Randal Rauser's Blog, page 125

May 5, 2017

Faith, Story, and The Shack Controversy

I was recently interviewed talking about The Shack (book and film) as well as the idea of Christian art. The article appears in the May/June edition of Faith Today (Canada’s answer to Christianity Today) and I’ve included it below:

For the latest magazine in which this article is featured click here.

The post Faith, Story, and The Shack Controversy appeared first on Randal Rauser.

May 4, 2017

Conservative evangelicals think Donald Trump is the next Constantine

Meeting of the minds

The fourth century did not begin well for Christians. In 303 a series of edicts from Emperor Diocletian initiated an empire-wide persecution of Christians, a persecution that only ended years later when Constantine became emperor (312 in the Western Empire; 324 in the East). From that point Constantine began to adopt the Christian church as his favored religion and the rest is history.

But what kind of history? To say the least, that history is a mixed bag. On the one hand, Constantine halted persecution of Christians, and that is undoubtedly a good thing. On the other hand, within a few decades the Christian church was actively persecuting the “pagans” in a lamentable illustration of Psalm 137. (Read the psalm. It’s amazing how quickly we move from the persecuted to the persecutor.) To make matters worse, the church which had once been lean and mean now began to suckle at the civic teet. Needless to say, it is difficult to maintain a prophetic stand against the very institution that’s paying your bills.

Fastforward to 2017. With all due respect, conservative evangelicals in the United States on the whole do not have a clue what real persecution is like. But you’d never know that by watching Fox News or reading conservative blogs. Whether it is the perpetual “war on Christmas,” the intolerable demand to bake cakes for gays, or pay for contraception for employees, evangelicals constantly feel under attack. Climate change? Meh. But evangelical persecution? Rally the troops!

So who would have thought the next Constantine would be an amoral, misogynistic, irreligious business man? Actually, if you read a biography of Constantine, you probably won’t be too surprised: that man was no angel. As for Donald Trump, yesterday Franklin Graham met with him to encourage and pray for him as he restores the fortunes of beleaguered evangelicals in American society. Today Graham described the encounter on Facebook:

Last night I was at the White House for dinner with other pastors and Christian leaders from across the country. I thank God that we have a president who seeks the counsel of men and women of God. He is set to sign an executive order today that helps protect churches and Christian organizations. (Source)

Franklin says he is glad to “have a president who seeks the counsel of men and women of God.” He meant to say he is glad to have a president who seeks the counsel of conservative Republicans like himself.

I have nothing against Republicans. Or conservative evangelicals. I just don’t think that “Republican” or “conservative evangelical” or “conservative Republican evangelical” is the same thing as “man or woman of God.” Godly people are found across the spectrum of political opinion. And marrying Christianity to a political party never ends well.

The post Conservative evangelicals think Donald Trump is the next Constantine appeared first on Randal Rauser.

May 1, 2017

Does Faith Make Sense? A Sermon on Christianity and Evidence

This is a sermon I preached yesterday at McKernan Baptist Church in Edmonton as part of their “Questions from the Neighborhood?” series. At the beginning I note that the most common objection I’ve encountered toward Christianity concerns the problem of evil. But the second most common objection is that Christianity demands faith at the expense of evidence, that it commends blind assent rather than careful reason. Hence the question, Does faith make sense?

In response, I point out that on the contrary, Christianity is based on evidence right back to the life and ministry of Jesus and his earlier followers. They were always concerned to ground faith — that is, trust — in the right kind of evidence. And so should we.

The post Does Faith Make Sense? A Sermon on Christianity and Evidence appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 30, 2017

A Little Learning is a Dangerous Thing, or the biggest problem with popular Christian apologetics

Thirty years ago popular Christian apologetics (henceforth PCA) was thin on the ground: Josh McDowell, John Warwick Montgomery, Norman Geisler, and a smattering of others largely carried the field. But these days the field of PCA is crowded with luminaries ranging from distinguished academics (e.g. William Lane Craig; Gary Habermas; Timothy McGrew) to lay church leaders (e.g. Ravi Zacharias; Lee Strobel).

The result has been an explosion of apologetics on the ground in the local church. And it is at this point that I find the current state of affairs decidedly more mixed. With an abundance of William Lane Craig debates, podcasts at Unbelievable and articles at Apologetics 315, the material available for the autodidactic (i.e. self-taught) apologist (henceforth AA) is endless.

