Paula Vince's Blog: The Vince Review, page 12

August 24, 2023

'From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler' by E. L. Konigsburg

Since its first appearance over 50 years ago, The Mixed-up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler has gained a place in the hearts of generations of readers - and has rightly become one of the most celebrated and beloved children's books of all time.

MY THOUGHTS:

Phew, I can finally tick off this super-long title. (Just to be clear, I'm referring to the title being super-long, not the story itself.) For years I've seen this Newbery Award winning middle-grade novel from 1968 recommended far and wide. I finally borrowed a library e-book and found it both thought-provoking and very cute.

Claudia Kincaid decides to run away and live for a short time in New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art, because it's such an elegant and important place in which to hide. She coerces her younger brother Jamie to join her, since he's a fiscal wizard who has saved loads of pocket money. Their simple mission to avoid detection soon becomes a compulsive quest to discover the origins of a stunning angel statue. Claudia isn't sure what appeals so strongly to her, but trusts that finding out will be an epiphany. All she and Jamie know is that it came from the collection of a wealthy lady named Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler who sold it to the museum for $225.

It is the elderly and wise Mrs Frankweiler who deduces what drives Claudia so hard to find the answer, and what manner of mindshift will really make a difference in her restless heart.

It wouldn't be such a fun read without the witty and evolving rapport between Claudia and Jamie, who forever banter but are truly in sync. They are now up among my favourite storybook sibling duos, and Konigsburg's illustrations reinforce what a lovable team they make. Claudia is a straight A student full of head knowledge, and as the eldest, a bit of a know-it-all. But Jamie is a very pragmatic 9-year-old, and I love how Claudia defers to him in all their economic decisions.

The museum is an atmospheric setting. It housed over 365 000 works of art way back when this book was published, which means the Kincaids would have to look at 1000 exhibits per day to see it all within a year. When Claudia and Jamie settle down in an antique bed on their first night in hiding, we are told, 'The silence seeped from their heads to their soles and then into their souls.' Sounds a bit spooky to me, but I like it.

When I read a couple of other reviews on Goodreads, one lady ranked it low and remarked that the modern kids she knows wouldn't grasp or appreciate the introspective and motivational messages that kids of the late 1960s apparently did. But as far as I'm concerned, the book is as great as it ever was, and using her own reasoning, if anything deserves to have stars lopped off, it should be our 21st century culture, if it discourages contemplation in juvenile fiction.

🌟🌟🌟🌟

August 17, 2023

'Charlotte Sometimes' by Penelope Farmer

A time-travel story that is both a poignant exploration of human identity and an absorbing tale of suspense.

It's natural to feel a little out of place when you're the new girl, but when Charlotte Makepeace wakes up after her first night at boarding school, she's everyone thinks she's a girl called Clare Mobley, and even more shockingly, it seems she has traveled forty years back in time to 1918.

MY THOUGHTS:

This is a re-read from my childhood. Silent reading sessions were the best, and the details of this story were sketchy. The fact that it's a time slip story stood out most, for I love those.

Feeling lonely and awkward, Charlotte drifts off to sleep on her first night at boarding school in a shared dorm room. She wakes up next morning and finds herself in the same room with oddly different furniture. In the opposite bed is a little girl who is adamant that Charlotte is, in fact, her own sister, Clare. It is not the next morning after all. Charlotte has been swept back 40 years into the past.

This is a doppelganger yarn and time travel tale rolled into one. At first it chops and changes. Charlotte is sometimes her own self in 1958, and other times assumes Clare's identity in 1918 while World War 1 rages in the background. The same thing happens to poor Clare, although we never read that side of the switch. Eventually, circumstances transpire to keep them both permanently where (or rather when) they shouldn't be, unless they come up with a solution.

All sorts of school politics happen in both time periods. Charlotte is thoughtful and intuitive, which people don't always notice through her sedate front, although I find her astonishingly slow on the uptake at times. (Hooray Charlotte, at last it dawns on you that women tend to change their surnames when they get married.) Emily Moby, her 'sister' in 1918, is defensive and non-conformist, possibly one of the story's most memorable characters. This little girl won't be pushed around by anyone.

The details of the war era makes the earlier of the two settings the focal point. All sorts of desperate cost-cuttings and rationings become part of everyday life, including the sacrifice of flower gardens for vegetables. When Charlotte and Emily are billeted out with the Chisel Brown family of Flintlock Lodge, the grievous loss of their son Arthur in the trenches of France spreads to impact even the girls, who have never met him. (Whoa, he's a haunting character, in more ways than one!)

The story is not perfect. The premise itself is strained, since the bed portal only works with Charlotte and Clare, regardless of whoever else sleeps in it throughout the years. Even the characters remark on the crazy unlikelihood of this, so Farmer herself must have realised what a stretch of credulity she was creating. It may seem an unfair thing to mention, considering the same implausibility applies to all time slip stories to some extent, but this one seems particularly clunky.

Penelope Farmer's writing style sometimes makes me pause mid sentence to wonder, 'Whatever next?' She matches emotive qualities to simple objects in a way that's a bit jarring. For example, how can a cake of soap have a 'glum and parsimonious' smell? That's super specific. In another instance, chubby Mrs Chisel Brown speaks in a 'fat' voice. Come on, how can a person's voice match their physical shape? It's obviously stylistic, but jolts me out of the story's flow to roll my eyes at Farmer's weird technique.

