Grant McCracken's Blog, page 8

April 21, 2016

how to make TV now (the “whole world” approach)

Natalie Chaidez is the show runner for Hunters (Mondays, 10:00 eastern, SyFy). Recently Sean Hutchinson asked her what she was aiming for.

Our idea of aliens is cliched, she replied. She wanted to “flip everything you think you know going into an alien series.”

Mission accomplished. The aliens on Hunters are not your standard-issue “monsters from outer space.” Monsters, yes, but complicated monsters. We can’t quite tell what they are up to. Bad stuff, yes. But the exact what, how and why of their monstrosity is unclear.

Chaidez explains:

I wanted to do something different. That led me to a neurologist from Brown University named Seth Horowitz, and he and I collaborated about the planet, their anatomy, and how they’d operate on earth. It gave it a level of originality because we approached it from the inside out.

Hutchinson:

Why did you want to dive in and be that thorough if most people won’t know those details?

Chaidez:

Because it’s fun! But you also just want to know so it feels cohesive. 90 percent of the stuff Seth and I talked about will probably never make it into the show.

This is interesting because it breaks a cardinal rule of the old television. And this is do exactly as much as you must to fill the screen…and not a jot more. To invent a world and leave 90% of it un-shot, well, we can just imagine the reaction of a standard-issue producer.

“It’s my job to make sure shit like this never happens! [Wave cliche cigar in air for emphasis] Artists! You have to watch ’em every goddamn second!”

This is a parsimony rule of the kind that capitalism loves. No expenditure must ever be “excess to requirement.” Some producers are uncomplicated monsters. It’s their job to make sure that creative enterprises are starved of the resources necessary to turn popular culture into culture. It’s what they like to call their “fiduciary obligation.”

The parsimony rule helps explain that dizzying sensation we get when we go to a TV production or a film set, and notice how “thin” everything is. Not rock but papermache! Not an entire world but just enough of it. An universe made to go right to the edge of what the camera can see, and not an inch beyond.

What Chaidez and Horowitz have done goes completely beyond requirement. They made an entire world, much of which we will never see.

Why?

This could be a case of the recklessness of the new TV. With the rise of the showrunner, people are no longer making TV as half-hour sausages. They have bigger ambitions and sometimes bigger pretensions. Budgets will bloom!

Or is there something going on here?

I think the Chaidez-Horowitz approach, let’s call it the “whole world” approach, has several assumptions (each of which, if warranted, is a way to justify additional expenditure):

1. A pre-text is better than a “pretext”

Our standards of richness, complexity and subtlety on TV have risen. “Thin” TV is now scorned. We want our culture to feel fully realized and in the case of the story telling, this means that we want the story to feel as if it predates the production. Novelists are good at this. But TV, ruled by cigar-waving producers, has been less good. Too often, the story world feels served up. Something tells us that it will disappear the moment the narrative has moved on, that it will cease the moment the camera is sated. (For the pre-text impulse in the worlds of computers and cuisine, see my post of Steve Jobs and Alice Waters and their “exquisite choice” capitalism.)

2. a “whole world” approach is generative of fan interest

When we sense that the showrunner has taken a whole world approach, we engage. Shafts of light show through. We begin to try to construct the whole world from the available evidence. (We used to do this at the Harvard Business School. We would give students pieces of the spread sheet which they would then reconstruct.)

The “whole world” approach is a great way of turning viewers into fans. The moment we detect a whole world behind the narrative, we rouse ourselves from couch potato status and begin to examine faint signals very carefully. What does this stray remark tell us? If X, then we can assume the larger world looks like this. But if Y, we can construct something altogether different. (Remember when Star Trek viewers began to map the ship. The showrunners were astonished.) This is astounding engagement, one that every showrunner dreams of. And all we have to do, it turns out, is engage in complete acts of invention instead of “good enough for television” ones. And “good enough for television” (aka “partial world” TV) is a place no one wants to live anymore. It’s always less than the sum of its parts. That way lies creative entropy and fan discouragement.

3. a “whole world” approach is generative of fan fiction

Whole worlds made available in shafts of light invite something more than engagement. They say to the transmedia fan, “here’s a place to start. Make this glimpse your point of departure. Or that one.” Whole worlds make a thousand flowers bloom. And this too is the stuff of showrunner fantasy. To have fans who love your work so much they seek to invent more of it. To make work so provocative it sends fans racing to their key board, can there be any greater compliment? There is a whole world paradox, too. It says “the more complete your world, the more worlds it will help birth.”

