Marc Abrahams's Blog, page 264

June 22, 2016

Eat Powdered Mummies for Good Health [podcast 69]

Nowadays, powdered mummy may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but for many years it was just what the doctor ordered, as you will hear in this week’s Improbable Research podcast.

SUBSCRIBE on Play.it, iTunes, or Spotify to get a new episode every week, free.

This week, Marc Abrahams — with dramatic readings by Daniel Rosenberg — tells about:

Powdered mummy — ‘“Good Physic but Bad Food”: Early Modern Attitudes to Medicinal Cannibalism and its Suppliers,’ Richard Sugg, Social History of Medicine, vol. 19, no. 2, 2006, pp. 225–40. Here’s a photo of a not-yet-powdered mummy in The British Museum:

The mysterious John Schedler or the shadowy Bruce Petschek perhaps did the sound engineering this week.

The Improbable Research podcast is all about research that makes people LAUGH, then THINK — real research, about anything and everything, from everywhere —research that may be good or bad, important or trivial, valuable or worthless. CBS distributes it, on the CBS Play.it web site, and on iTunes and Spotify).

June 21, 2016

The Journal of Interrupted [something]

The Journal of Interrupted Studies, which also seems to call itself the Journal of Interrupted Science, is a proposed publication for scholars who have suffered interruptions in their lives and careers.

An article in the Oxford Student explains:

Coffee seems to be Paul Ostwald’s preferred editorial tool when it comes to The Journal of Interrupted Studies, an Oxford-based academic journal that will publish the complete and incomplete scholarly works of academics whose work has been interrupted by forced migration. The idea for this new scholarly review was born over a cup (or more) with Paul’s flatmate and co-editor Mark Barclay. Subsequent team members, including Geri della Rocca de Candal, the Journal’s academic editor, have also undergone induction in the Missing Bean, where Paul and I first meet to discuss the project….

The Journal’s immediate aim is to give refugee academics a platform that is usually prohibited by the conditions of their immigrant status, but also by the Anglophone and Eurocentric bias of the academic publishing industry.

Renee Montagne interviewed editor Ostwald, on NPR’s Morning Edition program:

MONTAGNE: You know, the human stories behind these, too, though, are that these people, in many cases – what? – don’t have access to what they need to complete their work or to have it published?

OSTWALD: Exactly. So what we get a lot are articles where you can just see the lines of interruption running through the pages, really, where you can see someone couldn’t complete his research, someone couldn’t read further into the subject. And what we try to do in those cases is provide them with literature and PDF articles that can be viewed on a smart phone and try and really, you know, enable them to continue their studies as much as we can, really. But we’re also very open to publish non-completed articles, which is quite uncommon. But basically, what we do is we say, well, listen, you know, this article can’t be completed right now, but we hope it will be in the future.

(Thanks to Scott Langill for bringing this to our attention.)

Short Paper Titles Tend to Have a Longer Reach

A study with a six-word-long title tells about the effects of study title lengths:

“The Advantage of Short Paper Titles,” Adrian Letchford, Helen Susannah Moat, Tobias Preis, Royal Society Open Science, epub August 26, 2015. The authors, at the University of Warwick, UK, report:

“Vast numbers of scientific articles are published each year, some of which attract considerable attention, and some of which go almost unnoticed. Here, we investigate whether any of this variance can be explained by a simple metric of one aspect of the paper’s presentation: the length of its title. Our analysis provides evidence that journals which publish papers with shorter titles receive more citations per paper. These results are consistent with the intriguing hypothesis that papers with shorter titles may be easier to understand, and hence attract more citations.”

Karen Hopkin talks about this, tersely, in this video for Scientific American:

BONUS: The Ig Nobel Prize-winning (literature prize, 2006) paper “Consequences of Erudite Vernacular Utilized Irrespective of Necessity: Problems with Using Long Words Needlessly.”

