanation of the totality of existence ranging from the trajectory of a subatomic particle straight up to the beauty of a Schubert sonata.

Wilson’s Consilience provides an eloquent defense of scientism, the idea that natural science is the paradigm and model for all knowledge. But my favorite succinct definition of scientism comes from philosopher Wilfred Sellars who clearly took his inspiration from Protagoras. He wrote: “science is the measure of all things, of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not.” Even more concise is Richard Lewontin: “Science is the only begetter of truth.” The common idea is that genuine knowledge is properly scientific, that science provides a unique and authoritative window on existence.

Scientism fits well with naturalism, for if the closed system of nature exhausts reality then it is not a leap to expect that the rigorous scientific study of that world would exhaust knowledge of reality. So it isn’t surprising that contemporary atheists often view themselves as closely aligned with science while touting their very high estimation of the power and promise of scientific inquiry. The perception is reinforced by the fact that some prominent scientists are deeply involved in the polemical defense of atheism, the late astronomer Victor Stenger and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins (widely touted as the world’s leading atheist) being among them. As Stenger puts it, “The new atheists write mainly from a scientific perspective.” He adds that in his view this accounts for their dismissiveness of other forms of knowledge discourse, specifically theology: “All of us have been criticized for not paying enough attention to modern theology. We are more interested in observing the world and taking our lessons from those observations than debating finer points of scriptures that are probably no more than fables to begin with.”

Underlying Stenger’s optimistic view of science as a key to unlocking all reality is a commitment to a set of claims he refers to as “Scientific naturalism.” He summarizes this view with several principles including a belief that God does not exist, nature is “self-originating,” and the following apparent endorsement of scientism: “all explanations, all causes are purely neutral and can be understood only by science.” Given examples like this, it is hardly surprising that many people link atheism to scientism.

But while it is popular to link scientism to atheism, the fact is that we can find theists endorsing scientism and atheists repudiating it. As an example of the former, consider again E.O. Wilson, an apparent deist, who weds belief in God with one of the most robust defenses of scientism from the last few decades. On the other end, there is no shortage of atheists who reject scientism. Here I’ll note the interesting example of respected analytic philosopher (and atheist) Laurence BonJour. In his book In Defense of Pure Reason, BonJour offers an extended defense of what philosophers call synthetic a priori knowledge. While scientism is empiricist in nature, synthetic a priori knowledge is rational and intuitive as it promises an immediate grasp of the world of concrete reality and abstract possibility through reason alone. To be sure, BonJour does not dispute that empirical study provides one essential source of knowledge about the world. But his point is that one can also gain knowledge through rational intuition and BonJour develops powerful and nuanced arguments in defense of his case. My point here is not to assess the adequacy of BonJour’s arguments. Instead, it is sufficient to note that BonJour is an atheist who explicitly rejects scientism. Consequently, one should not equate atheism and scientism or suggest that there is an entailment relation between them.

Wilson, Consilience, 3.

Sellars, Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind, (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 83.

Cited in Conor Cunningham, Darwin’s Pious Idea: Why the Ultra-Darwinists and Creationists Both Get it Wrong (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2010), 266. Paul Moser and David Yandell “every legitimate method of acquiring knowledge consists of or is grounded in the hypothetically completed methods of the empirical sciences (that is, in natural methods).” “Farewell to Philosophical Naturalism,” in Naturalism: A Critical Analysis ( ), 9.

Stenger, The New Atheism: Taking a Stand for Science and Reason (), 13.

Stenger, The New Atheism: Taking a Stand for Science and Reason,13.

Stenger, The New Atheism: Taking a Stand for Science and Reason, 160. He also adds materialism.

In Defense of Pure Reason (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

For more on scientism see Richard N. Williams and Daniel N. Robinson, eds. Scientism: The New Orthodoxy (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

The post Do atheists worship science? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 2, 2020

One of the most profound statements I ever heard on race and racism came from a game show host

The post One of the most profound statements I ever heard on race and racism came from a game show host appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 1, 2020

Canadian Christians & Skeptics vs. American Christians & Skeptics: My Annual Anti-Malaria Fundraiser!

Well, this is the highlight of the year for my website: it is time, again, for my annual fundraiser for the Against Malaria Foundation, one of the most efficient and impactful charities in the world! This year, I made a video (featured below) with an interview with Rob Mather, the founder, and CEO of the Against Malaria Foundation. Mather is a true world changer and someone I greatly admire and I was honored that he took the time for a conversation.

