Marcia Thornton Jones's Blog, page 125

December 28, 2017

Creating Your Educator Resource Guide

Friday, December 29, 2017Creating Your Educator Research GuideBy Charlotte Bennardo

Photo courtesy of Pexels.com Now that you know you need (or should have) an educator research guide, it’s time to put together yours. The simplest guide is a series of questions, and this works particularly well for upper middle grade and young adult novels where literature teachers aren’t interested in craft projects and students don’t have words lists anymore. Keep in mind that questions for middle schoolers should be different than those posed to young adults. In Blonde OPS, one question is: Is it ethical for Beck to hack, deceive her boss and friends, and break and enter to find out who hurt Parker (a family friend)? This question asks students to think deeper into legal, ethical, and ‘the ends justifies the means’ scenarios. They can cite court cases, news events, etc. and in our tech world, look at their own behavior. For middle school children, using my

Evolution Revolution: Simple Lessons

as an example, a question in the guide asks, If you were Collin (boy) would you capture Jack (squirrel) for the college money? Posing this question to students makes them look at right vs wrong also, but on a simpler level- the temptation of turning in a beloved animal friend for money for college later on. Consider a wide range of questions for all learning abilities. I’ve included basic questions like: Are rats bad? Are there any animals that aren’t necessary? More advanced students can talk about diversity, the food chain, and every animal’s place in it. Others can relate how rats are pets and are very smart. Educators can also encourage students to think ahead- what do they think would happen next, if the story were to continue? What would happen to the characters? A mix of questions helps include students at multiple ability levels. Ten is a good number which should offer enough choices. As I mentioned previously, the best guides offer several pages of various resources. For the younger ones, a word list that students can look up and define helps broaden their vocabulary and introduce new concepts. For the more advanced students, a word list can incorporate complex concepts, like biodiversity. After providing a definition, students can be asked to supply an example. Another term, ‘flight or fight’ could be used to ask students to relate a time when they felt threatened, and maybe had to consider whether to fight or flee. Again, ten seems to be a magic number for offering choices. Next on your guide which is very popular to increase STEM and STEAM awareness, and could be used in conjunction with author visits, are home and classroom activities. Being that nature, ecology, habitat, and animal survival are central to the Evolution Revolution trilogy, I have, under each book, at least two activities that can be done in the home and/or classroom. One project is building a birdhouse. Students can work together or separately, and then the houses can be hung around the school for additional lessons on biology or taken home for student enjoyment. Search the web for simple projects to include (just make sure not to infringe on copyrights and/or give proper citation. I used www.craftionary.netbut scout around) or make up your own. Reinforcing the ideal of including all learning levels, have some simpler activities, like asking students to draw and color a scene from the book. In my guide, one activity is to play charades with some of the words on the word list so they will better understand how difficult it is to communicate without language, with an unknown language (‘squirrel’ vs human language). Not only fun, but educational! Finally, include other resources, like books or educational TV programs to reinforce or expand the lessons and teachings your book offers. I’ve listed books that focus on simple machines, as my trilogy is based on animals learning simple machines. One fun one is How Do You Lift a Lion? by Robert E. Wells (Albert Whitman). I do need to add a television resource citation from the BBC, which had the most amazing videos of squirrels outsmarting birdfeeders and puzzles. Lately, I’ve been thinking about adding more books about animals, to add some fun. (But that’s another post!) That’s my educator resource guide basics. Scan numerous author websites so that you can tailor your guide to fit your book. Ask teachers what they would like to see, what they want, what they have to have to fit curriculum requirements. You can pay someone to create a guide for you which will include reading levels and curriculum notes, etc. Consider cost and what you need (if you have several books it could get pricey). Start out basic- you can always update as you go along.

Photo courtesy of Pexels.com Now that you know you need (or should have) an educator research guide, it’s time to put together yours. The simplest guide is a series of questions, and this works particularly well for upper middle grade and young adult novels where literature teachers aren’t interested in craft projects and students don’t have words lists anymore. Keep in mind that questions for middle schoolers should be different than those posed to young adults. In Blonde OPS, one question is: Is it ethical for Beck to hack, deceive her boss and friends, and break and enter to find out who hurt Parker (a family friend)? This question asks students to think deeper into legal, ethical, and ‘the ends justifies the means’ scenarios. They can cite court cases, news events, etc. and in our tech world, look at their own behavior. For middle school children, using my