And that’s the problem.

With no curation of sources, no external guidance in one’s self study, one ends up merely following through points of self-interest. And the result is a series of massive gaps in education.

For example, the AA might invest extensive time developing arguments to defend biblical inerrancy and intelligent design theory because that reflects his/her needs and interests. As a result, the individual ends up knowing a fair amount about how theologically conservative apologists have developed arguments to defend these claims. (Cynically put, they are adept at reproducing a long list of talking points to establish their case and offer counter rebuttals.)

However, despite the surface patina of intellectual seriousness, the actual case is seriously weak.

The defense of inerrancy is hampered critically by the fact that this person has never studied hermeneutics (i.e. the methods of interpretation). Nor does that individual have any acquaintance with various nuanced theological models of inspiration, models which are essential for providing a meaningful and defensible definition of inerrancy in the first place. Nor has the person studied epistemology, and the extent to which particular modernist epistemologies (e.g. strong foundationalism; evidentialism) have led Christians in the modern era to tying biblical inspiration and authority to some woolly conception of “inerrancy”.

The gaps are equally evident in that defense of intelligent design theory. Here too, the lack of any background in hermeneutics hampers one’s engagement with the biblical text. His/her lack of formal theological study leaves him/her wholly unaware of various models of divine action. Not surprisingly, the individual tends to be unable to appreciate the nuanced difficulties with the God-of-the-gaps problem. One’s lack of formal study in epistemology and philosophy of science leaves him/her unclear on how to engage various theories and models from falsificationism to methodological naturalism.

Sadly, I don’t see the situation changing any time soon. And the responsibility must be borne, at least in part, by the luminaries of this PCA themselves, at least to the extent that they have encouraged the notion that a substantive defense of Christianity can be undertaken whilst bypassing the formal study in fields like biblical studies, theology, and philosophy. To that end, I submit that we present PCA with a serious and sober caveat, one that was famously stated by Alexander Pope:

A little learning is a dangerous thing;

drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

there shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

and drinking largely sobers us again.

One more thing: all that I have said applies equally to popular atheistic apologetics. Folks, if you want to critique Christianity, please invest some time studying hermeneutics, biblical studies, and theological studies (not to mention philosophy). By all means, critique Christianity, but do so from the perspective of one who is familiar with the intellectually sophisticated forms of Christian belief. Too many atheists treat their atheistic apologetic enterprise simply as a tortured means of exorcising the fundamentalist demons of their Christian past.

The post A Little Learning is a Dangerous Thing, or the biggest problem with popular Christian apologetics appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 29, 2017

Who is Eric Schneider and why is he defaming Bruxy Cavey?

Yesterday I became aware of a nasty article by a fellow named “Eric Schneider” who has a blog devoted to destroying the reputation and ministry of Bruxy Cavey. The article was poorly argued and evinced little by way of analytic skills, biblical or theological knowledge, or a modicum of charity. So who is Eric Schneider? Does he have any professional affiliations or advanced degrees in theology? He doesn’t say. All he says on his blog description is that he is an “avid fisherman” and has an interest in “theology, apologetics, and history.”

Over the years I’ve seen many leaders and academics in the Christian community attacked and defamed by self-appointed heresy hunters like Eric. And like Eric, they generally lack any accountability for their actions. Sadly, the internet provides a marvelous place to slander Christian leaders from the comfort of one’s private study.

I wrote a response to Eric and posted a link at his blog. One day later, he has still refused to approve my comment so his readers can be made aware of a critical rejoinder to his screed. So I posted a second comment — also as yet awaiting moderation — on his blog:

Eric did comment in response to my blog, however. It was an illuminating, if abortive, exchange. Here I’d like to focus on one essential point. Eric cites the first few minutes of the following excerpt from Bruxy Cavey teaching to illustrate that Bruxy allegedly rejects scriptural authority:

However, in the comment section (in response to another commenter) I pointed out that Eric appears to have fundamentally misunderstood Bruxy’s point. I then laid out a charitable interpretation of Bruxy’s comments as follows:

“I watched the entire clip from the beginning to 3:50 (at which point it advances to later in the lecture). And having watched that whole section it seems clear that Eric has simply misunderstood what Bruxy is saying.