4 a “whole world” approach is generative of transmedia

As Henry Jenkins has helped us see, transmedia is that extraordinary creation in contemporary culture where certain stories are so prized, they attract many authors. Eventually, the “one true text” gives way to a story that lives in all its variations, on all its media. Now that our whole world is generating lots of fan fiction, it has like William Gibson’s Mona Lisa, slipped the confines of a single medium and put out into a vastly larger imaginative universe. Another paradox then. World worlds give rise to an entire universe. No, our cigar chomping producer cannot “monitize” all these variations but really that’s no longer the point. This will come…but if and only if you make something that our culture decides is worthy of its contributions. The life of a cultural “property” depends as Jenkins, Ford and Green say, on the willingness of the fan to distribute it. But as I was laboring to say yesterday, it also depends on the willingness of the fan to contribute to it.

It’s hard to write this post and not think how much it evokes the spirit of USC. First, there’s Henry Jenkins, Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, Cinematic Arts, and Education at the USC Annenberg School. Then there’s Geoffrey Long, recently appointed Creative Director for the World Building Media Lab at USC. Geoffrey is my guru when it comes to the question of building worlds. And just today, I got the very good news that Robert V. Kozinets has been appointed the Jayne and Hans Hufschmid Chair in Strategic Public Relations and Business Communication at USC.

I am sometimes asked where people should go to study contemporary culture. Now I know.

April 19, 2016

The ‘wicked grin’ test (as a new creative measure)

How do you know when something in our culture is really good?

I think it’s when it makes us grin a wicked grin.

This is one of those: Dave Chappelle does imitation of Prince and Prince uses the imitation for his album cover. Dave becomes Prince. Prince becomes Dave becoming Prince.

For post-modernists, this is ‘signs circulating.’ Fair enough but not very interesting. It doesn’t explain why we grin wickedly.

It’s the relocation that does it. Daveness taking on Princeness. Princeness taking on Daveness as Princeness. These are meanings in motion. We grin wickedly because we can’t believe that Dave dared attempt Princeness. It’s not temerity that gets us. Dave is free to make fun of a genius like Prince. That’s the privilege of his genius.

No, what makes us grin is astonishment. How did Dave do it? How is that possible? Daveness and Princeness share a claim (and a proof) of genius, but they come from very different parts of our culture. They are in a sense incommensurate.

And they just made themselves (for a moment, in a way) commensurate. This makes our minds happy…and our faces grin. I think it is at some level it makes our brains happy. Meanings attached to one thing now, astonishingly, belong to another. We can feel gears turning in our heads.

Dave and Prince have brought meanings together that are normally kept apart. And we thank them for this semiotic miracle by grinning our admiration, astonishment, gratitude. Who knew our culture could do that.

We make a lot of culture with acts of unexpected, unprecedented combination. (I have tried to map this process for contemporary culture in a book called Culturematic.)

Indeed, wicked grinning should be the new objective not just of comedy and album cover design, but of branding, design and advertising. We used to slavishly obey the rules of official combination (aka genre). Now we bore people with this predictability. If the user, viewer, consumer, audience can see where we’re going, they won’t come with us. (Susan Sarandon did an interview yesterday on Charlie Rose in which she said precisely this.)

Compare a culturematic to old fashioned marketing. The ad man and woman came up with a blindingly obvious message, stuffed it into one of the mass media (3 network TV, magazines, newspaper, radio) and fired it at the target over and over again until our ears bled. Everyone just wanted the “persuasion” to stop. This was cold war torture. And the worse part of this torture was how completely unsurprising it all was.

Every thing changes when we assume that our “consumers” are clever and interesting, and, chances are, making culture on their own. This means first that they can see the grammars we are using. Second, it means that they are looking for culture to make their own, for critical purposes and creative ones. Culture creative, assume you are talking to someone has smart as you are. Assume you are talking to someone who can do what you do. And go with the idea that we have no hope of success unless we are making content that makes people grin wickedly.

Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford and Joshua Green have invited us to embrace a new slogan: “if it doesn’t spread, it’s dead.” The idea is that a message will die unless people take an act hand in distributing it by social media. I am proposed that before we apply the Jenkins-Ford-Green test, we apply “wicked grin test.” Forget the focus groups and the audience testing. Just show your work to someone and look at the expression on their face.

