Paula Vince's Blog: The Vince Review, page 23

July 6, 2021

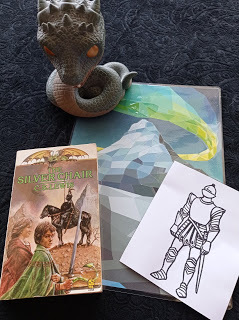

'The Silver Chair' by C.S. Lewis

Or 'The One with the Lost Prince'

Caution: A few minor plot spoilers may lurk beneath the discussion points.

I'd forgotten what a meaningful and very cool quest tale this is.

Eustace Scrubb is back in Narnia, this time with his school friend, Jill Pole. Several Narnian decades have lapsed since his first visit, and the boy King Caspian is now a very old man. Eustace and Jill have been given the task to track down his missing son, Prince Rilian, heir to the throne. They'll have to embark on a dangerous journey to the north beyond the land of the giants. Puddleglum, a pessimistic marsh-wiggle who lives in a swamp, agrees to be their guide.

What I loved even more than before

1) This seems to be the only intentional, human-induced whisking off to Narnia on record, so to speak. Eustace and Jill actually set up quite an elaborate ritual by requesting to be taken, at a most vulnerable moment when they're both fed up with bullies and their depressing co-ed school. I guess we can regard the result as an act of grace, for Eustace knows full well that nobody can order Aslan about. They can only ask. It turns out to be a wooing from the other side, too. Before long, Aslan tells Jill,'You would not have called me unless I had been calling you.'

2) Many of Lewis' girls are feisty, and Jill has a particularly abrasive streak that makes me smile. Her prickly pride and disposition to show off is the reason why Eustace falls off the cliff at the outset, and if it had been a normal plummet as she thought, she would have killed him! All through the story, she keeps a secret eye on Eustace's reactions, forever comparing them to her own. If she feels she comes out better, she gets a tickle of pride. But if he appears to come out top, she's quite woebegone. There's always an attitude of something to prove, if only to herself. She's quite a character.

3) I totally understand the distracting effect on both children as soon as they hear about Harfang, the supposed oasis of the gentle giants, where they will enjoy fantastic hospitality. They can think of nothing but the short term comforts of soft beds, tasty food and warm fires. I don't blame them in the least after their cold trek, but Lewis' point is clear. Temporal comfort wins the day with Jill and Eustace. They stop looking at the bigger picture, completely sidetracked by the quick fixes they're anticipating. They forget to rehearse the signs Aslan has given them to keep their minds on the quest to find Prince Rilian. It's his little nudge for any of us inclined to forget the broader picture of our lives and goals. (And in the case of our little trio, they were lucky to escape with their lives.)

4) The description of the underworld is wonderful! Their descent puts us readers right in the picture so we can almost see the weird forms of growth, smell the dank, close earth and experience the hush of the solemn underground city. And their ascent later on is most tense and eventful.

5) The chapter with the titular Silver Chair is among my favourites of any story ever. What a conflict of interests! What a test of faith! What a convincing appearance of extenuating circumstances! How easily they could have reasoned their way out of obeying Aslan's final directive to them. What curly plot twists, and final proof that enchantment was indeed happening, but just not the way they expected. Aslan did warn them that it's important to know the signs by heart and pay no attention to appearances. But how close they came to being sucked in.

6) Directly after this is the brilliant incident in which the green witch does her best to convince them that the world they know so well is a mere dream. She uses the old trick of trying to make them believe there is no reality beyond what their physical senses can make out from their limited environment. This mirrors another theological lesson of Lewis'. Because we can't detect a greater realm than planet earth with our tangible senses, some people are convinced that such speculations are akin to fairy tales. And Jill, Eustace, Puddleglum and Rilian almost succumb to the same reasoning.

7) I like how Rilian and even Eustace are so keen to venture down to the land of Bism at the world's bottom, with the tempting gnome Golg as their guide. It's clearer to them later that it's just pride and hankering for personal glory that caused them to delay their all-important trip back toward the world's surface. Just because something sounds awesome, doesn't mean we should drop everything and do it.

8) Puddleglum!! What a hero and legend. I wish I had a marsh-wiggle for a friend. I read that Lewis based him on his long-term gardener and friend, F.W. Paxford, who he described as, 'an inwardly optimistic, outwardly pessimistic, dear, frustrating, shrewd countryman of immense integrity.'

9) This is just a speculation of mine, but I'm sure if Lewis were alive, he would think the whole world has turned crazy like Experiment House, that up-to-date school he considered so dodgy. He drops several hints in the form of little digs. For example, Eustace and Jill are bemused when referred to as a Son of Adam and Daughter of Eve, because their school curriculum includes no teaching about Adam and Eve. And later, both kids bow to the giants of Harfang, because Jill hasn't been taught to curtsey in her environment of equal opportunity. Whatever we might think of our current PC era, I'm pretty sure Lewis wouldn't have been a fan.

10) Caspian's death scene is one of the finest and most uplifting I've come across.

What I wasn't a fan of this time round.

1) Okay, although I love Eustace and Jill, I feel this begs to be said. All through the story, the real hero of the quest turns out to be Puddleglum. It is always he who makes the wisest decisions, and refuses to succumb to the human weaknesses of his two young companions. So as far as the quest is concerned, why not simply assign the saving of Prince Rilian to the marsh-wiggle in the first place? Jill and Eustace might as well have stayed home. They were a liability to Puddleglum in the same way he was a benefit to them. I would have loved to see these two come up with some heroic stuff off their own bats and save the day just once. As it was, they were just along for the ride for the most part.

2) I was a bit disappointed that at no point did Aslan address Jill's automatic habit of comparing herself to Eustace every step of the way. I'd expected the great lion to help her confront this default reaction of hers and learn to stop the pointless game of comparison. It would have been fun to read.

Some great quotes

Puddleglum: We've done the silliest thing in the world by coming here at all, but now that we're here, we'd best put a bold face on it. (At the giants' doorstep.)

Giant King: After them, or we'll have no man pie tomorrow.

Witch: Your sun is a dream, and there is nothing in that dream that was not copied from the lamp. The lamp is the real thing, the sun is but a tale; a children's tale.

Witch: You have seen lamps, so you imagined a bigger, better lamp and called it the sun. You've seen cats, and now you want a bigger, better cat and it is to be a lion. Well, it's a pretty make-believe, though to say truth, it would suit you all better if you were younger. Look how you can put nothing into your make-believe without copying it from the real world, this world of mine, which is the only world.

