Anne M. Chappel's Blog, page 3

January 7, 2015

Memories of the great Dhows of Zanzibar

A great fleet of dhows rode at anchor for 3-4 months of the year in the harbour of Zanzibar in the early 1960s. As a child, I marvelled at them, they were the biggest wooden boats that I had ever seen. We sailed past them with our dingy taking in their strangeness and gazing at their vast solidness in awe. These were vessels of the wild open sea. Festooned with ropes made of sisal, their masts slanted at an angle, they spoke of journeys by men who knew the sea like no others. Sometimes I would see lithe dark sailors shimming up the masts with their bare feet. We always complained about the smell of the dhow fleet. Later I learnt that they used fish oil to season the wood. Aging fish oil is not recommended for its smell. Off the stern of the boat hung a large box, big enough for a person to sit in. It had a hole in the bottom and we knew it was the toilet also called the thunder-box. Strange inscriptions and twirling designs were carved as decorations along the hull and over the stern hung the plain red flag of the Sultans of Zanzibar. On their prow would hang an oculus or talisman. The oculus is the ‘eye’ of the boat and was often in the form of a brightly painted eye, rather like a Cyclops eye from Greece. No human or animal replications were portrayed - as the Koran dictates.I knew that this dhow fleet plied an ancient triangular route, from India to the Arabian Gulfand then on to the East African coast. India was the connection to those fabulous trading countries even further east. From ancient times the monsoon winds had made this route feasible and as boats become more sophisticated its importance grew. The monsoon winds were not reliable further south than Zanzibar and our harbour, tucked into the western coast of the island, was very protected when the northern monsoon was blowing.The Arab dhow captains were superb seamen. In 1939, Australian adventurer, Alan Vickers, travelled on a dhow from Aden to Zanzibar and back. In his book, ‘Sons of Sinbad’ he recounts how he found a nakhoda or captain of a boum dhow and arranged his passage south with the north-east monsoon on a boat called The Triumph of Righteousness. Alan believed he was living through the last days of sail. He tells of the journey and it is a window into the past. With western eyes he found the filth the accumulated on the overcrowded main deck difficult to stomach but recognised that these sailors were tough men:‘the constantly cramped quarters, the crowds, the wretched food, the exposure to the elements, the daylong burning sun, the nightlong heavy dews, if they continued to be disadvantages, were far offset by the interest of being there….’You were always aware of the monsoon in Zanzibar. There was no summer and winter on the islands. It was one monsoon or the other or the time in-between when the rains came. The northern monsoon blows from late November to February and the long rains, or masika, come in March as the winds become variable. If you were a girl child born during the rains, you might be called Masika – born in the time of the rains.April is the start of the south-west monsoon. This wind is more violent during the months of June and July so the boats leave with the first winds or stay to the last weeks of the monsoon. It was hard to get insurance for your boat if you left during June and July when many seasoned dhow captains would stay put in a safe harbour. By late September the winds become variable again and Zanzibar experiences the short rains or vuli. Monsoon is a word that English has copied from Arabic.They were not called the ‘trade winds’ for nothing. Zanzibar was a trading nation, perfectly positioned and blessed with the richness of its spices and the produce of the African hinterland. In the 1800s when Zanzibarwas the centre of a maritime commercial empire, the cargo used to be gold, gum copal, ivory and slaves. In my days it was spices, predominantly cloves, mangrove poles, Persian carpets, dates and dried fish that plied its way to and from Arabia. In the narrow streets of Zanzibar’s Stonetown could be found a cornucopia of riches. Small open fronted shops or dukas were filled with wares from east and west. The shopkeeper sat cross-legged at the shop front on the elevated concrete ledge talking to his neighbours. On the main street were the gold and silver merchants with worked semi-precious stones from Ceylon and India. My father wanted to buy some Persian carpets directly from a dhow captain so he put out the word and a little while after the dhow fleet arrived from the Gulf my mother and he went on board to view the cargo. They discussed the weather and the health of their families until much strong sweet coffee or kahawa had been imbibed and general pleasantries had been exhausted. ‘The red dust of the desert was still in the carpets,’ my father said, ‘each one that they brought up from the hold seemed more beautiful than the one before. It was impossible to choose!’

The dhow fleet were intrinsic to the old Zanzibar, when the Omani Sultans ruled and controlled the east African shores. When Sultan Said bin Sultan of Oman and Muscat had moved his capital to Zanzibarin 1840, he travelled with his fleet of dhows to take possession. His family would rule Zanzibar till 1963 and the revolution that ousted the newly independent Zanzibar. Sultan Jamshid escaped while many other Arab Zanzibaris did not. Survivors tell of how many Arab people were forced to embark on overloaded and under provisioned dhows and sent to sea. The revolutionaries wanted them to go back to Arabia. Some of those dhows did not survive the trip. Recently someone told me of a story he had heard while travelling down the East African coast 50 years ago. The first mate of a large cargo boat woke the captain early one morning and asked him to get to the bridge urgently. ‘Look,’ he said, ‘look at our bow!’ There over the bow was draped a huge sail. Both realised what it was: the tremendous triangular sail of a dhow. ‘Get if off, quickly,’ the captain replied, ‘Throw it away’. The cargo boat had ploughed down a dhow in the night. They did not turn around to see if they could find any survivors clinging to bits of wooden hull. It was just one more hazard of the open sea.Some dhows have been converted to motor and still trade along East Africa. Still trading and still involved in smuggling. But the ancient stories of the dhow captains’ bravery and seamanship are lost to us. The great fleet under sail travels no more. The beauty of the lateen sails on the horizon with the monsoon behind them is now a mirage from history.

Published on January 07, 2015 04:21

December 28, 2014

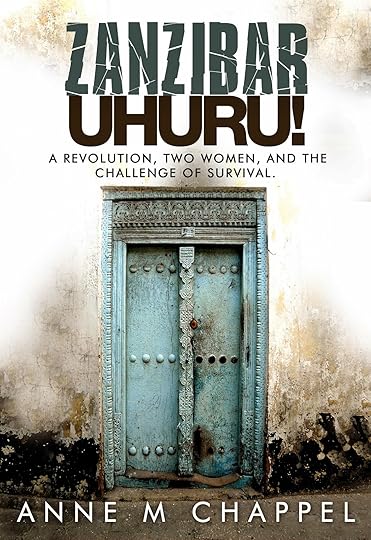

A new novel about Zanzibar starting at the 1964 Revolutio...

A new novel about Zanzibar starting at the 1964 Revolution has been published on Amazon's Kindle and soon to be available as a print edition.http://www.amazon.com/Zanzibar-Uhuru-...

A new novel about Zanzibar starting at the 1964 Revolution has been published on Amazon's Kindle and soon to be available as a print edition.http://www.amazon.com/Zanzibar-Uhuru-...

"It is 1964, a month after independence celebrations in the spice islands of Zanzibar, off the east coast of Africa. A brutal uprising takes place apparently led by a shadowy figure, John Okello. In the capital, Stone Town, a British official, Mark Hamilton, struggles to help the Sultan’s government survive while protecting his young family. In the countryside, Ahmed al-Ibrahim, a Zanzibari Arab father, faces annihilation and a terrible decision. Fatimais his twelve-year-old daughter, and her life is changed forever by the violence that now sweeps across the islands. Fatima’s survival through this chaos and the thirty years of rule by despotic Presidents takes all her courage and the kindness of other families.Elizabeth, Mark Hamilton’s young daughter, also remembers the day of the Revolution and their escape across the seas. Her story too is touched by tragedy. Fatima and Elizabeth are connected in a way that takes almost fifty years to be revealed. Elizabeth will return to Zanzibar to fulfil her father’s final request. The life journeys of the two women are different. The common link is the day of the Revolution and the act of a desperate man."

Published on December 28, 2014 22:00

November 5, 2014

1912 Gandhiji in Zanzibar by Bipin Suchak

The photograph was taken on 27 November 1912 at a function at Victoria Gardens opposite the official residence British Resident.

The photograph shows Gopal Krishna Gokhale in the centre with Gandhiji and Hermann Kallenbach on his right and members of the Karimjee Jivanjee family on his left. My grandfather Mulji Walji Suchak is in the photograph in the third row in the traditional black cap.

Accoording to Gandhiji's autobiography Gokhale came to South Africa in October 1912 and stayed with him for about six weeks and at Gokhle's behest accompanied him to Zanzibar when he sailed for home.

The Indian communities at East African ports along the way saw Gandhiji in traditional Indian clothes for the first time since some twenty years earlier when he wore a turban in a Durban courtroom the day after he first arrived from India, and which he refused to take off - although in the photograph he is wearing a suit.

Gandhiji in his autobiography acknowledged the impact that Gokhale had on him and stated that "Gokhale prepared me for India".

