Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 8

October 9, 2012

Amazeballs

[image error]The Manga UK podcast is back for its eighth episode, in which Jerome Mazandarani offers sage advice on dealing with school bullies, Andrew Partridge of Scotland Loves Anime plugs his film festival in Edinburgh and Glasgow, Jeremy Graves on what’s coming up at the MCM Expo, and Jonathan Clements on the dangers of sharing a bed with a third-degree blackbelt. And when Jerome is suddenly caught short, Andrew Hewson steps in to the breach.

0:00:00 – 0:04:55 : Pre-Show chatter.

0:04:55 – 0:24:03 : New releases, production snafus, the certification of Madoka Magica, and how new releases ‘sound’, Ninja Scroll and why pre-ordering is a good idea.

0:24:03 – 00:38:35 Manga UK & Kaze UK plans for London MCM Expo, free hugs at conventions,

00:38:35 – 00:49:28 A preview of Scotland Loves Anime in Glasgow and Edinburgh. Also, reasons why “amazeballs” really is a word.

00:49:38 – 1:28:19 [END] Ask Manga UK, featuring questions on older series, licensing titles, best sellers and more! Favourite manga, including Domu and Shooting Stars in the Twilight. The history of Dark Horse Comics in the UK, and their strange transformation. Details of Toshio Maeda at the Expo, and how not to ask him for a “controversial” image. The problems caused by middlemen in acquiring anime rights. Sales figures for Manga Entertainment’s top sellers, including Akira, Naruto and a couple of surprises.

Available to download now, or find it and an archive of previous shows at our iTunes page. For a detailed contents listing of previous podcasts, check out our Podcasts page.

October 3, 2012

Taking the High Road…

Scottish listings mag The Skinny has a mini-interview with me about next week’s Scotland Loves Anime film festival. Who will win the Golden Partridge? What mentalism will unfold among the short films? How many Japanese guests can they fit into a single film festival?

September 24, 2012

Galaxy Quest

My quest to get the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction’s China entries ship-shape continues, with the addition of the latest Galaxy Awards, announced this month, including big wins for Wang Jinkang and Chen Qiufan. Wang gets 10,000 yuan (about £1,000) prize money, which makes a big difference in a country where authors get paid, can you believe it, even worse money than they do in Britain. If Chinese SF is your thing, I also draw your attention to the new, utterly massive entry on Ye Yonglie, which helps tie a lot of the new Chinese material together.

My quest to get the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction’s China entries ship-shape continues, with the addition of the latest Galaxy Awards, announced this month, including big wins for Wang Jinkang and Chen Qiufan. Wang gets 10,000 yuan (about £1,000) prize money, which makes a big difference in a country where authors get paid, can you believe it, even worse money than they do in Britain. If Chinese SF is your thing, I also draw your attention to the new, utterly massive entry on Ye Yonglie, which helps tie a lot of the new Chinese material together.

September 17, 2012

Golgo 13: Clementary

So, apparently the new US release of Golgo 13 includes the commentary track that I recorded for Manga Entertainment in 2007. Very glad to see it getting another airing, particularly since two of my commentary tracks were once dropped from a US release because a timid distributor thought Americans wouldn’t get my sense of humour.

So, apparently the new US release of Golgo 13 includes the commentary track that I recorded for Manga Entertainment in 2007. Very glad to see it getting another airing, particularly since two of my commentary tracks were once dropped from a US release because a timid distributor thought Americans wouldn’t get my sense of humour.

More details on my other commentary tracks can be found here.

September 10, 2012

Podcast #7

The Manga UK podcast is back for its seventh episode, in which Jerome Mazandarani wins friends and influences people in Norwich, Rory Doona discusses the world of Know Your Anime, Andrew Hewson sobs in the corner and Jonathan Clements reveals the inner workings of the Happiness Project. Meanwhile, Jeremy Graves can’t get enough Princess Jellyfist.

The Manga UK podcast is back for its seventh episode, in which Jerome Mazandarani wins friends and influences people in Norwich, Rory Doona discusses the world of Know Your Anime, Andrew Hewson sobs in the corner and Jonathan Clements reveals the inner workings of the Happiness Project. Meanwhile, Jeremy Graves can’t get enough Princess Jellyfist.

Start – 00:03:26 Pre-show chatter including the Contemporary Japanese Media symposium in Norwich.

00:03:26 – 00:15:04 Cliffhanger question answered — what’s changed about anime and fans in the UK? Includes a gratuitous plug for the new translation of the Art of War.

