Randal Rauser's Blog, page 163

January 1, 2016

The Humanist Chaplain: A Response to the Bart Campolo / Friendly Atheist Interview

You may recall that back in 2014 Tony Campolo’s son Bart made news because he was serving as a humanist chaplain at the University of Southern California. This is news first because Tony is evangelical royalty: a prolific Christian author, public speaker, and preacher. It’s doubly news because his son Bart (who is now in his early 50s) was apparently a Christian minister and speaker much in demand himself. So when it turns out that a long time minister and son of one of the most beloved of Christian leaders in the world is now an atheist (though Bart prefers the term “humanist”), that gets people’s attention.

While I had read an article or two on Bart’s story back in 2014, I had never followed up on it in any depth. So I was intrigued when I discovered that Hemant Mehta had interviewed him on a July 2015 episode of The Friendly Atheist Podcast. Now having listened to the episode, I can say that it was a great discussion. Bart is a very capable speaker (in this case the old adage is true: the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree).

The first thing I appreciated was Bart’s irenicism and positivity. As he noted in the interview, he was invited to provide pastoral care to secular students on USC campus. Bart recounted that there are about 100 student groups devoted to the spiritual needs of various religious communities on campus, but none serving the vast secular student body. When it comes to pastoral care, the typical angry new atheist is a poor fit. Bart, however, retains a great deal of respect for his evangelical background. Indeed, he is happy to describe himself as “religious”, whilst defining the term (quite plausibly, I might add) as consisting of a concern with life’s biggest questions. Consequently, Bart carries none of that asinine “us vs. them” thinking that is so common in the popular skeptical/atheist/humanist movement.

In fact, Bart notes that when a Christian student comes to him wrestling with some matter of faith, if Bart perceives a “small fix” is required, he’ll help that student through the problem, thereby leaving him/her with a stronger Christian faith. This good will gesture is borne of Bart’s perception that Christianity can bring a lot of good in the world, so there is no need to shatter the faith of those who are doing well as Christians.

I also appreciated Bart’s insistence that atheists/secularists/humanists need to become better storytellers. That is, they need to become more adept at presenting their belief system in a winsome manner. Bart knows well that the typical atheist storyteller is terribly bleak. Consider this oft quoted passage from Bertrand Russell’s essay “A Free Man’s Worship”:

That Man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins–all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand. Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built.

Atheists like Russell seemed to relish stating their view of life in the starkest, bleakest terms, perhaps to highlight their iron constitutions, willing to face the meaningless of their own existence.

But this doesn’t work well for chaplains who are attempting to comfort people in the face of loss and encourage the grieving, the depressed, and the dissolute that this life really is worth living. It’s also mighty thin gruel for those simply concerned with the question “What ought I to do with my life?”

Enter Bart the humanist chaplain who tells the story differently. His approach is first to emphasize the beauty and goodness of existence itself. If you win the lottery, he says, the proper response isn’t to complain that you didn’t win more. And merely by existing we’ve won a lottery of sorts. To complain that we don’t have more is poor form. Let’s be thankful for the life we do have.

Thus far we have a cup-is-half-full apologetic for the fulfilled humanist life. But Bart also goes on offense by charging that belief in eternal life devalues the life we have now. In short, Bart appears to be appealing to a principle of scarcity value, the principle that the value of a resource is linked to its relative availability/scarcity. Think how the stipulation for a limited time only tends to increase the perceived value of something. All the more so, Bart opines, if that limited time is our seventy or eighty year life spans.

By this reasoning, if human life goes on forever then it is less valuable. In other words, we would value it less. The fact that it is finite and comparatively brief enriches the life we live. So says Bart.

So what should we think of Bart’s claim? Is life to be valued more greatly if it is finite in duration? There are many problems with this claim. But I’ll just note three here.

First, let’s grant for the sake of argument that life is more valuable if it is scarce. So long as this is understood appropriately, I don’t think it presents any problem to the Christian. How so? All we need to do is shift our gaze from life as the sum total collection of lived moments to those lived moments that comprise the set. You see, even if the set is infinite, the moments that constitute that set are finite, and that means unique, irreplaceable, and thereby scarce.