April 12, 2016

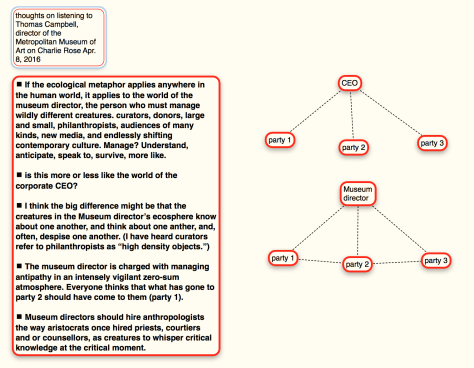

How to manage many stakeholders

A note on style: I wrote this in a hotel room somewhere. I used Scapple from Literature and Latte to do it. It was really just a note to myself. But then I thought, “maybe this is a better, more visual, way to present the post.” Tell me what you think about the form as well as the content, please.

A note on style: I wrote this in a hotel room somewhere. I used Scapple from Literature and Latte to do it. It was really just a note to myself. But then I thought, “maybe this is a better, more visual, way to present the post.” Tell me what you think about the form as well as the content, please.

March 30, 2016

Flight 1095

Coming home from Phoenix on Friday, I found myself sharing the plane with Aidy Bryant, Vanessa Bayer, and Bret Stephens. Bryant and Bayer are SNL players. Stephens (below) is Foreign Affairs columnist at the Wall Street Journal.

I am guessing Bryant, Bayer, and Stephens have different views of the world. (This is a guess, but I am comfortable working by the “available light” of SNL and WSJ.)

I am guessing one difference of opinion turns on their ideas of America.

Bryant and Bayer taunt us for the sexism that diminishes men and women. Both of them excel at the performance of a certain “sweet-faced” agreeableness, occupying stereotypes the better to destroy them.

Stephens, on the other hand, is a student of the American presence abroad, and especially alert to how it serves the cause of reasonableness in a world where fundamentalism now routinely makes reason almost impossible to obtain. (See his excellent book: America in Retreat.)

Not such different projects, after all. We could say these three Americans stand for different versions of liberty, that most American idea. Bryant and Bayer champion personal liberty and the notion that it is the right of individuals to choose personal identity, (and not have it forced upon them). Stephens champions political liberty and the notion that it is the right of individuals to choose collective identity, (and not have it forced upon them).Both oppose the enemies of liberty.

And they work together. Stephens insists on America as a “city on a hill” that promises liberty to those held captive by other polities, even as Bryant and Bayer keep the “city” true to its mission and investigate what happens to identity once gender stereotypes are thrown off. (First political liberty, then cultural liberty.)

To this extent, these three are all “on the same plane.”

But things, I think it’s fair to assume, end there.

When it comes to the presidential race, Bryant, Bayer and Stephens have much less in common. I guess that Bryant and Bayer favor Hilary, if not Sanders, while Stephens favors Cruz, but not Trump. (A man who cares this much about foreign affairs could not vote for a Donald Trump who, as the joke has it, doesn’t know who the prime minister of Canada is. We don’t need “available light” for this one, first principles will do.)

This difference makes a difference. Now these three, with so much in common, begin to press in opposite directions. Eventually, what they share, like the rest of American politics, begins to tear and perhaps eventually to vanish. I expect the political science of this problem is well charted. I want to comment on the anthropology.

Consider what might have happened had Bryant, Bayer and Stephens struck up a conversation on flight 1095. (As far as I know, they didn’t. They weren’t seated together. And, to my great regret, they weren’t seated with me.)

What would have happened to this conversation? Once they got beyond the pleasantries, was there common ground? Or are we now living with pockets of difference so different that mutuality is now in peril. This is what scares the anthropologist.

We could use comedy to construct a continuum. In a fully mutual culture, every one “gets” the joke as a joke. In a culture of failing mutuality, there are some people who don’t get they joke but they do at least understand that a joke was intended.

We have a linguistic convention here. The person who loves the joke looks at the person who has a puzzled expression, and asks, “You get the joke, right?” And the puzzled person says, “Oh, I get it. I just don’t think it’s that funny.” At this point, we know there is some noise in the cultural system, but only some. Not all jokes are fungible. But all jokes are visible.

Then there is the third stage, the one we may be approaching now, and that’s when the puzzled person can’t tell that a joke was intended. (Some of Sarah Silverman’s jokes strike me that way. I am of course joking.) The puzzled person (me) is as if from another culture,. They do not share an idea of what “funny” (at least in this case) is. Somebody does something. Other people begin to laugh. Now when asked, “You get the joke, right?” the puzzled person replies “Um, no, I don’t. It’s funny? What’s funny?”

