Chris Gavaler's Blog, page 15

February 20, 2023

Coloring Rage (part 3 of 2)

As part of my wandering research into Marvel’s use of the white supremacist supervillains Sons of the Serpent, I posted a two-part discussion of a 1991 Avengers story warning against Black anger after the Rodney King beating.

As my comics analysis has grown increasingly color-oriented, this third of the intended two installments focuses on colorist Christie Steele — whose complete color code art for Avengers #341 I recently found at comicartfans.com. (Rob Tokar colored #342, but his color code art, like the vast majority of color code art, can only be inferred from the published comic.)

#341-2 features the fifth appearance of the Sons of the Serpent, what Stan Lee intended as a fictional counterpart of the KKK when he co-created them in 1966. In this iteration, the villains are led by Leonard Kryzewski, a minion retconned into the group’s 1975 appearance. Not surprisingly, Steele assigns Kryzewski White skin and yellow hair, implying northern European descent.

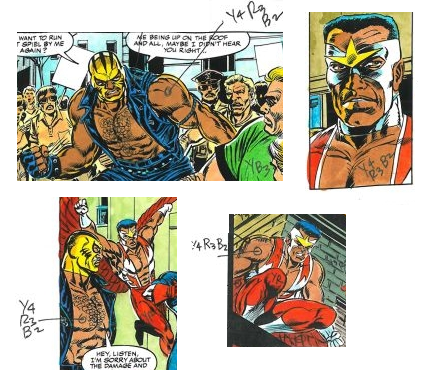

Steele assigns the same combination to a male figure in the next panel:

The sameness of penciller Steve Epting and inker Tom Palmer’s line art emphasizes the sameness of the White characters’ skin color. The first time I looked at the pairing, I briefly mistook the two to be the same figure — an unintentional recurrence effect that attention to other visual details eliminates.

After assigning most of Kryzewski’s group yellow hair and beige shirts, Steele gives other figures in the crowd the same combination, again visually blurring White people of opposing political stances. Since it defies probability that a dozen figures would all be wearing shirts of different design but identical color, the only naturalistic explanation is that the sameness is due to some quality of light.

Though Steele’s White people, whether White supremacists or not, visually combine, Steele attempts to differentiate non-Whites.

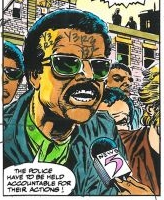

The newscaster has Black skin, labeled on Steel’s color code pages as Y4R3B2, meaning 75% yellow, 50% red, and 25% blue on off-white paper. Rage and Falcon receives the same codes throughout the issue too

But unlike the coloring of skin in previous decades, Steele provides some vacillation.

The first figure interviewed in the crowd of protestors appears to be Black, but Steele assigns the majority of his face Y3R3B2, creating a lighter brown that subtlety contrasts two Black faces in the background on either side. Steele also colors one side of his face a yellow that creates the naturalistic effect of a specific light source, presumably a late afternoon sun.

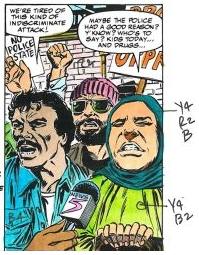

The next panel features three figures: a man with White skin in the center, a woman with White skin on the right, and a man with an ambiguous combination of brown and gray on the left.

Steele’s color codes art is ambiguous too. Some codes are written directly over colored areas, others are connected by arrows from the white margins, and some codes are missing — presumably with the assumption that the printer would interpret them from the colors themselves. Though her medium is identified as “colored pencils,” Steele may have worked with a brush, producing shapes of non-uniform color unlike the later printed art. In the case of the ambiguous figure, Steel’s original coloring appears more brown and therefor more naturalistic than in the published version.

The published version also recalls the taupe skin of Black characters used during earlier decades, including for Bill Foster introduced in the first Sons of the Serpent story in1966.

Where a 1966 colorist assigned the Sons of the Serpent’s first victim, Mr. Gonzales, White skin, Steele appears to designate the protester as Latino using the formerly Black-denoting taupe. The discordant color is more prominent in a riot scene near the end of the issue, with an apparently Latino man in a short-sleeve shirt throwing a rock; his taupe arm contrasts the Black figure in the background drawn directly below.

Where taupe designated Blackness in the 1960s, here the slightly evolved but still essentially limited color technology repurposed the color to designate an additional ethnic group.

Returning to the three figures in the earlier crowd panel, Epting pencils the third in a headscarf, presumably implying that she is Muslim. Though Epting could intend her closed eyes and gripped hands to suggest prayer, Nicieza instead scripts an unrelated defense of the police: “Maybe the police had a good reason? Who’s to say? Kids today …” Rather than assigning her Black or possibly Latina-associated taupe skin, Steele uses White skin, relying on the headscarf to differentiate her from the White man behind her.

The mixed-race superhero Silhouette poses a similar challenge. Nicieza and artist Mark Bagley introduced the character a year earlier in New Warriors #2 (August 1990), indicating that her father was Black and her mother Cambodian.

The six members of the New Warriors appear in a bottom banner on the cover of Avengers #341, with the Black character Night Thrasher’s brown skin juxtaposed with Silhouette’s taupe skin, revealing that taupe is not Latino per se, but a color generally designating an ethnicity outside a Black/White dichotomy.

When Silhouette appears for the first time in the interior art, Epting draws her stopping a Black man from throwing a bottle during a riot. Steele assigns her skin neither Black nor taupe, but a yellower brown not previously used (or identified in the color codes).

When Silhouette appears for the first time in the next issue, Tokar assigns her and Night Thrasher the same Black as Rage in the preceding panel.

But when she appears later in that issue, her taupe skin instead contrasts Rage.

The fluctuations, whether intentional or unintentional, could be understood as a reflection of the character existing outside of a clear racial division. They might also reflect the colorists’ attempts to use the highly limited technology more naturalistically, since actual skin colors fluctuate with changes in light.

For one page in #341, Steele assigns Falcon and Rage’s grandmother identical maroon skin in multiple indoor images.

In #342, an unnamed Black teenager vacillates between shades of brown in consecutive panels. Falcon even appears in one panel with inexplicably green-brown skin.

Even if all of the fluctuations are errors (by the color artists or by color-dividers later in the production process), the variations in skin color correlate with Marvel’s expanding depiction of racial and ethnics categories. They also reveal the inadequacy of 1991 printing technology to represent complex racial categories — and therefore to represent race generally.

Since color code art is pretty rare, I’ll conclude with Steele’s 22 pages:

February 13, 2023

Rodney King Rage (part 2 of 2)

Last week I began this two-part post on the Black superhero Rage and his use in an Avengers story responding to the beating of Rodney King in 1991. The first issue begins with a newscaster’s captioned voiceover: “The videotape of what has been dubbed ‘The Carmello Clubbing’ has been burned into the collective mind of New Yorkers — — and their opinions of the matter are as incendiary as the act itself!”

A man (later identified with the Polish last name Kryzewski) declares: “Punks like that deserve what they get! All them types do! City’s become a sewer since all your types showed up!”

Rage leaps down from a rooftop and challenges Kryzewski and his group—all given identical yellow hair by colorist Christie Scheele. After the group disperses, Rage speaks into the news camera:

“Cops got a lot to answer for. The ‘hood’s scared. Trust goes out the window, you know. We want to feel like the police are protecting us, not clubbing us down in the street.”

Later in the Avengers training room, Falcon explains to Rage: “The Avengers, as a concept, aren’t about dealing with problems of this kind.”