Consider, for example, the moments that constitute aging. At present my daughter is a teenager. Her days as a toddler and small child are lost forever, even set against the backdrop of eternity (though for another possibility see my book What on Earth Do We Know About Heaven?). Her teen years are likewise fleeting and will also soon be gone. The life we have now as a family, the memories we create with one another, with friends, with the community in which we live, are all soon gone. The two years my wife and I spent living in London, England are now long in the past. The years I spent growing up in Kelowna, BC are a receding memory.

But doesn’t it follow that in eternity we will inevitably fall into a rut in which deja vu takes over as we’ve done everything countless times before? Nah. As a remedy for that errant conclusion, I suggest Bart read (or reread) the ending to C.S. Lewis’ The Last Battle where the repeated refrain is further up and further in, a never-ending journey of new discovery and growing excitement.

Thus, even if our life continues into eternity, the particular moments that make up that life now are still disappearing. And that grants the individual, finite, irreplaceable moments in a journey that meet Bart’s demand for a scarcity value.

Second, while Bart claims that the finitude of life enriches the value of that life, I would counter that it can also erode the joy of life and with it the value of that life. My claim is well attested. For example, in my article “Life is a concentration camp, so why are you smiling?” I discuss Woody Allen’s interview in the American Masters series in which he describes coming to terms with his own mortality at about the age of five. This realization left Allen with a melancholy streak that has come to define his experience of life. He says,

“And that thought over the years took different forms. As I later got older and always used my concentration camp example of people around me having fun, enjoying themselves, and I want to say to them ‘Don’t you realize you’re going to go up in a smokestack you know, in a short while? So why are you so happy? Doesn’t that thought sort of put a damper on things?

“We all know the same truth and our lives consist in how we choose to distort it.”

It seems to me very plausible to conclude that Allen values his life less because of its absurdist brevity. And countless people — atheists and theists — have shared Allen’s conclusion. Consequently, for many the belief in human finitude leads them to value their life less rather than more.

Finally, let’s consider Bart’s provocative claim that human existence would not be meaningful if it went on forever. Here I must say it is quite disappointing to find somebody who was raised in the church and pastored for thirty years demonstrating such a disappointing lack of imagination regarding life in a reconciled and restored creation. C.S. Lewis once wrote of “an ignorant child who wants to go on making mud pies in a slum because he cannot imagine what is meant by the offer of a holiday at the sea.” While intending no disrespect to Bart, when skeptics opine that an eternity with God in a restored creation would surely get tiresome after awhile, I can’t help but think of that child whose lack of imagination leaves him satisfied with mud pies … and suspicious of beaches.

It should not be surprising that I am unpersuaded by Bart’s account of meaning. At the same time, I do think he is an outstanding communicator who has identified a real weakness in the skeptical/atheist movement. And his humanist brand of atheism is orders of magnitude more winsome than the caustic, condescending, reductionist anti-religious fundamentalism that has been in vogue since the new atheists took the spotlight. Moreover, I admire his desire to attend to the spiritual needs of a large constituency, even if I consider the resources he has to draw upon to be tragically impoverished.

You can find Bart online at http://bartcampolo.org/.

December 30, 2015

The Meaning of Life: A New Year’s Eve Reflection

The dawning of a new year is a great opportunity for a little life reflection. But this New Year’s Eve, don’t stop with the standard resolutions (e.g. lose weight!; spend more time with family!; read more books!). Dig a little deeper by considering the question of meaning.

The dawning of a new year is a great opportunity for a little life reflection. But this New Year’s Eve, don’t stop with the standard resolutions (e.g. lose weight!; spend more time with family!; read more books!). Dig a little deeper by considering the question of meaning.

A little while ago I was reading an essay in which an atheist claimed that human lives are meaningful insofar as they have projects. Unfortunately, he never offered a moral framework to evaluate the kind of projects we pursue.

As a result, Smith could adopt the project of perpetuating racial segregation and Jones could adopt the project of becoming extremely wealthy. And the projects of Smith and Jones would thereby render their lives meaningful as surely as Malala Yousafzai’s project of fighting for global justice and equity would render her life meaningful. But that can’t be right. Meaning is not merely a personal preoccupation: it’s a pursuit of a lasting good.

