Marc Abrahams's Blog, page 237

December 4, 2016

Words can possibly have meanings

We have been advised that this published study possibly says something:

“Contesting Essentialist Theories of Patriarchal Relations: Evolutionary Psychology and the Denial of History,” by Jesse Crane-Seeber and Betsy Crane [pictured here], The Journal of Men’s Studies, October 2010, vol. 18, no. 3, 218-237. The authors, at Widener University, write:

“This essay emerges from an ongoing mother-son dialogue about contemporary gender relations and their genesis in the history of patriarchy. In order to reframe patriarchy as a relational construct, rather than a simple group-based oppression, a performative notion of identities grounds the paper. It offers a critique of the body of literature that has developed under the broad heading of “evolutionary psychology,” insisting that gendered relations are not outcomes of genetic selection, divine mandate, or historical inevitability. An antidotal, millennia-spanning history of gender is offered as an epistemically and politically preferable explanation for patriarchal relations.”

(Thanks to Ilse Weil for bringing this to our attention.)

NEXT POST: Dirty, dirty money?

December 3, 2016

Robert Sapolsky: How a Chair Revealed the Type A Personality Profile

Robert Sapolsky explains how several apparently unrelated things — most especially a chair — led to new understanding about why certain kinds of people were suffering certain kinds of medical problems:

(Thanks to Joanne Manaster for bringing this to our attention.)

NEXT POST: Can words have meanings?

December 2, 2016

The man who wants you to realize that reality is unrealistic

A professor cooks up some computer simulations, which convince him to try to convince everyone that reality is unrealistic. Amanda Gefter interviewed the professor, for The Atlantic magazine: “The Case Against Reality“.

NEXT POST: Type A personality from a chair?

Chimps Recognize Butts That Are Upside-Down, Too

A new study builds on prize-winning do-chimps-recognize-buttocks research, adding an upside-down appraisal:

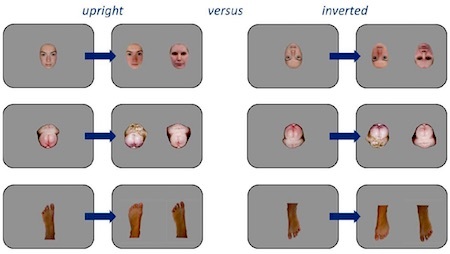

“Getting to the Bottom of Face Processing. Species-Specific Inversion Effects for Faces and Behinds in Humans and Chimpanzees (Pan Troglodytes),” Mariska E. Kret and Masaki Tomonaga, PLOS ONE, November 30, 2016. The authors, at Leiden University, the Netherlands, and Kyoto University, Japan, build on work, by other researchers, that won an Ig Nobel Anatomy Prize:

“In four different delayed matching-to-sample tasks with upright and inverted body parts, we show that humans demonstrate a face, but not a behind inversion effect and that chimpanzees show a behind, but no clear face inversion effect. The findings suggest an evolutionary shift in socio-sexual signalling function from behinds to faces, two hairless, symmetrical and attractive body parts.”

Leiden University issued a press release that gives further colorful details.

The 2012 Ig Nobel Prize for anatomy was awarded to Frans de Waal and Jennifer Pokorny, for discovering that chimpanzees can identify other chimpanzees individually from seeing photographs of their rear ends. They describe that research, in the study “Faces and Behinds: Chimpanzee Sex Perception“, Frans B.M. de Waal and Jennifer J. Pokorny, Advanced Science Letters, vol. 1, 2008, pp. 99–103.

Frans de Waal was pleased to see his Ig Nobel-winning research confirmed by this new study, he told the Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant: ‘Ik ben blij dat deze nieuwe studie dat bevestigt‘.

NEXT POST: Is reality really unreal?

