Marcia Thornton Jones's Blog, page 131

September 18, 2017

The Writing Lesson I Never Forgot: Write with Kindness

During my entire long career as a writer, I took only one creative writing course, during my junior year in high school. At the time I found it a somewhat painful experience because the teacher committed an unpardonable sin: he preferred my one-year-younger sister to me. Not that we were in the same class, or that he ever showed partiality in any overt or biased way. But I knew the two of them had a special closeness; he remains her favorite teacher, and I suspect she remains his favorite student, to this day. And, in that terrible way siblings can have of willfully claiming a part of the universe as their own, and shutting its doors against the other one, I was the writer, not her! I was the one he should have loved best.

But there's more. One of our assignments was to write a character sketch, and with the new-found cynicism of a sixteen-year-old, I wrote about our parents. I "saw through" them, documenting their disappointed dreams, timidity that blighted their lives, annoying eccentricities, even their middle-brow literary tastes (Readers Digest). I was proud of the piece, for how I had observed them so carefully and recorded my observations with such unflinching honesty. I expected that it would blow my teacher away. (Finally, he'd see how much better a writer I was than my sister).

He didn't like it.

He said it was impressively written in many ways, but that it wasn't kind.

The comment burned its way into my heart. I felt I had been judged negatively not only as a writer, but as a person. I actually gave up writing for a decade or so, focusing on the academic study of philosophy (many of the world's great philosophers weren't particularly kind).

But now I think that comment he gave me was so wise, so true, so totally right. It's not enough to see "through" our characters. We need to see "into" them. We need to understand not only how they are, but why they are this way. Clever observation needs to be deepened by compassionate understanding. Now I write about even my most flawed characters (who are usually my protagonists) with a kind of desperate love.

Decades later, when I read these words by Brenda Ueland in her wonderful 1938 manual, If You Want to Write, I finally realized exactly what Mr. Jaeger had been trying to tell me: "I have come to think that the only way to become a better writer is to become a better person."

Mr. Jaeger made me both.

But there's more. One of our assignments was to write a character sketch, and with the new-found cynicism of a sixteen-year-old, I wrote about our parents. I "saw through" them, documenting their disappointed dreams, timidity that blighted their lives, annoying eccentricities, even their middle-brow literary tastes (Readers Digest). I was proud of the piece, for how I had observed them so carefully and recorded my observations with such unflinching honesty. I expected that it would blow my teacher away. (Finally, he'd see how much better a writer I was than my sister).

He didn't like it.

He said it was impressively written in many ways, but that it wasn't kind.

The comment burned its way into my heart. I felt I had been judged negatively not only as a writer, but as a person. I actually gave up writing for a decade or so, focusing on the academic study of philosophy (many of the world's great philosophers weren't particularly kind).

But now I think that comment he gave me was so wise, so true, so totally right. It's not enough to see "through" our characters. We need to see "into" them. We need to understand not only how they are, but why they are this way. Clever observation needs to be deepened by compassionate understanding. Now I write about even my most flawed characters (who are usually my protagonists) with a kind of desperate love.

Decades later, when I read these words by Brenda Ueland in her wonderful 1938 manual, If You Want to Write, I finally realized exactly what Mr. Jaeger had been trying to tell me: "I have come to think that the only way to become a better writer is to become a better person."

Mr. Jaeger made me both.

Published on September 18, 2017 04:30

September 15, 2017

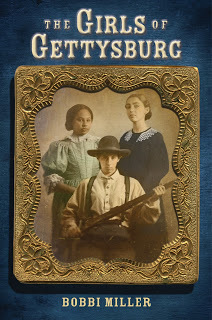

Introducing Bobbi Miller

I’m so excited to be joining the Smack Dab in the Middle! With a background in American folklore, I write historical fiction middle grade, focusing on forgotten characters (usually girls, who are not represented enough) and events (because I think as a nation, we are historically illiterate and have forgotten our own story) that helped build the American landscape. I like the challenge of writing historical fiction.

History is literature, David McCullough says. The artistic nature of historical fiction presents several challenges, especially in books for children. Events must be “winnowed and sifted”, as Sheila Egoff explains, in order to create forward movement that leads to a resolution. Authors choose between which details to include, and exclude, and this choice is wholly dependent upon the character’s goal. More important, resolution rarely happens in history. The same with happy endings. Because of the culling process, critics often claim that historical fiction is inherently biased.

Yet, nothing about history is obvious, and facts are often open to interpretation. In 1492, Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue, but he didn’t discover America. In fact (all puns intended), some would say he was less an explorer and more of a conqueror. History tends to be written by those who survived it. No history is without its bias. The meaning of history, just as it is for the novel, lays “not in the chain of events themselves, but on the historian’s [and writer’s] interpretation of it,” as Jill Paton Walsh once noted.

One hundred fifty one years ago, twelve thousand Confederate forces gathered along Seminary Ridge. Almost a mile away, at the end of an open field, a copse of trees marked the Union line standing firm on Cemetery Ridge. When the signal was given, the men marched across the field. The line had advanced less than two hundred yards when the federals sent shell after shell howling into their midst. Boom! Men fell legless, headless, armless, black with burns and red with blood. Still they marched on across that field.