So ask yourself first: does my view of the world provide an account of meaning? And does it provide an account that allows one to judge lives meaningful not merely with respect to personal projects but also with respect to the objective value or worth of the projects pursued?

One more thing: projects may be personally fulfilling and good without being transcendently significant, without having that lasting good that I referred to above. But the question of meaning, so it seems to me, is one that is most satisfactorily answered with respect to accounts of meaning that offer not merely personal fulfillment but transcendent significance and lasting good.

A few weeks ago I was killing time at a sports complex waiting to pick up my daughter. I had found a little alcove to sit and work on my computer, nestled right beside a largely forgotten trophy case with aging trophies covered in a layer of dust. Ensconsed there in my alcove, I mused on the fact that these trophies represented triumphant sports performances of thirty, forty, and fifty years ago, few of which were of any significance to people today. In short the various projects that crowded the trophy case may have yielded temporary personal fulfillment. But now, largely forgotten and covered with a layer of dust, they offered no transcendent significance and little-to-no lasting good.

As you look to the new year, ask yourself if your view of the world yields an account of meaning that offers personal fulfillment, an objective value assessment, and transcendent significance that produces lasting good.

If it doesn’t, might I suggest that you keep looking?

December 29, 2015

You now have permission to admit The Force Awakens is lame

Please note: there are no spoilers in this article, except for the observation that J.J. Abrams spoiled a great opportunity.

Please note: there are no spoilers in this article, except for the observation that J.J. Abrams spoiled a great opportunity.

I walked out of Star Wars: The Force Awakens thinking, “Was it just me?” After all, the film had stellar critical reviews, an outstanding 8.6 user rating on IMDB, and record-setting box office. Granted, there was that one Grinch reviewer from the Vatican who didn’t like it. But hey, asking some aging priests to rate the latest Hollywood blockbuster is like asking grandpa to rate the latest AC/DC album. (On second thought, a large portion of AC/DC’s fan base are grandpas. Anyway, you know what I mean.)

And yet, when I talked to one of my friends who’d seen the movie he shrugged his shoulders with a “meh”. Since then, I’ve found about one third of the people I’ve talked to have guardedly expressed disappointment with the latest installment. So it wasn’t just me. Others found the film perfunctory, unimaginative, and consisting of a slavish adhering to A New Hope‘s plotline. Not even a droid ball could save this one.

But still, my concerns were burbling on the backburner. After all, other people I asked would immediately overwhelm my tepid question with gushing “I loved it!” And that would be just enough to lead me to question my misgivings once again.

Then I read Michael Hiltzik’s column in the LA Times titled “Admit it: ‘Star Wars: The Force Awakens’ stinks — and here’s why“, and it blew my concerns wide open.

Hiltzik begins by observing that the film “reproduces George Lucas’ original 1977 movie slavishly almost to the point of plagiarism.” He then adds,

“This isn’t to say that it’s not an enjoyable way to spend a couple of hours. If you’re among the millions who plainly have done so, bless your heart. The issue, however, is whether “The Force Awakens” even deserves to be considered as a movie, because it’s not. It’s the anchoring element of a vast commercial program, painstakingly factory-made for maximal audience appeal, which means maximal inoffensiveness. The result tells us a lot about the state of entertainment today, and about the future of Hollywood.”

Why am I surprised? In the lead up to the film I kept hearing ad nauseam about how Disney paid $4 billion for the franchise and were determined to “recoup their investment”. Well, it is now clear that they will do that and more power to them. But the resulting product is about as lifeless as a loaf of Wonderbread.

There are good reasons why The Force Awakens has been received so well and they pertain to cognitive biases like the contrast effect (it certainly is far better than the immediately preceding three installments), expectation bias (people had understandably high hopes that Abrams would succeed) and the bandwagon effect (everybody loves it!).

Biases aside, for a large portion of the audience (myself included) there is a powerful nostalgia with seeing the Han Solo, Luke Skywalker, and Princess Leia once again. But after watching The Force Awakens I must admit that the real Star Wars films, the ones of my youth, are now a long time ago, and far, far away.

