Tarek Fatah's Blog, page 2

October 21, 2017

Burkas and Niqabs pose a Public Safety Risk in Canada as well as the rest of the World

“Around the world, numerous criminals have fled arrest wearing burkas, everywhere from London’s Heathrow airport to the infamous Lal Masjid armed revolt by jihadis in Islamabad. My plea to vote-grabbing Canadian politicians of all political stripes in English-speaking Canada is, for once, be honest. Put the racist card aside and recognize burkas and niqabs pose a serious public safety risk.”

October 25, 2017

Tarek Fatah

The Toronto Sun

The slur of “racism” has been hurled at Muslims who support Quebec’s Bill 62 — the new law banning face coverings, for example, the burka and niqab, when giving or receiving government services.

From Ontario Liberal Premier Kathleen Wynne to Ontario Progressive Conservative Leader Patrick Brown, many white politicians and liberal media commentators have been quick to label any support of Bill 62 racist.

Since I, a Muslim, support Bill 62, I guess that makes me a racist.

Indeed, it’s not uncommon to hear whispers suggesting Muslims like me who support the burka and niqab ban are “sell-outs” within the Muslim community. And that white politicians who oppose Bill 62 are trying to salvage the reputation of our community, despite our supposed betrayal.

After all, what do these politicians have to lose?

The political race to the bottom to curry favour with the so-called “Muslim vote bank” in Canada, as they see it, has worked well for both Conservatives and Liberals.

Charmed as they are by many second-generation radical Muslims who were born in Canada, some of whom hate western civilization more than their parents do.

But none of the attacks on Quebec’s burka/niqab ban was more disingenuous than one told by a well-coiffed hijabi on Canadian television recently, dismissing the public safety aspect of people wearing facemasks.

This young Muslim woman claimed there has not been a single incident where someone wearing a burka committed a crime.

To set the record straight, here are just a few examples of criminal activities committed by men and women wearing burkas and other face coverings in Canada:

Two months ago, on Aug. 17, 2017, an armed robbery took place at a Scotia Bank branch in Milton, Ontario. Police said one of the two suspects was wearing a balaclava.

On Sept. 9, 2015, two burka-wearing male teens charged into a Toronto bank in the Yonge Street and Highway 401 area. Both were later arrested in Ajax.

On Oct. 14, 2014, two men wearing burkas robbed a Toronto jewellery store in the York Mills and Leslie Street area, and walked away with $500,000 worth of gold and precious stones.

On Aug. 18, 2010 an armed robbery by two masked men took place at a Scotiabank branch in Vaughan, north of Toronto.

Ottawa police have in the past cited a handful of robberies in that city involving male suspects using Muslim women’s religious garments as disguises.

Some of us will never forget how a young Toronto Muslim woman, Bano Shahdady, threw off her burka as she was divorcing her husband, only to be stalked by him disguised in a burka. He entered her apartment building and killed her in July, 2011.

It was a story few media were willing to delve into, but because I knew the family, one journalist did report about this burka-related murder that almost went unreported.

Around the world, numerous criminals have fled arrest wearing burkas, everywhere from London’s Heathrow airport to the infamous Lal Masjid armed revolt by jihadis in Islamabad.

My plea to vote-grabbing Canadian politicians of all political stripes in English-speaking Canada is, for once, be honest.

Put the racist card aside and recognize burkas and niqabs pose a serious public safety risk.

October 20, 2017

Malala Yusufzai to CBC: “Why should I cover my face [in a Burka] … It is Taliban Culture”

Canada and the West should Ban the Burka – Toronto Sun column from September 2013

Sept. 17, 2013

While Canada has been embroiled in the controversy surrounding Quebec’s plan to outlaw the hijab as a headdress for its Muslim public employees, across the pond in the UK, it’s the niqab, — a full-face mask worn by some Muslim women — that is creating a storm.

On Monday, a British judge at London’s Blackfriars Crown Court ruled a Muslim woman known only as “D”, who was facing charges of intimidation, would be allowed to attend her own trial wearing a full-face mask.

In a ruling that shocked Britain, Judge Peter Murphy admitted that concealing the face would “drive a coach and horses through the way justice has been administered in England and Wales for centuries.”

Yet he apparently gave in to the religious blackmail employed by Islamists, who fling allegations of racism and Islamophobia at anyone who dares criticize this medieval misogynist practice being introduced throughout the West in the name of Islam.

To satisfy critics of the niqab, the London judge added a meaningless compromise.

He ruled that if the accused took the stand and gave evidence, she would have to remove the face mask and show her face to the jury.

He wrote, “If the defendant gives evidence she must remove the niqab throughout her evidence.” The operative word being “‘if”.

The fact is, people accused of criminal wrongdoing have the right not to testify, thereby avoiding cross-examination by the crown, and many accused avail themselves of this right.

Thus, for all practical purposes, the accused woman in London may never be seen by anyone, whether she is found guilty or innocent.

In reaching his decision, Judge Murphy relied on the recent Supreme Court of Canada decision involving a Muslim woman identified only as “NS”, who, as the complainant in a sexual assault trial, had refused to take off her niqab in court.

