Sara Ahmed's Blog, page 2

March 6, 2023

#KilljoySolidarity

The Feminist Killjoy Handbook is out in the world! Bringing it out into the world has taken time – and my blog has been quiet during that time. I am glad to share its arrival here. Please do order the book from independent bookstores, many of whom have got behind the handbook: you can find a list here. If you do read the book, share a picture on twitter (using the hashtag #wearefeministkilljoys). It means so much to me to know the handbook is in your hands.

We launched the book at an event in Rich Mix, London, on Thursday, March 2nd 2023. It was electrifying and emotional to be with so many people – killjoys, colleagues, affect aliens, trouble makers, friends. Each of us can be all of the above! And we filled the room with our killjoy solidarity. And, it gave me a chance to think more about what I mean by killjoy solidarity. Killjoy solidarity is how I sign my letters, in Killjoy Solidarity, Sara, kiss, kiss. But it means much more than a way of signing or signing off. For me, killjoy solidarity is the solidarity we express in the face of what we come up against. In the handbook I offer what I call killjoy truths, or hard worn wisdoms, what we know because of what keeps coming up. Let me share the last truth offered in the book, which probably best explains what I mean by killjoy solidarity.

Killjoy Truth: The More We Come up Against, the More We Need More.

The more we need more. Sometimes, being feminist killjoy, can feel like coming up against it, the very world you oppose. Killing joy, naming the problem, becoming the problem, can make us feel alone, shattered, scared. I think of a student who wrote to me from a very painful place, giving me a trigger warning for the content she was to share. At the end of her letter, she said “My killjoy shoulder is next to yours and we are a crowd. I cannot see it at the moment, but I know it’s there.’ I love the idea of a killjoy shoulder, becoming feminist killjoys as how we lean on each other.

We cannot always see a killjoy crowd. But we know it’s there. And we are here.

That’s one reason I wrote The Feminist Killjoy Handbook, to say, we are here. Although I have written about feminist killjoys before, the handbook is first book I gave them of their own. I made their book a handbook, because I think of it as a hand, a helping hand, an outstretched hand, perhaps also a killjoy shoulder, or a handle, how we hold on to something. A history can be a handle. It can help to know that where we are, others have been. When we travel with feminist killjoys, going where they have been, feminist killjoys become our companion. We need this companionship.

Killing joy can take so much out of us, the energy and time required to name the problem, let alone to become one. My emphasis in the handbook is also on what killing joy can give back to us. Whilst being a feminist killjoy can be messy, and confusing, it can also lead to moments of clarity and illumination, sharpening our edges, our sense of the point, of purpose. In addition to killjoy truths (those hard worn wisdoms), I offer killjoy equations (what is revealing and quirky about our knowledge) killjoy commitments (the wills and won’ts of being a feminist killjoy) and killjoy maxims (the dos and don’ts). In the second chapter, I also offer some killjoy survival tips; my first tip to surviving as a feminist killjoy is to become one.

To become a feminist killjoy is to get in the way of happiness or just get in the way. We killjoy because we speak back, because we use words like sexism or transphobia or ableism or racism or homophobia to describe our experience, because we refuse to polish ourselves, to cover over the injustices with a smile. We don’t even have to say anything to killjoy. Some of us, black people and people of colour, can killjoy just by entering the room because our bodies are reminders of histories that get in the way of the occupation of space. We can killjoy because of how we mourn, or who we do not mourn, or who we do mourn. We can killjoy because of what we will not celebrate; national holidays that mark colonial conquest or the birth of a monarch, for instance. We can killjoy become we refuse to laugh at jokes designed to cause offense. We can killjoy by asking to be addressed by the right pronouns or by correcting people if they use the wrong ones. We can killjoy by asking to change a room because the room they booked is not accessible, again.

Killjoy Truth: We have to Keep Saying It Because They Keep Doing It

Note that negativity often derives from a judgement: as if we are only doing something or saying something or being something to cause unhappiness or to make things more difficult for others. Killing joy becomes a world making project when we refuse to be redirected from an action by that judgement. We make a commitment: if saying what we say, doing what we do, being who we are, causes unhappiness, that is what we are willing to cause.

