Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 24

November 13, 2010

Entering the Itano Circus

I'm pretty sure Ichiro Itano is going to punch me in the face.

I'm pretty sure Ichiro Itano is going to punch me in the face.

It's hard to tell, because I have a pair of opera glasses strapped to my head, the wrong way round, so that everything looks as if I am staring at it down the wrong end of a telescope. But in the round window of my vision, I very clearly see the director of Gantz, his hair tied back in a ponytail, his wiry muscles rippling under a khaki vest, hauling back his arm and then lurching right at me.

His fist speeds into view, looming huge in the frame. His arm seems to trail behind it for an impossible distance, while his hand blocks the entirety of my view. I stumble backwards, expecting a blow at any moment, but Itano has deliberately fallen a couple of inches short.

"Ha!" he says. "See? That's what the world looks like if you're the pilot of a giant robot! You're looking through a viewscreen, you see. You're not using your real eyes, you're using a camera! And so, when we show a pilot's-eye view in an anime show, we shoot it the way that a camera would see it!"

I lift the opera glasses gingerly and peer at him with my real eyes.

"That's what an action director does!" he continues, enthusiastically. "He puts you inside the action. Inside it! Not observing, but participating. That's why an anime director must always think outside the box. He must think himself into the places where no camera has been before."

Yes, I say timidly. Which brings me back to my original question. Why exactly did you strap fifty fireworks to your motorbike?

Itano looks at me askance, as if wondering if I am dim.

"Well," he says, "that was as many as I could fit. You know, some on the mud guards, some on the cowling, some on the –"

Yes, I say. I see that. But perhaps we are talking at cross-purposes about the meaning of "why". Why did you do it?

"Oh," he replies. "We'd been told that it was dangerous. So obviously, we decided to try it. I had my bike on the beach. And my friend had his, and we rode out a ways to give ourselves plenty of run-up, and then we charged each other. On the motorbikes."

And then, I ventured meekly, you lit the fireworks?

"That's right. They were all linked together with fuse cord, but I still had to light them. Did you know that a Zippo lighter is still windproof at eighty miles an hour? That's really impressive, isn't it?

"So anyway, I lit the fireworks, but they all kind of went off at once. There was this sudden, explosive cloud of smoke, and then there were rockets and firecrackers in my face, looping past me, around me… and it was really weird, sometimes they seemed to hang in space for a moment, as if they weren't going anywhere. It was because I was still moving, along with them. Relative velocities, you see! Some were moving faster, others slower. And the smoke trails behind them billowed out in yet another direction, carried off by the wind, which was blowing in its own direction, nothing to do with the direction my bike was going. Or not going. Because I fell off. And I think my clothes were on fire by this point.

"So, you know… that's a daft thing to do. Even if you're twenty years old and drunk, it's not recommended. The biking around on the beach is actually more fun than the actual fireworks… But I'm an artist. I put that experience to use. There was a storyboard on an anime show that had a pilot's eye view of missiles coming towards him. And I said, you know what, that's not what it looks like. It's not so linear. I've been in the middle of a bunch of rockets going off, and they snake all around you. They don't always go in the same direction! There are duds, and ones with unexpectedly high charges, and always smoke going in a direction you don't expect. So I put all that in, and in the show we got this massive explosion of rockets and contrails. And it was pretty good!

"Not long after, Kazutaka Miyatake gives an interview to My Anime magazine, and he mentions this kind of shot, and says that it's turning up all over anime. It's turning up in Macross, of course. This kind of three-dimensional positioning within a salvo of rockets, and he calls it an 'Itano Circus.' Named after me, you see! How about that?

"Now, for my next trick, I shall re-enact the opening of Star Wars with nothing but a mobile phone…"

Jonathan Clements is the author of Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade. This article first appeared in SFX Total Anime #3, 2010.

November 11, 2010

Two Today

The Schoolgirl Milky Crisis blog is two years old today. I'm going to keep posting stuff here until Titan Books grow bored with it. They will continue to think of this blog as a worthwhile expense for as long as people are buying the Schoolgirl Milky Crisis book, either here in the US, or here in the UK. So please do consider it as a Christmas present for your odder uncle or more eccentric aunt, that irritating sibling or that strangely with-it parent. Or even for yourself.

The Schoolgirl Milky Crisis blog is two years old today. I'm going to keep posting stuff here until Titan Books grow bored with it. They will continue to think of this blog as a worthwhile expense for as long as people are buying the Schoolgirl Milky Crisis book, either here in the US, or here in the UK. So please do consider it as a Christmas present for your odder uncle or more eccentric aunt, that irritating sibling or that strangely with-it parent. Or even for yourself.