As I was researching another book, I came across a small newspaper article dated from 1863. It told of a Union soldier on burial duty, following this Battle at Gettysburg, coming upon a shocking find: the body of a female Confederate soldier. It was shocking because she was disguised as a boy. At the time, everyone believed that girls were not strong enough to do any soldiering; they were too weak, too pure, too pious to be around roughhousing boys. It was against the law for girls to enlist. This girl carried no papers, so he could not identify her. She was buried in an unmarked grave. A Union general noted her presence at the bottom of his report, stating “one female (private) in rebel uniform.” The note became her epitaph. I decided I was going to write her story.

Some facts, such as dates of specific events, are fixed. We know, for example, that the Battle of Gettysburg occurred July 1 to July 3, in 1863. The interpretations of what happened over those three days remains a favorite in historical fiction. My interpretation of the battle, in Girls of Gettysburg (Holiday House, August 2014), featured three perspectives that are rare in these historical fiction depictions: the daughter of a free black living seven miles north from the Mason-Dixon line, the daughter of the well-to-do local merchant, and a girl disguised as a Confederate soldier. The plot weaves together the fates of these girls, a tapestry that reflects their humanity, heartache and heroism in a battle that ultimately defined a nation.

The literary process that defines historical fiction allows readers to connect emotionally to historical figures and events. It introduces readers to different points of view. As Tarry Lindquist (1995) said, historical fiction “puts people back into history.” While textbooks tend to underscore coverage, this lacks depth, and as a result, “individuals—no matter how famous or important—are reduced to a few sentences…Good historical fiction presents individuals as they are, neither good nor bad.”

Historical fiction helps young readers develop a feeling for a living past, illustrating the continuity of life, according to Karen Cushman. Historical fiction, “like all good history, demonstrates how history is made up of the decisions and actions of individuals and that the future will be made up of our decisions and actions.”

Historical fiction makes the facts matter to the reader. If I didn’t get the facts right, creating characters true to their time and place, the readers won’t care about the facts. For me, the only way to discover this emotional truth was to walk the battlefield of Gettysburg, and witness that landscape where my characters lived over one hundred and fifty years ago. Besides extensive reading, including scholarly pieces, diaries and journals , eyewitness accounts, military reports, I traveled to Gettysburg four times, walking the battlefield and talking to re-enactors and the park rangers.

History is story. And our history is full of amazing stories. That’s why I write historical fiction.

What's your favorite historical fiction?

Thank you for stopping by!

Bobbi Miller

Published on September 15, 2017 04:28

September 14, 2017

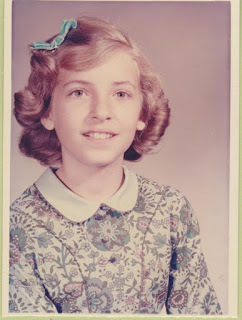

Introducing Michele Weber Hurwitz

I'm so excited to be joining Smack Dab in the Middle. I've enjoyed reading the blog for years and I'm thrilled to be a contributor now! I'll be posting on the 14th of each month.

I decided I wanted to be a writer when I was in fifth grade. That's about the time all big decisions are made, right? I wrote my first book that year -- The Chair That Knew How to Dance -- and it was one of the winners in a school contest. The prize? Reading my story to kindergartners. I still remember their excited five-year old faces as I turned each page, and it was right then and there that I realized this writing and reading thing was a pretty cool deal.

Oddly enough, my PE teacher at the time, Mr. Phillips, taught me an invaluable lesson about perseverance, and the experience stayed with me during years of writing rejections. Trampolines were still allowed in gym class back then and I was having a rough time mastering a flip. During one attempt, I knocked my knees into my face and got a bloody nose. Before Mr. Phillips let me go to the nurse, he insisted I try one more flip, telling me that if I didn't, I'd never get on the trampoline again. And that was the time I did it.

In college, I majored in journalism, then worked in public relations and wrote a newspaper column and magazine articles. The urge to write a book (not with crayon and construction paper) came when I was in book clubs with my two daughters. I fell in love with middle grade, perhaps even more so as an adult than as a preteen.

In college, I majored in journalism, then worked in public relations and wrote a newspaper column and magazine articles. The urge to write a book (not with crayon and construction paper) came when I was in book clubs with my two daughters. I fell in love with middle grade, perhaps even more so as an adult than as a preteen.

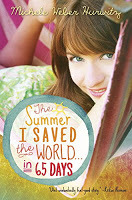

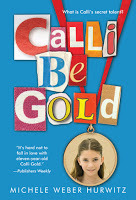

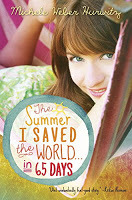

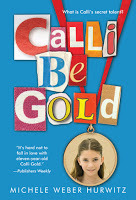

I'm the author of three middle grade novels (soon to be four). Calli Be Gold was published in 2011 by Random House/Wendy Lamb Books. It was nominated for state reading awards in Illinois and Minnesota, and named a starred Best Book by the Bank Street College of Education. The Summer I Saved the World in 65 Days, published by Penguin Random House/Wendy Lamb Books in 2014, was nominated for state reading awards in Florida, Nebraska, and Pennsylvania. It was a selection for several Girl Scout troop book clubs and has been a popular summer read in many school districts in conjunction with kindness and community service projects.