In his book "Gandhi Before India" Ramchandra Guha referring to Gokhale's return to India (page 439) writes:

"En route, they stopped in Zanzibar. The island had an active Indian community, who,it turned out, knew all about the satyagraha in South Africa, and its leader, whose struggle deeply resonated with them. 'Remarkable how the men's faces light up when they hear the name "Gandhi," wrote Kallenbach in his diary, 'and how eager they were to shake his hands' (the footnote here points out to Kallenbach's diary entry for 27 November 1912)

When they parted company in Zanzibar Gakhale told Gandhiji to put South Africa behind him and come home to fulfill his destiny. Gandhiji returned to Indiain January 1915 after having spent nearly 20 years in South Africa. Shortly after his return he was hailed as a "Mahatma"

The rest as they say is history.

Published on November 05, 2014 04:35

August 25, 2014

Tolerance. Principal Foundation of the Cosmopolitan Society of Zanzibar by Mohamed Ahmed Saleh

Tolerance.Principal Foundation of the Cosmopolitan Society of Zanzibar. By Mohamed Ahmed Saleh

For a substantial number of people, notably in the northern hemisphere, the name Zanzibar sounds mythical and makes people dream. However, in reality, it has a physical existence and a particular place in the world map. It is an island country, which consists of Unguja and Pemba islands and a multitude of other islets (approximately fifty). The archipelago has an average area of 2 460 square kilometresThe geographic situation of Zanzibar could be compared with countries and cities such as Hong Kong, Singapore, Shanghai, in South East Asia, Bombay, Cape Town, Aden, Malta, and Gibraltar. These countries and cities, given sound policies, because of their strategic position, always benefit from whatever the prevailing world economic trendA SEAFARING AND MERCHANT PEOPLE Geographically and culturally, Zanzibar belongs to that string of islands which extends all along the east African coast, from Lamu to Comoros, where for many centuries the Swahili culture and civilisation took shape and flourishedAs one of the former important City-States in the Swahili World, Zanzibar’s history was essentially written by the monsoon windsIt was through the interplay of different elements of populations, languages and customs, the mingling of blood and ideas that permeated every aspect of life that led to the development of Zanzibari identity and culture. With all its complexities, Zanzibaremerged as one of the major plural societies of East Africa, composed of a large diversity of communities. Despite of socio-economic contradictions prevailing in the society, notably in terms of class and status, Zanzibar remained one of the few plural societies in Africa that have been successful in crystallising various diverse cultural communities into a single all-encompassing culture. Zanzibari culture is representative of a very rich repertoire with a number of compartments within which one can identify different origins in what is now a homogenous Zanzibari Swahili culture. The various Zanzibari communities were further cemented together by their linguistic and religious unity.

Modern Zanzibari identity is primarily based on the Kiswahili language and the culture associated with it. Bantu by its grammatical structure, Kiswahili language has incorporated in its vocabulary more than fifty percent of words of foreign origin, particularly of oriental background

TOLERANCE AS A TRADITIONAL VALUE

Islam is the religion of the majority of Zanzibaris, representing more than 90% of the total population. It is one of the important factors of inter-communal interaction. The majority of Zanzibaris belong to the sunni branch of Islam, and are followers of Imam ShafiiSome Zanzibaris allegorically compare this prevailing situation in Zanzibarwith that of flowers which are varying in colours but in essence do not change their nature, they remain flowers. An important number of Zanzibaris are also active members of Suffi movements, turuq(Islamic Brotherhood), i.e., mystical group or group of ecstatic performance. The two most important groups in Zanzibarare Shadhiliyya Yashrutti and Qadiriyya. The former finds its origins in Palestine while the latter was introduced from Iraq. These religious or mystical orders include men and women, performing their rituals separately, meet for devotional purposes and attend funeral and other rites involving their members. Their rituals consist of invocations and supplications. They invoke the names of God and other supplications, following a particular rhythm with over-breathing and other physical exercises that induce trance and possessionAlthough Islam and the Swahili language constitute the cultural fundament of the islands’ social fabrics, other religions such as Christianity (Catholics as well as protestants), Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Parsee Zoroastrians, as well as languages such as Hindi, Gujareti and Arabic, coexisted peacefully and respectfully. Irrespective of individual confessions, all Zanzibaris have always congregated together in celebrating Prophet Muhammad’s birthday (Maulid)A true Zanzibari has always been a polyglot, with a capacity of communicating at least in three different languages. S/he would naturally be appreciative of a variety of music: african, oriental (arab and indian) or western (jazz and classical). These different influences appear also in the Zanzibari-Swahili music, taarab, which incorporates in its composition a mixture of african, oriental and western melodies. The evolution of Zanzibaris history and culture was very much marked by the liberty of movement of its population and freedom of expression and press. More than 40 newspapers were established in the country since the first newspaper in East Africa, The Gazette, was established in 1892This spirit of tolerance, kuchukuliana, which in Kiswahili means mutual understanding made the Zanzibari society a cultural mosaic, which has always been open towards integrating not only traders but also invaders. Tolerance has always been one of the major components of Zanzibari social and cultural values. This concept has demonstrated in different periods of Zanzibar history its crucial role in the cultural, social and political processes leading towards the definition and the development of Zanzibari identity and nationalism. Tolerance is not only a concept of the Swahili languageKuadhiniwaFirst hair shaving marks the end of the uterine life of the child and provides an opportunity of communion, around a feast, between family members, friends and neighbours. Traditional teachings encourage good neighbourly relationships. Neighbours are considered to be one’s second family. If charity always begins at home, in the traditional teachings it is highly recommended that it should be extended to one’s neighbours. This is why in the occasion of traditional or religious festivities neighbours usually exchange meals. CircumcisionThrough customary rites and moral teachings one is brought up into understanding life in all its complexities and into believing in the universality of human race. Very often moral teachings encourage the society to stretch out their hands and to reach out to other peoples, other races; and to regard one another with the same respect, affection and dignity, for they all belong to the same human race. The Koran (and the Islamic Faith) is very explicit in its social teachings and endows racial as well as cultural diversity with sacred status as a divine creation: “O Mankind, we have created you male and female, and appointed you nations and tribes so that you may know one another” (Koran 49; 13).

Regardless of colour, creed or background, traditional teachings encourage people to judge the other entirely on his/her merits. Multiracialism or multiculturalism should be viewed as Nature’s way of harmonisation, for variety lends enchantment, beauty and novelty. This is very well reflected in a poem entitled Our ColoursColour is God’s ornament, far from being a demerit,All are the same whether they eat millet or wheat bread,Eaters of wheat and lentils, living and dead,Colour is God’s ornament, far from a mark of demerit

He adorns the stars and the Heavens, roses and jasmines,Colour is God’s majesty and on the body it’s not uncleanness.It is neither a mark of bitterness, nor sin nor blemish,Colour is the beauty of the Perfect God Almighty.