Evolution Revolution: Simple Lessons

as an example, a question in the guide asks, If you were Collin (boy) would you capture Jack (squirrel) for the college money? Posing this question to students makes them look at right vs wrong also, but on a simpler level- the temptation of turning in a beloved animal friend for money for college later on. Consider a wide range of questions for all learning abilities. I’ve included basic questions like: Are rats bad? Are there any animals that aren’t necessary? More advanced students can talk about diversity, the food chain, and every animal’s place in it. Others can relate how rats are pets and are very smart. Educators can also encourage students to think ahead- what do they think would happen next, if the story were to continue? What would happen to the characters? A mix of questions helps include students at multiple ability levels. Ten is a good number which should offer enough choices. As I mentioned previously, the best guides offer several pages of various resources. For the younger ones, a word list that students can look up and define helps broaden their vocabulary and introduce new concepts. For the more advanced students, a word list can incorporate complex concepts, like biodiversity. After providing a definition, students can be asked to supply an example. Another term, ‘flight or fight’ could be used to ask students to relate a time when they felt threatened, and maybe had to consider whether to fight or flee. Again, ten seems to be a magic number for offering choices. Next on your guide which is very popular to increase STEM and STEAM awareness, and could be used in conjunction with author visits, are home and classroom activities. Being that nature, ecology, habitat, and animal survival are central to the Evolution Revolution trilogy, I have, under each book, at least two activities that can be done in the home and/or classroom. One project is building a birdhouse. Students can work together or separately, and then the houses can be hung around the school for additional lessons on biology or taken home for student enjoyment. Search the web for simple projects to include (just make sure not to infringe on copyrights and/or give proper citation. I used www.craftionary.netbut scout around) or make up your own. Reinforcing the ideal of including all learning levels, have some simpler activities, like asking students to draw and color a scene from the book. In my guide, one activity is to play charades with some of the words on the word list so they will better understand how difficult it is to communicate without language, with an unknown language (‘squirrel’ vs human language). Not only fun, but educational! Finally, include other resources, like books or educational TV programs to reinforce or expand the lessons and teachings your book offers. I’ve listed books that focus on simple machines, as my trilogy is based on animals learning simple machines. One fun one is How Do You Lift a Lion? by Robert E. Wells (Albert Whitman). I do need to add a television resource citation from the BBC, which had the most amazing videos of squirrels outsmarting birdfeeders and puzzles. Lately, I’ve been thinking about adding more books about animals, to add some fun. (But that’s another post!) That’s my educator resource guide basics. Scan numerous author websites so that you can tailor your guide to fit your book. Ask teachers what they would like to see, what they want, what they have to have to fit curriculum requirements. You can pay someone to create a guide for you which will include reading levels and curriculum notes, etc. Consider cost and what you need (if you have several books it could get pricey). Start out basic- you can always update as you go along.Good luck! (And don’t forget to put the guide on your author website on its own page, boldly labeled Educator Resources so it can be easily found. Bring copies to author signings, book events, etc. to hand out to interested educators. If possible, send to teachers you know who might be interested or who know you. It might help you book a school visit or two!)

Published on December 28, 2017 21:16

December 27, 2017

Planning vs. Pantsing Endings

When it comes to writing, I’m a little bit of a planner and a bit more of a pantser. I’d call myself a plantser. There are some important things I need to know before I commit to writing a story: the opening, the main problem/stakes, the climax, and the ending. How it all flows together is something I’m willing to discover as I go along. One thing I'm absolutely not willing to leave to discovery or pantsing, though, is always the ending.

Have you ever read a story with a tremendous setup or an incredible idea only for it to fizzle out upon the big climax and ending? I think this is a case of the writer coming up with an amazing concept and then excitedly getting to work on it right away without figuring out how it should end. One of my favorite authors of all time is a terrible ender. He comes up with the most fantastic story ideas, sucking me in time and time again, only to leave me feeling dissatisfied with the ending. I still love him, but sometimes I wish he weren’t such a pantser.

I find myself constantly coming up with really cool ideas. For example: I would love to write a story about a small desert town that becomes enveloped in a dust storm. As time goes by, and the dust doesn’t clear, the people of the town begin to realize that there are dangerous things out in the dust. I have an interesting opening in mind and a great problem and stakes. But how do I end such a story? I don’t know. So that idea is perpetually on the backburner. Some people would be willing to risk writing it without knowing where it will end up, hoping it would all develop over time. And maybe it would. But maybe I’d write two hundred pages only to be stuck with a bad ending or no ending at all. I’m simply not a risk taker at heart. Writing is hard work, and I’d prefer not to waste my time.

For the next story I’m working on, I’m actually going to try my hand at creating a very detailed synopsis before I write it, which is something I’ve never done before. But the authors I know who decided to (or were forced to) make the change from pantser to planner mostly all say they’d never look back. It’s a lot easier to make changes to a synopsis than to a finished manuscript. Revisions to the later completed manuscript tend to be a lot simpler as a result. And, of course, you avoid the risk of ending your book in a dissatisfying way, which, in my opinion, is one of the worst things that can happen to a story.