November 7, 2010

Yoshinobu Nishizaki 1934-2010

Yoshinobu Nishizaki, who died today, was a colourful and controversial character in the anime world. Born as Hirofumi Nishizaki in the old samurai town of Aizu-Wakamatsu, he rebelled against his traditionalist family by founding a jazz club. By his late twenties, he had moved into music production, but suddenly switched careers to become an office manager for the "god of manga," Osamu Tezuka.

Yoshinobu Nishizaki, who died today, was a colourful and controversial character in the anime world. Born as Hirofumi Nishizaki in the old samurai town of Aizu-Wakamatsu, he rebelled against his traditionalist family by founding a jazz club. By his late twenties, he had moved into music production, but suddenly switched careers to become an office manager for the "god of manga," Osamu Tezuka.

Nishizaki claimed that he had fallen in love with Tezuka's comics, particularly the future trilogy of Lost World, Next World, and Metropolis. Joining Tezuka's studio, Mushi Produtions, Nishizaki threw himself into legal and operational work, and scored what he hoped would be a landmark success when he sold the rights of Tezuka's Marvellous Melmo to a TV channel. However, ratings were a disaster for the series, which attempted to turn sex education into a kids' comedy, and Nishizaki found himself taking the blame instead of the credit.

As Mushi Productions drifted towards bankruptcy, Nishizaki came to resemble the first mate on a sinking ship. Industry gossip associated him not only with the departure of many animators, but with the disappearance of company property. When Mushi's doors were shut for good, Nishizaki somehow sprang back into business as the owner of Anime Staff Room, a company that appeared to use talent and materials liberated from the beleaguered Mushi Productions. Nishizaki even managed to walk away from Mushi with intellectual property. One of Nishizaki's jobs at Mushi had been to register copyrights, and it appeared that although both Wansa-kun and Triton of the Sea bore Tezuka's name as creator, their ownership had somehow been assigned to Nishizaki. Depending on who you talked to, Nishizaki was either a canny accomplice who dutifully kept Tezuka's people working through a legal loophole, or a traitor who broke Tezuka's heart.

The anime business suffered its worst crisis since WW2 at the turn of the 1970s, with multiple studio collapses, a change in the value of the yen, and a recession brought on by the rise in Middle Eastern oil prices. Nishizaki likened the period to "a winter struggling towards spring," particularly after neither of his liberated properties recouped their production costs on broadcast. Tezuka, perhaps, had had the last laugh by not telling him a vital truth – that even Astro Boy had been produced at a loss, in the hope that merchandise and foreign sales would make up the shortfall. With no foreign sales forthcoming and reduced public interest in merchandise, Nishizaki was dead in the water.

But Nishizaki fought on. His most famous creation came in 1973, when he and two other Mushi refugees dreamt up a sci-fi quest narrative, Asteroid Ship Icarus, in which a crew of teenagers crewed a space vessel built within a hollowed-out asteroid. After the manga artist Leiji Matsumoto was brought in to refine the idea, this gradually transformed into Space Cruiser Yamato, in which a group of Japanese heroes embarked on a desperate mission across the cosmos, in a ship built from the hulk of a WW2 battleship. Eventually broadcast abroad as Star Blazers, the serial became a long-running franchise, and would eventually become the subject of a bitter court battle between Nishizaki and Matsumoto, as each claimed to be the true creator.

In the 1980s, Nishizaki changed his company name from Office Academy to Westcape Corporation (Japanese: "Nishi-zaki"), under which he became the executive producer of The Legend of the Overfiend, the first and most notorious of the "tits and tentacles" genre that repurposed animation for erotic horror. Despite soaring success in multiple foreign markets, not even the Overfiend could rescue Nishizaki's fortunes, and he would file for bankruptcy in 1997.

Shortly afterwards, he was incarcerated for a potent cocktail of cumulative offences: he had been smuggling illegal firearms into Japan while already on bail for possession of narcotics. He consequently spent much of the first decade of the 21st century in prison, and only recently returned to form with a new animated Space Cruiser Yamato movie, Yamato Resurrection. Ever one to look for a gimmick, he infamously focus-tested the ending with an audience of fans.