Folk tales, poetry and taarab music were three elements which played an important role in the construction of the national symbols of Zanzibari culture. They were the vehicles which have always helped to convey messages of peace and tolerance. They have always propelled holistic values of love; of emotional world of fantasy, and moral values which tend to teach that the good will always triumph and the bad will always fail. They were the major weapons used to fight obscurantism. This is why it was very common to hear people judging a man not by his material wealth but by what s/he has in her/his brain, as a poet, a jurist, or a teacher. Knowledge was the major aspect which allowed a person to obtain that renown respect in the society which in Kiswahili is called heshima. Zanzibar is by all standards a cultural community whose development was made possible thanks to the spirit of tolerance. As an important component of Zanzibari culture, tolerance played a vital role in merging together all the different elements of Zanzibari society. By discouraging all kind of discriminations and encouraging mutual understanding tolerance was an important source of strength for Zanzibaris. It allowed them to be together as a people and survive different invasions throughout the history. Today as yesterday Zanzibaris future lies on their capacity to surpass the political manipulations which tend to divide them along racial lines. There is no future for Zanzibaris out of their Zanzibariness. This is clearly emphasised by Professor Sheriff “It has a history of invasions, and of assimilations of the invaders in the integrated culture of Zanzibar. It is a cultural mosaic that has a pattern and a meaning that would be lost if the pieces were separated and identified individually as African, Arab, Indian, etc, it can only be identified as Zanzibari”Ali Muhsin AL BARWANI, Conflicts and Harmony In Zanzibar (Memoirs), Dubai, 1997.Juma ALEY, Enduring Links, Zanzibar Series, Union Printing Press, Dubai, 1994.Abdulrahman Mohamed BABU, “Zanzibar and the Future” Changevol. 2 No. 4/5 April/May, Dar Es Salaam, 1994, pp. 28-33.Mohamed Ali BAKARI, The Democratisation Process in Zanzibar : A Retarded Transition, Institut für Afrika-Kunde, Hamburg, 2001.N.R. BENNETT, History of the Arab Stateof Zanzibar, Methnen, London, 1978.Richard BURTON, Zanzibar : City, Island and Coast, (2 volumes), Tinsley Brothers, London, 1872.Robert CAPUTO, Swahili Coast: East Africa’s Ancient Crossroads, National Geographic Magazine, October 2001, p. 104-119.Tominaga CHIZUKO and Abdul SHERIFF, « The Ambiguity of Shirazi Ethnicity in the History and Politics of Zanzibar » in Christianity and Culture, N° 24, 1989.Richard HALL, Empire of the Monsoon : A History of the Indian Ocean and Its Invaders, Harper Collins, London, 1996W.H. INGRAMS, Zanzibar : its history and its people, Frank Cass Ltd., London 1967.W.H. INGRAMS, Arabia and the Isles, John Murray, London, 1942.Colette LE COUR GRANDMAISON et Ariel CROZON (sous la direction de), Zanzibar aujourd’hui, Karthala-Ifra, Paris, 1998.Françoise LE GUENNEC-COPPENS et Pat CAPLAN (sous la direction de), Les Swahili entre Afrique et Arabie, Karthala, Paris, 1991. Abdulaziz Yussuf LODHI, Oriental Influences in Swahili: A Study in Language, Culture Contacts, Orientalia et Africana Gothoburgensia 15, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, 2000.Abdulaziz Yussuf LODHI, National Language, Culture and Identity: The Role of Kiswahili in the context of Zanzibar, International Conference on the History and Culture of Zanzibar, Zanzibar, 14 – 16 December,1992.Michael LOFCHIE, Zanzibar : Background to Revolution, PUP, Princeton, New Jersey, 1965.Robert Nunez LYNE, ZANZIBAR in Contemporary Times, Darf Publishers Ltd., London, 1905. B. G. MARTIN, « Notes on Some Members of the Learned Classes of Zanzibar and East Africa in the Nineteenth Century, African Historical Studies, IV, 525-545, 1971.S. H. MAULY, “Evil Is Not The Monopoly Of Any One Race: Zanzibar Political History And Development In Perspective”, Change vol. 3 No. 1/2 January/February, Dar Es Salaam, 1995, pp. 18-27.Alamin M. MAZRUI, and Ibrahim Noor SHARIFF, THE SWAHILI, Idiom and Identity of an African People, Africa World Press, Trenton, 1994.John MIDDLETON, The World of the Swahili, An African Mercantile Civilization, YaleUniversity Press, New Haven and London, 1992.Derek NURSE and Thomas SPEAR, The Swahili : Reconstructing the History and Language of an African Society, 800-1500, University of Pensylvannia Press, Philadelphia, 1985.David PARKIN, (Ed.) Continuity And Autonomy In Swahili Communities, Inland Influences And Strategies Of Self-Determination, SOAS, AFRO-PUB, London, 1994.F.B. PEARCE, Zanzibar, the Island Metropolis of East Africa, T. Fisher Unwin Limited, London, 1920.Michael N. PEARSON, Port Cities and Intruders. The Swahili Coast, India, and Portugal in the Early Modern Era, The Johns Hopkins UniversityPress, Baltimore and London, 1998. A H. J. PRINS, The Swahili-Speaking Peoples of Zanzibar and the EastAfrican Coast, IAI, London, 1961.Mohamed Ahmed SALEH, Kiswahili : Patience, humilité et dépassement moral, in Paul Siblot (Coordonné par), Dire La Tolérance, UNESCO-Praxiling, Paris, 1997, pp. 65-66.Mohamed Ahmed SALEH, “Zanzibar et le monde swahili”, Afrique Contemporaine, No. 177, 1er trimestre, La Documentation Francaise, Paris, 1996, pp. 17-29. Mohamed Ahmed SALEH, Les Pêcheurs de Zanzibar : Transformations socio-économiques et permanence d’un système de représentation, mémoire pour le Diplôme d’Etudes Approfondies (DEA), EHESS, Paris, 1995.Mohamed Ahmed SALEH, Le Grand Mariage “Ada” : La creation des notables à la Grande Comore (Ngazidja), Mémoire de l’EHESS en anthropologie sociale, Paris, 1992.Abdul SHERIFF, Slaves, Spices and Ivory in Zanzibar, (Integration of East African Commercial Empire into World Economy 1770-1873), Eastern African Studies, James Currey, London; Heinemann Kenya, Nairobi; Historical Association of Tanzania, Dar Es Salaam; Ohio University Press, Athens; 1987.Abdul SHERIFF, Historical Zanzibar - Romance of the Ages, HSP Publications, London, 1996.The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, Zanzibar A Plan for the Historic Stone Town, 1996.

The main island (Unguja) has an average area of 1 464 square kilometres and its sister island, Pemba, 868 square kilometres. The name « Zanzibar » has a triple usage. It is the name of (i) the country, (ii) the main island (which is also known as Unguja), and (iii) the Capital city of the archipelago. The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, Zanzibar: A Plan for the Historic Stone Town, (1996), p. 11. Abdulrahman M. BABU, Zanzibar and the Future, in Change vol. 2 No. 4/5 April/May, Dar Es Salaam, 1994, pp. 28-33. In Robert CAPUTO, Swahili Coast: East Africa’s Ancient Crossroads, National Geography Magazine, October 2001, p. 118. The Swahili cultural influence extends about 3 000 kilometres all along the east African coast, from Brava (Somalia) up to Sofala (Mozambique), including adjacent islands, notably Lamu, Mombasa, Pemba and Unguja (Zanzibar), Mafia, Kilwa and the Comoros Michael N. PEARSON, Port Cities and Intruders. The Swahili Coast, India, and Portugalin the Early Modern Era, The JohnsHopkins UniversityPress, Baltimore and London, 1998. Alamin M. MAZRUI, and Ibrahim Noor SHARIFF, THE SWAHILI, Idiom and Identity of an African People, Africa World Press, Trenton, 1994. Mohamed Ahmed SALEH “Zanzibar et le monde swahili”, Afrique Contemporaine, No. 177, 1er trimestre, La Documentation Francaise, Paris, 1996, pp. 17-29. Harold INGRAMSs (1942), Arabia and the Isles, p. 10. See Richard HALL, Empire of the Monsoon : A History of the Indian Ocean and Its Invaders, Harper Collins, London, 1996 Lateen-rigged wooden vessels still used today. Abdul SHERIFF and Chizuko TOMINAGA, “The Ambiguity of Shirazi Ethnicity in the History and Politics of Zanzibar”, in Christianity and Culture, N° 24, 1989. The Shirazi tradition has existed for at least five centuries. The concentration of people claiming Shirazi origin occurs along the Mrima coast and the offshore islands. There are some so-called Shirazi villages where a majority consisted of such families, or where the people identified themselves with the ruling or social elite. On the offshore islands of Unguja and Pemba, the indigenous population has come to identify itself as Shirazi in contradistinction from the more recent African and Arab immigrants. In general an important number of Zanzibaris can claim to have a foreign ancestry : persian, arab, indo-pakistanese, goanese, chinese, comorian, seychellese, mainland african. See Abdul SHERIFF and Chizuko TOMINAGA, “The Ambiguity of Shirazi Ethnicity in the History and Politics of Zanzibar”, in Christianity and Culture, N° 24, 1989. Abdul SHERIFF, in Robert CAPUTO, Swahili Coast: East Africa’s Ancient Crossroads, National Geography Magazine, October 2001, p. 113. Abdulaziz Y. LODHI, Oriental Influences in Swahili: A Study in Language, Culture Contacts, Orientalia et Africana Gothoburgensia 15, Acta Universitatis Go thoburgensis, 2000. Mohamed Ahmed SALEH, , “Kiswahili : Patience, humilité et dépassement moral”, Dire la Tolérance, UNESCO – Praxiling, Paris, 1997, pp. 65-66 Inside the Sunni branch, there are four other schools of thought: Shafi, Hambal, Malik and Hanafi. Mohamed Ali BAKARI, The Democratisation Process in Zanzibar : A Retarded Transition, Institut für Afrika-Kunde, Hamburg, 2001. p. 89 John MIDDLETON, 1992, The World of the Swahili: An African Mercantile Civilization, Yale UniversityPress, New Haven, p. 170. Maulid: Elegy of Prophet Muhammad which gives its name to the ceremony of the celebration of his birth and to the religious text celebrating his life. The Maulid day is celebrated all over the Muslim World. Barwany (Ali Muhsin), 1997, Conflict and Harmony in Zanzibar, (Memoirs), Dubai. From Al-Busaidy dynasty he was the first Sultan of Oman who moved the Capital of his Empire from Muscat (Oman) to Zanzibar in 1832. Mohamed Ali BAKARI, The Democratisation Process in Zanzibar : A Retarded Transition, Institut für Afrika-Kunde, Hamburg, 2001. p. 89 Sultan of Zanzibar from 28 October 1856 to 7 October 1870. N. R. BENNET, 1978, Arab State of Zanzibar, p. 82-83 Sultan of Zanzibar from 7 October 1870 to 27 March 1888. To date, Zanzibar has a sole government-owned weekly, Nuru. The mother-tongue of all Zanzibaris John MIDDLETON, 1992, The World of the Swahili: An African Mercantile Civilization, Yale UniversityPress, New Haven, London, p. 170. Call for prayers insufflated into a newborn. It is a common practice in the whole Swahili World. See Mohamed A. SALEH, 1992, Le Grand Mariage “Ada” : La creation des notables à la Grande Comore (Ngazidja), Mémoire de l’EHESS en anthropologie sociale, Paris, p. 58 The case of Mzee Mwanze is a very eloquent example. His pragmatism, his kind heart, his spirit of openness, popularised him in Zanzibar where he was very well known for his humanism. He devoted one day of his week visiting all the sick people admitted at the V. I. Lenin Hospital at Mnazi Mmoja, Zanzibar, and praying for them, notably for their early recovery. Apprenticing of sentiment of humility, of reservation, of moderation and of self-retaining. It is a common action in the whole Swahili World; see Mohamed Ahmed SALEH, 1995, Les Pêcheurs de Zanzibar: Transformations socio-économiques et permanence d’un système de représentation, Mémoire pour le Diplôme d’Etudes Approfondies, EHESS, Paris, p. 81. Mohamed Ahmed SALEH, 1977, “Kiswahili : Patience, humilité et dépassement moral”, Dire la Tolérance, UNESCO – Praxiling, Paris, pp. 65-66 It is important to note here that Zanzibaris do not practice female excision. Ceremonies organised before, during and after the birth of a child. See for example Evans-Pritchard (1973) for the case of Nuer in Sudan.; Mohamed Ahmed SALEH, 1992, Grand Mariage “Ada” : La creation des notables à la Grande Comore. Shaaban Robert, « Our colours », in Ali A. Jahadhmy, Anthology of Swahili Poetry – Kusanyiko la Mashairi-, African Writers Series N° 192, Heinemann, London, Nairobi, Ibadan, Lusaka, 1977, p. 4-5 Abdul SHERIFF, Historical Zanzibar: Romance of the Ages, HSP Publications, London, 1996.

