Bill Walsh's Blog, page 3

June 18, 2013

Publication Day

Finally, the book is out! Look for it at one of the dwindling number of bookstores near you, or follow the links in this sentence to get me a few referral pennies from Amazon.com or All Sides With Ann Fisher."

At 6 p.m., I'll be at an invitation-only $10,000-a-plate dinner at a friend's house in Bexley, Ohio, just outside Columbus. If you'd like an invitation, just ask. (I'm kidding about the $10,000 dinner. It's actually way more expensive. And there's no dinner.)

Tuesday, June 25: At 6 p.m., I'll be at the Book Loft in the lovely German Village section of Columbus, reading and signing.

Thursday, June 27: At 7 p.m., I'll be at Nicola's Books in Ann Arbor, Mich., reading and signing.

Monday, July 1: At 7 p.m., I'll be at Politics & Prose, the premier bookstore in Washington, D.C., reading and signing. I have fond memories of my appearance there for "The Elephants of Style."

Friday, July 5: At 5:15 p.m. Eastern time (4:15 p.m. Central time), I'll be on Wisconsin Public Radio's "Central Time."

May 21, 2013

A U-Turn

With "Yes, I Could Care Less" coming out June 18, I expected to be doing some interviews and getting some attention round about now. And while there have been a few early reviews, some kinder than others, the Bill Walsh project that seems to have taken the world by storm is not my year-or-so-in-the-making, 256-page book, but rather 18 seconds of video captured by the camera that I affixed to my helmet when I was blogging for Bicycling magazine and have kept using while commuting by bike because, well, why not?

Last Thursday, which happened to be the day before the official Bike to Work Day, I was in the bike lane that bisects Pennsylvania Avenue, about halfway to work, when, as happens more often than it should, a cabbie (it's usually a cabbie) decided to make a U-turn across that bike lane. Which is dangerous and illegal. And so I shouted "Illegal!" (I've shouted worse.) And he looked at me and thought about it and ... made the U-turn anyway. And, instantly, I heard a siren. Yes, right behind that cabbie was a police car, and he was being pulled over. It was the FBI Police, as it happens (the District of Columbia has a lot of police forces you've never heard of), but that'll do.

I thought the instant karma was mildly amusing, and so I edited my video and put it on YouTube.

I had no idea. Quickly there were licensing and partnership offers. (I hope I did a good job accepting and declining.) There was coverage. I made Reddit, then Washington City Paper and DCist and Greater Greater Washington and Romenesko and the Orlando Sentinel. Even Kenneth in the 212. And a TV show! Before long there were a million views. A million.

This is just wacky. If a million people know my book exists, I'll be pretty darn lucky.

April 19, 2013

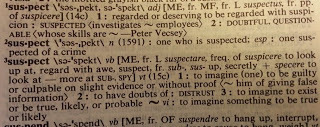

A Suspect Word

Because cops use the word suspect to mean, essentially, subject, and because too many journalists are parrots who just repeat what cops say, too many ordinary people have lost sight of the word's very simple and rather obvious meaning: As a noun in reference to a crime, a suspect is a person suspected of committing that crime. Keep that in mind, write what you know and attribute what you don't, and you'll be fine.

Some examples:

Police are searching for the suspects who robbed an East Side man Friday night. They have no suspects in the case.

Sometimes the parrots make things easy. If there are no suspects, of course, there are no suspects. But the first sentence would be flawed even without the second. Police are searching for the robbers. Or you could say they're searching for suspects in the case. And even if the phrase "the suspects" made sense -- if the police had actually identified suspects in the case but were still searching for them -- you don't know that the suspects are, in fact, the robbers. To write about "the suspects who robbed" would not only violate my "write what you know" guideline but also put you at risk of a libel judgment.

Surveillance video shows two suspects ransacking the store.

The video shows burglars or thieves. Again, if the police don't know who the burglars/thieves are, there are no suspects. If they think they know, you don't know whether they're right. Some reporters and editors shy away from burglar and thief and other perp-nouns because they think they're being super-duper cautious about libel. This is misguided not only epistemologically but also legally: If you go around saying that "suspects" committed crimes, where does that leave you when the word actually means something, when a name is attached? It leaves you as the reporter or editor who may have libeled the person behind that name, that's where.