When Rage complains, “You don’t remember what it’s like to be a suspect just cause of the color of your skin!” Captain America responds: “I don’t think that’s very fair, son.”

Falcon: “Things aren’t always so black and white — –no pun intended — — age and experience have given me patience and tolerance.”

After Rage storms out, Captain America asks Falcon: “He has so much anger in him – where does it come from?”

“Same place as it all does, Steve – from what’s inside and what’s outside …”

Elsewhere, another Black superhero, Dwayne Taylor, AKA Night Thrasher (introduced December 1989, one month before Rage) trains with his Black father figure, Chord, echoing the Falcon’s attitude:

“Is there really that much I can do about it, Chord? […] I mean, how do I know who’s right and who’s wrong?”

Meanwhile Kryzewski, with the help of an unknown benefactor, re-forms the Sons of the Serpent, a “Radical hate group,” last seen in The Defenders #25 (July 1975). The retconned Kryzewski was arrested then for: “Aggravated assault. Inciting to riot. Attempted man-slaughter. Illegal possession of firearms,” but apparently wasn’t convicted given the fourteen years between publication dates—which would mean Rage was born the year the Sons of the Serpent attempted to start a genocidal civil war against Black Americans. Given the ambiguous nature of time within the Marvel universe though, the coincidence probably doesn’t reflect an in-world fact.

When the Sons of the Serpent incite a riot by challenging protestors outside a Brooklyn police district (“The time has come t’ eat the insects which are burrowing under the White skin of America!”), Night Thrasher’s team, the New Warriors, divide the two sides, with the Black female Silhouette chastising a Black man for throwing a bottle at the Sons:

“Now why don’t you calm down before you make matters worse?”

Soon Night Thrasher is responding with near homicidal force (“Because of my skin color they want to kill me!”), but only because the Sons’ secret benefactor is revealed to be Hate Monger—not the human Adolf Hitler clone from elsewhere in the Marvel universe but a new and apparently supernatural entity psychically intensifying and feeding from displays of hatred. (Nicieza also scripts him singing the Rolling Stones songs “Sympathy for the Devil” and “Shattered.”)

As the scene spills into Avengers #342 (December 1991), the Avengers arrive, making matters worse. Captain American eventually chastises the New Warriors:

“This is a matter best left to the police and community leaders!”

As far as the Rodney King character, even Rage’s grandmother agrees: “maybe the police were wrong for what happened to him, but how does fighting them solve the problem?”

When the four Avengers find the Sons’ headquarters and effortlessly defeat them, Captain America declares: “They weren’t very skilled, but better to stop it here and now before their hate group could grow.”

Falcon adds: “Kind of a shame to think that there are people out there who would agree with these clowns!”

But then Hate Monger returns, followed by Rage and the New Warriors, who Hate Monger incites into new passion before draining their energy. Only Rage struggles to keep fighting:

“You’re the reason my friend was clubbed down in the street. You’re the reason me and my people have been put down all our lives!”

Captain America: “Rage—stop! You’re giving him exactly what he wants! […] Stopping the Hate Monger won’t stop that madness, son! It has to start inside each of us. It has to start inside of you.”

In the page gutter between consecutive panels, Rage changes his mind: “You’re right … … There’re better ways to fight people like the Serpents .. than giving them exactly what they want …”

Hate Monger is disappointed, but promises to return when Rage’s resolve fades.

Captain America: “Rage—what you did—letting go of your hatred—it took a lot of courage.”

However, having learned that Rage is only fourteen, Captain America explains he can’t remain on the team. Rage is content with the decision: “maybe I won’t need to be Rage anymore – ‘cause there’ll be nothing to rage about!”

Nicieza’s allegorical script offers several messages. Here are the first few that come to mind:

avoid violence,trust the police and others in authority, don’t judge police officers videotaped beating a darker skinned man, racists are small in number and ineffectual if ignored, all racial animosity is equivalent,national racial problems can only be addressed at the individual level.Most of these opinions are expressed by a White man wearing an American flag, but I find the use of Falcon (included exclusively because he is Black), other Black superheroes (the equivocating Night Thrasher and scolding Silhouette), Rage’s grandmother (a trope of Black wisdom), and (the reformed and immediately retired) Rage more unsettling. As Nicieza’s newscaster said: “opinions of the matter are as incendiary as the act itself!”

But I’m most unsettled by a less direct message conveyed in the final color art.

The second issue’s one-page admonitory epilogue features a crowd of Black citizens gathered in an unnamed City Hall listening to a charismatic Black speaker:

“We can’t allow ourselves to be oppressed any longer! For centuries we have been placed in a position of inferiority and called a minority. They must feel the whip as we have! They must swing from the hangman’s noose as we have! Segregation equals degradation. We won’t be degraded anymore! There’s so much to be angry about, isn’t there? Yes, there is! A lot to fight against, isn’t there? Yes, there is! A lot to hate … isn’t there?”

The final panel reveals the speaker to be Hate Monger—now with Black features. For the previous issue, Scheele had given the character White skin, but for #342 colorist Tob Tokar instead uses an inhuman shade of yellow distinct from the skin color of White characters. On the cover, Hate Monger’s skin is a more overtly non-human grayish blue. Tokar’s revision of Scheele’s initial choice also evokes Scheele’s avoidance of White-signifying skin color for the White police officers beating the Rodney King character in the opening splash page.

It seems Hate is more at home in Black skin than in White.

February 6, 2023

Rodney King Rage

I wasn’t expecting this topic to be timely. When I started drafting this post last year, it was one in a continuing sequence about Marvel’s KKK-based supervillain group Sons of the Serpent introduced in 1966. Marvel resurrected them 25 years later to allegorize their political views about the 1991 beating of Rodney King. I can’t think about the King now without thinking about the disturbingly similar video of Tyree Nichols released last week.

It’s 32 years later, and I hope Marvel doesn’t resurrect the Sons of the Serpent again. The simplistic moral universe of mainstream superhero comics is not ideal for trying to address the complexities of police brutality in the continuing aftermath of Jim Crow. Marvel’s use of their their Black superhero Rage in 1991 is evidence of that.

Larry Hama and Paul Ryan created Rage in Avengers #326 (November 1990). The character was at least in part a critique of the Avengers, and so Marvel generally, lacking Black superheroes. Two issues later, he asks Captain America: “Why don’t you have any righteous African Americans in this outfit?”

“What about Black Panther and Falcon?”

“Panther went back to mother Africa. The man is millionaire royalty. He’s got entree into country clubs that wouldn’t let you past the parking lost. Falcon was around only because the Feds required you to meet equal opportunity standards… Now that you don’t have any minority Avengers, you start building a fancy mansion in the middle of a ritzy, lilly-white neighborhood!”

Hama’s dialogue doesn’t reference the 1982 Monica Rambeau Captain Marvel or the 1983 James Rhodes Iron Man, both former Avengers, but the fault is still relevant. Unfortunately, so is Ryan’s costume design, which reiterates the 70s trend of exposing more skin for Black male superheroes than for White male ones. Also, because Rage is actually a thirteen-year-old boy transformed, his character literalizes what Eve L. Ewing (education scholar and later writer of Ironheart) identifies as “the adultification of Black children” (Ewing 2021).

After Hama’s Captain America voices a color-blindness defense, “First off, nobody just walks in and gets to be an Avenger, no matter if they’re white, black, yellow, or green, for that matter!,” and then stops the other Avengers because there’s “been a terrible misunderstanding! Rage wasn’t attacking me, he was trying to make a point … … in fact a very valid point about perceptions!,” Rage is voted a “reserve substitute” “probationary Avenger” in the next issue. Falcon and Monica Rambeau are voted substitutes too, placing no Black heroes on the primary team–oddly reinforcing Rage’s original complaint.