A tradeoff that comes with romantic dating

Ig Nobel Prize winner Dan Ariely muses on a tradeoff that comes with romantic dating:

Dan Ariely often wonders at the simultaneous existence of reality and the illusions that come with and modify that reality. The 2008 Ig Nobel Prize for medicine was awarded to Dan Ariely, Rebecca L. Waber, Baba Shivof, and Ziv Carmon for demonstrating that high-priced fake medicine is more effective than low-priced fake medicine. (That research is documented in the study “Commercial Features of Placebo and Therapeutic Efficacy,” Rebecca L. Waber; Baba Shiv; Ziv Carmon; Dan Ariely, Journal of the American Medical Association, March 5, 2008; 299: 1016-1017.)

NEXT POST: Upside-down chimp-butt appraisal?

December 1, 2016

Computer games: Should they be taken seriously or unseriously?

That can depend, to quite a degree, upon whom you ask.

“A serious game is a name given to computer software that tries to achieve just that. While some people think that serious games and games for learning are synonymous, digital games can be used for ‘serious’ purposes other than learning. Serious games can be used for motivating people to exercise more. Serious games can be used for medical treatment. Serious games can be used as a marketing tool. These are just a few examples, and we will illustrate various application areas with many actual serious games in this book.”

The book in question is ‘Serious Games : Foundations, Concepts and Practice’ – Eds. Ralf Dörner, Stefan Göbel, Wolfgang Effelsberg, Josef Wiemeyer, Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016.

On the other hand, explains Professor Bart Simon [pictured right] of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada,

“

This article initiates a provocation for a collective discussion of what we might call an unserious epistemology for the study and design of games. How can we find ways of taking the unseriousness of games seriously? Starting with the idea that most players take their games much less seriously than game studies scholars, I reflect on the importance of the idea of unseriousness for the theorization of gameplay as a sociocultural activity of last resort in a contemporary world defined by the grave seriousness of life.”

See: ‘Unserious’ in the ludological journal Games and Culture, September, 2016.

NEXT POST: Is there anything wrong with romantic dating?

November 30, 2016

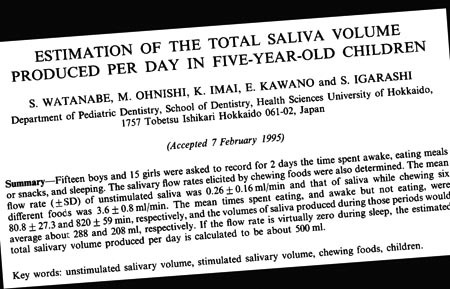

How much saliva does a five-year-old kid produce? (podcast #92)

How do you measure how much saliva a five-year-old kid produces in a day? A Japanese study describes one approach, and we go with that flow (to an extent), in this week’s Improbable Research podcast.

SUBSCRIBE on Play.it, iTunes, or Spotify to get a new episode every week, free.

This week, Marc Abrahams discusses a published saliva-filled study, with dramatic readings from Nicole Sharp, creator of FYFD, the internet’s most popular site about fluid dynamics. (She also does research on the Boston Molasses Flood.)

For more info about what we discuss this week, go explore:

“Estimation of the Total Saliva Volume Produced Per Day in Five-Year-Old Children,” S. Watanabe, M. Ohnishi, K. Imai, E. Kawano, and S. Igarashi, Archives of Oral Biology, vol. 40, no. 8, August 1995, pp. 781-782.

Saliva.

The mysterious John Schedler or the shadowy Bruce Petschek perhaps did the sound engineering this week.

The Improbable Research podcast is all about research that makes people LAUGH, then THINK — real research, about anything and everything, from everywhere —research that may be good or bad, important or trivial, valuable or worthless. CBS distributes it, on the CBS Play.it web site, and on iTunes and Spotify).

NEXT POST: Game, seriously?

November 29, 2016

Can’t not eat money, maybe

The saying “We can’t eat money” begs disagreement from British vegans and vegetarians. A report in The Guardian says:

Bank of England urged to make new £5 note vegan-friendly

More than 50,000 sign petition to cease use of tallow in production process, saying it is unacceptable to vegans and vegetarians…

NEXT BLOG POST: Did those kids drool way too much?

