Mirella Sichirollo Patzer's Blog, page 36

September 11, 2012

Written in Ashes Book Tour

Who burned the Great Library of Alexandria? When the Roman Empire

collapses in the 5th century, the city of Alexandria, Egypt is plagued with

unrest. Paganism is declared punishable by death and the populace splinters in

religious upheaval.

Hannah, a beautiful Jewish shepherd girl is abducted from her home in

the mountains of Sinai and sold as a slave in Alexandria to Alizar, an

alchemist and successful vintner. Her rapturous singing voice destines her to

become the most celebrated bard in the Great Library. Meanwhile, the city’s

bishop, Cyril, rises in power as his priests roam the streets persecuting the

pagans. But while most citizens submit, a small resistance fights for justice.

Hypatia, the library’s charismatic headmistress, summons her allies to protect

the world’s knowledge from the escalating violence.

Risking his life, his family, and his hard-earned fortune, Alizar leads

the conspiracy by secretly copying the library’s treasured manuscripts and

smuggling them to safety. When Hannah becomes the bishop’s target, she is

sequestered across the harbor in the Temple of Isis. But an ancient ceremonial

rite between a monk and priestess inside the Pharos lighthouse ignites a forbidden

passion.

Torn between the men she loves, Hannah must undertake a quest to the

lost oracles of Delfi and Amun-Ra to find the one thing powerful enough to

protect the pagans: The Emerald Tablet. Meanwhile, the Christians siege the

city, exile the Jews, and fight the dwindling pagan resistance as the Great

Library crumbles. But not everything is lost…

Written in the Ashes by K. Hollan Van Zandt is an intriguing read. Elegant

prose lines the pages of this epic novel. The story takes place in 5th

century Alexandria where Greek, Roman, and Egyptian culture converges and

clashes. At the heart of the story is a young shepherd girl named Hannah who is

abducted and sold into slavery. Born with a splendid voice, her singing raises

her from the dark side of slavery and sends her into the Great Library of

Alexandria as a student and performer.

This novel has much going for it. There is fascinating history, an

adventurous quest for a lost tablet, romance, a touch of mystery, myth, and magic,

and some powerful female characters. I enjoyed the elegant prose and the

ability of the author to weave a good tale with plenty of plot twists to keep

the reader interested. At times, the pace did slow a little, likely due to the

amount of detail provided, but the interesting storyline held me and kept me

reading to the end. Hypathia, a true historical figure of the times, plays a role

in the story, as does the lost Great Library of Alexandria, a mystery, which

exists to this day.

I offer high praise to the author

for doing a spectacular job recreating a long lost era with a flair for

intricate details and a rich plot. The story was interesting and I enjoyed the

elements of magic and mysticism woven into the story. The novel is quite

ambitious and therefore required a strong focus and concentration while reading.

There is much taking place and this book will provide hours of entertainment and

a bit of learning about an era long forgotten. Definitely recommended for those

who love ancient eras.

I LOVE COMMENTS

From History and Women

Published on September 11, 2012 14:34

September 10, 2012

An Honourable Estate by Elizabeth Ashworth

I was only two chapters into this novel when I felt compelled to look up the Mab’s Cross connection on which this novel is loosely based.

William Bradshaw, [or Bradshaigh] went off to fight the ‘holy wars’ and was gone for ten years. In his absence, and not knowing whether he was alive or dead, Lady Mabel married a Welsh knight. William, however returned, hunted down the newcomer, and killed him at Newton Park, where supposedly, a red stone still marks the spot of the murder.

William forgave his wife, but her confessor insisted that as a penance for her unintentional bigamy, she should go bare-footed and bare-legged to a cross near Wigan from her home, the Haigh, once every week, as long as she lived, to weep and pray for pardon. The cross to this day is called Mab's Cross.

Elizabeth Ashworth’s novel follows more closely the story of William Bradshaw’s involvement in the Banastre Rebellion and begins during the disastrously wet summer of 1315, while the country is still suffering the after effects of Bannockburn the year before.

With crops rotting in the fields and many animals struck down with disease, the country was in the grip of widespread famine, where the price of food was crippling, but the corrupt tax collectors persisted in fleecing the landowners.

Adam Banastre, a minor Lancastrian lord, organises a rebellion against his overlord, Robert Holland, who was secretary to Thomas, Earl of Lancaster. Armed with written approval from their king, Adam and William join this rebellion, which takes the form of a raiding party across Lancashire where they seized food and livestock. Edmund de Neville, the Deputy Sheriff of Lancashire, and Sir Robert de Holland defeated the rebels at Deepdale in Preston. William flees into the hills where he has no choice but to live as an outlaw.

Lady Mabel, waits for news at home in Haigh Hall with her two daughters, but when William’s beloved and injured horse finds its way home, Mabel doubts her husband is still alive. No word comes in the days that follow and with her daughters growing weaker every day, she is close to despair. Then King Edward II seizes the lands passed down to her from her father’s family for a year and a day. Faced with destitution as well as starvation, Mabel has to make a decision which will either save her and her daughters, or mean possible death for them all.

The story is a combination of the legend of Mab’s Cross and the known facts of the Banastre Rebellion, and is handled beautifully by Ms Ashworth. For Medieval times when everything happened slowly, this story is well-paced and Lady Mabel’s conflict is clear and the odious Sir Peter Lymsey is a worthy antagonist.

As her life deteriorates, does Mabel remain romantically loyal to a man she loves but may be dead? Or take the path to preserve her remaining family? Inevitably, whatever choice she makes, Mabel will have to pay the price in the end.