Have you ever read a story with a tremendous setup or an incredible idea only for it to fizzle out upon the big climax and ending? I think this is a case of the writer coming up with an amazing concept and then excitedly getting to work on it right away without figuring out how it should end. One of my favorite authors of all time is a terrible ender. He comes up with the most fantastic story ideas, sucking me in time and time again, only to leave me feeling dissatisfied with the ending. I still love him, but sometimes I wish he weren’t such a pantser.

I find myself constantly coming up with really cool ideas. For example: I would love to write a story about a small desert town that becomes enveloped in a dust storm. As time goes by, and the dust doesn’t clear, the people of the town begin to realize that there are dangerous things out in the dust. I have an interesting opening in mind and a great problem and stakes. But how do I end such a story? I don’t know. So that idea is perpetually on the backburner. Some people would be willing to risk writing it without knowing where it will end up, hoping it would all develop over time. And maybe it would. But maybe I’d write two hundred pages only to be stuck with a bad ending or no ending at all. I’m simply not a risk taker at heart. Writing is hard work, and I’d prefer not to waste my time.

For the next story I’m working on, I’m actually going to try my hand at creating a very detailed synopsis before I write it, which is something I’ve never done before. But the authors I know who decided to (or were forced to) make the change from pantser to planner mostly all say they’d never look back. It’s a lot easier to make changes to a synopsis than to a finished manuscript. Revisions to the later completed manuscript tend to be a lot simpler as a result. And, of course, you avoid the risk of ending your book in a dissatisfying way, which, in my opinion, is one of the worst things that can happen to a story.

Published on December 27, 2017 22:00

Plotting vs. Pantsing Endings

When it comes to writing, I’m a little bit of a planner and a bit more of a pantser. I’d call myself a plantser. There are some important things I need to know before I commit to writing a story: the opening, the main problem/stakes, the climax, and the ending. How it all flows together is something I’m willing to discover as I go along. One thing I'm absolutely not willing to leave to discovery or pantsing, though, is always the ending.

Have you ever read a story with a tremendous setup or an incredible idea only for it to fizzle out upon the big climax and ending? I think this is a case of the writer coming up with an amazing concept and then excitedly getting to work on it right away without figuring out how it should end. One of my favorite authors of all time is a terrible ender. He comes up with the most fantastic story ideas, sucking me in time and time again, only to leave me feeling dissatisfied with the ending. I still love him, but sometimes I wish he weren’t such a pantser.

I find myself constantly coming up with really cool ideas. For example: I would love to write a story about a small desert town that becomes enveloped in a dust storm. As time goes by, and the dust doesn’t clear, the people of the town begin to realize that there are dangerous things out in the dust. I have an interesting opening in mind and a great problem and stakes. But how do I end such a story? I don’t know. So that idea is perpetually on the backburner. Some people would be willing to risk writing it without knowing where it will end up, hoping it would all develop over time. And maybe it would. But maybe I’d write two hundred pages only to be stuck with a bad ending or no ending at all. I’m simply not a risk taker at heart. Writing is hard work, and I’d prefer not to waste my time.

For the next story I’m working on, I’m actually going to try my hand at creating a very detailed synopsis before I write it, which is something I’ve never done before. But the authors I know who decided to (or were forced to) make the change from pantser to planner mostly all say they’d never look back. It’s a lot easier to make changes to a synopsis than to a finished manuscript. Revisions to the later completed manuscript tend to be a lot simpler as a result. And, of course, you avoid the risk of ending your book in a dissatisfying way, which, in my opinion, is one of the worst things that can happen to a story.

Have you ever read a story with a tremendous setup or an incredible idea only for it to fizzle out upon the big climax and ending? I think this is a case of the writer coming up with an amazing concept and then excitedly getting to work on it right away without figuring out how it should end. One of my favorite authors of all time is a terrible ender. He comes up with the most fantastic story ideas, sucking me in time and time again, only to leave me feeling dissatisfied with the ending. I still love him, but sometimes I wish he weren’t such a pantser.

I find myself constantly coming up with really cool ideas. For example: I would love to write a story about a small desert town that becomes enveloped in a dust storm. As time goes by, and the dust doesn’t clear, the people of the town begin to realize that there are dangerous things out in the dust. I have an interesting opening in mind and a great problem and stakes. But how do I end such a story? I don’t know. So that idea is perpetually on the backburner. Some people would be willing to risk writing it without knowing where it will end up, hoping it would all develop over time. And maybe it would. But maybe I’d write two hundred pages only to be stuck with a bad ending or no ending at all. I’m simply not a risk taker at heart. Writing is hard work, and I’d prefer not to waste my time.