Puddleglum: Supposed we have only dreamed or made up all those things - trees and grass and sun and moon and Aslan himself. Then in that case, the made up things seem a good deal more important than the real ones. Suppose this black pit of a kingdom of yours is the only world. Well, it strikes me as a pretty poor one. And that's a funny thing when you come to think of it. We're just babies making up a game, if you're right. But four babies playing a game can make a play world which licks your read world hollow. That's why I'm going to stand by the play world. I'm on Aslan's side, even if there is no Aslan to lead it. I'm going to live as like a Narnian as I can, even if there is no Narnia

Narnia's oldest dwarf: And the lesson of all is, your Highness, that those Northern Witches always mean the same thing, but in every age they have a different plan for getting it.

Stick around, because we'll soon conclude with The Last Battle

June 29, 2021

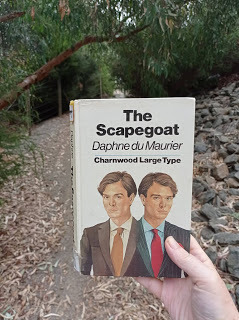

'The Scapegoat' by Daphne Du Maurier

By chance, John and Jean--one English, the other French--meet in a provincial railway station. Their resemblance to each other is uncanny, and they spend the next few hours talking and drinking - until at last John falls into a drunken stupor. It's to be his last carefree moment, for when he wakes, Jean has stolen his identity and disappeared. So the Englishman steps into the Frenchman's shoes, and faces a variety of perplexing roles - as owner of a chateau, director of a failing business, head of a fractious family, and master of nothing.

Gripping and complex, The Scapegoat is a masterful exploration of doubling and identity, and of the dark side of the self.

MY THOUGHTS:

This doppelganger/mistaken identity yarn is written with a flourish of du Maurier suspense, and also a tinge of the Gothic, although it was set in the 1950s. Two look-alikes come face to face in a city pub. John, an English historian, is a lonely orphan who regrets being a perpetual spectator of other people's lives. Jean de Gue, the Frenchman, feels shackled by family demands that stem back for centuries, including business, close relationships and community expectations. So Jean decides to do a quick swap when John is asleep, running off with his clothes and identity, leaving John to face the mess he's left behind in his own chateau, should he choose to do so.

John finds himself between a rock and a hard place. He feels too sympathetic not to play along with the act, since so many people depend on Jean. Yet he also feels extremely guilty for hoodwinking the trusting souls. He has to improvise when it comes to being a husband, son, brother and father, since he's been none of these things for many years, if ever. Fortunately for him, a guy like Jean who would cut and run like that is an erratic role model whose shoes are not hard to fill.

It seems that while Jean was a happy-go-lucky chap who was popular with many people, his own siblings consider him a jerk. His sister Blanche has not spoken to him for over 15 years, and John can't figure out why. This story held my interest all the way through, although I found it hard to warm to any of the de Gue family except for Jean's 10-year-old daughter Marie-Noel, and one other character who sadly dies.

But one question du Maurier leaves us with is whether or not familiarity may breed contempt. As long-term secrets come to light, John finds genuine affection for Jean's family welling up. But would it dry up if he had as long a history with them as Jean? I guess I liked the pair of doppelgangers, but only just. John makes some questionable decisions, and for all his energy and charisma, Jean is such a cocky ratbag!

Yet having said that, I kept hoping John would keep stacking up the brownie points for Jean in his family's eyes.

🌟🌟🌟½

June 22, 2021

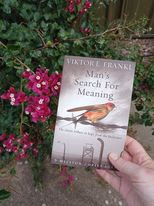

'Man's Search for Meaning' by Viktor E. Frankl

Psychiatrist Viktor Frankl's memoir has riveted generations of readers with its descriptions of life in Nazi death camps and its lessons for spiritual survival. Based on his own experience and the stories of his patients, Frankl argues that we cannot avoid suffering but we can choose how to cope with it, find meaning in it, and move forward with renewed purpose. At the heart of his theory, known as logotherapy, is a conviction that the primary human drive is not pleasure but the pursuit of what we find meaningful. Man's Search for Meaning has become one of the most influential books in America; it continues to inspire us all to find significance in the very act of living.

MY THOUGHTS:

This is my choice for the Classic in Translation category of this year's Back to the Classics Challenge. My edition was translated beautifully by Ilse Lasch. It was written in (9 days?) by the Viennese psychotherapist Viktor Frankl shortly after his release from a concentration camp. He'd been a long-term prisoner at Auschwitz and Dachau during World War Two. In a series of revelations and anecdotes, Frankl describes daily life along with the survivor's mindset most likely to last the distance. What makes it such an enduring classic is his conviction that the attitude he formed to pull him through may also be applied to any not-so-extreme lifestyle.

Prisoners were stripped of all their belongings and possessed nothing but their bare bodies and the breath that passed through them. Comrades were regularly trundled off to the gas chamber, and everyone lived with the knowledge that they might be next. Frankl explains that appearing fit for work was anyone's only hope, so men shaved daily, in an attempt to look as young and pink cheeked as possible while suffering and starving.

He describes the mental torture that went hand in hand with this physical privation. Frankl considers it an inevitable, invasive form of inferiority complex. They'd all fancied themselves to be 'somebody' in their old lives, as we all do. I guess we're all born with the illusion that we're the centre of the world, since we're all the centre of our own world. When you abruptly become a complete nonentity, addressed by your number rather than your name, any delusions of grandeur are shattered. (Frankl's number was 119 104.)

So that was his setting of the scene. It was fascinating to read Frankl's personal testimony about making meaning out of such a degraded life, when it's so easy to empathise with the majority of Frankl's fellow prisoners, who considered their best days were gone forever.

He suggests the power of imagination coupled with the power of love is unbeatable. Frankl describes how he retreated into mental images of interaction with his wife which the prison staff knew nothing about. He had no idea if she was dead or alive, (and it turns out she was dead) but either way, nothing could touch the strength of his great love, thoughts and image of her. So as any daydreamer can testify, 'the intensification of inner life helps prisoners find a refuge from emptiness.' Yeah!!

In Part 2 of the book, Frankl describes his own theory of Logotherapy, which is written in more of a clinical style geared toward members of his own profession. After trying to wrap my head around it, I managed to distill his three main ways of deriving meaning, with help from the far more engaging Part 1.

1) Creative/Active Way. This describes our opportunities to realise values using our own effort and creative work. So write a book, make a film, start a business or non-profit organisation, join a cause or keep a regular blog.