At the core of the cases involving both the accused “D” in Britain and complainant “NS” in Canada, is the women’s claim that masking their face is their religious obligation and as such a fundamental right.

Nothing could be further from reality, though no non-Muslim has as yet had the courage to call the bluff of Islamists who employ the niqab (and burka) as a political symbol, a sort of a middle finger to the West.

As the Muslim Canadian Congress said in 2009, “there is no requirement in the Qur’an for Muslim women to cover their faces. Invoking religious freedom to conceal one’s identity and promote a political ideology is disingenuous.”

No less an authority than Egypt’s late Sheikh Mohamed Tantawi, dean of al-Azhar university, stated the niqab was merely a cultural tradition and that it had no connection to Islam or the Qur’an.

If there is any doubt about the religiosity of the niqab and burka, one should take a look at the holiest place for Muslims, the grand mosque in Mecca, the Ka’aba.

For more than 1,400 years, Muslim men and women have prayed in what we believe is the House of God, and for all those centuries, female visitors have been explicitly prohibited from covering their faces.

It’s time to take the veil off the lies Islamists tell and to ban the niqab and burka from all public places.

And finally, to use them as a reference point for students studying the effects of brainwashing.

October 19, 2017

Rosie DiManno of the Toronto Star questions the wearing of the Burqa as ‘Feminism’

Is covering women’s faces feminism?

By Rosie DiManno

Oh, this is rich: a defence of the veil as feminist prerogative. What next — promotion of the chastity belt as post-feminist birth control?

Events thousands of miles away, in England, are resonating here in Canada, in yet another round of politicized and polarizing debate over the alleged “otherness” of pious Muslims, the purported unwillingness of some to accept the secular status quo of the Western societies in which they reside.

In this case, a young teaching assistant’s refusal to remove her niqab — the piece of cloth that some Muslim women wear to cover their faces, hiding everything below the eyes — has triggered anew fierce suspicions of multiculturalism accommodation run amok, demonstrating again how damnably difficult it has become to separate isolated cases from the larger context of political and ideological agendas.

What some frame as a religious obligation or simply esthetic choice has been taken up by others as evidence of bigotry, on one side, and self-imposed segregation on the other, an in-your-face rejection of values held most dear by the dominant culture.

One value: We are our faces.

Individuals — not just part of various collectives as defined by gender or faith, but each of us distinguishable by features that express what’s going on inside.

Identities — the openness of a society that’s revealed in every single countenance, reinforcing the central fact of diversity and pluralism, our shared humanity.

In Western societies, indeed in most Islamic societies, too, we relate to one another at least initially by what we can see: the smile, the frown, what’s crossing our minds crossing our faces, too. The niqab, whatever its other messages may be, says: You can’t see and you must not see.What I have under here is so sacred, so untouchable, that just your glance is contaminating. You are not to be entrusted with the privilege of knowing me even so much as this.

I can think of no more insulating a statement than the veil. That one small rectangle of fabric speaks volumes about separateness and exclusion. It carries both an intrinsic sense of superiority (my faith, which sets me apart) and inferiority (my gender, which renders me de facto prey, thus requiring this protection, which just happens to be the invention of males).

Humbleness versus arrogance.

From this hard knot of contradictions has unravelled a further thread, a substrata string, and the most preposterous rationalization of all, particularly coming out of the mouths of men — that the niqab is a feminist declaration. This is so duplicitous a construct as to be almost comical, if it weren’t being seriously posed in some quarters, and helpfully parroted by a small number of women who apparently have no confidence in either their own character or the ability of the opposite sex to control their beastly tendencies.

Really, we can be our own worst enemies sometimes. And, more unforgivably, the enemy of other women.

There are, perhaps, legitimate reasons for asserting a woman’s right not to show anything other than her eyes to the world, and barely that. In a free country, one would like to believe that women — including Muslim women, in conservative communities — are making independent choices, based on their own needs and wishes and comfort zone.

But let’s not be disingenuous here. There is ample evidence, overwhelming evidence, of religious and cultural pressures, those steeped in a firmly patriarchal code of conduct, for the marginalizing of adult females, practices that are fundamentally at odds with basic concepts of gender equality.

Ontario came alarmingly close to permitting the application of sharia law in family arbitration matters — when multicultural sensitivities almost trumped women’s rights — before Premier Dalton McGuinty stepped in and said “no,” that’s just not acceptable, however cloaked in the disguise of ethnic and ethic reasoning.Sharia law works, is made to work, by coercive imposition in Islamist countries where women are chattels, and largely illegitimate governments rely on the support of religious authorities for even the slimmest of mutually satisfying endorsement.

In some Islamic jurisdictions — just as an example — rape cases can only pass the trial test if four people come forward as witnesses to the crime. How often do you think that occurs?

What was most disheartening to many of us about the barely averted sharia threat here is that the proposal had been studied and advanced by a woman, no less than the province’s previous attorney general, in an NDP government.This provided threadbare cover, deeply dishonest on its merits, for an alliance of reactionaries and fundamentalists (whether born-again or always-were) to justify treating Muslim women as lesser beings. Sharia law would have exposed a palpably vulnerable constituency to the paternalistic mercies of religious tribunals.

