Marc Abrahams's Blog, page 219

June 6, 2017

Lies, Lies, Lies — and the people who research why people do that

An article called “WHY WE LIE: THE SCIENCE BEHIND OUR DECEPTIVE WAYS,” in the June 2017 issue of National Geographic magazine, explores research about lying. Three of the researchers discussed there — Bruno Verschuere, Kang Lee, and Dan Ariely — are Ig Nobel Prize winners.

Yudhijit Bhattacharjee, the journalist who wrote the article, writes about them:

… “The truth comes naturally,” says psychologist Bruno Verschuere, “but lying takes effort and a sharp, flexible mind.” Lying is a part of the developmental process, like walking and talking. Children learn to lie between ages two and five, and lie the most when they are testing their independence….

Kang Lee, a psychologist at the University of Toronto, sees the emergence of the behavior in toddlers as a reassuring sign that their cognitive growth is on track. To study lying in children, Lee and his colleagues use a simple experiment. They ask kids to guess the identity of toys hidden from their view, based on an audio clue. For the first few toys, the clue is obvious—a bark for a dog, a meow for a cat—and the children answer easily. Then the sound played has nothing to do with the toy. “So you play Beethoven, but the toy’s a car,” Lee explains. The experimenter leaves the room on the pretext of taking a phone call—a lie for the sake of science—and asks the child not to peek at the toy. Returning, the experimenter asks the child for the answer, following up with the question: “Did you peek or not?”…

Ariely became fascinated with dishonesty about 15 years ago. Looking through a magazine on a long-distance flight, he came across a mental aptitude test. He answered the first question and flipped to the key in the back to see if he got it right. He found himself taking a quick glance at the answer to the next question. Continuing in this vein through the entire test, Ariely, not surprisingly, scored very well. “When I finished, I thought—I cheated myself,” he says. “Presumably, I wanted to know how smart I am, but I also wanted to prove I’m this smart to myself.” The experience led Ariely to develop a lifelong interest in the study of lying and other forms of dishonesty…. The question Ariely finds interesting is not why so many lie, but rather why they don’t lie a lot more…. unless one is a sociopath, most of us place limits on how much we are willing to lie. How far most of us are willing to go—Ariely and others have shown—is determined by social norms arrived at through unspoken consensus, like the tacit acceptability of taking a few pencils home from the office supply cabinet…

June 5, 2017

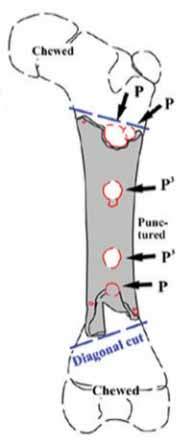

‘Neanderthal bone flutes’ not ‘Neanderthal bone flutes’ after all?

The first ‘Neanderthal cave bear bone flute’ from the Middle Palaeolithic was believed to have been discovered in the 1920s in Potočka Zijalka Jama Cave, Slovenia. But are such finds really ‘Neanderthal bone flutes’ or simply products of Ice Age spotted hyena scavenging activities on cave bear cubs in European cave bear dens?

The first ‘Neanderthal cave bear bone flute’ from the Middle Palaeolithic was believed to have been discovered in the 1920s in Potočka Zijalka Jama Cave, Slovenia. But are such finds really ‘Neanderthal bone flutes’ or simply products of Ice Age spotted hyena scavenging activities on cave bear cubs in European cave bear dens?

The latter hypothesis is presented by Dr Cajus G. Diedrich of Paleo-Logic, Independent Institute of Geosciences, in the journal Royal Society Open Science, 2 : 140022. In which he asserts, in no uncertain terms, that :

“The ‘cave bear cub femora with holes’ are, in all cases, neither instruments nor human made at all.”

The paper can be read in full here.

Also see: Melanesian nose-flutes – did they ever exist?

June 2, 2017

Troy Hurtubise is upping his game

Troy Hurtubise, whose early fame came from his quest to build a suit of armor that would protect him against grizzly bears — a years-long effort that was documented in the film Project Grizzly, and which led to Troy being awarded the 1998 Ig Nobel Prize in the field of safety engineering, and who has had many subsequent adventures, and who has written adventure-filled books — is upping his game.

I am North Bay inventor Troy Hurtubise and I am looking to raise money for a new project. Pandora’s Box is the code name for my latest invention with the goal of harvesting dark matter. All proceeds will go towards the research and development of this project.

In a world where many people think small (and some people hardly think at all), Troy always thinks big.