December 28, 2015

80. The Problem with Porn: A conversation with Matt Fradd

Randal Rauser chillin’ with Matt Fradd

We live in a world where Abercrombie and Fitch sell padded bras for eight year olds, where b-movie stars build their careers by tweeting demeaning selfies to their legions of voyeuristic knuckle dragging fans, and where an adjective like “sexy” is now used to describe everything from sports cars to sermon titles. In short, ours is a culture increasingly saturated with sexual obsession.

The year 2015 did see one superficially promising shift as Playboy Magazine, that cultural stronghold of porn since the 1950s, announced that they would no longer be printing pictures of naked women. Alas, the decision arose not from a new sense of social responsibility, but rather from the sheer market saturation of free titillation available on the internet.

And while men remain 543% more likely to look at pornography than women, a tale like 50 Shades of Grey can now top both the box office and the bestseller lists driven by an exploding market of sexually disinhibited women. And when they’re done with the book and film, they can turn to their Tinder app for a no-strings attached hookup.

Given a climate like this, it should be no surprise that pornography has gone mainstream as traditional sexual mores have evaporated like dew in the piercing rays of a sexually liberated dawn.

Sadly, things are not much better in the church. For example, one 2014 survey on pornography sponsored by Proven Men Ministries and conducted by the Barna Group revealed that 64% of 31-49 year old Christian men look at pornography at least once a month. Even worse, 36% of Christian 18-30 year olds look at pornography at least once a day. Another survey reports that upwards of 20% of Christian women are addicted to porn.

I’d say it’s time to say a bit more about this sexual epidemic, And so in this episode of The Tentative Apologist Podcast we are going to take a step back to reflect on the nature of pornography, the extent of the problem it presents, and to consider some advice on how a Christian should respond to it. To help us answer these questions I’ve enlisted the aid of my friend, Catholic apologist Matt Fradd. Matt heads a popular ministry called The Porn Effect which states as its mission, “To expose the reality behind the fantasy of pornography and to equip individuals to find freedom from it.” Amen to that!

Matt speaks around the world on the topic and has a book forthcoming on pornography in 2017 with Ignatius Press. He’s also written several articles on the topic including these four articles dealing with porn and marriage, sexual violence, erectile dysfunction, and the brain.

In the midst of ministry and writing, Matt also finds time to be a family man. He’s married to Cameron and together they are raising four children in north Georgia. You can visit Matt online at mattfradd.com.

Also, check out Matt’s video on “The Great Porn Experiment”.

December 27, 2015

Making a Murderer: A Review

Imagine being convicted for a crime you didn’t commit, the horrid crime of a violent assault and attempted rape. And then imagine going to prison for 18 years for that crime. And then imagine that you are finally exonerated of the crime after DNA establishes your innocence. And then further evidence comes to light that evidence for your innocence was suppressed by the prosecution, an egregious case of legal (and moral) misconduct.

Imagine being convicted for a crime you didn’t commit, the horrid crime of a violent assault and attempted rape. And then imagine going to prison for 18 years for that crime. And then imagine that you are finally exonerated of the crime after DNA establishes your innocence. And then further evidence comes to light that evidence for your innocence was suppressed by the prosecution, an egregious case of legal (and moral) misconduct.

Finally, after all that suffering and injustice, you now become a poster child for the wrongfully accused, and a symbol of the broken policing and judicial systems. You’ve now launched a lawsuit seeking damages, and with widespread public support folks are suggesting that you could receive a payout north of $30 million. You’ve got a new girlfriend. Your family are no longer social pariahs. Life is good.

Then a young woman disappears and is found dead days later. The wheels of that same broken policing and judicial system that convicted you twenty years before begin to lurch into motion again. And before you know it, the unthinkable has occurred: you are now accused of murder.

Be glad it’s not you. But it is Steven Avery, likely the most unlucky man in all Wisconsin. And that story such as I’ve told it is merely the opening act in a new ten hour documentary which just began streaming on Netflix on December 18th.