When I wrote the biographical entry on Nishizaki for the Anime Encyclopedia, I commented that he could sometimes seem to be a one-hit wonder, constantly returning to the Yamato as his only trusted source of revenue, and becoming increasingly spiteful in his claim to own the idea. But I also suggested that Nishizaki's greatest, as-yet untold story was his own autobiography: surely a tale fraught with enough scandal, drama and adventure for any TV series?

Nishizaki died as he lived, in a manner that was both odd and suspicious. The 75-year-old producer reportedly fell from his boat, the Yamato, in the harbour of Chichijima in the Bonin Islands, about 150 miles north of Iwo Jima. It is difficult to imagine that he is really gone. There are sure to be several figures in the anime industry who surely wonder if this is not yet another larger-than-life chapter in his life, and if Nishizaki might not suddenly reappear next week leading a band of pirates, or having discovered the fountain of youth. Some might even suspect it is a last-ditch moneymaking scheme: an attempt to encourage old-time enemies to speak out against him, all the better to return from the grave armed with libel suits.

Still, as the news spreads through the Internet and it appears not to be a cruel hoax, we are left with the news that 2010, anime's annus horribilis, has claimed yet another high profile figure. It is all the more ironic that Nishizaki should die at sea, even as the publicity machine gears up for the film that will now be surely seen as his final epitaph: the live-action Space Battleship Yamato movie that will have its official premiere on 12th December.

Unlike many anime figures, Nishizaki never published his autobiography. He did, however, write a brief memoir for the inaugural issue of My Anime magazine in 1981, in which he acknowledged that he was a volatile figure in the industry, but that his intentions had always been honourable.

"I have made many mistakes," he admitted. "But I have no regrets."

Jonathan Clements is the author of Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade.

November 6, 2010

Salon Futura #3

Issue #3 of Salon Futura is up online, and features my article about Yasutaka Tsutsui, the novelist known to most anime fans through the movie adaptations of Paprika, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time and most recently, Nanase Again. He's a man with a multifaceted career, and some truly unexpected achievements, so do check it out. There's also a fascinating article about a book on prehistoric science fiction, interviews, reviews… lots.

Issue #3 of Salon Futura is up online, and features my article about Yasutaka Tsutsui, the novelist known to most anime fans through the movie adaptations of Paprika, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time and most recently, Nanase Again. He's a man with a multifaceted career, and some truly unexpected achievements, so do check it out. There's also a fascinating article about a book on prehistoric science fiction, interviews, reviews… lots.

November 1, 2010

Grown-up Digital

Back now from the Helsinki Book Fair, an event that is sure to put a smile on the face of any author who's been told that book is dead. Unlike London's annual book fair, which is more about business and marketing junkets, Helsinki's is wide-open to the public, and all the books are actually on sale. I may have accidentally spent a hundred pounds on obscure Finnish historical works, as well as several CDs from the Valamo Monastery.

Back now from the Helsinki Book Fair, an event that is sure to put a smile on the face of any author who's been told that book is dead. Unlike London's annual book fair, which is more about business and marketing junkets, Helsinki's is wide-open to the public, and all the books are actually on sale. I may have accidentally spent a hundred pounds on obscure Finnish historical works, as well as several CDs from the Valamo Monastery.

I had been summoned to Helsinki by the Finnish publishers of my Mannerheim book. They wanted me to ride shotgun on Don Tapscott, a Canadian statistician and management professor whose Grown-Up Digital they were releasing that week in Finnish. Tapscott, who has a company that advises heads of state on futurist issues, had jetted in from Italy, where he'd been hobnobbing with Al Gore, and was giving the keynote address that afternoon to the VIA Forum, which comprised the serried ranks of Finnish CEOs, company directors and entrepreneurs.

I'd been seconded to the press conference, because Finns can be very shy when faced with a celebrity, and need someone to show them that it's okay to ask questions and argue. Although, my publishers needn't have worried. Tapscott strode into the room, sat on the desk and then talked for a solid hour with barely any prompting. He carries all his figures in his head, and is a persuasive, inspirational speaker on generational matters.

Tapscott has no time for airy theorising or impressionistic opinions. He has the data instead: data that says kids today genuinely do have different brains, genuinely are smarter and more pro-active than previous generations. He is eternally hopeful about the prospects for what he calls the Net Generation, even concerning such issues as piracy.

Tapscott is horrified that, he says, the third most lucrative business for the music industry is currently suing music lovers. He thinks that music should stop being about consumer goods and start being a service. He wants to see all the music in the world available for immediate streaming from a central server, to which the subscriber pays a mere two or three dollars a month. "Why," he says, "would you want to 'own' it when you can have it all?"