“In this section, Bruxy begins by contrasting two views of scriptural authority. The conservative evangelical roots that authority in the status of the Bible as an inerrant word from God. In the second, scriptural authority is sourced in God and his Word, Jesus Christ. Bruxy is not, in fact, disputing the Bible’s authority. Rather, he is attempting to source that authority in the Bible’s status as a word from God rather than a word that is without error.

“To make his point, Bruxy illustrates the problems with the inerrantist approach to authority by citing Bart Ehrman’s well-known story from “Misquoting Jesus” that his faith was shaken when he discovered a single error in the Gospel of Mark. Thus, Bruxy suggests, rooting biblical authority in inerrancy leads to an unstable faith which is liable to defeat with a single error.

“What he’s saying here sounds very much like Barth’s and Brunner’s Neo-orthodoxy.

“At the end of the section, He turns to Paul’s confession of all Scripture as being God-breathed and he notes that the point Paul draws from this is not that Scripture conveys inerrant facts but rather that it is useful for bringing about transformation in the individual who submits to it.

“Whether one agrees with Bruxy or not, it seems to me very misguided to think he is denying biblical authority simpliciter in a way that would put him at odds with the TSB. Rather, he is aiming to ground a proper biblical authority in the Bible’s divine source and its power to transform individuals into the image of God in Christ.”

I then asked Bruxy whether my synopsis was correct. Bruxy replied that it was, indeed, correct. This is what he wrote to me:

“[Yo]u are right on. Relative to other written sources, I say the Bible is authoritative. We have no other God-breathed sources like the Bible. We let the Bible have that place of authority in a way we do not grant any other book or prophet. But to a room full of people who already believe the Bible, I say that isn’t enough. Because the Bible records Jesus saying he is our great ultimate authority. And it seems to me (and I think other Anabaptists), that Reformed Christians back in the day (and maybe some today), have needed to have us find as many linguistic ways as possible to remind them to submit to Jesus’ authority rather than to the Bible in general, lest they keep using violence to fight for theological purity.”

So my interpretation of Bruxy was not only charitable, it was also correct. And thus there is demonstrably no conflict between this passage and the Tyndale Statement of Faith.

How do you think Eric responded to this irrefutable evidence that he had made a false claim against a brother in Christ? Did he say he would retract the charge based on the evidence provided? No, he did not. Instead, he posted this extraordinary comment:

“I take your accusation that I am uncharitably smearing a brother seriously and will think and pray on it, but at this point I really do not think that I am. If it is the case that I am guilty of this then I pray that God would show me that. Until that happens I do not intend to back down.”

I replied:

“Praying is great, but that doesn’t excuse you from addressing the arguments I’ve presented.”

To suggest that one can avoid the evidence demonstrating they have professed falsely about another person by sanctimoniously appealing to “prayer” is the very definition of pharisaical behavior.

My penultimate word to Eric Schneider would be a matter of legal caution:

Mr. Schneider, you are disparaging the reputation of both Bruxy Cavey and Tyndale Seminary by suggesting Mr. Cavey is acting in bad faith by signing Tyndale’s Statement of Faith and that Tyndale is acting in bad faith by allowing him to teach. I’m no lawyer, but you could be opening yourself to a defamation lawsuit. One thing is clear: you have shown yourself to be a person lacking in some of the fundamentals of Christian character.

And my final word goes to the rest of us. Eric is engaged in bullying behavior. And as Barbara Coloroso has pointed out, bullying proceeds with a dynamic of three: the bully, the one bullied, and the bystander. The critical point to recognize is that by doing nothing, the bystander empowers the bully. If we are silent when self-appointed heresy hunters like Eric Schneider engage in character assassination, we are de facto empowering their bullying. There is no neutral stance here. When you see this kind of behavior, speak out and call the bully to account.

The post Who is Eric Schneider and why is he defaming Bruxy Cavey? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 28, 2017

Charity and Confession: The case of Bruxy Cavey and Tyndale Seminary

Today I came across a blog article titled “Why is Bruxy Cavey Teaching at Tyndale?” (Bruxy is a leading figure in progressive Christianity, an author (here’s his latest book) and pastor of one of the largest churches in Canada. Tyndale Seminary is a large evangelical seminary in Toronto.)