00:15:04 – 00:44:56 Gangnam style, Manga UK news + September releases, Rory speaks, although not for long.

00:44:56 – 1:04:20 Pay-per-view for Initial D, Anime & the Oscars, the zen question regarding the difference between coming third and coming fourth.

1:04:20 – 1:54:15 [End] Ask Manga UK, including details of the Bandai Europe piranha tank and jibes directed at people called Tony and companies called Sony.

Available to download now, or find it and an archive of previous shows at our iTunes page.

September 3, 2012

Alone with Goldorak

[image error]Liliane Lurçat’s A cinq ans, seul avec Goldorak: Le jeune enfant et la télévision (1981) may have been the first book written about anime outside Japan, although it is really about viewers’ responses to something that happens to be anime. It remains a meticulously constructed work of psychological research, by a scientist testing children’s reactions to popular television programmes. She presents an often chilling view of the effects that such a show, made for older Japanese boys several years earlier, might have had on terrified French children, left ‘at [four] years old, alone with Goldorak.’

We might consider the degree to which viewers respond to what they think is on the screen – a possible issue of both ignorance and aesthetics, not in a historical sense, but a perceptual one. When Lurçat (1981: 25-6) asks her child interviewees if the ‘giant robot’ Goldorak really exists, she receives a dizzying array of responses. Lurçat herself notes (1981: 25) that the question is ambiguous – there is, after all, such a thing as Goldorak on television, and even toys that bear its name. It has both a ‘materiality’ and ‘an existence within the animated spectacle’. The children’s replies cannot even agree on the material of Goldorak’s construction, claiming that it is made of stone, or of wood, or is ‘a robot’. Tellingly, one boy calls Goldorak a ‘marionette’ and eight of Lurçat’s respondents claim that Goldorak is ‘a man in disguise’ – either a reference to the pilot of the machine within the show, or perhaps even an indicator that the respondents were not all that sure which show they were supposed to be discussing.

At the risk of injecting a note of snide hypercriticality into the debate, not one of Lurçat’s four-year-old interviewees points out to their adult questioner that Goldorak was not actually a ‘robot’ at all, but in fact a ‘mecha‘ or pilotable machine. Acuff and Reiher (1997: 69), suggest that children under seven are not mentally equipped to understand that Goldorak is a machine operated by human agency, but that is part of Lurçat’s point – that whatever fine distinctions or equivocations an older viewer might present, the youngest audience sector sees something quite different, and indeed rather terrifying.

Lurçat’s research remains valuable three decades later, in part because few others have concentrated so exactingly on the responses of the child viewer to a single anime. We might suggest that there are elements of the Hawthorne effect here, which is to say that the very fact that the respondents were the subject of an experiment led them to articulate positions that would not have otherwise troubled them. This is not to detract from Lurçat’s [image error]achievement; even if some of her respondents merely give the answer they thought they should, Lurçat’s collated responses provocatively argue that a television can be a horrific device that invades the sanctity of childhood.

Lurçat’s study is also notable in that the word ‘Japan’ is not mentioned at any point. Unlike Ségolène Royal’s politically motivated tract, Le ras-de-bol des bébé zappeurs (1989), which articulates media violence as an unwelcome foreign import in France, Lurçat entirely ignores the nationality of her cartoon subject. True to the formalism of Reader-Response, Lurçat spends no time wondering how Goldorak came to be, who made it, or what kind of channel it has landed on. Indeed, she does not even explain what Goldorak is, apparently expecting her readership to already know its plot and themes; readers that do not may only interpret them through the stumbling explanations of the infant interviewees.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade.

Hugo, Boss

The new, free, online edition of the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction has just won the Hugo Award for Best Related Book. I take some small part of the glory, having written some 100,000 words of it. Which sounds impressive until you realise that the whole thing is already at 3.7 million words, and still growing.

This new edition incorporates substantially more information on China and Japan. to the extent of an entire book-within-a-book on such subjects as mecha and the Seiun Awards, and authors such as Liu Cixin and Wei Yahua. Best of all, it includes the magical Incoming button, which not only tells you all the entries that link *to* the entry you were looking at, but also formats a reference for a researcher’s bibliography.