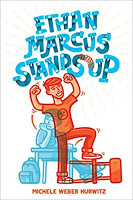

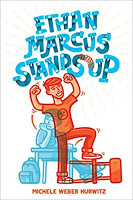

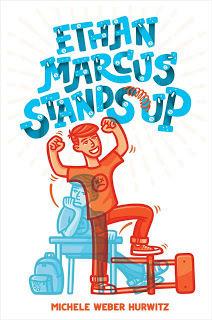

My newest release (this month!) is Ethan Marcus Stands Up. Narrated by five seventh-graders, it's the story of one fidgety kid who decides to take a stand against sitting by inventing his own solution to stop his constant squiggling in class. There's a sequel coming in fall 2018 -- Ethan Marcus Makes His Mark.

In addition to my two daughters, Rachel and Cassie, I have a son, Sam. They're all young adults now so I can't stalk them as much for ideas and dialogue like I did when they were younger :) I live in the Chicago area with my kids and husband, a CPA, which is helpful because math and numbers are my kryptonite. I walk every day -- it's essential to my writing process -- and I'm pretty fanatical about ice cream and chocolate chip cookies. And broccoli, when necessary. I'm an awful cook (except for banana bread) and have a terrible sense of direction (except in malls). I love to travel! This summer I went to Prague, Vienna, and Budapest. I can't wait to share my posts with you! Visit me at micheleweberhurwitz.com

Michele's books:

I decided I wanted to be a writer when I was in fifth grade. That's about the time all big decisions are made, right? I wrote my first book that year -- The Chair That Knew How to Dance -- and it was one of the winners in a school contest. The prize? Reading my story to kindergartners. I still remember their excited five-year old faces as I turned each page, and it was right then and there that I realized this writing and reading thing was a pretty cool deal.

Oddly enough, my PE teacher at the time, Mr. Phillips, taught me an invaluable lesson about perseverance, and the experience stayed with me during years of writing rejections. Trampolines were still allowed in gym class back then and I was having a rough time mastering a flip. During one attempt, I knocked my knees into my face and got a bloody nose. Before Mr. Phillips let me go to the nurse, he insisted I try one more flip, telling me that if I didn't, I'd never get on the trampoline again. And that was the time I did it.

In college, I majored in journalism, then worked in public relations and wrote a newspaper column and magazine articles. The urge to write a book (not with crayon and construction paper) came when I was in book clubs with my two daughters. I fell in love with middle grade, perhaps even more so as an adult than as a preteen.

In college, I majored in journalism, then worked in public relations and wrote a newspaper column and magazine articles. The urge to write a book (not with crayon and construction paper) came when I was in book clubs with my two daughters. I fell in love with middle grade, perhaps even more so as an adult than as a preteen.I'm the author of three middle grade novels (soon to be four). Calli Be Gold was published in 2011 by Random House/Wendy Lamb Books. It was nominated for state reading awards in Illinois and Minnesota, and named a starred Best Book by the Bank Street College of Education. The Summer I Saved the World in 65 Days, published by Penguin Random House/Wendy Lamb Books in 2014, was nominated for state reading awards in Florida, Nebraska, and Pennsylvania. It was a selection for several Girl Scout troop book clubs and has been a popular summer read in many school districts in conjunction with kindness and community service projects.

My newest release (this month!) is Ethan Marcus Stands Up. Narrated by five seventh-graders, it's the story of one fidgety kid who decides to take a stand against sitting by inventing his own solution to stop his constant squiggling in class. There's a sequel coming in fall 2018 -- Ethan Marcus Makes His Mark.

In addition to my two daughters, Rachel and Cassie, I have a son, Sam. They're all young adults now so I can't stalk them as much for ideas and dialogue like I did when they were younger :) I live in the Chicago area with my kids and husband, a CPA, which is helpful because math and numbers are my kryptonite. I walk every day -- it's essential to my writing process -- and I'm pretty fanatical about ice cream and chocolate chip cookies. And broccoli, when necessary. I'm an awful cook (except for banana bread) and have a terrible sense of direction (except in malls). I love to travel! This summer I went to Prague, Vienna, and Budapest. I can't wait to share my posts with you! Visit me at micheleweberhurwitz.com

Michele's books:

Published on September 14, 2017 03:00

September 13, 2017

Leaving Room For the Reader

Is, am, are, was, were, has, have, had, do, does, did, may, might, must, can, could, shall, will, should, would, be, being, been.

You will have to take my word for it that I wrote that list from memory. Those are the twenty-three helping verbs in the English language. They also represent the one and only thing my freshman high school English teacher, Mrs. Corbin, made us memorize that year.

I honestly don’t know why that was the sole memorization task she gave us, but my point here is really about everything else that happened while we weren’t learning prescribed information by rote. Instead, we spent a lot of time in that classroom figuring things out for ourselves, in what I’d call the best possible way.

Vocabulary lists started with small group work, where we’d come up with our own definitions before anyone cracked a dictionary. Creative writing assignments gave us free rein over our story ideas before Mrs. Corbin ever lowered the boom on mechanics and structure. There was an inherent trust in her teaching, an implicit message that we broughtsomething of value to the table, and that learning was a collaborative process.

