Marcia Thornton Jones's Blog, page 108

November 22, 2018

Gratitude for Imagination -- Smack Dab in the Imagination by Dia Calhoun

This Thanksgiving weekend I give thanks for a Rilke sonnet. It's one of the best expressions of the artist's imagination I have ever read and inspired one of my own sculptures...Daphne Becomes Laureate, pictured here. The poem, the 12th Poem in the Second Series of Sonnets to Orpheus, is about the Greek myth of Daphne's pursuit by Apollo (crowned with laurel, the poet's god) and her transformation into her essential nature--tree.

Strive for transformation, O be inspired with the flame

Wherein, rich in changes, a thing withdraws from your reach;

The planning spirit who masters everything earthly,

Loves above all in the sweep of the figure the point where it turns.

What locks itself in endurance grows rigid; sheltered

in unassuming grayness, does it feel safe?

Wait, from the distance hardness is menaced by something still

harder.

Alas—: a remote hammer is poised to strike.

Knowledge knows him who pours forth as a spring;

Delighted she guides him, showing him what was created in joy

And often concludes with the beginning and starts with the end.

Every happy space they traverse in wonder

Is child or grandchild of parting. And Daphne, transformed,

feeling herself laurel, wants you to change into wind.

This is an unpublished translation in Art and the Creative Unconscious by Erich Neumann page 205. This Thanksgiving, may you all find gratitude for your own imaginations.

Dia Calhoun is an author and sculptor. For more about her sculpture work, click here.

Published on November 22, 2018 22:00

November 20, 2018

Learning from the Best: Inspiration & Craft

One of my all-time favorite books is The Tiger Rising by Kate DiCamillo. What I love about this book is the simplicity of the story, the almost lyrical-like language, and the heart and soul of each one of the characters. These are the kinds of things that inspire me to write. So, when I create my characters and develop my plots, I think about the literary excellence of books like The Tiger Rising. And, it's my hope, that because of these amazing examples of storytelling, I am able to write a better middle grade book.

Besides inspiration, the nuts and bolts of my writing have been immensely improved by Martha Alderson's The Plot Whisperer. Alderson's clear, concise way of teaching authors about story structure has given me an understanding of how to put the parts of a story together in order to make it strong enough to one day be a book.

I will be forever grateful to Alderson for all that I have learned from her about writing, and I will always be thankful to all the authors like Kate DiCamillo who have inspired me to want to create books for middle grade readers.

Happy Reading!Nancy

Besides inspiration, the nuts and bolts of my writing have been immensely improved by Martha Alderson's The Plot Whisperer. Alderson's clear, concise way of teaching authors about story structure has given me an understanding of how to put the parts of a story together in order to make it strong enough to one day be a book.

I will be forever grateful to Alderson for all that I have learned from her about writing, and I will always be thankful to all the authors like Kate DiCamillo who have inspired me to want to create books for middle grade readers.

Happy Reading!Nancy

Published on November 20, 2018 04:30

November 19, 2018

Veteran writers I have learned from

I have, throughout my life, had many long-standing writers I have followed and learned from. In elementary school, I sought books by Roald Dahl, Judy Blume, Lucy Maud Montgomery and Farley Mowat. I also enjoyed anything from Gary Paulson and James Howe. When I reached junior high, I fell in love with the writing of Alice Hoffman, S.E. Hinton and Christopher Pike. These have all been authors I have continued to follow, and love, and learn from as I became a college student and adult. In more recent years, as I began writing middle grade and young adult, I’ve come to follow authors such as Sarah Dessen, J.K. Rowling, Maggie Stiefvater, Ruta Sepetys, Raymond Chandler and Tawni O’Dell. There’s also a smattering of local authors I follow, and of course my writing and critique partners who encourage and inspire me year after year. I discover new writers and authors every year, my stack of to-reads is sort of the never-ending gobstopper that Dahl cleverly wrote about in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. I wouldn’t want it any other way. Through following our favorite authors, we see their writing styles hold steady with the familiar prose we love, and we often see them grow and change and enhance in both plot, character, world-building and construction of sentences. By always searching for new authors and writers, we keep our minds open and see different ways a novel can work. Or perhaps not work – not every style will fit every writer, and that’s okay. I hope my writing reflects the same, that I never stop learning and expanding as a writer. That my words get better and better as life goes on. Happy Reading!

