Randal Rauser's Blog, page 154

May 7, 2016

Two Conferences, One Busy Week

As you may have noticed, things have been relatively quiet at The Tentative Apologist for the last few days. There’s a good reason for that. On Wednesday-Thursday I spoke at the National Convention for the Fellowship of Christian Assemblies on the topic of Homosexuality, Trangender and Christianity. On Wednesday night I delivered a plenary address and on Thursday I introduced four workshop sessions. (Here is a quick synopsis of the evening plenary).

Then last night I attended Richard Swinburne’s plenary address at a conference on “Atheism and the Christian Faith” sponsored by the Canadian Centre for Scholarship and the Christian Faith at Concordia University College. Swinburne did a great job summarizing his main inductive argument for God based on simplicity and explanatory power. For those who are familiar with Swinburne’s work from The Existence of God (1979) down to today, there were no new revelations, but it is great to hear a succinct one hour statement of the argument.

The conference continues today with another address from Richard Swinburne as well as an additional plenary from Don Page (you might remember Don as the world-famous physicist that I interviewed on my podcast a couple years ago). In addition, there will be several papers by scholars and students. I will be presenting a paper this afternoon titled “Two Arguments for God’s Existence from the Mathematical Structure of Nature.” That paper is a distillation of one of the chapters of my forthcoming book with Justin Schieber, An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Bar: Talking About God, the Universe, and Everything.

May 2, 2016

The Trump Bible

My friend David Marshall (author and blogger at Christ the Tao) emailed me this morning to let me know he had just published a new book.

David began his email by writing: “Hi, Randal. We don’t seem to often agree on politics, so I thought I’d take advantage of one of those times when I think we do.”

That opening line was a nod to the fact that Donald Drumpf is bringing people together … against Donald Drumpf. David and I do disagree on many issues in politics, but we are united in our opposition to this man.

Here we are a day after Drumpf barked at a rally in Fort Wayne, Indiana that China is “raping” the United States. Drumpf used to say China was “killing” the US. So now it is killing and raping Uncle Sam. Presumably, “dismembering” and “cannibalizing” are not far behind. All this illustrates once again that Donald Drumpf is promising little more than to make America hate again.

And that makes the announcement of David Marshall’s new ebook especially timely. You can purchase “The Trump Bible: Why No Christian Should Vote for Donald Trump at Amazon.com.

The cynic (or realist?) in me suspects that anybody who still plans to vote for Drumpf after the last ten months will not be persuaded by David’s book. But if David convinces just one would-be Drumpf voter to reconsider their support for the neo-fascist, hate mongering, xenophobic, narcissistic, misogynistic carnival barker, it shall be worth it.

April 29, 2016

Gamora, Peter Quill and the Ethics of Human/Alien Romance

Gamora and Peter Quill (and retro headphones).

Guardians of the Galaxy is my favorite Marvel movie, not least because it raises a host of complex moral issues. Like this one: is it morally wrong for a human being (Peter Quill) to enter into a romantic relationship with a humanoid alien (Gamora) when the two individuals appear to be physical and emotional complements?

In movies like Guardians of the Galaxy nobody even questions whether this kind of inter-species romance is immoral. Interesting, however, the vast majority of people who would never think twice about this romantic pairing would be appalled at a romantic relationship between Quill and one of the aliens from the film District 9. This despite the fact that the District 9 aliens are every bit as intelligent as Gamora.

A District 9 alien being evicted in a thinly veiled nod to the evils of apartheid.

It seems that the sole basis for approving Quill’s romance with Gamora whilst condemning his romance with District 9 alien is that the former looks human whilst the latter does not. But that would seem to be an insufficient basis for a diametrically opposed moral evaluation of the two relationships.

Let’s agree that it is ethically wrong for Peter to partner with the District 9 alien. And if we believe mere humanoid appearance is insufficient for a moral distinction, then this might oblige us likewise to reject his relationship with Gamora.

But let’s add to the similarity between Gamora and Quill. While her species evolved independently from human beings, what if her DNA were sufficiently similar to human DNA that a geneticist would believe she was a human with an unusual mutation that gave her green pigmentation in her skin? Would physical + genetic compatibility be sufficient to approve of the Gamora/Quill pairing? If so, then does genetics make the difference?

April 27, 2016

Should we shun Christians that we believe are living an immoral life?

