Marc Abrahams's Blog, page 62

January 12, 2022

Dramatic Improbable Readings for Arisia 2022

Improbable Research organizes a Dramatic Improbable Readings session at Arisia every year — dramatic readings from published research studies that make people laugh, then think.

In 2022, The Covid-19 pandemic led Arisia to cancel the 2022 convention. Undaunted, Improbable Research did and video recorded a new Dramatic Improbable Readings session. Marc Abrahams, editor of the Annals of Improbable Research, comperes. The dramatic readers are: Mason Porter, Sonya Taafe, Dean Grodzins, and Gary Dryfoos. Michele Liguori is the timekeeper. David Kessler is the deobfuscator.

January 11, 2022

“The Strange World of Breatharianism” documentary

“Breatharianism is a type of belief system started by Jasmuheen… that hypothesizes and claims to prove that humans can live without consuming solid foods…. She even received the Ig Nobel prize, a satirical parody of the true Nobel Prize, which means she joined the likes of L Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology and the new age guru Deepak Chopra.”

—So says the “Top Documentary Films” web site, describing the film “The Strange World of Breatharianism“.

The 2000 Ig Nobel Literature Prize was awarded to Jasmuheen (formerly known as Ellen Greve) of Australia, first lady of Breatharianism, for her book “Living on Light,” which explains that although some people do eat food, they don’t ever really need to.

January 6, 2022

Eva Wentink’s Self-Monitoring Toilet Musings

(Thanks to Michiel Scheffer for bringing this to our attention.)

January 4, 2022

What Does Slime Know?

“What Slime Knows” is an essay by Lacy M. Johnson, in Orion magazine:

Here in this little patch of mulch in my yard is a creature that begins life as a microscopic amoeba and ends it as a vibrant splotch that produces spores, and for all the time in between, it is a single cell that can grow as large as a bath mat, has no brain, no sense of sight or smell, but can solve mazes, learn patterns, keep time, and pass down the wisdom of generations….

Slime mold might not have evolved much in the past two billion years, but it has learned a few things….

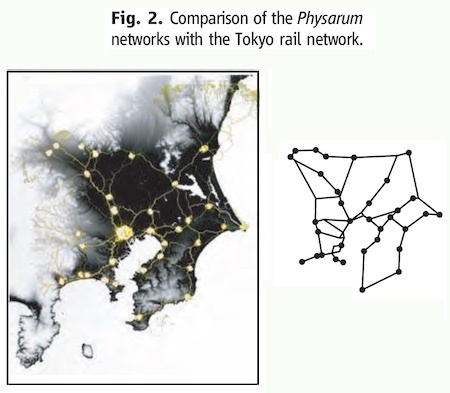

Some of the things that some of the slime molds have learned have resulted in Ig Nobel Prizes—two prizes so far—for the humans who took the trouble and time to notice, and themselves learn about, little bits of what the slime molds could do. The image you see here is from one of the prize-winning scientific reports.

January 3, 2022

Study Vampires, in Transylvania

Interested in ‘Vampires in Literature and Film’ and/or ‘Werewolves in Literature and Film’?

Interested in ‘Vampires in Literature and Film’ and/or ‘Werewolves in Literature and Film’?

If so, then where better to learn more about such things than Transylvania University (Lexington, KY, US) ?

Picture credit : The Vampire (1897) by Philip Burne-Jones

December 31, 2021

You Might Say Too Many Names for Too Many Numbers

“One problem with using nomenclature that gives credit to specific people is that you either create a winner-take-all situation or you create an ungainly string of names separated by hyphens. Also, if some hitherto unknown forerunner suddenly pops up, you suddenly have to change the name to acknowledge the newly discovered ‘winner’ “.

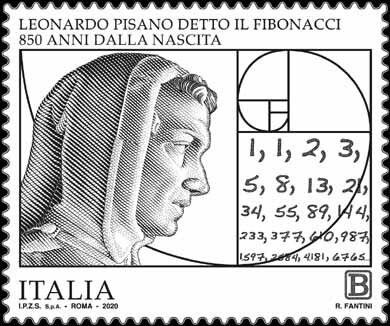

So writes mathematician Jim Propp. He begins his essay called “” by saying:

“I just went through my lesson plan for an upcoming lecture on number-sequences and replaced the name ‘Fibonacci’ by the name ‘Hemachandra’. By the time you finish reading this essay, you’ll know why I did it, and if you’re a teacher, I hope you’ll do it too….”

The drawing above depicts Hemachandra. The drawing below does not.

December 29, 2021

Klunk: Imperfect Synchrony in Animal Displays—Leadership?