The blogger who wrote the article, a fellow named Eric, is concerned that Bruxy deviates from Tyndale’s Statement of Belief (henceforth TSB) on two points: the doctrine of Scripture (in particular, the authority and inerrancy of Scripture) and the vicarious understanding of the atonement. To make his case, Eric provides several quotations in which Bruxy makes statements where he speaks critically of scriptural authority/inerrancy or (penal) substitutionary atonement. Eric assumes that these statements are inconsistent with the confessions of the TSB. And thus, he concludes that Bruxy should not be teaching at Tyndale.

What is at stake?

It’s important to begin with a recognition that raising objections to the orthodoxy or integrity of an individual or institution is serious business. To frame just how serious it is, I want to turn for a moment to the 2008 film Doubt. This critically acclaimed film tells the story of Sister Beauvier (played by Meryl Streep) who begins to raise concerns that the local parish priest, Father Flynn (played by Philip Seymour Hoffman), is engaged in a sexual relationship with a young boy in the parish. Sister Beauvier has some middling circumstantial evidence to support her claim, but the evidence is far from determinative.

Not surprisingly, Father Flynn repudiates the charges categorically and is deeply offended at this half-baked assault on his character. He drives the point home in a riveting sermon illustration:

In terms of high drama, this rivals Nathan pointing at David and declaring “You are the man!” (2 Samuel 12:7) It also has relevance for the current case. To be sure, I’m not claiming that the gravity of Eric’s charge against Bruxy and Tyndale parallels Sister Beauvier’s charge against Father Flynn (or Nathan’s charge against David).

Rather, I am simply pointing out that in each case, a serious charge is being raised which could adversely affect the life, livelihood, and reputation of an individual and institution. Given the extremely serious ramifications of rendering a false charge in this circumstance, one had better be sure they have done the requisite work before making that charge.

A Starting Point of Charity

Before we call an inquest, it is important that we begin with the right orientation to investigation, and that is the principle of charity. According to this principle, you seek a favorable (or charitable) interpretation of the beliefs/actions of another person unless you have an overriding reason to do otherwise. Colloquially speaking, it’s called giving people the benefit of the doubt. While there are many reasons to accept the principle of charity, one excellent reason is because it is derivative of the Golden Rule. I presume, for example, that Eric would prefer other people to interpret his statements charitably if possible. So by the Golden Rule, he should likewise extend that charity to others.

How would charity be applied in a case like this? To begin with, in his article Eric cites President of Tyndale, Gary Nelson, who wrote that “All faculty, both full time and part time, must sign the TSB before they can teach at Tyndale.” Thus, it follows that Bruxy has likewise signed this statement.

This is where charity comes in. One begins by assuming the following: Bruxy has signed the TSB in good conscience and Tyndale has accepted his assent to the document.

Statements of Belief are interpreted

But how can this be?

Simple: statements of belief are never simply read; rather, they are interpreted. While this may be a truism, it is one that needs to be rendered explicit in this case. Interpretation occurs within a preexistent semantic range, i.e. a range of acceptable meanings. So we can assume that Bruxy’s interpretation of the TSB is considered to be within the semantic range of interpretations considered to be acceptable by Gary Nelson and Tyndale.

Thus charity brings us back to all the citations that Eric provides. It must be the case that Bruxy is not repudiating biblical authority or inerrancy simpliciter. Rather, he is rejecting one or more interpretations of these doctrines. While those particular interpretations may be consistent with the TSB, they are clearly not required by the TSB. And thus, there is no inconsistency or lapse of integrity in Bruxy signing the document and teaching at Tyndale.

Charity or Tunnel Vision?

Unfortunately, Eric never invests time exploring the semantic range of interpretation for doctrines like biblical authority or inerrancy. On the contrary, so concerned is he to prosecute his case that he tendentiously limits the semantic field to serve his polemical ends. (To be sure, I am not suggesting he does this intentionally. Rather, I suspect it is the unintended byproduct of motivated reasoning and confirmation bias.)

Consider, for example, how Eric attempts to tie the TSB to the penal substitutionary theory of atonement (Bruxy explicitly rejects the penal substitutionary theory):

“When we speak of vicarious atonement we are speaking of the fact that Christ took our place in the atonement in some way. The Tyndale Statement of Faith specifically says that they are rooted in the Protestant Reformation. The Reformed view of vicarious atonement is Penal Substitutionary Atonement.”