I do not trust the sophistry inherent in a pedantically twisted intellectualization of the veil, as if it were something other than what it demonstrably is: segregation of women by other means.

We have long progressed beyond the point where the Bible could be used to justify misogyny.No sane person would quote from Scripture — or be permitted to do so, in a mass-market general newspaper — those anachronistic texts that sanction unequal treatment of women up to and including the beating of a disobedient spouse or child. Bible-thumping is repellent, whether applied to women or children or homosexuals or any other group whose behaviour is construed as sinful.

Qu’ran-thumping should be no less unsavoury.

So spare me what that holy book has to say about veiling women, especially when even Islamic scholars are divided on it. Like Britain, ours is a secular society trying to cope with conflicting demands; we protect the rights of people to be religious, as they see fit, and not religious, as they see fit. What we’ve not done a very good job of is protecting the dignity, sometimes the very lives, of wives and daughters and sisters who are very much under the thumb of fathers, husbands and brothers, viewed as property, a reflection on their own paramount authority in the household.

It is not patronizing to acknowledge that many Muslim women who wear the niqab — and they are themselves in a small minority — do so not out of personal choice but because they are bullied, tacitly or overtly, into doing so. They must hide their faces so that their men don’t lose face.

And I care a great deal more about their predicament than I do their Islamist sisters who choose to veil under the rubric of feminism.

October 18, 2017

Muslim Women wrapped in Burkas being beaten by an Islamic cleric

Just another day in the life of some women in the Arab World. Don’t ask me what is being said. Take it to an Inter-Faith industry expert and ask him or her to shower their insight on this brutality. Start with the United Church and then perhaps the scholar working with the ‘Outreach’ wing of the RCMP. And if they cannot decipher this video, you can always turn to Senator Grant Mitchell and he is sure to help you understand what these ‘beautiful’ Muslims are up to.

http://tarekfatah.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Man-beating-up-women-to-exorcise-the-devil.mp4

Burka-bandit fails to Rob a Bank in California

Bank robber calls Burka the perfect disguise

NATIONAL CITY, Calif. – Elysia Roiz told 10News she was desperate for money to support her 2-year-old special needs son when she decided to wear a burqa to rob the Wells Fargo on Highland Avenue.

It did not work. After she passed a demand note to the teller, the teller pushed a panic button and Roiz escaped without a dime. She was arrested two months later in Tijuana.

Roiz admitted it was not fair to dress in religious garb to commit a crime.

“I know in other countries they’ve outlawed it, because of people, mostly men hiding firearms inside burqas, and I don’t think it was fair of me to exploit that, but what better costume, you know what I mean?” Rois asked, adding that the garment should be outlawed. “I don’t want to be disrespectful, but I mean, that stuff is so oppressive, like I mean, we fought a lot in the 70s, women did, so that kind of stuff didn’t happen, doesn’t happen.”

She added, “There’s other ways to express religion.”

Hanif Mohebi, the executive director of CAIR, told 10News, “It is obviously ignorance. No one has or should use any symbols or clothing of religious in order to commit any crimes.”

He added that Roiz’s actions could lead to discrimination against other mothers.

“So essentially, this is a double crime,” Mohebi said.

October 17, 2017

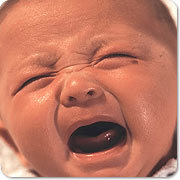

Baby bursts into tears on seeing a woman in Burka | 2006 article about a Muslim woman’s burka test-drive

Friends,

Friends,

British Muslim journalist Zaiba Malik had never worn the niqab. But with everyone from Jack Straw to Tessa Jowell weighing in with their views on the veil, she decided to put one on for the day. She was shocked by how it made her feel — and how strongly strangers reacted to it.

Here is her story. She recounts being at a mosque and finding out that she was the only one in the facemask,

“At the mosque, hundreds of women sit on the floor surrounded by samosas, onion bhajis, dates, and Black Forest gateaux, about to break their fast. I look up and down every line of worshippers. I can’t believe it — I am the only person wearing the niqab. I ask a Scottish convert next to me why this is. “It is seen as something quite extreme. There is no real reason why you should wear it. Allah gave us faces and we should not hide our faces. We should celebrate our beauty.”

Zaiba Malik then writes about her encounter with a baby:

“At the supermarket, a baby no more than two years old takes one look at me and bursts into tears. I move towards him. “It’s OK,” I murmur. “I’m not a monster. I’m a real person.” I show him the only part of me that is visible — my hands — but it’s too late. His mother has whisked him away. I don’t blame her. Every time I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirrored refrigerators, I scare myself.”

Read and reflect.

Tarek

———————-

October 25, 2006

“Even other Muslims turn and look at me”

By Zaiba Malik

The Hindu, New Delhi

[Orignally printed in The Guardian, UK]

“I DON’T wear the niqab because I don’t think it’s necessary,” says the woman behind the counter in the Islamic dress shop in east London. “We do sell quite a few of them, though.” She shows me how to wear the full veil. I would have thought that one size fits all but it turns out I’m a size 54. I pay my £39 and leave with three pieces of black cloth folded inside a bag.