It would be a logistical nightmare in terms of access and micropayment management, but then again, the Authors' Licensing and Collecting Society already manages something similar for British books in libraries. It's merely a matter of scale. So there's a thought…

October 29, 2010

Takeshi Shudō 1949-2010

Takeshi Shudō, who died yesterday, was a scriptwriter on some of the best-known anime of modern times. After a stumbling start in scripting, he would eventually become the first recipient of a prestigious anime screenwriting award, and would go on to establish the dramatic voices of some of the most-watched anime characters of the early 21st century.

Takeshi Shudō, who died yesterday, was a scriptwriter on some of the best-known anime of modern times. After a stumbling start in scripting, he would eventually become the first recipient of a prestigious anime screenwriting award, and would go on to establish the dramatic voices of some of the most-watched anime characters of the early 21st century.

The son of an assistant prefectural governor, Shudō was born in Fukuoka, and spent his childhood in Sapporo, Nara and, eventually, Shibuya in Tokyo. His knowledge of this latter location would eventually be put to use in his scripts for Idol Angel Welcome Yoko (1990, Idol Tenshi Yōkoso Yōko), in which a pop star masqueraded as an anime superheroine. But his road to anime was a rocky one, and encompassed a false start in live-action.

After flunking his first set of university entrance exams, the teenage Shudō picked up his sister's copy of Scenario magazine, which intrigued him with its "how-to" articles on screenwriting. He was still only 19 years old in 1969 when he sold his first script, an episode of the long-running live-action ninja-cop TV show Oedo Dragnet, a.k.a. Oedo Untouchables. However, his script was pilloried, not least by Shudō himself, for its "surfeit of unconvincing emotions," and no further work was forthcoming. He drifted through a number of sales jobs in Japan and Europe, before a meeting with the prominent screenwriter Fukiko Miyauchi gave him a second chance, writing "Sly Coyote", an episode of the anime series Cartoon Folktales of the World (Manga Sekai Mukashi-banashi), broadcast on 18th November 1976.

After working on some other serials for Dax International, he moved to Tatsunoko Productions and then Ashi Pro (now known as Production Reed) in the 1980s, where he was an instrumental writer on several new serials. Although both Idiot Ninja (Sasuga Sarutobi) and I'll Make a Habit of It! (Chō Kuse ni Narisō) were based on works by manga creators, Shudō put his mark on them as lead screenwriter, coining catchphrases and the comedy business that would become his trademark. In 1983, his work on these shows and others would secure him the first Anime Grand Prix Screenwriting Award, an honour that would later be conferred on the likes of Kazunori Itō and Hayao Miyazaki.

Shudō's most enduring influence was arguably his creation of Fairy Princess Minky Momo, one of the first of the new generation of "magical girl" shows, refashioning the Japanese folktales of Momotarō for an audience of young girls. Particularly successful in France and Italy, where she is known as Princess Gigi, Momo was able to transform into an adult version of herself, taking on various jobs in the grown-up world. Other series that featured his work included Legend of the Galactic Heroes and Martian Successor Nadesico.

Shudō also worked as a novelist, largely on books spun off from anime shows. He wrote many of the Goshōgun novels, nine volumes of the fantasy series Eternal Filena, and the first two books that novelised the Pokémon series. Pokémon was Shudō's most identifiable work for modern audiences. As with his the successes of his youth, it was not his personal creation, but he still injected many recurring tropes and comedy elements that would come to define the series. He wrote the screenplay for Pokémon: The First Movie (1998), one of the best-selling anime videos of the decade in many territories, including the UK, where it sold over 360,000 copies.

On 28th October 2010, he collapsed in the smoking area of the JR Nara train station. He was rushed to hospital for emergency surgery, but died several hours later from a subarachnoid haemorrhage. At the time, he had been working for the companies Gonzo and Dogakobo on a new cheerleader "character project" called Cheer Figu!, although its precise nature (anime, computer game, manga?) remains unclear.

Shudō's death deprives the anime world of yet another of its creators, in a year that has already taken the lives of several prominent figures. Moreover, it further diminishes the dwindling population of 20th century anime screenwriters. The Anime Grand Prix for Screenwriting was only awarded for seven years in the 1980s, and four of its recipients have already passed away, including Susumu Takaku (1933-2009) and Hiroyuki Hoshiyama (1944-2007).

Jonathan Clements is the author of Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade.

