Marc Abrahams's Blog, page 227

February 26, 2017

The Scottish Wasabi Fire Alarm

The National Museum of Scotland includes in its vast collection this item, number T.2012.28:

DescriptionFire alarm for waking deaf people by nasal irritation with synthesized wasabi, awarded 2011 Ig Nobel prize in chemistry, designed by Makoto Imai, Naoki Urushihata, Hideki Tanemura, Yukinobu Tajima, Hideaki Goto, Koichiro Mizoguchi and Junichi Murakami, Japan, 2012

Inventor Makoto Imai himself donated this item to the museum, in Edinburgh, during the 2012 Ig Nobel EuroTour.

February 25, 2017

With enough data, you can figure out any problem, maybe

Throw enough data at a problem, and you will find the answer, perhaps, or maybe, or possibly. That general approach fuels much optimism, research, and financial investment. Jeneen Interlandi explores part of the notion, in an article called “The Paradox of Precision Medicine,” in the April 2016 issue of Scientific American:

Precision medicine sounds like an inarguably good thing. It begins with the observation that individuals vary in their genetic makeup and that their diseases and responses to medications differ as a result. It then aims to find the right drug, for the right patient, at the right time, every time….

Ask scientists who favor precision medicine for an example of what it might accomplish, and they are likely to tell you about ivacaftor, a new drug that has eased symptoms in a small and very specific subset of patients with cystic fibrosis…

But ask opponents for an example of why precision medicine is fatally flawed, and they, too, are likely to tell you about ivacaftor….

If [scientists were able to gather a diverse and huge enough amount of data, and compare it] among as many individuals as possible, they would finally be able to pinpoint which constellation of forces drive which diseases, how best to identify those forces and how to devise treatments that target them….

Scientists learn more every day about the distinct forces that interact to produce disease in individuals. It is natural and fitting that they should start putting that information together in a systematic way. But society should not expect such efforts to completely transform medicine any time soon.

xx

February 23, 2017

Is it a Mug or Cup? Recent Progress in Fuzziness Studies

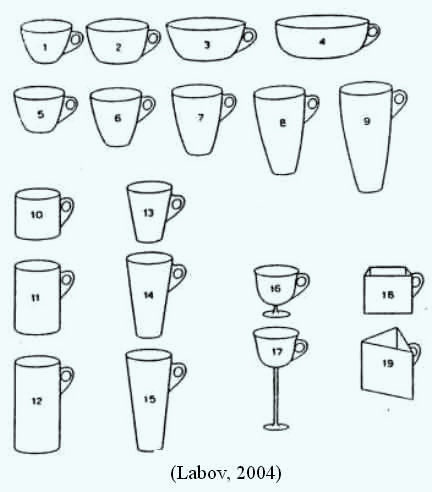

Where does a cup end and a mug start? And vice versa? Help towards answering this consistently vexing question can be found in an essay by Brett Laybutt entitled A Corpus Study of ‘Cup of [Tea]’ and ‘Mug of [Tea]’ In which he cites the work of scholars who have tried, over the years, to crack its complexities – e.g. the work of Professor William Labov of the University of Pennsylvania.

“One of the first, and most influential, was Labov‟s (2004) original 1975 experiment in which subjects were shown pictures of varying indeterminacy and asked to label them.”

“From this, Labov was able to come up with a mathematical definition of ‘cup’. ”

Further reading : Labov, W. (2004). “The Boundaries of Words and their Meanings”. In B. Aarts, D. Denison, E. Keizer, & G. Popova (Eds.), Fuzzy Grammar: A Reader. Currently available at £185 from Oxford University Press.

Coming soon : How much water is in a cup of tea?

February 21, 2017

Sighing: Neurobiologists hasten to catch up with psychologists

Psychologists, having been decorated (see below) for pursuing insights about why people sigh, now see neurobiologists tailing after them.

A press release earlier this year from UCLA announces: “UCLA and Stanford researchers pinpoint origin of sighing reflex in the brain“. The press release also contains a body of text, which contains this explanation: “Sighing appears to be regulated by the fewest number of neurons we have seen linked to a fundamental human behavior,” explained Jack Feldman, a professor of neurobiology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and a member of the UCLA Brain Research Institute. “One of the holy grails in neuroscience is figuring out how the brain controls behavior. Our finding gives us insights into mechanisms that may underlie much more complex behaviors.” Details are in a study published in the journal Nature, called “The peptidergic control circuit for sighing”, by Peng Li, Wiktor A. Janczewski, Kevin Yackle, Kaiwen Kam, Silvia Pagliardini, Mark A. Krasnow and Jack L. Feldman.