Killjoy Commitment: I am willing to cause unhappiness.

But it can be hard, precisely because the negativity of a judgment sticks to us, because eyes start rolling before we even say anything or do anything as if to say, she would say that.

Killjoy Equation: Rolling Eyes = Feminist Pedagogy

She would say that; we did say that.

Even if we say it, killjoy solidarity can be hard to do. I learnt so much about killjoy solidarity by talking to those who did not receive it. I am thinking of the conversations I had with students and early career lecturers who, having made complaints about sexual harassment by academics, did not receive solidarity they expected from other feminists, often senior feminists. Why? It seemed that those senior feminists did not want to know about something that would be inconvenient for them, which would get in the way of their work or compromise their investments in persons, institutions or projects.

Killjoy Commitment: I am willing to be inconvenienced.

It is not so much that killjoys threaten other people’s investments in persons, institutions, or projects. We become killjoys because we threaten other people’s investments in persons, institutions or projects. And “other people” can include other feminists. And “other people” can include ourselves. Killjoy solidarity can also be the work we have to do in order to be able to hear another person’s killjoy story. We need to be prepared for our own joy to be killed, our progression slowed, if that is what it takes.

So yes, the negativity of the judgement can stick to us. It can slow us down, make our lives more difficult.

I think also of the negativity of words such as queer, which have historically been used as insults, and that are full of vitality and energy because of that. Reclaiming the feminist killjoy is a queer project. A killjoy party, a queer party, is a protest. I wanted to have a party, also a protest, to launch the book because of how many of us are under attack, our claims to personhood dismissed as “identity politics,” our critiques as “cancel culture,” our lives treated not only as light and whimsical, lifestyles, but as endangering others, as recruiting them. These attacks, which are relentless, designed to crush spirits, are directed especially to trans people right now. I express my killjoy solidarity to you, today and every day. It can be exhausting having to fight for existence.

Killjoy Truth: When you have to fight for existence, fighting can become an existence.

And so, we need each other. We need to become each other’s resources. Feminism can or should be such a resource. But what goes under the name of feminism, at least in the UK right now is anti-queer as well as anti-trans, willing to use categories such as sex or nature or natal to exclude some of us, categories that many of us have long critiqued. We say no to this. That no is louder when we say it together. A book can be a no to this. We keep writing, keeping fighting, knowing that we are sending our work out into the hostile environment that we critique.

We say no even when we know it is hard to get through.

We say no together, to make room for each other.

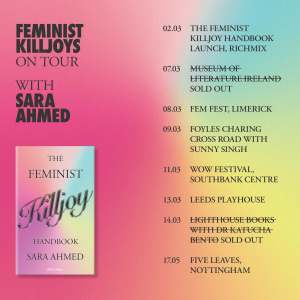

I am glad to be embarking now on a book tour, which we are calling Feminist Killjoys on Tour (you can find some of the events listed here).

If I am near you, come by and let us share some #killjoy solidarity. I want to say thanks, too. I left my post, my profession, my life really, back in 2016. I am profoundly grateful to all of the readers who have stayed with me because you have made it possible to dedicate my time to writing, to become a killjoy writer.

For me #killjoy solidarity is also how we thank each other for what we help make possible for each other.

I think of the feminist killjoy as a shared resource for living strangerwise. Strangerwise, is an odd world for an old wisdom, the wisdom of strangers, those who in being estranged from worlds, notice them, those who in being estranged worlds, remake them.

In fighting for room, we make something for ourselves.

Killjoy Truth: To make something is to make it possible.

Possibility can still be a fight because we have to dismantle the systems that make so much, even so many, impossible. Still, this truth is closest to what I call killjoy joy. Killjoy joy is how it feels to be involved together in crafting different worlds. We need joy to survive killing joy. We find joy in killing joy. I think of all the letters sent to me by feminist killjoys, how we reached each other. I think of what I have learnt from picking the figure of the feminist killjoy up all those years ago, and putting her to work. When I think these thoughts, I feel killjoy joy. Perhaps we find killjoy joy in resistance, killjoy joy in combining our forces, killjoy joy in experimenting with life, opening up how to be, who to be, through each other, with each other. Killjoy joy is its own special kind of joy.