Earliest reported human flight in Britain (some time near the year 1000)

The earliest reported human flight in Britain happened, if it happened, long. long ago. Alison Hudson reports, in the British Library’s Medieval Manuscripts blog:

It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane, It’s a… Monk?

…did you know that the first recorded pioneer of man-powered flight in the British Isles was an Anglo-Saxon monk from Malmesbury Abbey called Eilmer (or in Old English, Æthelmaer) who lived between about 980 and 1070?

Eilmer’s life is recounted in the Deeds of the Kings of England [pictured here] by William of Malmesbury; indeed, William may have met him when Eilmer was an old man. According to William, many years earlier Eilmer had attached wings to his hands and his feet and jumped from a tower, travelling at least a ‘stadium’ (possibly 200 metres or 600 feet), before being caught by turbulence and breaking both his legs. Eilmer later claimed his error was not fitting a tail to himself, as well as wings. For comparison, the Wright Brothers’ first flight covered about 120 feet.

Eilmer was probably born in the 980s and died after 1066, so his flight probably took place in the 1000s or 1010s. We can guess Eilmer’s lifespan because William of Malmesbury claimed Eilmer had seen Halley’s Comet twice, in 1066 and presumably in 989….

The text, which you can read translated into modern English at archive.org, says:

He was a man of good learning for those times, of mature age, and in his early youth had hazarded an attempt of singular temerity. He had by some contrivance fastened wings to his hands and feet, in order that, looking upon the fable as true, he might fly like Daedalus, and collecting the air on the summit of a tower, had flown for more than the distance of a furlong; but, agitated by the violence of the wind and the current of air, as well as by the consciousness of his rash attempt, he fell and broke his legs, and was lame ever after. He used to relate as the cause of his failure, his forgetting to provide himself a tail.

NEXT BLOG POST: Why do they fear British money is made of meat?

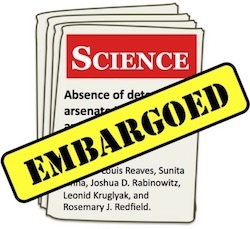

A blockade on embargoes, to loose the flood of hidden science news?

“If journalists stopped believing they had to publish a story or post a blog the minute a new study came out…”

You will never hear about most of the flood of research that’s done, worldwide. Partly, that’s because there is so very, very much of it.  But partly, it’s because the custom of “embargoing” a small number of studies ends up focusing most press attention — and so most public attention — on a teeny tiny, itsy bitsy fraction of what’s out there.

But partly, it’s because the custom of “embargoing” a small number of studies ends up focusing most press attention — and so most public attention — on a teeny tiny, itsy bitsy fraction of what’s out there.

Ivan Oransky tells how this works, and how it came to be, in an article in Vox: “Why science news embargoes are bad for the public“. Here’s part of that:

… But it’s clear that a lot of the power of embargoes would go away if journalists stopped believing they had to publish a story or post a blog the minute a new study came out. Sure, I get the value of a news peg. I used to run a wire service, Reuters Health, that covers health. But it warps the public’s understanding of how science works.

One new study can’t overturn the consensus in the field. And in many cases, the newest study is just the one most likely to be disproven in the future. Readers can often learn more from the history of a scientific question than they can from just the latest stab at answering that question.

But because reporters feel the need to make every finding sound important, embargoes are responsible in some large part, for example, for the weekly seesaw of “coffee is good for you, coffee is bad for you” news coverage with which we’ve all become too familiar….

BONUS: If you want to see some research that’s way outside the it-must-be-important-because-it’s-embargoed research, dip into the Annals of Improbable Research from time to time.

NEXT BLOG POST: Did a British monk flap his wings 1000 years ago?

Marc Abrahams's Blog

- Marc Abrahams's profile

- 14 followers