Lijia Zhang's Blog, page 3

October 5, 2025

A new trend

In recent years, a new craze has swept through China’s tourist spots: dressing up in traditional costumes and posing dramatically against famous landmarks. The other day, my daughters decided to join the fun at the Confucius Temple 夫子庙, and what a performance it turned out to be.

The operation began at 4:30 p.m. in a photo studio. Because my sister knew the owner, the girls received VIP treatment with the best photographer, the best makeup artist, and, I suspect, the heaviest headgear in Jiangsu province. Each makeover took over an hour. By the time the photographer whisked them off to a bridge overlooking the Qinhuai River, the sun was setting, the red lanterns were glowing, and the teahouses were shimmering invitingly in the water.

At 7 p.m., they still hadn’t finished and had to join us for dinner in full regalia. They looked magnificent — if a little ghostly — their faces buried under a geological layer of white powder. Between the elaborate hairpieces and the heavy silk robes, they could barely relax or enjoy the food: the headgears were so heavy. After dinner, they, still wearing their trainers, hidden under the long dresses, marched off to continue the shoot, while I sensibly stayed behind, enjoying my tea and freedom from hairpins and headdresses.

Qianmen

Qianmen

Last night, I arrived in Beijing from Nanjing and stayed at a courtyard hotel near Qianmen, an area I’ve never known intimately. As I emerged from the subway station, the two magnificent towers—the Gate Tower and the Arrow Tower—rose before me, bathed in golden light. For a moment I stood still, taking in their quiet grandeur. What a fabulous city Beijing is, I thought, where I spent nearly two decades of my life, full of stories and seasons.

Qianmen, meaning “Front Gate,” has stood for centuries as the southern threshold of the Inner City, one of the capital’s most enduring landmarks. First built in the early 15th century as part of the capital’s vast city wall system, the towers once guarded the heart of the empire, serving both ceremonial and military purposes.

I used to go to Capital M, a refined restaurant nearby, partly for the incredible food and partly for its view of the towers. Another small pilgrimage into memory.

After dinner with a friend, I had a romantic impulse to stroll across Tiananmen Square, as I often did on quiet nights long ago. But the square was sealed off; visitors must now register at least a week in advance. Oh dear. The city has changed, the rules have multiplied. It made me feel even more nostalgia.

Haidilao

A Hot Pot Restaurant with Chinese Characteristics

It could only happen in China.

Haidilao—literally “scooping from the bottom of the sea”—is a wildly successful hot pot chain that has turned dinner into a full-blown variety show. The food is excellent, but that’s only half the story.

While waiting for a table, you’re offered free drinks, hot soy milk, cold plum juice, even watermelon seeds to nibble on. There’s a little reading corner if you feel studious, and a counter where you can buy lottery tickets if you’re feeling lucky. By the time you sit down, you’ve already lived a full day’s worth of emotional experiences.

If you’re dining in a private room, the entertainment begins. A performer appears, swirling across the floor, and—poof!—changes masks in a split second. Bianlian, or “face changing,” is an ancient Sichuan art form in which emotions transform faster than Beijing’s weather. Just as you recover from that spectacle, the “noodle guy” bursts in. He doesn’t just pull noodles. He dances with them, twirls them over your head, flings them in the air, and even brings his own sound system. You half expect him to take song requests. (Please, watch the video. You’ll laugh your teeth off!)

Every diner is entitled to a head massage or a manicure. I opted for the latter. As I was being pampered, I chatted with the weary-looking manicurist. She told me she’d started work at 8 a.m. and wouldn’t finish until 4:30 the next morning. “Working through the night?” I asked. “Yes,” she said, smiling faintly. This branch, near Nanjing South Railway Station, doubles as a refuge for stranded travelers: people who’ve missed their trains or can’t afford a hotel. I’ll bear that in mind.

Once again, it struck me: the success of Haidilao, like so many Chinese miracles, rests on the shoulders of migrant workers. My sister assured me the staff are well paid. I certainly hope she’s right.

October 3, 2025

Red flags over China

Red Flags Over China

In recent years, China has stepped up its patriotic education campaign, which includes the mandatory display of national flags during public holidays. The result? At this time of year, red flags are everywhere. They flutter from office buildings, sprout from residential compounds, line the highways, and dangle from e-bikes. Step into a fancy Western restaurant in Nanjing and you’ll find not one, but two miniature flags planted right in the middle of your candlelit table, as if they’re part of the cutlery. Nothing says romance like a steak, a glass of Bordeaux, and the Motherland staring at you from between the salt and pepper shakers.