This excerpt is apparently attempting to present an argument. This is my attempt to reconstruct that argument:

(1) The TSB affirms doctrines rooted in the Protestant Reformation.

(2) The doctrine of penal substitutionary atonement is rooted in the Protestant Reformation.

(3) Therefore, the TSB affirms the doctrine of penal substitutionary atonement.

Unfortunately, this argument is utterly fallacious for at least three reasons. First, (3) does not follow from (1) and (2). The reason is because (1) only states that the TSB affirms doctrines rooted in the Protestant Reformation, not that it affirms every particular doctrine rooted in the Reformation.

Second, (2) implies that the Protestant Reformation has a single view of atonement: penal substitution. But this is false. Other theories of atonement are also “rooted” in the Reformation: for example, Martin Luther is widely considered to be a defender of a Christus Victor view. In addition, Anabaptist perspectives on atonement also differ in important ways from the magisterial perspectives.

Third, the verb “rooted” is inherently ambiguous. Eric seems to assume it entails that current faculty at Tyndale are obliged to accept the same version of doctrines affirmed by key Protestant Reformers. (And which Reformers exactly? Calvin? Luther? Bucer? Melanchthon? Oecolampadius? Simons? Zwingli?) But “rooted” could also be interpreted as meaning that current beliefs trace their organic development to the Reformation. And that latter interpretation allows for all sorts of differences between the Reformation original and the current form. (Just consider how different an acorn is from an oak tree.)

Oh yeah, and by Eric’s standard, N.T. Wright shouldn’t be allowed to teach at Tyndale.

Suffice it to say, there is little by way of charitable interpretation or nuance in Eric’s article. There is no attempt to explore the semantic range of interpretation for the various confessions contained within the TSB. Nor is there an effort to understand the senses in which Bruxy affirms biblical authority, inerrancy, or atonement. Instead, there is a one-sided case leveling serious charges which is followed by a rallying cry to action.

The sad irony is that an institution of higher learning like Tyndale exists at least in part to form students to acquire the measured nuance and background knowledge for the kind of careful and charitable interpretation that is absent from this article.

The post Charity and Confession: The case of Bruxy Cavey and Tyndale Seminary appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 26, 2017

Universalism, Evangelicalism, and The Shack

The book cover that should not have been.

Two days ago I came across this article at CBN: “Art Designer of ‘The Shack’ Book Cover Says He Regrets His Involvement.” In a Facebook post of three weeks ago, Dave Aldrich states that he lacked discernment when he agreed to illustrate the book cover for The Shack a decade ago. He now recognizes that the theology is “unbiblical”, that it distorts the Bible, and most of all that it teaches universal salvation.

Before we get to The Shack, I want to say a word about Young’s provocative new book titled Lies We Believe About God. In this book, Young does appear to endorse universal salvation:

“The Good News is not that Jesus has opened up the possibility of salvation and you have been invited to receive Jesus into your life. The Gospel is that Jesus has already included you into His life, into His relationship with God the Father, and into His anointing in the Holy Spirit. The Good News is that Jesus did this without your vote, and whether you believe it or not won’t make it any less or more true.

“What or who saves me? Either God did in Jesus, or I save myself. If, in any way, I participate in the completed act of salvation accomplished in Jesus, then my part is what actually saves me. Saving faith is not our faith, but the faith of Jesus.

“God does not wait for my choice and then ‘save me.’ God has acted decisively and universally for all humankind. Now our daily choice is to either grow and participate in that reality or continue to live in the blindness of our own independence.

“Are you suggesting that everyone is saved? That you believe in universal salvation?

“That is exactly what I’m saying!” (Lies We Believe About God, New York: Atria, 2017, 117-118)

At this point Young goes on to argue that Christ has already secured the salvation of all and he refers the reader to a list of texts in support of his claim. I haven’t studied Young’s current views with any great care, but his statement of his views here appears to share much with Karl Barth’s understanding of Christology and election, though Barth backs off from endorsing universalism.