Published on November 19, 2018 06:00

November 18, 2018

Inspiration from a Literary Idol

My favorite book as a child, dreaming of someday becoming a writer, was Betsy and Tacy Go Downtown by Maud Hart Lovelace.

My favorite book half a century later, as a children's book writer with dozens of books to my credit, is Betsy and Tacy Go Downtown by Maud Hart Lovelace.

My favorite book half a century later, as a children's book writer with dozens of books to my credit, is Betsy and Tacy Go Downtown by Maud Hart Lovelace.

Throughout the entire Betsy-Tacy series, which begins with Betsy-Tacy (1940), where Betsy first meets Tacy at her fifth birthday party, and culminates in Betsy's Wedding (1955), we see Betsy making up stories for her best friends Tacy and Tib, scribbling stories on promotional pads from her father's bookstore, receiving her first rejection for a story, having her first publication for a poem, competing in her high school essay contest, and finally marrying a fellow writer and creating a home together where both of them can flourish as authors.

These might be the best books ever written in the history of the world!

My fervent fandom for the books has led to so many touchstones in my career as a writer.

Because the books are heavily autobiographical, I was able to visit Mankato, Minnesota, the "Deep Valley" of the series, and make a pilgrimage to Betsy's house and Tacy's house, now maintained as charming museums by the Betsy-Tacy Society, of which of course I'm a lifetime member. The crowning moment of my career - and life! - was when I did a book signing at Tacy's house more than a decade ago.

I've published half a dozen scholarly articles on the Betsy-Tacy books in academic children's literature journals, and in 2017 I received a grant to do research at the Kerlan Collection at the University of Minnesota, where Lovelace's papers are archived.

There I was able to witness first hand the meticulous research Lovelace did for each book, not relying on her own memories, but poring over back issues of Ladies Home Journal to note titles of magazine articles, products featured in advertisements, changing fashions, mentions of popular songs and dances, recipes, and more. She also engaged in voluminous correspondence with childhood friends fictionalized in the books, pumping them with questions like, "What were your religious beliefs about the time you were a sophomore in college? Did college work any change in them?" - favorite music ("Name pieces"), family traditions, personalities of their siblings, and further details about favorite stories, like "the time you took your grandmothers to the circus."

My favorite line in one of these letters, to Marion Willard (the original for Carney in Carney's House Party), was this one: "I can assure you that . . . as in the previous Betsy Tacy books . . . all the characters with any resemblance to living persons, living or dead, will be handled with loving kindness."

That has become a touchstone for me in my own writing: to handle all my characters (even though mine are almost entirely fictional) with the loving kindness that radiates through every Betsy-Tacy book.

At a silent auction at one of the Betsy-Tacy fandom conventions I attended, I even had the chance to purchase - yes !! - half a dozen ACTUAL PAPERCLIPS "used by Maud Hart Lovelace for her Betsy-Tacy manuscripts and research notes."

I've never yet opened this little packet or dared to place one of Maud's paperclips on my own manuscripts or research notes. I don't think I've ever yet felt worthy. Maybe I'll try to be brave enough to use just ONE of her paperclips in the coming year, hoping it will imbue what I write with her magic, with her wise and compassionate loving kindness. Maybe it will inspire me to try even harder to be for some other young reader the great gift she was, and will always be, for me.

I've never yet opened this little packet or dared to place one of Maud's paperclips on my own manuscripts or research notes. I don't think I've ever yet felt worthy. Maybe I'll try to be brave enough to use just ONE of her paperclips in the coming year, hoping it will imbue what I write with her magic, with her wise and compassionate loving kindness. Maybe it will inspire me to try even harder to be for some other young reader the great gift she was, and will always be, for me.

My favorite book half a century later, as a children's book writer with dozens of books to my credit, is Betsy and Tacy Go Downtown by Maud Hart Lovelace.

My favorite book half a century later, as a children's book writer with dozens of books to my credit, is Betsy and Tacy Go Downtown by Maud Hart Lovelace.Throughout the entire Betsy-Tacy series, which begins with Betsy-Tacy (1940), where Betsy first meets Tacy at her fifth birthday party, and culminates in Betsy's Wedding (1955), we see Betsy making up stories for her best friends Tacy and Tib, scribbling stories on promotional pads from her father's bookstore, receiving her first rejection for a story, having her first publication for a poem, competing in her high school essay contest, and finally marrying a fellow writer and creating a home together where both of them can flourish as authors.

These might be the best books ever written in the history of the world!

My fervent fandom for the books has led to so many touchstones in my career as a writer.