It reminded me of an old image: Wu Qinhua, the heroine of the revolutionary ballet The Red Detachment of Women, standing tall, clutching the national flag with tears streaming down her face.

But perhaps there’s a kind of continuity here. Then and now, the flag is everywhere: on the battlefield, on the stage, and, these days, on your dinner table next to the crème brûlée.

My rocket factory

My Former Rocket Factory

My former military factory once played a part in China’s modernization drive. It was founded in 1865 by Li Hongzhang, a prominent statesman, as part of the Self-Strengthening Movement. Today, it has been transformed into the 1865 Creative Park. While some key sectors remain, other parts, including my former work unit that produced gauges and measurement tools, have been turned into media companies, design studios, creative industries, and, of course, restaurants.

This morning, after a delicious dim sum, my daughter, my niece Catherine with her husband and son, and I strolled around the grounds of my old factory. To my amazement, I found the very building where I once spent ten years greasing machine parts. In one photo, the gun stands just around the corner; in another, my daughter poses at what was once the entrance to my work unit.

The factory I knew was a place of noise, sweat, and drudgery. Now it hums with music, art works and ideas. Walking through the old gates, I felt time folding in on itself: the young woman I once was, oil-stained and weary, seemed to glance at me across the decades. The creative park is a lively, enchanting place — almost unrecognizable, yet rooted in the same bricks and beams.

I am glad the old factory has been given a second life. And I am glad, too, that I have found mine.

The Rape of Nanjing

Nanjing Massacre Museum

As a Nanjing native, I have visited the museum many times. Today, I made a point of taking my daughters there, hoping to deepen their understanding of a defining event in the history of our city. Being a national holiday, the crowds were immense, some visitors carrying white chrysanthemums as a tribute. Our guide mentioned that yesterday alone, some 25,000 people came.

The museum, established in 1985 on the site of a mass grave, is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Nanjing Massacre (December 1937 – early 1938), during which an estimated 300,000 civilians and unarmed soldiers lost their lives.

Since my last visit years ago, the museum has been renovated. Once again, I was struck by its design and the power of its presentation. It is vital to remember and preserve history—lessons that should resonate in every aspect of our lives in China today.

October 1, 2025

Bingling Grottoes

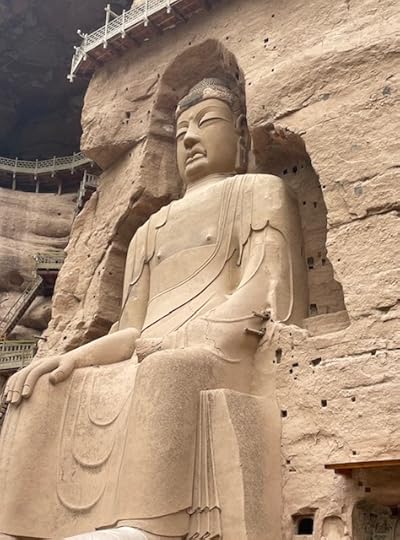

The Bingling Temple Grottoes (炳灵寺石窟)

I first visited Bingling some thirty-five years ago. Back then it felt adventurous: we skimmed across the Yellow River by boat, then wandered among the Buddhist grottoes carved into the cliffs, marveling at their scale and serenity.

This time, I sold the idea to my daughters: we’d ride a speedboat to this extraordinary complex, dating back to the 3rd century AD. They were just as excited as I was. But shortly before we reached Liujiaxia Reservoir by bus—the jumping-off point for the boats—the driver announced that it was “too late in the season” for speedboats. A taxi, he said, was our only option. Not to worry: he knew just the man. And sure enough, when we arrived, a driver was already waiting.

At the grottoes, however, I spotted several speedboats still in service. My suspicio deepened further when our driver, with a few phone calls, somehow persuaded the last bus to Lanzhou to delay its departure for us. Ah, the quiet miracles of China’s guanxi system!

As for the grottoes themselves, they are more polished now, less raw, perhaps a little of the old magic has been lost. Yet the site remains well worth the journey. Among the earliest grotto complexes in China, Bingling offers a vivid glimpse into early Buddhist art in the northwest. Over 180 caves and niches survive, sheltering hundreds of stone and clay statues, along with murals that together cover some 1,000 square meters. I still missed the speedboat ride, but in the end, that wasn’t really the point.