Troy made a short video to explain his new quest. It begins with Troy’s simple admission: “What I’ve done is something science would never think of”:

Here’s Project Grizzly:

“Paper About Plagiarism Contains Plagiarism”

“Paper About Plagiarism Contains Plagiarism” is the headline of an item in the Neuroskeptic blog. The item begins:

“Regular readers will know that I have an interest in plagiarism. Today I discovered an amusing case of plagiarism in a paper about plagiarism.

“The paper is called The confounding factors leading to plagiarism in academic writing and some suggested remedies. It recently appeared in the Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association (JPMA) and it’s written by two Saudi Arabia-based authors, Salman Yousuf Guraya and Shaista Salman Guraya.”

Here’s a glimpse at the top of the paper itself (well, at an image of that):

June 1, 2017

Does a herdsman-jilted llama shed tears? [research study]

“

Sexual relations between shepherds and the members of their flocks have existed for millennia, leading to the development of a certain type of love between them. The female llama, a ruminant related to the camel, is said by the local people in the Andean high plateau to weep with tears of jealousy when the herdsman replaces her with another female llama. The abandoned llama circles around the new couple, shedding tears of jealousy and sadness. I have had the opportunity to ask several shepherds about this. They told me that a replaced llama may gaze sadly at the new couple, but they had never seen one weep.“

An extract from : Tear Apparatus of Animals: Do They Weep? (in: The Ocular Surface, Volume 7, Issue 3, July 2009, Pages 121-127) by Juan Murube del Castillo MD PhD, professor emeritus of ophthalmology, at the University of Acalà, Madrid, Spain.

May 31, 2017

Fruit, on the brain: Big deal, theoretically

Eating lots of sugar is good for humanity, and eating lots of sugar is bad for humanity. Sugar consumption (also known as “the consumption of sugar”) may be the key to understanding all sorts of things, perhaps. Here are two arguments about that.

Eating lots of sugar is good for humanity, and eating lots of sugar is bad for humanity. Sugar consumption (also known as “the consumption of sugar”) may be the key to understanding all sorts of things, perhaps. Here are two arguments about that.

Sugar explanation 1.) You could, if you wanted to, read this article about brains and then conclude that eating larger amounts of sugar is what gave us big brains. If you wanted to, you could argue that. The article is called “What Really Made Primate Brains So Big? — A new study suggests that fruit, not social relationships, could be the main driver of larger brains.”

It says, in part:

That makes sense, because fruit is much more nutrient-dense source of food than foliage, says Katherine Milton, a physical anthropologist at the University of California at Berkeley who researches primate dietary ecology, and was not involved in this study. “Because highly folivorous [leaf-eating] primates are generally taking in less ready energy per unit time than highly frugivorous [fruit-eating] primates, one would think their brain size would correlate with this dietary difference,” Milton said…

“The cognitive complexity that is required to become more efficient at foraging for those things would also provide the selective pressure to increase brain size,” DeCasien says.

Sugar explanation 2.) You could, if you wanted to, read this article about sugar and then conclude that eating larger amounts of sugar is killing off humanity. The article is called “Sweet poison: why sugar is ruining our health“.

May 30, 2017

Mosquito Neural Netting: To identify the sound of a single mosquito

A complex new attack on mosquitoes, sort of, is outlined in this new study about identifying the sound of a single mosquito:

“Mosquito Detection with Neural Networks: The Buzz of Deep Learning,” Ivan Kiskin, Bernardo Pérez Orozco, Theo Windebank, Davide Zilli, Marianne Sinka, Kathy Willis, Stephen Roberts, arXiv:1705.05180, May 15, 2017.

The paper points out, especially, a limitation encountered in a previous attempt to enlist technology against mosquitoes:

“Chen et al. [6] attribute the stagnation of automated insect detection accuracy

to the mere use of acoustic devices, which are allegedly not capable of producing

a signal sufficiently clean to be classified correctly. As a consequence, they

replace microphones with pseudo-acoustic optical sensors, recording mosquito

wingbeat through a laser beam hitting a phototransistor array – a practice already

proposed by Moore et al. [22]. This technique however relies on the ability

to lure a mosquito through the laser beam.”

BONUS: A very different approach to battling mosquitoes is outlined in the NIH report “Novel insecticide blocks mosquitoes’ ability to urinate.”