The next morning I put these three pieces on as I’ve been shown. First the black robe, or jilbab, which zips up at the front. Then the long rectangular hijab that wraps around my head and is secured with safety pins. Finally the niqab, which is a square of synthetic material with adjustable straps, a slit of about five inches for my eyes and a tiny heart-shaped bit of netting, which I assume is to let some air in.

I look at myself in my full-length mirror. I’m horrified. I have disappeared and somebody I don’t recognise is looking back at me. I cannot tell how old she is, how much she weighs, whether she has a kind or a sad face, whether she has long or short hair, whether she has any distinctive facial features at all. I’ve seen this person in black on the television and in newspapers, in the mountains of Afghanistan and the cities of Saudi Arabia, but she doesn’t look right here, in my bedroom in a terraced house in west London. I do what little I can to personalise my appearance. I put on my oversized man’s watch and make sure the bottoms of my jeans are visible. I’m so taken aback by how dissociated I feel from my own reflection that it takes me over an hour to pluck up the courage to leave the house.

I’ve never worn the niqab, the hijab or the jilbab before. Growing up in a Muslim household in Bradford in the 1970s and 1980s, my Islamic dress code consisted of a school uniform worn with trousers underneath. At home I wore the salwar kameez, the long tunic and baggy trousers, and a scarf around my shoulders. My parents only instructed me to cover my hair when I was in the presence of the imam, reading the Koran, or during the call to prayer. Today I see Muslim girls 10, 20 years younger than me shrouding themselves in fabric. They talk about identity, self-assurance, and faith. Am I missing out on something?

On the street it takes just seconds for me to discover that there are different categories of stare. Elderly people stop dead in their tracks and glare; women tend to wait until you have passed and then turn round when they think you can’t see; men just look out of the corners of their eyes. And young children — well, they just stare, point, and laugh.

I have coffee with a friend on the high street. She greets my new appearance with laughter and then with honesty. “Even though I can’t see your face, I can tell you’re nervous. I can hear it in your voice and you keep tugging at the veil.”

“Buried in black snow”

The reality is, I’m finding it hard to breathe. There is no real inlet for air and I can feel the heat of every breath I exhale, so my face just gets hotter and hotter. The slit for my eyes keeps slipping down to my nose, so I can barely see a thing. Throughout the day I trip up more times than I care to remember. As for peripheral vision, it’s as if I’m stuck in a car buried in black snow. I can’t fathom a way to drink my cappuccino and when I become aware that everybody in the coffee shop is wondering the same thing, I give up and just gaze at it.

At the supermarket, a baby no more than two years old takes one look at me and bursts into tears. I move towards him. “It’s OK,” I murmur. “I’m not a monster. I’m a real person.” I show him the only part of me that is visible — my hands — but it’s too late. His mother has whisked him away. I don’t blame her. Every time I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirrored refrigerators, I scare myself.

For a ridiculous few moments I stand there practising a happy and approachable look using just my eyes. But I’m stuck looking aloof and inhospitable, and am not surprised that my day lacks the civilities I normally receive, the hellos, thank-yous and goodbyes.

After a few hours I get used to the gawping and the sniggering, am unsurprised when passengers on a bus prefer to stand up rather than sit next to me. What does surprise me is what happens when I get off the bus. I’ve arranged to meet a friend at the National Portrait Gallery. In the 15-minute walk from the bus stop to the gallery, two things happen. A man in his 30s, who I think might be Dutch, stops in front of me and asks: “Can I see your face?”

“Why do you want to see my face?”

“Because I want to see if you are pretty. Are you pretty?”

Before I can reply, he walks away and shouts: “You tease!”

Then I hear the loud and impatient beeping of a horn. A middle-aged man is leering at me from behind the wheel of a white van. “Watch where you’re going, you stupid Paki!” he screams. This time I’m a bit faster.

“How do you know I’m Pakistani?” I shout. He responds by driving so close that when he yells, “Terrorist!” I can feel his breath on my veil.

Things don’t get much better at the National Portrait Gallery. I suppose I was half expecting the cultured crowd to be too polite to stare. But I might as well be one of the exhibits. As I float from room to room, like some apparition, I ask myself if wearing orthodox garments forces me to adopt more orthodox views. I look at paintings of Queen Anne and Mary II. They are in extravagant ermines and taffetas and their ample bosoms are on display. I look at David Hockney’s famous painting of Celia Birtwell, who is modestly dressed from head to toe. And all I can think is that if all women wore the niqab how sad and strange this place would be. I cannot even bear to look at my own shadow. Vain as it may sound, I miss seeing my own face, my own shape. I miss myself. Yet at the same time I feel completely naked.

The women I have met who have taken to wearing the niqab tell me that it gives them confidence. I find that it saps mine. Nobody has forced me to wear it but I feel like I have oppressed and isolated myself.