October 26, 2010

Judge Dee Fights The Power

From Wu, by Jonathan Clements, available in the UK and the US. Recommended reading if you want to get the most out of Tsui Hark's new Dee movie, set at the time of Empress Wu's coronation.

—-

Judge Dee was rounded up with a number of other officials, and escorted to the investigators' head office by the Gate of Beautiful Scenery. Lai Chunchen informed his captives that they had one shot at mercy – under plea-bargaining terms that Empress Wu had recently approved, anyone who immediately pleaded guilty could have their sentences commuted from execution to banishment. With that in mind, Lai Chunchen asked Judge Dee if there was a conspiracy. Dee's reply was blunt and sarcastic:

[Wu's] Great Zhou revolution has occurred, and ten thousand things are changing. Old officials of the Tang dynasty like myself are soon to be executed. You bet there's a conspiracy!

Lai Chunchen would have preferred a straight yes or no, but took Judge Dee's response to be in the affirmative. Dee was locked up for processing, although his stance managed to impress some of his captors. One investigator, doubting very much that Dee would be detained long in exile, asked him if the judge would put a good word in for him on his return, to which the judge responded by literally banging his head against a wooden pillar while calling the investigator a series of rude names.

The Judge, however, was not going to go without a fight. Waiting for a moment when he was left alone, he wrote a letter to his son on the inner lining of his jacket, and then prevailed upon his captors to take the jacket back to his home, so that his family could take out the winter padding.

On finding the secret message, Dee's son immediately applied for an audience with Wu herself, and showed the empress the accusing letter. Lai Chunchen was called to explain himself, but argued that the letter was a forgery, since he had no record of the judge's clothes being sent back to his house. There, Dee's case might have foundered before it could have truly begun, but for a slave who approached Wu himself. The ten-year-old boy was one of many palace servants who owed their position to the alleged misdeeds of their elder family members. Uncaring that his words could lead to his own torture or death, the boy announced that his family was innocent, and that he lived his life as a slave solely because of the persecutions and lies of the 'cruel clerks.'

This dramatic turn of events forced Wu to summon Dee to the palace to explain himself. She asked the judge why he had pleaded guilty in the first place, to which Dee replied that it was the only way he could avoid torture and death.

October 21, 2010

Starting Point

Starting Point is often technical, and frequently curmudgeonly, as one might expect from a collection of essays, articles and speeches by the Oscar-winning Hayao Miyazaki. The book spans a critical two decades, beginning when he was a busy but unknown anime director, and ending as he prepared to release his acclaimed Princess Mononoke.

Starting Point is often technical, and frequently curmudgeonly, as one might expect from a collection of essays, articles and speeches by the Oscar-winning Hayao Miyazaki. The book spans a critical two decades, beginning when he was a busy but unknown anime director, and ending as he prepared to release his acclaimed Princess Mononoke.

A welcome change from press-release puffery and anodyne publicity interviews, Starting Point offers an unwavering glimpse of Miyazaki's white-hot intellect and ardent creative beliefs. A recurring theme is his seething hatred for television, the medium that paid the bills during his twenties, while leeching much of the creativity from the anime world. Miyazaki is fiercely critical of the production line system instituted in the 1960s, and rues the day anime stopped being an organic, evolving process, in which artists would snicker over storyboards like comics, before working them up into sketches. By the time he left TV in disgust to make Castle of Cagliostro, animators were just the guys who painted and traced, relentlessly working on a sausage-machine of production, with creativity left to nobody but a paltry handful of senior staffers. And even they were trapped within the confines of budgets, advertisers, and stuffed shirts who Miyazaki has no qualms about calling stupid.

But that's half the fun in a beautifully produced, intensely brainy collection of rants and raves from the undisputed master of modern Japanese animation, rendered even stronger by a peerless translation from Beth Cary and Frederik L. Schodt. If one must quibble, a bitty compilation like this, brimming with reportage and incident, really ought to have an index. But even so, this is a mandatory purchase for the serious anime fan.

This review first appeared in SFX Total Anime #3, 2010.

October 18, 2010

Choc Shock

So that's Scotland Loves Anime done and in the bag, and me off to get the afternoon train to London. It's been a great nine days that's seen me interviewing Satoshi Nishimura and Shigeru Kitayama in Glasgow, and discussing Translation at Edinburgh University — some very impressive and inspiring students there, including one who did some amazing MSc work comparing professional work and fansubs, and who's got his just reward, a cushy job in Frankfurt localising for Nintendo.