So for the purposes of our conversation, we can assume that Paul Young currently appears to endorse universal reconciliation in Christ. Please note that this does not entail a denial of hell. Young might well believe, for example, that people can continue to deny the life they have in Christ for an indefinite period of time both in this life and the next. And that self-imposed misery that results would be a self-imposed hell. (Young may address these issues elsewhere in his book. I’ve only read the relevant section for this article.)

Having said all that, I have several problems with Aldrich’s Facebook comments. First, The Shack does not teach universalism. It certainly has a hope of universal reconciliation, but then what kind of Christian wouldn’t hope for the reconciliation of all? (Answer: a bad Christian.)

Second, while Aldrich is correct to note that stories can teach theology, if you disagree with the theology of a book, the proper response is not to pull out the ole’ heresy stamp. Rather, it is to equip others with the skills of discernment. After all, even if The Shack has some error in it — and which book produced by mere humans doesn’t? — you engage it by discerning the truth from the error.

(I continue to remain bemused by the extent to which evangelicals tout C.S. Lewis, apparently oblivious to the theological positions he endorsed. Had Lewis lived today, no doubt John Piper would have tweeted “Farewell Clive Staples” a while ago.)

Third, Aldrich’s condemnation of universalism — which consists of citing a couple Bible verses as if doing that somehow settles the question — is wholly inadequate. Of course, one can do that, if one likes. And one can also endorse complementarian gender relations with a couple citations from Paul. Or one can endorse adoptionism with a couple citations from the Gospels. Or one can endorse slavery with a couple citations from the Torah. But that’s not a sound way to engage in theological reflection.

Aldrich’s indictment of The Shack is intended to reflect a new level of discernment that he apparently lacked when he created the cover for The Shack. But it seems to me that the evidence is quite the opposite: if anything, it is his current ill-formed response to the book which evinces a distinct lack of discernment.

The post Universalism, Evangelicalism, and The Shack appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 25, 2017

An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a (Coffee) Bar: The Brew Podcast

When Justin Schieber was in Edmonton for our brief Alberta book tour, we recorded a podcast interview with The Brew Podcast. You can listen to the podcast and join the conversation by clicking on the cool image.

The post An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a (Coffee) Bar: The Brew Podcast appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 24, 2017

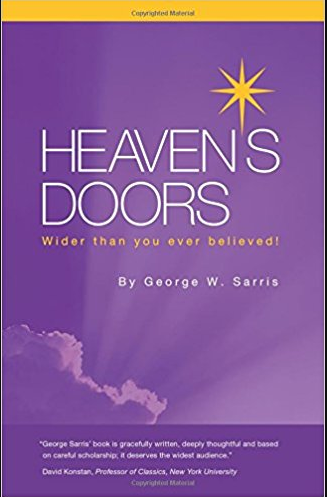

Universalism for Evangelicals? A Review of Heaven’s Doors

George W. Sarris. Heaven’s Doors: Wider than you ever believed! (Trumbull, CT: GWS Publishing, 2017).

George W. Sarris. Heaven’s Doors: Wider than you ever believed! (Trumbull, CT: GWS Publishing, 2017).

Though he has long been a great defender of the traditional doctrine of hell, J.I. Packer once conceded: “If you want to see folk damned, there is something wrong with you!” That statement has always stuck with me because it implies every Christian should hope universalism is true even if they believe it is false.

The Messenger

But should they believe it is false? George Sarris seeks to challenge that belief in his new book Heaven’s Doors: Wider than you ever believed! At first blush, Sarris is a surprising defender for universalism. He is neither an old school liberal nor an emergent/emerging hipster. Nor, for that matter, is he the kind of Eastern Orthodox theologian who defies the simplistic liberal/conservative continuum so beloved in the West.

Rather, Sarris is a traditional conservative evangelical and his credentials in this regard are impeccable. Don’t believe me? Well consider this: he is the voice narrating Zondervan’s audio edition of the NIV. You don’t get more evangelical than that!

Universalism in the Early Church

Like any good evangelical, Sarris takes the Bible seriously. But when it comes to the nature of hell, he believes a majority of Christians have misread its teaching for a very long time: approximately fifteen hundred years, to be exact (204). That’s quite the claim, and Sarris devotes several early chapters to arguing that universalism was the dominant position in the early church. To make his case he appeals to several theologians including Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, Theodore of Mopsuestia, and others. He also notes the notable silence of major creeds and ecumenical councils on the topic of hell.