Well, this is the highlight of the year for my website: it is time, again, for my annual fundraiser for the Against Malaria Foundation, one of the most efficient and impactful charities in the world! This year, I made a video (featured below) with an interview with Rob Mather, the founder, and CEO of the Against Malaria Foundation. Mather is a true world changer and someone I greatly admire and I was honored that he took the time for a conversation.

So here’s the contest. Between now and Christmas eve, we have two teams: America and Canada. In each case, I am inviting Christians and skeptics of each country to join together and show that they truly are the most generous in fighting malaria. And remember, all donations receive a tax receipt in Canada or the United States.

American Christians & Skeptics vs. Canadian Christians & Skeptics fighting malaria. Who is more generous? You decide!

And since I believe in putting my money where my mouth is, I have kicked things off by donating $1000 to the Canadian fund. So come on friends, join the contest and change the world!

To donate to the American fundraiser, click here: https://www.AgainstMalaria.com/Americ…

To donate to the Canadian fundraiser, click here: https://www.AgainstMalaria.com/Canadi…

The post Canadian Christians & Skeptics vs. American Christians & Skeptics: My Annual Anti-Malaria Fundraiser! appeared first on Randal Rauser.

November 28, 2020

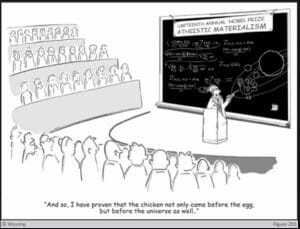

Atheism and Materialism: Are They the Same Thing?

This is the second article in my new series exploring the relationship between atheism and various other commonly associated ideas. In the first article, I explore the link between atheism and skepticism. In this article, we look at the relationship between atheism and materialism.

This is the second article in my new series exploring the relationship between atheism and various other commonly associated ideas. In the first article, I explore the link between atheism and skepticism. In this article, we look at the relationship between atheism and materialism.

What is the relationship between atheism and the philosophy of materialism? The close association between atheism and materialism is evident in Christopher Hitchens’ edited volume The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever which includes as its first entry a collection of excerpts from the great Roman philosopher Lucretius’ magisterial two thousand-year-old poetic work De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things). This famous poem provides a sweeping depiction of the ancient Greek materialist’s vision of reality. Lucretius begins,

For ‘tis high lore of heaven and of gods that I shall endeavour

Clearly to speak as I tell of the primary atoms of matter

Out of which Nature forms things: ‘tis “things” she increases and fosters;

Then back to atoms again she resolves them and makes them to vanish.

Later he adds the following bucolic vision:

Secondly, why do we see spring flowers, see golden grain waving

Ripe in the sun, see grape clusters swell at the urge of the autumn,

If not because when, in their own time, the fixed seeds of matter

Have coalesced, then each creation comes forth into full view….

With these two elevated poetic passages, Lucretius is painting for us a picture of the world in the terms of the Greek atomists, a world in which all the things we encounter from blooming flowers to fulsome golden heads of grain are borne of the atoms that make up all things. As nineteenth-century poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley described it in the poem “Hellas,”

Worlds on worlds are rolling over

Like creation to decay

Like bubbles on a river

Sparkling, bursting, borne away.

In one sense, Lucretius’ materialist vision of nature being wholly composed of atoms is striking for its marginalization of spirit forces and in that sense it appears to offer the kind of secularized and skeptical worldview that warrants its inclusion in a book chronicling the intellectual atheist tradition.

More about that aspect anon, but note first that the passage in question is not explicitly atheistic. Indeed, the first passage begins with a reference to “the gods.” Granted, deity has little-to-no religious function in Lucretius’ atomistic vision of reality. But even so, one cannot dismiss the reference as if it is merely perfunctory. The fact remains that deity is not eliminated altogether from Lucretius’ worldview, even if the realm of the gods is placed beyond the horizon of existential relevance.

Lucretius did not originate the tradition he represents. He was a disciple of Epicurus who in turn drew his philosophical inspiration from the Greek atomist Democritus. In his magisterial History of Western Philosophy Bertrand Russell (perhaps the most important atheist of the twentieth century) expressed his view that the Greek atomists like Democritus provided a striking anticipation of contemporary science:

“Their point of view was remarkably like that of modern science and avoided most of the faults to which Greek speculation was prone. They believed that everything is composed of atoms, which are physically, but not geometrically, indivisible; that between the atoms there is empty space; that atoms are indestructible; that they have always been, and always will be, in motion; that there is an infinite number of atoms, and even of kinds of atoms, the differences being as regards shape and size.”

The atomists had their internal disagreements regarding issues like the precise nature and movement of the atoms (which they believed to be the fundamental constituents of reality), but they shared a commitment to determinism in which all events were governed by natural laws. In Russell’s estimation, “The theory of the atomists, in fact, was more nearly that of modern science than any other theory propounded in antiquity.”