So that's Scotland Loves Anime done and in the bag, and me off to get the afternoon train to London. It's been a great nine days that's seen me interviewing Satoshi Nishimura and Shigeru Kitayama in Glasgow, and discussing Translation at Edinburgh University — some very impressive and inspiring students there, including one who did some amazing MSc work comparing professional work and fansubs, and who's got his just reward, a cushy job in Frankfurt localising for Nintendo.

Friday was the Education Day at the Edinburgh Filmhouse, where I led 20 Animation students through the miseries of production accounting, legal, packaging, and broadcasting. Within two hours, they were pitching a 13-episode TV series about evil overlord Tone Def and his incompetent space pirates trying to steal chocolate from Earth, and held off by an alien pop group, while I enumerated all the reasons they were going to get sued. There was much shouting and laughter, but also, I think, a bit of learning going on. And so we have Choc Shock, to add to previous workshops' story ideas such as Decontaminators (from the Irish Film Institute) and Hattie Bast: Mummy's Girl (from Screen Academy Wales). This time, we incorporated recent unexpected discoveries I have made about the correlations between TV ratings and the longevity of toy lines, based on claims made by Tokyo Movie Shinsha's Keishi Yamazaki in his book Terebi Anime Damashii.

On Friday afternoon, we had Nik Taylor from Rockstar talking about the development of Grand Theft Auto 4, and Oscar Wright from Scott Pilgrim taking us frame-by-frame through the film's anime inspirations. I found this particularly fascinating, not only for his excerpts of influential cartoons, games and comics, but for the debates over how many frames onscreen sound effects should be held for. Then a panel about finding work in the industry, in which Helen Jackson of Binary Fable joined us to discuss the applications of student skills in the real world. A fantastic day. Meanwhile, Michael Sinterniklaas has been around all weekend, discussing dubbing and localisation on several panels, and taking a bow at the screening of Summer Wars, for which he has just recorded the lead voice in the English dub. He's a force of nature, bubbling with industry insider information, and peppering his stories with a thousand voices. He's back in England for next week's London Expo, and I think fans are in for a treat.

From Friday night onwards there were more screenings to introduce: Redline for a boggled crowd, followed by a screening of Professor Layton that was entirely transformed by a bonus giggling lady in the audience. Also, I appeared to be sitting in front of Admiral Ackbar, who kept saying: "IT'S A TRAP!" Sunday morning was an unexpected and illuminating encounter with Joe Peacock, who talked me through the Akira exhibition that has been at the Filmhouse all week — including some amazing original cels that show nine planes of movement.

Scotland Loves Anime has been an incredible success — there were people in town who had travelled from as far afield as France for the premiere of The Disappearance of Haruhi Suzumiya; we had entertaining Japanese guests for Trigun; Redline made everyone feel like they'd been shot out of a cannon; the Education Day was truly educational, and everything rounded off with a sold-out screening of Akira. As festival director Andrew Partridge said himself, would Katsuhiro Otomo have ever imagined a packed screening for his film in the capital of Scotland, 22 years after its original release?

And now, at last, I can get some work done… except I have to be in Finland by Friday for the Helsinki Book Fair, where I am interviewing Don Tapscott. So it's a week that starts with Haruhi Suzumiya and ends with Grown-up Digital.

October 15, 2010

Glory Days

Age and youth were important factors in the music of Yutaka Ozaki. He captivated the hearts of an entire generation of Japanese teenagers, but his obsession with teen years hid a great personal insecurity. Ozaki sung of the empty victory of graduation, but never finished school himself; he wrote of adults waiting to seize children's minds, but also took kids' money as part of the adult music machine. Ozaki was that saddest of popular heroes, a teen idol who preached nonconformity, who could only watch in terror as he slowly outgrew his audience.

Age and youth were important factors in the music of Yutaka Ozaki. He captivated the hearts of an entire generation of Japanese teenagers, but his obsession with teen years hid a great personal insecurity. Ozaki sung of the empty victory of graduation, but never finished school himself; he wrote of adults waiting to seize children's minds, but also took kids' money as part of the adult music machine. Ozaki was that saddest of popular heroes, a teen idol who preached nonconformity, who could only watch in terror as he slowly outgrew his audience.

The teen Ozaki was the only Ozaki that he, or anyone else was interested in, and the release of this CD collection reflects that. The Teenbeat Box isn't a Greatest Hits, it's a collection of the recordings that Ozaki made while still a teenager, and it places great weight on these early years, even to the extent of listing the live performances he gave before he hit twenty. Many pop stars find themselves in difficulty when their original audience becomes too sophisticated for them, and Ozaki became a Peter Pan figure, perpetually railing against authority. He could never have returned to do a concert in his forties; his successful portrayal of youthful rebellion was also his undoing, in that as his youth left him, so did the validity of his lyrics.