In killjoy solidarity,

Sara xx

September 20, 2022

Feminism as Lifework: A dedication to bell hooks

A lifework: the entire or principal activity over a person’s lifetime or career. To be a feminist is to make feminism your lifework. I am deeply indebted to bell hooks for teaching me this – and so much else, besides. I write this post in dedication to bell.

When bell hooks died, I couldn’t bring myself to write about her, what her work meant to me, to the students I have taught over many years, to those with whom I share a political project and community. I read what others wrote, grateful that for some of us grief does not take away the capacity for description. For me, it takes time for words to come, to get to a point when I can say something about losing someone. You can lose someone with meeting them. Or, you can meet someone through what they gave to the world.

Words are coming out because of what you gave to the world. In Talking Back: Thinking Feminism, Thinking Black, hooks wrote of writing as “a way to capture speech, to hold on to it, keep it close. And so, I wrote down bits and pieces of conversations, confessing in cheap diaries that soon fell apart from too much handling, expressing the intensity of my sorrow, the anguish of speech, for I was always saying the wrong thing, asking the wrong questions. I could not confine my speech to the necessary corners and concerns of life. I hid these writings under my bed, in pillow stuffings, among faded underwear” (1988, 6-7). In writing, by writing, bell hooks refuses to be confined. She spreads her words, herself, all over the place.

All that intensity, it goes somewhere. The pages fall apart from “too much handling.” The paper is cheap, the material she has available. She makes do; she gets through. The pages wear out because of how they matter. To write is how she spills out, spills over, the intensity of sorrow, filling it up, stuffing it where she can, where she is, the places she has, under the bed, in the pillow cases, among her underwear, under, in, among; hidden with delicates, her other things. In putting her writing there, her thoughts and feelings tumbling out, what she hears, “bits and pieces of conversations,” she exceeds the space she has been given, the concerns she is supposed to have, allowed to have, the corners, the edges of the room.

We are asking the wrong questions when we question a world that gives us such little room.

There is much beauty in bell hooks’s writing about writing, in her description of what is wearing about the work, about the words. And, there is pain, too.

hooks writes of how you can be caught out by others who think they have found something out about you by finding your words. She mentions how her sisters would find her writing and end up “poking fun” at her (7). She describes leaving her writing out as like putting out “newly cleaned laundry out in the air for everyone to see” (7). Note she does not talk about dirty laundry, that expression often used for the public disclosure of secrets. This is cleaned laundry; it is hanging out there because of labour that has already been undertaken. When writing is labouring, it is what we do to get stuff out there, to get ourselves out there. There is still exposure of something, of someone, in the action of airing, making your interior world available for others to see.

To spread yourself out can be to go back in time, to pull yourself out by pulling on those who came before. hooks describes how as a Black girl she had to stand her ground, defy parental authority, by speaking back. She also describes how she claimed her writer-identity, “One of the many reasons I chose to write under the pseudonym bell hooks, a family name (mother to Sarah Oldham, grandmother to Rosa Bell Oldham, great-grandmother to me” (9). Penning your own name can be how you claim a Black feminist inheritance. Defiant speech, too. Elsewhere, hooks describes how her grandmother was “known for her snappy and bold tongue” (1996, 152). Writing can be writing back but also writing from, to be snappy as to recover a history.

In Talking Back, hooks also writes about memory, sharing a memory of how her mother remembered, “I remembered my mother’s hope chest with its wonderful odour of cedar and thought about her taking the most precious items and placing them there for safe keeping. Certain memories were for me a similar treasure. I want to place them somewhere for safe keeping” (158). Smell can travel through time; we remember something by smelling it. And an object can hold our memories, keep them for us, so we can return to them. For hooks, memories are not always clear or even true. She tells us she remembers “a wagon that my brother and I shared as a child” (158). But then she tells us her mother says, “there had never been any wagon. That we had shared a red wheelbarrow.”