This is not a romantic tale of chivalrous knights and ladies in wimples sewing by a roaring fire. Lady Mabel is vulnerable, powerless, and has to find a way to placate her enemies, keep her tenants from being harassed by a new overlord and her daughters safe and fed. This is about a country in the grip of famine, greed and the ambitions of others in a stark landscape that kept me turning the pages of this well-crafted story.

I LOVE COMMENTS

From History and Women

From History and Women

Published on September 10, 2012 01:00

September 6, 2012

Augusta Ada Byron - The Countess of Lovelace

An Important Woman in Academic History

The Founder of Scientific

Computing

Ada Lovelace

For most of us in today's society, when we think

about computer science and computer programming, we think of self-proclaimed

nerds sitting at computer screens and college prodigies creating billion dollar

websites in their dorm rooms (Facebook?)—and almost all of these images brought

to mind are male. Today, the majority of student majoring in computer science

and professionals working as computer programmers are male. However, interestingly,

the history of the now booming industry of computer programming and scientific

computing was actually founded by a woman.

Ada Lovelace

Augusta Ada Byron, Countess of Lovelace, now

most commonly known as Ada Lovelace, born in 1815, was an English mathematician

and writer and is noted as the world's first computer programmer. However, for

the most part, this recognition is only really known by those close to the

academic study of computer science. For the general public, Ada might be better

known for being the first daughter of famous English poet Lord Byron. Ada had

no relationship with her poet father, moving away from him with her mother when

she was just a girl. Aside from her interesting heritage, Ada's academic resume

and history is quite remarkable.

Mary Somerville

In her adult years, Ada became close friends

with Mary Somerville, a noted researcher and scientific author in the 19th

century. Somerville introduced Ada to Charles Babbage who would soon become her

mentor and academic inspiration. Babbage was a mathematician, philosopher,

inventor, and mechanical engineer who was working on the concept of a

programmable computer when Ada met him.

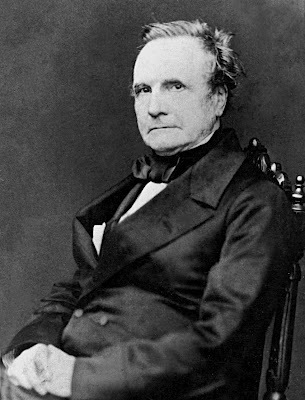

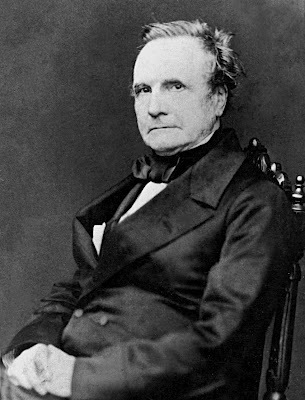

Charles Babbage

Ada's work on what would eventually be

the first computer program began with the nine-month process of translating

Italian mathematician Luigi Menabrea's memoir on Babbage's newest proposed

machine, the Analytical Engine.

Luigi Federico Menebrea

Ada made this transition and added several

notes of her own to the work. Explaining Babbage's Analytical Engine was no

simple task—many had tried and failed. Ada, however, prevailed and added a

section that included in great detail a method for calculating a sequence of

numbers with the Engine. This calculation (or program) would have run correctly

had the Analytical Engine been built at the time. The actual machine based off

of Babbage's work was not completed until 2002.

Ada Lovelace

Ada's work was well received and she was highly

regarded among academics and scientists of the time as a strong writer and

talented mathematician. Her work on the Analytical Engine and her method of

calculation, however, would not be formally recognized as the first computer

program ever written until much later over 100 years after her death. With the

current atmosphere that surrounds science and computer programming, it is

extremely interesting and valuable to recognize that Ada, a woman, was the

first individual to conjure an algorithm intended for a computer. With STEM

outreach at an educational level and a looming lack of women in the

professional science field, there's something to be said about woman playing a

more prominent role in computer science during the patriarchal days of the 19th

century.

Lauren Bailey is a freelance blogger for www.bestcollegesonline.com. She

loves writing about education, new technology, lifestyle and health. As an

education writer, she works to provide helpful information on the best online

colleges and courses and welcomes comments and questions via email at blauren

99 @gmail.com.

I LOVE COMMENTS

From History and Women

The Founder of Scientific

Computing

Ada Lovelace

For most of us in today's society, when we think

about computer science and computer programming, we think of self-proclaimed

nerds sitting at computer screens and college prodigies creating billion dollar

websites in their dorm rooms (Facebook?)—and almost all of these images brought

to mind are male. Today, the majority of student majoring in computer science

and professionals working as computer programmers are male. However, interestingly,

the history of the now booming industry of computer programming and scientific

computing was actually founded by a woman.

Ada Lovelace

Augusta Ada Byron, Countess of Lovelace, now

most commonly known as Ada Lovelace, born in 1815, was an English mathematician

and writer and is noted as the world's first computer programmer. However, for

the most part, this recognition is only really known by those close to the

academic study of computer science. For the general public, Ada might be better

known for being the first daughter of famous English poet Lord Byron. Ada had

no relationship with her poet father, moving away from him with her mother when

she was just a girl. Aside from her interesting heritage, Ada's academic resume

and history is quite remarkable.

Mary Somerville

In her adult years, Ada became close friends

with Mary Somerville, a noted researcher and scientific author in the 19th

century. Somerville introduced Ada to Charles Babbage who would soon become her

mentor and academic inspiration. Babbage was a mathematician, philosopher,

inventor, and mechanical engineer who was working on the concept of a

programmable computer when Ada met him.

Charles Babbage

Ada's work on what would eventually be

the first computer program began with the nine-month process of translating

Italian mathematician Luigi Menabrea's memoir on Babbage's newest proposed

machine, the Analytical Engine.