2) Experiential Way. Frankl says, 'a passive life of enjoyment affords man the opportunity to obtain fulfillment in experiencing beauty, art or nature. (I admit this one appeals to me.) So encounter good people, visit awesome places, or if both are limited, read great books.

3) Attitudinal Way. I guess this is the crux of the whole book. It's the path to meaning for those who face unavoidable suffering or circumstances we'd never choose. Although we can't change the condition, we can change our attitude toward it. When we make a firm decision to behave in a specific, stable manner, no matter what life throws at us, we fill our lives with meaning and personal triumph. Best of all, nobody else ever needs to know.

And that leads to Frankl's great quote.

'Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms - to choose one's attitude in any given set of circumstances. To choose one's own way.'

Since I scribbled so many of his brilliant quotes in my scrapbook, I'll finish with a few others. Why bother trying to paraphrase perfection?

'Most men in a concentration camp believed that the real opportunities of life had passed. Yet in reality, there was an opportunity and a challenge. One could make a victory of those experiences, turning life into an inner triumph, or one could ignore the challenge and simply vegetate, as did the majority of the prisoners.'

'We had to learn ourselves and furthermore we had to teach the despairing men that it did not matter what we expected from life, but rather what life expected from us.'

'We needed to stop asking about the meaning of life and instead to think of ourselves as those who were being questioned by life, daily and hourly. Our answer must consist not in talk and meditation but in right action and in right conduct.'

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

June 15, 2021

Villainous Brothers and Sisters

I thought this could be a revealing alternative list to that which we see more often, which is, of course, heroic brother and sister duos. The lovable pairs are awesome, but they're very familiar to us by now. We can surely all rattle off examples such as Jem and Scout Finch, Francie and Neeley Nolan, Ron and Ginny Weasley, Matthew and Marilla Cuthbert. But they're such well-known legends, I don't even feel tempted to write that list. I prefer my book lists to be more quirky or gathered from further afield. That's why I challenged myself to come up with baddies rather than goodies, when it comes to literary brothers and sisters.

They're out there folks, suggesting that unfortunate gene pools do exist, or that questionable upbringing may strike double. It would seem some parents get an opportunity to spread their unfortunate chromosomes through both male and female channels, and when this double trouble makes it into the pages of our favourite novels, all the other characters who have to deal with them must look out.

Without further ado, here they are.

Anatole and Helene Curagin

These two have devastating good looks, and use their physical beauty to mess up the lives of War and Peace's favourite couple, Pierre and Natasha. The ravishingly fashionable society chick Helene gets her greedy clutches stuck into naive Pierre Bezukhov the moment she discovers he's inherited a fortune. He's off to the altar with this evil goddess before he knows what's hit him. Then down the track, her impossibly gorgeous younger brother Anatole seduces Natasha Rostov, an innocent teenager who fully intends to stay loyal to her fiance, Andrei Bolkonsky. But Anatole's pressure to elope is just too irresistible for her to withstand. (See my review.)

Hindley and Catherine Earnshaw

They share the wild family genes of violent and unrestrained passion. Hindley is a despicable bully to his father's adopted foundling, Heathcliff, which comes back to bite him later when he becomes a dissolute drunkard. And Catherine is a screeching diva to her husband Edgar Linton, who she marries just to get society's nods of approval. To a large extent, both brother and sister simply blow themselves out, like raging hurricanes. (Here's my review of Wuthering Heights.)

John and Isabella Thorpe

Look out, city of Bath, for the arrival of this pair of hypocritical fakes. John makes up stories on the spur of the moment to his own advantage, and never realises he's a crashing bore. Isabella is a bit more polished in her social climbing attempts, but anyone who gets to know her well enough can see she's just as insincere as her brother. Unluckily for their victims, they've both inherited what must be the family trait of manipulation. (See my review of Northanger Abbey.)

Alecto and Amycus Carrow

This duo is bad news for Hogwarts in the lead up to the final battle between the forces of good and evil. They are a pair of Death Eaters who are both experts at the dark arts, and are appointed joint deputy heads of the school by the corrupt powers who have taken over the Ministry of Magic. During their reign of terror, cruel punishments are part of everyday life. The Silver Trio, Ginny, Neville and Luna, are hard pressed to figure out how to keep Dumbledore's Army functioning beneath the Carrows' cruel and beady eyes. (No official review but Potter posts are common on this blog.)

Edward and Jane Murdstone

As despicable a pair of siblings as you'd find anywhere, these nasty pieces of work believe their savage piety is fully justified. Edward is in the habit of marrying innocent young women and totally breaking their spirits. In the case of poor Clara Copperfield, his sanctimonious and mean-spirited sister Jane comes to live with them, to help him turn the screws. And they both treat her young son, David, like dirt. (Start here for my thoughts on David Copperfield.)

Anna Karenina and Stepan Oblonsky

These two are united in holding their marital vows super loosely, even though they both claim to be committed to their spouses and children. Stepan cheats on his wife, Dolly, whenever he has an opportunity, and regards her discovery as a minor hindrance he'll have to get his sister to help him smooth over. Anna herself meets Count Alexei Vronsky on the way to do her brother's dirty work, and instantly decides he is far more desirable than her own husband, who she's been content with until now. (Review is here.)

Now, drum roll for my favourite bro and sis duo, who I can't help liking despite their villainous status.

Henry and Mary Crawford

These two are both easy to like, with spades of charisma, but their family weakness seems to be a sort of shallowness. Henry enjoys flirting with firmly attached or hard-to-get women just to see if he can, and Mary is a social climber who tends to be blaise and flippant about good, sound values. But both brother and sister get burned in their own games. Henry really does come to love Fanny Price, and Mary feels the same for Edmund Bertram. Some readers prefer these bad kids on the block to the main characters of Mansfield Park, and I can count myself among them. (And start here for my thoughts on Mansfield Park.)

Now, how do you like my picks? Have you a favourite villainous brother and sister duo of your own?

June 8, 2021

'The Voyage of the Dawn Treader' by C. S. Lewis

Or 'The One with the Lost Noblemen'

Warning: There are some minor plot spoilers in my discussion points, for those who have no idea what this is about.

I greatly anticipated this book, because who can resist a good sea yarn, or new frontiers tale, or fantasy adventure? The Voyage of the Dawn Treader combines all three, with plenty of awesome spiritual applications and Christian parallels to boot.