I think the story is strongest if we read it as an analogy that shows the strain of maintaining masks in our own lives. The Charlotte/Clare swap reveals the exhausting juggling act of trying to be different things to different people, rather than just our own straightforward selves. We can take that on board in this story without the fascinating benefit of time travel.

Overall, this is quite a fun time slip story, though I think Penelope Farmer could have tied up a few loose ends and revealed where 40 years had taken several different characters. I'll give it the extra half star for Emily and for Arthur, who lived and breathed on the pages, even though he's a dead character.

Oh, and check out the song by The Cure.

🌟🌟🌟½

August 9, 2023

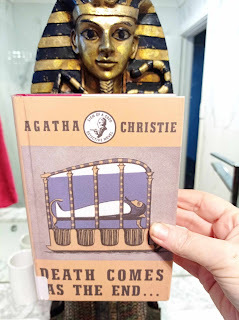

'Death Comes as the End' by Agatha Christie

In this novel of anger, jealousy, betrayal and murder, the Queen of Mystery transports us back to ancient Egypt 2000 B.C. where a priest’s daughter, investigating a suspicious death, uncovers a wasp’s nest of jealousy, betrayal, and serial murder.

MY THOUGHTS:

I'd just hopped into a bubble bath with an Agatha Christie mystery expecting 1930s Britain as usual, but got Ancient Egypt instead! Whoa, that took me totally off guard but I decided to flow with it. It seems that spurred on by her Middle East field observations with her archaeologist husband, the Queen of Crime challenged herself to create a detective story with a radically different setting, while retaining her hallmark for murders on family estates with assorted motives between an extensive cast. The foreword of my library book shows she was encouraged by her friend, Professor Stephen Glanville, who sent her heaps of literature.

I've often thought about the potential pitfalls of historical research for authors who are used to writing contemporary fiction. My husband always insists that any plot can be tailored to fit any time period and setting. I believe Agatha Christie aimed to prove the same thing in her own way, and did a pretty good job.

It's some time around 4000 BC and Renisenb, a young widow, has returned to her family home after eight years away. She's relieved to find that her brothers, sisters-in-law, granny and father haven't changed at all. Time tends to stand still at her family home, which comforts her. Yet Hori, the young estate manager, challenges Renisenb that this is not the case. He's certain that turmoil brews beneath the appearance of family unity which needs just one spark from outside to make it all combust.

This spark comes in the form of Nofret, their elderly father's hot new concubine, who turns out to be an artful troublemaker and makes no friends for herself. When Nofret is discovered dead on a walking trail, it appears she accidentally fell from another path high above, yet everyone tacitly agrees that convenient conclusion is a copout. The big question is, who resented Nofret enough to push her? Could it be any of Renisenb's brothers; gentle, compliant Yahmose, Sobek, the inept grumbler, or Ipy, the mutinous and spoiled 16-year-old? Perhaps Henet, the two-faced and calculating poor relative, knows more than she's letting on.

When it appears that Nofret's vengeful spirit is at large, trying to get even with every single member of her hapless husband's family, it's clear something must be done.

The story delves into the masks people wear, yet in this context, the wise Hori likens them to false doors in pyramids and tombs. Sadly, I wasn't convinced by the revelation of the murderer. Usually Agatha Christie's unexpected twists work fine, but this one feels forced. Even though she left a characteristic hint to justify the great reveal, I didn't buy it. The chasm between what we see of the murderer and what we get is simply too huge to swallow, and I can't believe for a moment this person would snap to the extent of embarking on the reckless rampage that ensues.

That's sad really, because other than that, I enjoyed the visit to Ancient Egypt.

🌟🌟🌟

August 2, 2023

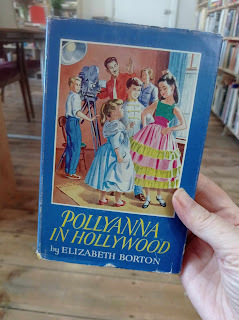

'Pollyanna in Hollywood' by Elizabeth Borton

MY THOUGHTS:

This is the seventh Glad Book. Jimmy has been commissioned to build another big dam in Inyo County, California. They've rented a house in nearby Hollywood, where Pollyanna and the kids can enjoy the good life while he comes and goes. The Pendleton family strike up a friendship on the beach with Happy Bangs, a melancholic silent comedy star who introduces them to the glittery world behind the scenes where movies get made. Meanwhile the kids make some interesting friends. Junior develops a passion for cameras and filming, and Judy for dancing and choreography.

Elizabeth Borton takes the baton from Harriet Lummis Smith. She was born in 1904, lived until 2001 and one of her other books won the Newbery Medal in 1966. Judging by this Glad Book alone, Borton's excessively detailed style of writing is no longer what we're used to in the twenty-first century. Some readers may claim that it doesn't move the story forward but rather drags it down. For example, Pollyanna and Jimmy treat Jamie and Sadie to dinner at a Mexican restaurant, and descriptions of the decor and staff linger for pages.

Her prose could be likened to painstaking brushstrokes which allow no room for us to fill in details with our own imaginations. These slabs of excessive description bothered me a bit, but I think the key to enjoying this book is just to chill out with the slow moments and be content going nowhere for a while. Perhaps it's even the sort of meditative style that does us good, which is mostly found in older books now.