It’s an idea I try to do justice to in my writing, as well. One of the tricky parts of creating middle grade fiction, for me, is in knowing how much information to give the reader, and how much they can (and should) figure out for themselves. Part of my job is to invite readers in as participants, not just observers. It’s up to me to trust them to fill in some of the gaps, using the power of their own imaginations.

The question is, what do I need on the page and what can I leave out? Which details are important enough to include? Which ones will readers willingly, even naturally, provide for themselves?

Beats me. It’s an art, not a science, and every reader is different. What might be implicit to one kid will feel like a frustrating lack of information to another. I’ll never get it 100% right because there’s no such thing. But I can work hard to ask myself the right questions as I'm drafting and revising. Do I need this detail? Have I already communicated it in some other way? Does it function as a story element, or is it merely decoration?

If some aspect of the setting or a character's physicality is germane (think Camp Green Lake in Holes; think Harry Potter’s scar), I’ll put it in. But if I’m unsure, my default is toward the “less is more” side of the fence.

Voltaire said the best way to be boring is to leave nothing out. Einstein said that everything should be made as simple as possible but no simpler. Those seem like a couple of good guideposts to me. Most of all, though, I go by my own taste, intuition, and gut feeling, with an eye on leaving the right amount of room inside the story for both of us—by which I mean the reader and me. It’s so much more fun that way.

I'd love to hear recommendations from any of you, in the comments section. What books do you think do this well? Which stories have that X factor that allows them to draw you (or readers you know) irresistibly inside? (I'll start: James and the Giant Peach; Out of the Dust; When You Reach Me.)

You will have to take my word for it that I wrote that list from memory. Those are the twenty-three helping verbs in the English language. They also represent the one and only thing my freshman high school English teacher, Mrs. Corbin, made us memorize that year.

I honestly don’t know why that was the sole memorization task she gave us, but my point here is really about everything else that happened while we weren’t learning prescribed information by rote. Instead, we spent a lot of time in that classroom figuring things out for ourselves, in what I’d call the best possible way.

Vocabulary lists started with small group work, where we’d come up with our own definitions before anyone cracked a dictionary. Creative writing assignments gave us free rein over our story ideas before Mrs. Corbin ever lowered the boom on mechanics and structure. There was an inherent trust in her teaching, an implicit message that we broughtsomething of value to the table, and that learning was a collaborative process.

It’s an idea I try to do justice to in my writing, as well. One of the tricky parts of creating middle grade fiction, for me, is in knowing how much information to give the reader, and how much they can (and should) figure out for themselves. Part of my job is to invite readers in as participants, not just observers. It’s up to me to trust them to fill in some of the gaps, using the power of their own imaginations.

The question is, what do I need on the page and what can I leave out? Which details are important enough to include? Which ones will readers willingly, even naturally, provide for themselves?

Beats me. It’s an art, not a science, and every reader is different. What might be implicit to one kid will feel like a frustrating lack of information to another. I’ll never get it 100% right because there’s no such thing. But I can work hard to ask myself the right questions as I'm drafting and revising. Do I need this detail? Have I already communicated it in some other way? Does it function as a story element, or is it merely decoration?

If some aspect of the setting or a character's physicality is germane (think Camp Green Lake in Holes; think Harry Potter’s scar), I’ll put it in. But if I’m unsure, my default is toward the “less is more” side of the fence.

Voltaire said the best way to be boring is to leave nothing out. Einstein said that everything should be made as simple as possible but no simpler. Those seem like a couple of good guideposts to me. Most of all, though, I go by my own taste, intuition, and gut feeling, with an eye on leaving the right amount of room inside the story for both of us—by which I mean the reader and me. It’s so much more fun that way.

I'd love to hear recommendations from any of you, in the comments section. What books do you think do this well? Which stories have that X factor that allows them to draw you (or readers you know) irresistibly inside? (I'll start: James and the Giant Peach; Out of the Dust; When You Reach Me.)

Published on September 13, 2017 07:00

September 12, 2017

It only Takes One Teacher: by Darlene Beck Jacobson

Mr. Costa, my fifth grade teacher, was a short, round man with glasses and a very serious disposition. He believed in hard work and LOTS of homework. We usually got something to do in every subject each night – except weekends. Mr. Costa was strict and took no nonsense. Still, we’d sometimes catch him falling asleep during a movie or silent reading. He was older than most of the other teachers. I think we “wore him out” on occasion.As strict and "old school" as Mr. C appeared, he was instrumental in leading me up a path that completely changed my life. Mr. C was the teacher who told mom during a conference that “Your daughter is college material. She’s smart and should plan on going to college. She’ll have a good future if she does.”I grew up in an area that was blue collar and low income. Not many people were college graduates and not many even attended college. So, having him say that made Mom feel great, and made me realize I might be able to do what he said. His confidence in my abilities and untapped potential gave me an early push toward a future I hadn’t thought about until then. I thought about it often after that. Never underestimate the influence one teacher can have on a student’s future.

Future college graduate and children's author. Thank you Mr. Costa!

Future college graduate and children's author. Thank you Mr. Costa!