My concern here is not with the accuracy of Russell’s description of Greek atomism or the degree to which the atomists may have anticipated a contemporary scientific view of the world. (However, while we’re on the topic, it should be said that the deterministic world of Greek atomism looks like a more natural fit with pre-Einsteinian science than the world of quantum and chaotic indeterminacy that is the current picture in science. ) Rather, my point is that modern atheists like Hitchens and Russell see a close association between their own atheism and a materialist tradition that extends back more than two millennia.

Naturalism and Physicalism

It is important to recognize that while Greek atomism may seem dated, materialism itself is not a relic of the past. In fact, it lives on even now within the academy, although these days one is more likely to find it identified under a label like naturalism or physicalism.

The definition of naturalism is much disputed. Or perhaps a better way to put it is that there are distinct concepts at play that share the same name. In some instances, naturalism refers to the view that nothing exists beyond nature and that nature is a closed system. Others define naturalism explicitly in terms of the end goals of science, i.e. as the view that whatever exists is that which will one day be defined by a completed natural science. Under this guise, naturalism merges with another concept, scientism, which we will discuss momentarily.

Fortunately, the term physicalism is easier to define. Daniel Stoljar states that “Physicalism is the thesis that everything is physical, or as contemporary philosophers sometimes put it, that everything supervenes on the physical.” Clearly, there is significant overlap between classic materialism and contemporary naturalism and physicalism. All these views affirm that existence is somehow to be understood in terms of nature and natural science.

Reductive and Non-Reductive Materialism

Let’s hone in for a moment on one aspect of Stoljar’s definition, namely the reference to non-physical entities supervening on the physical. Just what is this supervenience relationship exactly? To answer that question, we can begin with the fact that many forms of classic materialism are reductive. That is, they aim to reduce all existence to the material. To illustrate, think of the world as akin to a photograph of a crowded summer beach with hot sand, rolling surf, puffy clouds on the horizon, and hundreds of umbrellas, beach balls, towels, and swimmers. Now move in closer and focus on a portion of the photograph. As you continue to focus in, eventually the particulars of the image disappear as the scene blurs into patterns of tiny pixels, each one composed of a red, green, and blue element. Just as the image of the photograph is reducible to the pixels, so, in this reductive picture, the world around us with all its diversity and complexity is reducible to fundamental physical constituents, atoms in the classic Greek picture. Reductive materialists believe something like that is true of the universe. Even something as seemingly irreducible as consciousness, composed as it is of intentional thoughts, sensations, and emotions, is nonetheless believed to be reducible to material constituents much like the picture is reduced to pixels.

While some philosophers still accept the reductive picture, others believe that various aspects of reality and consciousness, in particular, are not reducible to physical constituents in the way the picture is reducible to the pixels that compose it. Instead, they insist that reality is complex and layered, with novel, irreducible ontological realities emerging at higher levels of complexity. John Heil writes, “We inhabit a layered world, the characteristics of which present a hierarchical or sedimented appearance.” And that brings us to the concept of supervenience. For many philosophers, the mind-brain relationship has provided the paradigm example of a supervenience relation. Thus, for example, the idea is that physical neurons firing in the (physical) brain give rise to non-physical conscious experience (e.g. tasting spearmint). In that case, the conscious experience of tasting peppermint supervenes on the physical pattern of neuron synapses in something like the way smoke supervenes on a fire. The sensation of tasting peppermint cannot be reduced to the neurons firing in the way the image is reducible to pixels. Nonetheless, the sensation is dependent on the physical pattern of neurons firing.

While the mind/brain relation provides the paradigm example of a supervenience relation, there are many others as well. To note one further example, the property of liquidity supervenes on the molecular structure of hydrogen and oxygen atoms as they comprise H20. In other words, when hydrogen and oxygen atoms combine to form water, the novel property of liquidity supervenes on those atoms. The property of liquidity is a necessary byproduct of the existence of water. Physicalists believe that in a similar way the creation of a brain with collections of firing neurons gives rise to a novel by-product: consciousness. Like smoke rising from a fire, consciousness arises from the functioning of a brain.

When is one a materialist?

There is an important difference between reductive and non-reductive materialist models of the world. And that difference leads one to ask, just what does it take to qualify (or fail to qualify) as a member in good standing of this materialist-naturalist-physicalist tradition? That’s a difficult question to answer because traditions like this inevitably have fuzzy boundaries, and there is no universally recognized magisterium, that is, a teaching authority or a judging panel, to which one may appeal to settle a dispute. Having said that, it seems to me that the materialist tradition can be understood as combining thesis 1 with thesis 2 or thesis 3:

causal closure thesis: the system of nature is closed to intervention by any outside agent/intelligence;

weak materialist thesis: everything that exists in nature is material or supervenient on the material;

strong materialist thesis: everything that exists is material or supervenient on the material.