For the next story I’m working on, I’m actually going to try my hand at creating a very detailed synopsis before I write it, which is something I’ve never done before. But the authors I know who decided to (or were forced to) make the change from pantser to planner mostly all say they’d never look back. It’s a lot easier to make changes to a synopsis than to a finished manuscript. Revisions to the later completed manuscript tend to be a lot simpler as a result. And, of course, you avoid the risk of ending your book in a dissatisfying way, which, in my opinion, is one of the worst things that can happen to a story.

Published on December 27, 2017 22:00

December 25, 2017

GREAT CRAFT READS (HOLLY SCHINDLER)

I love craft books. Talking serious, serious love. There are times I find myself reading more books on craft and plotting techniques than I read fiction. Here are a few books I've found especially helpful:

Or, if you're just taking the plunge on reading the-craft-of-writing books, a great place to start is always Save the Cat:

Or, if you're just taking the plunge on reading the-craft-of-writing books, a great place to start is always Save the Cat:

Published on December 25, 2017 05:00

December 22, 2017

Lighting the Bonfire of Your Imagination: by Dia Calhoun (Smack Dab in the Imagination)

We have survived the longest night of the year—again. Many people still light bonfires on Winter Solstice night. Bring greens in the house to encourage the sun to return. Light candles. Put lights on the evergreen trees. They’re waiting upon the darkness.

This is an act of the imagination. Imagination and the symbol generating capacity of the psyche are inextricably related in a way I’m still trying to understand. Someone postulated that it wasn’t an opposable thumb, and therefore tool-making ability, that led to human development, but our capacity to make symbols. I think that capacity emerged from our visual, pre-verbal experiencing of the world. I see a tree, though I have no word for it. It has fruit. Limbs I can climb to escape a predator. Without words, I see the tree and come to associate it with food and safety. This was the arising of symbolic thinking.

In the spirit of the bonfires burning to wait upon the dark last night, we can also set a fire to light our imaginations. I’ve been a writer since the second grade, but only in the last four years have my imaginative abilities truly taken flight. And I know why. I began to record and watch my dreams.

Dreams arise out of the dark, out of that pre-verbal symbol making place in our psyche. Dreams are pure metaphor. Gob-smackingly original. As I watched my dreams and saw over time how the symbols and metaphors developed, my ability to think metaphorically grew exponentially. It was set on fire. I was exercising the fundamental “muscle” where all writing arises from—all poetry, fairy tales, myth, and story.

I am perpetually awed at the abundance and richness going on way down deep. How much I had missed before I began paying attention. Dreams and myth are hard to understand—at first. The language of symbol and metaphor is really a foreign language to our conscious, rational minds. Like any foreign language, it has to be learned. If any artist, any person, takes the time to learn this language, to wait upon the long dark night, I promise that your imagination will blaze bonfire bright.

“If you wait upon the silence, it is not silent. And when you wait upon the darkness, it is luminous.” --CG Jung. Collected Works Volume 17

This is an act of the imagination. Imagination and the symbol generating capacity of the psyche are inextricably related in a way I’m still trying to understand. Someone postulated that it wasn’t an opposable thumb, and therefore tool-making ability, that led to human development, but our capacity to make symbols. I think that capacity emerged from our visual, pre-verbal experiencing of the world. I see a tree, though I have no word for it. It has fruit. Limbs I can climb to escape a predator. Without words, I see the tree and come to associate it with food and safety. This was the arising of symbolic thinking.

In the spirit of the bonfires burning to wait upon the dark last night, we can also set a fire to light our imaginations. I’ve been a writer since the second grade, but only in the last four years have my imaginative abilities truly taken flight. And I know why. I began to record and watch my dreams.

Dreams arise out of the dark, out of that pre-verbal symbol making place in our psyche. Dreams are pure metaphor. Gob-smackingly original. As I watched my dreams and saw over time how the symbols and metaphors developed, my ability to think metaphorically grew exponentially. It was set on fire. I was exercising the fundamental “muscle” where all writing arises from—all poetry, fairy tales, myth, and story.

I am perpetually awed at the abundance and richness going on way down deep. How much I had missed before I began paying attention. Dreams and myth are hard to understand—at first. The language of symbol and metaphor is really a foreign language to our conscious, rational minds. Like any foreign language, it has to be learned. If any artist, any person, takes the time to learn this language, to wait upon the long dark night, I promise that your imagination will blaze bonfire bright.