May 29, 2017

The Cheese Scholars Collective examine Cheese Naming

If you’ve ever wondered how, where, when and/or why cheeses end up with names like Ticklemore, Fat Bottom Girl, or Constant Bliss then the Cheese Scholars Collective is here to help. “Dedicated to facilitating the constructive

If you’ve ever wondered how, where, when and/or why cheeses end up with names like Ticklemore, Fat Bottom Girl, or Constant Bliss then the Cheese Scholars Collective is here to help. “Dedicated to facilitating the constructive

exchange of scholarly perspectives

on cheese and its makers”, it was formed during a workshop held 24-26 June 2009 in Totnes, Devon, England. Since then, members of the collective have published a series of essays on ‘Naming Cheese’ in the journal Food, Culture & Society, 15:1, 7-41.

By way of example, here is a short extract from the essay ‘What Did She Call that Cheese?’ by Dr Cleary (now at the William Angliss Institute, Melbourne, Australia)

“[…] while words help people to make sense of the world by organizing their experiences, understanding is not simply a property of a text, it is also a quality of experience. In this respect meaning (and identity) is animated by ‘rough feelings and sensings’ which are then transformed into distinctive signs that help to make the world ‘readable and transmittable’ (Cooper 2006;1,549-63). Viewed in this way, naming (as that which organizes) can be seen as a series of compositional acts rather than a completed, self-sufficient structure.”

Citation: Harry G. West, Heather Paxson, Joby Williams, Cristina Grasseni, Elia Petridou & Susan Cleary (2012) Naming Cheese, Food, Culture & Society, 15:1, 7-41

The image [based on a photo by Jon Sullivan] shows a slice of well-matured ‘Stinking Bishop’, available from Charles Martell & Sons Ltd. Dymock, UK.

May 28, 2017

Join the 22nd Dead Duck Day celebration, on June 5th

Monday June 5th, 2017 is the 22nd edition of Dead Duck Day. At exactly 17:55 h we will honor the mallard duck that became known to science as the first (documented) ‘victim’ of homosexual necrophilia in that species, and earned its discoverer (Kees Moeliker) the 2003 Ig Nobel Biology Prize.

Monday June 5th, 2017 is the 22nd edition of Dead Duck Day. At exactly 17:55 h we will honor the mallard duck that became known to science as the first (documented) ‘victim’ of homosexual necrophilia in that species, and earned its discoverer (Kees Moeliker) the 2003 Ig Nobel Biology Prize.

Dead Duck Day also commemorates the billions of other birds that die(d) from colliding with glass buildings, and challenges people to find solutions to this global problem.

The event will include a review of this year’s (animal) necrophilia news: the world’s second officially homosexual necrophiliac duck will make his first posthumous public appearance. [Some people have been waiting 22 years for this moment.]

For FULL DETAILS, see the Dead Duck Day official announcement.

Here’s an exciting action photo from last year’s Dead Duck Day celebration:

Profile of the first double-Ig Nobel Prize winner, Jacques Benveniste

Jacques Benveniste [pictured here] was the first person (but not the last!) to be awarded more than one Ig Nobel Prize. John Welford the renowned “professional librarian, now semi-retired, who writes articles based on material gleaned from obscure books and journals,” crafted a profile of Benveniste. Here are some highlights:

“… Having – as he thought – produced convincing proof of the memory-retaining capacity of water, Jacques Benveniste thought he saw a way of cashing in on his work. He left Inserm (it is possible that he was pushed out rather than resigning his post voluntarily) and founded a company named the Digital Biology Laboratory, through which he hoped a make a vast fortune by completely revolutionizing the world of medicine.

“His new idea was that the memory retained by a quantity of water could be digitized and then transmitted to another body of water via a telephone line or the Internet. If one assumed that the first flask of water contained the cure to a particular ailment – which might well be assumed by a convinced homeopath – then the digitized memory of that cure could be sent anywhere in the world and transfer its miraculous powers to patients who would only need a glass of water and a computer (these days, a smartphone would probably have been sufficient). Presumably, a certain amount of money would also have flowed into the coffers of the Digital Biology Laboratory….

“Jacques Benveniste had the unique honor of winning two Ig Nobels, the first being in 1991. This was the first such award in the field of Chemistry. However, his persistence in continuing to astonish the scientific world earned him a second Ig Nobel, in 1998. He did not collect either award in person, but said that he was happy to be recognized in this way because it proved that the people making the awards did not understand the first thing about anything.

“Unfortunately, there was no possibility of Jacques Benveniste ever collecting a third Ig Nobel because he died in 2004 at the age of 69, with his revolutionary claims still unproven.”

“

Marc Abrahams's Blog

- Marc Abrahams's profile

- 14 followers