Christians disagree on a range of important ethical issues. Consider, for example, the fact that some Christians accept just war theory and believe that the call to follow Christ can be reconciled with the call to fight and kill state-enemies. Meanwhile other Christians disagree in the strongest terms whilst emphasizing the call to follow Christ entails a radical disavowal of violence, state-based or otherwise. And yet, despite the deep divide, most Christians agree that supporters of just war theory and supporters of pacifism should still break bread together in common Christian fellowship. Despite the deep ethical fissures that divide them, Christ still unites them.

But not all ethical issues are like this. Sometimes Christians take a stand on a moral issue which other Christians believe is so radically counter to the call of scripture and Christian discipleship that they can no longer share common Christian fellowship.

I thought of this the other day as I was listening to a recent address by Reformed Baptist apologist James White who provocatively denounced the pro-gay Metropolitan Community Church as a “church of Satan.” While White didn’t unpack all the implications of that incisive rhetorical barb, I took the main point to be unequivocal: Christians ought not share fellowship with members of the MCC.

One might think that James White is taking his cue from Paul in 1 Corinthians 5 when he addressed a man living in an apparently incestuous relationship: “A man is sleeping with his father’s wife.” (1 Cor. 5:1) Paul’s response is unequivocal. He advocates expulsion and shunning. But his punishment is not limited to this offender. Instead, it encompasses a number of offenses:

9 I wrote to you in my letter not to associate with sexually immoral people— 10 not at all meaning the people of this world who are immoral, or the greedy and swindlers, or idolaters. In that case you would have to leave this world. 11 But now I am writing to you that you must not associate with anyone who claims to be a brother or sister but is sexually immoral or greedy, an idolater or slanderer, a drunkard or swindler. Do not even eat with such people.

12 What business is it of mine to judge those outside the church? Are you not to judge those inside? 13 God will judge those outside. “Expel the wicked person from among you.”

Let’s consider two examples of the Christians Paul argues that we ought to cast out and shun: the “greedy” (or covetous) (Gk. pleonektes) and the “drunkard” (méthysos).

The problem with this advice begins with the fact that Paul never specifies how greedy or how much of a drunkard one would be before they are cast off and shunned from the community. One might assume that Paul is thinking of a particular lack of repentance in the individual. Thus, the person who cavalierly gets smashed every weekend without apology should be cast off. But we might continue to extend grace to the alcoholic who falls off the wagon regularly and then cries out in regret and a call for repentance.

I’m sympathetic to that advice. Though one might surely wish that Paul had qualified his directives in this way. One can only imagine how many tortured habitual offenders have been cast off and shunned over the years in a way that only serves to secure their death spiral to destruction.

But a problem remains even with the qualified advice. The unrepentant drunkard and the repentant drunkard are not two distinct categories. Rather, there exists between the two a spectrum of repentance, rationalization, self-justification, delusion, etc. So how far down the continuum toward unrepentant habitual sinner must one be before they are cast out and shunned?

The problem, in short, is that the offense — unrepentant habitual sinner — is a spectrum but the punishment — cast off and shunned — is all-or-nothing. You don’t punish a moderately repentant habitual offender with a moderate expulsion and shunning. You either shun them or you don’t.

And we haven’t even yet considered how to apply this to greed. After all, who in our modern western churches isn’t rationalization some degree of unrepentant covetous behavior?

All this leaves us with a troubling lack of clarity regarding how to apply Paul’s very practical directive in our Christian communities.

April 24, 2016

Christianity and Islam: A Bold Cup Conversation

Islam is the second largest religion on earth. And these days it is the religion most likely to occupy the headlines. From ISIS and Al-Qaeda to burqas and immigration bans, some worry about a clash of civilizations. But Islam is not simply a religion of political and cultural controversy. It is also increasingly the religion of our neighbors, colleagues, and friends.

So how should we think about Islam?

In this video I join Drake De Long-Farmer, the founder and editor-in-chief of BoldCupofCoffee.com, for a conversation with Christian apologist Andy Bannister. Dr. Bannister has his PhD in Islamic Studies and lectures around the world on the question of Islam and Christianity. And we were delighted to have him share this very important conversation.