Luigi Federico Menebrea

Ada made this transition and added several

notes of her own to the work. Explaining Babbage's Analytical Engine was no

simple task—many had tried and failed. Ada, however, prevailed and added a

section that included in great detail a method for calculating a sequence of

numbers with the Engine. This calculation (or program) would have run correctly

had the Analytical Engine been built at the time. The actual machine based off

of Babbage's work was not completed until 2002.

Ada Lovelace

Ada's work was well received and she was highly

regarded among academics and scientists of the time as a strong writer and

talented mathematician. Her work on the Analytical Engine and her method of

calculation, however, would not be formally recognized as the first computer

program ever written until much later over 100 years after her death. With the

current atmosphere that surrounds science and computer programming, it is

extremely interesting and valuable to recognize that Ada, a woman, was the

first individual to conjure an algorithm intended for a computer. With STEM

outreach at an educational level and a looming lack of women in the

professional science field, there's something to be said about woman playing a

more prominent role in computer science during the patriarchal days of the 19th

century.

Lauren Bailey is a freelance blogger for www.bestcollegesonline.com. She

loves writing about education, new technology, lifestyle and health. As an

education writer, she works to provide helpful information on the best online

colleges and courses and welcomes comments and questions via email at blauren

99 @gmail.com.

I LOVE COMMENTS

From History and Women

Published on September 06, 2012 09:25

August 28, 2012

The Kingmaker's Daughter by Philippa Gregory

Spies, poison, and curses surround her…. Is there anyone she can trust?

In The Kingmaker’s Daughter, #1 New York Times bestselling author Philippa Gregory presents a novel of conspiracy and a fight to the death for love and power at the court of Edward IV of England.

The Kingmaker’s Daughter is the gripping story of the daughters of the man known as the “Kingmaker,” Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick: the most powerful magnate in fifteenth-century England. Without a son and heir, he uses his daughters Anne and Isabel as pawns in his political games, and they grow up to be influential players in their own right. In this novel, her first sister story since The Other Boleyn Girl, Philippa Gregory explores the lives of two fascinating young women.

At the court of Edward IV and his beautiful queen, Elizabeth Woodville, Anne grows from a delightful child to become ever more fearful and desperate when her father makes war on his former friends. Married at age fourteen, she is soon left widowed and fatherless, her mother in sanctuary and her sister married to the enemy. Anne manages her own escape by marrying Richard, Duke of Gloucester, but her choice will set her on a collision course with the overwhelming power of the royal family and will cost the lives of those she loves most in the world, including her precious only son, Prince Edward. Ultimately, the kingmaker’s daughter will achieve her father’s greatest ambition.

Review:

Anne Neville

Anne Neville was a lesser known noblewoman and queen of England. In The Kingmaker’s Daughter, Philippa Gregory brings Anne to vibrant life by writing about her difficult life and subsequent rise to glory as Queen of England. What is most heart-wrenching about Anne’s story is that she and her sister, Isabel, were pawns to the men in their lives whose quest for power was relentless.

Although Anne is not the spirited, feisty heroine of other historical biographical novels, she is truly fascinating. It is important that these women’s lives are written about, not only to show the extent of their suffering at the hands of the men surrounding them, but to clearly reflect the true status of women and their lack of rights in all eras of history. What is important is that Philippa Gregory has written a true and accurate accounting of this woman’s life, and that is what I applaud highly. Her conflict with Elizabeth Woodville is deep and all encompassing throughout the novel and makes for a fascinating story-line.

Although Anne is not the fiery heroine, the conflict surrounding her is all consuming and makes for fast page-turning. The novel captures the reader’s interest from the very first to the very last page. It is eloquently written with believable characters, an incredible amount of brilliant descriptions, and wonderful emotion.

The Kingmaker’s Daughter is the fourth book in a series about the women in Cousin’s War Series - Elizabeth Woodville, Margaret Beaufort, and Jacquetta Woodville. It is not necessary to read this in any particular order. It is fascinating to see how the author moves between these characters, fairly depicting them and their personalities, despite their faults. Fans of Philippa Gregory will definitely enjoy this novel set in a disorderly and dangerous period in England’s rich history. I highly recommend this! What a wonderful story!

I LOVE COMMENTS

From History and Women

Published on August 28, 2012 08:21

August 26, 2012

The Second Empress by Michelle Moran

Book Description:

National bestselling author Michelle Moran returns to Paris, this time under the rule of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte as he casts aside his beautiful wife to marry a Hapsburg princess he hopes will bear him a royal heir

After the bloody French Revolution, Emperor Napoleon’s power is absolute. When Marie-Louise, the eighteen year old daughter of the King of Austria, is told that the Emperor has demanded her hand in marriage, her father presents her with a terrible choice: marry the cruel, capricious Napoleon, leaving the man she loves and her home forever, or say no, and plunge her country into war.

Marie-Louise knows what she must do, and she travels to France, determined to be a good wife despite Napoleon’s reputation. But lavish parties greet her in Paris, and at the extravagant French court, she finds many rivals for her husband’s affection, including Napoleon’s first wife, Joséphine, and his sister Pauline, the only woman as ambitious as the emperor himself. Beloved by some and infamous to many, Pauline is fiercely loyal to her brother. She is also convinced that Napoleon is destined to become the modern Pharaoh of Egypt. Indeed, her greatest hope is to rule alongside him as his queen—a brother-sister marriage just as the ancient Egyptian royals practiced. Determined to see this dream come to pass, Pauline embarks on a campaign to undermine the new empress and convince Napoleon to divorce Marie-Louise.

As Pauline’s insightful Haitian servant, Paul, watches these two women clash, he is torn between his love for Pauline and his sympathy for Marie-Louise. But there are greater concerns than Pauline’s jealousy plaguing the court of France. While Napoleon becomes increasingly desperate for an heir, the empire’s peace looks increasingly unstable. When war once again sweeps the continent and bloodshed threatens Marie-Louise’s family in Austria, the second Empress is forced to make choices that will determine her place in history—and change the course of her life.