Because the books are heavily autobiographical, I was able to visit Mankato, Minnesota, the "Deep Valley" of the series, and make a pilgrimage to Betsy's house and Tacy's house, now maintained as charming museums by the Betsy-Tacy Society, of which of course I'm a lifetime member. The crowning moment of my career - and life! - was when I did a book signing at Tacy's house more than a decade ago.

I've published half a dozen scholarly articles on the Betsy-Tacy books in academic children's literature journals, and in 2017 I received a grant to do research at the Kerlan Collection at the University of Minnesota, where Lovelace's papers are archived.

There I was able to witness first hand the meticulous research Lovelace did for each book, not relying on her own memories, but poring over back issues of Ladies Home Journal to note titles of magazine articles, products featured in advertisements, changing fashions, mentions of popular songs and dances, recipes, and more. She also engaged in voluminous correspondence with childhood friends fictionalized in the books, pumping them with questions like, "What were your religious beliefs about the time you were a sophomore in college? Did college work any change in them?" - favorite music ("Name pieces"), family traditions, personalities of their siblings, and further details about favorite stories, like "the time you took your grandmothers to the circus."

My favorite line in one of these letters, to Marion Willard (the original for Carney in Carney's House Party), was this one: "I can assure you that . . . as in the previous Betsy Tacy books . . . all the characters with any resemblance to living persons, living or dead, will be handled with loving kindness."

That has become a touchstone for me in my own writing: to handle all my characters (even though mine are almost entirely fictional) with the loving kindness that radiates through every Betsy-Tacy book.

At a silent auction at one of the Betsy-Tacy fandom conventions I attended, I even had the chance to purchase - yes !! - half a dozen ACTUAL PAPERCLIPS "used by Maud Hart Lovelace for her Betsy-Tacy manuscripts and research notes."

I've never yet opened this little packet or dared to place one of Maud's paperclips on my own manuscripts or research notes. I don't think I've ever yet felt worthy. Maybe I'll try to be brave enough to use just ONE of her paperclips in the coming year, hoping it will imbue what I write with her magic, with her wise and compassionate loving kindness. Maybe it will inspire me to try even harder to be for some other young reader the great gift she was, and will always be, for me.

I've never yet opened this little packet or dared to place one of Maud's paperclips on my own manuscripts or research notes. I don't think I've ever yet felt worthy. Maybe I'll try to be brave enough to use just ONE of her paperclips in the coming year, hoping it will imbue what I write with her magic, with her wise and compassionate loving kindness. Maybe it will inspire me to try even harder to be for some other young reader the great gift she was, and will always be, for me.

Published on November 18, 2018 06:18

November 15, 2018

Learning to Dance with the Dingoes!

I recently wrote about my ongoing search for a new agent. Despite having six books published, including a graphic novel that's coming out next year, it’s a challenging task because I write historical fiction. I focus on forgotten characters (usually girls, who are not represented enough) and events (because I think as a nation, we are historically illiterate and have forgotten our own story) that helped build the American landscape. I also write American fantasy, both contemporary and historical, blending the tall tale tradition of humor and exaggeration that captures so much of the American identity into a unique form of fantasy. I touched upon the challenges of historical fiction, the ongoing argument on what is historical fiction, how and why it is relevant, and by extension why history is important. As a writer, one of the most stinging rejections that I get too many times is that, despite an interesting plot and engaging characters, “historical fiction is a hard sell.” (See my article Historical Fiction and All That Wibbly Wobbly Timey Wimey Stuff.)

And yet, historical fiction seems to be one of those steadfast genres. As UK literary agent Kate Burke (What’s Hot in Historical Fiction, 2018), a common theme in popular historical fiction over the last thirty years is that protagonists in historical fiction tend to be “suffering witness to history”, in which writers pair small characters with big circumstances.This pairing seems perfect for middle grade and young adult readers. To illustrate this point, consider Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief (2005), in which foster child Liesel struggles to survive the rise of Nazism, Germany. Or Kimberly Brubaker Bakdley’s The War That Saved My Life (2015), which follows ten-year old Ada’s plight to survive in war torn London. Or Laurie Halse Anderson’s Chains (2008), in which the cruelty of slavery is seen through the POV of thirteen year old Isabel. In fact, Arleigh Ordoyne of the Historical Novel Society (Young Adult War Fiction: Fixture or Trend, 2018) suggests that roughly half of the historical fiction published in recent years can be categorized as war fiction. And while more are sandwiched in eras between wars, these characters tend to be immersed in war-affected circumstances. Historical fiction consistently wins the Newbery Award. Consider Clare Vanderpool’s Moon Over Manifest (2011), Laura Amy Schlitz’s Good Masters! Sweet Ladies! Voices from a Medieval Village (2008), Lynne Rae Perkin’s Criss Cross (2006), Cynthia Kadohata’s Kira Kira (2005).