Yet having said her writing style tends to be slow, Borton's plots themselves can move insanely fast. Meetings, marriages and movies happen in a snap. Another new friend of theirs, Maude Cravath, turns from down-and-out saleswoman to movie star within a few short weeks, I kid you not. Were motion pictures ever really made so quickly in the 1930s? Even if they were that slapdash, how did she build her fan base so fast, considering the red carpet event at which she shone was the debut night? It's pretty unbelievable.

One thing I did appreciate is how yet another character, Myra Britton, decides she's content to have played lead role in one feature film to prove to herself that she can, and now she's done. She rejects further offers from producers. 'No, I have done one piece of almost perfect work. I could never do better. So I stop. I do not care for anti-climaxes. I have done well. It is enough.' Later, Pollyanna agrees with Myra's courage and conviction to retire before her ball really starts rolling. 'It would be a pity to follow that inspired piece with one less noble and less finished.' You rarely find such a refreshing attitude in our era, where celebrities struggle to maintain their platforms for as long as possible.

But we have to take positive dated attitudes with the negative. 'Junior was learning the lesson that boys must learn - to be strong in the face of grief. Girls may cry but boys must hold back the scalding tears as unmanly.' What a load of harmful nonsense.

In other family news, Uncle John is researching and writing a book about American folklore, which means plenty of travel for him and Aunt Ruth. Jamie has signed a contract with a motion picture studio to write scenarios for them, with a stupendous salary he couldn't possibly refuse, so he, Sadie and their little boy (who they nickname Jamsie) head to Hollywood too, to live close to Pollyanna's family. But alas, Jamie hits a slab of writer's block and becomes even more touchy and harder to live with than normal. As his loved-ones know full well, it's tough on a chap whose only source of self-worth comes from his ability to write. Perhaps he's secretly irritated that his stepfather is treading on his turf.

Borton's Nancy is a bit of a grumblebum, but in all fairness, Smith started it. Pollyanna is still an energetic sticky-beak who changes lives while others simply ponder good ideas they never implement. Jimmy is still dependable, humorous and dare I say sexy. The kids are growing up and developing distinct characters. My bottom line is that this book is fun for bringing us more stories about the Pendletons and Carews, but in all honesty, it's not as engrossing as the first six, by Porter and Smith. Any book that manages to be both speedy and snail-paced in the worst ways strikes a bad note, and I'd nod along with any reader who calls it a chore.

Anyway, next up will be Pollyanna's Castle in Mexico.

🌟🌟

July 26, 2023

'Adam Bede' by George Eliot

A bestseller from the moment of publication, Adam Bede, although on one level a rich and loving re-creation of a small community shaken to its core, is more than a charming, faultlessly evoked pastoral. However much the reader may sympathize with Hetty Sorrel and identify with Arthur Donnithorne, her seducer, and with Adam Bede, the man Hetty betrays,it is George Eliots's creation of the distant aesthetic whole - the complex, multifarious life of Hayslope - which so grips the reader's imagination. As Stephen Gill comments: 'Reading the novel is a process of learning simultaneously about the world of Adam Bede and the world of Adam Bede.'

MY THOUGHTS:

For so long I allowed the bleak sounding blurb to influence my decision not to pick up this book, but the fact that it took its earliest readers by storm, selling over 5000 copies within a fortnight, convinced me I was being too hasty. If these Victorians were onto something good, I didn't want to miss out.

This was George Eliot's debut novel, making her a pioneer and master of psychological fiction that delves into the nitty gritty of people's motivations. It also establishes her as a novelist who focuses on 'low life' and humble folk. Eliot's fondness for normal, working class people shines through the pages. I believe she does for them with words what artists such as Rembrandt and Vermeer did with painted images of noble-hearted commoners just getting on with their day.

The setting is the fertile pastoral village of Hayslope and the year is 1799, so we get to witness the turn into the nineteenth century. The split between the established, complacent Anglicans and the enthusiastic, full-on Methodists is wide and controversial. A type of feudalism exists in English villages, and of course, the political backdrop is war with France.

Decisive, hard-working and extremely principled young carpenter, Adam Bede, is devastated to discover two people he loves and trusts most in the world having an illicit affair. One is Hetty Sorrel, the pretty girl Adam intends to propose to, and the other is Arthur Donnithorne, the boyish young squire whose family owns the land on which the Bedes and several others live. 20-year-old Arthur is a favourite with the whole community, who all eagerly anticipate the demise of his crusty old grandfather so he can become landlord.

We readers, who are granted access into Hetty's and Arthur's headspaces as well as Adam's, sense the bombshell coming and grit our teeth waiting for the fall out. Hetty is the early nineteenth century version of a material girl, self-focused and shallow. And Arthur has so internalized the notion that he's a good guy who always falls on his feet, he can't help vacillating between guilt and desire when it comes to forbidden fruit.

But back around 1800, mistakes of immaturity were not merely awkward but catastrophic. Inevitably, their forbidden romance brings down a ton of trouble on many people. Since social structure is rigid, these two kids are playing with fire.

I really like the potential 4th corner of this lovers triangle, preacher girl Dinah Morris, whose eyes were 'shedding love rather than observations.' She acts out of a servant heart, quietly making the world a better place. This girl genuinely seems to consider the world's dirty work a refreshing privilege. I love how Dinah's aunt remarks that their comfortable family is probably not 'needy' enough to receive a longed-for visit from her niece.