August 26, 2012

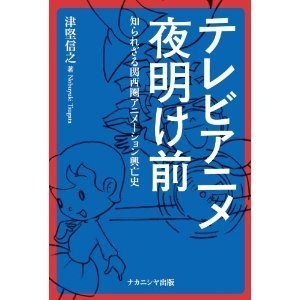

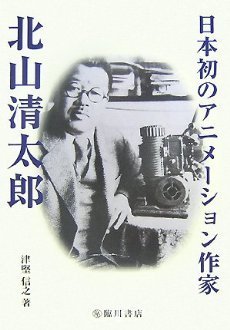

Before the Dawn

Nobuyuki Tsugata has already published books on the careers of Osamu Tezuka and the pioneering animation of Seitaro Kitayama, as well as broader studies of anime history as a whole. Last year he co-edited Anime-gaku, the first truly successful attempt to discursively construct ‘anime studies’ as an object of knowledge, delineating Japanese animation as a field of academic enquiry in and of itself, rather than as a subset of film, business, culture, media or any other discipline. And while far too many of his international colleagues continue to fritter away their lives in endless studies of What Some Fans I Met Think of Some Anime They’ve Seen, Tsugata continues to soldier on in the dusty archives of anime history and biography, rescuing forgotten sectors of the business, and mounting persuasive arguments that expand the nature of anime as we know it.

Nobuyuki Tsugata has already published books on the careers of Osamu Tezuka and the pioneering animation of Seitaro Kitayama, as well as broader studies of anime history as a whole. Last year he co-edited Anime-gaku, the first truly successful attempt to discursively construct ‘anime studies’ as an object of knowledge, delineating Japanese animation as a field of academic enquiry in and of itself, rather than as a subset of film, business, culture, media or any other discipline. And while far too many of his international colleagues continue to fritter away their lives in endless studies of What Some Fans I Met Think of Some Anime They’ve Seen, Tsugata continues to soldier on in the dusty archives of anime history and biography, rescuing forgotten sectors of the business, and mounting persuasive arguments that expand the nature of anime as we know it.

As so often happens in the media, artistic heritage is often left in the hands of the people who made it in the first place – usually because nobody else really cares until it’s too late. Japanese animation history is dominated by the twin big-bangs of Toei Animation and Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Pro, in part because they resulted in works and workflows that can still be found today. What about all those other studios that fell by the wayside or didn’t have a publicity-hungry manager at the helm? What about all those studios that churned out work that never got collated on DVD or shown at film festivals?

As Tsugata notes in the introduction to his latest Japanese-language book, Before the Dawn of Television Anime, it’s like some areas on the map of anime history are still marked terra incognita. Many people have at least heard of TCJ (Television Corporation of Japan), mainly because this commercial animation company, since renamed Eiken, is still at work today, most famously as the production house that makes the TV series Sazae-san. But TCJ’s advertising past, usually dismissed in a single line before discussion of its TV programming output, was truly massive, amounting to more than 1400 cartoon adverts between 1954 and 1960 (and more than 2200 if you include those live ads for which TCJ provided animated diagrams or titles).

As Tsugata notes in the introduction to his latest Japanese-language book, Before the Dawn of Television Anime, it’s like some areas on the map of anime history are still marked terra incognita. Many people have at least heard of TCJ (Television Corporation of Japan), mainly because this commercial animation company, since renamed Eiken, is still at work today, most famously as the production house that makes the TV series Sazae-san. But TCJ’s advertising past, usually dismissed in a single line before discussion of its TV programming output, was truly massive, amounting to more than 1400 cartoon adverts between 1954 and 1960 (and more than 2200 if you include those live ads for which TCJ provided animated diagrams or titles).

Tsugata’s focus is not merely on forgotten byways of anime history, but also on forgotten geography. Although it is widely known that the Japanese animation industry, along with many other forms of production, relocated to the Kansai region after the devastating Tokyo Earthquake of 1923, Tsugata argues that Kansai remained the centre of Japanese animation for the next three decades, only ceding primacy to Tokyo with the establishment of Toei Animation in 1956. His narrative picks delicately at the Tokyo-centred bias of other Japanese books, pointing out that many landmark events in Japanese media, including, for example, the irresistible rise of Osamu Tezuka, actually ‘happened’ in Kansai. He also notes that Toei’s own press and self-commemoration has largely overshadowed the achievements of Saga Studio, a Kansai start-up, also established in 1956, which played a highly influential role in the first decade of Japanese animated commercials.

Tsugata diligently chronicles the perils of anime historiography. The men and women who churned out thousands of cartoon commercials in Kansai were not part of the academic conversation about what anime was. Hardly anyone has bothered to remember their work, because their work was usually the bit that happened in between the TV shows, and before the main features that anime historians actually bother to write about. This is despite the fact that the Kansai area studios turned an impressive buck, undeniably formed a part of the 1950s zeitgeist, and displayed a mastery and economy of line that must have made animation in the 1950s look considerably less ‘Japanese’ than it did after 1963. Tsugata’s cover includes one such image from several dotted throughout his book: a charming, dynamic layout of a pilot scattering leaflets from his plane, drawn as part of an Osaka Eiga commercial for a local prefectural election.