Published on August 25, 2014 18:13

August 21, 2014

Zanzibar's Diverse Communities by Abdulrazak Fazal

Zanzibar's Historical Religious Tolerance - her diverse communities

Among the Indians in Zanzibar the Parsees and Goans formed fairly average sized communities. We had earlier talked about the Parsees. We now bring up the Goans. They were hardworking and flamboyant people. In actual fact they did not consider themselves Indians as Goa then was under the colonial rule of the Portuguese. Also with their Christian background and fluency in English they could easily connect themselves with the colonials. No doubt the Barretos and Carvalhos featured prominently in Zanzibar’s banks and administrative set ups. Some were specialized as tailors. A Goan tailor shop in the stone town was a common sight. They had their twin towered cathedral with statues of Virgin Mary located in Vuga beside the Samachar Printing Press across Portuguese street. What comes to mind is the spectacle of their funeral procession in Zanzibar. There was somberness about it. The cortege would be led by a cross bearer followed by a black cart with wreaths laid over it, and then the relatives carrying the coffin over their shoulders. The mourners in their black attire walked behind in dignified manner.

Some of Zanzibar’s prominent doctors like Demello, Menezes, D’silva and Maitra were Goans. The Goans also excelled in sports. They had their ‘Goan Club’ and ‘Goan Institute’. The burly James D’lord was one of Zanzibar’s hardest hitter of the cricket ball. The Goans along with Hindus and Comorians were dominant in field hockey. Their school, St. Joseph Convent, run by the Catholic Mission was one of Zanzibar’s most prestigious school that admitted besides Catholic only selective non-Catholic pupils. The school was located behind the High Court which was on the main Shangani Road where many Goans resided. The road stretched up to the Post Office at the far end of Portuguese street where mainly the Hindu community resided.

The Hindus in Zanzibar were an enterprising community, and foremost among them were the Bhatias. It is said that the brothers Jeraj and Eebji Shivji were the first to settle in Zanzibar. Later their surname Shivji changed to Swaly which is derivative of the term ‘Swahili’. Narandas Swaly, a reputed contractor, whose expertise our forefathers sought in having their walls and ceilings bricked up, and Vinod Swaly, a very popular teacher at the Agakhan Secondary School, were the descendents of Eebji Swaly.

Here we need to point up a significant and historic incident. It was the visit of Mahatma Gandhi to Bhatia Mahajanvadi at Ziwani en route from South Africa to India. There is an interesting anecdote relating to this episode. Gandhiji refused to enter the Bhatia Mahajanvadi building as there was a notice saying 'Bhatia sivay koine andar aavavani raja nathi' (only Bhatias are allowed to enter) . That really embarrassed the committee. The notice was immediately removed and after persuasion Gandhiji consented to enter the building. Years later in 1948 Gandhiji was assassinated and sadly this time his ashes brought to Zanzibar when a large number of Asians gathered at the dock as a mark of respect for this great Mahatma. The ashes were then taken to Jinja (Uganda) to be scattered in the Nile.

The Hindus observed diwali with great pomp and ceremony. The diwali illumination brightened up Shangani/Portuguese/Hurumzi (Vaddi Bhajaar) streets and they burst with crackers. On the eve of Diwali ‘chopra puja’ was held in every shop. Even Muslim shopkeepers participated in this ‘puja’. Every Indian shopkeeper had his ‘namu’ (accounts) done in ‘Gujarati’ and he closed his books to transfer the balances into the new ones on the Hindu New Year. Also the rupee was Zanzibar’s legal tender. The Bhatias were held in very high esteem by the Sultan and some even acted as advisers to him. The Jetha Leela private bank located in Portuguese street may be recorded as one of the oldest financial institutions in East Africa. The street also housed the clinics of the well known Hindu doctors - Dr. Goradia, Dr. Mehta and Dr. Patel who were immensely popular with the settlers.

Zanzibar was indeed blessed with great professionals and formidable intellects. The round clock protruding from the building on Shangani signified Zanzibar's High Court. Its Chief Justice, Sir John Grey, formed an authority on Zanzibar's judicial system. Other prominent personalities included Judge Green, Magistrate Husain Rahim and Registrar Husain Nazarali. Zanzibar boasted a Secular Court and a Sharia Court. Sheikh Omar Smet and Abdullah Saleh Farsi were Chief Kadhi for the Sharia Court. The Talati brothers of 'Wiggins and Stephens' and the Lakha brothers were some of Zanzibar's leading lawyers. Wolf Dourado went on to become the Attorney General in the post Revolution phase.

Zanzibar's oldest newspaper was a weekly Samachar published by Fazel Master whose establishment dated back to 1903. The bilingual (English and Gujarati) paper was circulated on Sundays only. Such another was 'Zanzibar Voice' by Ibrahim Kassam. Also Rati Bulsara entered with his very own Adal Insaaf. The Government Press besides the gazette delivered Maarifa on Thursdays.

Portuguese street adjoined Sokomohogo/Mkunazini streets which were largely occupied by the Bohoras who were old settlers and dealt in hardware, crockery or had tin/glass cutting workshops. They had as many as three mosques which were situated at Kiponda, Mkunazini and Sokomohogo. Their gym/club was the finest with excellent facilities. The famed Karimjee Jivanjee family belonged to the Bohora community. Two of the Karimjee brothers were honoured with knighthood by the British Colonial Government, Sir Yusufali & Sir Tayabali. The late His Holiness Syedna Taher Saifuddin paid a visit to Zanzibar in the late 1950s (or was it early 1960s?). On that occasion the Bohora Scout troop displaying their classic band marched majestically through the streets of stone town. At night Mkunazini and Sokomohogo were transformed into a glitter. The spacious Bohora School compound exhibited spectacular replica of the ‘Sefi Mahal’ (Syedna’s Bombay mansion). In adherence to the salutary advice by Syedna a great number of Bohoras staked their livelihood in Zanzibar. Presently theirs is the largest community abounding in prosperity..

There was great concentration of Kutchi Sunnis too in Mkunazini/Sokomohogo. They comprised Memon, Khatri, Sonara, Sumra, Surya, Loharwadha, Girana, Juneja, Sameja, Chaki, Kumbhar, Hajam, Bhadala and such Kutchi artisan/smith communities. There were also Sunni communities other than Kutchi such as Kokni (Muslims from Maharashtra) and Surti Vora (Muslims from Surat, Gujarat). Equally early settlers were the Kutchi Sunnis. As a matter of fact our forefathers were brought to Zanzibar in dhows navigated by the Kutchi Sunnis. In the instance of Kutchi Kumbhars (a pottery class) some inhabited Makunduchi. They built up contacts with the locals there, spoke fluent Kiswahili and attended school in Makunduchi where medium of instruction was Kiswahili. The owners of ‘Sura Store’ and ‘Muzammil’ who were destined to flourish in the post Revolution phase are the progeny of this ancestry.

Portuguese street also converged on Hurumzi (Vaddi Bhajaar) where the Hindu and Jain temples were located. The street extended up to Saleh Madawa's shop or the monumental Ismaili Jamaatkhana that stretched all the way from one road to another. It formed terminus for several by-ways and lanes that headed towards the Khoja dominated Kiponda/Malindi. In the early days the Ismailis had jamaatkhana even in Sateni, Bumbwini and Chwaka. Obviously the Khojas (Ithnashris & Ismailis) formed the bulk of the settlement (amply evidenced by the earlier days’ census)) and were scattered all over Zanzibar including Ngambu, Bububu, Mfenesini, Bumbvini, Chwaka and Makunduchi.