Don't even get me started on the potential 5th corner, Adam's gentle and dreamy brother Seth, always in his brother's shadow and seemingly quite content to be there. Sometimes it seems everybody in this story is deeply in love with somebody who happens to be looking elsewhere. Forget the love triangle, this is a love hexagon.

I've got to say, I willingly immersed myself in all the drama. Eliot's friend, Mrs Carlyle, reputedly said, 'Its as good as going to the country for one's health. I found myself in charity with the whole human race when I laid it down.' I tend to agree with her. Secondary characters such as the outrageously misogynistic Bartle Massey and blunt Mrs Poyser help make it a fun and lovable read.

Eliot's prose is beautiful to read. And the contrast between inflexible Adam and indecisive Arthur makes a fascinating study. Both young men need to make course corrections to come to some sort of middle ground, although neither realise it from the start. I consider it a sort of bromance that went rocky for a while.

It's the sort of hefty English classic that immerses us deep into the psyches of these characters by shining light into the minutiae of their days, whereas modern authors are often told to scrap anything that doesn't directly drive the plot forward. The evening of Arthur's 21st birthday party alone takes up a full five chapters! Books are faster moving these days. We can't always add to our stories all the cool, psychological nuances Eliot was famous for, because we aren't allowed to!

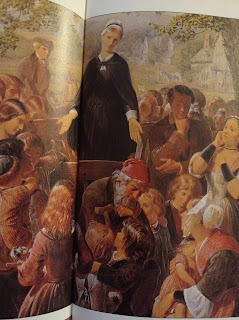

But hey, at least we still have access to Eliot's books. I heartily recommend this one. Within these pages both Adam and Dinah are committed to making the world a better place, in their own small way, for having passed through. And their author, Eliot, did the same thing in her special way by writing this novel. I'll finish off with this coloured picture in a book of mine which I believe evokes perfectly the background and time period of the novel, and also Eliot's conception of Dinah Morris.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

July 19, 2023

Some Mini Reviews for July

'Life in Five Senses' by Gretchen Rubin

I've long agreed with the theory that human beings give our five physical senses too much sway at the expense of the far vaster, more formative spiritual world which shapes things behind the scenes. Advice we hear to 'get out of our senses' is wise in many instances.

Yet in spite of their enormity, we tend to zone out too much, taking our five senses for granted and allowing potentially meaningful moments to pass us by. That is Gretchen Rubin's premise anyway, in this manifesto that urges us to start paying way more attention to what we see, hear, touch, taste and smell.

She is one of the authors whose new books I always aim to get hold of, since I enjoy her fresh take on everyday actions we can all do. Ever since I read The Happiness Project, Rubin's life enhancing suggestions always strike me as reasonable hacks which cost nothing.

What's more, her books enable armchair travel to one specific place. Since I doubt I'll ever manage to visit New York City, I like what I see of the Big Apple in her writing. In this book, Rubin makes the most of daily visits the Metropolitan Museum of Art, since she lives within walking distance.

I recommend you read it. We can surely embellish our lives in easy, self-aware ways. Since finishing this, I've done more active listening, studied the nuances of famous works of art, enhanced my Spotify playlist, unashamedly indulged in perfumed candle sniffing and considered the timeline of tastes that runs throughout my life. (I'm afraid as a kid I considered Kraft mac and cheese and Semolina drizzled with honey my favourite meals. No nostalgic memories of any dishes my mother cooked to perfection.) I've stroked my cat's fur and asked my son to locate his fidget spinner. And I've made plans to add more sensual herbs to the rosemary, lavender, mint and basil already growing out on my deck.

Just for the record, she brings to our memories a few internet viral sensations. Remember that controversial dress? I now see it as black and blue, although I think I saw white and gold in the early days. And I always hear 'Yanni' and never 'Laurel' in that divisive hearing test. How about you?

After reflection, I've come to think a lovely purring cat satisfies four of the five senses, with the exception of taste.

🌟🌟🌟🌟½

'Gentian Hill' by Elizabeth Goudge

This is essentially a love story, often long distance, between two young people during the time of the Napoleonic Wars.

15-year-old Anthony O'Connell is a midshipman who impulsively deserts ship in Torquay, unable to bear the horrific, squalid lifestyle at sea on the heels of a genteel upbringing. He decides to take on the alias 'Zachary' from that time forward.

Meanwhile, 10-year-old Stella Sprigg lives with her step-parents at Weekaborough Farm. She was rescued from a horrific ship explosion as an infant and her mysterious, prestigious past comes to light during the course of this novel. (I find the revelation is quite heavy handed, with no surprise element for us readers.)

When these two, each bearing names they weren't christened with, come together, they recognise each other as kindred spirits, or twin souls or two sides of the same coin, and even have some ESP line running between them. I can't count the number of times Goudge implicitly suggests the noble blood flowing in Zachary's and Stella's veins makes them a superior, ultra-sensitive breed of people. Stella in particular is depicted as a wonder child. I'm sure if Stella slept on a dozen piled mattresses like that fairytale princess, she'd definitely feel a tiny pea underneath.

The plot partly concerns how Zachary musters courage to resume the naval career he ran away from. The fact that he considers himself cowardly on account of his conscientious objector stance irked me too. Some uncaring relative set him up on the ship to get rid of him at the outset. He never once chose that lifestyle for himself, so I regard his initial escape as proactive rather than fleeing his destiny. Life is too short to return to what we despise, simply to prove a point. Maybe if more boys deserted, there might be fewer wars.