Sometimes when we storm at one another on the political stage, I wonder if this is not a theater made out of the narcissism of small differences. Really, we are just seizing on our differences as an opportunity for a jolly good shouting match. And who doesn’t like a shouting match.

But sometimes you have to wonder whether we are approaching a stage in which we are no longer (or less) mutually intelligible. You could argue that it is the unacknowledged task of SNL and the WSJ to craft a commonality, to help build a shared language, shared values, as we go. And sometimes this appears to work quite well. But other times we are looking at the emergences, driven in part by the creative efforts of SNL and the WSJ, where small quantitative differences add up to big paradigmatic jumps. We start to separate.

There is no narcissism of big differences. The “jolly” and the “good” disappear. Then it’s strangers on a plane. Mutuality is now fugitive. (Having taken another flight.)

Here’s one possibility, that there is something about our present political process that is really perilous in the present moment. It’s an old system, designed to make it possible to capture the political will when people are scattered across a continent. This politics is a Mississippi whether tiny differences in the hinter land are driven to aggregate until at the end of the day we have two parties and a few ideas. This aggregating process was valuable when the country was so geographically disaggregated. But now that we are so cultural disaggregated, it may force contests and oppositions where these are unnecessary.

Force us to make simple choices, and we rush to opposite sides of the ship of state. Find some way to capture the political will(s) in a more nuanced way, and we might escape we some of the enmity and the shouting match. (Now we are back in the realm of political science, and the anthropologist must defer to its better judgment.)

March 3, 2016

An interview with Noemi Charlotte Thieves

I had a chance to interview Noemi Charlotte Thieves on January 10. We were at a going-away party in Brooklyn and fell into conversation. The conversation was SO INTERESTING that I asked Noemi if we could step outside so that I could capture our conversation on my iPhone. (The ethnographic opportunity is always now.)

Of course, it wasn’t as simple as that. We had to find a fire engine and cue the fire engine and the driver couldn’t hit his mark. Finally we just had him drive into frame. I mean does the NYFD not give these people ANY media training? (We love. We kid.)

Noemi was wonderful to interview, an ethnographer’s dream, a gift from the gods of ethnography. He’s thoughtful, clear, vivid, expansive, intelligent, and illuminating.

I think Noemi is perhaps also a glimpse of the culture we’re becoming.

This interview 20 years ago would have been painful and sad. We were a culture of two solitudes. Filmmakers could be popular or they be experimental. And they were tortured by the choice. They were forced to choose one side or the other.

Sometime in the last 10 years, the two extremes began to draw together. (And ironies of ironies, this was roughly the period in which the two extremes of American politics began to drive apart.) Genre and art have yet to find one another, but, as Noemi points out, the hunt is on.

So far, as Noemi also points out, it’s been a happy rapprochement. The popular stuff, while democratic and accessible, was obvious to the point of being laborious and “jump the shark” awful. And the artistic work was, too often, obscure. It was, actually, as the phrase has it, “deservedly obscure.” (There was a time when Canadians refused to watch anything that came from the National Film Board. They were effectively boycotting the work they were as taxpayers helping to fund.)

To combine the two extremes is to begin to construct a single American culture, a place where democratic clarity and artistic risk work together. Now, we have to figure out what to do about the politics.

(Thanks to Jeremy DiPaolo and Katie Koch for the introduction to Noemi. (How is Sweden?))

February 24, 2016

The rise of a celebrity culture

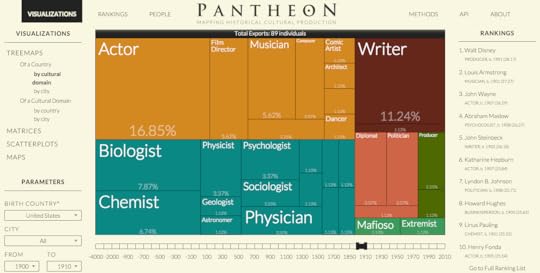

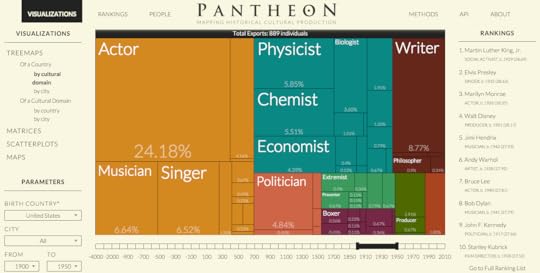

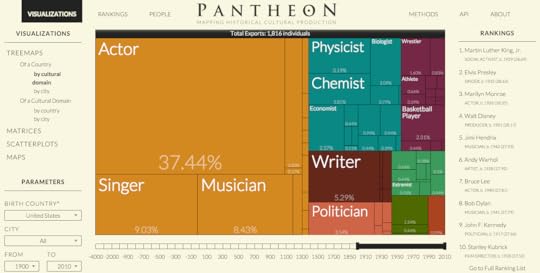

These images are from the Pantheon database at the Macro Connections group at Media Lab at MIT. They map what the Media Lab calls “historical cultural production” and the relative proportion of famous people by time, place and category.