April 21, 2016

92. God is everywhere: James Gordon on Divine Omnipresence

Dr. James Gordon

Christians regularly talk about God’s presence in space, but what do we mean when we use such language? I discuss this issue in the following passage on pages 22-23 of my 2009 book Finding God in the Shack:

“if you go to church on a Sunday morning you might hear the pastor address the hushed congregation with the words: ‘The Lord is in this place.’ But what does that mean? That God is only in this place? Isn’t he everywhere? Or one might hear the worship leader pray: ‘Lord, come into our presence!’ Come here … as if God wasn’t here already? Where is he coming from? If someone who had never heard of God before were to visit a church, he could easily think that God was a person [or three people] running around the world visiting different congregations: ‘Okay, the Holy Spirit will be at Poughkeepsie Pentecostal Church for the 9:00 A.M. service. Jesus, you go to the Albuquerque Alliance Church for the 9:30 and we’ll all meet up at St. Claire’s for the 10:00 A.M. mass.’” (Finding God in the Shack, Biblica)

Such a picture is absurd, of course. God doesn’t move about in space, he’s everywhere, a fact that the psalmist memorably conveys in Psalm 139:7-10:

7 Where can I go from your Spirit?

Where can I flee from your presence?

8 If I go up to the heavens, you are there;

if I make my bed in the depths, you are there.

9 If I rise on the wings of the dawn,

if I settle on the far side of the sea,

10 even there your hand will guide me,

your right hand will hold me fast.

The psalmist certainly does express the orthodox doctrine of divine omnipresence with eloquent poetry. But it still brings us back to the question: what does it mean to say God is in the heavens … and in the depths, and everywhere in between?

The psalmist certainly does express the orthodox doctrine of divine omnipresence with eloquent poetry. But it still brings us back to the question: what does it mean to say God is in the heavens … and in the depths, and everywhere in between?

In this episode of The Tentative Apologist Podcast we take on the question of divine omnipresence with theologian James Gordon. Dr. Gordon has his PhD from Wheaton College where he is currently a guest professor of philosophy. He is also the author of the recently published book The Holy One in Our Midst: An Essay on the Flesh of Christ. You can visit him online at www.jrgordon.me.

In this conversation Dr. Gordon brings his formidable skills in analytic philosophy to bear in understanding the complexity of that simple declaration: God is everywhere.

April 19, 2016

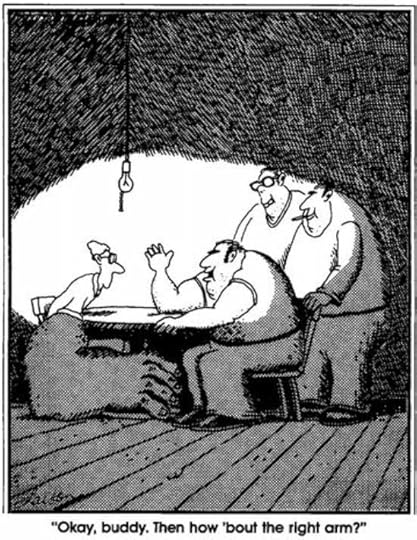

The Problem with Hell in One Cartoon

I’m a long time fan of Gary Larson’s comic strip The Far Side and this cartoon is one of my favorites. Not only does it capture the bizarre, off-beat humor for which The Far Side is justly famous, but it also succinctly summarizes a problem with the conception of God punishing people eternally in hell.

I’m a long time fan of Gary Larson’s comic strip The Far Side and this cartoon is one of my favorites. Not only does it capture the bizarre, off-beat humor for which The Far Side is justly famous, but it also succinctly summarizes a problem with the conception of God punishing people eternally in hell.

How so?

Well, let’s start with the cartoon. There are only two reasons that the fellow in the panel would ask for a right arm wrestling match. Either (1) he is unaware of his would-be opponent’s giant arm or (2) he is aware of that giant arm and nonetheless has a fundamentally irrational conception of his own abilities.

In either case, it would seem to be inappropriate for “Mr. Armstrong” to accept the invitation to arm wrestle.

Let’s start with the first scenario. The intuition here is that when person 1 is grossly outmatched in abilities relative to person 2, person 2 ought not accept a challenge from person 1 until person 1 appreciates the grossly disproportionate nature of the match-up. (Incidentally, there are conceivable instances where this intuition would not apply but they do not apply to the extrapolation to hell and so I will not discuss them here.) If this intuition is correct then Mr. Armstrong has an obligation to make his opponent aware of his giant arm before he consents to enter into the match.

As applied to hell, the reasoning would be that for the individual to be held accountable for the eternal penalty of hell, that individual must first be made aware of the gross mismatch between their own creaturely finitude and the infinite majesty and power of the God against whom they are rebelling. Barring that information, it would not be appropriate to damn that individual just as it would not be appropriate for Mr. Armstrong to agree to arm wrestle his challenger.