Published on September 12, 2017 06:21

September 11, 2017

Writing Lessons My Teachers Never Taught Me

by Jody Feldman

Let me start with a confession:

Let me start with a confession: When I was in school, I never took a creative writing course voluntarily. Therefore, not learning these writing lessons was my fault entirely. I had awesome teachers. My peers were awesome creative writers. Additionally, my teachers may have mentioned some of these, but I was probably busy doodling snails and eyes in the margins of my spiral notebooks. Again, not their fault. The important point is, I did learn. And so I present one Top Nine List. Why nine? Look hard; you'll figure it out. Here goes.

Source material. You live it every day. Take notes about what moves you, amuses you, makes your ears perk up, stirs up some excitement in your gut. Even if it's a single word.Experiment. Sure, you have a series of events in mind and sure, you can envision your scenes. However, your first thoughts might not be the best ones for your book. No matter how much you believe in your characters' story, it's still fiction, a fabrication, totally made up. It's not sacred. Take every opportunity to experiment with pivotal scenes or points of view or secondary characters. Your best work may be limited by your misconception that what you've written is fact.Patience. I happen to have learned patience from my parents, or maybe I was hard-wired with a nice dose of it, but not as far as the publishing industry is concerned. Other authors and writers did warn me that the industry moves at glacial speed, but no one taught me what it feels like. Then again, that's pretty much unteachable.Table it. It's okay if you set a project aside. Case in point, 20 years ago I wrote a book that received amazing editorial comments; you know, the best rejections ever, including a couple R&Rs-revise and resubmit. I did and I did and I got the 3rd R, rejection. Turns out I didn't yet have the skills and the life experience to do justice to the concept and the characters. Now, the time is right. At least I think it is. We'll see. However…End it. Write a first draft through to the finish. If you bail midway through a story, don't expect to pick it back up and remember where you were going with it. There are no excuses here, not even shiny new ideas. Sorry. This discussion is over.Mine your writing. I can't tell you how many times I've run into a story situation that seems impossible to fix, no matter how much I employ lesson #2. And then, a miracle. I reread certain scenes and there, on page 87 during a fit of frenzied and unplanned writing, the essential idea or the emotion or the twist-or even the random object-is sitting right there. Not all the time, but enough to let me know that my subconscious is often smarter than I am. Blaze old trails. Depending on who you ask, there are only 7 (or 3 or 6 or 9 or 20) basic plots, so grab your favorite and go with it. However, a big HOWEVER. Knowing that, it's even more essential you populate your plots with rich and memorable characters and with fresh and unexpected details. That's what will set you apart.Editors are awesome, period. Reaching perfection. It's virtually unachievable. Every time you read your work, you'll find something to fix, even if it's as simple as transposing two phrases in a simple sentence. That's the bad news. The good news, it also means you are still learning. And all this can turn you into a teacher yourself.

Published on September 11, 2017 03:30

September 8, 2017

Teachers in Books -- by Jane Kelley

So many teachers have inspired me. Some I had when I was a girl; some taught my daughter; some invited me into their classrooms. But some of the most memorable teachers I know are characters in books.

Charlotte is a beautiful gray spider. When she first meets Wilbur, he is a dismayed that she sucks blood from insects. But she explains. “I live by my wits, lest I go hungry. I have to think things out, catch what I can, take what comes. And it just so happens that what comes is flies.”

As you know, in the story Charlotte saves Wilbur. But she accomplishes more than that clever trick of putting words on a web. She lifts him up from despair and loneliness. She doesn't just give him life; she gives him a reason to live.

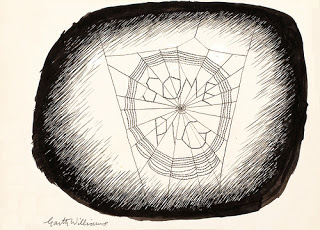

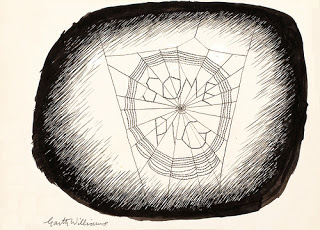

When he asks why she did that for him, she says: “You have been my friend. That in itself is a tremendous thing. I wove my webs for you because I liked you. After all, what’s a life anyway? We’re born, we live a little while, we die. A spider’s life can’t help being something of a mess, with all this trapping and eating flies. By helping you, perhaps I was trying to lift up my life a trifle. Heaven knows anyone’s life can stand a little of that.” Illustration by Garth Williams, copyright reserved Charlotte’s Web inspired me in so many ways. I loved it as a child, of course. Now that I write my own novels, I try to emulate its blend of realism and magic. But I also try to do what E.B. White did so well—make one of my characters a teacher.

Illustration by Garth Williams, copyright reserved Charlotte’s Web inspired me in so many ways. I loved it as a child, of course. Now that I write my own novels, I try to emulate its blend of realism and magic. But I also try to do what E.B. White did so well—make one of my characters a teacher.

In my first novel, Nature Girl, I had an old woman named Trail Blaze Betty guide Megan as she hiked part of the Appalachian Trail. Trail Blaze Betty gave Megan encouragement and helpful hints-- from a distance so that Megan could do the work herself.