All that began to change under the long shadow of Augustine who, Sarris argues, was the first great defender of eternal conscious torment. A century later, Emperor Justinian took up the cause, targeting universalism while helping to establish the hegemonic dominance of eternal conscious torment on subsequent debate. That hegemony has been maintained down to our own age.

I have some quibbles with aspects of Sarris’ historical theological work. For example, he fails to acknowledge the extent to which Platonism impacted Origen’s entire theological project. This seems a notable oversight since Sarris appears to marginalize the relative popularity of eternal conscious torment during the intertestamental period because it is sourced in “pagan writers” (31). But then might one dismiss Origen to the extent where his views were shaped by an architectonic Platonic framework? (For my money, I’d want to challenge the the whole underlying assumption: nonbiblical origin does not mean unbiblical, let alone unChristian content.)

Regardless, we must not miss the wood for the trees. At the very least Sarris provides a strong case that with the exception of Tertullian, Augustine, and the northern African church, universalism was widely considered to be a fully orthodox position in the early church. And that in itself is a very significant point.

The Heresy Question

This matters greatly because evangelicals frequently dismiss universalism by stamping it with the oft used (but rarely understood) stigma of heresy! The practical implications of this assumption are hammered home in the book as Sarris recounts how he lost friends, was fired from a ministry, and was even asked to leave his church all because of his commitment to Christian universalism.

What’s most disturbing about this is not the charge of heresy itself so much as the fact that it is regularly given in lieu of any conversation or analysis. The assumption seems to be that once you’ve labelled something “heresy”, you don’t need to worry about the arguments for it. As a case in point, Sarris recounts an instance where a friend asked his pastor to read Sarris’ manuscript. Initially the pastor agreed, “but after receiving a copy, [he] made a casual remark about it being heretical and said he wasn’t interested.” (82)

Time and again Sarris encounters the same response (e.g. 74, 104). How different that closed-minded attitude is from the Bereans who, when confronted with the extraordinary messianic claims of an itinerant evangelist, “examined the Scriptures every day to see if what Paul said was true.” (Acts 17:11) Sadly, I suspect Paul would never get a hearing in many evangelical churches today.

The Biblical Case

The question of whether we should consider a doctrine consistent with orthodoxy is important. But it’s even more important to ask whether we should consider it true. And for an evangelical the resolution of that question rests ultimately with Scripture.

Yet, doesn’t Scripture clearly teach that some people will be lost forever and endure an eternal punishment? Not according to Sarris, and he devotes three chapters (8-10) to a careful consideration of these issues. The problem, as Sarris rightly notes, is that too often the reader is left with questionable English translations and a background eternal conscious torment interpretive framework. But once we get beyond those barriers, Sarris believes we will find the texts saying something very different.

Sarris begins in chapter 8 by discussing the Hebrew term Sheol and the related Greek term Hades. While these terms sometimes are taken to be referring to hell (most notably in the Parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man in Luke 16:19-31), they in fact refer to the realm of the dead where people go immediately following death and prior to the general resurrection and final judgment.

Next, Sarris devotes chapter 9 to discussing references to Gehenna and Tartarus. Here he focuses in particular on Gehenna, arguing that a close analysis of the term in its literary and historical context simply does not support the doctrine of eternal conscious torment. But it is consistent with the image of fire as a purgative/cleansing agent.

Chapter 10 is devoted to two terms commonly translated as “eternal” or “forever” (olam, Hebrew; aion, Greek). Sarris argues that the terms are likely referring to a future period of indefinite (but most certainly finite) length. As for the related term “punishment” (kolasis, Greek), Sarris argues that the term should be understood as a punishment for rehabilitation/restoration rather than merely retribution. The conclusion is that verses like Matthew 25:41, 46 should be taken as envisioning a future indefinitely long period of restorative punishment rather than a never-ending punishment of retribution.

The final three chapters explore the nature of judgment and some remaining biblical and practical issues. There are several fascinating sections in these chapters. For example, Sarris addresses Jesus’ declaration that it would be better if Judas had not been born (Matthew 26:24; Mark 4:21). In fact, Sarris argues that we’ve misread the text because we’ve misread the pronouns. The actual meaning is not that it would be good for Judas if he hadn’t been born, but rather that it would have been good for the Son of Man:

“In that context, Jesus was not saying that it would have been better for Judas if he had never been born. Rather, Jesus spoke of His grief concerning the disciple who was about to betray Him, and in the process expressed His desire that it would be good for Jesus if Judas had not been born.” (187)

That was an interesting take on a text that I hadn’t encountered before.