But what if the challenger is aware of Mr. Armstrong’s enormous appendage and still wants to arm wrestle him? Here one might reasonably conclude the following: if this man’s insistence that he can beat Mr. Armstrong is borne of a fundamental disconnection from reality — an inability to think rationally about the bleak prospects of winning any such match-up — then Mr. Armstrong would still be under an obligation not to consent to the match. This conclusion is based on the intuition that it is wrong to consent to the challenges issued by people who are behaving in a fundamentally irrational manner.

Imagine, for example, that an angry 95 pound weakling with a bad temper challenges the heavy weight boxing champion of the world to a fight. The champ could certainly knock that weakling into next Tuesday, but if he is a man of good nature and self-control who can assess the fundamental self-destructive irrationality of his challenger, then he would refrain from accepting the challenge.

If that Far Side panel depicts a gross mismatch, it pales in comparison with the infinite chasm between God and any finite creature. Consequently the intuition would suggest that where individuals seek to challenge God, God would recognize the fundamental irrationality of his challenger and would refrain from acting as surely as the principled world-class boxer.

April 17, 2016

Thoughts on Certainty: The Evangelical Leader and the Liberal Bishop (Part 2)

In my opening installment of this series I cited Dave Tomlinson’s parable of the evangelical leader and liberal bishop. I’m now going to begin offering some critical response to it.

I’ve already observed how the parable is intended to be provocative and paint our two leaders in stark tones. And because it is aimed at evangelicals, the liberal is the one presented sympathetically. Were Tomlinson to write a parable intended to be a pebble in the shoe of liberal Christians, presumably the story-line would be different.

Even so, there are points on which it is worth pushing back, and in this article I want to focus on one of them: the question of certainty. As Tomlinson draws the contrast, the evangelical is confident in his convictions. The liberal, by contrast, is awash in doubt: “Virgin birth, water into wine, physical resurrection. These things are hard to believe in, Lord. In fact, I’m not even sure I’m in touch with you in a personal way.” What is more, the doubting liberal is presented sympathetically while the evangelical, with all his confidence and certainty, is not.

I can agree with the spirit of the parable on one point: publicly proclaiming your personal certitude tends to quash further conversation. Imagine that you enter into a conversation with another person on some particular topic and immediately they state their own certainty in the rightness of their opinions. At that point you’d likely be a little less interested in continuing the conversation. And this for good reason: such avowals would tend to signal a closed mind uninterested in further dialogue and thoughtful reflection. Consequently, many people perceive a negative correlation between certainty and open-mindedness.

Given this fact, it is no surprise that many people in the conversation-focused post-evangelical, emergent camps are keen to criticize traditional evangelical declarations of certainty. The titles of two recent books capture the general sentiment: Greg Boyd’s Benefit of the Doubt: Breaking the Idol of Certainty and Peter Enns’ newly released The Sin of Certainty: Why God Desires Our Trust More Than Our “Correct” Beliefs. I haven’t read either book (though reviews suggest they are both worthwhile). And I do share these concerns that public declarations of certainty undermine dialogue and potentially flag a closed-mind.

But not all objections to certainty are of equal strength. Another concern is more problematic, and that is the tight association that many draw between certainty and intolerance. Consider the following passage from John J. Collins’ booklet Does the Bible Justify Violence?:

“historically people have appealed to the Bible precisely because of its presumed divine authority, which gives an aura of certitude to any position it can be shown to support—in the phrase of Hannah Arendt, ‘God-like certainty that stops all discussion.’ And here, I would suggest, is the most basic connection between the Bible and violence, more basic than any command or teaching it contains.” ((Augsburg Fortress, 2004), 32.)

Collins picks up on the concern that certainty “stops all discussion”. He also rightly raises a concern about a disproportionate confidence in the fallible human readings of scripture.

But he goes further than this by suggesting that certainty is correlated with violence and thus intolerance. As Collins says, “the most basic connection between the Bible and violence” is “God-like certainty”.

Here’s an example that Collins would surely resonate with. In his great play “The Persians” the Greek playwright Aeschylus memorably challenges the warring spirit as expressed in the voice of the conqueror:

“All those years we spent jubilant, seeing the trifling, cowering world from the height of our shining saddles, brawling our might across the earth as we forged an empire I never questioned. Surely we were doing the right thing…. It seemed so clear—our fate was to rule. That’s what I thought at the time. But perhaps we were merely deafened for years by the din of our own empire-building, the shouts of battle, the clanging of swords, the cries of victory.”

The fact that this warrior begins to question his own motives and the rightness of his cause is a good thing. And in that case, it is to everyone’s benefit that we insert some doubt into the warring spirit and the confident ideology that underlies it.