Among the Indians in Zanzibar the Parsees and Goans formed fairly average sized communities. We had earlier talked about the Parsees. We now bring up the Goans. They were hardworking and flamboyant people. In actual fact they did not consider themselves Indians as Goa then was under the colonial rule of the Portuguese. Also with their Christian background and fluency in English they could easily connect themselves with the colonials. No doubt the Barretos and Carvalhos featured prominently in Zanzibar’s banks and administrative set ups. Some were specialized as tailors. A Goan tailor shop in the stone town was a common sight. They had their twin towered cathedral with statues of Virgin Mary located in Vuga beside the Samachar Printing Press across Portuguese street. What comes to mind is the spectacle of their funeral procession in Zanzibar. There was somberness about it. The cortege would be led by a cross bearer followed by a black cart with wreaths laid over it, and then the relatives carrying the coffin over their shoulders. The mourners in their black attire walked behind in dignified manner.

Some of Zanzibar’s prominent doctors like Demello, Menezes, D’silva and Maitra were Goans. The Goans also excelled in sports. They had their ‘Goan Club’ and ‘Goan Institute’. The burly James D’lord was one of Zanzibar’s hardest hitter of the cricket ball. The Goans along with Hindus and Comorians were dominant in field hockey. Their school, St. Joseph Convent, run by the Catholic Mission was one of Zanzibar’s most prestigious school that admitted besides Catholic only selective non-Catholic pupils. The school was located behind the High Court which was on the main Shangani Road where many Goans resided. The road stretched up to the Post Office at the far end of Portuguese street where mainly the Hindu community resided.

The Hindus in Zanzibar were an enterprising community, and foremost among them were the Bhatias. It is said that the brothers Jeraj and Eebji Shivji were the first to settle in Zanzibar. Later their surname Shivji changed to Swaly which is derivative of the term ‘Swahili’. Narandas Swaly, a reputed contractor, whose expertise our forefathers sought in having their walls and ceilings bricked up, and Vinod Swaly, a very popular teacher at the Agakhan Secondary School, were the descendents of Eebji Swaly.

Here we need to point up a significant and historic incident. It was the visit of Mahatma Gandhi to Bhatia Mahajanvadi at Ziwani en route from South Africa to India. There is an interesting anecdote relating to this episode. Gandhiji refused to enter the Bhatia Mahajanvadi building as there was a notice saying 'Bhatia sivay koine andar aavavani raja nathi' (only Bhatias are allowed to enter) . That really embarrassed the committee. The notice was immediately removed and after persuasion Gandhiji consented to enter the building. Years later in 1948 Gandhiji was assassinated and sadly this time his ashes brought to Zanzibar when a large number of Asians gathered at the dock as a mark of respect for this great Mahatma. The ashes were then taken to Jinja (Uganda) to be scattered in the Nile.

The Hindus observed diwali with great pomp and ceremony. The diwali illumination brightened up Shangani/Portuguese/Hurumzi (Vaddi Bhajaar) streets and they burst with crackers. On the eve of Diwali ‘chopra puja’ was held in every shop. Even Muslim shopkeepers participated in this ‘puja’. Every Indian shopkeeper had his ‘namu’ (accounts) done in ‘Gujarati’ and he closed his books to transfer the balances into the new ones on the Hindu New Year. Also the rupee was Zanzibar’s legal tender. The Bhatias were held in very high esteem by the Sultan and some even acted as advisers to him. The Jetha Leela private bank located in Portuguese street may be recorded as one of the oldest financial institutions in East Africa. The street also housed the clinics of the well known Hindu doctors - Dr. Goradia, Dr. Mehta and Dr. Patel who were immensely popular with the settlers.

Zanzibar was indeed blessed with great professionals and formidable intellects. The round clock protruding from the building on Shangani signified Zanzibar's High Court. Its Chief Justice, Sir John Grey, formed an authority on Zanzibar's judicial system. Other prominent personalities included Judge Green, Magistrate Husain Rahim and Registrar Husain Nazarali. Zanzibar boasted a Secular Court and a Sharia Court. Sheikh Omar Smet and Abdullah Saleh Farsi were Chief Kadhi for the Sharia Court. The Talati brothers of 'Wiggins and Stephens' and the Lakha brothers were some of Zanzibar's leading lawyers. Wolf Dourado went on to become the Attorney General in the post Revolution phase.

Zanzibar's oldest newspaper was a weekly Samachar published by Fazel Master whose establishment dated back to 1903. The bilingual (English and Gujarati) paper was circulated on Sundays only. Such another was 'Zanzibar Voice' by Ibrahim Kassam. Also Rati Bulsara entered with his very own Adal Insaaf. The Government Press besides the gazette delivered Maarifa on Thursdays.

Portuguese street adjoined Sokomohogo/Mkunazini streets which were largely occupied by the Bohoras who were old settlers and dealt in hardware, crockery or had tin/glass cutting workshops. They had as many as three mosques which were situated at Kiponda, Mkunazini and Sokomohogo. Their gym/club was the finest with excellent facilities. The famed Karimjee Jivanjee family belonged to the Bohora community. Two of the Karimjee brothers were honoured with knighthood by the British Colonial Government, Sir Yusufali & Sir Tayabali. The late His Holiness Syedna Taher Saifuddin paid a visit to Zanzibar in the late 1950s (or was it early 1960s?). On that occasion the Bohora Scout troop displaying their classic band marched majestically through the streets of stone town. At night Mkunazini and Sokomohogo were transformed into a glitter. The spacious Bohora School compound exhibited spectacular replica of the ‘Sefi Mahal’ (Syedna’s Bombay mansion). In adherence to the salutary advice by Syedna a great number of Bohoras staked their livelihood in Zanzibar. Presently theirs is the largest community abounding in prosperity..

There was great concentration of Kutchi Sunnis too in Mkunazini/Sokomohogo. They comprised Memon, Khatri, Sonara, Sumra, Surya, Loharwadha, Girana, Juneja, Sameja, Chaki, Kumbhar, Hajam, Bhadala and such Kutchi artisan/smith communities. There were also Sunni communities other than Kutchi such as Kokni (Muslims from Maharashtra) and Surti Vora (Muslims from Surat, Gujarat). Equally early settlers were the Kutchi Sunnis. As a matter of fact our forefathers were brought to Zanzibar in dhows navigated by the Kutchi Sunnis. In the instance of Kutchi Kumbhars (a pottery class) some inhabited Makunduchi. They built up contacts with the locals there, spoke fluent Kiswahili and attended school in Makunduchi where medium of instruction was Kiswahili. The owners of ‘Sura Store’ and ‘Muzammil’ who were destined to flourish in the post Revolution phase are the progeny of this ancestry.

Portuguese street also converged on Hurumzi (Vaddi Bhajaar) where the Hindu and Jain temples were located. The street extended up to Saleh Madawa's shop or the monumental Ismaili Jamaatkhana that stretched all the way from one road to another. It formed terminus for several by-ways and lanes that headed towards the Khoja dominated Kiponda/Malindi. In the early days the Ismailis had jamaatkhana even in Sateni, Bumbwini and Chwaka. Obviously the Khojas (Ithnashris & Ismailis) formed the bulk of the settlement (amply evidenced by the earlier days’ census)) and were scattered all over Zanzibar including Ngambu, Bububu, Mfenesini, Bumbvini, Chwaka and Makunduchi.

Published on August 21, 2014 23:09

April 28, 2014

ZANZIBAR REVOLUTION REVISITED – a short review essay by Prof. Abdulaziz Y. Lodhi.

Review of: Amrit Wilson (2013). The Threat of Liberation: Imperialism and Revolution in Zanzibar. Pluto Press, London. XII 175 pp.

Zanzibar todayZanzibar has too much history and too little geography!A well-known commercial slogan to promote dollar tourism in Zanzibar echoes ‘If you want to experience Paradise, visit Zanzibar!’ In the past, European colonialists, with more than a pinch of sensation, described these ‘Spice Islands’ as ‘When you play the flute in Zanzibar, people dance as far as in the lakes region of the interior of Eastern Africa!’ Later in the Cold War jargon, the Western press called this archipelago ‘the Cuba of East Africa’ and ‘the Clove Curtain’ during the roaring 1960s and 1970s respectively. One can find several shelf-metres in the libraries around the world having materials on Zanzibar. The name ‘Zanzibar’ has been exploited by many to sell their books and other works which have nothing to do with Zanzibar as such.1

Today, the semi-autonomous People’s Republic of Zanzibar is a densely populated junior member of the United Republic of Tanzania, heavily dependent on diaspora remittances, foreign aid and dollar tourism, constantly at logger-heads with the Union Government on Mainland Tanzania. Half of its population is under the age of 16. Most luxury tourist hotels are foreign-owned, employing a large proportion of Mainlanders or foreigners who do not have Zanzibari trade union affiliation and the associated social security. Most souvenirs and the bulk of spices for sale to tourists and local consumption are imported, except for cloves, chilly and cinnamon. The per capita consumption of food and beverages, water, electricity, vehicles, fuel etc by the tourists is grossly higher than that of the locals, and much of all this is imported, reducing drastically the net income from tourism. Together with ITC, Tourism is a top official priority in Zanzibar to boost economic development.