His career began in 1983 when he dropped out of high school to release his first single. Ozaki had taught himself to play the guitar while holed up at home, supposedly hiding from the school bullies, and he became a model of polite rebellion for many Japanese youths.

His idea of rebellion was nothing unique in itself. On Seventeen's Map, "The Night" talks of his desire to ride a 'stolen motorbike, uncaring into the darkness'. More famously, he suggested eloping, with one of his most popular songs, "I Love You". Depicting a couple who have sacrificed everything so that they can be together in a seedy apartment, it is a moving example of Ozaki's songwriting ability; unfortunately it's not such a good example of his singing. The uncredited session musician who sings "I Love You" on Kodansha's singalong Sing Japanese album is actually a better singer than Ozaki ever was, but Ozaki's raw quality was part of his appeal. "I Love You" is a beautifully tragic song, and Ozaki's constantly-cracking voice is supposed to be evocative both of his youth, and of the tearful words of the song.

His idea of rebellion was nothing unique in itself. On Seventeen's Map, "The Night" talks of his desire to ride a 'stolen motorbike, uncaring into the darkness'. More famously, he suggested eloping, with one of his most popular songs, "I Love You". Depicting a couple who have sacrificed everything so that they can be together in a seedy apartment, it is a moving example of Ozaki's songwriting ability; unfortunately it's not such a good example of his singing. The uncredited session musician who sings "I Love You" on Kodansha's singalong Sing Japanese album is actually a better singer than Ozaki ever was, but Ozaki's raw quality was part of his appeal. "I Love You" is a beautifully tragic song, and Ozaki's constantly-cracking voice is supposed to be evocative both of his youth, and of the tearful words of the song.

A more interesting factor in Ozaki's songwriting, throughout his career, was the way he ran lyrics together. Lines in Ozaki songs tend to be longer and harder to enunciate than usual. It requires a very particular control of one's breathing to make sure there's enough oxygen in the lungs to manage some of the longer stanzas, which involve two or three lines intoned without pause for breath. It's a peculiar style, but nonetheless one that served Ozaki well.

Other songs on Seventeen's Map include ballads like "My Little Girl", rock songs like "Scenes of Town", and even a rock-reggae fusion in High School Rock and Roll. The follow-up album, Tropic of Graduation, contains my favourite Ozaki song, the bittersweet "Graduation". It begins as a valedictory song, the sort of self-congratulatory, well we've made it through school, looking forward to getting a job, let's still be friends, number that would be on the karaoke machine at the any bar near any school until the end of time. 'At last we're free.. from fighting the adults in disbelief, we have the freedom we so desperately wanted'. But "Graduation" turns nasty very fast, as the happy, proud student suddenly starts asking difficult questions: 'What happened to our dreams? Where do we put our anger now?' The threshold of adulthood is not regarded with hope or eagerness, but with a bitter elegy for, literally, the best years of the singer's life. This is particularly relevant, both to the early 80s when Japanese youth started to question the measure of success in getting a steady career, and in Ozaki's own life, because his pop stardom meant that he never finished school himself.

Other songs on Seventeen's Map include ballads like "My Little Girl", rock songs like "Scenes of Town", and even a rock-reggae fusion in High School Rock and Roll. The follow-up album, Tropic of Graduation, contains my favourite Ozaki song, the bittersweet "Graduation". It begins as a valedictory song, the sort of self-congratulatory, well we've made it through school, looking forward to getting a job, let's still be friends, number that would be on the karaoke machine at the any bar near any school until the end of time. 'At last we're free.. from fighting the adults in disbelief, we have the freedom we so desperately wanted'. But "Graduation" turns nasty very fast, as the happy, proud student suddenly starts asking difficult questions: 'What happened to our dreams? Where do we put our anger now?' The threshold of adulthood is not regarded with hope or eagerness, but with a bitter elegy for, literally, the best years of the singer's life. This is particularly relevant, both to the early 80s when Japanese youth started to question the measure of success in getting a steady career, and in Ozaki's own life, because his pop stardom meant that he never finished school himself.