"But history isn’t really about the past. It’s about human nature. We use the genre as a lens to see ourselves in a different age. To write on the human condition is to write with a reliance on history." -- Justin O’Donnell, Why Historical Fiction Will Never Go Away

So why the hard sell? And where do I fit in?

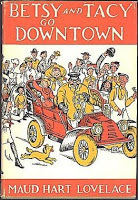

To answer these questions, and find the courage to keep going, I came across two inspirational reads that address the writer’s plight.

Michael Alvear, and his The Bulletproof Writer: How to Overcome Constant Rejection to Become an Unstoppable Author (2017). Alvear has published fifteen books, written columns for The Washington Post and New York Times, and contributes to NPR's All Things Considered. ALL authors, reaffirms Alvear, deal with constant rejection. And we’ve heard all the testimonies from famous writers like J.K. Rowling and Stephan King and Ursula LeGuinn. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich rejected J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. Publisher and editor Barney Rossett hated J.R.R.Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, calling it a mishmash.

In fact, as Alvear asserts, “publishing is one of the few industries that systematically rejects its most talented people.” Would Sony or Verizon reject Steve Job’s resume with a form letter? Would Citigroup tell Warren Buffet that he doesn’t have what they’re looking for? That he doesn’t fit in?

Rejection becomes like an infection, says Alvear. We internalize it, give it more meaning than it deserves, and amplify it by taking on a chronically self-critical inner voice. It makes us question our skills, and our worth. It gives us writer’s block, and worse. It can also make us give up altogether.

What I like about this book is that he doesn’t offer cutesy quotes or power slogans, or as he calls them, motivational Band-Aids. Instead, he gives insights into how and why we receive, interpret, and react to rejection, then he offers some tools that we can use to move past the rejection. And the first thing he does is to outline three basic facts about the publishing business:

Rejection is most likely not an indictment of your work. No matter how many books you’ve published, you will not be spared the wrath of rejection.Less than one percent of writers make a living wage. The odds are overwhelmingly against you.BUT! -- and this is a big but -- on the other side of rejection is acceptance.

Grounded in science, Alvear looks at how the brain is hardwired for fight or flight. Rejection feeds on the writer’s worse fears. And, according to Alvear, it can feel like it’s just a matter of time before the dingo eats your baby. “The brain is like Velcro for negative experiences, but Teflon for positive ones,” he quotes his research. The nature of publishing reinforces this built-in negative bias. The trick is, of course, is learning strategies that make the positive stick like Velcro.

In other words, we need to learn to dance with the dingoes!

Fearless Writing, by William Kenower (2017). This is the perfect companion to Alvear. Drawing on personal experience, Kenower elaborates on the writer’s worst fear: what other people think of our writing is more important than what we think of our writing. As Kenower suggests, what makes this fear so insidious is because of its apparent practicality, reinforced by the nature of the publishing business. As working writers, we need others to like our writing: agents, editors, publishers, critics and, most importantly, readers. Sometimes this fear becomes so overwhelming, we become blocked, or change the story we want to write to what we think others would read. Either way, we lose our story. Kenower offers a series of practical exercises that explores how to break the hold of this particular fear, and to find the confidence to write your story fearlessly. Don’t fear the wobble, Kenower states. Just write your story.

I just received my 36th rejection of the year. BUT I have also just finished another story, and have begun that process of submission. Yes, onward!

“Whenever I got those rejection letters, I would permit my ego to say aloud to whoever had signed it: ‘You think you can scare me off? I’ve got another 80 years to wear you down! There are people who haven’t even been born yet who are going to reject me some day – That’s how long I plan to stick around.’” – Elizabeth Gilbert, Eat, Pray, Love.