Clearly, this is not my favourite Goudge novel. But there are several lovely word pictures of rural British life, and cool animal characters. And hey, I've found out how creepy mandrake roots really look. Put it this way, the Herbology lessons with Madame Sprout in Harry Potter stories are no exaggeration. Look them up and see for yourself.

🌟🌟½

July 12, 2023

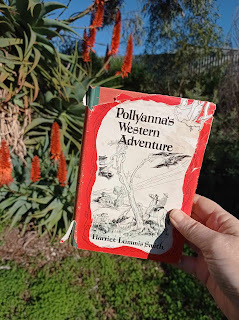

'Pollyanna's Western Adventure' by Harriet Lummis Smith

MY THOUGHTS:

This sixth Glad Book is one that my mum retained from her youth, so I'd read and loved it years ago. Great fun to revisit it again now.

Jimmy is pressured at work to accept a two year assignment building a dam out in the wilderness. He sadly refuses because he doesn't consider it'll suit a family man... until Pollyanna convinces him that they'll make it work because they'll all go with him for the duration. 'He'd lived with her for twelve years without knowing she was ready to follow him to the world's end.' Aww, I love that. So they rent a house near a primitive town called Deer Creek, hire an adventurous young woman named Dorothy Blythe to help teach the kids, and set off.

I've always enjoyed stories where characters turn their backs on civilisation. It appeals to some minimalist, solitude-loving part of my nature without actually having to do it myself. The cosmopolitan Aunt Ruth expects to see Pollyanna return home as a bone-weary, broken-down drudge, old before her time, while Jimmy suggests the seclusion and fresh air may prove a fountain of youth. Their house has no plumbing, but a water pump in the yard, and presumably a long-drop toilet. To quote the Gilligan's Island theme song, it's 'primitive as can be.'

Yet there are enough people out in the Deer Creek community to make for a good story, including three young fellows making moves on Dorothy, who turns out to be a consummate flirt, although that passed Pollyanna's notice during the interview process. Dorothy is a man magnet in the middle of nowhere, while lots of urban girls can't attract one, even in a big city.

One of my favourite characters is Luke Geist, a 24-year-old invalid who suffered an accident that leaves him flat on his back in bed. His friendship with Pollyanna shows her at her best. It's very cool that a mid-thirties wife and mother will take initiative to reach out to a single guy ten or twelve years younger who is known for being a bit caustic. But she swoops in where many women in her position might fear to tread, (I doubt I would dare), and we get one of the best platonic friendships of the series.

Smith's writing is quite spare. She never divulges the nature of Luke's accident; only drops hints that it happened when he was about 19 years old, cutting him down at an active and impressionable age. I might've assumed a writer is obliged to provide backstory for something so pivotal, but it turns out leaving the possibilities open to our imaginations is even more powerful. 'Less' is 'more'. Luke's story ends on a positive note with hints that it may contain romance.

The other interesting thread is Pollyanna's mobile library, which she sets up to help the hardworking folk in the valley 'forget the monotony of their daily toil in vicarious flights of imagination.' I love the broad attraction of books, which we don't necessarily see in our own culture where they are widely available. Many people I know claim to rarely read books, so perhaps scarcity creates an appeal.

However, Pollyanna exerts iron control over her selection. Whenever she receives donations of books in the post from friends and family, she chooses to burn those which don't tick her boxes. Smith refers to 'a number of private little bonfires.' Hmm, this makes Pollyanna a book banner, on her own small scale.

I haven't quite figured out where I stand on the debate. On one hand, she's entitled to quality control since the library is her own brainchild, yet on the other, banning books artificially restricts other people's reading lives and denies them an opportunity for deep, honest reflection to work things out their own way. Having come across extra-vigilant school librarians banning books for the most nitpicky reasons, I tend to consider Pollyanna's behaviour crosses a line into literary despotism. That's not to say I've never 'screened' books with others in mind, especially for homeschooling. It's an interesting debate.

Sadly, Harriet Lummis Smith's contribution to the series ends here. This book was first published in 1929 and she lived until 1947, so perhaps she decided four was a big enough contribution from her. I enjoyed her style and conception of the characters; a warm-hearted, if somewhat nosy Pollyanna, a steady, witty, undeniably dishy Jimmy, and three lively kids. What's more, she brings to life 1920s mindsets and shows what never changes. (In this book, Pollyanna rolls her eyes at Dorothy and wonders, 'was the younger generation always like this, so sure of itself and patronisingly superior when experience protested?')

The slack will be picked up by the next author, Elizabeth Borton, so we'll see how that goes. Next up will be Pollyanna in Hollywood.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

July 5, 2023

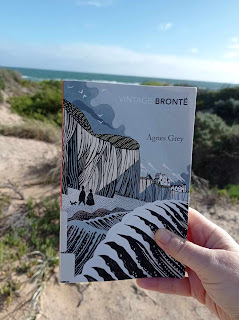

'Agnes Grey' by Anne Bronte

Drawing heavily from personal experience, Anne Brontë wrote Agnes Grey in an effort to represent the many 19th Century women who worked as governesses and suffered daily abuse as a result of their position.