Based on primary resources from the time, The Second Empress takes readers back to Napoleon’s empire, where royals and servants alike live at the whim of one man, and two women vie to change their destinies.

Book Review:

Napoleon Bonaparte gained fame for rising from the dregs of poverty to conquer most of Europe in the late 18th to early 19th century.

Napoleon Bonaparte

To do so, in addition to fighting many successful campaigns, he married family members to prominent members of his family to European nobility. Napoleon loved and married Josephine, but after several years of not being able to have children with her, he dissolves his marriage to her, allowing her to keep the title of Empress.

Josephine

This made him free to marry Marie-Louise of Austria. This novel focuses on this second marriage and the final days of his empires as his power diminishes and he loses his grip on the empire he controlled.

Marie Louise

The novel is written in the points of view of Marie-Louise, Pauline Bonaparte Borghese, and Paul - Pauline's Haitian servant.

Pauline Bonaparte Borghese

At the heart of the story is the animosity between Marie-Louise and her husband's sister, Pauline, adding interest and conflict. Paul is a charismatic character who loves and is loyal to his mistress. Throughout, he provides readers with a "sensible" view as the conflicts abounds.

To write a novel in this era is a definite challenge. There are numerous characters, political machinations, and nobles from various countries. After having read the novel about Pauline's life by her descendent, Prince Lorenzo Borghese, I'm not certain Pauline was depicted accurately in Michelle Moran's novel. I didn't find it believable that she would desire to marry her own brother, Napoleon, in order to rule the world. There are a few other small details of historical inaccuracy those familiar with the era may identify. However, this is historical fiction and for those more interested in reading a good story rather dwelling in historical fact, the book is an entertaining and compelling read. Michelle Moran's interpretation of the characters provides a different slant and the conflicts between them makes for an interesting read.

I LOVE COMMENTS

From History and Women

Published on August 26, 2012 09:20

August 25, 2012

Women Who Ruled: Shajar al-Durr of Egypt

By: Lisa J. Yarde

Mameluke Soldier

On May 2, 1250 AD, the Mameluke slave-soldiers of Egypt

declared the widow Shajar al-Durr as their ruler. When the Abbasid Caliph of

Baghdad al-Musta'sim heard the news, he expressed the religious view, "Unhappy

is the nation which is governed by a woman." He also suggested that if

the Mameluke warriors had no men to lead them, he would

happily provide acceptable candidates. Shajar's rise to power is even

more remarkable because of her humble origin and status. How did an enslaved

woman from the Eurasian steppes become ruler of an Islamic state in the

medieval period, when her counterparts remained confined traditionally to the

harem?

More than a decade before her ascendancy, the woman who became

Shajar al-Durr, or Spray of Pearls, joined the retinue of slaves in

the service of her future husband, as-Salih Ayyub. One of Saladin's

great-nephews, as-Salih Ayyub chose Shajar as his favorite concubine. The death

of as-Salih's father in 1238 threw Egypt into turmoil, as his sons and

relatives battled for control of the region, a vital part of the Abbasid Empire

that stretched from North Africa to Iraq. The conflict abated in

1240, when Shajar shared her husband's imprisonment. During

their confinement, she gave birth to a son Khalil,

who unfortunately lived for only three months. After her husband's

release and his rise to power in Egypt, he gave Shajar authority to act in his

stead whenever he was away from Egypt on various campaigns that consolidated

his power. He delegated his power to her as Umm Khalil, the mother

of his deceased son, and she held an official seal with that title.

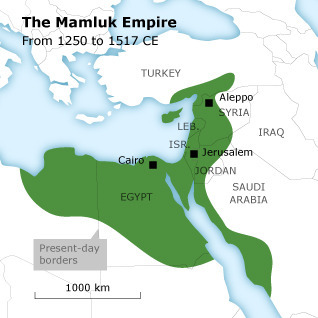

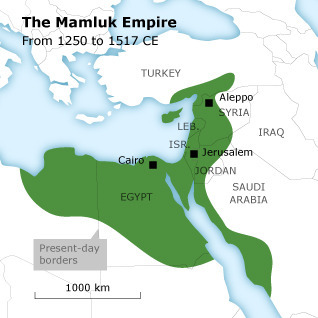

The Mameluke Empire

In July 1429, as part of the Seventh Crusade, King Louis

IX of France landed at Damietta on the Nile. Within five months, his army

marched toward Cairo. Shajar returned with her husband from a campaign against

one of his uncles. The ruler of Egypt faced a precarious situation; the

Crusader army had landed on his shores while he endured a painful infection in

his leg that became abscessed. He suffered an amputation, but within days

left Shajar a widow. She acted decisively, by secretly sending word to Turan

Shah, her husband's son by another woman and having her husband's servants

go about their normal routines, including bringing meals to his tent. Later,

Turan Shah defeated the Crusaders at the Battle of al-Mansurah. Turan became ruler

of Egypt in February 1250. He didn't endear himself by drinking alcohol against

religious proscriptions, or by removing his father and Shajar's confidantes

from positions of power and replacing them with his own men.

The Mameluke soldiers assassinated Turan three months later with

Shajar's blessing.

Coinage minted in Shajar al-Durr's name

She had ruled Egypt in her husband's absence and would do so

again. Among her titles, she became Queen of the Muslims. Friday prayers

in the mosques mentioned her by name and she had coins minted with her titles.