During the early years after the Revolution in January 1964, Zanzibar experienced political, economic and social stagnation. However, during the recent decades, it has made many strides in the right direction to modernize the country and develop an egalitarian society, with a multi-party parliamentary system. The hard-handed early revolutionary rulers grossly mismanaged the country and created even greater inequalities, limitless oppression, systematic suppression of all human rights, harassment and confiscation of private properties handed over to political and bureaucratic leaders, with corruption from top to bottom in the administration which was mostly based on nepotism.2

Today the country can boast of two universities and several university colleges, several modern clinics etc; however, its capital city the Stone Town (Kijiweni) still suffers from water and power cuts, problems of garbage collection and disposal, crime, violence and robbery. Increasing cases of rape, drug problems, Aids, prostitution and pedophilia are reported daily.

Zanzibar before 1964 was one of the most prosperous and developed countries in Africa, with a minimum of crime, almost free education and health services, low-cost electricity and water supply etc, albeit suffering from feudalism coupled with compradorial economics (whereby much East African trade in ivory, gold, diamonds and similar goods was controlled by Zanzibaris), and the resulting dichotomy of urban and rural populations and contradictions contained therein. Early party politics in Zanzibar were infected by racial/ethnic unrest, mostly aggravated by its recent history of Omani colonization of the coast of East Africa and many inland urban centres, plantation and domestic slavery and slave trade - slaves brought to Zanzibar for local employment or export to Mombasa for work on coconut plantations on Kenya coast, farms in the Juba Valley in Southern Somalia, and date plantations in Oman, had been bought from local chiefs in the interior of eastern Africa, or randomly caught, mostly in north-eastern, central and south-eastern regions of Tanganyika, eastern Congo and south-eastern Kenya.3

Amrit Wilson’s present bookMuch has been written on the 1964 Revolution in Zanzibar.Dr. Amrit Wilson’s present book has come out timely when Zanzibar is hectically planning and organizing to celebrate on 12 January 2014, the 50th anniversary of the Revolution of 1964, which toppled the one month old coalition government of the Zanzibar Nationalist Party (ZNP) and the Zanzibar and Pemba People’s Party (ZPPP) with its constitutional monarch Seyyid Jamshid bin Abdullah, the 12th and last Sultan of Omani patriline. The new revolutionary government was formed by the odd couple, the large and corrupt Afro-Shirazi Party (ASP) 4 led by its charismatic populist Chairman Sheikh Abeid Aman Karume and the small radical Umma Party (UP) led by the Marxist journalist Comrade Abdulrahman Mohamed Babu supported by the marginal Zanzibar Communist Party (ZCP) led by the Maoist Abdulrahman ‘Gai’ Hamdani.

The book, with its 8 chapters and more than a dozen rare photographs of historical importance to Zanzibar, is a well-researched study by a respected author of long-standing. It outlines the dramatic history of Zanzibar and its anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggles, the British transfer of power to a royalist coalition government, and the subsequent overthrow of that government followed by neo-imperialist coercion to stifle the Wind of Change in Africa by high-jacking the Zanzibar Revolution and constructing the Union of Tanzania.

Under the insulating umbrella of this Union, the new revolutionary leaders turned increasingly anti-intellectual and developed Zanzibar into a police state using extreme violence and tyranny that is typical of dictatorial governments and despotic rulers. This ultimately resulted in the catastrophic assassination of the first President of the People’s Republic, Sheikh Karume, in 1972.

The first 5 chapters treat well the anti-colonial struggles in Zanzibar, the British transfer of power to the royalist coalition, the Revolution and the Imperialist fears, the union with Tanganyika, and the first decade of despotic rule. Chapter 6 of the book treats in detail the “Kangaroo Court” of Zanzibar, the trials of the progressive elements, their long imprisonment and exile. As vestiges of that period, with the demise of the legal system and a culture of nepotism, one witnesses rife corruption even today and court cases that have been going on for 15 to 20 years without any final judgement in sight!

The important role of the Umma Party and its Marxist visionary leader Comrade Babu in radicalizing the politics of Zanzibar is highlighted throughout the captivating narrative.5 The book is thus also a tribute to Professor Babu and his Umma Party. The last two chapters deal with the current state of the Union and the increasingly strained relations between the Islands and the Mainland. The Islanders demand among other changes, equal representation at all levels and in all union organs as it is claimed it was categorically expressed by Sheikh Karume – Nusu bi nusu! (50/50). It seems the Union will soon develop into a federation with separate state governments for Tanganyika and Zanzibar, under the umbrella of a small Federal Government as it was understood by many in the beginning, leading eventually to an East African Federation.

The Zanzibar Revolution was bloody, as all revolutions are! A Revolution is a kind of civil war in which thousands are killed, and it leaves many wounds unhealed for long and their ugly scars remain forever. In the aftermath of the Zanzibar Revolution, several thousand people were remanded or jailed for short or long periods without trial, and a couple of hundred of them were summarily tried and sentenced to death – many of them buried in hidden or unmarked graves or thrown in the sea.

The Zanzibar Revolution was carried out with outside help and immigrant elements in the country, and it echoed racial tones. The revolutionaries and their leaders were of all ethnic and mixed origins, and the new rulers tried to rectify the ethnic/racial imbalance that had been cemented by the British colonial rule based on a prodigal aristocracy and indebted feudal class fraternizing with rising merchant and industrialist classes, both of mostly non-African origin, specially South Asian. According to the December 1958 Census of Zanzibar, which was also a kind of social survey with 32 questions, the population of Zanzibar 5 years before the Revolution numbered only about 360 000 souls, and they had perceived their ethnic origins as follows and identified themselves as such:

Shirazi Africans 56% Mainland Africans 19% Arabs 17% (Omanis, Yemenis, mixed Arab-African-Indian origins)Indians 6 % (Sunni Muslims, Shia Ismailis, Shia Ithnaasheri, Shia Bohora, Hindus, Jains, Ceylonese Budhists, Indian Parsis, Goans and other Indian Catholics)Others 2% (including Comorians, Somalis, Shia Bahrainis etc)

Soon after the Revolution, the new government classified the population of Zanzibar as 80% African, 15% Arab, 4% Indian and 1% Others. This was the quota used by the Ministry of Education under the Marxist leader Comrade Ali Sultan Issa, a so-called ‘Arab’ by patrilineal origin, to allocate secondary school places to students for a couple of years to redress the imbalance of admission to secondary schools which was a result of the dichotomy of the rural (mostly African) versus the urban (mostly non-African) communities. No such ‘racial’ criteria were used for access to higher education, however, during the first year of the Revolution, in state and local government employment, some amount of selective ethnic cleansing was practiced to remove non-citizens and Zanzibari citizens of Arab, Iranian and Indo-Pakistani origin. Most Zanzibaris are of mixed origins, essentializing their agnatic descent in different social and political contexts. With a minimum of meritocracy, the bureaucrats of Zanzibar were recruited in the early revolutionary administration primarily through pure nepotism and favoritism. Zanzibaris of today are much more ethnically mixed then they were 50 years ago.

About one fifth of the population, including many semi-permanent migrant workers and non-citizens, mostly males, were born in Tanganyika or other parts of eastern Africa. About 2000 of them including more than 600 policemen, 60% of the Police, did not adhere to Islam, the religious conviction of 98% of Zanzibaris at that time. This was crucial in bringing the ASP close to the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) on which ASP depended quite much financially, finally leading to the formation of the Union of Tanzania which the Western powers indirectly imposed on Zanzibar to contain the leftist Revolution – the alternative for Zanzibar was to face a Western-supported rightist invasion from the Portuguese occupied Mozambique. This may have been an empty threat, but it did work. Some researchers have strongly argued that the Union of Tanzania is a Cold War construction, and therein lies the main cause of the current constitutional crisis that has been shaking the United Republic.One immediate consequence of the Revolution was the closing down of several factories producing coconut oil, soap and oil cake used as cattle feed, many furniture and mechanical workshops, dozens of shops producing garments, shoes and other consumer goods, a couple of hundred businesses dealing with import of piece goods and their further export to the rest of eastern African, and the loss of trade in ivory, gold and diamonds, created a mass exodus of people to the rest of East Africa, primarily Tanganyika, which also gained much from the braindrain of Zanzibar.6

Amrit Wilson’s fluent narrative includes meticulous details with deep insight and convincing analysis of the colonial condition in Zanzibar and the neo-colonialism it has been subjected to. The story is based on much material previously unavailable including personal narratives of and interviews with many who were involved in the different events that have shaped modern Zanzibar.