This time Edmund and Lucy are swept back into Narnia when the painting of an intriguing looking ship suddenly bursts through the barriers of its frame, sweeping them into the sea. Their annoying and entitled cousin Eustace is swept in with them, to his fear and horror.

The ship belongs to the boy king Caspian, only three years older than when they last saw him. He and his crew are on a quest to track down his dead father's seven loyal friends, who were banished during the reign of Miraz, and Reepicheep the brave mouse captain aims to push on beyond the edge of the known world. The three newcomers are unintentionally along for the ride, and while this suits Lucy and Edmund just fine, Eustace has other ideas; especially at first.

Wow, I loved this multi-layered story, and feel my thoughts will only scratch the surface, just like Eustace's attempts to shed his dragon skin. Still, here goes.

What I appreciated more than before

1) Lewis' strong belief in the value of a great story comes through loud and clear. The narrator keeps making digs at Eustace for not having read 'the right sort of books.' He was brought up to shun imaginative fiction as pointless and time-wasting, and stick to dry old practical text books. But as I hope any fellow fiction reader agrees, well-executed stories actually fill our spirits with deeper truths about the nature of life which is difficult to acquire any other way. In this story itself, Lewis makes sure Eustace's deficiency in this area proves to be a stumbling back many times. When it comes to intuitively working out the proper action in response to moral and emotional challenges life might deliver, thick books about agriculture and commerce just aren't going to cut it!

(Similarly, Edmund gets praised at one point, for being the only member of the little party who has read plenty of detective fiction. It puts him in the position to instantly realise there's something fishy about finding a set of Narnian clothes and armour with no body.)

2) The incident in which Aslan helps Eustace cast off his dragon form is awesome. It might even be one of the best analogies about the limitations of the self help movement ever written. Eustace simply cannot tear off all his own layers of dragon skin, no matter how hard he tries. It's impossible for his own teeth to dig in that deep. Aslan stands back to let him figure that out for himself before coming in for the final, potent tear. The only effort which makes a vital difference is the one which Aslan applies, when Eustace comes to the end of himself. And this is a perfect example of my first point coming to play. Any attentive reader might twig that our own futile attempts to tear off our dragon skins, whatever forms they may take, are only scratching the surface.

3) Poor heartbroken Caspian's plight shows that with great honour comes great responsibility. He wants to press through with Reepicheep beyond the edge of the known world to Aslan's domain, but the loyalty he owes to his many subjects is pointed out by the others. And it almost breaks him. A good lesson maybe for any readers who chafe against anonymity. It does have its benefits.

4) Lucy's temptation to repeat a spell from the magician's book, to impart overwhelming physical beauty is easy to understand. Her underlying resentment about Susan being regarded as the pretty one of their family is nearly her undoing. I get the feeling Lucy's misery is kept low key, since we don't talk about such things, but it clearly simmers away, as that sort of bitterness tends to do. She's sick and tired of feeling herself to be small and overlooked. Luckily Lucy resists, but even so she weakens enough to repeat another spell to discover what her friends truly think about her. It doesn't end well, and Aslan makes sure Lucy realises that what others think of us is their own business, and none of ours. It's a murky domain to try to infiltrate, so best left alone.

5) I love the dramatic entrance of Ramandu, the elderly retired star, and his lovely daughter. Especially when Eustace comments, 'In our world, a star is a huge ball of flaming gas,' and Ramandu replies, 'Even in your world, my son, that is not what a star is, but only what it is made of.' Yes! I feel Lewis is having a shot here at reductionism, in which practical minds seek to take the magic out of everything by reducing it to its basic scientific components. Although spiritual significance is invisible to measurable technology, it's no less powerful, and should never be negated or explained away. Eustace can always be relied upon to voice the practical aspect of anything, but he learns that there's another aspect as he goes, and has come a long way by the end.

6) The quest alone is a good one. It's interesting how each of the seven missing lords ends up being accounted for.

7) The heavenly descriptions of the environment the Dawn Treader passes through as they get further east than anyone has ever before is mind-blowing. It includes intensely bright light which is cleansing rather than piercing, wonderful, light-infused fresh water, birds that appear angelic and a fragrant type of white lily that floats on the sea.

What I wasn't a fan of this time round.

1) There was basically nothing. This is an amazing book. But for the sake of saying something, perhaps the reason why Eustace becomes a dragon in the first place is sort of vague. We're told, 'Sleeping on a dragon's hoard, with greedy, dragonish thoughts in his head, he had become a dragon himself.' That seems a bit of an inadequate explanation, and very convenient for the plot, even in Narnia and the surrounding seas. But I'm willing to go with it, and even assume that the other, elderly dragon was indeed Lord Octesian, who presumably got transformed in a similar manner.

Having said this, I've got to add that I love the description of how it dawns on poor Eustace that he actually was a dragon.

2) Maybe it would have come across an even more powerful incident if we'd read about the shedding of the dragon skin first hand, rather than just getting Eustace's second hand report of what happened when he describes it to Edmund. Hmm, not sure.

Some Great Quotes.

There was a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb, and he almost deserved it. (What a brilliant, classic opening line.)

It is very unpleasant to have to go cautiously when there is a voice inside you saying all the time, 'Hurry, hurry!'

Eustace had read only the wrong books. They had a lot to say about exports and imports, governments and drains, but they were weak on dragons.

Edmund: Between ourselves, you haven't been as bad as I was on my first trip to Narnia. You were only an ass, but I was a traitor. (And kudoes to Eustace for not pressing Edmund to find out more.)

Lucy (to Edmund and Caspian): Oh, stop it, you two. That's the worst of doing anything with boys. You're all such swaggering, bullying idiots! (Whoa, that's the way you deal with the bad behaviour of two kings.)

Lucy: 'Please Aslan, what do you call soon?' Aslan: 'I call all time soon.'

Eustace: 'Do you know him (Aslan)?' Edmund: 'Well... he knows me.'

Reepicheep: Use, Captain? If by use you mean filling our bellies or our purses, I confess it will be no use at all. So far as I know, we did not set sail to look for things useful but to seek honour and adventure.

Stick around, because next will be The Silver Chair.