“If you wait upon the silence, it is not silent. And when you wait upon the darkness, it is luminous.” --CG Jung. Collected Works Volume 17

Published on December 22, 2017 22:00

December 20, 2017

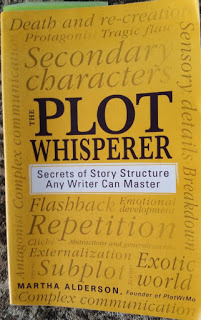

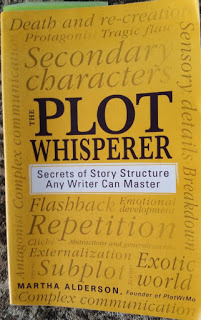

My Plot Secret? The Plot Whisperer by Martha Alderson

My journey to publication was a long one. I often wonder if it would have been shorter had I found Martha Alderson's The Plot Whisperer earlier in my endeavor to publish a book.

As a writer who is much more in tune to creating a character-driven story, my early manuscripts, though often well written, lacked a very important ingredient - PLOT. It might seem amazing to many readers and writers, that an entire book-length manuscript can be written without a tangible, concrete plot, but it's probably more common than most people imagine. For me, I knew my manuscripts were lacking "something," but I didn't necessarily think that my problem was plot. My writing group had begun a study of The Writer's Journey; and, though I had been writing for many years at this point, I remember being somewhat amazed by how little I really knew about the structure of story. As I studied The Writer's Journey/Hero's Journey by Christopher Vogler (talked about earlier this month on Smack Dab by Deborah Lytton), I slowly began to understand the idea of the universal story, but it wasn't until I read The Plot Whisperer that I finally understood how to really apply story structure to my own writing. Alderson breaks down the components that are necessary in all stories in order for them to really work. Her examples from literature help writers understand story structure and her scene tracker gives writers a tool to use in developing and revising their own plot. Besides her book, The Plot Whisperer, Alderson also has a DVD and workbook called Blockbuster Plots with even more helpful information and tools to help writers create and or strengthen the plot in their own writing.

I will be forever grateful for the way in which The Plot Whisperer gave me the necessary information and tools in order to turn a plot-less manuscript into a debut middle grade novel.

Happy Reading and Writing,Nancy

As a writer who is much more in tune to creating a character-driven story, my early manuscripts, though often well written, lacked a very important ingredient - PLOT. It might seem amazing to many readers and writers, that an entire book-length manuscript can be written without a tangible, concrete plot, but it's probably more common than most people imagine. For me, I knew my manuscripts were lacking "something," but I didn't necessarily think that my problem was plot. My writing group had begun a study of The Writer's Journey; and, though I had been writing for many years at this point, I remember being somewhat amazed by how little I really knew about the structure of story. As I studied The Writer's Journey/Hero's Journey by Christopher Vogler (talked about earlier this month on Smack Dab by Deborah Lytton), I slowly began to understand the idea of the universal story, but it wasn't until I read The Plot Whisperer that I finally understood how to really apply story structure to my own writing. Alderson breaks down the components that are necessary in all stories in order for them to really work. Her examples from literature help writers understand story structure and her scene tracker gives writers a tool to use in developing and revising their own plot. Besides her book, The Plot Whisperer, Alderson also has a DVD and workbook called Blockbuster Plots with even more helpful information and tools to help writers create and or strengthen the plot in their own writing.

I will be forever grateful for the way in which The Plot Whisperer gave me the necessary information and tools in order to turn a plot-less manuscript into a debut middle grade novel.

Happy Reading and Writing,Nancy

Published on December 20, 2017 04:30

December 19, 2017

On being “real”

The Christmas holidays remind me most of being a little girl. My sister and I waking up to full stockings that our mother had sewn little cats on, hanging on our retro electric fireplace.

My aunt always gifted us books. Oh, how I looked forward to Aunt Mary’s books! They were always new, with a special inscription from her. The pages were glossy or rough, and they smelled like the printing press. Shiny hardback covers or paperbacks as we got older.

Now that I have a niece, I am always sure to gift her a book at Christmas and at her birthday. A lifetime of collected books are a treasured thing to look back on. As I do this, this holiday season, I see my very life play out before me.

Here’s The Polar Express, when I still believed in Santa Claus. And Yes, Virginia There is a Santa Claus for the year that came when I didn’t. Practical Magic when I was a teenager and starting to read adult novels. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stonewhen my aunt thought I could use a trip back to childhood magic. And of course, The Velveteen Rabbit, when I had a pet bunny named Violet.

The Velveteen Rabbit is told by the Skin Horse that when you are truly loved, not just played with, you become real. Like the beloved Skin Horse, many of my childhood books are well past worn and broken in. With weak bindings and bent pages and scratches on the covers. It is in this way so many of these books have become real to me – part of my own life, or part of my way of thinking or beliefs. These books and so many others have become like trusted friends, ones I return to over and over for guidance or advice or simply the memories.

Happy holidays and happy reading!