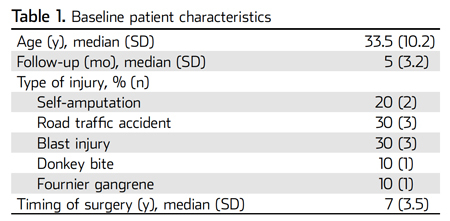

Incomplete info: The case of the donkey-bitten member

Some published medical reports give incomplete information, inducing frustration in intellectually curious readers. This newly published study exemplifies the problem:

“Total Phallic Reconstruction Using the Radial Artery Based Forearm Free Flap After Traumatic Penile Amputation,” Marco Falcone, MD, Giulio Garaffa, MD, PhD, FRCS(Eng), Amr Raheem, MD, Nim A. Christopher, MPhil, FRCS(Urol), and David J. Ralph, FRCS(Urol), Journal of Sexual Medicine, vol. 13, 2016, pp. 1119-1124. The authors, at University College London Hospitals, UK, the University of Turin, Italy, and the University of Cairo, Egypt, report:

“The causes of penile loss were self-amputation owing to an acute schizophrenic episode (n = 2), road traffic accident (n = 3), blast injury (n = 3), donkey bite (n = 1), and Fournier gangrene (n = 1).”

Here is further detail from the study:

The study includes no further information about the donkey.

June 20, 2016

Overturned rhinoceros beetles – how do they get back on their feet? (study)

No matter how careful a beetle might be, there’s a fair chance that, sooner or later, it’ll find itself on its back. Raising the question, how does it right itself, i.e. get onto its feet again?

For current beetle-righting research turn to volume 28, Issue 2, 2016, of the journal Ecological Psychology where researchers professor Masato Sasaki and professor Tetsushi Nonaka [respectively of the Graduate School of Education, University of Tokyo and the Graduate School of Human Development and Environment, Kobe University, Japan] describe a set of experiments designed to provide some answers.

Beetles (more specifically Japanese rhinoceros beetles, Allomyrina dichotomus) were upturned on a variety of surfaces :

1. A trench in the floor,

2. A towel,

3. A fan,

4. A pan mat,

5. A sheet of newspaper,

6. A wooden toothpick,

7. A narrow ribbon,

8. A wide ribbon,

9. A plastic string,

10. A sheet of tissue paper,

11. A T-shirt,

12. A perilla leaf,

13. A sheet of scratch paper,

14. A disposable chopstick, and

15. The lid of a film case.

– to try and determine how they’d get the right way up again. Depending on the surface, the team noted various strategies and degrees of success (or otherwise). Here is the description for the Towel trial #2 (one of the more successful trials, as shown above).

“When the insect was turned upside down, a towel was slid on the floor to the left side of the beetle’s head. As the towel approached, the beetle oriented its head to it immediately and the two hind legs started to move in-phase, which resulted in the locomotion by pushing with the hind legs. The approach of a towel slipping over the wooden substrate surface may have shaded the part of optic array surrounding the beetle, or changed the air flow that could be sensed by its antennae, which seems to have induced the prospective extension of the leg on that side. Shortly after, the left foreleg came close to the towel and briefly touched it, and the left foreleg got entangled with the towel. Using this leg as a pivot point, the beetle pulled the whole body in such a way to roll. Subsequently, the tips of the right middle and hind legs also grasped the towel and the insect succeeded in righting itself. The leg of the insect was observed to release the cloth, which had been tangled tightly. However, how this was made possible is unclear. Duration: 3 s.”

The team came to various conclusions [for details see the full paper, linked above] not least that :

“It is not improbable that various meanings of the habitat of an animal are embodied and embedded in the tips of the body-like claws.”

Note: After the experiments, the beetles were released back into the wild, where several promptly fell over again – but managed to quickly right themselves.

“This observation suggested that, in their natural habitat, it is not so difficult for beetles to right themselves after having been turned upside down.”

Also see: Geometry and self-righting of turtles and A Review of Self-Righting Techniques for Terrestrial Animals

June 19, 2016

Cheers for the Oxford Offal Conference

You can be part of the cheering throngs at the Oxford Offal Conference, which will befall 8-10 July at the University of Oxford.

The Offal Conference is this year’s incarnation of the Oxford Symposium of Food and Cookery. On the menu, both intellectually and sur table: offal, offal, and more offal. What is offal, you may slightly wonder? Here’s the official Offal Conference take on offal:

Offal can mean many things. It does not just refer to organ meats but to the manifold ways in which certain foods may be rejected and despised (‘awful offal’!); or reclaimed and loved. There can be vegetable offal, in the form of the ‘ugly’ vegetables deemed too imperfect for supermarkets to sell. We invite papers that embrace the subject of offal from a wide and imaginative perspective.

Conference attendees will be ingest offal. The conference web site touts, in advance, some of those rendered remains:

Friday Night Feast: Fergus Henderson, the King of Nose-to-Tail Cookery [will prepare] A Bold Offal Feast ( and Bold Vegetables).