Klunk and colleagues have, perhaps, taken the lead in assessing imperfect synchrony in animal displays. There is much to ponder in their new study:

“Imperfect Synchrony in Animal Displays: Why Does It Occur and What Is the True Role of Leadership?” Daniela M. Perez, Cristian L. Klunk, and Sabrina B.L. Araujo, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, vol. 376, no. 1835, October 2021, 20200339. (Thanks to Tony Tweedale for bringing this to our attention.) the authors, at Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brazil, report:

“Synchrony can be defined as the precise coordination between independent individuals, and this behaviour is more enigmatic when it is imperfect…. We studied imperfect courtship synchrony in fiddler crabs to mainly test whether (i) signal leadership and rate are defined by male quality and (ii) signal leadership generates synchrony. Fiddler crab males wave their enlarged claws during courtship, and females prefer leading males—displaying ahead of their neighbour(s). We filmed groups of waving males in the field to detect how often individuals were leaders and if they engaged in synchrony. Overall, we found that courtship effort is not directly related to male size, a general proxy for quality. Contrary to the long-standing assumption, we also revealed that leadership is not directly related to group synchrony, but faster wave rate correlates with both leadership and synchrony.”

BONUS: Here is a competing essay assessing imperfect synchrony: “The Weirdness of Watching Yourself on Zoom,” Sarah Dunphy-Lelii, Scientific American, August 1, 2020.

December 27, 2021

Hip-hop, Heavy metal, and 2D:4D ratios [BMJ Xmas issue]

The British Medical Journal (BMJ) has a tradition of publishing light-hearted and satirical fare (no spoofs, hoaxes, or fabricated studies) around the Christmas period. This year is no exception. Here’s a selection (all open-access) :

The greeting card image featured above is from : Bah humbug! Association between sending Christmas cards to trial participants and trial retention: randomised study within a trial conducted simultaneously across eight host trials

December 24, 2021

Tesla’s technology leaps slightly ahead of 1993 Ig Nobel Prize Winner

Reuters reports that automobile manufacturer Tesla added new technology to some of its cars, technology that goes slightly further even than the innovation that in 1993 won an Ig Nobel Prize for Michigan inventor Jay Schiffman. Reuters says:

The Visionary Technology Prize in 1993

WASHINGTON, Dec 8 (Reuters) – Expressing concern about distraction-affected vehicle crashes, the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) said on Wednesday it is discussing with Tesla Inc (TSLA.O) the electric carmaker’s software update that lets users play video games on a touch screen mounted in front of the dashboard.

Tesla added the games in an over-the-air software update sent to most of its vehicles this summer, the New York Times reported on Tuesday.

“Distraction-affected crashes are a concern, particularly in vehicles equipped with an array of convenience technologies such as entertainment screens. We are aware of driver concerns and are discussing the feature with the manufacturer,” NHTSA said in a statement provided to Reuters by email….

The 1993 Ig Nobel Prize for Visionary Technology was awarded jointly to Jay Schiffman of Farmington Hills, Michigan, inventor of AutoVision, an image projection device that makes it possible to drive a car and watch television at the same time, and to the Michigan state legislature, for making it legal to do so. Schiffman documented his technology, in US patent #5061996A.

Search for the Limits of Driver DistractionAn other Ig Nobel Prize, the 2011 Prize for Public Safety, was awarded for work that tried to identify the minimum amount of distraction that is dangerous for automobile drivers. That prize was given to John Senders of the University of Toronto, CANADA, for conducting a series of safety experiments in which a person drives an automobile on a major highway while a visor repeatedly flaps down over his face, blinding him.

Senders documented that research, in the study “The Attentional Demand of Automobile Driving,” John W. Senders, et al., Highway Research Record, vol. 195, 1967, pp. 15-33. You can see part of the research, in this television news report:

December 23, 2021

Two Ig Nobel laureates discuss “Research that makes people laugh and then think”

Hokkaido University published this discussion between two of its professors. (See the original article for additional photos.)

Two Ig Nobel laureates discuss “Research that makes people laugh and then think”Research News | December 23, 2021

Professor Toshiyuki Nakagaki (left), Research Institute for Electronic Science; Associate Professor Kazunori Yoshizawa (right), Research Faculty of Agriculture, Hokkaido University

The Ig Nobel Prize, established in 1991, is awarded to “research that makes people laugh and then think” and is also known as the “behind-the-scenes Nobel Prize.” This year, the online award ceremony was held on September 9 (Boston time, USA), and it was the 15th consecutive year that a Japanese researcher won the prize. Our university has two Ig Nobel Prize winners: Professor Toshiyuki Nakagaki of the Research Institute for Electronic Science, who won the Cognitive Science Prize in 2008 and the Transportation Planning Prize in 2010, and Associate Professor Kazunori Yoshizawa of the Research Faculty of Agriculture, who won the Biology Prize in 2017. The prize-winners, who have been researching “slime mold” and “barklice,” respectively—both of which are unknown to most people—discussed each other’s research and the environment of Hokkaido University.

Conveying the true joy of science through unexpectedly funny researchYoshizawa: You have won the Ig Nobel Prize twice. What was it like when you won the first one?

Nakagaki: The Ig Nobel Prize is a parody of the Nobel Prize, so when I went to the first award ceremony, I thought the mood would be more chilly. I thought I would be the target of ridicule. But it was a very fun ceremony full of all kinds of tricks and little stories.

Yoshizawa: I wasn’t able to attend the ceremony when I was awarded, but I felt that way when I watched the broadcast of the ceremony. They used the Nobel Prize and the authority itself as a laughing stock.