Tsugata has never been afraid of doing the legwork, scraping information from wherever he can. In his biography of Seitaro Kitayama, he famously reconstructed part of Kitayama’s 1920s studio output in true Blade Runner style, by enlarging a staff photograph to read the schedule stuck to the wall in the background. For Before the Dawn of Television Anime, he diligently tracks down the surviving industry veterans, now with an average age of seventy, and gathers testimonials that restore much of the Kansai story to narratives of anime history.

Tsugata has never been afraid of doing the legwork, scraping information from wherever he can. In his biography of Seitaro Kitayama, he famously reconstructed part of Kitayama’s 1920s studio output in true Blade Runner style, by enlarging a staff photograph to read the schedule stuck to the wall in the background. For Before the Dawn of Television Anime, he diligently tracks down the surviving industry veterans, now with an average age of seventy, and gathers testimonials that restore much of the Kansai story to narratives of anime history.

These teams, often working out of pokey six-mat rooms and identifiable only by the occasional initials in the corners of their sketches, were responsible for the animation in some of the iconic Japanese adverts of the 20th century, including commercials for Nisshin Cup Noodles, Vick’s Cough Drops and Matsushita Electrics. Some of their works were 90-second narratives, others merely ten instructional seconds inside a commercial filed as “live action”, but with a little animated section explaining how cockroach spray works, or how menthol clears out your tubes. They were also responsible for the creation of iconic characters such as Yanbo and Mabo, the twin tykes who shilled for Yanma Diesel, ubiquitous in the 1960s but forgotten now because they didn’t appear in the kind of anime that gets archived or remembered.

Tsugata’s narrative also fills in a gap in accounts of “art” animation, revealing how art-house animators like the award-winning Renzo Kinoshita actually paid the bills while tinkering with their high-brow creations. Far too many researchers seem to assume that art-house animators spend all day sitting in garrets playing with sandtables, supported by some magical and secret government super-subsidy, whereas many of them, including the Oscar-winning Kunio Kato, have day-jobs that often get left off the resumés that are sent to film festivals. I wish such information was made available more frequently, as it might smack a degree of realism into the aspirations of some arts students. Tsugata does not shy away from it, and reveals that far from working in an adman vacuum, the animators of the Kansai set had strong and often reciprocal connections with big-name animators like Noburo Ofuji and Hakusan Kimura (himself the founder of Osaka Eiga in 1960).

Tsugata finishes with an outline of the vestiges of the old Kansai anime tradition, as kept alive by such companies as today’s Kyoto Animation. He also returns to a subject familiar from some of his earlier books: the little-discussed admission that even the big names in Tokyo were keen on ad revenue to pay the bills. Tsugata has argued before that Toei Animation itself was set up partly in anticipation of the money that could be made from the expansion of commercial Japanese television in the 1950s, and staff from Mushi Pro have admitted that they used to get paid a lot better making adverts with Astro Boy in them, than they did making Astro Boy itself.

His conclusion recalled a passage I had read elsewhere, in the posthumously published memoirs of the animator Soji Ushio, who had once decided to visit the famous canal-side studio building where the renowned Iwao Ashida had made many of the big animated splashes of the 1950s. Instead, when he arrived at the address, the canal had been filled in, the studio itself had been turned into a tatami shop, and there was no sign of the man whose company Ashida Manga Eiga had once been the biggest name in the Japanese animation medium. How soon they forget.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade.

August 19, 2012

More at the SFE

I’ve been beavering away on the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, so there are a lot of new Japanese entries up on the site, including Koji Suzuki, Summer Wars, The Wings of Honneamise and Cowboy Bebop. And for China, the authors Huang Fan and Chang Shi-Kuo.

August 18, 2012

The Demonisation of Empress Wu

[image error]A lovely article has just been posted on the Smithsonian blog, outlining the odd life and hateful rumours about Empress Wu. There are a couple of quotes in there about shagging slave girls and barbecuing sheep, lifted from that book about her by one Jonathan Clements.

I think the article gives a remarkably good account of why she is such a fascinating subject, even so many centuries after her death.

Jonathan Clements's Blog

- Jonathan Clements's profile

- 123 followers