Bobbi Miller

Published on November 15, 2018 03:52

November 14, 2018

Middle Grade Then and Now, by Michele Weber Hurwitz

When I was young, there wasn't really a category of books that were designated as 'middle grade.' I remember reading and loving Scott O'Dell's Island of the Blue Dolphins. (Oh, to live on my own island, away from my annoying two younger brothers!) I read classics, like Heidi and Little Women. And later, in high school, I read S.E. Hinton's The Outsiders and a slew of books by Paul Zindel, the most memorable being My Darling, My Hamburger. He was more or less a YA author before that genre was called YA. I remember reading gothic romance novels too, like Green Darkness by Anya Seton, which were all the rage when I was 16.

It wasn't until I was a mom and participated in mother-daughter book clubs with my daughters that I read today's middle grade novels. And fell in love with them. There were two that resonated so much that I knew I wanted to write one of these books. Or try to, anyway. They were So B. It by Sarah Weeks and Love, Ruby Lavender by Deborah Wiles.

I didn't think these novels were just for 9-12 year olds! They're compelling, deep, heartfelt, poignant, real stories with true-to-life characters that get under your skin. Plots that prompt the reader to ponder important, essential life questions. Conflict that keeps the pages turning.

I didn't think these novels were just for 9-12 year olds! They're compelling, deep, heartfelt, poignant, real stories with true-to-life characters that get under your skin. Plots that prompt the reader to ponder important, essential life questions. Conflict that keeps the pages turning.

Could I create something like that?

I read them several times. I studied them. I learned what ingredients made up a good story for this age group.

I tried to write a middle grade novel. Fail (of course). I wrote another. Fail #2. Those documents are stored safely on my computer and they're not going anywhere. I think of them as practice books, sort of like an archeological remnant of early cave drawings. But, like those plucky heroines in the two books who are determined to pursue answers, I kept at it. And at some point, something worked. I wrote something that got a nibble. Then a deal!

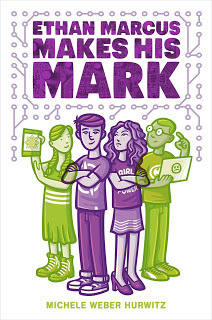

This month, my fourth middle grade novel will be released from Aladdin Books, Ethan Marcus Makes His Mark. It's a sequel to last year's Ethan Marcus Stands Up. I had such fun with these two books, which are narrated by five seventh-graders, digging into themes of determination, sibling rivalry, and learning to get along with others who see the world from a different lens.

I don't think I've quite yet reached the level of Deborah's and Sarah's extraordinary works, but I keep trying. I continue to be inspired by them and so many other middle grade authors.

There's no other writing world I'd rather be a part of.

Michele Weber Hurwitz is the author of Calli Be Gold, The Summer I Saved the World in 65 Days, Ethan Marcus Stands Up, and Ethan Marcus Makes His Mark. Catch up with her at micheleweberhurwitz.com.

It wasn't until I was a mom and participated in mother-daughter book clubs with my daughters that I read today's middle grade novels. And fell in love with them. There were two that resonated so much that I knew I wanted to write one of these books. Or try to, anyway. They were So B. It by Sarah Weeks and Love, Ruby Lavender by Deborah Wiles.

I didn't think these novels were just for 9-12 year olds! They're compelling, deep, heartfelt, poignant, real stories with true-to-life characters that get under your skin. Plots that prompt the reader to ponder important, essential life questions. Conflict that keeps the pages turning.

I didn't think these novels were just for 9-12 year olds! They're compelling, deep, heartfelt, poignant, real stories with true-to-life characters that get under your skin. Plots that prompt the reader to ponder important, essential life questions. Conflict that keeps the pages turning.Could I create something like that?

I read them several times. I studied them. I learned what ingredients made up a good story for this age group.

I tried to write a middle grade novel. Fail (of course). I wrote another. Fail #2. Those documents are stored safely on my computer and they're not going anywhere. I think of them as practice books, sort of like an archeological remnant of early cave drawings. But, like those plucky heroines in the two books who are determined to pursue answers, I kept at it. And at some point, something worked. I wrote something that got a nibble. Then a deal!

This month, my fourth middle grade novel will be released from Aladdin Books, Ethan Marcus Makes His Mark. It's a sequel to last year's Ethan Marcus Stands Up. I had such fun with these two books, which are narrated by five seventh-graders, digging into themes of determination, sibling rivalry, and learning to get along with others who see the world from a different lens.

I don't think I've quite yet reached the level of Deborah's and Sarah's extraordinary works, but I keep trying. I continue to be inspired by them and so many other middle grade authors.

There's no other writing world I'd rather be a part of.