Despite his probationary substitute status, Rage appears on eight more covers, including Avengers #342 (November 1991), his last as a team member. The two-issue story arc is memorable for other reasons.

On March 3, 1991, four LAPD officers beat motorist Rodney King with metal batons over fifty times while arresting him for felony evasion. Bystander George Holliday’s videotape of the beating was aired on CNN two days later and then on network news the next evening. A grand jury indicted the officers a week later. The trail was set for June, but a Court of Appeals granted a change of venue and reassigned the case to a new judge due to evidence of the initial judge’s bias (he secretly communicated to prosecutors: “Don’t panic. You can trust me.”).

Avengers #341 is cover-dated November 1991 and so would have been published in late September. Production times vary, but estimating a four-month norm, Fabian Nicieza scripted the story in May, well after news of the beating had broken but before the appeals court ruling.

Though Hama and Ryan had created Rage almost two years earlier, Nicieza’s use of the character and the reprisal of the White supremacist supervillains the Sons of the Serpent are a response to Rodney King. So is the unexplained reappearance of Falcon as a primary Avenger, making two of the five members Black. With the addition of Night Thrasher of the New Warriors, the #342 cover features three Black characters and two recognizably White ones.

I assume editor Ralph Macchio and editor-in-chief Tom DeFalco were involved in these decisions, especially since Nicieza, who was writing The New Warriors at the time, is credited as “guest writer,” with the previous writer, Bob Harras, returning after the two-issue arc. Falcon and Rage are replaced afterwards too, resulting in an all-White Avengers roster.

Penciller Steve Epting’s #341 splash page evokes the King video, with King’s fictional counterpart, Carmello Martinez, drawn on his knees surrounded by four police officers with raised batons. Inker Tom Palmer and colorist Christie Scheele contribute significantly to the image, rendering the majority of the White officers’ faces in a black that nominally denotes shadows cast by their police caps but connotes a metaphorical darkness. More than half of one face is so opaquely black it partly subverts the illusion of three-dimensionality. The officers’ legs are rendered the same, further challenging the naturalism of the overall image with the shapes of undifferentiated flatness. Where the White officers’ skin is exposed, the color is the white of the underlying page. In contrast, the face and figure of King’s shirtless counterpart is shaped by black contour lines and minimal crosshatching, with no black areas except for portions of his hair. His skin is a combination of brown and page-white.

Nicieza’s and Epting’s Black female newscaster narrates: “This was the scene two days ago as videotaped by an alert bystander.”

The Rage Wikipedia page identifies the superhero’s alter ego as “Elvin Daryl Haliday,” adding “sometimes misspelled ‘Holliday.’” I’m trying to track down where and when those “sometimes” occur, but I have to wonder whether the misspelling is an intentional allusion to George Holliday, the bystander who recorded King.

In the Marvel universe, Elvin (AKA Rage) and Carmello (AKA Rodney King) are best friends.

(More next week.)

January 30, 2023

What Race Are My Cartoons?

I was experimenting last year with a MS Paint technique that produced semi-naturalistic results. The last image in the file is dated September 7th — two days before my fall classes started.

This one is dated September 6th, three days before classes:

The digital process is both odd (I showed part of the process here) and painstaking (I suspect actual artists would just draw something with a fraction of the effort), so it’s not surprising that I didn’t carve time out of my semester for more of these.

I’m now well into my winter semester, and though I was hoping to develop some of these images into comics, not only are they time-consuming to make, I don’t have the skill to create two detailed images that seem to represent the same person. In comics-theory terms, I call that recurrence, and the more naturalistic two (or more) images are, the harder it is to produce the viewer perception.

That’s one of the reasons most works in the comics medium are drawn in a cartoon style. Not only is the simplification practical (fewer lines to draw), but the exaggerations also defines a character quickly and distinctly.

Style also involves line quality. I have a pet peeve against computer-graphic line art that looks like computer-graphic line art — I think because of the artificially perfect sameness of the line widths? So for me, creating a recurrent cartoon requires designing not only an easily reproducible set of lines to represent a simplified and exaggerated character, but also a line style that’s interesting apart from the subject matter.

I started with this:

Not sure if the top lines register as hair or a nun’s habit. The absence of a body doesn’t help to clarify. So I expanded, still emphasizing a quick gestural representational style.

Technically, those figures aren’t made of single lines but of double lines that together scissor out shapes from a black background (my MS Paint hacks are easy to demonstrate but hard to describe in words). I’ve also been experimenting with using layers of words as texture, which (for reasons I don’t understand) reveal/create hidden colors when layered:

I like the effect in other contexts, but not particularly here. The process is interesting though. To create the word textures (“text-ures”), I started by making colored shapes, unsure which I would convert later:

I wasn’t planning on keeping any colors, and though I needed literally any three as a step in the process, my unexamined choices don’t seem random. Brown is a skin color, auburn is a hair color, and vibrant green only makes sense in clothes. Though I probably have a vibrant green shirt somewhere in my closet, my own hair is dark brown, and my skin could be called beige (probably Type II on the five-part Fitzpatrick skin scale).

If I had been subconsciously imitating my own skin, I might have created this:

I have also been working on a next monograph tentatively titled “The Color of Paper: Representing Race in the Comics Medium,” which includes analysis of the paradoxically representational qualities of background colors. Looking again at the text-ured versions, the interior areas of the figures’ skin is literally the white of this digital background. But I’m not sure if viewers register that white as “White” skin:

To explore that ambiguity further, I changed to grayscale colors: black lines, dark gray shapes, light gray shapes. The combination often creates the impression of black-and-white photography: the figure exists in color (somewhere) but is depicted (in the image) as though actual colors have been converted to naturalistically corresponding grays.

What does that reveal about impressions of race and ethnicity? I’m not sure. Is this a White person with dark hair in a medium-dark dress?

Is this a Black person with white hair and a white dress?

I don’t know the answers — including whether different viewers experience the images differently. I just applied for summer research funding to conduct a study about those sorts of perceptions (hopefully to be included in “The Color of Paper”), but while I was trying to design a cartoon, my visual preference first fell on this combination:

Which I then tested to see if I could create new images with a recurrence effect for viewers (including myself). Is this the same person?

More recurrence attempts followed, plus a return to “text-ured” clothes and hair:

I also vacillated on skin. Should it be light gray or should it be the background white of the negative spaces within the black lines?

The light gray I think is racially/ethnically ambiguous since the color ranges of skin for White people and Black people overlap (in the center of the Fitzpatrick scale). The background white could suggest very light skin and so would be less racially/ethnically ambiguous — although I can cite examples of Black characters depicted in this style too.

So I kept experimenting:

I eventually settled on a final design: white hair, light gray skin, text-ured dress, and width-fluctuating black lines. I chose that combination in part because the interior light-gray shapes interact with the black lines, imperfectly filling the spaces and so leaving inconsistent white edges. I find that stylistically interesting both to create and to look at. The “text-ures” are also fun to warp in a way that suggests fabric to me, and leaving the negative space within the area of the hair adds a contrast to the other two approaches.

So what race is my cartoon?

I still can’t say. Light gray interiors make the figure ambiguous — at least when judging race and ethnicity by skin color alone. Facial features are at least as important, and when skin color is indeterminate, the significance of facial features rises accordingly.

But that’s a topic for another blog.