Nakagaki: The spirit of the prize is to make people laugh and then make them think, isn’t it? In addition to conveying the true joy of science to the world through research, people also laugh when they see something truly unexpected.

Yoshizawa: Researchers, including us, are extremely serious, and that’s why it’s so interesting.

Discovery of Insects with Male and Female Sex Organs ReversedNakagaki: Mr. Yoshizawa, you won an award for your research on a new insect species in which the male has a vagina, and the female has a penis.

Yoshizawa: Reproduction is a competition between sexes to maximize benefit. The insect I studied, a genus of barklice called Neotrogla, lives in a very nutrient-poor cave in Brazil, so the semen of the male is a valuable source of nutrition for the female. So the female has evolved to have a switching valve to increase the amount of semen receiving ports to two, so that it can receive twice as much semen. And the female penis evolved as a structure to actively receive semen from males.

Nakagaki: That’s interesting; semen is required as nutrition.

Yoshizawa: During mating, the female inserts her penis into the male’s body and sucks out the sperm and nutrition. There is a fierce struggle between the male and female, like, “Give me the semen!” “No, I won’t do it so easily!” (laughs)

Nakagaki: So it’s the opposite of ordinary creatures.

Yoshizawa: My current guess is that females came to have penises as the power relationship during mating was reversed.

Nakagaki: Just by talking about it, it changes the way we look at males and females. I think it’s research that makes us fundamentally reconsider the evolution of males and females.

Demonstrating the cleverness of slime mold, a single-celled organism that solves mazesYoshizawa: Your paper was published in Nature, wasn’t it? I happened to be flipping through the magazine, and the moment I saw a photo of slime mold solving a maze, I immediately thought, “This is interesting!” Even if you don’t understand the logic, you can intuitively understand the essence of the research.

Nakagaki: Originally, I was studying the behavior of single-celled organisms, and I was always thinking about how to show their performance in an easy-to-understand way. For my research, I kept a true slime mold called “mozihokori” or “the blob” (Physarum polycephalum) and fed it oatmeal. And I tried placing the food far away, putting obstacles in the way, and creating situations that would be difficult for the slime mold.

Yoshizawa: Did it avoid the obstacles to move forward?

Nakagaki: Yes. When it hit a dead end, it went back. Then I thought it would be a good experiment to do this in a maze.

Yoshizawa: Your second award was for your research on transportation networks using slime mold.

Nakagaki: When I increased the number of feeding sites to seven, I thought it would be interesting to try this on a map. Based on a map of the Tokyo metropolitan area, I placed devices that slime mold dislikes in places where it is difficult to set up a transportation network. Then, it would find an efficient route while avoiding those places. We thought this could be applied to the design of transportation infrastructure in society.

Yoshizawa: When you put it side by side with the actual traffic network, you can clearly see the similarity. I was very impressed with this brilliant demonstration.

Yoshizawa: As a researcher, what I find is that—even if you are looking at the same thing—the way you see it is completely different depending on the person. For example, small differences in small insects are immediately apparent to me.

Nakagaki: Yes, yes! It’s interesting that the way you see things changes depending on your knowledge and experience. It’s like training your observational eyes and sensitivity.

Yoshizawa: Nowadays, people are using genome data to estimate the phylogenetic evolution of insects, and it is generally thought that this phylogeny is the most accurate. However, from the perspective of a researcher focusing on the shape of living things, there is a part of me that says, “That’s not true. I want to go against the trend and keep focusing on the shape.”

Nakagaki: It’s important to observe carefully first. I want students to see a lot of real things.

Yoshizawa: In that sense, fieldwork is also necessary. There are things you can’t see unless you’re in the actual environment.

Nakagaki: In that respect, Hokkaido University is good. You can do fieldwork right on campus. (laughs)

The field where you can do what you really want to doYoshizawa: Don’t you think that you are often asked, “How can your research help the world?”

Nakagaki: That’s true. When reporters write an article, I think it would be easier for readers to understand if they conclude with that point.

Yoshizawa: However, I would like to say out loud that basic research, like what we are doing, research that seems “useless” at first glance, is actually important. Really important.

Nakagaki: It is the role of science to stimulate intellectual curiosity, not just to provide concrete benefits to the world.

Yoshizawa: I thought that the point of the Ig Nobel Prize is how interesting the researcher makes the research, and I thought my research was too straightforward.

Nakagaki: I think my research is also too straightforward, but I hear that all the Ig Nobel winners say the same. (laughs)

Yoshizawa: I think the fact that we can do research that could win an Ig Nobel Prize shows the diversity and breadth of the academic field at Hokkaido University. A very simple discipline like insect taxonomy has survived for over 100 years.

Nakagaki: That’s really true. I want to welcome people who have a passionate desire to study something to Hokkaido University.

Yoshizawa: Let’s hope that the future winners will follow in our footsteps. (laughs)

This article was originally published in Japanese in the Hokkaido University brochure Be Ambitious .

Related Link:

Research for Laughter, Research for Thinking

Ig Nobels come together at Hokkaido university

Marc Abrahams's Blog

- Marc Abrahams's profile

- 14 followers