Having lost the family savings on risky investments, Richard Grey removes himself from family life and suffers a bout of depression. Feeling helpless and frustrated, his youngest daughter, Agnes, applies for a job as a governess to the children of a wealthy, upper-class, English family.

A tale of female bravery in the face of isolation and subjugation, Agnes Grey is a masterpiece claimed by Irish writer, George Moore, to be possessed of all the qualities and style of a Jane Austen title. Its simple prosaic style propels the narrative forward in a gentle yet rhythmic manner which continuously leaves the listener wanting to know more.

MY THOUGHTS:

Here is the final Bronte novel to make my re-reads complete. Essentially, Anne has fictionalised her own experiences working as a governess, with the exception of the romance thread, which is widely regarded as a wishful projection on her part, since she remained single throughout her young life. Perhaps the wonderful Mr Weston is based on Anne's father's curate, William Weightman, traditionally believed to be Anne's crush. If so, he must have been one heck of a guy. But of course poor Anne left no records for clues.

The two sections of the book, characterised by Agnes' employment with separate families, strike me as belonging in two different books. I found the first part face-palmy and the second part quite enjoyable, so I'll discuss them separately.

1) Her employment with the Bloomfield family.

Agnes launches out from a sheltered household with no idea that some kids can be malicious brats who thrive on making others miserable. It turns out 7-year-old Tom is bossy and smug while 6-year-old Mary Ann is stubborn and obtuse. And their father is an autocratic jerk, while their mother refuses to listen. So Agnes' hands are tied.

The Bloomfield kids run rings around Agnes because they know they wield power to do so. It's the same old story we're all familiar with. The Bloomfield parents forbid Agnes from punishing their darlings, yet still expect her to maintain some semblance of control in the schoolroom. Similar struggles remain to this day. It's probably one of the ultimate deadlocks throughout the history of education. Parents are convinced that they know the nuances of their own kids better than any teacher, yet teachers feel they may get along better without the undermining of parental interference from people who don't realise their own blind spots. And when this situation happens beneath the same roof, it sounds like a tinder box for trouble.

At this stage of the book, Agnes isn't always easy to sympathise with. She comes to the job as a total novice, yet maintains a superior tone, as if any setback is always her employers' fault. Never once does an, 'Oops, my bad,' type of confession ever slip past her lips. It's human nature to wish to justify ourselves, but her self-righteous stream of complaining gets old quickly. Agnes' own methodology (threats of hell and reactive hair pulling) is dodgy to say the least.

I honestly feel it was a sound move for the Bloomfields to fire her, since she was wasting her own time and theirs, plodding away under some sort of romanticized martyr complex. Hooray, at last somebody had enough common sense to pull the plug. Agnes comments that her purpose in recording all this is 'not to amuse but to benefit.' Yet I don't really get how she thinks she's doing that, unless she's warning other girls considering the career of governess to steer well clear.

2) Her employment with the Murray family.

Yay, with that out of the way, the story starts to gain momentum. Agnes' main pupils are now two teenage girls, Rosalie and Matilda, with whom she develops some rapport. Agnes still never speaks up for herself yet maintains a spiel about how horrible and insensitive all the Murrays are, making her sit on the way to church facing backwards so she gets carriage-sick etc, etc. This girl seems to expect people to be mind-readers and I can't help wondering if the Murrays were simply thoughtless rather than antagonistic in many instances.

I tend to feel more sympathy for the sturdy and sporty Miss Matilda, born into an era which stifled her natural inclination for the great outdoors because she was the 'wrong' gender. I don't blame Matilda one bit for taking out her frustration on the piano keys she was forced to learn to play. Even Anne/Agnes deplores her and calls her a 'hoyden' with its much harsher connotations than the more affectionate 'tomboy' we use today.

The introduction of two clergymen thickens the plot. Mr Hatfield is the supercilious rector and his curate is the plain-looking but warm-hearted Edward Weston. When beautiful Rosalie Murray starts flirting with Mr Weston, who Agnes is secretly head-over-heels in love with, sparks would fly if she dared let them. As it is, the fiery passion is confined within Agnes' own head and heart.

I love how Edward Weston's reputation for kindness and justice precede the man himself. Testimonies filter in from people Agnes trusts; the poverty-stricken cottagers. He's surely the loveliest hero in any Bronte novel, (with the possible exception of Shirley Keeldar's love interest.) He runs rings around any Rochester, Heathcliff or Huntingdon. I don't think this guy gets enough credit for that. He's probably my main reason for boosting my ranking to three stars.

🌟🌟🌟

June 28, 2023

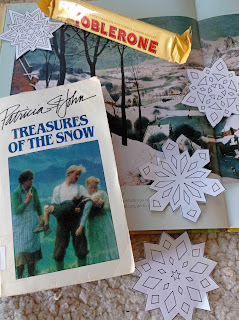

Treasures of the Snow (and other winter reads)

'Treasures of the Snow' by Patricia St. John

What a wonderful old Christian classic set in Switzerland.

Its sentimental title and heavy-handed themes may strike some readers as a bit dated, but I was riveted by the solid substance of the plot and passionate rawness of the two main characters, who are both about 12 or 13 years old.

Lucien Morel attempts to tease little Dani, the kid brother of his neighbour and nemesis Annette Burnier, but things turn horribly pear-shaped. (Conflict on the edge of a precipice rarely ends well!) Dani's shattered leg may leave him permanently lame, and Annette vows to get even with Lucien in any way she possibly can. Meanwhile, poor Lucien deals with the pain of becoming the village pariah for a consequence that was completely accidental.