I asked the database to report on fame in the US for three periods:

1900 – 1910

1900 – 1950

1900 – 2010

The most striking results:

Mattering more:

actors

singers and musicians

athletes

Mattering less:

writers

natural scientists and other academics

US in the period 1900 – 1910

US in the period 1900 – 1950

US in the period 1900 – 2010

The glib thing to say is that the sky is falling, that we are a culture that cares more about celebrities than “serious people” and this must be taken as a measure of our essential triviality and an indication that the end is nigh.

Intellectuals especially like to recite the line from Daniel Boorstin’s The Image, the one that says that too many of our celebrities are “famous for being famous.” And it feels nice to stand on our high horse and scorn contemporary culture, but it’s not very instructive or intelligent. It just makes us feel good.

In point of fact, no one is famous for being famous. At a minimum they speak to and for something in our culture, and only thus do they climb from the obscurity that otherwise holds the rest of us captive (and especially and increasingly scornful academics). (Boorstin was a fine and incredibly useful historian but this his most memorable phrase was not his best moment. I believe it stands as a Kuhnian confession of the limits of his paradigm, as if to say, “I can’t understand celebrity so I am going to say it isn’t anything.” Historian, heal thyself.)

An anthropological point of view obliges us to take a culture at its face and reckon with what it is, not what we think it should or shouldn’t be. This work has yet to be undertaken, but a few notes:

Celebrities serve at our collective pleasure in a way that other elites do not. When we are done with a celebrity we are so very done with them. Now we scorn them as “has beens.”

Celebrities are superbly adaptable. We need a different model of selfhood, a new version of maleness, a transformed model of what is “funny,” “charming” or “tragic,” there is an actor out there somewhere who is prepared to serve. This makes celebrity culture a useful “complex adaptive system” in the language of complexity theory. We can swap in the new, and swap out the old, easily and without any real cost (to us). (The cost to celebrities of our capriciousness is cruel. Do we care? We don’t care. We make French monarchs look like models of compassion.)

Individual celebrities are sometimes highly experimental and we should signify this as the US Air Force does with an “X.” When an airplane is called the X15 the Air Force is warning us that it is experimental and not to be completely surprised if it falls from the sky. Why not call him XRussellCrowe (and watch for flying telephones).

Source: Yu, A. Z., et al. (2016). Pantheon 1.0, a manually verified dataset of globally famous biographies. Scientific Data 2:150075. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2015.75

Thanks to the Macro Connections group at MIT.

Give the database a spin here.

Thanks to Thomas Ball for the find and the head’s up. Hat’s off to Cesar Hidalgo and the Media Lab. We have too little data on culture in motion and America is nothing if not a culture in motion.

February 23, 2016

Craig Young: an interview in SF

I did this interview for a project called Automated Anthropologist. (I went to San Francisco and let it be known that I was prepared to do anything anyone told me to do, within the limits of morality, legality, and being Canadian.)

With the help of Maria Elmqvist (now a Strategic Planner at Perfect Fools in Amsterdam), I talked to Craig Young.

I like this interview for a couple of reasons but chiefly it’s Craig. Really clear, forthcoming, and helpful. I paid him, so I was making some small contribution to his economy. But he went above and beyond the call. (Maria and I approached another guy for an interview and he said, “not so much” in a way that sounded unmistakably like “go f*ck yourself.” Craig’s generosity was especially welcome.)

Another thing I liked about the interview was the glimpse it gives of city life. In this case, of the invisible distinctions of space that are perfectly clear to Craig and a surprise to the rest of us (if and when discovered by the rest of us). The world is filled with this invisible distinctions. They surround us all the time. The secret of ethnography: keep an eye out. Ask everyone.

A third point to make is methodological. Interviews a guy like Craig is difficult because you are (I am) concerned that you are (I am) going to ask something insensitive. In addition to invisible spaces, there are invisible sensitivities, and the last thing you (I) want to do is blunder into them.