Saturday Lunch will be all vegetable, titled Leftover, Rejected, Orphaned, and Reclaimed.

Saturday Dinner: Jacob Kenedy of Bocca di Lupo restaurant in London… will be cooking A Roman Offal Feast including vegetable and fish offal.

At least two of our colleagues will contribute to the offalness:

Saturday morning panel discussion: What is offal? What does it mean in different cultures? Why is it sometimes a delicacy and sometimes a source of horror? What are some of the common features of offal cookery? … Joining the panel: Merry White , anthropologist of Japanese food and author of the legendary Cooking for Crowds as well as, more recently, Coffee Life in Japan (UC Press).

On Sunday, our plenary speaker is Ben Wurgaft , addressing the subject of In Vitro Meat: the science and philosophy of ‘lab meat’.

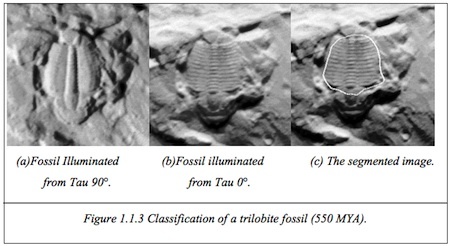

A rare Ph.D. thesis with a trilobite and tribology

This is one of the very few doctoral these that explicitly deal with both a trilobite (the extinct animal) and tribology (the study of how surfaces rub against each other or don’t):

“The classification of textured surfaces under varying illuminant direction,” Ged McGunnigle, PhD dissertation, Heriot-Watt University, June 1998. The author writes:

“This thesis sets texture analysis in a physical context…. The first component is the rough surface, models of the surface topography are selected from the fields of tribology and scattering….

“We illustrate the importance of illuminant direction for rough surface discrimination with the following example. Consider the fossilised trilobite (Elrathia Kingii, 550 MYA, Utah) shown in Figure 1.1.3a. Here the fossil is illuminated from tau=90° and there is little texture information that can be used to segment the fossil from the surrounding matrix.”

June 18, 2016

This and that about drawing a perfect circle

There’s much to be said and done about drawing perfect circles. Alexander Overwijk says and does some of it, in this video:

Stephen Ornes says lots more, in the essay “Archimedes in the Fence“, in The Last Word on Nothing”.

June 17, 2016

Introducing the newly patented Wheelbarrow-Chair (and vice versa)

Do you sometimes wish you had a wheelbarrow that could convert into a chair? Or a chair that could convert into a wheelbarrow? You’re luck could be in.

Inventors James Patrick Cardona, of Coolum Beach, Queensland (Australia); Trevor Raymond Clark, of Woombye, Queensland (Australia); Guy Darren Trappett, of Peregian Spring, Queensland (Australia); and Mario Cardona, of Coolum Beach, Queensland (Australia) . . .

– have just (March 29, 2016) received their US patent for a ‘Convertible dual purpose device’.

– have just (March 29, 2016) received their US patent for a ‘Convertible dual purpose device’.

Also see: Another new patent (May 2016) – A shovel that’s also an umbrella, or an umbrella that’s also a shovel.

June 16, 2016

Much Ado About Very Little: Angry Everything, Practically [Angry Birds]

A newly published study challenges the often-angry claim that video games make kids more violent. The study is:

“Angry Birds, Angry Children, and Angry Meta-Analysts: A Reanalysis,” Luis Furuya-Kanamori [pictured here] and Suhail A. R. Doi, Perspectives on Psychological Science, vol. 11, no. 3, May 2016, pp. 408-414. (Thanks to Neil Martin for bringing this to our attention.) The authors, at Australian National University, explain:

“Angry Birds, Angry Children, and Angry Meta-Analysts: A Reanalysis,” Luis Furuya-Kanamori [pictured here] and Suhail A. R. Doi, Perspectives on Psychological Science, vol. 11, no. 3, May 2016, pp. 408-414. (Thanks to Neil Martin for bringing this to our attention.) The authors, at Australian National University, explain:

“As suggested by Markey (2015), we reanalyzed the data without a preconceived opinion about the effects of video games on children mental health. We found a very small effect size for the association of video games and aggressive behavior… We are quite confident that our results accurately demonstrate that violent and general video games exposure has a statistically significant, yet very small, effect size associated with aggression in children that in effect could represent no association.”

Marc Abrahams's Blog

- Marc Abrahams's profile

- 14 followers