Yes, ten hours (mercifully in ten installments of approximately 1 hour each). My usual diet of crime, forensic science and criminal trials consist in 22 minute episodes of Forensic Files that I record on my PVR. You see, I’ve got a short attention span and consequently that’s typically about all I can handle. So you might have thought Making a Murderer would be a stretch.

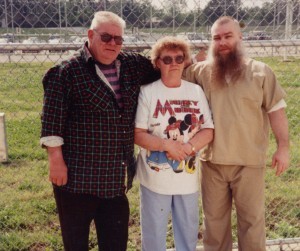

However, I was riveted by the immersion storytelling of this series. (One night we stayed up until 3 am watching episodes in an emotionally exhausting binge session.) Over ten hours you get to know Steven Avery, his nephew Brendan Dassey (who is a co-accused in the murder), and the Avery family. And you share their anger, pathos, and disappointment, not to mention the all-too-rare moments of hope and vindication.

Steven’s two main attorneys, Dean Strang and Jerry Buting, emerge as quiet heroes that demonstrate the inestimable value (and painful limitations) of a capable defense. By contrast, the prosecutor Ken Kratz is a truly deplorable character. And I cannot put into words my distaste for Len Kachinsky, the first defense attorney for Steven’s fifteen year old nephew Brendan. Kachinsky’s grossly unethical behavior seals the boy’s fate and renders him perhaps the most repulsive character of them all. As for the police of Manitowoc county, let me just say that “Wisconsin’s finest” is not a phrase you’ll hear in this series.

Steven Avery with his parents

The series unfolds against the cold grey Wisconsin sky as the filmmakers shift deftly between courtrooms, run down mobile homes, and the seemingly endless rusting wrecks at the Averys’ salvage yard. Complemented by an unforgettably morose, plodding score that sounds like a funeral dirge for lives lost and Lady Justice foiled, the cinematic qualities elevate the mundane to the level of Shakespearean tragedy.

Making a Murderer left me deeply unsettled, somewhat deflated, and with a new respect for the power of the documentary to tell a story … and perhaps to effect change.

December 24, 2015

How young was the Virgin Mary … and was that too young?

I’ve posted some more-or-less heart-warming Christmas greetings in years’ past. See 2014, 2013, 2012, and 2011. This year I’m going to instead offer a brief word on the Virgin Mary. If not particularly heart-warming, hopefully it is at least thought-provoking. And if honest about the problems it raises, hopefully it is not impious for doing so.

I’ve posted some more-or-less heart-warming Christmas greetings in years’ past. See 2014, 2013, 2012, and 2011. This year I’m going to instead offer a brief word on the Virgin Mary. If not particularly heart-warming, hopefully it is at least thought-provoking. And if honest about the problems it raises, hopefully it is not impious for doing so.

Let’s start here: Your standard children’s Christmas play features 12 and 13 year old kids playing out the roles of shepherds, kings, Joseph, and Mary. But of course, we know the shepherds, kings, and Joseph were not 12 or 13.

Mary, however, is a different story. It is common to depict Mary in religious iconography as a young woman in her late teens or early twenties. This seems very unlikely. The 2006 film The Nativity Story is closer to being accurate as Mary is played by then 16 year old actress Keisha Castle-Hughes. But that also doesn’t seem to get it quite right.

Our best guide to the likely age of Mary during the conception, gestation and birth of Jesus is (not surprisingly) the average age of girls at betrothal and marriage. And the typical age for betrothal and marriage in first century Judaism was 12-13. Nor is Israel unique in this regard: ancient Roman practice appears to have followed a similar standard. So it seems quite likely that Mary was 12 or 13 years old at her betrothal to Joseph. In other words, the young actress playing Mary at the Christmas play is spot on as regards her likely age.

There is no doubt that current practices on child marriage place the contemporary reader at some significant distance from the biblical nativity story. UNICEF defines “child marriage” as a formal or informal matrimonial union that occurs prior to the age of 18. Wikipedia has an interesting article on marriageable age in history down to today. While current practices are diverse, on the whole one does find, however, a significant difference overall between the ancient world and today. In our age the vast majority of countries limit marriage as an independent choice of the individual to 18 (or older). Countries allow child marriage under various conditions such as parental and/or court approval. However, only a tiny minority extend that permission to girls as young as 12-13: Trinidad and Tobego allows marriage of females at 12 with parental consent; Iran allows marriage of females at 13 with court approval; Syria allows child marriage at 13.