When Lucien discovers a special talent that may help atone for his bad reputation, Annette's hatred has even more scope than before to wreak havoc on his life. What will it take for her to shake off her bitterness and forgive him? And for that matter, will he be able to forgive her? The soul searching of these two makes an excellent read, although I admit to loving bad boy Lucien a little more than good girl Annette. The dramatic climax draws largely on the terrific Alpine setting.

Young Dani is a very cool character too. Even though he was the scapegoat of their friction, his native cheerfulness is a gift that neither Annette nor Lucien possess. I think it makes him the most emotionally resilient of all. Dani is pretty spoiled, but it's a side benefit of his automatic way of winning hearts. This boy is never preoccupied enough to miss the satisfaction derived from simple things. That's the handiest gift of all, and he's a natural at it.

Apparently there's a more politically correct and dumbed-down version of this classic floating around, ghost written by a lady named Mary Mills. I only found this out after reading a few other reviews of the book. It's said to be hard to identify, since Patricia St. John's name is still the only one on the front cover. That's always been one of my bugbears, but fortunately my secondhand copy is the original. (If the intact descriptions of the scenery weren't a big enough tip-off, the fact the Madame Morel often insults her son, calling him 'stupid' would leave me in no doubt. No modern knock-off would ever leave that in.)

I wish this story had been on my radar while I was homeschooling my kids. I recommend it especially to families who still are. Apart from loving the characters, it evokes the mountain lifestyle, including their soup, rustic bread and 'cheese with holes in it.' (I guess it stands to reason that living in Switzerland, they wouldn't necessarily think of it as Swiss cheese, but simply as 'cheese.')

Just watch out for that modern re-write which every reader I've come across seems to be unanimous in considering more sanitised and soulless than the original.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

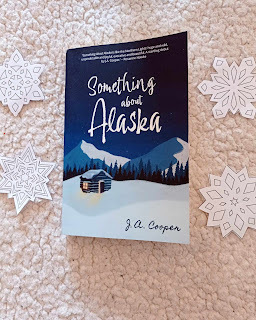

'Something About Alaska' by J. A. Cooper

I looked forward to this one. J. A. Cooper is the director of the Writing and Communication Masters course I'm doing at Tabor College, and therefore one of my teachers. This YA novel is his debut novel. I started it during my summer holidays when it was scorching hot in Adelaide and decided to save it until the winter break. I'm becoming more of a seasonal reader. It seems to enhance the atmosphere when we do our best to match seasons, although admittedly South Australia is nowhere near as cold as Alaska. (Not even close!)

Zac Greene goes to spend Christmas with his estranged dad in Alaska. The intervening years have become an issue though. There's a wedge of awkwardness now he's 14 that wasn't there when he was 10. And Dad seems grouchy and misogynistic from the get-go. Was he always such a know-it-all with a huge chip on his shoulder? It's shaping up to be one of Zac's worst Christmases.

I'll tread carefully from here, so as not to give away too much. Suffice to say Zac's reactive decision to get away involves an encounter with a charismatic local named Stanley, who reveals some of the genuine survival skills necessary for Alaska, which is said to be a magnet for 'wackos' who dare to hope they may tame the elements.

I was behind Zac all the way, having come across guys like his father, Jim, who create chaos despite their best intentions. Yet I wondered whether another type of reader may consider Zac's behaviour too reckless and hasty? In other words, could there be scope for dissension in reading groups? Would we all equally enjoy where the story takes us? With that question in mind, I believe the ending seems inevitable and may elicit nods from the majority of readers that it had to be that way. I would love to see what other readers have to say though.

The descriptions of the fierce, icy setting of Alaska are beautifully crafted and evocative. I paused several times to re-read sentences and take it all in. We are invited to reflect whether Alaska is a cauldron that refines seekers rather than the haven they expect.

Overall, it's a great winter read with a beautiful cover.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

'Hans Brinker and the Silver Skates' by Mary Mapes Dodge

Next we shift to Holland.

This lady was the powerhouse who gave many other turn-of-the-century authors their lucky breaks. Mary Mapes Dodge was regarded as a leader in juvenile fiction throughout the 19th century. As senior editor of the popular Saint Nicholas magazine, which featured stories by up and coming young authors, she published early works by Mark Twain, Louisa May Alcott, Robert Louis Stevenson, Rudyard Kipling and E. B. White, to name a few.

On the strength of Dodge's reputation, I expected to love this famous title of hers. Sadly, I found it hasn't aged well. Some 19th century authors seem to have a gift for remaining engaging and timeless well over a century further on. It strikes me that Dodge wasn't one of them, although many of her proteges were.

Hans Brinker is a noble teenager who struggles to make ends meet. He lives with his younger sister, Gretel, their hardworking mother and disabled father. The dad, Raff Brinker, suffered severe head injuries in a workplace injury that wiped out his memory, and now he needs constant watching over. A grand skating race with a generous prize is announced, but will the Brinker kids ever be able to scrape together enough funds to purchase adequate skates? Not to mention, mean boy Carl Van Schummel wants to sabotage their chances of even entering.