The Boston Marathon case is interesting and perhaps counterintuitive. Because the photos and video clips released did not conclusively show a crime being committed, the word suspect actually was appropriate for a change in reference to the unnamed and then named men being sought by police. And even if the videos had definitely shown bombers, it would have been inappropriate to use that word to describe the actual men with actual names whom police identified as being the men depicted. Maybe they aren't the same people. So you'd have to use bombers in describing that hypothetical photographic evidence but suspects in describing the named men suspected of being those bombers. Write what you know.

The suspect was described as a white man in his 50s.

Such a sentence would make sense if the police had a specific person in mind and were instructing people to help them find him. Usually, though, there is no suspect -- the killer or rapist or robber or whatever is being described.

Police are confident all the suspects have been arrested.

The problem with this one is a little more subtle. Again, it's about that definite article. If there are, say, three suspects, the police don't need to speculate about their confidence; they know whether all of them have been arrested. The more likely meaning of such a sentence is that the crime was committed by a previously unknown number of people but the police are pretty sure the three guys they hauled in are the three and only three responsible. Police are confident no [insert perp-noun]s in the case remain at large. Police do not think they will be making any more arrests in the case.

Police are seeking a person of interest.

Person of interest. Possible suspect. I've even heard of police suspecting that somebody's a suspect. While it is important to attribute allegations and avoid putting words in authorities' mouths, there will be times when a news outlet has to go beyond weasel words and tell it like it is. Don't say police described someone as a suspect in a case if they didn't, but it might occasionally be appropriate, when the search for a so-called person of interest is clearly a criminal manhunt, to call a suspect a suspect in a lead paragraph or a headline. It's not a legal term. (Though you may want to run my advice by your lawyers; libel could be a concern.)

The confessed killer is scheduled to appear in court Monday.

If you saw the confession yourself, that's probably fine. If not, beware. Don't believe everything the cops tell you. In cases with possible confessions or seemingly obvious guilt, the news media are in a tough spot. You don't want to look foolish treating James Holmes as a random dude picked up by the police on a hunch, but you also don't want to set a precedent of pre-judging criminal cases. Hence, James Holmes remained a "suspect" long after it was obvious he opened fire in that movie theater.

You can read more about the problem of parrots in my new book, "Yes, I Could Care Less," which comes out June 18.

April 9, 2013

When It Pays to Be Pedantic

People write "Illinois senator" when they mean a U.S. senator from Illinois, and I change it, because there are also Illinois senators as in members of the Illinois Senate.

People write "last January" when they mean the last January to have occurred, and I change it, because there's also last January as in January of last year.

People write "Kansas City" when they mean the one in Missouri, and I change it, because there's also the one in Kansas. They write "Fairfax" when they mean giant Fairfax County, Va., and I change it, because there's also tiny Fairfax City, Va., which by a quirk of Virginia law is not part of the county that surrounds it.

I change these things over and over, and every once in a while I wonder why. And it never fails: The minute I'm about to give in, somebody writes "Illinois senator" in reference to a member of the Illinois Senate. Or "last January" in a reference to two Januarys ago. Or "Kansas City" in a reference to Kansas. Or "Fairfax" in a reference to Fairfax City.

And I smile a little smile and wonder what I was thinking and continue being a big, fat pickypants.

I "leave room," a concept I explain further in "Yes, I Could Care Less: How to Be a Language Snob Without Being a Jerk," coming June 18 to a bookstore near you.

March 4, 2013

More Stupid (if Not More-Stupid) Truncations

In "Lapsing Into a Comma," I hmphed about what I called illegal clipping, the too-common habit of oddly and sometimes misleadingly truncating a proper noun. USA Today becomes "USA," Consumer Reports becomes "Consumers," Mount Vernon Square becomes "Mount Vernon." (Oddly, I started my rant with the use of "Van Dorn" to refer to the Van Dorn Street station on the D.C. area's Metro system, which in retrospect doesn't seem that odd at all -- and isn't misleading the way "Mount Vernon" is.)

The list keeps growing. I've been biting my tongue for 15 years while my co-workers referred to Lotus Notes as "Lotus." (If anything, the e-mail program originally produced by Lotus Software is "Notes," the way Microsoft Word is "Word" and not "Microsoft.") Thankfully, the Post just switched from Lotus to Microsoft -- I mean, from Notes to Outlook.

And I was rather surprised to learn that everyone but me refers to the restaurant chain Noodles & Company as "Noodles."