The 2011 Ig Nobel Prize for psychology was awarded to Karl Halvor Teigen [pictured here] of the University of Oslo, for trying to understand why, in everyday life, people sigh. (Teigen published details in the paper “Is a Sigh ‘Just a Sigh’? — Sighs as Emotional Signals and Responses to a Difficult Task,” Karl Halvor Teigen, Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, vol. 49, no. 1, 2008, pp. 49–57.)

The 2011 Ig Nobel Prize for psychology was awarded to Karl Halvor Teigen [pictured here] of the University of Oslo, for trying to understand why, in everyday life, people sigh. (Teigen published details in the paper “Is a Sigh ‘Just a Sigh’? — Sighs as Emotional Signals and Responses to a Difficult Task,” Karl Halvor Teigen, Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, vol. 49, no. 1, 2008, pp. 49–57.)

February 20, 2017

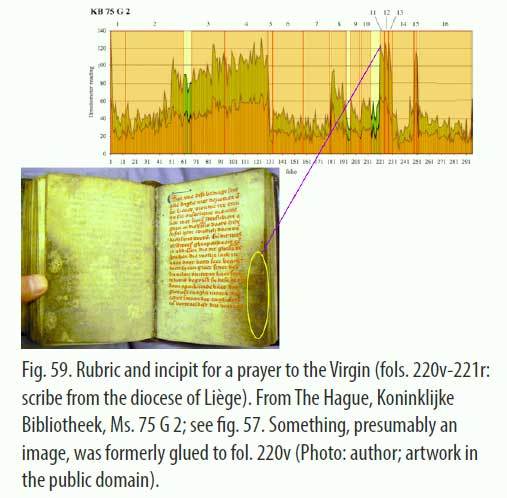

Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer

“The dirt ground into the margins of medieval manuscripts is one of their interpretable features, which can help us to understand the desires, fears, and reading habits of the past.”

– explains researcher Dr Kathryn M. Rudy who is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Art History, of the University of St Andrews, Scotland. She points out, however, that :-

“Cleaning or trimming the dirt from them is tantamount to discarding a provocative cultural witness.“

Dr Rudy proposes instead the use of a densitometer – a machine that measures the darkness of a reflecting surface and which can reveal which texts a reader favoured, but without damaging the dirt.

See: Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer in the Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art. Volume 2, Issue 1-2 (Summer 2010).

February 19, 2017

He smells

One of NASA’s best noses got a good writeup in 2003, in an official bulletin called “NASA’s Nose: Avoiding smelly situations in space“:

Thanks to George Aldrich and his team of NASA sniffers, astronauts can breathe a little bit easier. Aldrich is a chemical specialist or “chief sniffer” at the White Sands Test Facility’s Molecular Desorption and Analysis Laboratory in New Mexico. His job is to smell items before they can be flown in the space shuttle.

Aldrich explained that smells change in space and that once astronauts are up there, they’re stuck with whatever smells are onboard with them. In space, astronauts aren’t able to open the window for extra ventilation, Aldrich said.

The Know I Know web site, too, recently took a look at the smelling situation.

(Thanks to Scott Langill for bringing this to our attention.)

February 18, 2017

Many women have men in the brain

The old saying that a woman has “men on the brain” can be accurately supplanted by saying that many women have men IN the brain. This study explains the biological facts:

“Male microchimerism in the human female brain,” William F.N. Chan, Cecile Gurnot, Thomas J. Montine, Joshua A. Sonnen, Katherine A. Guthrie [pictured here], and J. Lee Nelson, PLoS One, vol. 7, no. 9, 2012, e45592. the authors, at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, and at the University of Washington, report:

“Male microchimerism in the human female brain,” William F.N. Chan, Cecile Gurnot, Thomas J. Montine, Joshua A. Sonnen, Katherine A. Guthrie [pictured here], and J. Lee Nelson, PLoS One, vol. 7, no. 9, 2012, e45592. the authors, at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, and at the University of Washington, report:

“In this study, we quantified male DNA in the human female brain as a marker for microchimerism of fetal origin (i.e. acquisition of male DNA by a woman while bearing a male fetus)…. We report that 63% of the females (37 of 59) tested harbored male microchimerism in the brain. Male microchimerism was present in multiple brain regions…. In conclusion, male microchimerism is frequent and widely distributed in the human female brain.”