We learn some great details about Holland, the country below sea level, but the plot itself crawls along at snail's pace until way down the track. And 15-year-old Hans himself has that, 'What a guy!' quality from the very start, which wipes out the need for character development. Self-sacrificing, noble, industrious and resourceful, he has no hero's journey, as such. In fact, we get the idea that if he wasn't such a exemplary specimen of young manhood, far out of anyone else's league, all the instances of good luck throughout the story wouldn't have fallen together as beautifully as they do.

If this was a travel brochure rather than a novel I would have liked it better. Here is a sample of its good description about the setting itself.

'Often the keels of floating ships are higher than the roofs of the dwellings. The stork clattering to her young on the house peak may feel that her nest is lifted far out of danger, but the croaking frog in neighbouring bulrushes is nearer the stars than she. Water bugs dart backward and forward above the heads of chimney swallows, and willow trees seem drooping with shame because they cannot reach as high as the reeds nearby.'

🌟🌟½

June 21, 2023

'They do it with Mirrors' by Agatha Christie

A man is shot at in a juvenile reform home – but someone else dies…

Miss Marple senses danger when she visits a friend living in a Victorian mansion which doubles as a rehabilitation centre for delinquents. Her fears are confirmed when a youth fires a revolver at the administrator, Lewis Serrocold. Neither is injured. But a mysterious visitor, Mr Gulbrandsen, is less fortunate – shot dead simultaneously in another part of the building.

Pure coincidence? Miss Marple thinks not, and vows to discover the real reason for Mr Gulbrandsen’s visit.

MY THOUGHTS:

Miss Jane Marple is tipped off that something's fishy in the household of Carrie Louise, her old school chum from way back, who has a tendency to marry intense, idealistic men. Carrie Louise's current husband, the single-minded Lewis Serracold, operates Stonygates, a reformatory school for delinquent boys that emphasises nurturing and rehabilitation. A sign posted above the door announces, 'Recover hope, ye who enter here,' the reverse of 'abandon hope' from Dante's Inferno. The guy deserves credit for trying hard.

Miss Marple goes for a long visit, and trouble erupts when the young secretary, Edgar Lawson, tries to kill Serracold in a delusional frenzy. Lawson himself is an ex-reform school boy with a persecution complex and delusions of grandeur. No sooner is potential tragedy soothed than Christian Gulbrandsen, Carrie Louise's step-son from her first marriage, is found dead in his bedroom. He's been shot.

It's revealed that Christian was trying to uncover a plot against Carrie Louise. The culprit is presumably still intent on their first murderous mission. Why anyone would want to hurt gracious and cherished Carrie Louise is baffling, especially when the suspects are narrowed down to a small circle of her nearest and dearest.

There is her grumpy and frumpy widowed daughter, Mildred; two more step-sons from Carrie Louise's second marriage, Alex and Stephen Restarick, who revere her; and her vibrant and beautiful granddaughter, Gina, recently back from America with her disgruntled young husband, Walter, in her wake. He is everyone's main scapegoat since he's new on the scene, yet the police wonder if that should, in fact, rule Walter out. Overlooking everyone is the stern but devoted 'Jolly', Carrie Louise's elderly companion who adores her.

Miss Marple really plays on her slightly doddery and disarming front. She has a warm and sympathetic way of encouraging confidence, which reinforces to her how often people make assumptions about others. Every so often she expresses gratitude for her nephew, Raymond, who supports her financially. It's lucky for the world of crime that he does. She's one of my favourite sleuths.

I love the setting of Stonygate, the shabby, genteel old mansion that's gone to seed. It's a perfect backdrop for all the action. Its dodgy electrical wiring was installed by Dr Gulbrandsen 'when electrical light was a novelty.' Gee whiz, what a landmine, when mavericks could fiddle around with a building's wiring in an era long before safety switches.

Lewis' surprising goal stands out to me too. In his line of work, he believes that transportation saved many a potential criminal. Lewis Serracold believes, 'modern and civilised conditions are too complex for some simple and undeveloped natures,' so being shipped overseas to form new lives in simpler surroundings is the making of many. His big dream is to purchase something like a group of small islands to repeat the experiment with some of his boys. It's a topsy-turvy notion that's hard for an Aussie like me to wrap my head around, having been taught from the cradle that we were merely a harsh dumping ground for our convicts, supposed desperadoes, many of whom were simply destitute and starving.

The illusional nature of the title really impresses me. It's a great read, really hard to put down, clever and satisfying. My only gripe is that toward the end, the incidental death toll rises by a few more, which seem dramatic and unnecessary. It includes some of Carrie Louise's most beloved people, yet she doesn't seem overly distraught. I guess there's no place for genuine grief to be shown in a cosy murder mystery, so we've got to assume it happens off stage. (Perhaps that explains why I find the genre awesome, but rarely 5 star material.)

Whew, I'm glad my two favourite characters have nothing to do with it.

🌟🌟🌟🌟

The Vince Review

I invite you to treat this blog like a book-finder. People often ask the question, "What should I read next?" I've done it myself. I try to read widely, so hopefully you will find something that will strike a chord with you. The impressions that good books make deserve to be shared.

I read contemporary, historical and fantasy genres. You'll find plenty of Christian books, but also some good ones from the wider market. I also read a bit of non-fiction to fill that gap between fiction, when I don't want to get straight on with a new story as the characters of the last are still playing so vividly in my head. ...more

- Paula Vince's profile

- 108 followers