Maybe I will feel more comfortable among women who dress in a similar fashion, so over 24 hours I visit various parts of London with a large number of Muslims — Edgware Road (known to some Londoners as “Arab Street”), Whitechapel Road (predominantly Bangladeshi) and Southall (Pakistani and Indian). Not one woman is wearing the niqab. I see many with their hair covered, but I can see their faces. Even in these areas I feel a minority within a minority. Even in these areas other Muslims turn and look at me. I head to the Central Mosque in Regent’s Park. After three failed attempts to hail a black cab, I decide to walk.

A middle-aged American tourist stops me. “Do you mind if I take a photograph of you?” I think for a second. I suppose in strict terms I should say no but she is about the first person who has smiled at me all day, so I oblige. She fires questions at me. “Could I try it on?” No. “Is it uncomfortable?” Yes. “Do you sleep in it?” No. Then she says: “Oh, you must be very, very religious.” I’m not sure how to respond to that, so I just walk away.

At the mosque, hundreds of women sit on the floor surrounded by samosas, onion bhajis, dates, and Black Forest gateaux, about to break their fast. I look up and down every line of worshippers. I can’t believe it — I am the only person wearing the niqab. I ask a Scottish convert next to me why this is.

“It is seen as something quite extreme. There is no real reason why you should wear it. Allah gave us faces and we should not hide our faces. We should celebrate our beauty.”

I’m reassured. I think deep down my anxiety about having to wear the niqab, even for a day, was based on guilt — that I am not a true Muslim unless I cover myself from head to toe. But the Koran says: “Allah has given you clothes to cover your shameful parts, and garments pleasing to the eye: but the finest of all these is the robe of piety.”

Endurance test

I don’t understand the need to wear something as severe as the niqab, but I respect those who bear this endurance test — the staring, the swearing, the discomfort, the loss of identity. I wear my robes to meet a friend in Notting Hill for dinner that night. “It’s not you really, is it?” she asks.

No, it’s not. I prefer not to wear my religion on my sleeve … or on my face. —

© Guardian Newspapers Limited 2006

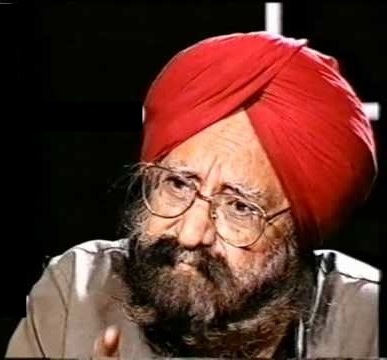

Burka “is [the] single most reprehensible cause for keeping Muslims backward … sooner it’s abolished, the better” – Khushwant Singh

“In my view, shared by all my Muslim friends, burqa is the single most reprehensible cause for keeping Muslims backward (it is synonymous to jehalat — ignorance and backwardness). The sooner it is abolished, the better.”

Khushwant Singh

Hindustan Times

At the recent Book Fair in Delhi there was a stall selling Islamic literature. Friends who went round the stalls told me that among the hottest sellers was Answer to Non-Muslim Common Questions About Islam by Dr Zakir Naik (Madhur Sandesh Sangam).

The learned doctor, who has a phenomenal memory when it comes to quoting chapters, verses and lines of the scriptures, has chosen 20 questions, most often asked by non-believers: they include polygamy, burqa, drinking, eating pigmeat, afterlife, and kafirs.

I have heard Zakir Naik hold forth on these and other subjects several times on television before large receptive audiences, who hear him spellbound. I disagree with almost everything he has to say about misconceptions about Islam. Though by definition (a kafir), I don’t believe in God, satan, angels, devils, heaven or hell, I feel hurt and angry because I am emotionally and rationally bothered by the sorry plight of Muslims today.

I find Naik’s pronouncements somewhat juvenile. They seldom rise above the level of undergraduate college debates, where contestants vie with each other to score brownie points.

I will deal with only four of the twenty topics he deals with — two of minor and two of major importance.

Muslims and Pork

Why is eating pigmeat forbidden in Islam? Dr Naik tells us that the “pig is one of the filthiest animals on earth.”

Agreed, it eats garbage, including human and animal excreta. He further adds, “The pig is the most shameless animal on the face of the earth. It is the only animal that invites its friends to have sex with its mate” I admit I was not aware of this swinish aberration. He goes on to list 70 different types of diseases caused by eating pigmeat. He does not tell us why the vast majority of non-Muslims, non-vegetarians of the world relish pigmeat in different forms: ham, bacon, pork, sausages, salami etc.

Many Pacific island economies depend on breeding pigs. I for one have not heard of great epidemics caused by consumption of pig meat.

Muslims and Alcohol

Why is alcohol forbidden to Muslims? Actually, what is forbidden by the Quran is drunkenness, not drinking. However, Dr Naik construes it to be a sin.

He says, “Alcohol has been the scourge of human society, since time immemorial. It costs enormous human lives and terrible misery to millions throughout the world.”

He lists 19 diseases, including eczema, caused by intake of liquor. One does not have to quote the scriptures to prove that excessive drinking ruins one’s health, impoverishes families, leads to bad behaviour and crime. It is plain common sense.