In sum, today, there is a broad consensus that child marriage is suboptimal at best, and an egregious violation of human rights at worse. The organization Girls not Brides proclaims on its website: “Every year 15 million girls are married as children, denied their rights to health, education and opportunity, and robbed of their childhood.

To be sure, some of the problems with child marriage are culturally relative. For example, it is possible that in some cultures early marriage provides social goods (e.g. protection; new economic opportunity) not otherwise available to an unmarried child of that age. But other problems with the practice are intrinsic. It is widely recognized that 12-13 year old girls simply lack the emotional and cognitive maturity that prepares them to enter into a lifelong covenant. And the fact that the society in question doesn’t recognize the importance of childhood and the gradual nature of cognitive and emotional maturation doesn’t change the fact that they were, as Girls not Brides declares, “robbed of their childhood.”

At this point we can note that there is some parallel between marriage and war. Earlier this year I watched the outstanding (and extraordinarily harrowing) film Beasts of No Nation, an unforgettable dramatic presentation of child soldiers. While children have fought in wars for centuries, we can all agree that the practice is unacceptable and should be eliminated. War is not appropriate for children. There is a similar consensus that marriage is not appropriate for children.

The picture gets even more complicated when we shift from child marriage to child pregnancy and childbirth. In their article “Adolescent Pregnancy: Where Do We Start?” Linda Bloom and Arlene Escuro outline the multiple physical and emotional complications with teen pregnancy (Handbook of Nutrition and Pregnancy, ed. Carol J. Lammi-Keefe, et al (Humana Press, 2008, 101-114).

So where does all this leave us when it comes to Mary? The short answer is, conflicted. One could prefer to believe that contrary to the norm Mary was significantly older than the standard 12-13 when she was betrothed to Joseph. Or one could accept Mary’s likely age and explain it as a divine accommodation to suboptimal ancient practices. You might add that Mary was uniquely mature emotionally, physically and spiritually to take on this unique blessed mission. Finally, you might point out that God as creator and sustainer of all is surely within his rights to act as he sees fit for the redemption of humanity.

You might say all these things. And you might be right to say them. But the story still remains awkward relative to currently accepted practice. So at the very least we might do well to acknowledge that awkwardness.

Er, Merry Christmas?

December 21, 2015

Should you risk your children getting malaria … or affluenza?

In my most recent podcast, “Bringing the Gospel to the poorest nation on earth,” I interview Dr. Roger Chen, a missionary who works in Niger. Roger and his wife have two young children, and this prompted Ed Babinski to post the following comment:

“When does missionary work also become child endangerment? It seems Dr. Chen may be endangering the health and or well being of his wife and children.

“Doctors Without Borders don’t bring their wife and kids along.”

One point I should have made is to note that Mira Chen also works in Niger as an optometrist. So the question can be narrowed in the present case to two professionals serving in a developing nation and bringing their children in tow. That said, I nonetheless made the following reply:

“Let’s say that a brilliant young teacher foregoes job offers at lucrative prep schools to work at an inner city school in Detroit. Would you censure him for preventing his own children from having particular opportunities because of his desire to help the poor?”

Babinski offered another reply which included a restatement of the original question:

“WHEN, or AT WHAT POINT might not missionary work become child endangerment?”

This time around I decided to turn my response into a stand-alone article. And so, here we are.

Now on to my response. Babinski is clear on one risk, i.e. that which occurs from moving to a developing nation. Thus, he is concerned with risks like this:

Risk 1: Raising a child in Niamey, Niger, where they risk contracting malaria.

And that is a risk not to be taken lightly.

But let us not think raising our children in the developed world is without risk. For there are risks, some of them of which you may not even be aware. Like this:

Risk 2: Raise a child in Beverley Hills, California, where they risk contracting affluenza

Affluenza is a serious affliction, one which corrupts the mind into thinking the acquisition and consumption of material goods is existentially important for a fulfilled life. Those stricken with affluenza find shopping to be a leisure activity and structure their lives around the car they drive (BMW), the clothing they wear (Armani; Lululemon), the coffee they drink (Starbucks), and so on.