Hence my tone, which is deliberately convivial, kinda loud, and bit clueless. The cultural logic is this: if this guy (me) is incapable of certain subtleties, he may give offense, but he doesn’t mean to give offense. (We may think of this as the “big stupid labrador” defense.) I know this is counter-intuitive, but then it is a cultural logic, not a logical logic. Ironically, the more you signal an effort not to give offense (by agonizing over choice of words and so on), the more likely you are to give offense.

A fourth point, this one moral: there are people in the research community who believe that an interview with Craig offends morally and politically. The notion is that I am taking advantage of a power asymmetry. Yes, it’s true, asymmetries raise the possibility of exploitation. And then it’s incumbent on me to see and say what my motives were. The answer is that for the purposes of Automated Anthropologist I was talking to anyone who would talk to me. Did I take more than I gave? That’s a tough one. I paid Craig. So there was an exchange of value. Only Craig can decide whether he was properly compensated. The danger is that if we decide that we shouldn’t interview Craig for political reasons, he is denied the engagement and the pay. I think it’s for Craig to decide whether he wants to do the interview, and to remove this choice from him really does enact a power asymmetry. Apparently, we know better than he does. We decide for him. But this is not an easy issue.

A fifth point: I am glad to know even a little more about Craig and what life is like in the street. The idea of having to worry about people “stealing your stuff” is a revelation. I can’t imagine this order of disorder in my life. It’s all interesting to see that there is more order than I would have expected, certain work arounds, a schedule, a support network. All of these discourage the idea I tend to have of life on the street, that it is radically unstable and always on the verge of the cataclysmic. And I guess that’s one thing to take away from the interview, that life on the street is both quite stable and always on the verge of the cataclysmic.

A sixth point: the defense of this interview, the defense of all ethnographic work, is perhaps that the other is a little less other. I don’t think I carry diminishing ideas of people who live in the street. (I don’t romanticize them. I don’t blame them.) But it’s also true that, beyond that, I don’t know what to think. Ethnography, even a very brief interview of this kind, helps give us access to one another. And this is a necessary condition, I think, of empathy and aid.

One last point, everyone with a smart phone is now in possession of a fantastically good piece of recording technology. I wish I were doing more of these interviews. I wish we all were.

Post script: thanks to Maria Elmqvist who did the camera work and participated in Auto Anthro with intelligence and a real ethnographic sensitivity.

February 22, 2016

Bud Caddell

Whenever I have the chance to talk to Bud Caddell, I take it. This’s because while I know the future is badly distributed (in Gibson’s famous phrase), I fervently believe it must be somewhere in the near vicinity of Bud Caddell.

In this 10 minutes of interview, Bud talks about the following things

00: 37:00 mark (~) that with his new company Nobl Collective, he is learning how to configure the culture inside a company to articulate it with the culture outside the company.

00:58:00 the digital disruption changes these things in succession

culture

how brands communicate

how products are made

the teams within the organization

1:39 On joining the world of advertising and why he left.

3:43 the thing about that very famous Oreo campaign (that it took 6 different agencies, and a lot of money). This was not the “safe to fail” experiments the world now holds dear.

4:20 companies are having to learn to both optimize and futurecast, and that these are opposing challenges.

6:00 there is a tension in the corporation between pushing the innovation team too far away or holding it too close. (Amazon is the case in point.)

6:43 Nobl believes that companies take human choice away from teams. The point of Nobl is to restore that choice.

10:20 Bud is concerned that, all the noise to the contrary, we are actually moving away from small startup entrepreneurialism. Bigness is not dying, it’s once more on the rise.

11:56 Bud is concerned that with this culture inside, the culture outside (i.e., American culture) could narrow and something like a 50s monoculture

11:18 organizations are inclined to treat employees like errant children or robots. The point of the exercise find their strength, not assume their weaknesses. Give them autonomy. (Because they can’t navigate the future, they can’t create value, without that autonomy. My words, more than Bud’s. Sorry!)

??:?? Nobl aims to construct core teams with 4 properties

customer obsessed (prepared to “leave the building” to find out more

closely aligned with one another

autonomous, free to discover an idea and test it

organized by simple rules

Thanks to Bud for the chance to chat.

I am hoping to do more of these interviews. My assumption is that we are all works in progress working on a work in progress in a work in progress, and that to listen to one another as we configure works1, works2 and work3 is interesting.