May 31, 2021

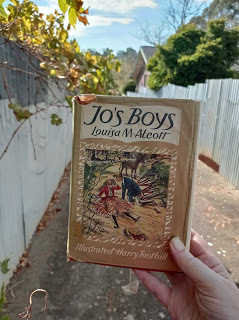

'Jo's Boys' by Louisa May Alcott

Here is the final book in the March family series. The boy students in Little Men are now ten years older and forging their paths in the world, while Jo and Fritz Bhaer anxiously watch to gauge whether or not they've lived up to their full potential. Some of the young men venture far from home, and we follow their stories. I think Emil's is the most exciting, Dan's is the most emotional and Nat's is the most relatable. Meanwhile, there is now a big University on the grounds of Plumfield, for those who choose to stay behind.

Okay, this write-up is going to be a bit gossipy, because by now we're familiar with all the Marches, Bhaers and Brookes, and there are so many divergent threads, I find it's the easiest way to write it. Here goes.

What struck me this time round, both good and bad.

1) There's a fair bit of romance in this book, but in the spirit of the original Jo and Laurie thread, Alcott still shipwrecks a few budding relationships that appeared promising. (For the record, I was never upset about Jo and Laurie's failure to launch, but I can't deny Alcott led astray thousands of readers who shipped them.) But hooray, she does give us Daisy and Nat, for which I'm grateful, because they're adorable together and perfectly suited. And she introduces new love interests for Franz, Emil, Demi and Tommy.

2) The biggest hypocrite award goes to Meg. (Don't worry, I'm half joking here.) As we know, she once had yearnings to pursue an acting career, and eventually married a poor man for love. Yet when it comes to her own daughters, she opposes the idea of Daisy marrying a charity case like Nat, and also resists young Josie's fascination with the stage. Hoping that Meg will change her mind is one of the main themes for the Brooke girls, who lived in an era when dutiful daughters obeyed their mothers implicitly.

3) Dan continues to make me feel as if he's been transplanted from a different story altogether, with his restless energy and violent outbursts. The power of genetics comes through, as Alcott gives the impression that the shadow of his restless, dissolute father still hovers over his life, although Dan never even knew the guy. It's clever how she writes it this way, and Dan remains one of her most interesting characters. The little touch of thwarted love at the end breaks my heart for him, although I'm convinced that what he wanted would never have worked in a million years!

4) The chapter entitled, 'Jo's Last Scrape' is clearly autobiographical. Louisa shows us Jo experiencing the nineteenth century version of annoying paparazzi and crazy fans. She aims to reveal the impossible juggling act it is to please the public and also look after her own well-being, because all the seemingly harmless demands on her time amount to an ocean rather than a trickle. On the last page of the story, the narrator suddenly gets a bit snarky and says she wishes she could destroy Plumfield in an earthquake with everyone in it. Ouch, I suspect Louisa was barely keeping a lid on her real life frustration at this point.

5) One character who impresses me most is young Rob, who's grown up to be a modest and dependable young man, helping both parents with tedious paperwork chores behind the scenes with no expectation of fanfare or back pats. For me, he compares favourably to some of the more showy, noisy or indulged characters. (Ahem, his younger brother and two youngest girl cousins.) Laurie and Amy's daughter Bess is nicknamed 'Princess' without the negative connotations the word contains today, yet some modern readers probably can't help filling them in. I was sure tempted to.

6) I can't help agreeing with Dan when he says that Bess, the princess, should explore the scope of her own country before dashing off overseas to sketch the beauties of Rome. Whether or not you agree with his view that all of the stone gods and goddesses are a bit namby-pamby, he makes a fair point.

7) Laurie and Amy were richer than a wedding cake! Nat and Dan felt grateful and obligated to them for their financial backing, and rightfully so, yet I can't help remembering that Laurie's prosperity was a benefit from his family line. In a way, it was the luck of the cosmic draw that he was born into big money rather than them. He and Amy lived in a mansion and also owned a flash holiday home near Miss Cameron, their era's version of a movie star, with whom they were on friendly visiting terms. And Laurie's purse seemed to be bottomless! Supporting far less fortunate young men in their chosen professions was barely scraping it. No wonder he was such a good natured, jolly uncle character. He could afford to be.

8) The two dreamy/thinking boys come out well. Demi's thread is interesting. Unlike his twin sister, he resists falling in with plans his mother and other older relatives concocted for his life long ago. All through Little Men, it looked as if everyone expected him to be a minister, but he chooses to be a journalist instead, and later gets into the publishing industry. And Nat fulfills his promise to become a polished musician, even though Jo often seems to denigrate him in her secret heart and consider him a bit of a weakling. I was tired of that, and really wanted him to show her.

9) Jack and Ned, who hardly get a mention in the this story, are regarded as Plumfield's two 'failures.' Yet we're told that Jack fulfilled his youthful ambition of becoming a businessman and raking in the dough, so I guess that in his own books, he was a smashing success. It's all relative, hey?

10) Alcott's writing is dense with other references. Reading her novels could be an education in itself, if we bother to follow all her leads. She frequently refers to the classics, or to other authors from her own time period who most modern readers are not so familiar with. It appears that Louisa expected her peers, like Charlotte Yonge, to remain timeless, yet her own name has endured for longer.

I followed a few of the more interesting sounding ones and found it well worth my time. For example, she referred to Emil as their own 'Casabianca' and I traced the reference to Felicity Hemans, the old-timer who wrote the original 'Boy Stood on the Burning Deck' poem, which has been paradied and butchered for decades. That was a 'Wow' moment for me, and to find out what Emil has in common with the boy who stood on the burning deck, you'll have to read Jo's Boys.

I guess this review or gossip-fest or whatever you'd choose to call it has gone on for long enough, but Jo's Boys is such a tying-up-of-ends sort of book encompassing so many characters, I couldn't help myself.

My final word is that I enjoyed the whole series and recommend it thoroughly.

May 23, 2021

'Little Men' by Louisa May Alcott

This is my first re-read since my youth. I remembered this book to be full of joy, because it's all about the success of Jo March's fondest ambition. She and her husband, Professor Fritz Bhaer, run a merry school for boys named Plumfield, and this story gives us a glimpse into a specific six month slab of time beneath the roof.

Louisa May Alcott was previously coerced by her publisher to write a book for girls, and resisted writing the classic which became Little Women. In her heart, she would have preferred to write a book for boys, because she felt more of an affinity with young men. So a few years after the smashing success of Little Women, she set out to please herself rather than anyone else, and I get the feeling this is the self-indulgent (but very cool) result. It's like a cry of triumph and full of the sort of high jinks and horseplay she loved.