Michele Weber Hurwitz is the author of Calli Be Gold, The Summer I Saved the World in 65 Days, Ethan Marcus Stands Up, and Ethan Marcus Makes His Mark. Catch up with her at micheleweberhurwitz.com.

Published on November 14, 2018 05:00

November 12, 2018

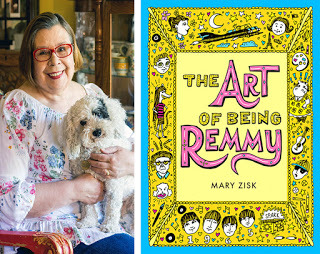

Book Review: THE ART OF BEING REMMY by Mary Zisk

I recently read a fun book that was an entertaining trip down memory lane. THE ART OF BEING REMMY by Mary Zisk takes place in 1965 during the height of the Beatles fame in the USA. The heroine Remmy Rinaldi, who wants to marry Beatle Paul (she wasn't the only one!), also aspires to be an artist against the wishes of her father. The only way she can prove to Dad that girls can be artists too, is to win the Art Competition.

Here's my review of this delightful and funny story:

The Art Of Being Remmy by Mary Zisk is a delightful time travel trip back to 1965 when the Beatles reigned supreme. Remmy Rinaldi and her best friend Debbie ADORE all things Beatles and make a plan to one day meet their idols. Remmy also loves art and has a second secret plan to develop her Spark as an artist, even though it means going against her father’s wishes. Girls in the 1960’s need to know their place and follow the path men have set for them. A path that includes being housewives, mothers, maybe teachers, nurses , secretaries or stewardesses. But artists? NEVER!

Remmy is determined to prove her father and everyone else – including her once friend Bill – that she can be a great artist. Good enough to win a contest. She keeps her drawings in Super Secret Sketchbooks and earns her own money to take painting lessons so she can enter the Art Awards Contest.

Lots of challenges get in the way of Remmy’s plan, including problems with her best friend and a devious French Rat Fink. Along the bumpy road of 7th grade, Remmy learns that some rules are worth challenging and fairness for girls in all aspects of life is one of them.

This illustrated middle grade book is a funny and charming peek into the days when the Beatles took the world by storm and the force of female protest was at their heels. An entertaining read that celebrates creativity and girl power.

Darlene Beck Jacobson

Here's my review of this delightful and funny story:

The Art Of Being Remmy by Mary Zisk is a delightful time travel trip back to 1965 when the Beatles reigned supreme. Remmy Rinaldi and her best friend Debbie ADORE all things Beatles and make a plan to one day meet their idols. Remmy also loves art and has a second secret plan to develop her Spark as an artist, even though it means going against her father’s wishes. Girls in the 1960’s need to know their place and follow the path men have set for them. A path that includes being housewives, mothers, maybe teachers, nurses , secretaries or stewardesses. But artists? NEVER!

Remmy is determined to prove her father and everyone else – including her once friend Bill – that she can be a great artist. Good enough to win a contest. She keeps her drawings in Super Secret Sketchbooks and earns her own money to take painting lessons so she can enter the Art Awards Contest.

Lots of challenges get in the way of Remmy’s plan, including problems with her best friend and a devious French Rat Fink. Along the bumpy road of 7th grade, Remmy learns that some rules are worth challenging and fairness for girls in all aspects of life is one of them.

This illustrated middle grade book is a funny and charming peek into the days when the Beatles took the world by storm and the force of female protest was at their heels. An entertaining read that celebrates creativity and girl power.

Darlene Beck Jacobson

Published on November 12, 2018 06:05

November 11, 2018

No One Single Mentor for Me

by Jody Feldman7th grade, Home Ec*

The mandatory class was divided into sewing and cooking.

The sewing? I choose to forget that fiasco.

But the cooking? I had that down pat. Learning at the heels of my mother and grandmothers, not only did I already understand how to follow a recipe, I also understood how to stray from one to get even better results. I can tell you stories about how I got a B- in eggs because I refused to play by the classroom rules and an Incomplete in a homework assignment for the same reason, but I should probably explain why this pertains to this month’s theme... and my next sentence.

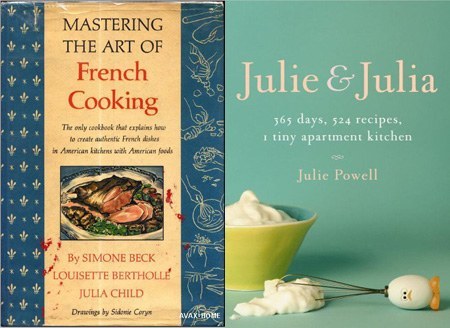

I am not Julie Powell. Who’s that?