Then there was the cellphone conversation I overheard today, in which a woman was telling her kid's father or nanny or babysitter that it was almost time for "Sesame." Not "Sesame Street" or "The Street" -- "Sesame." Maybe she can get together with the "Noodles" people and do some Chinese cooking.

February 27, 2013

Order Now!

My third book, "Yes, I Could Care Less: How to Be a Language Snob Without Being a Jerk," is now available for pre-order on Amazon.com. Place your order now to ensure it's dispatched to you as soon as the clock strikes June 18 (and also to maybe get that Amazon sales rank above 1,776,740).

November 19, 2012

The Breaks

The following is an outtake from my forthcoming book, "Yes, I Could Care Less: How to Be a Language Snob Without Being a Jerk." My editor considered it too inside-baseball for an audience larger than newspaper copy editors, and she was probably right.

TINY ACTS OF TYPOGRAPHICAL ELEGANCE

In the arcane subculture of the headline writer, there is a concept called the bad break. As with pretty much everything else I’m writing about, those rules have relaxed over the years. There was a time when many newspapers would have rejected the following:

President

heads to

Europe

Are you horrified by that preposition at the end of the second line? Yeah, me neither. But I’m still enough of a traditionalist to consider the following break — leaving a preposition at the end of the first line — undesirable. I don't rule out such breaks, but I try to avoid them.

President heads to

Dominican Republic

Chances are, if you’ve never been initiated into the headline-writing fraternity, you didn’t see an aesthetic problem with that break either. And you’d be onto something. For many years now at the annual conference of the American Copy Editors Society, Alex Cruden, now retired from the copy desk of the Detroit Free Press, has invited civilians into our world and asked them to evaluate headlines. He’s found that they rarely if ever care or even notice how headlines break — and not only in the case of obscure technical violations involving prepositions, conjunctions and articles.

Cruden and others argue that the utter lack of reader awareness of such things is a good reason not to worry about them. That viewpoint has clearly gained traction, even among copy editors who remain largely hidebound when it comes to the dictates of their stylebooks. The following examples come from my own paper, the Washington Post.

N.Y. banker contributed

money, time to cancer

group for young people

Fifteen years after discovering taekwondo at a mall

kiosk, Alexandria’s Jennings is bound for London

Savage gives first crash

course in sex on campus

Whistleblower sues IRS to get reward

Claims disclosures showed how Dutch

bank helped clients avoid paying taxes

Are you horrified? Please be horrified. Sparing readers a preposition at the end of the first line of a headline is a tiny act of elegance that you can take or leave, but — except in narrow one-column headlines, in which all bets are off — readers should not be led to believe even for a nanosecond that a New York banker loves cancer. Dan Savage gave a crash? Oh, a crash course. A Dutch bank is a Dutch bank, not a Dutch ... bank. We can debate just where these examples fall on the continuum from tiny act of elegance to colossal act of courtesy, but line breaks separate; they cause a reader to pause, however briefly. To dismiss the importance of line breaks is to deny poetry.

It’s mainly the poetry — the rhythm — of the headline that I’m talking about here, but occasionally a bad break can be a fatal flaw, changing the message conveyed. A Columbia Journalism Review compilation of humorous headline gaffes includes this one:

Man shot in back,

head found in street

The humorous misreading is still possible with the “back, head” part unbroken, but I think it’s a lot less likely. One of Jay Leno’s headline-mocking books offers a similar example:

Helicopter

powered by

human flies

I’m not sure whether any of Alex Cruden’s people-off-the-street sessions included headlines like those. Obviously, any literate person would notice the humor in those examples as they were published; the question becomes whether they would feel precisely the same way about them laid out like this:

Man shot in back, head found in street

Helicopter powered by human flies

Or this, if you’ll excuse the problem of line lengths (a problem that’s also on our radar):

Man shot in back, head

found in street

Helicopter powered by human

flies

While I consider Cruden’s research admirable and useful, especially when I’m worried about a questionable break and have no time to fix it, I have to raise the question: Is what readers would notice really a valid criterion upon which to base editorial judgment? We spell supersede and stratagem and, heck, judgment the way we do because those are the correct spellings, even though a large majority of readers would never register supercede or strategem or judgement as an error.