A.M. Bostwick

My aunt always gifted us books. Oh, how I looked forward to Aunt Mary’s books! They were always new, with a special inscription from her. The pages were glossy or rough, and they smelled like the printing press. Shiny hardback covers or paperbacks as we got older.

Now that I have a niece, I am always sure to gift her a book at Christmas and at her birthday. A lifetime of collected books are a treasured thing to look back on. As I do this, this holiday season, I see my very life play out before me.

Here’s The Polar Express, when I still believed in Santa Claus. And Yes, Virginia There is a Santa Claus for the year that came when I didn’t. Practical Magic when I was a teenager and starting to read adult novels. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stonewhen my aunt thought I could use a trip back to childhood magic. And of course, The Velveteen Rabbit, when I had a pet bunny named Violet.

The Velveteen Rabbit is told by the Skin Horse that when you are truly loved, not just played with, you become real. Like the beloved Skin Horse, many of my childhood books are well past worn and broken in. With weak bindings and bent pages and scratches on the covers. It is in this way so many of these books have become real to me – part of my own life, or part of my way of thinking or beliefs. These books and so many others have become like trusted friends, ones I return to over and over for guidance or advice or simply the memories.

Happy holidays and happy reading!

A.M. Bostwick

Published on December 19, 2017 06:39

December 18, 2017

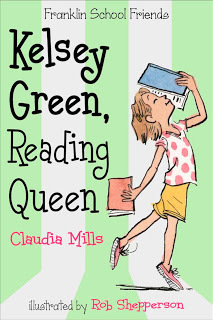

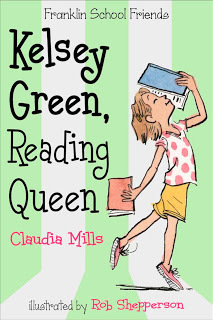

Finding the Plot Gifts You've Already Given Yourself by Claudia Mills

As far as plotting goes, I'm somewhere in between a plotter and a pantser. I have a general idea of where my story is heading, but I find all kinds of surprises that emerge for me in the course of the writing itself. So I've made it my practice, when I'm halfway through drafting a book, to give a careful review of what I've already scribbled, in order to locate the unexpected gifts that I've already given myself: elements of the story that lie there on the page, ready to be pressed into further service as I write toward the climax and resolution.

My rule for myself is that anything that happens in the first half of the book must earn its keep by making a repeat appearance, with heightened significance, in the second half of the book. This follows Chekhov's allged adage that if a gun is hanging over the fireplace in the first act of a play, it must go off in the final act.

So when I was writing Kelsey Green, Reading Queen, and feeling a bit stuck halfway through as to how I would bring the story to fruition, I re-read the first half and saw a whole bunch of gifts I had already given myself: I had opened the book with Kelsey surreptiously reading The Secret Garden during math time. Then I had a second scene of her furtive math-time reading. Surely I HAD to write a scene where Kelsey would get busted by her teacher, in a way that might compromise her pursuit of the school reading contest championship.

I had opened the book with Kelsey surreptiously reading The Secret Garden during math time. Then I had a second scene of her furtive math-time reading. Surely I HAD to write a scene where Kelsey would get busted by her teacher, in a way that might compromise her pursuit of the school reading contest championship.

Mr. Boone, the school principal, had told Kelsey's third-grade class that they had a good chance of beating out the fifth graders for the class title because the most amazing fifth-grade reader was going to be away on vacation for part of the contest time. Surely I HAD to bring that famous fifth-grade reader into the story at some point and give Kelsey a direct encounter with her,

Kelsey had expressed increasing annoyance at her parents' demands on her reading time, their requirement that she attend her sister's awards assembly and her brother's band concert, what her mother calls "being a family." Surely I HAD to have an explosive moment where Kelsey would let her irritation come to the boiling point: "I hate being part of this family!"

The list went on: gifts I had already given myself, gifts that I either needed to use to their fullest or return-to-sender.

O lucky author I was, that I had already, inadvertently, given myself so much promising material. BANG! went Chekhov's gun, as I fired my way happily to the book's finale.

My rule for myself is that anything that happens in the first half of the book must earn its keep by making a repeat appearance, with heightened significance, in the second half of the book. This follows Chekhov's allged adage that if a gun is hanging over the fireplace in the first act of a play, it must go off in the final act.

So when I was writing Kelsey Green, Reading Queen, and feeling a bit stuck halfway through as to how I would bring the story to fruition, I re-read the first half and saw a whole bunch of gifts I had already given myself:

I had opened the book with Kelsey surreptiously reading The Secret Garden during math time. Then I had a second scene of her furtive math-time reading. Surely I HAD to write a scene where Kelsey would get busted by her teacher, in a way that might compromise her pursuit of the school reading contest championship.