One last note on method. This interview might stand as a grievous example of “leading the witness.” I was shocked when listening to it again to hear that my questions were more about me and less about Bud. Yes, you have to start somewhere. And yes, inevitably you are going to speak from what you know. But the very point of ethnography and the thing it does so well is to discover things you don’t think and hadn’t ever thought to think. It’s always a chance, more vividly, to get out of our heads into that of the respondent. Or to put this another way, I was insufficiently curious in this interview.

December 23, 2015

Use All Five interviews Grant McCracken

This is an interview that Zsa Zsa (left) and I did recently with Ryan Ernst at Use All Five. Thanks, Ryan.

December 15, 2015

Screw the gift economy, a reply to Clay Shirky

I came across a post today by Gaby Dunn called “Get rich or die vlogging: The sad economics of internet fame.” Dunn gives us YouTube and Instagram celebrities forced to live hand to mouth. It reminded me of an essay I wrote months ago, shelved and then forgot. Here’s a piece of the larger whole.

Consider this crude calculation. Let’s posit 100 people each of whom is producing 10 artifacts a year for the digital domain. (Artifacts include blog posts, fan fiction, web sites, remixes, podcasts, fan art, Pinterest pages, and so on.) We are going to assume that these creative efforts are funded by day jobs, scholarships, and parental support. With this subvention, this “gift economy” produces 1000 artifacts a year. Some of this work is rich and interesting.

The creators are rewarded for their work with acknowledgment and gratitude. The exchange is ruled by what the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins would call “generalized reciprocity.” (See his Stone Age Economics.) Gifts are given without expectation of immediate or exact return. There is lots of cultural meaning here but no real economic value.

Let’s release economic value into the system. Now, the best work costs. We pay for ownership or for access. We could even use a “tipping” system. When we admire a piece of fan art, we tip the creator. This tip could come out of the $5 our ISP returns to us from our subscription fee. Or it could be supplied to us by Google which has been the overwhelming beneficiary of the content we have put online. A postmodern PayPal springs up to make this distribution system easy.

Thirty of our 100 kids are now accumulating value. The best of them are accumulating quite a lot of value. Let’s suppose that a piece of fan art, drafting on the success of a hit TV show, goes viral. Let’s say it is viewed by an audience of 100,000 people, twenty percent of whom tip 40 cents on average. The result, eight thousand dollars, is not a prince’s ransom. (I would check these numbers. An anthropologist with a calculator is a dangerous thing.) And if it is used to allow someone to move out of their parent’s basement, it has no obvious cultural effect.

But if our winner uses the money to take the summer off from her job at McDonald’s, this is a difference from which real differences can spring. Now a good artist can become a more productive artist and eventually a better artist. And a virtuous cycle is set in train. More and better work brings in more income, more income becomes more time free for work, and this leads to more improvements in art and income. Eventually, the McDonald’s job can be given up altogether.

In this scenario, the gift economy loses…but culture wins. The supply of good work increases. Standards rise. Good artists get better.

I expect this vista will make Clay Shirky’s eyes water and possibly tear. (My text is Shirky’s Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age.) He might well feel this is a brutal intrusion of capital into a magical world of generosity. Well, not so fast. In point of fact, the internet as a gift economy is an illusion. This domain is not funding itself. It is smuggling in the resources that sustain it, and to the extent that Shirky’s account helps conceal this market economy, he’s a smuggler too. This world cannot sustain itself without subventions. And to this extent it’s a lie.

Shirky insists that generalized reciprocity is the preferred modality. But is it?

[In the world of fan fic, there] is a “two worlds” view of creative acts. The world of money, where [established author, J.K.] Rowling lives, is the one where creators are paid for their work. Fan fiction authors by definition do not inhabit this world, and more important, they rarely aspire to inhabit it. Instead, they often choose to work in the world of affection, where the goal is to be recognized by others for doing something creative within a particular fictional universe. (p. 92)

Good and all, but, again, not quite of this world. A very bad situation, one that punishes creators and our culture, is held up as somehow exemplary. But of course there are reputation economies that spring up, but we don’t have to choose. We can have both market and reputation economies. But it’s wrong surely, to make the latter a substitute for the former.

Shirky appears to be persuaded that it’s “ok” for creators to create without material reward. But I think it’s probably true that they are making the best of a bad situation. Recently, I was doing an interview with a young respondent. We were talking about her blog, a wonderful combination of imagination and mischief. I asked her if she was paid for this work and she said she was not. “Do you think you should be paid?” I asked. She looked at me for a second to make sure I was serious about the question, thought for a moment and then, in a low voice and in a measured somewhat insistent way, said, “Yes, I think I should be paid.” There was something about her tone of voice that said, “Payment is what is supposed to happen when you do work as good as mine.” One data point hardly represents proof of my position. But it does suggest what might happen when the possibility of payment enters the world. A light goes on. The present internet is so much a gift economy and so little a market one, that it is hard for its occupants to imagine alternatives.