Yet, she could not perform the traditional tasks a new Islamic ruler

would have completed, including the reception for princes and judiciary in

which she would have accepted their personal oaths of loyalty, or the

traditional procession of a new monarch through the streets of Cairo. After the

Caliph's stinging rejection, the Mameluke government tried another

solution. In August 1250, they suggested a marriage between Shajar

and Aybak, the commander-in-chief of her army. Although he reigned with her,

she never truly ceded power to her new husband. She made him divorce his

first wife. Coins of the kingdom now bore both their names and all

official documents required both their signatures. He even needed her

permission before coming into her presence.

Shajar al-Durr's tomb

In April 1257, Shajar decided to move against Aybak. Not only had

her government forced her to share power with him, but she also learned he

intended to marry another woman. She arranged for his murder while he took a

bath and later, feigned ignorance about his fate. Aybak's men did

not believe her. They delivered her to the first wife of Aybak and

her servants, who beat Shajar to death with wooden clogs and threw her body

outside the palace. Her body remained in a ditch, defiled for several days

until her interment.

For just 80 days, Shajar had ruled the Islamic state of Egypt

without relying on the power her husband held. Ultimately, the traditional

expectations of women and her own miscalculations about the exercise of power

brought about her ruin.

I LOVE COMMENTS

From History and Women

Mameluke Soldier

On May 2, 1250 AD, the Mameluke slave-soldiers of Egypt

declared the widow Shajar al-Durr as their ruler. When the Abbasid Caliph of

Baghdad al-Musta'sim heard the news, he expressed the religious view, "Unhappy

is the nation which is governed by a woman." He also suggested that if

the Mameluke warriors had no men to lead them, he would

happily provide acceptable candidates. Shajar's rise to power is even

more remarkable because of her humble origin and status. How did an enslaved

woman from the Eurasian steppes become ruler of an Islamic state in the

medieval period, when her counterparts remained confined traditionally to the

harem?

More than a decade before her ascendancy, the woman who became

Shajar al-Durr, or Spray of Pearls, joined the retinue of slaves in

the service of her future husband, as-Salih Ayyub. One of Saladin's

great-nephews, as-Salih Ayyub chose Shajar as his favorite concubine. The death

of as-Salih's father in 1238 threw Egypt into turmoil, as his sons and

relatives battled for control of the region, a vital part of the Abbasid Empire

that stretched from North Africa to Iraq. The conflict abated in

1240, when Shajar shared her husband's imprisonment. During

their confinement, she gave birth to a son Khalil,

who unfortunately lived for only three months. After her husband's

release and his rise to power in Egypt, he gave Shajar authority to act in his

stead whenever he was away from Egypt on various campaigns that consolidated

his power. He delegated his power to her as Umm Khalil, the mother

of his deceased son, and she held an official seal with that title.

The Mameluke Empire

In July 1429, as part of the Seventh Crusade, King Louis

IX of France landed at Damietta on the Nile. Within five months, his army

marched toward Cairo. Shajar returned with her husband from a campaign against

one of his uncles. The ruler of Egypt faced a precarious situation; the

Crusader army had landed on his shores while he endured a painful infection in

his leg that became abscessed. He suffered an amputation, but within days

left Shajar a widow. She acted decisively, by secretly sending word to Turan

Shah, her husband's son by another woman and having her husband's servants

go about their normal routines, including bringing meals to his tent. Later,

Turan Shah defeated the Crusaders at the Battle of al-Mansurah. Turan became ruler

of Egypt in February 1250. He didn't endear himself by drinking alcohol against

religious proscriptions, or by removing his father and Shajar's confidantes

from positions of power and replacing them with his own men.

The Mameluke soldiers assassinated Turan three months later with

Shajar's blessing.

Coinage minted in Shajar al-Durr's name

She had ruled Egypt in her husband's absence and would do so

again. Among her titles, she became Queen of the Muslims. Friday prayers

in the mosques mentioned her by name and she had coins minted with her titles.

Yet, she could not perform the traditional tasks a new Islamic ruler

would have completed, including the reception for princes and judiciary in

which she would have accepted their personal oaths of loyalty, or the

traditional procession of a new monarch through the streets of Cairo. After the

Caliph's stinging rejection, the Mameluke government tried another

solution. In August 1250, they suggested a marriage between Shajar

and Aybak, the commander-in-chief of her army. Although he reigned with her,

she never truly ceded power to her new husband. She made him divorce his

first wife. Coins of the kingdom now bore both their names and all

official documents required both their signatures. He even needed her

permission before coming into her presence.

Shajar al-Durr's tomb

In April 1257, Shajar decided to move against Aybak. Not only had

her government forced her to share power with him, but she also learned he

intended to marry another woman. She arranged for his murder while he took a

bath and later, feigned ignorance about his fate. Aybak's men did

not believe her. They delivered her to the first wife of Aybak and

her servants, who beat Shajar to death with wooden clogs and threw her body

outside the palace. Her body remained in a ditch, defiled for several days

until her interment.

For just 80 days, Shajar had ruled the Islamic state of Egypt

without relying on the power her husband held. Ultimately, the traditional

expectations of women and her own miscalculations about the exercise of power

brought about her ruin.

I LOVE COMMENTS

From History and Women

Published on August 25, 2012 06:39

August 24, 2012

The Second Empress by Michelle Moran

The Second Empress is set in the final years of Napoleon's reign, when at 40, he divorces the allegedly unfaithful Josephine and take the 19 year-old Maria-Lucia of Austria as his wife to provide him with a male heir. Napoleon’s sister, Pauline, is a driven, outrageous character who, having just rid herself of Josephine, now has to contend with an Austrian princess who didn’t obtain her title by inventing it. Pauline is furious and believes she should to rule Napoleon's empire jointly with her brother like the ancient Egyptians.

The reader is left in no doubt that Maria-Lucia is to be sacrificed to save her country and Napoleon’s ambition for a legitimate heir – no pressure there then for the poor girl!