I had opened the book with Kelsey surreptiously reading The Secret Garden during math time. Then I had a second scene of her furtive math-time reading. Surely I HAD to write a scene where Kelsey would get busted by her teacher, in a way that might compromise her pursuit of the school reading contest championship.Mr. Boone, the school principal, had told Kelsey's third-grade class that they had a good chance of beating out the fifth graders for the class title because the most amazing fifth-grade reader was going to be away on vacation for part of the contest time. Surely I HAD to bring that famous fifth-grade reader into the story at some point and give Kelsey a direct encounter with her,

Kelsey had expressed increasing annoyance at her parents' demands on her reading time, their requirement that she attend her sister's awards assembly and her brother's band concert, what her mother calls "being a family." Surely I HAD to have an explosive moment where Kelsey would let her irritation come to the boiling point: "I hate being part of this family!"

The list went on: gifts I had already given myself, gifts that I either needed to use to their fullest or return-to-sender.

O lucky author I was, that I had already, inadvertently, given myself so much promising material. BANG! went Chekhov's gun, as I fired my way happily to the book's finale.

Published on December 18, 2017 09:16

December 17, 2017

Set Your Aim by Sarah Dooley

When I think of plot, the first thing that comes to mind isn't writing, or even reading. It's celeration charting. As a teacher in a Precision Teaching classroom, I rely on points plotted on a chart to give me information about the speed and accuracy with which my students are moving toward their aims.

As a bookworm kid, I never would have expected to grow up a math teacher - much less a math teacher who uses math to track her teaching - much less a math teacher who uses math to track her writing - but here we are. The celeration chart is beautiful because you can see at a glance how your learner is faring. Whether accuracy is maintained as the pace increases. Whether a skill is truly becoming fluent. You can get the whole picture at a glance.

This is a story about how math taught me to write synopses of unfinished plots.

There's a point, about forty percent or so into a novel, when I realize I am totally lost. It happens every time. Up to this point, I've been riding the adrenaline rush of new characters and setting, tasting the deliciousness of their language, dizzy on the unfamiliar atmosphere. But long about page one-oh-something, realization hits:

I have no idea what I'm doing.

My awesome new characters and beloved new setting aren't so new anymore, and they are bopping around their made-up universe, aimlessly waiting for me to make something happen.

This is the point when it's helpful for me to think of my novel like a snapshot -- a painting, a dust jacket description, a celeration chart. Whatever I need to envision to realize that if I take a few big steps back and look, I need to be able to see the whole picture, particularly where I'm headed. Only then can I set my aim, and with every plot point, move toward it.

An exercise that is helpful for me at the forty-to-sixty-percent point in my novel is this: I write the synopsis. Not the thorough, every-detail kind, but the kind you'd read on a dust jacket, a literary snapshot of the novel. Here's the book I'm writing. And yes, there will be things I've written that I'll have to cut because they don't fit on the page. And yes, I'll have to adjust my aim and plot a few points differently. But for me, stopping to summarize the novel my characters and I are mired in helps me ensure we're all accelerating in the same direction.

As a bookworm kid, I never would have expected to grow up a math teacher - much less a math teacher who uses math to track her teaching - much less a math teacher who uses math to track her writing - but here we are. The celeration chart is beautiful because you can see at a glance how your learner is faring. Whether accuracy is maintained as the pace increases. Whether a skill is truly becoming fluent. You can get the whole picture at a glance.

This is a story about how math taught me to write synopses of unfinished plots.

There's a point, about forty percent or so into a novel, when I realize I am totally lost. It happens every time. Up to this point, I've been riding the adrenaline rush of new characters and setting, tasting the deliciousness of their language, dizzy on the unfamiliar atmosphere. But long about page one-oh-something, realization hits:

I have no idea what I'm doing.

My awesome new characters and beloved new setting aren't so new anymore, and they are bopping around their made-up universe, aimlessly waiting for me to make something happen.

This is the point when it's helpful for me to think of my novel like a snapshot -- a painting, a dust jacket description, a celeration chart. Whatever I need to envision to realize that if I take a few big steps back and look, I need to be able to see the whole picture, particularly where I'm headed. Only then can I set my aim, and with every plot point, move toward it.

An exercise that is helpful for me at the forty-to-sixty-percent point in my novel is this: I write the synopsis. Not the thorough, every-detail kind, but the kind you'd read on a dust jacket, a literary snapshot of the novel. Here's the book I'm writing. And yes, there will be things I've written that I'll have to cut because they don't fit on the page. And yes, I'll have to adjust my aim and plot a few points differently. But for me, stopping to summarize the novel my characters and I are mired in helps me ensure we're all accelerating in the same direction.

Published on December 17, 2017 03:15

December 15, 2017

For Plot's Sake!