My co-author Leigh Ann Beavers and I wrote in our textbook Creating Comics: “You have a character. Now you need to know what it looks like from any point of view. Draw it fifty ties (yes, fifty!). You’ll be the world’s expert by the end of this exercise.”

I’ve not hit fifty yet, but I’m getting there.

Though, who knows, maybe I’ll go back to semi-realism again too. Here’s one of my first from last May:

January 23, 2023

Feminist Third Wave Rechristenings of Marvel’s Phase Four Superheroines (part 2 of 2)

Earlier this month I overviewed the Second Wave origins of Jane Foster, Carol Danvers, and Jenifer Walters. This week their characters transform even further.

Captain Marvel

Because Captain Marvel never became a popular character (Marvel published Captain Marvel only every other month before cancelling the series after #62 [May 1979]), Marvel allowed Jim Starlin to script and pencil the 1982 graphic novel Death of Captain Marvel, in which Mar-Vell dies of cancer.

Unlike the vast majority of superheroes whose apparent deaths are retconned as non-deaths, Mar-Vell is likely the only major Marvel superhero not to be restored after more than forty years. The editorial decision prompted Marvel to create a new character, presumably to maintain control of the trademark. Scripter Roger Stern and penciler John Romita, Jr. introduced Monica Rambeau in The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #16 (October 1982) who transforms into an unrelated superhero and adopts the name “Captain Marvel” with no apparent reference to Mar-Vell.

Though Third Wave feminism begins several years later (arguably when Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” in 1989), because Rambeau is a Black woman, she reflects the later shift away from feminism focused primarily on white women. The vast majority of Marvel’s female superheroes, however, remained white.

After featuring Rambeau in The Avengers during the 80s, Marvel changed the character’s superhero name multiple times, applying “Captain Marvel” to other characters (including briefly Mar-Vell’s son, Genis-Vel), before Carol Danvers (who had also undergone multiple name changes) was rechristened “Captain Marvel” in scripter Kelly Sue DeConnick’s and penciller Dexter Soy’s Captain Marvel #1 (September 2012).

Deepening Danvers’ claim to her new name, scripter Margaret Stohl further retconned Danvers’ origin beginning in The Life of Captain Marvel #1 (September 2018), revealing that the Kree device that Thomas scripted in 1969 and that Conway retconned in 1977 to have duplicated Mar-Vell’s powers in Danvers had instead awakened Danvers’ own powers inherited from her Kree mother who had defected and lived as an Earth woman.

Since Danvers’ assuming the name “Captain Marvel” left the name “Ms. Marvel” unused, editor Sana Amanat assigned scripter G. Willow Wilson and penciller Adrian Alphona to create Kamala Kahn in Ms. Marvel #1 (February 2014).

Like Amanat, Kahn is a New Jersey teenager of Pakistani immigrants. Because Kahn idolizes Carol Danvers, when her Inhuman superpowers emerge, she initially shapeshifts to look like Danvers (in the Ms. Marvel costume introduced by artist Dave Cockrum in 1978) before assuming an appearance of her own (which included the scarf of John Buscema’s original 1977 design).

Later the same year, Jane Foster assumed the title role in scripter Jason Aaron’s and penciller Russell Dauterman’s Thor Vol. 4, #1 (Oct. 2014), which replaced the previous Thor series that had featured the original character (though Thor’s Donald Blake identity had been discarded since 1983).

After Thor’s hammer chose Foster, she assumed the name “Thor” when in her superhero form, and Thor became known by the full name “Thor Odinson,” retconning “Thor” as having always been an abbreviation of that full name. Aaron’s Foster now calls him “Odinson,” explaining to him as she succumbs to cancer:

‘There must always be a Thor.’ That’s what I said right before I lifted Mjolnir and was transformed for the first time. I was honored to carry that mantle for a while. Honored that you bestowed upon me your own name. But it’s time you reclaimed who you are. […] There must always be a Thor. And now … once again … it must be you. […] The hammer made me the Thunderer. But not you. You did that yourself. Odinson, look at me …”

Foster remains the title character until Mighty Thor Vol 2 #706 (June 2018), when she dies (though soon resurrected), and Thor Odinson returns beginning Thor Vol. 5 #1 (August 2018).

She-Hulk

After her initial series, The Savage She-Hulk, concluded on #25 (March 1982), Jennifer Walters appeared in multiple team titles and eponymous titles, including: The Sensational She-Hulk #1-60 (May 1989-February 1994), She-Hulk #1-12 (May 2004-April 2005), She-Hulk Vol. 2 #1-38 (December 2005—April 2009), and She-Hulk Vol. 3 #1-12 (April 2014-April 2015).

All-New Savage She-Hulk #1-4 (June 2009-September 2009) features a different character (a time-traveling Hulk descendant from an alternate future timeline) in the title role. Marvel had also introduced Red Hulk in 2008 and Red She-Hulk in 2009, expanding “Hulk” as a category rather than as a proper name.

When Walters assumed the title role in Mariko Tamaki’s Hulk Vol. 4 #1-11 (February 2017-December 2017), it was the first time she was featured in a series without She-Hulk in its title, and also the first time a Hulk title did not feature Banner, who at the time was dead (and not yet resurrected).

The trend continued with Totally Awesome Hulk #1-23 (February 2016-November 2017), which featured Amadeus Cho (who removed the Hulk from Banner and placed it himself) in the title role, after which the original character was known as “Banner Hulk,” appearing next in Generations: Banner Hulk & Totally Awesome Hulk #1 (October 2017).

As with Jane Foster who is no longer called “Thor” (Foster is currently “Valkyrie,” another superhero name and identity with a complex history I won’t try to cover here), Jennifer Walters is no longer called “Hulk.” Reverting back to her earlier name, Walters was next featured in She-Hulk #159-163 (January 2018-May 2018) and currently in She-Hulk Vol. 4 beginning with #1 (March 2022). The latest title coincides with the Disney+ series She-Hulk: Attorney at Law, which premiered in August 2022. She-Hulk Vol. 4 #12 is scheduled to be released in April 2023.

Reboots

The MCU versions of Foster, Danvers, Walters, and Kahn are reboots of these originals, condensing and altering their complex comics and inconsistently feminist histories.

In all four cases, the original superhero name (Hulk, Thor, Captain Marvel, Ms. Marvel) began as a proper noun that referenced one specific (and usually male) character, before the name later became either a transferable title referencing one person (of any gender) at a time or a kind of category referencing two (or more) people (of any gender).

“Hulk” originally meant only Banner Hulk, but now “Banner Hulk” means only Banner Hulk, and “Hulk” means multiple people including both Banner Hulk and Jenifer Walters.“Thor” originally meant only “Thor Odinson,” but now “Thor Odinson” means only Thor Odinson, and “Thor” can mean different people including formerly Jane Foster and currently Thor Odinson.“Captain Marvel” originally meant only Mar-Vell, but now “Captain Mar-Vell” means only Mar-Vell, and “Captain Marvel” can mean different people including formerly Mar-Vell and currently Carol Danvers.“Ms. Marvel” originally meant only Carol Danvers, but now “Ms. Marvel” can mean different people including formerly Carol Danvers and currently Kamala Khan.While the trend is toward gender-inclusive names (with “Hulk,” “Thor,” and “Captain Marvel” formerly male-specific but now gender-neutral), “Ms. Marvel” was and remains female-specific. That’s an artefact of the title originally meaning roughly “female version of Captain Marvel,” just as “She-Hulk” meant something like “female version of Hulk.”