Conclusions

Heaven’s Doors has many strengths. It is clearly and accessibly written with a minimum of technical verbiage (i.e. unnecessary big words!). And Sarris is a good communicator. I particularly appreciated his helpful explanation of the contextual function of the Greek word aion replete with clear analogies. Two hundred pages provides much food for thought, and the book is written with a general readership in mind.

I did have a couple disappointments. To begin with, while Sarris discusses dozens of Scriptural passages throughout the book, most of the textual references are consigned to the endnotes. As a result, there are several cases where one must flip to the end of the book to discover which biblical text Sarris is discussing. It would have been far more sensible and user-friendly to include all scriptural references with in-text parenthetical references.

Second, Sarris devotes surprisingly little attention to several texts that have long been claimed by universalists including Acts 3:21, Romans 5:12, Philippians 2:11, Colossians 1:20, and Ephesians 1:10. I found it ironic that so much time should be spent (albeit well spent) on critiquing traditional eternal conscious torment texts, but comparatively little should be devoted to strengthening the case with these prima facie universalist texts.

Though I have oft defended the hope of universalism, I’m not a universalist by conviction. But I have no doubt that Sarris is a deeply committed evangelical Christian and in Heaven’s Doors he has presented a well researched and eminently readable case that is well worth considering. So if you’re interested in this topic — and if you’re a Christian then you should be — then I suggest you be a good Berean: pick up a copy of Heaven’s Doors, and examine the Scriptures for yourself to see if what George Sarris says is true.

If you benefited from my review you can upvote it at Amazon.com.

The post Universalism for Evangelicals? A Review of Heaven’s Doors appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 23, 2017

Teaching the Controversy on Earth Day?

Yesterday CNN kicked dirt in the face of Mother Earth by featuring William Happer on a panel discussion. Happer is a climate change skeptic who — no surprise — “advises” Donald Trump on the environment. In this section he begins by pointing out that CO2 is a gas that occurs naturally in the environment (human beings breathe out 2 pounds of it a day, he says). From that he concludes that we ought not think of it as a pollutant.

Yesterday CNN kicked dirt in the face of Mother Earth by featuring William Happer on a panel discussion. Happer is a climate change skeptic who — no surprise — “advises” Donald Trump on the environment. In this section he begins by pointing out that CO2 is a gas that occurs naturally in the environment (human beings breathe out 2 pounds of it a day, he says). From that he concludes that we ought not think of it as a pollutant.

This, of course, is nothing more than truly malevolent obfuscation.

Let’s begin with a definition of “pollutant”:

“any substance, as certain chemicals or waste products, that renders the air, soil, water, or other natural resource harmful or unsuitable for a specific purpose.” (Source)

An excess of CO2 (and other greenhouse gases) in the atmosphere renders planet earth — or vast regions thereof — unsuitable (or less suitable) for the specific purpose of sustaining living populations of human persons. Therefore, CO2 is a pollutant relative to the human population. (Perhaps it isn’t a pollutant relative to the interests of algae or jellyfish, but that’s not relevant, is it?)

But whether you call it a “pollutant” or not is really just a matter of semantics. Imagine that your house is filling with water from a flash flood. By following Happer’s logic, you shouldn’t worry that the water line is rising up your steps because the liquid is “natural”: indeed it covers the surface of much of the earth. So you shouldn’t worry that it is about to cover your house as well.

What an appalling display. Fortunately, Bill Nye redeems the situation by calling out this lamentable exercise in “teaching the controversy”. Since approximately 97% of scientists accept human-induced climate change, Nye starts by pointing out the panel should include 97 experts representing the consensus for every three deniers. (To put it another way, the composition of this CNN “expert panel” grants climate change skepticism approximately ten times greater representation than exists within the field of science.)

Check out the exchange here and watch Nye shine a light into the fog of Trumpian-era truthiness.

The post Teaching the Controversy on Earth Day? appeared first on Randal Rauser.