So which is worse? Would you rather put your child’s body at risk of contracting malaria or their soul at risk of contracting affluenza?

December 20, 2015

Do Christians and Muslims Worship the Same God? A Question Explored Through Sheep and Goats

It’s been about a week since Wheaton College political science professor Larycia Hawkins was launched into the spotlight after she was suspended by Wheaton College, in part because she declared:

“I stand in religious solidarity with Muslims because they, like me, a Christian, are people of the book. And as Pope Francis stated last week, we worship the same God.”

As a result, Christians have been lining up to debate the question: “Do Christians and Muslims worship the same God?” Frankly, I wish they would begin with another question: “What does it mean to say two people are worshipping the same God?” In fact, it seems to me that folks are assuming a lot when they ask the question, and perhaps some of those assumptions need to be examined more closely.

My own two cent contribution to this debate will consist of a thought experiment based on the lives of two people who lived in Rwanda during the 1994 genocide: Christian pastor Elizaphan Ntakirutimana and Muslim UN soldier Mbaye Diagne.

Rwanda: The Background

Before we consider their cases I will set the context by saying a few words about the genocide itself.

The 1994 Rwandan genocide represents the most efficient genocide in the twentieth century, and virtually all of it was carried out with roving militias brandishing primitive farm implements like scythes and machetes. Over a three month period more than 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were butchered while the international community stood by. The demonically bureaucratic calculus of geopolitics that drove Western complacency was soberly summarized by one US official who brazenly declared that “one American casualty is worth about 85,000 Rwandan dead.” (Cited in Samantha Powers, A Problem from Hell, 381). With no economic interest in the region, western powers were loathe to become involved in the unfolding horrors of this middling African nation.

But if we really want to appreciate the horror of this genocide, we need to move from the abstract realm of statistics to the ground zero of blood, soil, and the groans of the dying. In one case, the executive assistant of Romeo Dallaire (commander of UN forces) arrived too late to save Tutsis hiding in a church run by Polish missionaries. He recalled the anguished scene as follows: ”

When we arrived, I looked at the school across the street, and there were children, I don’t know how many, forty, sixty, eighty children stacked up outside who had all been chopped up with machetes.” (Cited in Powers, A Problem from Hell, 349.)

As unimaginable as that horror is, it is but a proverbial drop of blood in the roiling cascade of close to one million lives cut down.

Elizaphan Ntakirutimana

The Christian and genocide

So how did our Christian and Muslim respond? Let’s begin with the Christian pastor.

Elizaphan Ntakirutimana was a leader in the Seventh Day Adventist Church with impeccable theological and pastoral credentials. In the middle of the genocide, several Tutsi Adventist pastors wrote Ntakirutimana a letter appealing for help that opened with the haunting line: “We wish to inform you that tomorrow we will be killed with our families.” (See Philip Gourevitch’s book of the same title.) With painful understatement and extraordinary diginity, these pastors were begging for help and aid from a fellow Christian. So how did Ntakirutimana respond?

Instead of providing assistance to the Tutsis, Ntakirutimana directed Hutu militias to the Mugonero complex where they were hiding, resulting in a grisly slaughter. Think about that: in the cruelest irony the Christian these saints appealed to for salvation instead became their chief executioner. Although Ntakirutimana managed to avoid prosecution for several years, in 2003 he was finally convicted of the crime of genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

Mbaye Diagne

The Muslim and genocide

At the same time that a number of church leaders like Ntakirutimana either stood by or actively joined the genocide, a few brave souls struggled to save what lives they could. One of those was Mbaye Diagne, a captain from the Senegalese army—and a devout Muslim. Working for UN forces, Diagne repeatedly flouted the orders of his commanding officer to remain within the compound. Instead he ventured out time and again to pick up Tutsis in his Jeep—about five at a time—and transfer them to the relative safety of the compound.