Oddly in the MCU, Carol Danvers never used the name “Ms. Marvel,” and, even more oddly, neither does Kamala Kahn. Ms. Marvel is the title of a TV series whose main character never adopts a permanent superhero name. So the MCU includes Ms. Marvel but not Ms. Marvel.

Marvel Entertainment also chose to keep Jenifer Walters superhero name “She-Hulk,” despite Tamaki’s 1917 Hulk comics influence on the TV series. As a result, the MCU is arguably a feminist wave behind Marvel Comics.

January 16, 2023

MLK

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity. But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition. In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men — yes, Black men as well as white men — would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds. But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice. We have also come to his hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quick sands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children. It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. 1963 is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges. But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone. And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back. There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, when will you be satisfied? We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: for whites only. We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream. I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our Northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends. So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal. I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today. I have a dream that one day down in Alabama with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right down in Alabama little Black boys and Black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today. I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together. This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day. This will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning: My country, ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrims’ pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring. And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true. And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania. Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California. But not only that, let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring. And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, Black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: Free at last. Free at last. Thank God almighty, we are free at last.

January 9, 2023

Feminist Second Wave Origins of Marvel’s Phase Four Superheroines (part 1 of 2)

With the death of Black Widow and the supervillaining of Scarlet Witch, the MCU currently features only four major female superheroes, all recently introduced.

Captain Marvel (2019), one the last films in Marvel Entertainment’s so-called Phase Three projects, fully introduced Carol Danvers. Phase Four featured Jane Foster in Thor: Love and Thunder (2022), Kamala Khan in the Disney+ series Ms. Marvel (2022), and Jenifer Walters in the Disney+ series She-Hulk: Attorney at Law (2022).

I’m tempted to compare the MCU superwomen with the Fourth Wave of feminism, in part because Fourth Wave is largely a continuation of the Third Wave, much as Marvel’s Phase Four is a continuation of its Phase Three. But Phase Four owes far more to Second Wave feminism.

Though feminist waves are not dated consistently, Second Wave is typically understood to span from the early 1960s (President Kennedy signed the Equal Pay Act into law in June 1963) through the 1970s and 1980s, stopping before the 1990s. The male superheroes Hulk, Thor, and Captain Marvel, as well as two of the three female characters who later assume those names, originate in early 1960s comics, but few reflected any feminist attitudes during their first incarnations.

Banner, Blake, and Mar-Vell

The Incredible Hulk #1 (May 1962), cover-dated five months after the premiere of Fantastic Four, introduced the second superhero title under publisher Martin Goodman’s newly renamed Marvel comics. After caught in the radiation of a Gamma bomb detonation, Bruce Banner transforms into a “man-monster” with a distinct and separate identity.

Stan Lee scripts a pursuing soldier: “Fan out, men! We’ve got to find that – that Hulk!” Lee’s narrator responds: “And thus, a name is given to Bruce Banner’s other self, a name which is destined to become – immortal!”

Marvel followed the Hulk with Spider-Man in Amazing Fantasy #15 (August 1962) and Thor in Journey into Mystery #83 the same month. For Thor, Lee and penciller Jack Kirby created Don Blake, a doctor with a disability (Lee uses the adjective “lame”) who discovers an enchanted cane that transforms into a hammer with the etched explanation: “Whosoever holds this hammer, if he be worthy, shall possess the power of … THOR.” The hammer also transforms Blake’s body (Kirby draws muscular bare arms and long wavy hair) and clothing (Kirby combines superhero cape and briefs with nominally Nordic boots and winged helmet). Despite the physical changes, Blake’s consciousness remains. After reading the inscription, he remarks: “Thor!! The legendary god of thunder!! The mightiest warrior of all mythology!! This is his hammer!! And I – I am Thor!!!”

Lee was apparently influenced by the pseudonymous Wright Lincoln‘s “Thor, God of Thunder” published in Fox Comics’ Weird Comics #1-5 (April 1940–August 1940), in which the Norse god decides: “I will invest an ordinary mortal with my great powers.”

The absence of a separate Thor grew increasing complex in the Lee and Kirby stories, with the transformed Blake visiting Asgard and interacting with characters who understand him to be the actual son of Odin, including Odin himself. Lee also scripted the character’s speech in faux Old English, further blending Blake and Thor. Eventually, Lee and Kirby retconned an explanation, revealing in Thor #159 (December 1968) that Odin had erased Thor’s memory and created the mortal identity of Don Blake: “Yet ever were thou son of Odin … though thou knew it not! Twas I who placed thy hammer in an earthly cave … so thou wouldst one day find it! … And find it though didst … when thy lesson had been learned!”

One of the last of Lee’s co-creations, Captain Marvel first appeared in Marvel Super-Heroes #12 (December 1967).

An unrelated Superman-derivative character of the same name had premiered in Fawcett Comics’ Whiz Comics #2 (February 1940), prompting DC to sue for copyright infringement.

When the legal dispute was finally settled in 1953 and Fawcett agreed to cease publishing the character, the market for superhero comics was decimated.

In 1966, after DC and Marvel had revitalized the genre, a third company, M.F. Enterprises, released a new Captain Marvel title featuring an unrelated superhero to capitalize on the now popular Marvel Comics name. Marvel responded by introducing their own Captain Marvel to secure a trademark claim. Unlike the Fawcett original, Lee and penciller Gene Colan’s Captain Marvel was literally a captain (in the military of the alien Kree race) with the last name “Mar-Vell,” which human characters interpret as “Marvel.” Gil Kane updated his costume in Captain Marvel #17 (October 1969).

Foster, Danvers, and Walters

Lee, Kirby, and co-scripter Larry Lieber (Lee’s brother) introduced Jane Foster as a love interest in Thor’s second issue, Journey into Mystery #84 (September 1962), in a variation on the superhero-formula triangle relationship established by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster in Action Comics in 1938. The Clark-Kent-like Dr. Blake secretly pines for his assistant nurse, who, fooled by Blake’s double identity, secretly pines for him and yet also for the hypermasculine Thor. Like Siegel and Shuster’s Kent, Lee and Kirby’s Blake feigns cowardice, explaining his absence during Thor’s heroics: “I was … ahh …. hiding behind the execution wall! I figured it was he safest place to be!” Foster expresses her disappointment in a thought bubble: “Hiding! Golly, why couldn’t you be brave and adventurous like — Thor!”

After Lee scripted Captain Marvel’s premiere, Roy Thomas took over the series, collaborating with Gene Colan when creating Carol Danvers in the subsequent issue, Marvel Super-Heroes #13 (March 1968). A U.S. general introduces her: “This is Miss Danvers! Man or woman, she’s the finest head of security a missile base could want!” Though the professional position of authority contrasts Foster’s assistant role when introduced six years earlier, Danvers narratively still serves as a Louis-Lane-derivative love interest, attracted to Captain Marvel while unaware of his secret identity when he poses as an earth man she is indifferent to. Mar-Vell also spends a lot of his superheroic time rescuing her.

As the women’s rights movement gained prominence in the early and mid-70s, Marvel introduced a range of female characters (Valkyrie, The Cat, Shanna the She-Devil, Satana, Tigra, Colleen Wing, Misty Knight, Storm, Red Guardian) and heightened older ones. A re-costumed Black Widow received her own series beginning in Amazing Adventures #1 (August 1970), and scripter Chris Claremont transformed Marvel Girl into the far more powerful Phoenix in Uncanny X- Men #101 (October 1976).