It begins when 12-year-old Nat Blake is welcomed at Plumfield. He's the gentle son of an itinerant street musician who has recently died. Nat is deserted by his father's uncaring music partner who refuses the responsibility of an undernourished, ailing boy. But Nat acquires a golden ticket which always gains boys a place at Plumfield; a recommendation letter and sponsorship from Mr Moneybags, aka Theodore 'Laurie' Laurence.

Plumfield is a close-knit little school comprised of a bunch of blood relatives (Franz, Emil, Demi, Rob, Teddy) and boys from paying families (Jack, Ned, Tommy, George/Stuffy, Dick, Adolphus and Billy). Later additions include the two untethered orphans (Nat and Dan). There are even a few girls, as Demi's twin Daisy (Meg's kids) hates to be separated from her brother, and they invite a saucy little livewire named Nan to keep her company. Laurie and Amy's fairy-princess daughter Bess often puts in an appearance too.

What I appreciated more than before.

1) At first I feared this might prove to be too tame for 21st century readers, but a couple of boys save the story from complete cheesiness, including Dan Keane, the restless and wild street kid who pushes boundaries. Imagine placing a cynical rebel like Holden Caulfield slap bang in the middle of a moralistic Enid Blyton story, and that's similar to what we get here. Dan eggs some of the other boys to experiment with sneaky smoking and gambling at night, with dire consequences. The intrigue sure jumps up a notch with the introduction of Dan, whose pent up energy lends the book a lot of movement.

2) The resident jerk, Jack Ford, adds a strong incentive for reader indignation. Put it this way, he uses circumstantial evidence to his advantage, deeply hurting others in the process.

3) Daisy Brooke! She's an excellent example for girls who choose to revel in the domestic arts, instead of treating them like drudge work. Even better, I love how she stands by her man. Daisy was the shining light in the otherwise heartbreaking chapter entitled, 'Damon and Pythias.'

4) Tommy Bangs. I've known several such good-natured, accident prone and fun-loving boys as this young man, and enjoy his type.

5) Nat and Demi. Perhaps these two deep and thoughtful boys are my favourites. I appreciate droll Demi with his studious habits, and earnest Nat with his wistful desire to please. They make me want to move straight on to the final book.

6) Franz and Emil. We never get a great deal of background about this pair of brothers, except that they were the orphan kids of Professor Bhaer's sister, and his reason for coming to live in America in the first place. Their personalities shine through more in Little Men though, and I like what I see.

What I wasn't a big fan of this time round. (A few of these gripes are more about changing times rather than the quality of Alcott's writing.)

1) Some of the boys, especially the non-family ones, come across very stereotyped, as one aspect of their character is way overemphasized, making them wooden and predictable. For example, there's Jack the cheapskate and Stuffy the glutton. My word, I swear that boy was written solely to be the butt of fat shaming. He's only ever mentioned in relation to over-indulging in food and suffering the consequences. I kid you not! It frustrates me, as there is always far more depth to any individual than his eating habits, yet Alcott never reveals any.

2) (I skirt around a few plot spoilers here, so if you want the episodes at Plumfield to unfold as a total surprise, then proceed carefully.)The chapter entitled 'Damon and Pythias' broke my heart for poor Nat. I was disappointed in Fritz and Jo for sharing the boys' judgmental attitude that a guy should remain guilty until he's proven innocent, instead of vice versa. Sure, the poor lad had been caught telling some white lies in the past, but assuming that he'd resort to theft when he declared he didn't is a serious jump to make. Nat is obviously a highly sensitive soul, and this incident may have scarred him for life.

3) Archaic, intolerant attitudes. In the Thanksgiving chapter, the adults encourage Demi to tell the tale of the Pilgrims to his younger cousin Rob. He reports, 'The Pilgrims killed all the Indians and hung the witches and were very good.' Demi is praised for being a wonderful young historian, but oh my, I won't even begin to delve into how problematic that one sentence is! You can see for yourself.

4) Unquestioned gender inequality. Now I have to say Louisa May Alcott is actually great for her era, as she has Nan decide to pursue a medical career at a time when that was very rare. Yet she doesn't follow through for the other side. The girls were roped into helping prepare the important Thanksgiving dinner while the boys were kept on the outside of forbidden ground, sniffing and peeping. It seems there's no chance a boy would be encouraged in aspirations to be a chef. Or they would soon be snuffed out of him as 'women's work.' Alcott makes it clear that Jo prefers 'manly boys' anyway, which doesn't really sit right with me either.

On the whole...

Alcott must have done something right because she's left me eager to re-read Jo's Boys as soon as possible, out of curiosity to find out what becomes of these boys ten years down the track, when they've grown up. I'll follow up with that one soon.

And I like this quote from Jo, 'I'm a faded old woman but a very happy one.' (Since she's still got very small boys, I'd judge her to be in her thirties or nudging early forties at the most. Perhaps for her era, that was considered old.)

May 16, 2021

'Jane of Lantern Hill' by Lucy Maud Montgomery

For as long as she could remember, Jane Stuart and her mother lived with her grandmother in a dreary mansion in Toronto. Jane always believed her father was dead until she accidentally learned he was alive and well and living on Prince Edward Island. When Jane spends the summer at his cottage on Lantern Hill, doing all the wonderful things Grandmother deems unladylike, she dares to dream that there could be such a house back in Toronto... a house where she, Mother, and Father could live together without Grandmother directing their lives — a house that could be called home.

MY THOUGHTS:

This story is very dear to my heart, so I've chosen it as the Children's Classic in this year's Back to the Classics Challenge. It's technically kid's lit, but is one of those layered books you can spot extra themes in when re-reading as an adult. It offers deep refreshment to readers of any age in an easy-reading, palatable style, like spiritual medicine between covers.

It was one of Montgomery last books, published in 1937 while she was living in Toronto. I read that she was spurred by homesickness and nostalgia for Prince Edward Island. Well, this story made me homesick too, and I've never even been there!

11-year-old Jane lives in a grim old Toronto mansion with her mother, aunt and grandmother. Old Mrs Kennedy is a control freak and skillful guilt-tripper, who loves her daughter Robin (Jane's mother) with scary intensity. (LMM has given us this type of character before. Think of Teddy Kent's mum from the Emily series.) And Robin is a doormat who finds it impossible to stand up for herself, especially since her mother has everlasting ammunition to throw back in her face. Robin is separated from her husband; a man who the elderly matriarch never wanted her to marry. Robin lets her mother dress her up like a doll well into her thirties, and attends all sorts of social events to show herself off on her mother's behalf. It appears to be a lovely lifestyle but she never knows a moment of true happiness.