The Revolution high-jacked and the people betrayedThe 1964 Revolution in Zanzibar, which started as a rather badly planned insurgency by certain sections of the opposition alliance of ASP and UP, and which took both the CIA and the world at large by surprise, gave high hopes of constructive changes in many parts of Africa; it had far-reaching implications on the politics of eastern Africa in particular and the Cold War in general in the region. One immediate consequence of this Revolution was the army mutinies in Tanganyika, Kenya and Uganda, which were effectively dealt with by help from Britain and Nigeria. The African Revolution was thus high-jacked in its infancy and the people were betrayed by the new elites. Later, far-reaching socialist attempts at socio-economic reforms on Mainland Tanzania in the form of Mwalimu Nyerere’s much-discussed and commented Ujamaa “experiments” were also sabotaged by the mostly Western-educated bureaucracy, and as once aptly expressed by Professor Issa Shivji and reiterated by his colleague the late Professor Haroub Othman, “The Revolution in Tanzania Mainland was also betrayed in the same way.”

Amrit Wilson’s present book offers the most complete and detailed description so far of the events in Zanzibar, based on reliable sources and first-hand accounts, which can be verified by those who were active participants in those developments, (including the present reviewer who was an active student and youth leader during the 1960s before he went into self-exile in 1968 after a short period of political detention in Dar-es-Salaam and Zanzibar).

Today’s official slogan in Zanzibar is “Mapinduzi daima!” (Revolution forever!). Revolution, Yes! But Zanzibar, Tanzania and the rest of Africa needs a Mapinduzi ya Mawazo(Mental Revolution), to learn from the past, to appreciate the present and to plan and work for a better future! Tanzania has vast natural resources, a developed educational system, intellectual capacity and most Tanzanians have the willingness and desire to march forward peacefully! As Mwalimu Nyerere said, “It can be done – play your part!”7

After many years of monolithic rule which had outlawed parliamentary democracy by an oral Presidential Decree, Zanzibar has matured and through both national and international efforts, Zanzibaris with various political sympathies have succeeded in forming a Government of National Unity (GNU). The proposal for such a coalition government of all political parties was suggested already in 1963, a few months before Independence from Britain and the subsequent republican takeover with Marxist and racial overtones. Had such a government been formed at that time, the violent Revolution could have been avoided, and neither Amrit Wilson’s present book nor the present review essay would have been written!8

“The growth of Black Nationalism, the suspicion of continuity of ‘Arab’ domination coupled with propaganda that refreshed memories of slavery and the slave trade era, caused great disruption in the social equilibrium with the determination of the lower classes to end the long years of inferiority through a violent revolution. The Zanzibar Revolution of 1964, though basically a class revolution, has echoed many racial tones, for the socio-economic classes followed closely the weak – but traditional – ethnic distinctions.

The institution of slavery, though not foreign to East Africa, was escalated by non-African peoples and commercialized with de-humanizing effects on the African populations. In Zanzibar, which had been the citadel for the East African slavery and slave trade in the last century, and where servitude in some form continued to exist, the last vestiges of slavery were formally destroyed in 1964. (Abdulaziz Y. Lodhi: The Institution of Slavery in Zanzibar and Pemba. Research Report No. 16. 1973. Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, Uppsala. p.30-31)”

Amrit Wilson’s book necessarily deserves a wide audience, not only comprising concerned Zanzibaris and Tanzanians, but also all interested in eastern African affairs and the phenomenon of Revolution in general.

1 John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar (1968) is a 582 pages thick dystopian science-fiction novel, again saying nothing about Zanzibar proper. Mary Margaret Kaye’s Death in Zanzibar (1983) is a novel involving European characters in Zanzibar setting, similar to her other books such as Death in Kenya and Death in the Maldives. In Michael Morpurgo’s famous children’s adventure novel The wreck of the Zanzibar of 1995, “Zanzibar” is the name of the ship that is wrecked. The contents of Johanna Ekström’s half a dozen short Swedish poems in verse under the title “Dikter från Zanzibar” (Poems from Zanzibar) published in the Swedish literary magazine KARAVAN No. 4/2001, specially dealing with literature in the Third World, have nothing to do with Zanzibar. They were written while she was on vacation there. Magnus Eriksson has pointed this out in his review in the Stockholm morning paper Svenska Dagbladet, 14 January 2002, criticizing the editors of KARAVAN for including Swedish literature in this journal using such headings as “Poems from Zanzibar” and mislead readers. Aidan Hartley (2004) The Zanzibar Chest: A Story of Life, Love, and Death in Foreign Lands, is essentially an exciting account of the author's own experiences as a hot spots journalist covering the forgotten wars such as in Rwanda, Burundi, Congo, Somalia, Sudan and Ethiopia, blending some pieces of his family history and tales of exploits of his parents’ friends in this narrative. This story is not about Zanzibar at all! David Chrystal (2008) As they say in Zanzibar. OUP, is a 720 pages long collection of more than 2000 proverbs from 110 countries around the world; it however contains only a couple of Kiswahili proverbs!

2 The terror of this period of the police state in Zanzibar is well-depicted in the Kiswahili novel of ‘Comrade’ Hashil Seif Hashil (1999) Wimbi la ghadhabu (Wave of terror). This short novel is being currently translated into both English and Swedish by two different trranslators. Professor Said Ahmed Mohamed Khamis’ novel (1989) Asali chungu (Bitter honey) describes the decadent lifestyle of some section of the upper class before the Revolution; and Ustaadh Adam Shafi Adam’s Kasri ya Mwinyi Fuad (The Palace of Lord Fuad) of 1978 gives a good picture of life on a large plantation just before and after the Revolution and the patrician lifestyle of the absentee landlord. Ustaadh Adam Shafi’s other Kiswahili novel KULI (The coolie) of 1979 deals with another important episode in the history of Zanzibar documented in detail by Dr. Anthony Clayton of Sandhurt Military Academy, England, in his The 1948 Zanzibar General Strike (1979), Research Report No. 32. Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, Uppsala. See also Anthony Clayton (1981) The Zanzibar Revolution And Its Aftermath. Hurst & Co., London.

3 The Slave Trade in Zanzibar and its dominions was abolished in 1873 by Sultan Seyyid Barghash (the third Sultan, whose mother was an Ethiopian concubine). From 1890 when the Sultanate of Zanzibar was reduced to its present size by the Europeans and it became a British Protectorate, slaves could buy their freedom, which many urban slaves did – these could afford it as customarily they could work on their own for three days every week and earn some cash.

During 1897 to 1909, the government agreed to pay compensation to slave owners for manumission of male slaves while concubines were to become legal wives and their children declared legitimate heirs to their fathers. Altogether 4 278 slaves became free in this way. The legal status of slavery was finally abolished in 1911 when Zanzibar was transformed into a constitutional monarchy with the new Sultan Khalifa bin Haroub, the 10thSultan of Zanzibar who had succeeded his brother-in-law Seyyid Ali who had abdicated while on a visit to England. Altogether 17 293 slaves were freed for a total of £32 502 as compensation to slave owners.

Professor Edward Batson’s A Social Survey of Zanzibar conducted duering 1948-49 and published by the Zanzibar Government Printer in 1962, gave the following figures for landless male Africans in Zanzibar:Zanzibar Town/Urban: 2 220 Shirazi/Native Africans - 6 630 Mainland/Non-native Africans. Rest of Zanzibar: 1 720 Shirazi/Native Africans - 8 600 Mainland/Non-native Africans

Mainland/Non-native Africans included both a few surviving freed slaves and immigrant Africans from the other East African countries, mostly Tanganyika.

During 1948-49, a total of 19 170 adult male Africans, 3 940 natives and 15 230 adult Mainland Africans, were landless; so were also most of the Indian and Arab Zanzibaris, both urban and rural. However, during 1964-65 the Revolutionary Government gave altogether 22 000 landless Zanzibaris of all origins including many urban dwellers with no agrarian background, mostly on Unguja Island, 3 acres of plantation land which had been confiscated from former landowners. Most of these ‘landless Africans’ were Mainlanders! Much such land was also taken over by revolutionary leaders and their relatives or friends. During the first decade, the new leaders of Zanzibar lived lavishly on confiscated properties and embezzled public funds.

For details on Slavery and Slave Trade in Zanzibar, see A. Y. Lodhi (1973), The Institution of Slavery in Zanzibar and Pemba. Research Report No. 16. Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, Uppsala. This publication can be downloaded free from the website of the Nordic Africa Institute, Uppsala.See also A. Y. Lodhi, et al (1979). A Small Book On Zanzibar. Writers Book Machine, Stockholm. p. 64-70.

4 At the time of Revolution, the ASP was almost bankrupt while several of its leaders including Sheikh Karume had bought property in Tanganyika. In the early evening of the Revolution, one prominent ASP leader, Sheikh Mtoro Rehani, whose parents were Wazigua from Tanganyika, had been chased into hiding by an angry crowd of ASP Youth League members for embezzling the funds of the ASP Miembeni Branch, the former HQ of the African Association of Immigrant Workers and the Club House of the very active African Sports Club, the forerunners of ASP. The crowd vandalized the Club House, but a few days later, not surprisingly, Sheikh Mtoro Rehani was appointed the new Mayor of Zanzibar City by the Revolutionary Government.