In Ms. Marvel #1 (January 1977), scripter Gerry Conway and penciller John Buscema reconceived Carol Danvers as the editor of Women Magazine, an allusion to Gloria Steinman’s Ms. magazine launched in 1972. Conway’s Danvers explains her career change: “Captain Marvel’s appearance at the Cape – and my inability to capture him – just about destroyed by security field career. I kept trying to hold it together, until I finally went back to my first love – writing.”

Danvers also suffers from migraines and black-outs, becoming a female version of Captain Marvel (Buscema’s costume design reproduces Mar-Vell’s, except with bare legs, stomach, and back) who is equally unaware of her double identity. When asked whether she has a name, she answers: “I don’t think I do!”

Though the title prefix “Ms.” was first proposed in 1901, and activist Sheila Michaels had been promoting it since 1961, it did not gain popular attention until Michaels was interviewed on a New York radio show in 1969, and Steinman and organizers of the Women’s Strike for Equality began promoting it the following year (Zimmer 2009). Danvers adopts “Ms. Marvel” by the end of her first adventure, and Conway later retcons an incident from Captain Marvel #18 (November 1969) in which Thomas had scripted Mar-Vell rescuing Danvers from an exploding alien device, now revealing that Danvers had absorbed his alien abilities as a result.

Dave Cockrum redesigned her costume for Ms. Marvel #20 (October 1978).

Marvel introduced the premise of Jane Foster becoming Thor a year later in What If #10 (August 1978). Scripter Don Glut described the series as “just one-shots” that came about at parties: “We’d get a little bit happy and someone would say something like, “Hey! What if Spider-Man had two heads?” (Imageantra). Glut recalled the question and eventual issue title “What If Jane Foster Had Found the Hammer of Thor?” emerging from such a conversation with Rick Hoberg, who later penciled the story. Glut’s recollection also implies that the notion of a female Thor was as outlandish as a two-headed male superhero.

For What If #7 (February 1978), Glut and Hoberg had imagined that three different characters, including Spider-Man’s first girlfriend, Betty Brant, “had been bitten by the radiative spider.” Spider-Girl, the lone female variant, initially avoids using her super-strength but then accidentally kills a criminal and so chooses to end her superhero career.

Hoberg’s female Spider costume includes bare legs, arms, shoulders, upper chest, and cleavage, but he draws Thordis in a costume closer to Kirby’s original (her legs are bare, and two of the previously decorative chest circles are now protruding breast armor).

The Jane Foster What If issue title also avoids the question of identity by focusing on Foster finding the hammer rather than on her becoming Thor. As originally scripted, when Lee’s Blake transformed, he vacillated ambiguously between two identities. Glut scripts Foster to draw a different conclusion: “Obviously, if I’ve got Thor’s powers now, I’m not really Jane Foster … so maybe I should call myself something else. I remember from nursing school a Norwegian girl named Thordis; that has a nice sound to it. All right, then … that’s what I’ll call myself – Thordis!!”

Ultimately, Odin requires Jane to “surrender” the hammer because “ownership of Mjolnir hath ages ago been decreed by fate.” After the hammer transforms Blake into Thor and Odin restores his memory, Thor is united with his Asgardian love interest, Lady Sif.

Odin has also transformed Foster into a goddess as reward for her service, and she weeps over the “cruel joke” of being “made an immortal only to suffer an eternity — — separated from the man I love.”

She asks to be made mortal again, but Odin instead proposes marriage to her, which she accepts, realizing in the concluding full-page panel “that those very qualities she admired and loved in the mortal Don Blake — — are also to be found in the father of the immortal Thor.”

Jennifer Walters premiered two years later in The Savage She-Hulk #1 (February 1980). As with Captain Marvel twelve years earlier, Stan Lee and penciller John Buscema created the character for copyright reasons. The TV series The Incredible Hulk began airing in 1977, and Marvel feared that producer Kenneth Johnson, who had created the spin-off series The Bionic Woman from a character originally introduced on The Six Million Dollar Man, would create a female Hulk.

Acknowledging the Marvel character, Johnson later explained in an interview that “we had plans for Banner’s sister having a disease where only the blood of a sibling would save her life. We weren’t going to do a bra-popping She-Hulk, but we were going to do a woman Hulk who was crazy and scary and dangerous” (inverse.com). The character would have appeared in the fifth season—but the series was cancelled mid-season in 1982, two years after Marvel debuted their version of “a woman Hulk.”

In Lee’s script, Walters is Banner’s younger cousin, a retconned character who Banner calls “Little Jen” but who he hasn’t seen since before he “quit med school for nuclear physics,” so prior to The Incredible Hulk #1. Walters is also a “big time criminal lawyer” with “Jennifer Walters ATTN” on her office door.

Because she planted a rumor about having murder evidence, she is shot by a hitman while leaving her office, prompting Banner to perform an emergency transfusion. Walters reflects in the final panel: “The blood transfusion must have caused it!”

Like Banner whose transformed self was named descriptively, Walters is described by an onlooker: “It’s a girl! But — look at the size of her! Her skin! It’s – it’s green! It’s like — she’s some kind’a She-Hulk!” She adopts the name: “whatever Jennifer Walters can’t handle – the She-Hulk will do!”

Though “Hulk” remains a proper name referencing Banner’s alter ego, like the 1974-78 TV series Police Woman or DC’s “Lady Cop” in 1st Issue Special #4 (July 1975), “She-Hulk” distinguishes the character as a female variant of a nominally ungendered but implicitly male category.

(Next week: Third Wave Rechristenings!)

January 2, 2023

Indian Diptychs

I’m typing this on January 2nd, at the start of a final day in Kochi, India, before flying tonight and all day tomorrow to arrive back home tomorrow on January 2nd. That temporal diptych is made possible by the gutter of the international date line.

The diptychs below are divided by no gutters, but accepting my own default right-to-left and top-to-bottom reading paths, each is sequenced and so is in the comics form. If this blog counts as an occasional publisher of comics, they’re in the comics medium too, and so are webcomics, as well as photocomics. Most are not (or at least not primarily) narrative though, since each juxtaposition suggests different kinds of visual and thematic relationships.

December 26, 2022

India and the First Superhero

When I began researching superheroes over a decade ago, one of the earliest texts I found was an obscure British penny-dreadful about Spring-Heeled Jack — an orientalist character supposedly born in India. Like other orientalist texts, this one has absolutely nothing to do with any actual place. But since I am currently traveling in India with my family, I thought I would schedule a post from the Spring-Heeled Jack section of my 2013 article “The Imperial Superhero,” later revised into a chapter for Superhero Comics (2017).

Summarizing the postcolonial critique of nineteenth-century British literature, Ania Loomba declares “no work of fiction written during that period, no matter how inward-looking, esoteric or apolitical it announces itself to be, can remain uninflected by colonial cadences” (2005: 73). The claim applies particularly to the body of literature that produced the pre-comics superhero. Emerging as a sub-genre of juvenile literature, the character type is an amalgamated product of several pre-existing and overlapping genres—juvenile fantasy, adventure, science fiction, detective fiction—each with its own nineteenth-century colonialist ties.