Young Jane lives a stifled lifestyle too. She's a practical soul who longs to be helpful but isn't allowed to do anything. Scoldings and pay-outs from her grandmother have made her super-edgy, frustrated and awkward, which generates more tongue lashings. It's a vicious circle, but still, it's the only existence Jane knows, and she adores her mother, who is afraid to show her any affection in front of the jealous old lady.

One day a letter arrives from Jane's father, Andrew Stuart, requesting that she visit him on Prince Edward Island over the summer holidays. At first Jane is petrified, since all she's ever heard about Andrew has an evil monster tinge. But the family decide it's best to agree as a one-off capitulation, to appease the beast in his lair so he'll leave them alone in future. Poor Jane is devastated and dreads every minute.

But when she arrives on the Island and meets her dad, Jane's life changes completely. Remember the old Wizard of Oz film, which switches suddenly from black-and-white Kansas to vivid, full-coloured Oz? It's easy to imagine the same thing happening here. While Jane has wonderful fun, keeping house and cooking, making new friends, and chilling with her delightful and non-conformist dad, her personality has a chance to blossom in unexpected ways without the old restraints.

Forget any feedback you might hear calling this anti-feminist hype which aims to keep girls at home scrubbing floors and washing dishes. On the contrary, it's about liberating girls to be mistresses of their own domains, curating their own environments until they reflect their inner beauty. It's about making the physical aspects of your life a triumphant statement of creativity. Jane knows that a person's home is their palette, and when she's given carte-blanche to do whatever she likes within the little house at Lantern Hill, she takes full advantage of it.

This book is all about how people, like plants, thrive in the proper soil, and for humans it's when we find our ideal environment, niche and tribe, and are free to work out our deepest purposes.

So I guess the theme sure isn't, 'Bloom where you're planted,' but there are plenty more which can probably be applied to each character.

One of Jane's is definitely, 'The thing you're dreading may turn out to be the best blessing ever.'

Andrew's might be, 'Go out on a limb and see what happens,' or, 'You have nothing to lose.'

For Robin, 'If life offers a second chance, grab it with both hands.'

And for Grandmother, 'Hold life loosely, or you may loose what you cling to with that white knuckled grip.'

Perhaps the best lesson of all is that enthusiasm is contagious. It's such a charming father/daughter tale, and the mutual benefits are immense. Jane makes it her mission to provide the warm, homely comforts she believes Andrew lacks in his bachelor lifestyle. In return, through listening to his great takes on geography, history, religious studies and current affairs, she discovers she actually loves the school subjects she'd assumed she hates.

If you're a sentimental reader like myself, read it if you can.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

May 10, 2021

'Prince Caspian' by C. S. Lewis

Or 'The One with the Hard-Done-By Prince'

Some minor spoilers lurk below the summary, so beware.

I admit I felt resistance coming into this one, after the impact made by The Horse and his Boy. This book generally ranks low when it comes to the Narnia series, and rarely seems to be anyone's top favourite (similar to Harry Potter & the Order of the Phoenix, I guess.) I remember falling asleep during the Prince Caspian movie, because it seemed so drawn out. But to enjoy a book, the first step is to get stuck into it. So here goes.

The Pevensie kids are all a year older, and waiting on a station platform for their trains to boarding school. Suddenly they're tugged by some invisible magic to the ruins of Cair Paravel. They've returned to their old stamping ground in Narnia, but apparently hundreds of years have lapsed since they reigned there. It's now a derelict castle on an island. It turns out they've been supernaturally summoned to help with a dire situation, like living ghosts. Unfortunately, plenty of readjustment is necessary, since they've arrived not in their regal Narnian forms, but their British school kid states when they're least equipped to be of any help. And we meet Prince Caspian, the boy who is current heir to the throne, but thwarted by his wicked uncle.

What I appreciated more than before.

1) The different attitudes of Caspian's two dwarf supporters. Honest Trumpkin is very much the skeptic, who refuses to consider there may be a grain of truth to stories of Narnia's golden past. In his view, we can only trust what we can detect with our own five senses; a limited perspective indeed. And zealous Nikabrik is prepared to give his allegiance to absolutely anybody willing to drive out Miraz, their bitter enemy, whether it's Aslan or the White Witch. This makes Nikabrik a dangerous ally. Yet as the others realize, it's his desperate circumstances that bring out the worst in him. If not for the looming threat of civil war, Nikabrik may have remained a harmless, occasionally grouchy guy. Those of us living in western, modern times might do well to reflect that perhaps our shadow sides have simply remained dormant. An easy, peaceful era is no excuse for complacency.

2) We get one of the greatest Edmund moments! He decides to suppport Lucy this time, when she claims to have seen Aslan, even though all evidence indicates she's delusional. But he has learned his lesson from his treatment of her in the past. In this case it means going out on a limb, since he can see nothing at first and must rely completely on her call. Hooray, you go, boy!

3) It's fascinating to consider why only Lucy can see Aslan at this point, and none of the others. One possibility is that Aslan chooses Lucy alone to reveal himself to, but the progression of the story indicates this isn't the right answer. It appears the spiritually receptive, humble and pure of heart simply have the most sensitive antennae. Aslan is there the whole time. The self-professed smart folk, over-thinkers and worldly among us just need to tune in.

4) We meet the brave Reepicheep and his army of fellow mice, who steal the show. Especially when poor Reepicheep loses his tail, and all the others would choose to sacrifice their own pride and honour rather than have their captain go without. In Aslan's opinion, their affection and loyalty trump Reepicheep's showy vainglory, and gets his request granted.

5) The fact that such a vast underground world of good talking animals and magical beings exists in hiding from the tyrant Miraz, including a giant or two, is a comforting notion. Even Caspian has no idea until he makes the first step to cut his family ties.

6) Lewis' description of the living trees, who seem to move fluidly between their woodsy and human states, is wonderful! He really gets that subtle magic on the page, and it extends to what they eat.

What I wasn't a fan of this time round.

1) The pace is slower at times than the other books, and I think this may be because it's a bridging book, between two very different time periods. It's interesting in it's own right, but a fair chunk of backstory must be told, which puts the brakes on the action. Even though the chapters recounting Caspian's childhood revelations are told with immediacy, they are still backstory to the Pevensies, and I think it shows.

2) Maybe Nikabrik actually had a point. If you're in Caspian's position and blow the magical horn out of sheer desperation, don't assume help will arrive promptly. There's lots of bungling, guessing, second guessing, arguing and time-wasting before the help actually arrives. (I'm aware that some readers may consider this a story strength, rather than a weakness. But it had me rolling my eyes.)