Who were your favorite characters when you were a young reader? Jo, of Little Women? Mattie, in True Grit? The Artful Dodger, in Oliver Twist? Emma, of Jane Austin fame? What about Huckleberry Finn? Why are we so drawn to certain characters?

If the plot is what happens to your character, then her motivation is the force that sets the plot into motion and keeps it going. It’s why she goes after her goal in the first place.

Fiction is primarily an emotional exchange. The reader stays connected to the hero because she feels the story. The reader wants to see the character succeed. She wants to see what happens next. The character’s motivation creates empathy between herself and the reader. After all, readers can empathize with a character’s motivation, especially if it’s similar to her own. Readers want to know why these characters are in the mess they are in. They what to know what happens to these characters.

An easy method to use in understanding your character’s motivation is simply to ask her. Just as you ask your friend or your significant other why s/he is doing something, ask your character. This is a freewrite exercise, no holds barred. Ask your character why does she yearn for this thing? What’s so important about it that she’s willing to take risks to get it? What is she willing to risk for it? How would she describe her current situation? If you hear inconsistencies in your character’s answers, don’t discard them, or ignore them! These inconsistencies make your character more human, and that means more authentic.

Just like when we don’t fully understand why we do the things we do, you’ll discover that your character does not always understand her behavior. This confusion, however, makes your character real to the reader. Her confusion reinforces her struggle.Her struggle is the heart of the plot. Madeleine L’Engle (The Heroic Personality, Origins of Story, 1999) offers that the heroic personality is human, not perfect. What it means to be human is “to be perfectly and thoroughly human, and that is what is meant by being perfect: human, not infallible or impeccable or faultless, but human.” Your character’s confusion is authentic. This sense of authenticity is important in keeping the reader connected to your story.

At the core of your character’s confusion is her inner struggle. This inner struggle is what your character brings to the plot. It’s there before the story begins. It’s the struggle that is holding her back in life. And she’ll carry this struggle throughout her story. James Scott Bell offers an experiment to help discover your character’s inner struggle: Write down the one positive character you want to the reader to understand most about your character. Is she determined, for example? Now, list those aspects that battle this characteristic, such as her timidity, or self-doubt. The presents the character’s inner struggle: she is fighting with herself to achieve her goals. Understanding how inner struggle influences motivation transforms your character “from plain vanilla to dynamic and dimensional.” (James Scott Bell, The Art of War For Writers, 2009)

And the key to understanding your character’s motivation is understanding your character’s history, called her backstory. Backstory is defined as simply what happened before the present story begins. Using backstory with care helps the reader to bond with your character. It deepens the relationship because it engages emotion and sympathy. Your character’s history relates to her inner struggle. As Dr Phil tells us, our past affects our present. Understanding this psychological make-up of your character adds depth to your story.

Of course, you won’t have to use everything you discover about your character. But, if you don’t know everything about your character, it shows in your writing!

Remember, the hero needs opposition to make her story worthwhile. Opposing characters simply stand contrary to your character. The antagonist may simply be all who disagree with the hero’s tactics. Villains, on the other hand, are usually dedicated to the destruction of the hero. Christopher Vogler describes the difference between antagonist and villains: “Antagonists and heroes in conflict are like horses in a team pulling in different directions, while villains and heroes in conflict are like trains on a head-on collision course.” (Writer’s Journey, 1992)

Like the hero, villains also need their motivation. Just as you sat down with your main character, spend some time talking to your villain. Why does she oppose your character? Why must she have this thing? What’s so important about it that she’s willing to take risks to get it? What is she willing to risk for it? How would your villain describe her current situation? How would she describe your lead character? How would she describe her relationship with the hero?

And, like the hero, your villain has a history. And this history influences her motivation. Her motivation moves the plot forward. Unless she was born evil, and few people are, villains were born human. Dean Koontz once offered that the best villains evoke pity, even sympathy, as well as terror. Sympathy for a villain, deepens a story. A bully doesn’t pick on someone just to be mean. Why did she become a bully? What would your villain say about her family? How was your villain raised? Did she experience a traumatic turning point that changed her emotionally?

In the end, villains are people, too.

Says Ralph Keyes (The Courage To Write, 1995), “Daring is always more riveting than skill. Any juggler knows that the real crowd pleaser isn’t his hardest task, such as keeping five balls in the air. The biggest oohs and ahhs are reserved for feats that look as though they could main him…Bold writers have the same relationship to readers that a juggler has to his crowd. When they seem to catch an errant machete by the blade, their readers stay glued to the page.”

So, for plot's sake, dare to go deeper into your character!

Wishing you amazing adventures for the holiday!

Bobbi Miller

Published on December 15, 2017 05:14