In my current Work In Progress, I will make sure there is someone who can provide inspiration, information, and the opportunity for my hero to make her own way.

And if I do my job right, that teacher will do the same for me!

Charlotte is a beautiful gray spider. When she first meets Wilbur, he is a dismayed that she sucks blood from insects. But she explains. “I live by my wits, lest I go hungry. I have to think things out, catch what I can, take what comes. And it just so happens that what comes is flies.”

As you know, in the story Charlotte saves Wilbur. But she accomplishes more than that clever trick of putting words on a web. She lifts him up from despair and loneliness. She doesn't just give him life; she gives him a reason to live.

When he asks why she did that for him, she says: “You have been my friend. That in itself is a tremendous thing. I wove my webs for you because I liked you. After all, what’s a life anyway? We’re born, we live a little while, we die. A spider’s life can’t help being something of a mess, with all this trapping and eating flies. By helping you, perhaps I was trying to lift up my life a trifle. Heaven knows anyone’s life can stand a little of that.”

Illustration by Garth Williams, copyright reserved Charlotte’s Web inspired me in so many ways. I loved it as a child, of course. Now that I write my own novels, I try to emulate its blend of realism and magic. But I also try to do what E.B. White did so well—make one of my characters a teacher.

Illustration by Garth Williams, copyright reserved Charlotte’s Web inspired me in so many ways. I loved it as a child, of course. Now that I write my own novels, I try to emulate its blend of realism and magic. But I also try to do what E.B. White did so well—make one of my characters a teacher. In my first novel, Nature Girl, I had an old woman named Trail Blaze Betty guide Megan as she hiked part of the Appalachian Trail. Trail Blaze Betty gave Megan encouragement and helpful hints-- from a distance so that Megan could do the work herself.

In my current Work In Progress, I will make sure there is someone who can provide inspiration, information, and the opportunity for my hero to make her own way.

And if I do my job right, that teacher will do the same for me!

Published on September 08, 2017 03:00

September 7, 2017

INTERVIEW WITH MICHELE WEBER HURWITZ + GIVEAWAY OF ETHAN MARCUS STANDS UP

I (Holly Schindler, blog administrator) am absolutely delighted to talk again with Michele Weber Hurwitz (I'm a big fan of her MG THE SUMMER I SAVED THE WORLD IN 65 DAYS). I'm also delighted to announce that Michele will be joining us here at Smack Dab as a regular blogger!

Without further ado, my conversation with Michele:

Tell us about Ethan Marcus Stands Up.

Tell us about Ethan Marcus Stands Up.

Seventh-grader Ethan Marcus, who often gets scomas (school comas) in class and suffers from what his dad calls ESD (Ethan Squiggle Disease), literally takes a stand against the long hours of sitting in school. One afternoon in language arts, he leaps out of his chair and does a spontaneous protest. Although that lands him in “Reflection” – his school’s answer to detention – the kind-hearted, science-loving faculty advisor steers him toward the school’s Invention Day event as a way to channel his energy. Ethan’s not a science guy – that’s his perfectionist sister Erin’s department – but he’s motivated by his passion and determination to invent something to solve his constant fidgeting in class. He comes up with an idea and recruits his best friend to help (Brian Kowalski, who’s equally science-challenged). But Erin doubts he can pull it off. She and her friend Zoe are taking their invention much more seriously, and this heightens Ethan’s and Erin’s sibling rivalry and tension. Not to give away the ending, but in a roundabout way, Ethan and Erin come to understand and support each other.

What drew you to the maker movement?

It seemed that everywhere I turned, there was a maker event! The maker movement is so popular with kids and I thought it would be a fresher approach than a science fair. Plus, that allowed the characters to make anything, not only do science experiments.

I was also inspired by my son, who was always a high-energy kid and once told me his brain “works better” when he’s moving. I noticed how the workplace was incorporating standing desks and walking meetings, but the majority of schools – especially as kids got older – still had the same old desks and chairs. For a lot of kids, prolonged sitting just drains their energy. My son always studied while standing or moving around, usually bouncing a ball. So, I wanted to write about a character who tries to change the classroom environment, even if he needs to go outside of his comfort zone to do it.

I like the fact that you have a pretty even mix of boy and girl characters. Was that a challenge – writing a book that's not necessarily a "boy" or "girl" book? Do you even believe in the distinction?

There are three boy characters and two girls, and all of them narrate the story. This was the first time I wrote in a boy’s voice, and it was a definite challenge. Not so much that they’re boys, but the characters are so different than me. One character, Wesley, is a tough, closed-up kind of kid who’s having a rough time at home, and I had to work harder to get into his voice. I think that no matter a boy or girl character, it can be a challenge to inhabit the skin of a person who thinks so differently than you. I think (and hope!) this book will appeal to all kinds of readers. There’s certainly a lot in the story that rings true for middle graders, both boys and girls.

Describe the process of writing about siblings. Were your own kids an inspiration? Your own siblings? How so?