Furthermore, I’ve always thought that bad breaks carry a subliminal message of sloppiness. Readers may not think they notice them, but I’d like to see a controlled study in which they’re presented with two otherwise identical pages, one following the old conventions and the other ignoring them. I’d bet my green eyeshade they would rank the former as somehow more polished, more professional, even more credible.

That cumulative effect, I think, holds true for all tiny acts of elegance. A bad break here, a usage not quite finished evolving into universal acceptance there, and the next thing you know, there’s a general aura of sloth.

October 25, 2012

On Victims, Bayonets and Paying Attention

In "The Elephants of Style," I examined a couple of examples of instant historical amnesia -- cases of the news media and the public just not paying enough attention to get a story right even in the first telling. No, George H.W. Bush did not accidentally say "September 7" in a slip of the tongue when he meant to say "December 7." He showed up on Sept. 7 and started talking about it being Pearl Harbor Day. No, the powers that be did not compromise with Tonya Harding in allowing her to skate in the Olympics. They capitulated when she threatened legal action.

Well, we're still not paying attention. Take two examples from the current presidential campaign. Remember when Mitt Romney called 47 percent of the American people "victims"? Yeah, no.

What Romney said in the leaked cellphone video of a speech to wealthy campaign contributors was that the approximately 47 percent of working-age Americans who do not pay federal income tax "believe that they are victims." The implication, of course, is that they are wrong to believe such a thing: Not only did he not call people victims; he said, or at least implied, the exact opposite.

And yet many news organizations focused on people being called victims, and some angry YouTube responses even insisted "I'm not a victim!"

I can see how one might feel belittled at the general aura of being called a victim, had Romney actually done that, but stop and think for a minute: Whatever you think of this line of reasoning, isn't a key component of the argument against Romney, and the Republican Party in general, something along the lines of "I am a victim"? If you lost a big chunk of your retirement savings and you think Wall Street shenanigans were to blame, aren't you saying you were victimized? If you lost your house and you think mortgage-lending high jinks were to blame, aren't you saying you were victimized? If you lost your job and you think outsourcing or profit-chasing or excessive executive compensation was to blame, aren't you saying you were victimized?

Then there were the bayonets.

Whatever you think of President Obama's debate zinger -- "You mention the Navy, for example, and that we have fewer ships than we did in 1916. Well, Governor, we also have fewer horses and bayonets" -- you cannot honestly think you are debunking that remark by pointing out that bayonets still exist, and that the U.S. military still uses them. "Fewer" does not mean "none." Partisan outlets do what partisan outlets do, and I understand that, but even mainstream news organizations seemed to be reacting to something Obama never said.

Now, if indeed the armed forces have more bayonets than they did 96 years ago, as some are reporting, that's a debunking.

April 20, 2012

Hopefully, Everyone Will Do as They See Fit

As I settle back into the real world, scratching at imaginary insects under my skin after four days of the heroin-y warmth of sharing a cocoon with hundreds of my people in New Orleans at the annual conference of the American Copy Editors Society, I'm marveling at the reaction to a small tidbit from the Big Easy. The editors of the Associated Press Stylebook have gotten into the habit of using our little gathering to stage publicity stunts, declaring the electronics-industry space saver "mic" as preferred over the actual word "mike" as the abbreviation for "microphone" one year, and removing the hyphen from "e-mail" another. I was relieved to sit in on the AP guys' session this year and hear nothing of particular import.

Oh, there was that "hopefully" thing. Now it's OK in AP style to use the word to mean "it is to be hoped that," in addition to "in a hopeful manner."

That made news. It made some angry. I say: Much ado about nothing, times two.

In the first place, to the extent that the sentence-adverbial role of "hopefully" was ever an issue, it was an issue not of correctness but of taint. Misguided sticklers have made a fetish out of looking at something like "Hopefully the weather will be nice today" and pretend-interpreting it to mean the weather was experiencing a feeling of hope. Meanwhile, they didn't apply that logic to other adverbs used in precisely the same fashion:

Frankly, she's just not that into you. (Wait, you're being frank -- why are you saying she's being frank?)

Honestly, Joliet is a dump. (Wait, you're being honest -- why are you talking about that city being honest?)

Seriously, he's an idiot. (Wait, you're being serious -- why are you talking about him being serious?)

Mercifully, I had an excuse to leave early. (Wait, you're not being merciful -- why are you talking about being merciful?)

Curiously, the cat didn't show up for dinner. (Wait, you're not talking about a curious cat ...)