Marie-Louise accepts her fate with the dignity of a Hapsburg Princess raised to a life of duty, while Napoleon, a military genius but completely inept when it comes to relationships, seems to think this pretty teenager will be overawed and honoured to be shackled to a podgy, balding middle-age-man [that is-by early 19th century standards].

Marie Louise is in love with Adam Neipperg, an Austrian Count who is her lover, and is heartbroken to leave him behind, but he and her father promise to come for her. When is not specified, but the implication is that once she has given Napoleon a son, this may be achieved. Pauline is certainly determined that is the way things will go.

Marie Louise has little to say to her new husband, or at least nothing she hasn’t been coached to say to maintain the man’s fragile ego – she strikes up a friendship with Hortense, Josephine's daughter, who is now free to leave her husband, Napoleon's brother. However she has also been made Mistress of The Robes to the new empress, a cruel decree of her stepfather’s, which makes Marie Louise’s life slightly more bearable, but she still has to contend with the jealous Pauline.

After Napoleon's defeat in Russia, when he is banished to the island of Elba, Marie-Louise is free of him, but when he escapes, she is not sure what this will mean for her own future.

I really enjoyed reading this story, it’s one of those novels where I couldn't wait for a quiet hour so I could read what happens next. What will the vicious Pauline do to embarrass Marie-Louise and will Queen Caroline show herself up as a Corsican peasant beneath all her furs? The story doesn’t get bogged down with military manoeuvrings, territorial claims or battles either, all of which tend to happen in the background, but concentrates on the dynamics of Napoleon’s court and the women who vie for his attention.

Sumptuous gowns, jewels and pretty women proliferate, [Napoleon doesn't like them plump or tall] which tallies with the early nineteenth century belief that females were considered weak minded, and only capable of functioning as ornamental consorts for their husbands. When Marie-Louise is told she is to marry Napoleon, the greasy Prince Metternich says she'll have more furs and jewellery than any ruler in Europe – as if bling made up for a lack of breeding.

The novel is written throughout in first person, through the alternating points of view of Maria-Lucia, Pauline, and Pauline's Haitian chamberlain, Paul. I found this distracting at first, as once or twice it is not explained whose PoV we were in, so could be confusing, but give a different perspective of the characters.

The beginning chapters concentrate on Marie-Louise’s days as a newlywed, then jump years so the reader tends to see only windows of certain events, but all the characters are very well developed. Although the immoral, and outrageous Pauline is not a pleasant character, I couldn’t help admiring her ruthless determination to have her way, and the depths she was willing to plunge to to obtain it, while being aware of, but secretive about, her own declining health.

I’m English, so for Napoleon to be portrayed as a callous megalomaniac whom absolute power has corrupted absolutely – a man who strives to be more royal than the royals by sheer pomp and extravagance and who rules by fear; which was what I was taught about him in school and I’m not willing to change my opinion now!

This is a fascinating, well-crafted and enjoyable novel which gives a different perspective on Napoleon’s later years. One fascinating point was that Napoleon monitored every sous spent at court, right down to what everyone wore. If a lady wore the same gown twice to a court occasion, she was never to be invited again.

I LOVE COMMENTS

From History and Women

Published on August 24, 2012 01:00

August 13, 2012

Fanny Burney - A Biography by Laurie Graham

FANNY BURNEY: A QUIET HEROINE

By Laurie Graham

Author of A Humble Companion

Laurie Graham Blog

Fanny Burney was a faint literary figure to me until I began doing research for my novel A Humble Companion. The position she held for a short time in the household of King George III and Queen Charlotte, as Second Keeper of the Robes, made it likely that she would appear in my story. I therefore tried to dig beneath her novels to find out what kind of woman she was. Whether or not I succeeded who can say? All I know is I’ve come to admire her enormously.

We know quite a lot about her childhood because of her famous father. Charles Burney was a well-connected musicologist and composer, a busy, and exacting man. Her mother died when she was ten years old and her father remarried. Fanny was the middle child, regarded as a bit slow and so left to educate herself as best she could. She had the run of her father’s library and seems to have used her time rather well. She also, like so many lonely, marginalised children discovered that weapon of sweet revenge: humour.

She began to write satire.

It’s hard for us to imagine the difficulties a female writer faced in the 18th century. It was hardly considered a respectable profession. Fanny submitted Evelina and had it published without asking her father’s permission. She only told him she was its author after he’d conceded it was pretty good. Samuel Johnson thought so too and encouraged Mrs Thrale to take her up. So Fanny’s career as a novelist was launched, but it was far from plain sailing. She earned very little and so, in her mid-30s and still unmarried, when she was offered £200 a year to work for the Queen she felt obliged to accept. This put an end to her novel-writing for a while, but fortunately for us she still kept her delicious diary. I consulted it often when I was writing about the royal household.

The rest of her life was a mixture of happiness and misfortune. She eventually, and against her father’s wishes, married a penniless Frenchman, Alexandre d’Arblay, an exile from the Revolution. Defying her father was another display of her strength of character, and not her last. She had a son, wrote another novel which earned her enough to buy a small house, and then went to France to help her husband try to regain some of his family’s forfeited assets. They were there in 1801 when war broke out again, cut off from England until the end of hostilities. It was in France that she underwent and chronicled her famous account of a mastectomy performed without the benefit of real anaesthesia. If you read nothing else of hers, read that.

Fanny Burney survived to be a grand old lady of 88, still a gifted mimic of the famous people she’d known. She outlived her husband, her son and her sisters. I love her wit, so gentle, with occasional devastating skewering. Jane Austen was influenced by her and so was William Thackeray, and what greater tribute could there be than that?