People all over the world overdo it and suffer. Those who drink within limits enjoy it. I have been drinking for 70 years. I have not been drunk even once in my life, never fallen ill nor offended anyone.

I am 94 and still drink everyday. My role model is Asadullah Khan Ghalib. He drank every evening and alone. I look forward to my sundowners. For me and for millions of others, drinking has nothing to do with religion.

Let us see what Dr Naik has to say about two more serious subjects: polygamy and hijab (veil).

Muslims and Polygamy

“The Quran is the only religious book on the face of this earth that contains the phrase “marry only one,” he asserts. And explains the verse on the subject “marry women of your choice, two, three or four; but only fear that ye shall not be able to do justice (with them), then only one”.

And since “ye are never able to be fair and just as between women. Therefore, the verdict is in favour of one wife at a time. “Hindus are more polygamous than Muslims,” writes Dr Naik.

There are more women than men in the world; so what are women who can’t find unmarried men do except become co-wives of married men? Or become “public property?” So goes the learned doctor’s argument.

He does not deign to deal with the situation as it exists today. Every other religion other than Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism now forbids men from having more than one wife at a time.

Muslims are the sole exception though only a miniscule minority, mainly Arabs, have multiple wives.

Apply for a visa to some country like Indonesia and Malaysia and you will have to fill a column naming up to four wives accompanying you. The answer to the problem of women out-numbering men is not polygamy, it is freedom to engage in extra-marital relation or have them staying single. It is better than having a harem.

Muslims and Burka

Dr Naik is in favour of women wearing burqas from head to foot, girls not going to mixed schools or colleges, nor going into professional institutions in which they have to expose their faces etc. This amounts to denying them, equal rights with men.

In my view, shared by all my Muslim friends, burqa is the single most reprehensible cause for keeping Muslims backward (it is synonymous to jehalat — ignorance and backwardness). The sooner it is abolished, the better.

He castigates the western society in no uncertain terms: “Western talk of women’s liberalisation is nothing but a disguised form of exploitation of her body, degradation of her soul and deprivation of her honour.

“Western society claims to have uplifted women. On the contrary, it has actually degraded them to the status of concubines, mistresses, and society butterflies who are mere tools in the hands of pleasure seekers and sex marketers….”

All I can say in reply is “Dr. Naik, you know next to nothing about the Western society and are talking through your skull cap. People like you are making the Muslims lag behind other communities.”

October 16, 2017

“Why should the State tolerate the Burka,” asks Yasmin Alibhai-Brown

Veiled Threats

By Yasmin Alibhai-Brown

The Evening Standard

Last week when I was browsing in shops on Chiswick High Road, I became aware of awoman shadowing me, rather too close in that private space we all subconsciously carry around us.

She was covered from head to toe in a black burkha Tight, white gloves covered her hands and her heels clicked. She wore perfume or hair oil smelling of roses . At one point, I nearly tripped over her foot and she said ‘sorry’ softly.

I drove home and twenty minutes later the doorbell rang. I opened the door to see thewoman standing there, her raven cloak billowing as gusts of wind blew up from the park opposite. Her eyes were light brown. She said nothing at first, then asked in perfect English if she could come in. I felt panic rising. Because I write on controversial issues at this fraught time, death threats come my way and I have been advised by the police to be extremely careful about loitering strangers.

‘Please, please, l know who you are and I must speak to you, I saw you in the shops, and followed you in my friend’s car. I must show you something’ . ‘Who are you?’ I asked, even more scared now. She pleaded some more, told me her name, showed me her EU passport.

She was from somewhere near Bolton she said. I let her in. She took off her burkha to reveal a sight I shall never forget.

There, before me was a woman so badly battered and beaten, that she looked painted in deep blue, purple and livid pink. The sides of her mouth were torn- ‘he put his fist in my mouth because I was screaming’, she explained.

‘Who did?, who did this to you?’ ‘My father and two brothers and then they forced me to wear the niqab (burka) , so no-one can see what they’ve done.

Many families do this, to keep their black secrets. They beat up the women and girls because they want them to agree to marriages or just because the girls want a little more independence, to go to college and that. Then they make them wear the burkha to keep this violence a secret. They know the police are now getting wise to honour killings and so they have this sheet to hide the proof’.

Over the afternoon she sobbed and told me about the horrors of her own life and her dead friend, killed, she claims by family members who felt she had shamed them:’ But she had done nothing at all. Someone told the family they saw their daughter talking to a couple of guys at the bus stop and that she was holding the hand of one of them. It was a lie.

But this gossip can kill us’. In her own case she says at first her father and brothers wanted to know if she too was as ‘bad’ as her friend. So they beat her to get her to confess to things she hadn’t done. Then they tried to get her to quit her teacher training course and when she refused, they locked her in a bedroom and carried on abusing her, the youngest brother in particular who was, she said, maddened with suspicion.

A few days ago she escaped, with her passport and a friend drove her to London. I have a contact who runs an safe refuge in the north west of the city. We trust each other. I got ‘S’ a place there and gave her some money, enough to live on for a few weeks.