BONUS: The 2005 study “Male microchimerism in women without sons: quantitative assessment and correlation with pregnancy history,” which says: “Male microchimerism was not infrequent in women without sons.”

BONUS [only distantly related]: One of the studies honored by the 2015 Ig Nobel Medicine Prize reports how male DNA, obtained via a lengthy, intimate kiss, can sometimes be found in the saliva of the female who engaged in that kiss. That study is “Prevalence and Persistence of Male DNA Identified in Mixed Saliva Samples After Intense Kissing.”

February 16, 2017

You’re invited to the Improbable Research show at the AAAS meeting Saturday

Join us, if you’re in Boston this Saturday night, at the annual Improbable Research session at the AAAS Annual meeting! Here are details:

Join us, if you’re in Boston this Saturday night, at the annual Improbable Research session at the AAAS Annual meeting! Here are details:

AAAS Annual Meeting, Sheraton Boston Hotel (in the Prudential Center), in Constitution Ballroom A, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. — February 18, 2017, Saturday, 8:00 pm. — This year’s Improbable Research session will feature:

Marc Abrahams (founder of the Ig Nobel Prize ceremony) will profile the new Ig Nobel Prize winners

Nicole “FYFD” Sharp will present updated discoveries from her research on the fluid dynamics of the Boston Molasses Flood

Improbable Research podcast stars, doing dramatic readings from Ig Nobel Prize-winning studies and patents: researchers Jean Berko Gleason , Nicole “FYFD” Sharp, Melissa Franklin , Daniel Rosenberg , Robin Abrahams , Richard Baguley , Chris Cotsapas .

Soprano Maria Ferrante , accompanied by Dr. Thomas Michel , singing songs from Ig Nobel operas.

World premiere of an opera song about the Dunning-Kruger effect , with music by Giacomo Puccini (composer of 13 operas) and words by Marc Abrahams (librettist of 21 Ig Nobel operas), performed by Maria Ferrante and Dr. Thomas Michel.

This evening special session is open free to the public. BUT NOTE: Every year this session fills rapidly, so we suggest you arrive a little early, if you want to get into the room.

This is the research study that introduced the Dunning-Kruger effect:

Sensation Seeking, Sports Cars, and Hedge Funds (new study)

“The emerging [hedge fund] manager who goes out and buys a fancy sports car right off the bat is someone you probably want to avoid.”

– informed an article in Business Insider (Singapore), February 2016. But was the statement measurably valid? To find out Stephen Brown, Yan Lu, Sugata Ray and Melvyn Teo set up a research project to empirically investigate the so-called ‘Red Ferrari Syndrome’.

– informed an article in Business Insider (Singapore), February 2016. But was the statement measurably valid? To find out Stephen Brown, Yan Lu, Sugata Ray and Melvyn Teo set up a research project to empirically investigate the so-called ‘Red Ferrari Syndrome’.

An analysis of 48,778 hedge funds (with reference to the automobile preferences of the funds’ managers, and the funds’ results over time) showed striking results.

“The empirical results are striking. We find that hedge fund managers who purchase performance cars take on more investment risk than do fund managers who eschew performance cars. Specifically, sports car drivers deliver returns that are 1.80 percentage points per annum more volatile than do non-sports car drivers. This represents a 16.61 percent increase in volatility over that of drivers who shun sports cars. Similarly, drivers of high horsepower and high torque automobiles exhibit 1.14 and 1.25 percentage points per annum more volatility, respectively, in the funds that they manage than do drivers of low horsepower and low torque automobiles.”

See: Sensation Seeking, Sports Cars, and Hedge Funds NYU Working Paper, December 2016.

The photo shows the new, red, Ferrari J50

February 15, 2017

Nobel laureates don’t grow on trees

Nobel laureates don’t grow on trees, but they do go a-wandering in pleasant places. Sheldon Glashow (standing on the left, and possessor of a 1979 Nobel Prize for physics) and Rich Roberts (standing on the right, and possessor of a 1993 Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine) sent us this photo of them in Bali.

Rich Roberts writes:

“Taken in the monkey forest in Bali yesterday. The gentleman in the middle is from Brazil. His name is Oscar, and it was bought for him by his girlfriend. We thought you might find a good use for this photo.”

Until we find a good use for the photo, we are posting it here on the Improbable Research blog.

Marc Abrahams's Blog

- Marc Abrahams's profile

- 14 followers