©LAURIE GRAHAM 2012

A Humble Companion, Quercus Books 2012

I LOVE COMMENTS

From History and Women

Published on August 13, 2012 08:57

August 10, 2012

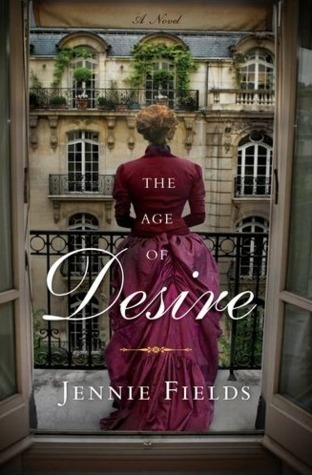

The Age of Desire by Jennie Fields

The scandalous life of author Edith Wharton!

Book Description:

They say behind every great man is a woman. Behind Edith Wharton, there

was Anna Bahlmann—her governess turned literary secretary, and her mothering,

nurturing friend.

When at the age of forty-five, Edith falls passionately in love with a dashing

younger journalist, Morton Fullerton, and is at last opened to the world of the

sensual, it threatens everything certain in her life but especially her abiding

friendship with Anna. As Edith’s marriage crumbles and Anna’s disapproval threatens

to shatter their lifelong bond, the women must face the fragility at the heart

of all friendships.

Told through the points of view of both women, The Age of Desire takes us on a vivid journey through

Wharton’s early Gilded Age world: Paris with its glamorous literary salons and

dark secret cafés, the Whartons’ elegant house in Lenox, Massachusetts, and

Henry James’s manse in Rye, England.

Edith’s real letters and intimate diary entries are woven throughout the

book. The Age of Desire brings

to life one of literature’s most beloved writers, whose own story was as

complex and nuanced as that of any of the heroines she created.

Edith Wharton

My Review:

The Age of Desire is a biographical fiction novel about Pulitzer Prize winning

author, Edith Wharton. The novel delves in the tumultuous and co-dependent

relationship between Edith and her life-long best friend and secretary, Anna

Bahlmann.

Anna Bahlmann is the fair haired lady seated in a chair on the left

At the start of the novel, Edith

is married to Edward (Teddy) Robbins Wharton, a man 12 years her senior, and

who suffered from acute depression that steadily became more debilitating as

their marriage progressed. Their travels ceased and Edith become more and more

disenchanted.

Edith Wharton at her desk

When she meets and falls hopelessly in love with Morton

Fullerton, a notoriously promiscuous journalist who had affairs with both men

and women, an affair of the heart begins.

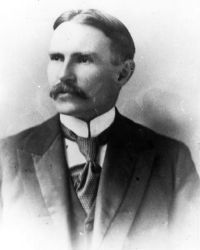

Morton Fullerton

Numerous letters are written between them

throughout their affair. While Edith is consumed with Morton, almost to the

point of abandoning her ailing husband, Anna disapproves and helps care for

poor Teddy who loves his wife. Through time, Morton and Edith’s relationship

deteriorates. The ever-private Edith asks him to burn the letters between them,

but he secretly refuses and publishes them instead.

Edith Wharton's Letters

The Age of Desire opens when

Edith is 45 years of age and portrays the famous author with all her faults. It

reveals her secrets, her scandalous love affair with Morton, and the tumult of

her life despite her success. The illusive relationship with Morton was intriguing,

tempestuous, and hopeless, lending a touch of sadness throughout the novel

because of his aloof attitude towards her. Anna acts as Edith’s conscience. She

disapproves of the love affair with Morton and the neglect of Edith’s husband Teddy.

Despite the animosity between the two women, they need each other, their life-long

friendship linking them.

Edith Wharton at her home

I enjoy books with an edge, and

this book certainly did not disappoint. Realistic, believable, and cut with

minor tragedies and unwise decisions, it is a poignant portrayal of Edith’s

life, loves, and enduring relationships. Fascinating!

I LOVE COMMENTS

From History and Women

Published on August 10, 2012 08:59

Mary Frith 17th Century Highwaywoman

Mary Frith was born to a shoemaker and a housewife in Barbican, Aldersgate

Street near St Paul’s Cathedral in 1584. Mary was ‘tomrig’ or hoyden, wild and

aggressive from an early age. The first record of Frith in trouble with the law

comes when she was indicted in Middlesex for stealing 2s 11d on the 26 August

1600.

Mary had an uncle, her father’s brother, who was a minister. He

attempted to send her to New England in the hope a fresh start would reform her

and took her to a merchant ship lying off Gravesend. However before the ship sailed, Mary jumped

overboard one night and swam to shore, resolving never to go near her uncle

again.

Mary drank in taverns, carried a sword, smoked a long clay pipe and

sometimes dressed as a man. In her 1662 biography The Life and Death of Mrs

Mary Frith, Commonly called Mal Cutpurse; it is claimed Moll was the first

woman in England to smoke. She would also steal purses from passers-by, both

inside and along the approaches to St Paul’s Cathedral, using an accomplice who

distracted the victims’ attention while Mary cut the strings that secured the

leather purses to their belts - a skill that earned her the nickname of’ Moll

Cutpurse’. Her other name was, "The Roaring Girl" taken from roaring

boys; the young gentlemen who caroused in taverns, and then picked brawls on

the street for entertainment.

Mary was indicted in Middlesex on 26th August 1600 for stealing 2s when

she was sixteen and presented herself in public in a doublet and baggy

breeches, smoking a pipe. She also appeared frequently at The Old Bridewell,

the Compters and Newgate for her irregular practices, and burnt in the hand

four times and she is recorded as having been burnt in the hand, a common

punishment for thieves, 4 times.