3) Aslan tells Peter and Susan this will be their last visit to Narnia because they're getting too old. I'm not sure I like this spin from Lewis, considering the rock solid spiritual reality on which their life in Narnia is based. It suggests it's all an ephemeral, Puff the Magic Dragon type of make-believe which they're nearly grown out of, and totally undermines the allegorical fantasy world he's taken such care to set up. It also contradicts what Aslan tells Lucy, that whenever she encounters him, she'll find him bigger rather than smaller, because she's growing into a more deep and mature awareness.

Some great quotes.

Lucy: I do wish now that we're not thirsty we could keep on feeling as not hungry as we did when we were thirsty.

Edmund: Oh, don't take any notice of her. She's always a wet blanket. (Talking about Susan.)

Aslan: To know what would have happened, child? Nobody is ever told that. But anyone can find out what will happen.

Aslan (to Lucy): Go and wake the others and tell them to follow. If they will not, then you at least, must follow me alone.

Aslan (to Susan): You have listened to fears, child. Come, let me breathe on you. Forget them. Are you brave again?

Aslan (to Prince Caspian): You come of the Lord Adam and the Lady Eve. And that is both honour enough to erect the head of the poorest beggar, and shame enough to bow the shoulders of the greatest emperor on earth. Be content.

Stay tuned, because next up will be The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

May 2, 2021

Wonderful Doppelganger Stories (Literary Look-Alikes)

What a recipe for mayhem and confusion. Legend tells us that many people have a double somewhere, but because the world is such a large place, they rarely cross paths. Doppelgangers, of course, are total strangers who share no genetic make-up but for some freakish reason, look exactly alike. As you may imagine, authors and storytellers have had a field day with this premise. Here are some great examples I can think of.

Tom Canty and Prince Edward

The social chasm between these boys could not be wider. One is a slum kid and the other is the only son of King Henry VIII and heir to the throne of England. Both 10-year-olds think it would be a fun gag to swap clothes for a day, but their prank backfires big time when all the adults assume they've turned crazy and refuse take them back where they belong. It's pure entertainment from Mark Twain, but he does get us pondering the way in which people are socially conditioned to live up or down to expectations. (See my review of The Prince & the Pauper.)

Shasta and Prince Corin of Archenland

Technically, these two shouldn't really count as they turn out to be identical twin brothers and not true doppelgangers at all. Yet they've been separated since babyhood, and as far as they are concerned, they are total strangers who are mixed up by some very important people. Shasta, a humble runaway, overhears some royal intrigue that would never have reached his ears if King Edmund and Queen Susan of Narnia hadn't insisted on mistaking him for their young friend Corin from a neighbouring kingdom. In this case, being identical has some crucial repercussions for entire nations. (See my write-up of The Horse & his Boy.)

John the Historian and Jean de' Gue

After a chance meeting in a public place, Frenchman Jean entices British John into getting drunk, so he can swap their clothes and tick off across the Channel with John's ID. John has to face the mess Jean left behind him at home in his own chateau. For various reasons, going along with the masquerade for the sake of Jean's family seems the correct and moral thing for John to do. The question is, does he simply imagine lovable traits in Jean's family members just because he's not so close to some flammable situations which have been brewing for decades? Or are they really there? Some chilling suspense from Daphne du Maurier. (My review of The Scapegoat is coming soon. )

Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton

If I had to make a choice, these two are my favourite doppelgangers. Charles is the nephew of a corrupt French nobleman, and Sydney is an unfettered and depressed English lawyer. Both are in love with beautiful Lucie Manette, but she loves just one of them. Sydney, the rejected suitor, resolves to stay devoted to Lucie all his life, for he can't stop loving her. But when the crunch comes, can he orchestrate a total swap with Charles at a crucial moment, making the ultimate sacrifice to benefit Lucie and her family? It all hinges on their physical resemblance. This is one of the most breathtaking and romantic French Revolution tales. (See my review of A Tale of Two Cities.)

Yakov Golyadkin and Golyadkin Junior

This one is a creepy tale from Fyodor Dostoevsky. Golyadkin is an anxious and inept bureaucrat who bumps into his double one night, on the way home from an awkward party. The other guy, who chooses to be called Golyadkin Junior, has all the charm and polish which the original lacks. They start a warm relationship as friends who believe they can mutually benefit each other. But all too soon it dawns on the first Golyadkin that his sinister doppelganger is steadily hijacking his life. This tale has an interesting psychological twist, as readers are challenged to decide whether there was ever really a dopperganger at all, or if one pathetic man was simply having a mental breakdown. (My review of The Double coming soon.)

John Harmon and George Radfoot

It's another Dickens example, and I'll take care to tread carefully and give away no crucial plot points. It's enough to say that one of these two is honourable while the other is open to bribes and corruption. One is a man of the sea while the other prefers solid land. Most importantly, one lies drowned at the bottom of the Thames and the other does not. But even so, they keep getting mistaken one for the other. (See my review of Our Mutual Friend.)

Not only are doppelganger stories great fun to read, but they also have potential for some excellent one liners such as the following.

1) I make it a rule never to be surprised by anything in life; there is no reason to make an exception now. What will you drink? (Jean to John)

2) I would ask that I might be regarded as a useless (and I would add, if it were not for the resemblance I detected between you and me), an un-ornamental piece of furniture. (Sydney to Charles)

3) Why are you in such a hurry? I say: we ought to be able to get some fun out of this being mistaken for one another. (Corin to Shasta)

How would you handle it if you met yours? I've certainly spotted doppelgangers of friends and family members walking around in the big wide world, but never my own. I'm sure I'd find it a bit creepy, but as a kid, I always thought the novelty would be overwhelming, and I'd want to play tricks, like Tom, Edward, Shasta and Corin. And all these decades later, I think my reaction would still be the same. Just imagine the fun! Which are your favourites?

The Vince Review

I invite you to treat this blog like a book-finder. People often ask the question, "What should I read next?" I've done it myself. I try to read widely, so hopefully you will find something that will strike a chord with you. The impressions that good books make deserve to be shared.

I read contemporary, historical and fantasy genres. You'll find plenty of Christian books, but also some good ones from the wider market. I also read a bit of non-fiction to fill that gap between fiction, when I don't want to get straight on with a new story as the characters of the last are still playing so vividly in my head. ...more

- Paula Vince's profile

- 108 followers