Can a theist be a materialist?

Having summarized the materialist tradition with these various theses, we can now pause to ask the question of whether theists might qualify as adherents to this materialist tradition. Let’s begin with thesis (1) concerning causal closure. If we turn back to Lucretius we certainly get the picture of nature as a closed system in keeping with the causal closure thesis. At the same time, as I noted, Lucretius allows for the possibility that there are gods beyond this closed natural system. The specific type of theism that affirms God along with a causally closed universe is called deism. According to deism, God brings the universe into existence but he does not engage in discrete action within the universe once it is created.

It is important to recognize that one does not need to go back two thousand years to find an adherent of the naturalist tradition accepting deism. Even today there are naturalists who explicitly take this position. In his book Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge scientist E.O. Wilson provides a dazzling and ambitious defense of a naturalist view of the world. In Wilson’s optimistic view, science may one day achieve a sweeping understanding of a complete closed system of nature ranging from fundamental physics all the way up to the reified reaches of ethics and aesthetics. At the same time, Wilson tentatively retains a place for God (defined in deistic terms) just beyond the border of nature. As he says, “On religion, I lean toward deism but consider its proof largely a problem in astrophysics.” Note that Wilson appears to endorse causal closure.

While we could spend more time exploring the nuances of naturalism and the lineaments of causal closure theism, the lesson for us, as William Dembski rightly observes, is that “Naturalism is not atheism. To affirm that nature is self-sufficient is not to deny God’s existence. God could, after all, have created the world to be self-sufficient.”

Before moving on to the two supplemental materialist theses, it is perhaps worthwhile to point out that some non-deistic theists also accept causal closure. And how might this work? To consider one proposal, Dennis Bielfeldt offers an interesting, if speculative, model in which God supervenes on the material universe and then exercises top-down causation back into it in analogy to human minds acting on human brains. Bielfeldt’s model is clearly intended to offer a way to accept both causal closure and non-deistic divine action in the world. And while the proposal faces significant objections and challenges, one must at least concede that its very existence shows that even non-deistic theists could accept the causal closure of nature. Even if the universe is causally closed, God need not be consigned to existence beyond the outer limits of the cosmos.

Theism, Weak Materialism, and Strong Materialism

Next, let’s consider the relationship between theism and the weak and strong materialist theses. Might one find theists who would support these claims? To begin with, one can find several Christian philosophers of late who have endorsed weak materialism. For example, Nancey Murphy, Professor of Christian Philosophy at Fuller Seminary, has done some important work in developing and defending a non-reductive supervenient model of the world. Non-reductive physicalism (as the view is often known) is actually quite popular today among Christian philosophers and theologians.

Okay, but what about strong materialism? Surely one could not find a theist who is a strong materialist? After all, God is by definition non-physical, is he not? No doubt it is true that mainstream theism is committed to a repudiation of strong materialism. However, that doesn’t change the fact that one can indeed find materialists who are theists. For starters, Mormon theology is built on a materialist metaphysic that construes even the divine being as a material entity. What is more, the great third-century Christian theologian Tertullian was a materialist who conceived of God as a material being. To be sure, Tertullian’s strong materialism is highly idiosyncratic relative to the wider Christian tradition. But idiosyncratic though it may be, the fact remains that it is at least possible for a theist (and even a Christian theist) to be a strong materialist.

To sum up, theism is consistent with the great tradition of materialism as evidenced in the fact that theists can endorse (1) the causal closure thesis, (2) the weak materialist thesis, and (3) the strong materialist thesis.

Atheists Who Reject Materialism

This brings us to another important point. Just as a theist could accept materialism, so an atheist could reject it. And indeed, some high profile, respected atheists do precisely that. This brings us to the case of Thomas Nagel, the University Professor of Philosophy and Law Emeritus at New York University. While Nagel has been outspoken about his own atheism, he is also among the most persistent and effective critics of materialist or naturalist accounts of reality. Nagel provides his critique of naturalism as well as his counter-proposal in his book Mind and Cosmos: Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature is Almost Certainly False. Nagel is driven in particular by the mind/brain problem which he believes presents an irresolvable problem for conventional models of materialism/naturalism. Since he is an atheist, Nagel also repudiates theism. But in his view, there is an unexplored middle territory between theism and naturalism and it is this territory that Nagel stakes out for his own view.