Daphne Kutzer laments how scholars too often ignore children’s texts and their role in forming a “national allegory,” texts which from the late nineteenth century to early World War II “encourage child readers to accept the values of imperialism” (2000: xiii). Jo-Ann Wallace identifies “the rise of nineteenth-century colonial imperialism” with “the emergence of … a ‘golden age’ of English children’s literature,” a genre of “primarily … fantasy literature” (1994: 172), with the term “imperialism” coming into popular use during this fantasy age’s middle decade of the 1890s (Eperjesi 2005: 7). Edward Said also cites “fantasy” as a primary example of “generically determined writing” that produces and shares orientalism’s “cumulative and corporate identity” (1978: 202). Fantasy is especially conducive to imperialist projections, as Elleke Boehmer emphasizes “the way in which the West perceived the East as taking the form of its own fantasies” (2005: 43). When defining “colonial literature,” Boehmer offers H. Rider Haggard’s 1885 lost world fantasy adventure King Solomon’s Mines as her representative example of a novel “reflecting a colonial ethos” and “the quest beyond the frontiers of civilization” as a defining motif of all colonial literature (2). Jeffrey Richards views adventure literature as “not just a mirror of the age but an active agency” that energized and validated “the myth of empire as a vehicle for excitement, adventure and wish-fulfillment through action” (1989: 2–3). John Rieder similarly observes how “the Victorian vogue for adventure fiction in general seems to ride the rising tide of imperial expansion,” while “the period of the most fervid imperialist expansion in the late nineteenth century is also the crucial period for the emergence of” science fiction (2008: 4, 2–3). Patricia Kerkslake reads science fiction as an exploration of “the notion of power formed within the construct of empire, especially when interrogated by the general theories of postcoloniality” (2007: 3). Caroline Reitz applies a parallel approach to detective fiction, reading the figure of the detective “as a representative of the British Empire” who rose in popularity as Victorian national identity shifted “from suspicion of to identification with the imperial project” (2004: xiii). Dudley Jones and Tony Watkins critique not only the adventure story for its associations “with colonizing pioneers and ethno-centric notions of racial superiority” (2000: 13), but the multi-genre figure of the hero whose “notions of exemplary value … influenced children’s literature through the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth” and whose “moral virtues … were always articulated through the ideological frameworks of gender, imperialism, and national identity” (4). By combining these genres, the superhero is a depository and melding point for a multitude of imperial tropes and attitudes.

The earliest known manifestation is Spring-Heeled Jack who, paralleling Britain’s expansion from an empire of chartered entrepreneurs to one of direct governance, appeared in “at least a dozen plays, penny dreadfuls, story paper serials, and dime novel stories” (Nevins 2005: 821). Inspired by sensational newspaper accounts of a demonic assailant, John Thomas Haines brought the character to stage in 1840, followed by Alfred Coates’s 1866 penny dreadful. Alfred S. Burrage reimagined the character for two serials, the first also in 1886. John Springhall lists Spring-Heeled Jack among several highly popular penny dreadful characters (1994: 571), part of what Sheila Egoff identifies as a “brand of fantasy” that grew because boys “had little else to read in the adventure line after they had read Robinson Crusoe” (1980: 414). “In format, illustration, content, and popularity,” writes Egoff, such serial stories in boys’ sensational magazines “were matched only by the rise and influence of the comic book in the mid-twentieth century” (413). Peter Coogan acknowledges the character as the first “to fulfill the core definitional elements of the superhero” (2006: 177), and Jess Nevins declares him “the source of the 20th century concept of the dual identity costumed hero” (2005: 822).

It is striking then how deeply Spring-Heeled Jack is immersed in colonial narratives. In Alfred Burrage’s first treatment, Jack’s father is “a younger son” who “as was frequently the case in those days … had been sent out to India to see what he could do for himself” (1885: unpaginated). “[F]ortunes could be made in India by any who had fair connection, plenty of pluck, and plenty of industry,” and so Jack’s father “managed to shake the ‘pagado tree’ to a pretty fair extent,” resulting in his ownership of “plantation after plantation in the Presidencies.” After his death, the family’s lawyer plots with Jack’s cousin to cheat Jack of his inheritance, including “the Indian plantations.” The outlying colonial possessions both initiate the plot and provide its fantastical solution. Jack explains:

“I had for a tutor an old Moonshee, who had formerly been connected with a troop of conjurers … this Moonshee taught me the mechanism of a boot which … enabled him to spring fifteen or twenty feet in the air, and from thirty to forty feet in a horizontal direction.”

With the aid of this “magical boot” which “savoured strongly of sorcery,” Jack robs his enemies until his inheritance is restored. The old Moonshee (or munshi, an Urdu term for a writer which became synonymous with clerks and secretaries during British rule) is the first incarnation of Wonderman’s turbaned Tibetan, both variants of the magical mentor type transposed to a colonial setting. In both cases, a Westerner takes an Asian’s fantastical object to gain power at the metropolitan center of the empire, or metropole. Although narratively a hero, “Jack, who had been brought up under the shadow of the East India Company, had not many scruples as to the course of life he had resolved to adopt. To him pillage and robbery seemed to be the right of the well-born.”

As one of the first dual-identity heroes, Jack also imports a secondary persona that is not only contrastingly alien to his primary self but magical and demonic. As Richard Reynolds observes of the comic’s superhero character type: “His costume marks him out as a proponent of change and exoticism,” but because of his split self he “is both the exotic and the agent of order which brings the exotic to book” (1992: 83). Robert Young similarly notes how many nineteenth-century novels “are concerned with meeting and incorporating the culture of the other” and so “often fantasize crossing into it, though rarely so completely as when Dr Jekyll transforms himself into Mr Hyde” (1995: 3). So complete a binary transformation, while rare in other genres, is one of the defining tropes of the comic’s superhero, where a Jekyll-controlled Hyde defines what Marc Singer identifies as “the generic ideology of the superhero” in which “exotic outsiders …work to preserve” the status quo (2002: 110).

Jack’s relationship to the racial Other expresses itself beyond his Indian-powered and devil-inspired disguise. Due to his colonial childhood, Jack is no longer simply European: “‘I am not yet sixteen, but, thanks to my Oriental birth, I look more like twenty.’” He has been altered by living away from his empire’s center. Jack has absorbed an element of the alien, a dramatization of how imperial culture is inevitably altered by the cultures it dominates. Looking at recent conventions in science fiction, Kerslake proposes that “extreme travel must render the traveler into a different form” as “a component of Othering” (2007: 17). If “the place of departure is the traveler’s cultural ‘centre,’” Kerslakes asks “how far a person must now proceed before he or she reaches the indefinable edge of a nebulous periphery” or, more simply, “At what point do we become Other?” (18). The figure of the superhero embodies this question.

Spring-Heeled Jack also established the trope of the non-European mentor of a European protagonist, one more widely popularized by Kipling’s 1901 Kim, a novel Said classifies with works of Conan Doyle and Haggard in “the genre of adventure-imperialism” (1993: 155). Kipling depicts “a guru from Tibet” who needs an English boy in order to achieve his life quest, and Kim in turn treats him “precisely as he would have investigated a new building or a strange festival in Lahore city. The lama was his trove, and he purposed to take possession” (Kipling 1998: 6, 13). While no superhero, Kim does, in Said’s analysis, possesses a “remarkable gift for disguise” and fulfills “a wish-fantasy of someone who would like to think that everything is possible, that one can go anywhere and be anything,” a “‘going native’” fantasy permissible only “on the rock-like foundations of European power” (1993: 158, 160, 161).