There's more of the same in "Bow!", in which he compares the rebels-without-a-cause around him with 'Don Quixotes drunk with youth… talking too much of their dreams till dawn arrives.' Dawn is adulthood, and Ozaki's children have wasted the long night with empty activities. Ozaki may be a Japanese youth icon, but his words are often identical to those of the Japanese adults. On one level, Ozaki's songs are an exercise in rebellion, but since he never makes an adverse comment about adult life, merely ironic comments on the emptiness of youthful dreams, you could argue that he was really on the side of his grown-up producers and management.

I would argue that Ozaki's lyrics have a lot more in common with Bruce Springsteen's ironies in "Glory Days" and "Born in the USA". He bids farewell to youth, then stops and wonders why he should bother; and if it isn't worth saying goodbye to one's teens, is it really worth saying hello to one's twenties? This inversion of traditional ideas also comes across in some of his compositions. "Dance Hall" describes a scene of wild and crazy teens, dancing their hearts out at a rock club, drinking, smoking, and blowing their meagre cash on juvenile entertainments. But it's not a fast rock number, it's a ballad, as if Ozaki, in slow motion, were watching the frenetic kids in realtime, wanting to be dancing in their midst, but too melancholy to do anything except stand apart.

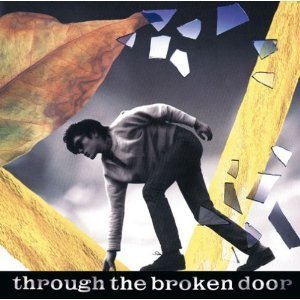

As Ozaki's teens drew to a close, he released Through the Broken Door, which had no perceptible change in attitude. He was doing well enough, and if it ain't broke, don't fix it. Thus the album begins with "Rules on the Street", in which our now-familiar rebel asks 'where now?' Familiar in many ways, because by this time Ozaki's rebellion seems rather bland. The anger that informed "Graduation" is nowhere to be seen; he still sings of teenage angst, but in a half-hearted way that shows by this stage he was on autopilot. But such an autopilot brings some moving, if manufactured, ballads with it. Forget-me-not has the same chordic arrangements and elegiac quality of the Commodores' "Three Times a Lady", although while the Commodores sung of a couple looking back upon an entire lifetime together, Ozaki's singer only looks back on his teen years.

As Ozaki's teens drew to a close, he released Through the Broken Door, which had no perceptible change in attitude. He was doing well enough, and if it ain't broke, don't fix it. Thus the album begins with "Rules on the Street", in which our now-familiar rebel asks 'where now?' Familiar in many ways, because by this time Ozaki's rebellion seems rather bland. The anger that informed "Graduation" is nowhere to be seen; he still sings of teenage angst, but in a half-hearted way that shows by this stage he was on autopilot. But such an autopilot brings some moving, if manufactured, ballads with it. Forget-me-not has the same chordic arrangements and elegiac quality of the Commodores' "Three Times a Lady", although while the Commodores sung of a couple looking back upon an entire lifetime together, Ozaki's singer only looks back on his teen years.

By the time he came to record Through the Broken Door, Ozaki had a proper backing group, the 50s rock-and-roll-influenced Heart of Klaxon. This introduced a greater degree of professionalism into his songs, but only insofar as they began to take on the appearance of bland MOR tunes to match the bland lyrics. So why is it that I like Through the Broken Door most of all? Maybe I'm getting old myself, who knows? "Grief", or to translate the title literally, "Him", is a paean to a dead friend and a lost time, someone who 'embraced the asphalt' in an unspecified, drug-related accident, all the more effective in its pathos by depriving the listener of the gory details. It is a serious "Leader of the Pack", without the campy chorus.

"Doughnut Shop" is a facile hymn to love at first sight, in a location that removes much of the romantic ambience, but there's something about the final track, "Someone's Klaxon", which transcends the material on the rest of the album. Tellingly, it's no longer Ozaki's lyrics, which lost their edge a year before, but his musical maturation. Someone's Klaxon uses minor keys to great effect, and has all the feel of a warm, melancholy yet satisfying tune. You could almost say that the singer had finally found peace, and was ready to face the rest of his life without another scowling backward glance. It was a fitting ballad with which to end Ozaki's teens, and the best track on Through the Broken Door.

As a grown-up, Ozaki painted himself into a corner with his angst-ridden wish to never grow old. True to form, his life was over when he could no longer hold back the tide of adulthood. He died of a drug overdose in 1992. He was twenty-seven.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade. This review-article was written in 1996 for Anime FX, although the magazine was shut down before it could appear. It is published here for the first time.

Jonathan Clements's Blog

- Jonathan Clements's profile

- 123 followers