I have two younger brothers who are insanely competitive with each other and always have been. But for the book, I drew from my two older kids’ relationship. They have similar personalities to laid back, easy going Ethan and type A, always-on-top-of-things Erin. There are several scenes where Ethan and Erin totally get on each other’s nerves, and other times they try to understand, even empathize. I love the notion that we all see the world from different lenses but when we take a closer look, we realize we’re not so different. This happens to Ethan and Erin as the story unfolds. Even though they’re opposite personalities, they eventually see how it’s better to champion each other instead of get annoyed and argue.

For fans of your work: How is this book similar to your previous releases? How is it different?

One aspect that’s completely different is the style. It’s written in a conversational back and forth format, with each character sort of “commenting” on what’s going on and giving his or her version of the events. It was completely fun to write the story that way, like you’d see kids commenting on each other’s social media posts. There is also a lot of talking directly to the reader. That can be a tricky element but it worked for this story. My first two novels – Calli Be Gold and The Summer I Saved the World in 65 Days – both had one girl narrator. All of my books, however, are about underdog characters who are passionate about wanting to change something.

What's next?

What's next?

There’s a sequel to this book, coming in September 2018 – Ethan Marcus Makes His Mark. Ethan and Erin are nominated by the science teacher to attend a prestigious invention camp with brilliant kids from around their state. They aren’t sure if they’ll be able to measure up. But when they meet two new kids – Connor and Natalia – they dream up something that just might rise to the top. Not without some drama along the way, of course.And I’m working on another novel. It’s a return to my sweet spot – a sole 12-year old girl narrator. I adore writing in the voice of a 12-year old just on the verge of 13. It’s a pivotal time in life, that bridge between childhood and adulthood, where emotions are ripe, friendships change, and transitions abound.

~

Michele is giving away 1 signed hardcover of ETHAN MARCUS STANDS UP! Use the form below to enter; if you have trouble viewing it, you can enter by commenting below. a Rafflecopter giveaway

Without further ado, my conversation with Michele:

Tell us about Ethan Marcus Stands Up.

Tell us about Ethan Marcus Stands Up.Seventh-grader Ethan Marcus, who often gets scomas (school comas) in class and suffers from what his dad calls ESD (Ethan Squiggle Disease), literally takes a stand against the long hours of sitting in school. One afternoon in language arts, he leaps out of his chair and does a spontaneous protest. Although that lands him in “Reflection” – his school’s answer to detention – the kind-hearted, science-loving faculty advisor steers him toward the school’s Invention Day event as a way to channel his energy. Ethan’s not a science guy – that’s his perfectionist sister Erin’s department – but he’s motivated by his passion and determination to invent something to solve his constant fidgeting in class. He comes up with an idea and recruits his best friend to help (Brian Kowalski, who’s equally science-challenged). But Erin doubts he can pull it off. She and her friend Zoe are taking their invention much more seriously, and this heightens Ethan’s and Erin’s sibling rivalry and tension. Not to give away the ending, but in a roundabout way, Ethan and Erin come to understand and support each other.

What drew you to the maker movement?

It seemed that everywhere I turned, there was a maker event! The maker movement is so popular with kids and I thought it would be a fresher approach than a science fair. Plus, that allowed the characters to make anything, not only do science experiments.

I was also inspired by my son, who was always a high-energy kid and once told me his brain “works better” when he’s moving. I noticed how the workplace was incorporating standing desks and walking meetings, but the majority of schools – especially as kids got older – still had the same old desks and chairs. For a lot of kids, prolonged sitting just drains their energy. My son always studied while standing or moving around, usually bouncing a ball. So, I wanted to write about a character who tries to change the classroom environment, even if he needs to go outside of his comfort zone to do it.

I like the fact that you have a pretty even mix of boy and girl characters. Was that a challenge – writing a book that's not necessarily a "boy" or "girl" book? Do you even believe in the distinction?

There are three boy characters and two girls, and all of them narrate the story. This was the first time I wrote in a boy’s voice, and it was a definite challenge. Not so much that they’re boys, but the characters are so different than me. One character, Wesley, is a tough, closed-up kind of kid who’s having a rough time at home, and I had to work harder to get into his voice. I think that no matter a boy or girl character, it can be a challenge to inhabit the skin of a person who thinks so differently than you. I think (and hope!) this book will appeal to all kinds of readers. There’s certainly a lot in the story that rings true for middle graders, both boys and girls.

Describe the process of writing about siblings. Were your own kids an inspiration? Your own siblings? How so?

I have two younger brothers who are insanely competitive with each other and always have been. But for the book, I drew from my two older kids’ relationship. They have similar personalities to laid back, easy going Ethan and type A, always-on-top-of-things Erin. There are several scenes where Ethan and Erin totally get on each other’s nerves, and other times they try to understand, even empathize. I love the notion that we all see the world from different lenses but when we take a closer look, we realize we’re not so different. This happens to Ethan and Erin as the story unfolds. Even though they’re opposite personalities, they eventually see how it’s better to champion each other instead of get annoyed and argue.

For fans of your work: How is this book similar to your previous releases? How is it different?

One aspect that’s completely different is the style. It’s written in a conversational back and forth format, with each character sort of “commenting” on what’s going on and giving his or her version of the events. It was completely fun to write the story that way, like you’d see kids commenting on each other’s social media posts. There is also a lot of talking directly to the reader. That can be a tricky element but it worked for this story. My first two novels – Calli Be Gold and The Summer I Saved the World in 65 Days – both had one girl narrator. All of my books, however, are about underdog characters who are passionate about wanting to change something.