Spring-Heeled Jack emerged during England’s expansion as an imperial power and, after numerous Victorian publications, vanished during the British Empire’s transition from traditional colonies to self-governing but British-dominated settler nations. Australia gained dominion status in 1901, followed by Canada, Newfoundland, and New Zealand in 1907. Anxiety over this transition can be seen in Baroness Orczy’s 1905 The Scarlet Pimpernel—the most cited of early superhero texts—in which the plot-driving periphery contracts to France and the threat of a newly independent, democratic mob. Similarly, when Burrage reinvented Spring-Heeled Jack for his 1904 serial, he removed the character from his Indian origins and recast him in relationship to the Napoleonic wars. The post-Victorian serial was discontinued before it reached narrative closure (Nevins 2005: 824). Martin Green argues that “Britain after 1918 stopped enjoying adventure stories” because such narratives “become less relevant and attractive to a society which has ceased to expand and has begun to repent its former imperialism” (1984: 4). In contrast, the United States continued as “a world ruler,” making the adventure story “a peculiarly American form” (4–5). The British Empire and the British superhero halted together, but the narrative type and its colonialist underpinnings were adopted by American authors as the United States pursued its own imperial ambitions.

December 19, 2022

Will Biden Be Re-elected?

Obviously I don’t know, and neither does anyone else. But here’s one reason for Democratic optimism, and one reason for utter uncertainty.

First, a look at the polls (as compiled by FiveThirtyEight):

Biden has been in close vicinity of 42% approval since late August. Nothing has moved the needle, including the unexpectedly strong midterms for the Democrats. If he remains there, his chances of winning seem very low — unless Trump wins the GOP nomination. Let’s assume Trump doesn’t win and Biden faces someone else (my strong guess is DeSantis). The question is: given his low approval at the midpoint of his first term, what could improve it?

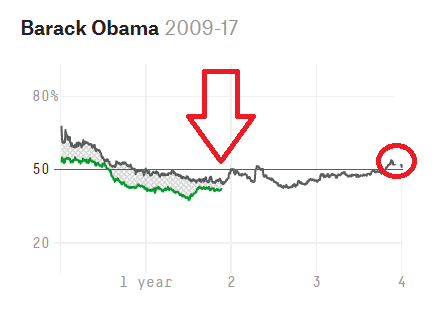

Historical precedents offer an answer. Look at Obama (thanks again, FiveThirtyEight):

The green line is Biden’s approval rating, the black Obama’s. Though Biden’s is lower, both were under 50% at their first midterm. But notice that Obama’s rose shortly afterwards in 2010, and, with some significant fluctuation, he was above 50% in time for re-election, which he of course won.

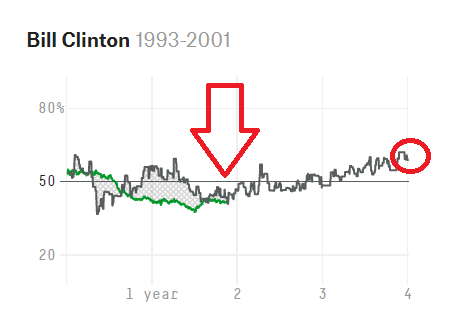

Now look at Clinton:

It’s a similar pattern. Clinton was below 50% at his first midterm, and then his approval rose in 1994, well above 50% come re-election.

What do Obama and Clinton have in common?

The Democrats lost control of the House at both midterms. Afterwards Clinton and Obama both looked better with a split government, especially with a dysfunctionally conservative House. In terms of re-election, having Newt Gingrich as Speaker was a gift for Clinton in 1996, and Obama had the entire Tea Party to thank in 2012.

And now Biden is about to have Kevin McCarthy for Speaker — assuming McCarthy can muster enough support from his right flank by January 3rd when the House votes. Pelosi had her in-party challenges too, both in 2021 and 2019, so I’m betting McCarthy pulls through. Still, the GOP’s unexpectedly small majority means hard-right Reps. like Gaetz and Greene and and Gosar and Boebert have major leverage. That’s what drove John Boehner out in 2015, and Paul Ryan out in 2019.

McCarthy is already struggling. The updates are daily and media-wide:

McCarthy’s ongoing speaker battle paralyzes HouseWhy Kevin McCarthy Is Struggling to Get Republicans in LineAllies of Kevin McCarthy Implore GOP Holdouts to Back Him for SpeakerKevin McCarthy’s speaker bid is rapidly accelerating toward chaosMcCarthy tries to boost his conservative bona fides as pro-Trump lawmakers threaten his speaker bidKevin McCarthy could face a floor fight for speaker. That hasn’t happened in a century.These Republicans refuse to support McCarthy for House speakerKevin McCarthy’s GOP extremism problem is a very bad omenMarjorie Taylor Greene will be the real Speaker behind the scenes even if Kevin McCarthy gets the jobPoll Shows Few Americans Believe House Republicans Will Enact Positive ChangeThat last one gives McCarthy a 12% approval rating. The composite polls at Real Clear Politics are kinder with a 22% average, but that is still significantly lower than Pelosi’s 35%.

So there’s reason to predict that Biden’s numbers will start to rise after McCarthy becomes Speaker of a newly GOP House on January 3rd (if GOP dysfunction prevents McCarthy from becoming Speaker then there’s even more reason).

But the Gingrich Effect isn’t the only factor, and it might not be the primary one.

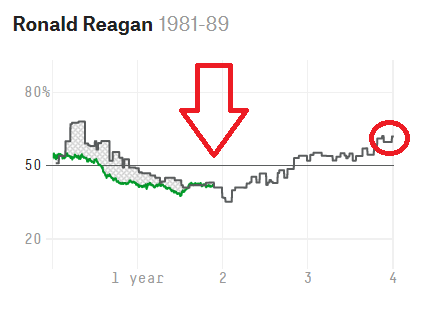

Take a look at Reagan:

His first-term trajectory follows the same pattern as Clinton’s and Obama’s — but for different reasons. The 1982 midterms didn’t usher in a new House majority. Democrats had controlled and continued to control the House, though with an increase of 27 seats. Setting aside the fact that the two parties still varied ideologically then (there were liberal, moderate, and conservative members in each), Reagan didn’t gain a new House Speaker as a public opponent. Tip O’Neill began as Speaker with Carter (1977) and left office with Reagan (1987).

Reagan’s post-midterm rise was linked to something else.

From 1980 to 1983, the world suffered the worst recession since World War II. Oil prices spiked. Triggered by the Iranian Revolution, a gallon of gas went from 63 cents in 1978 to $1.19 in 1980 (or $2.85 to $4.25 in 2022 dollars). Inflation hit 13.5% in 1980. After a “double-dip” recession from July 1981 to November 1982 (the month of the midterm election), Reagan’s approval dropped to a low of 35% in January 1983.

But as the U.S. economy began to recover from the “Reagan Recession,” so did his popularity. Inflation fell to 3.2% in 1983. Unemployment fell from a high of 10.8% in December 1982 to 7.2% on 1984 election day. Reagan’s reelection was tied to the economy.

What’s that say about Biden?

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor of Statistic, in May 2020 (during the pandemic lockdown), inflation dropped to .1%, and then it steadily rose to a 9.1% high in June 2022, before lowering to 7.1% in November.

Triggered by Russian invasion of Ukraine, gas went from $3.26 in 2021 to $4.90 in 2022 (Hallman).

Though U.S. economy is probably not currently in recession (as defined by two consecutive quarters of a generally slowing economy), some predictors are pointing in that direction.

Will inflation continue to drop? Will the price of gas? Will the next quarter show an economic increase?

I have no idea. But I do predict that Biden’s 2024 prospects will be a direct reflection of economic happenstance. 2023 will likely be rocky, but if Biden starts primary season with a solid economy, and given the Gingrich Effect from the House GOP, he should win a second term.

If not, his approval rating is likely to remain as flat as Trump’s:

Chris Gavaler's Blog

- Chris Gavaler's profile

- 3 followers