Her notoriety resulted in two plays being written about her; The Madde

Pranckes of Mery Mall of the Bankside by John Day in 1610, and a year later,

Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker wrote, The Roaring Girl.

Mary often performed in men's clothing at the Fortune Theatre in 1611.

On stage she bantered with the audience and sang songs while playing the lute.

Her habit of wearing men’s clothes resulted her in being cited to appear in the

Court of Arches, where she was sentenced to stand and do penance in a white

sheet at St Paul's Cross during morning sermon on a Sunday. This was hardly a

punishment for an exhibitionist such as Mary Frith, who continued to wear male

clothing, and adorned her house with many mirrors so she might admire herself

in every room.

Women who dressed in men's attire on a regular basis were generally

considered "sexually riotous and uncontrolled", but Mary claimed to

be uninterested in sex.

On 9 February 1612, Mary was required to do a penance for her

"evil living" at St. Paul's Cross. She put on a performance,

apparently weeping bitterly and appeared penitent, but according to observers:

‘She wept bitterly and seemed very penitent, but yt is since doubted

she was maudelin drunck being discovered to have tipled three quarts of a sack

before…’

She married Lewknor Markham (possibly the son of playwright Gervase

Markham) on 23 March 1614. It has been alleged that the marriage was little

more than a charade, contracted to give Frith a counter when suits against her

referred to her as a "spinster". Lewknor probably took a cut of

Mary’s earnings in return for her using his name.

By the 1620’s, Moll lived within two doors of the Globe tavern in Fleet

Street, over against the Conduit, almost facing Shoe Lane and Salisbury Court,

where she turned to fencing. Victims of pickpockets would come first to Moll

and offer her compensation in exchange for the retrieval of their stolen goods.

The thieves, having obtained adequate ransom for their booty, handed them over.

This arrangement kept both sides happy and alleviated the need for ‘the hue and

cry’ as the authorities always knew where to look for stolen property.

As part of the society of ‘divers’, ‘file clyers’, ‘cutpurses’ or

‘pickpockets’, Mary was also a pimp, procuring young women for men, but also

respectable male lovers for middle-class wives. In one case where a wife

confessed on her deathbed to infidelity with lovers provided by Mary, she

convinced the woman's lovers to send money for the maintenance of the children

that were probably theirs.

She also became acquainted with, ‘heavers’, who stole shop books from

drapers and mercers, or other rich traders. These they brought to Moll, who

would offer them back to their owners for a fee.

Showman William Banks bet her £20 that she wouldn’t ride from Charing

Cross to Shoreditch dressed as a man. But she did so in style, flaunting a

banner, blowing a trumpet and causing a riot in the process. Part of the excitement

was due to the fact that the horse she was riding was Morocco, the most famous

performing animal in London. Shod in silver, it could dance, play dice and

count money. Its most famous trick was climbing the hundreds of narrow steps to

the top of old St Paul’s and dancing on the roof.

Contrary to her riotous lifestyle, Mary’s house in Fleet Street was

always immaculate and surprisingly feminine, thanks to three full time maids. She kept parrots and bred mastiffs, pampering her dogs like children.

Each of them slept in their own bed, complete with sheets and blankets and fed

on special food she boiled up herself.

Mary was an ardent Royalist, and was approaching sixty when she turned

highwaywoman during the Civil War. Like her highwaymen friend, Captain James

Hind, gained satisfaction by robbing Parliamentarians, her most memorable

exploit was when she robbed General Sir Thomas Fairfax. She held up his

carriage on Hounslow Heath and relieved him of two hundred and fifty

‘jacobuses’. She shot Fairfax in the arm and then killed two horses of his

escort to prevent pursuit.

She was captured at Turnham Green when her horse went lame and sent to

Newgate, tried and sentenced to death. However, she avoided her date with the

hangman, by paying a 2000 pound bribe, and released on 21 June 1644 from

Bethlem Hospital after being cured of insanity.

The Bethlem Hospital by Hogarth

According to the Newgate Calendar: ‘After seventy four years of age,

Moll being grown crazy in her body, and discontented in mind, she yielded to

the next distemper that approached her, which was the dropsy; a disease which

had such strange and terrible symptoms that she thought she was possessed, and

that the devil had got within her doublet.’

Moll died on 26 July 1659, and in her will she expressed a desire to be

buried 'with her breech upwards, that she might be as preposterous in her death

as she had been all along in her infamous life.'

She was buried in St Bride’s churchyard, Fleet Street, and her marble headstone was inscribed the following epitaph, composed

by John Milton (1608 - 1674), but seven years later it was destroyed in the Great

Fire of London:

Here lies, under this same marble,

Dust, for Time's last sieve to garble;

Dust, to perplex a Sadducee,

Whether it rise a He or She,

Or two in one, a single pair,

Nature's sport, and now her care.

For how she'll clothe it at last day,

Unless she sighs it all away;

Or where she'll place it, none can tell:

Some middle place 'twixt Heaven and Hell

And well 'tis Purgatory's found,

Else she must hide her under ground.

These reliques do deserve the doom,

Of that cheat Mahomet's fine tomb

For no communion she had,

Nor sorted with the good or bad;

That when the world shall be calcin'd,

And the mixd' mass of human kind

Shall sep'rate by that melting fire,

She'll stand alone, and none come nigh her.

Reader, here she lies till then,

When, truly, you'll see her again.

It is often thought that ‘Moll Flanders’ (1721) by Daniel Defoe, was

partly based on the life of Mary Firth, and was Defoe’s attempt to explain

Moll’s lifestyle, thus changing the way in which female crime was regarded and

explained in the eighteenth century.

The account of her life and crimes, with all its 17th Century prejudices towards women printed in The Newgate Calendar is well worth

reading

I LOVE COMMENTS

From History and Women

Published on August 10, 2012 03:00