She has my number and I hope she calls if she needs to. As I dropped her off she said she was feeling guilty that the escape would break her mother’s heart. Her mother’s heart, I said, should have broken to witness what was done to her daughter. ( including what I did next to help I THINK YOU NEED TO GIVE AN IDEA: IECALLED A RFEUGE) Some of what she told me has to be kept confidential for her safety and mine.

‘S’ was twenty five, from a chemistry graduate, and a battered woman imprisoned in black polyester.

This incident set me thinking again about the burka and whether we, as a liberal country, should accept it. There has been a marked increase in the use of burkhas in Britain. This is the next frontier for puritanical Muslims who believe females are dangerous seductresses, liable to drive men mad with desire.

Women and girls as young as twelve, they say, must cover up to avoid suchprovocation. ( Don’t Muslim men mind that they are portrayed as wildly lusty? And if they are, why don’t they wear blindfolds or avert their gazes?)

The pernicious ideology is propagated by misguided Muslim women who claim the burkha is an equalizer and liberator. In a film I made for Channel4 I met an entire class of teenagers at a Muslim secondary school in Leicester who told me negating their physical selves in public made them feel great.

I confess I respond to this garment with aversion. I find the hijab and the jilbab ( long cloak) problematic too because they again make women responsible for the sexual responses of men and they define femininity as a threat. But the burkha is much, much worse as it totally dehumanizes half the human species. Why do women defendthis retreat into shrouds?

When I try to speak to some of them on the street they stare back silently. In a kebab café in Southall last week, a woman in burkha sat there passively while her family ate – she couldn’t put food into her own mouth.

One mother told her young daughter in Urdu to walk away from me, a ‘kaffir’ in her eyes.

Domestic violence is an evil found in all countries, classes and communities. Millions of female sufferers hide the abuse with concealing clothes and fabricated stories. But this total covering makes it absolutely impossible to detect which is why S and other victims of family brutality are forced to wear it.

I now have twelve letters from young British Muslim women making these allegations, all too terrified to go public. Several say that in some areas where hard line imams hold sway the hijab is seen as inviting because it focuses attention on the face. If the women refused to comply they were beaten.

Heena, Iman write that their husbands insist on the covering because it is easier to conceal the brutality within the marriage. Mariyam writes:’ He says he doesn’t want his name spoilt- that his honour is important. If they see what he is doing to me, his name will be spoilt’. Not all woman in burkha are the walking wounded, but some are and the tragedy is that it is impossible to pick up the signs.

The usual network of concerned people- neighbours, colleagues, pupils, teachers, police or social workers would need to be approached by the traumatised women and girls- as I was by ‘S’. There are other risks too.

A body denied any contact with the sun must lack vital vitamins. Some London University colleges have decided to disallow the garment for security reasons. (What will happen when ID cards come in? And how do examiners recognise candidates?)

Should the nation support all demands in the name of cultural or religious rights? In several schools already Muslim parents are refusing to let their girls swim, act or take part in PE, interference I personally find appalling. This is a society which prizes individual autonomy and the principle of absolute gender parity.

The burkha offends both these principles and yet no politician or leader has dared to say so. Even more baffling is the meek acceptance of the burkha by British feminists who must be eepelled by the garment and its meanings.

What are they afraid of? Afghani and Iranian women fight daily against the shroud and there is nothing ‘colonial’ about raising ethical objections to this obvious symbol of oppression.

The banning of the headscarf in France was, in fact, supported by many Muslims. The state was too arrogant and confrontational but the policy was right. A secular public space gives all citizens civil rights and fundamental equalities and Muslim girls have not abandoned schools in droves as a result of the ban.

Shabina Begum should have been the moment to confront the challenge. This spring Shabina Begum took her school to Appeal Court for refusing to let her ‘progress’ from the hijab to the jilbab, a full body cloak. She won the right. For many of us modernist Muslims this was a body blow and today we fear the next push is well underway for British Muslim woman to wear the body cage of Afghani women under Taliban.

Interviewed by the journalist Andrew Anthony, Rahmanara Chowdhury, a teacher of interpersonal and communications skills in Loughborough defended her burkha by saying she felt more empowered being just a voice. A teacher, can you believe it? Well soon some Imam will pronounce that the voice or scent of a woman are too seductive to be allowed in public spaces. Then what?

Who said a mother had to hide her face from her babies in the park?

Not the holy Koran for sure. Its injunctions simply call for women to guard their private parts, to act with modesty. Scholars disagree about the wrap and even the hijab. More than half the world’s Muslim women do not cover their hair except when in mosque.

There are some who do choose the garment without coercion, the nun’s option you might say. I judge this differently. My experience of S and other women who have written to me in despiar is that many are being forced or brainwashed into thinking their invisibility is what God wants. That is not a choice. The British state is based on liberal values- individuals can decide what they want to do as long as it doesn’t cause harm to others. Sometimes that right is taken even if there is harm caused to others- smoking and excessive drinking for example.

But within this broad liberalism, there are still restrictions and denials for the sake of a greater good. Nudists cannot walk our streets with impunity, and no religious cult can demand the legal right to multiple marriages.