But a moment’s reflection suggests the real problem here isn’t certainty per se. Rather, it is that of which one is certain. I might rue the certainty of moral conviction that leads a Hutu to butcher his Tutsi neighbors. But I don’t rue the certainty of moral conviction of the UN peace keeper who risks his life to save the very Tutsis whose lives are under threat.

And if the evangelical is certain of the virgin birth, water into wine, and the physical resurrection, who am I to criticize her?

In short, the problem isn’t certainty per se. Rather, the problem is how you are certain (don’t express your certainty like the evangelical leader in the parable) and of what you are certain (don’t be certain of morally problematic or evil campaigns and projects like the Persian empire-building or the Hutu genocide of Tutsis.

But let us not attack the idea of certainty in itself, for to do so is confused and misbegotten. Of that much I am certain.

April 15, 2016

When did common sense become victim blaming? A vote for John Kasich

Today at a town hall John Kasich was asked by a first year female university student how the presidential hopeful could help her “feel safer and more secure regarding sexual violence, harassment and rape”. (See the CNN article “Kasich responds to question about sexual assault.”) After making some policy observations and observing that he worried about the safety of his two sixteen year old daughters, Kasich added:

“Well I would give you, I’d also give you one bit of advice. Don’t go to parties where there’s a lot of alcohol. OK? Don’t do that.”

The Democratic National Committee quickly responded that Kasich was “blaming victims of sexual and domestic violence.”

You could dismiss that ridiculous comment as mere political spin. But it is far worse than that.

Just think about it. As a first year university student this young lady is probably 18-19 years old. In other words, she is well under the legal drinking age in New York State (21). And regardless of whether she drinks or not, in all likelihood a university party will include illegal underage possession and consumption of alcohol.

So the DNC is indignant that John Kasich recommended that a young lady avoid situations in which it is highly likely that significant numbers of people will be engaged in illegal behavior.

While the question of legality is important, the most crucial part of Kasich’s advice is that situations where significant numbers of minors and young legal adults are consuming alcohol are high risk. Kasich’s advice is no different from advising a young person to buckle their seat belt and not accept rides from drivers who have a suspended license.

The problem isn’t Kasich. Rather, it’s the DNC which is apparently content to impugn people who advise young women to avoid high risk situations with illegal behavior.

Thoughts on the Evangelical Leader and the Liberal Bishop (Part 1)

What is the relationship between belief (or right doctrine) and character? In this provocative parable of “The Evangelical Leader and the Liberal Bishop”, Dave Tomlinson challenges the common evangelical mind-set to prioritize right doctrine over character:

“Jesus told a parable to a gathering of evangelical leaders. ‘An evangelical speaker and a liberal bishop each sat down to read the Bible. The evangelical speaker thanked God for the precious gift of the Holy Scriptures and pledged himself once again to proclaim them faithfully. “Thank you God,” he prayed, “that I am not like this poor bishop who doesn’t believe your Word and seems unable to make his mind up whether or not Christ rose from the dead.” The bishop looked puzzled as he flicked through the pages of the Bible and said, “Virgin birth, water into wine, physical resurrection. These things are hard to believe in, Lord. In fact, I’m not even sure I’m in touch with you in a personal way. But I’m going to keep on searching.” “I tell you” said Jesus, “that this other man, went home justified before God. For those who think they have arrived have barely started out, but those who continue searching are closer to the destination than they realize.’” (the post evangelical, rev. North American edn. (El Cajon, CA: emergentYS books; Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003), 69-70.)

This parable captures the spirit of Tomlinson’s book the post evangelical which was an important harbinger for the rise of emergent/emerging Christianity. And your reaction to it will likely depend on how sympathetic you are to evangelicals.

I can envision more than a few evangelicals protesting the portrayal as unfair at best and anti-evangelical propaganda at worst. And of course there is no denying that the contrast is set up with black and white categories that do not accurately reflect the nuanced grays of so much of life.

That said, it is worth considering how the original Jewish audience would have reacted upon hearing the parable of the “Good Samaritan”. One can imagine that many would have similarly protested the portrayal of Jewish leaders over-against the Samaritan as unfair at best and propaganda at worst. The point of such black and white categories is to irritate, destabilize, and ultimately to facilitate personal introspection.

And so, our question should be whether this parable illumines for the evangelical ways in which the evangelical in-group can miss the mark and ways in which the liberal out-group can hit the mark.

In the next few posts I’m going to be exploring some of the themes raised by Tomlinson’s parable.