A Tibetan cave

As if to atone for our disappointment in Octagon Town, our next stop, White Rock Cave, turned out to be far more interesting than we had dared hope. A monk in crimson robes popped up at the narrow entrance like a ticket inspector at a fairground, collecting a modest fee before waving us toward the karst cavern beyond. Inside, the passages twisted and turned, slick with mud, probably the work of secret underground streams. The walls sprouted bizarre natural formations, said to resemble Tibetan letters or auspicious signs, though with a bit of imagination they could have been anything from dumplings to dragons.

Some stretches were so low and narrow we had to crawl on all fours, squealing and slipping like children let loose in a tunnel. It was ridiculous, but great fun. Considering I had spent the previous night bent over from altitude sickness, I thought I did admirably well, though perhaps the cave’s lower altitude had something to do with it.

At the far end gaped a pit, solemnly introduced as a ten-thousand-year-old sky burial site. To add weight to the setting, the cave also boasts archaeological significance: a human jawbone unearthed here is thought to be about 160,000 years old, one of the oldest in the region.

But the moment that truly fixed itself in my mind came when a Tibetan woman by the pit began to sing. Her voice rose pure and haunting, turning the dank cavern into a cathedral of sound.

When we finally emerged from the dark, damp underworld into the sunlight, our solemn mood was shattered by the sight of an outrageously fat groundhog. It sat like a furry emperor, feasting on an endless supply of snowflake crackers pressed upon it by adoring tourists. We stood watching, transfixed. The cave had given us mystery, history, and music; the groundhog gave us comedy. And we were happy.

September 30, 2025

The new ancient Tibetan village

We had set our hearts on exploring the countryside around Labrang, tucked away in the Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Word had reached me about an old Tibetan village called 八角古城, or Octagon Ancient Town, reputed to be a mysterious relic of history. In Tibetan it is known as Yungdrung Kar, or “Swastika City.” Unlike your usual circular or square layout, this one is designed as a hollow cross, with thirty-six angles and eight mounds. Seen from above, the pattern resembles the Buddhist “卍” symbol. How intriguing! Naturally, I was sold before I even got there. So, with great anticipation, we rented a car and set off.

Alas, reality is never quite as obliging as imagination. What awaited us was less “mysterious ancient town” than “architectural crime scene.” China, as I’ve noticed, has a habit of producing “new” ancient towns. This octagon-shaped village may indeed boast a venerable history, but what you see today are drab concrete houses devoid of rustic charm or any charm at all. The old timber and stone dwellings had long since been bulldozed. Many families offer home-stays, though why anyone would wish to linger in such an ugly place? The only sight that warmed me were yak-dung cakes drying on the walls.

The mud wall encircling the village, said to date back 1,300 years, is its one true relic. But mud, being mud, tells no tales. How to know which lumps are ancient, and which are fresh from last year’s repairs?

The big “attraction” was a raised platform promising a panoramic view of the octagon below outside the village. I declined with some stubborn dignity, preferring the open grasslands nearby. The girls dutifully climbed up while I strolled on the grassland.

My daughters returned, grumbling that the entire place was a fraud. I countered that this was precisely the spirit of adventure: things seldom unfold as planned. Our next stop—White Rock Cliff—redeemed the day magnificently. Ah, the joys of travel: disappointment and delight, served up in equal measure.

September 23, 2025

My former helper

Xiaohong has always been much more than a domestic helper. For over ten years she worked with our family, and in that time we grew close as sisters, helping each other weather life’s ups and downs. After she returned to her home village to marry, we never lost touch. Several times, she even brought her little boy along to our gatherings, folding him naturally into our circle of friends.

Yesterday, Mei, my elder daughter, (the younger one is travelling in Sichuan, on her way to meet us in Lanzhou) and I arrived from London at dawn and went straight to her village outside Langfang in Hebei. We spent a joyful day and night together—chatting, laughing, sampling the exercise machines in the square, and touring the village perched on her electric tricycle. Xiaohong and I are very different in temperament, yet one thing binds us: we both love to laugh, loud and wholehearted. Yesterday we laughed our teeth off, recalling old stories. She has a mischievous way of twisting foreign words into Chinese: my former sister-in-law Sharon once became xiaren (“shrimp”), while bonjour morphed into ben zhu (“stupid pig”).

Now her life is quieter. While her husband works in Beijing during the week, she tends her garden, raising vegetables for her own table, and spends hours studying Buddhist texts and chanting. Ever since she first met my handsome younger brother in Beijing and developed an interest in Buddhism, her devotion has deepened. Over the past decade she has become a devout believer, radiating a serenity that seems to satisfy her completely. I rejoice in her contentment. And already my daughters and I are scheming ways to bring her to England one day, so we can share in her laughter once again on our side of the world.