In order to accomplish this extraordinarily brave and selfless feat, Diagne repeatedly bargained his way across dozens of Hutu checkpoints, using little more than cigarettes and his good humor. In this way, he worked tirelessly for several weeks, repeatedly putting his life at risk and saving dozens of lives … until he was finally killed on May 31 from flying shrapnel.

The Decision

Now imagine that you have the choice to go before the throne of God on judgment day clothed either in the life and legacy of Elizaphan Ntakirutimana or that of Mbaye Diagne. Which would you choose?

This article is based on my book You’re Not as Crazy as I Think: Dialogue in a World of Loud Voices and Hardened Opinions (Biblica, 2011).

Upcoming Lecture on “Is the Atheist My Neighbor?”

December 19, 2015

False Analogies or the Fallacy Fallacy?

In my review of Why Brilliant People Believe Nonsense I pointed out that Steve and Cherie Miller included a fascinating chapter in which Steve critiques what he calls the “Fallacy Fallacy”. He explains this fallacy as follows:

“I often read comments on blog posts or articles or Facebook discussions which accuse the writer of committing a specific logical fallacy and thus declaring the argument thoroughly debunked, typically with an air of arrogant finality. While the debunker may feel quite smug, intelligent participants consider him quite sophomoric. In reality, he’s typically failed to even remotely understand the argument, much less apply the fallacy in a way that’s relevant to the discussion.

“Surely this fallacy deserves a proper name and should be listed with other fallacies. Thus I’ll define ‘The Fallacy Fallacy’ as ‘Improperly connecting a fallacy with an argument, so that the argument is errantly presumed to be debunked.’” (172)

The fallacy fallacy illustrates the old adage: “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.” In this case, the person knows just enough of logical fallacies to throw around labels that effectively inoculate themselves (and others) against good reasoning.

I highlighted this chapter in the review because I believe the Millers are on to something important here. In my experience, this misuse of “logical fallacy labelling” is rife on the internet. In particular, I noted that in my experience argumentum ad hominem and argumentum ad populum are the most commonly offended against by the internet troll’s Fallacy Fallacy.

But in this article I want to consider another common example of the Fallacy Fallacy: the false analogy. An argument by analogy begins with the observation that two (or more) entities are alike in some particular respects and concludes that they are also similar in an additional respect. The false analogy fallacy applies when the two (or more) entities are not, in fact, analogous at the relevant point. And the false analogy is an example of the Fallacy Fallacy when the objector errantly labels a legitimate analogy as false.

Consider this simple example from Twitter just this morning. It started when a fellow tweeted that calling religious people delusional was a good conversation starter to interact with those people. I tweeted the following response:

“Calling people delusional is a conversation starter like calling somebody ugly is a pickup line.”

Note that this is a compact argument by analogy. You can unpack it like this:

(1) Perceived insults are ineffective ways to initiate a conversation.

(2) Calling somebody ugly is likely to be perceived as an insult.

(3) Therefore, calling somebody ugly is likely to be an ineffective way to initiate a conversation.

(4) Calling somebody delusional is likely to be perceived as an insult.

(5) Therefore, calling somebody delusional is likely to be an ineffective way to initiate a conversation.

The fellow replied with a tweet in which he told me to “check the definition of delusional one more time please.” While I’m not entirely sure what he meant there, as best I can read him, he was disputing the claim that calling somebody delusional was a relevant analogy to calling somebody ugly.

It is not surprising that the false analogy is often victim of the Fallacy Fallacy precisely because any two things are both similar in innumerable ways and dissimilar in innumerable ways. Consequently, the success of any analogy will be contingent upon like similarity in the relevant ways. Meanwhile, the internet troll can always ignore (or overlook) the relevant points of similarity, and instead highlight irrelevant points of dissimilarity as justification for accusing the argument of a fallacious comparison. All the while, the only fallacy being committed is that of the internet troll who has failed to understand the relevant comparison from the beginning.

Several of the atheist reviewers of God or Godless objected to my analogical arguments in the book with a Fallacy Fallacy by highlighting irrelevant points of disanalogy as a way to reject the legitimate analogy. More generally, I regularly encounter this misbegotten analysis in the blogosphere and, as in the present illustration, within the twittersphere as well.

By the way, you can follow me on Twitter here.