Immigrant members of the ASP conceived the party as a Saving Society, and in their Membership Card the name(s) of the heir(s) of the Member was/were mentioned on the understanding that the collected Membership Fee would be returned to Members if or when they left the Party or if the party was to be dissolved, or it would be inherited by his/her heir(s). Almost all the immigrant members of ASP were male.

5 See also A. M. Babu (1981), African Socialism or Socialist Africa?Zed Press, London

6 Many educated Zanzibaris dismissed from the civil service were given responsible positions on the Mainland. Zanzibari primary school headmasters became principals at secondary schools in Tanganyika, and Zanzibari secondary school teachers became college teachers and university lecturers, some of them ultimately becoming professors at institutions in the West e.g. Maalim Ali Ahmed Jahadhmi and Maalim Sultan Mugheiri in the US, and Maalim Salim Kifua in Japan. Some of them like Maalim Shaaban Saleh Farsy and Maalim Said Iliyas were commissioned to translate the Military Code and the laws of Tanzania into Kiswahili; and Maalim Jaafar Tejani, an Cutchi Indian by origin, was selected to organize the Institute of Kiswahili Research at the University of Daressalaam and lead the Kiswahili Dictionary Programe sponsored by the President’s Office.

7 See Haroub Othman, Ed. (2001), BABU – I Saw The Future And It Works. E & D, Daressalaam.

8 In early September 1963, upon a suggestion from the Umma Party leader Comrade A. M. Babu, the Umma Students’ wing contacted the non-party All Zanzibar Students’ Union (AZSU) to arrange a Brainstorm and invite all political parties and their affiliated organizations to discuss the possibility of forming an All-Party National Government that would lead Zanzibar to Uhuru. Those attending the Brainstorm unanimously proposed that the first government of free Zanzibar should be a National Government since Zanzibaris of all political colours had together fought for Uhuru and that it was the whole country which was becoming free, not only the coalition parties which had won the elections based on the colonial model and organized by the colonial power. The invitation to participate in the Brainstorm was sent to all political parties, women’s unions and trade unions but no political party participated in the deliberations; however, some officials of the Zanzibar and Pemba Federation of Labour (ZPFL/ASP) with its leader Hassan Nassor Moyo, and the Federation of Progressive Trade Unions/Umma Party) including Ahmed Badawy Qullatein did attend the meeting and actively participated in the discussions. The Brainstorm was chaired by Miss Sheikha Ali Al-Miskry, Chairman of AZSU, and the present reviewer, Vice Chairman of AZSU, acted as the Secetary.

About a month later, on UN Day on 24 October 1963, at a function organized by the Zanzibar UN Student Commission (in cooperation with the UN Information Office in Daressalaam), at the Haile Selassie Hall, the ASP leader Sheikh Karume and the ZNP leader Sheikh Ali Muhsin, both informed the present reviewer that it was too late to form a National Government of all parties together as “……. we have already put our signatures at the meeting in England”.

About a year after the Revolution, President Karume told the present reviewer in his office at the ASP Head Quarters “That government of all Zanzibaris that you young people had proposed last year, we have it now, under the umbrella of ASP. Now we are all Wana wa Afro-Shirazi (Children of ASP).”

Dr. Amrit Wilson (b. 1941, India) is a UK-based veteran writer and activist.Her other works include:Finding A Voice - Asian Women In Britain. 1978.US Foreign Policy and Revolution: The Creation of Tanzania. 1989. Women and the Eritrean Revolution: The Challenge Road . 1991. The Future that Works: Selected Writings of A.M. Babu. 2002. (With Salma Babu)Dreams, Questions, Struggles: South Asian Women in Britain. 2006.

Dr. Abdulaziz Y. Lodhi (b. 1945, Zanzibar) is Professor Emeritus at the Dept. of Linguistics and Philology, Uppsala University, Sweden. He has published extensively on Swahilistics, East African Social Studies and Zanzibar Affairs. Currently he is also a Member of the International Scientific Committee (ISC) of the Slave Route Project: History and Memories for Dialogue, Unesco, Paris.

Published on April 28, 2014 16:54

January 13, 2014

That Fateful Day, Half a Century Ago (Khoja Perspective) by Abdulrazak Fazal

12 January 1964 - 12 January 2014

Talking of Zanzibar’s Khojas, they came in dhows to Zanzibarsince the mid nineteenth century (even earlier) and with the passage of time lost all the traces of their contacts in India. They were simple, peace loving and God fearing people. There was immense brotherhood among them and they cared for each other. Economically they were contented and mostly worked in Government offices where administration was excellent. Those who had business maintained only minimum margin of profit that resulted in high purchasing power and generally a good standard of living. They did not have the slightest inkling of such a revolution and were visibly shaken by it.

The past has flown fast and times have changed completely. The social, economic and political changes have had tremendous effect on our lives. It is exactly 50 years since that fateful day in Zanzibar. Sadly a large number has passed away. The anniversary has awakened poignant memory of the Zanzibardays. Today only a handful Khojas emanating from our Zanzibardiaspora remain in Zanzibar.

The moderate policy of the government of the day (in line with its mainland counterpart, their merger resulting in TANZANIA, at times at loggerheads) gives them confidence of staking their fortune in Zanzibar and cultivate loyalty towards it. The rest (now with grown up generation), wherever they are settled (some prosperous, some languishing in poverty), still find themselves attached to Zanzibarculturally. They speak Swahili among themselves. The photo albums fattened by the old black and white photographs are some of their precious possession with sentimental attachment. Those with means do go to Zanzibar once in a while. Others find it painful to pay a visit there, for it is no more the good old Zanzibar that they were associated with. Its Stone Town is haunting. The mosques, mehfils and jamaatkhana are desolate and bereft of the huge gathering that once filled the entire place. Your house glares longingly, you pass through those streets and gullies where you played and frequented in the past and some ghostly feeling creeps up, and in the still of the moment everything around there seems sad and bleak.

Some diasporans subjected to displacement still harbour grievances against the authority for the unfairness meted out to them. Their modest houses were confiscated. On the contrary today outsiders are welcomed and encouraged to put up mansions, hotels, and luxurious resorts under the guise of promoting tourism. They thrive and have their ways and means.

The present day Zanzibar is more of a tourist resort. Forodhani has undergone renovation, courtesy HH the Aga Khan, but its naturalness deformed. Its eateries mostly cater to the taste of tourists who flock there in the evenings. Zanzibaris swayed by the needs of tourists. Imagine nowadays they even sell curio stuff at Forodhani! Also every alternate shop on Portuguese Street deals in curios. The street has lost its old charm. It seems there are certain individuals behind the chain of business. Even their mode of salesmanship betrays the normal Zanzibari etiquette. The era of quality stuff, minimal margin and cordiality is forsaken to pave way for modern commercialism. The post-revolution phase has also given boost to Darajani/Ngambo trading mainly in garments and electronics. The business is again the monopoly of certain bigwigs who thrive through their overseas and mainland connections.

The indigenous Zanzibaris are God fearing, innocent and honest people. It is pity that the prevailing inflation snatches every penny of theirs. Zanzibar’s false economy and its political gimmickry is the feature of their day to day life.

In all honesty Afro-Shirazi Party (ASP) should have won the 1963 elections. Their share of votes was almost 55%. If the constituency representation had been apportioned in accordance with its denseness ASP would have emerged clear victor. Mind that the rapport between locals and us was remarkably good.

Our diaspora ( pre Revolution inhabitants and not those integrated of recent, also prior to the East African Railway settlers on the mainland) had a congenial environment with the adoption of the Afro Arab culture in its true sense.

To quote Professor Abdul Sheriff, in reply to Times of India’s Dilip Padgaonkar’s question, “What do you make of the Indian Government’s efforts to reach out to the Indian diaspora in Zanzibar?’ he put it beautifully:

“Feel for us. But please leave us alone; Zanzibar is our home, our past, our future.”

Talking of Zanzibar’s Khojas, they came in dhows to Zanzibarsince the mid nineteenth century (even earlier) and with the passage of time lost all the traces of their contacts in India. They were simple, peace loving and God fearing people. There was immense brotherhood among them and they cared for each other. Economically they were contented and mostly worked in Government offices where administration was excellent. Those who had business maintained only minimum margin of profit that resulted in high purchasing power and generally a good standard of living. They did not have the slightest inkling of such a revolution and were visibly shaken by it.

The past has flown fast and times have changed completely. The social, economic and political changes have had tremendous effect on our lives. It is exactly 50 years since that fateful day in Zanzibar. Sadly a large number has passed away. The anniversary has awakened poignant memory of the Zanzibardays. Today only a handful Khojas emanating from our Zanzibardiaspora remain in Zanzibar.