In the second place, this just isn't a front-burner issue. AP style is used mainly by news organizations, and news organizations, for the most part, are not supposed to express hope or any other opinions. I suppose the stylebook change loosens the reins on some editorial writers, but other than that, it's an almost entirely inconsequential bit of pandering. I'm not complaining; I'm just shrugging.

The taint issue, however, is interesting, and it has broader implications. Even if you enjoy the subject of style as much as I do, you have to admit that the whole point of style is to be invisible. Get the hell out of the way. Don't distract from the writer's message or detract from the writer's credibility. To that end, we sometimes avoid usages not because there's anything wrong with them, but because a lot of readers think there's something wrong with them. Arnold Zwicky has written for Language Log about this mind-set, which he calls "crazies win." Robert Lane Johnson recently discussed the Economist stylebook's caution against splitting infinitives, a policy he feels duty-bound to enforce even though he disagrees with it. There was predictably Zwickian reaction on Twitter and in blogs from, among others, John McIntyre and Jonathon Owen (Owen had discussed the issue at length months earlier, hence the time-warp link).

The split infinitive is right up there among the most baseless and silly prohibitions in all of misguided-sticklerdom. At the Washington Post, the publication that pays my salary, we split infinitives, letters to the editor be damned. On the other hand, I don't get the sense that we're going to be following AP on "hopefully" (we haven't on "email" or "website" or "mic" either). Judgment calls, all. Do you lowercase "e.e. cummings" because "everybody knows" that was his preference, or do you write "E.E. Cummings" because "everybody" is wrong? You'll get angry letters even when you're indisputably correct. If you're one of those people who think I should have just written "one of those people who thinks," perhaps you're the one of the people who wrote the Post to tell us we were wrong on that point when we most certainly were not. (If you look hard, you'll find examples of that error on more than one of the language-expert blogs I've mentioned above.)

*

On another front in language evolution, you're not likely to see the singular "they" any time soon in the stylebook of the Associated Press or the Washington Post or any other major newspaper. This, too, came up at the ACES conference, in a presentation by Sandra Schaefer of the University of Wisconsin at Oshkosh. I caught only part of her session, having been busy learning whether to use "blow job" or "blowjob," but she made the case that "they" is not only the logical candidate to replace "he or she" as a gender-neutral singular pronoun, but also quite well established as such.

I agree on the former point. On the latter, however, I think the burden of proof is formidable. For now, I feel compelled to keep letting the crazies win. I hope with all my being that the evolution away from "he or she" and the like is swift. I also like "they" without a clear plural antecedent ("Trader Joe's is great -- they have a lot of good cheap wine!").

But large mainstream general-interest publications simply aren't on the cutting edge when it comes to language innovation, nor should they be. You can thank this innate conservatism for the fact that I'm not hotmailing you to let you know that I've gifted you and your empoyes thru some cigarets in the frigidaire.

April 19, 2012

Don't Be a Serial Killer

Newspaper style generally eschews the serial comma. I'm fine with that. Toast, juice, milk and Trix. But sometimes that comma is useful. If I write about a city's departments of housing, parks and recreation and well-being, do I mean there's a department of parks and recreation or a department of recreation and well-being? And what if my series consists of three or four full sentences? For many serial-comma-phobic journalists, the answer to those questions tends to be: Semicolons! Ugly, unwieldy semicolons. Clearly, those journalists did not actually read the stylebook to which they are slavishly devoted. AP specifically says that the serial comma is needed in those cases.

IN A SERIES: Use commas to separate elements in a series, but do not put a comma before the conjunction in a simple series: The flag is red, white and blue. He would nominate Tom, Dick or Harry.

Put a comma before the concluding conjunction in a series, however, if an integral element of the series requires a conjunction: I had orange juice, toast, and ham and eggs for breakfast.

Use a comma also before the concluding conjunction in a complex series of phrases: The main points to consider are whether the athletes are skillful enough to compete, whether they have the stamina to endure the training, and whether they have the proper mental attitude.

So it's The departments of housing, parks and recreation, and well-being, not the departments of housing; parks and recreation; and well-being. Once one of the elements in a series includes a comma, then you want those ugly, unwieldy semicolons: The committees on appropriations; health, education and welfare; and labor.

Bill Walsh's Blog

- Bill Walsh's profile

- 29 followers