And just what is that territory? Nagel suggests the possibility of a panpsychic view in which consciousness is fundamental and ubiquitous in the cosmos. As he suggests, “Everything, living or not, is constituted from elements having a nature that is both physical and nonphysical—that is, capable of combining into mental wholes. So this reductive account can also be described as a form of panpsychism: all the elements of the physical world are also mental.” In this way, Nagel seeks an explanation for life, consciousness, reason, and knowledge which depends neither on divine action (as in theism) nor as accidental by-products of laws of nature but instead as “an unsurprising if not inevitable consequence of the order that governs the natural world from within.” Nagel recognizes that this proposal is “unorthodox” relative to the naturalist tradition, but he is nonetheless compelled by the evidence as he sees it, to explore this otherwise idiosyncratic position.

Here we find ourselves at the tip of an iceberg of debate. The takeaway point for us is simply that Nagel presents his view precisely as an atheist who is dissatisfied with the prospects of the venerable naturalist tradition that traces back to Lucretius and the Greek atomists. So the irony is that theists may accept and work within the materialist/naturalist tradition while atheists like Nagel explicitly reject it.

Lucretius, “From De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things),” trans. W. Hannaford Brown, in Hitchens, The Portable Atheist, 2.

Lucretius, “From De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things),” 4.

“Hellas,” The Complete Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2009), 325.

Bertrand Russell History of Western Philosophy (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972), 65.

Russell, History of Western Philosophy, 66.

The word atom comes from the Greek work atomos meaning “uncut” or “indivisible.” Since scientists split the atom the journey to understand the most fundamental constituents of material existence from protons, neutrons, and electrons on to more exotic subatomic particles and beyond. This transition calls to mind the old adage, he who marries the science of the age is soon a widower

For further guidance on the definition of naturalism see Kelly James Clark, ed., The Blackwell Companion to Naturalism (Malden, MA: Wiley, 2016); David Papineau, Philosophical Naturalism (Oxford; Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1993); Stewart Goetz and Charles Taliaferro, Naturalism (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008);

For difficulties with this picture see Bas van Fraassen, “ “.

Daniel Stoljar, “Physicalism,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

John Heil, The Nature of True Minds (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 5.

For a further discussion of supervenience see Heil, The Nature of True Minds, chapter 3. Many philosophers have worried that this picture results in the consequence that consciousness is causally inert. In other words, the mind does not do things in the world. See Heil, The Nature of True Minds, chapter 4; cf. David Chalmers, The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 150-60.

E.O. Wilson, Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (New York: Vintage, 1999), 263.

Dembski, “Naturalism and Design,” in William Lane Craig and J.P. Moreland, eds., Naturalism: A Critical Analysis (London: Routledge, 2000), 253.

Bielfeldt, “The Peril and Promise of Supervenience,” in Niels Henrik Gregersen, et. al, eds. The Human Person in Science and Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000), 140-7.

First, his model seems to make God dependent on the existence of the universe. Second, unless Bielfeldt can secure a top-down casual influence from the supervenient entity to the subvenient base, God’s action in the world will be rendered inert.

John Durham Peters writes: “Joseph Smith wrote that spirit was a form of matter, and that God the Father and his Son have tangible bodies of flesh and bone” (D&C, 130, 131).” “Reflections on Mormon Materialism,” Sunstone, 16, no. 4 (March, 1993), 47.

A.H. Armstrong writes, “In spite of his ferocious contempt for the philosophers and for all professed and conscious attempts to adapt Christianity to pagan philosophy he was himself very deeply affected by Stoic thought, and like the Stoics is unable to conceive of any kind of real substantial being which is not body; therefore as God and the soul are undoubtedly real and substantial they must, for Tertullian, be bodies.” An Introduction to Ancient Philosophy (Totowa, NJ: Helix, 1981), 168.

We will encounter him again later in the chapter when we discuss antitheism.

Nagel, Mind and Cosmos (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/physicalism/ (Accessed June 25, 2016).

“I do not find theism any more credible than materialism as a comprehensive world view. My interest is in the territory between them.” Nagel, Mind and Cosmos, 22.

Nagel, Mind and Cosmos, 57.

Nagel, Mind and Cosmos, 32.

Nagel, Mind and Cosmos, x. Also see Joseph Brean, “‘What has gotten into Thomas Nagel?’: Leading atheist branded a ‘heretic’ for daring to question Darwinism,” in National Post (March 23, 2013), http://news.nationalpost.com/holy-post/what-has-gotten-into-thomas-nagel-leading-atheist-branded-a-heretic-for-daring-to-question-darwinism (Accessed July 1, 2016).

The post Atheism and Materialism: Are They the Same Thing? appeared first on Randal Rauser.