She’s the author of Julie and Julia**, the woman who chronicled her year-long journey cooking all 524 recipes in Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking.

I own that cookbook, and I’ve cooked recipes from it, but I would never even entertain the idea of learning how to cook from one book. You don't see Julia Child making strudel or matzoh balls or mushroom risotto here.

As much as I’ve set out to study what works for authors I admire, and as well as I understand how to use books as mentor texts, I find that I learn even more by experiencing books as stories. I am not wired to follow one person’s methods or lessons or examples to raise my skills to the next level.

It’s taken a village to educate me. It’s taken (off the top of my head) Cinda Chima, Debby Garfinkle, Mary Beth Miller, Martha Levine, Cindy Lord, Gordon Korman, Louis Sachar, Vicki Jamieson, Frank Cottrell Boyce, Rebecca Stead, Eugene Yelchin, Cynthia Leitich Smith, Franny Billingsley, Nancy Werlin, Agatha Christie, Patricia McKissack, Dr. Seuss, Roald Dahl, Eve Bunting, and uncountable more—in their roles as critique partners or conference presenters or story creators or all three—to help me move my skills along. And I have to believe that it’s this patchwork of unofficial mentors that has most helped me to develop a style I can call my own.

The way I’m wired, it would never have taken a single Home Ec instructor to teach me how to cook. Or a single cookbook. Or even Julia Child. (I even learned something about cake decorating from my father.) Besides, I have way too much fun absorbing bits and pieces, learnings and lessons, ideas and inspirations wherever I happen to find them.

*****************

*Now known in most schools as some version of FACS—Family and Consumer Science.

**You may know it better as its film adaptation starring Meryl Streep and Amy Adams.

The mandatory class was divided into sewing and cooking.

The sewing? I choose to forget that fiasco.

But the cooking? I had that down pat. Learning at the heels of my mother and grandmothers, not only did I already understand how to follow a recipe, I also understood how to stray from one to get even better results. I can tell you stories about how I got a B- in eggs because I refused to play by the classroom rules and an Incomplete in a homework assignment for the same reason, but I should probably explain why this pertains to this month’s theme... and my next sentence.

I am not Julie Powell. Who’s that?

She’s the author of Julie and Julia**, the woman who chronicled her year-long journey cooking all 524 recipes in Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking.

I own that cookbook, and I’ve cooked recipes from it, but I would never even entertain the idea of learning how to cook from one book. You don't see Julia Child making strudel or matzoh balls or mushroom risotto here.

As much as I’ve set out to study what works for authors I admire, and as well as I understand how to use books as mentor texts, I find that I learn even more by experiencing books as stories. I am not wired to follow one person’s methods or lessons or examples to raise my skills to the next level.

It’s taken a village to educate me. It’s taken (off the top of my head) Cinda Chima, Debby Garfinkle, Mary Beth Miller, Martha Levine, Cindy Lord, Gordon Korman, Louis Sachar, Vicki Jamieson, Frank Cottrell Boyce, Rebecca Stead, Eugene Yelchin, Cynthia Leitich Smith, Franny Billingsley, Nancy Werlin, Agatha Christie, Patricia McKissack, Dr. Seuss, Roald Dahl, Eve Bunting, and uncountable more—in their roles as critique partners or conference presenters or story creators or all three—to help me move my skills along. And I have to believe that it’s this patchwork of unofficial mentors that has most helped me to develop a style I can call my own.

The way I’m wired, it would never have taken a single Home Ec instructor to teach me how to cook. Or a single cookbook. Or even Julia Child. (I even learned something about cake decorating from my father.) Besides, I have way too much fun absorbing bits and pieces, learnings and lessons, ideas and inspirations wherever I happen to find them.

*****************

*Now known in most schools as some version of FACS—Family and Consumer Science.

**You may know it better as its film adaptation starring Meryl Streep and Amy Adams.

Published on November 11, 2018 06:11

November 8, 2018

Philip Pullman's Alethiometer -- by Jane Kelley

I just finished reading the first novel of Philip Pullman's new trilogy, The Book of Dust. He is a master storyteller. I know I should have read the book slowly, to decipher how his realistic characters can thrive in such imaginative, suspenseful plots. But I couldn't. I devoured all 450 pages. So I have started reading it again in hopes of learning how he does what he does.