Why should the state then tolerate the burkha, which even in its own terms turns women into sexual objects to be packed away out of sight?

WHAT ABOUT SHORTER HEAD COVERINGS? MID LENGTH VEILS ETC _ YOU NEED TO SAY WHERE YOU STAND ON THOSE

There is much anxious tip-toeing around the issue but it affects us all. Thousands of liberal Muslims would dearly likethe state to take a stand on their behalf. If it doesn’t, it will betray vulnerable British citizens and the nations most cherished principles, including liberalism.

Worst of all it will encourage Islam to move back even faster into the dark ages instead of reforming itself to meet the future.

October 14, 2017

Prof. Mohammad Qadeer: Concealment of the face under a Burka is neither religiously necessary nor socially desirable

Masking the truth

By Prof. Mohammad Qadeer

Queen’s University, Kingston

Globe and Mail, Toronto

If you live in New York, London, Toronto or other cities of Europe and North America, you may have seen an occasional woman with the niqab, the face veil that conceals most of the face except the eyes.

The face veil has been appearing in the public space of Western cities since the 1990s, coinciding with the rising consciousness of Islamic identity.

Amidst throngs of women in body-revealing clothing, seeing a woman with her face concealed and her eyes peeping out of the wraparound veil is surprising. Though I grew up in a Muslim country, the first time I saw a woman clad in the niqab was in Montreal in 1997. It was an odd sight for me. I could not help doing a double take, asking myself “here of all places?”

I have known the burka, a head-to-feet coverall made notorious by the Taliban. It covers the eyes, too, with a thin see-through material. My mother at one time wore a burka, though she discarded it when her daughter refused to don one, and as the custom was fast disappearing from urban Pakistan. I knew the niqab from the fable of the Arabian Nights.

Understandably, seeing it on a live person in downtown Montreal was odd, if not shocking, particularly after decades of living in North America.

The niqab is beginning to cause some public concerns in Europe. The city of Maaseik, Belgium, has banned it from public places. Other towns in Belgium and Holland are contemplating similar actions. There are some questions of common interest that arise from the spread of this custom in Western societies.

The niqab should be differentiated from the hijab, which is just a scarf tied around the head, leaving the face completely visible. The hijab has religious and cultural antecedents in Europe. It is like the traditional head scarf of women in Italy, Greece or Russia.

The niqab is another matter. It is a statement of women’s self-concealment. Those who wear it consider it to be their religious obligation.

The argument about concealing one’s face as a religious obligation, is contentious and is not backed by the evidence. Muslim women all over the world overwhelmingly do not wear either the niqab or the burka.

There was never a time in Muslim history, not even in the early days of Islam, when a majority of women covered their faces. It was only the practice of some tribes, small orthodox sects and women of the ruling elite. Recent evidence from impromptu TV shots of the tsunami devastations in Indonesia, earthquake victims in Pakistan, street crowds in Palestine, Iraq or Egypt, seldom show any women wearing the niqab.

Rural women and women workers in cities have always gone about with their faces visible. The niqab has been the luxury of some puritanical and leisured families. Yes, in conservative and tribal cultures of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia or parts of the Gulf, women conceal their faces. Yet even in these countries, a slight reduction of social pressures brings out large numbers of women without face veils.

Even doctrinal Islam has no unanimity about a woman covering her face.

For centuries, arguments have raged about the body covering that is obligatory for women’s modesty in Islamic society. Those advocating a woman concealing her face are a small and orthodox minority of Islamic scholars and jurists.

In Western societies, the niqab is also an assertion of Muslim identity in an environment of felt discrimination. Yet this choice has social implications especially for those living in pluralist societies. From driving or cashing a cheque to boarding a plane, there is a host of activities requiring photo identity, for example. The niqab has led to an awkward confrontation in such situations.

In Western societies, the niqab also is a symbol of distrust for fellow citizens and a statement of self-segregation. The wearer of a face veil is conveying: “I am violated if you look at me.” It is a barrier in civic discourse. It also subverts public trust.

Yet the primary victims of the niqab are its wearers. A prospective employer may be justified in not hiring someone whose facial expressions are unavailable to those communicating with her, be they customers, co-workers or the general public.

Similarly, the educational experience of a woman clad in the niqab is compromised because of her visual segregation from fellow students, teachers and team members. The niqab necessitates awkward and costly accommodations for its wearers in offices and schools. It has social and personal costs.

In pluralist and democratic societies, women have won equality after a long struggle. The niqab is a symbol of self-inflicted inequality and exclusion. Someone may argue that it is a right of an individual to wear what she likes. Yet all rights have limits. Your right to conceal your face infringes others’ right to know who you are.

Muslim women living in the West can practise modesty with the hijab or in other suitable ways that allow the face to be visible. Concealment of the face is neither religiously necessary nor socially desirable. Muslim communities should reappraise this custom, before a scare about terrorists or a bank hold up raises a public uproar against the niqab.

Tarek Fatah's Blog

- Tarek Fatah's profile

- 79 followers