What's next?

What's next?There’s a sequel to this book, coming in September 2018 – Ethan Marcus Makes His Mark. Ethan and Erin are nominated by the science teacher to attend a prestigious invention camp with brilliant kids from around their state. They aren’t sure if they’ll be able to measure up. But when they meet two new kids – Connor and Natalia – they dream up something that just might rise to the top. Not without some drama along the way, of course.And I’m working on another novel. It’s a return to my sweet spot – a sole 12-year old girl narrator. I adore writing in the voice of a 12-year old just on the verge of 13. It’s a pivotal time in life, that bridge between childhood and adulthood, where emotions are ripe, friendships change, and transitions abound.

~

Michele is giving away 1 signed hardcover of ETHAN MARCUS STANDS UP! Use the form below to enter; if you have trouble viewing it, you can enter by commenting below. a Rafflecopter giveaway

Published on September 07, 2017 05:00

September 5, 2017

Middle Grade Book Clubs by Deborah Lytton

In my newest release, RUBY STARR (Sourcebooks Jabberwocky), the main character, Ruby loves reading so much that she starts her own book club at school. Book clubs can be a wonderful way to promote reading and positive social interactions. Ruby's book club was inspired in part by my daughter's fifth grade teacher who engaged her students in reading with in-class book clubs. She encouraged independent reading by allowing the students to choose from books she had pre-selected. There were adventure stories, classics, historical fiction, fantasies, and realistic fiction available. On the day of the book club, the fifth graders would separate into groups and participate in open discussion of themes in the reading by using a list of questions to get the conversations started. To make the atmosphere even more exciting, she would bring in snacks so that the students could eat strawberries and cookies while they talked about their books. I was privileged enough to work in the classroom that year, and I had the opportunity to sit with some of the groups. I was so impressed with the students' insights and opinions, and I found myself looking at the books differently because of the book clubs. Recently, I have noticed an increase in Middle Grade book clubs being offered at libraries. For students that love to read, those who struggle with reading or readers in between, participating in a book club can make a positive impression that just might last a lifetime.

Published on September 05, 2017 06:00

September 3, 2017

Dear Teachers, Reading Should Be Fun.

My father reading to his

My father reading to his firstborn son (the same way

he would later do with me,

but there aren't many

pics, because I am #3!)Dear Teachers,

Welcome to a new school year! You are AMAZING, did you know that? We authors/parents/citizens/humans appreciate everything you do.

And because reading is one of my most favorite activities -- and has been since my father held me in his lap and read Shel Silverstein poems to me -- I wanted to share some thoughts with you about reading.

1. Not every kid is going to love books, and that's okay. I wrote a post about this a few years ago over at Nerdy Book Club. One of my sons is dyslexic. The other two read on an as-needed basis. It's doesn't make me (or them) a failure. Fortunately we live in an age where there are a multitude of ways to enjoy stories!

wee me with a favorite book2. If you want the duckies to love reading, get them a classroom bathtub. That's what my third grade teacher Mrs. Fattig did. Her husband was a plumber, so she stationed a reading tub in the room, complete with pillows and plush toys... I remember we had to learn the fifty states, and we got to sit in the bathtub to recite them. I memorized them geographically, starting with Florida (where we lived), and working my way across the country. As it turns out, this method is NOT the most effective. The students who learned their states alphabetically consistently outperformed me! Since then I've visited other schools that feature reading bathtubs.

wee me with a favorite book2. If you want the duckies to love reading, get them a classroom bathtub. That's what my third grade teacher Mrs. Fattig did. Her husband was a plumber, so she stationed a reading tub in the room, complete with pillows and plush toys... I remember we had to learn the fifty states, and we got to sit in the bathtub to recite them. I memorized them geographically, starting with Florida (where we lived), and working my way across the country. As it turns out, this method is NOT the most effective. The students who learned their states alphabetically consistently outperformed me! Since then I've visited other schools that feature reading bathtubs.3. Kids are never too old to be read to. Want to create a culture of curiosity and wonder in your classroom? READ ALOUD. Want to create more empathetic humans? READ ALOUD. Want a world full of happy lifelong learners? READ ALOUD. And no, it doesn't matter how old they are. Just ask the book whisperer Donalyn Miller.

But you know all this already, don't you? Of course you do, because you're a reader and a lover of words and you are interested in authors and books and bookmaking and most of all, KIDS.

Not enough thank yous

Not enough thank yous for the parents,

friends and teachers

who've given me

BOOKS!THANK YOU.

Thank you for being the loving, encouraging teachers that you are.

You are making a difference.

You are making the world a better place.

I'm so grateful.

Sincerely,

Irene

----------------

Irene Latham is the author of more than a dozen current and forthcoming poetry, fiction and picture books for children and adults, including Leaving Gee's Bend, 2011 ALLA Children's Book of the Year. Winner of the 2016 ILA Lee Bennett Hopkins Promising Poet Award, she also serves as poetry editor for Birmingham Arts Journal.

Published on September 03, 2017 03:30