I am not going to take up the intrinsic — extensive distinction that matters here. Clearly, people are now being “paid” in intrinsic satisfactions. They are making great work online for the sake of doing so. But I believe it’s true that you don’t need to descend as I do from Scottish Presbyterians to think that here too the intrinsic was never meant to be a substitute for the extrinsic. The luckiest people in the world get paid twice, with intrinsic satisfaction and extrinsic value. That’s actually what we’re hoping for. This is, mark you, the way the academic world mostly works. Surely, it’s wrong and a little odd to celebrate the intrinsic as an alternative to the extrinsic.

But let’s get to the very large elephant in the room. It is the career satisfactions of the so-called Millennial generation. This group has suffered diminished career options. They have been obliged to work as interns, always with the promise that this would prepare them the “real job” to come. But of course the “real job” often never comes. The obligation to work for free online reproduces the obligation of working for free in the world, as if life were one long internship, unbroken and unpaid. After a while it begins to look like one’s lot in life. My research reveals a culture of compliance in which members of this generation agree to agree that their present circumstances are not outrageous. Millennial optimism and good humor endures. (Let’s imagine if someone had tried to pull this on Gen X. Oh, wait, someone did. The reaction was an “alternative” culture and a ferocious repudiation of the status quo.)

But back to our academic contemplation of the gift economy. When Shirky says that work given “freely” on line is a great act of generosity, I think we’re entitled to say that generosity is only properly so-called when there are alternatives. And there aren’t. Forced generosity isn’t generosity.

Still more troubling, the gift economy has a second guilty secret. People can only participate if they have access to resources from outside the digital world. In fact, the moral economy excludes people who do not have wealthy parents, generous scholarships, or rewarding day jobs. If someone is poor, uneducated, and or underemployed, it is hard to participate. So much for generosity and connectivity.

Because the “generosity” view is an idealistic view, it feels somehow above reproach. Clearly for Shirky it is manifestly good. But when people are driven by generosity and rewarded with community, something goes missing. Good artists are denied the resources that would make them better. A generation continues to go underemployed. The next evolutionary moment is lost. A series of social and cultural innovations are not forthcoming. The real generative engine of our culture falls silent.

Some will object that there is an economy online even if financial capital does not circulate. They will say that people are paid in reputation, acknowledgement and thanks. Well, yes. But mostly no. The trouble with “acknowledgement” and “thanks” is that they are both mushy and illiquid. They are impossible to calculate. They cannot be exchanged for anything outside the moral economy. Acknowledgment and thanks are not worth nothing. But they verge on the gratuitous. We can “like” something with nothing more than the energy it takes to move the cursor and click the mouse. This is not quite the same as surrendering a scarce value for which sacrifices have been made. Choice, made carefully, at cost, in hope of gain and at peril of loss, this is the fundamental act of economics. Without it, all we have are bubbles of approbation. Our moral economy isn’t an economy, except in a disappointingly slack metaphorical sense.

Finally, I do not mean to be unpleasant or to indulge ad hominem attack, but I think there is something troubling about a man supported by academic salary, book sales, and speaking engagements telling Millennials how very fine it is that they occupy a gift economy which pays them, usually, nothing at all. I don’t say that Shirky has championed this inequity. But I don’t think it’s wrong to ask him to acknowledge it and to grapple with its implications.

The gift economy of the digital world is a mirage. It looks like a world of plenty. It is said to be a world of generosity. But on finer examination we discover results that are uneven and stunted. Worse, we discover a world where the good work goes without reward. The more gifted producers are denied the resources that would make them still better producers and our culture richer still.

What would people, mostly Millennials, do with small amounts of capital? What enterprises, what innovations would arise? How much culture would be created? I leave for another post the question of how we could install a market economy (or a tipping system) online. And I have to say I find it a little strange we don’t have one already. Surely the next (or the present) Jack Dorsey could invent this system. Surely some brands could treat this as a chance to endear themselves to content creators. Surely, there is an opportunity for Google. If it wants to save itself from the “big business” status now approaching like a freight train, the choice is clear. Create a system that allows us to reward the extraordinary efforts of people now producing some of the best artifacts in contemporary culture.