Reading his interviews have given me a few hints. He described his workspace as having room for lots of books and several power tools. It isn't hard to picture him actually constructing things, like the canoe which is such an important part of the novel I just read. He is a craftsman. And so whenever he describes something he has imagined, like the alethiometer, the mechanisms are so clear that I believe I could actually hold one in my hand.

The name alethiometer comes from two Greek words. Aletheia means truth. Meter means to measure. The characters in this novel and in his earlier trilogy, His Dark Materials, use the alethiometer to guide them.

The device resembles a compass or a clock face with 36 symbols around its circumference. It has four hands. To ask it a question, you point three of the hands at three separate symbols. Then the fourth hand will spin until it points to a fourth symbol. These images provide the answer. Some people, of course, are better at reading it than others. Those who think they already know have a harder time arriving at the truth. What works best, as one of the characters says, is to hold the question in one's mind while simultaneously letting the mind drift toward discovery.

That's exactly how I try to write. I select several separate symbols. I hold them in my mind (and also my heart). I let my mind roam around all the possibilities of what they suggest. And eventually, unless my thinking has become clogged by the predictable, the short-cut, or the trope, I arrive at a truth.

But of all the elements that he uses, my favorites are the daemons.

He has said that His Dark Materials and The Book of Dust are not fantasies, but stark realism. He writes about "real people, like us, and the story is about a universal human experience, namely growing up. The fantasy parts of the story were there as a picture of aspects of human nature, not as something alien and strange. For example, readers have told me that the daemons, which at first seem so utterly fantastic, soon become so familiar and essential a part of each character that they, the readers, feel as if they've got a daemon themselves. My point is that we all have. It's an aspect of our personality that we often overlook, but it is there. I was using the fantastical elements to say something that I thought was true about us and about our lives."

Yes. That's it. That's exactly what I want to do. Maybe I should get some power tools? Or maybe just read his collection of essays for more insights.

Published on November 08, 2018 04:00

November 5, 2018

What I Learned From Kate DiCamillo by Deborah Lytton

I wish I could say that Kate DiCamillo is a close personal friend and that we have talked about books and writing over cups of tea at my favorite gluten-free, vegan cafe. But I can't.

What I can say is that Kate DiCamillo has taught me a tremendous amount about writing through her books. I study her craft as I read her stories, and I try to incorporate the lessons I have learned from her in my own work.

Ms. DiCamillo's gift of storytelling balances emotion with story so that one never overpowers the other. Keeping readers engaged can make the difference between a manuscript that finds a publishing home and one that will live forever at the bottom of a desk drawer. It is the story that makes a reader want to turn to the next page, just to see what will happen. And yet, story without emotion will fail to have a lasting impression. THE MIRACULOUS JOURNEY OF EDWARD TULANE combines moving details with a compelling story all told using beautiful spare prose. Kate DiCamillo shows us in all of her works that words can be pieced together to create art and story. In BECAUSE OF WINN-DIXIE, she demonstrates all of this as well as the way secondary characters need to have their own backstories and character arcs in order to balance the main character's journey.

Through her books, Kate DiCamillo has taught me many lessons about story structure, character development, and word choice, but most of all, she has taught me to keep writing. Because she continues to challenge herself to create new and inventive stories that touch the heart and make lasting impressions on all her readers, young and old.

What I can say is that Kate DiCamillo has taught me a tremendous amount about writing through her books. I study her craft as I read her stories, and I try to incorporate the lessons I have learned from her in my own work.

Ms. DiCamillo's gift of storytelling balances emotion with story so that one never overpowers the other. Keeping readers engaged can make the difference between a manuscript that finds a publishing home and one that will live forever at the bottom of a desk drawer. It is the story that makes a reader want to turn to the next page, just to see what will happen. And yet, story without emotion will fail to have a lasting impression. THE MIRACULOUS JOURNEY OF EDWARD TULANE combines moving details with a compelling story all told using beautiful spare prose. Kate DiCamillo shows us in all of her works that words can be pieced together to create art and story. In BECAUSE OF WINN-DIXIE, she demonstrates all of this as well as the way secondary characters need to have their own backstories and character arcs in order to balance the main character's journey.

Through her books, Kate DiCamillo has taught me many lessons about story structure, character development, and word choice, but most of all, she has taught me to keep writing. Because she continues to challenge herself to create new and inventive stories that touch the heart and make lasting impressions on all her readers, young and old.

Published on November 05, 2018 18:46