A wagon, a red wheelbarrow. The question isn’t which one was it. Objects acquire different colours and shapes, depending. And writing too; how objects acquire different colours and shapes, depending. You might be a red wheel barrow or a wagon. The question isn’t which one. Sometimes, in loosening our hold on things, also ourselves, we bring them to life. In a conversation with Gloria Steinem, bell hooks describes how she is surrounded by her own precious objects, feminist objects. They are the first things she sees when she wakes up. She says “the objects in my life call out to me.” And then she says she has “Audre Lorde’s ‘Litany for Survival’ facing me when I get out of bed; I have so many beautiful images of women face me as I go about my day”.

Feminism becomes how you create your own horizon, how you surround yourself with images that reflect back to you something precious and true about the live you are living or that life you have lived.

A story of survival, of persistence, also love.

Writing, too, hooks shows us, can be how we surround ourselves.

We write ourselves into existence. We write, in company. And we write back against a world that in one way or another makes it hard for us to exist on our own terms. When I think of what it takes to write back, who it takes, I think of how many came before us who laid out paths we could follow. And I think of you. It can be good hap to find you there. Sometimes, it takes my breath away when I think of how easily we can miss each other.

We write because we are missing something. We write to help us find each other. In reflecting back on her life-saving book Feminism is For Everybody, bell hooks tells us how her commitment to feminism grew over a lifetime. The preface to the second edition begins, “Engaged with feminist theory and practice for more than forty years, I am proud to testify that each year of my life my commitment to feminist movement, to challenging and changing patriarchy has become more intense” (vii). I like how you didn’t write “the feminist movement,” but “feminist movement.” Without the “the,” we can hear the movement. I think of the encouragement you give us in sharing this testimony. You teach me that we can find a way through the violence of this world by sustaining our commitment to changing it. To sustain – even intensify – our commitments to feminism is a political achievement given that what we try to challenge and to change, others defend, others who have the resources to turn their defence into an instruction. To express your feminist commitments has life implications – you end up at odds with so much and so many. You also taught me that to be “at odds” is not simply about what is painful and difficult – it is also an opening, an invitation even. That is how you defined queer after all, “being at odds.” What might seem like the negative task of critique, naming what we oppose, showing how violence is implicated in the most cherished of cultural forms, is thus an affirmative task of creating room so that we can live our lives in another way.

In telling this story of her lifelong commitment to feminism as a politics of changing the world, bell hooks addresses us, her audience. She notes that her books were “rarely reviewed,” but still “found an audience.” She describes how she is “awed” that her work “still finds readers, still educates for critical consciousness” (viii). When feminist books are not reviewed by the newspapers with wide circulation or displayed in the front of the bookshops because they are too dissident, how do we find them? hooks suggests her own books were found by “word of mouth” and through “course adoptions.” I found bell hooks through the latter. Her work was assigned in a class I took in 1992 (the teacher who assigned bell hooks was Chris Weedon, thank you Chris for that assignment). Any so by word of mouth or by being taught in feminist classrooms, bell hooks’ books found their readers and saved our lives.

How we find bell hooks is not unrelated to what she has to teach us. Finding feminism is not about following the conventional paths that lead to reward and recognition. Your definition of feminism is “the movement to end sexism, sexual exploitation and sexual oppression” (2000, 33). From this definition, we learn so much. Feminism is necessary because of what has not ended: sexism, sexual exploitation, and sexual oppression. And for hooks, “sexism, sexual exploitation and sexual oppression” cannot be separated from white supremacy and capitalism. That is why, you keep naming it, what you oppose. In Outlaw Culture, hooks made use of the term “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy” an impressive eighteen times! No wonder you have given me so much killjoy inspiration! You named it, nailed it, every time!

There can be costs to nailing it. I think again of hooks awe that her books found their readers. There is a story we can glimpse here of what bell hooks did not do to “find” her audience. In a public dialogue with Marci Blackman, Shola Lynch and Janet Mock at the New School in 2019, hooks says, “I say to my students: Decolonize. But there’s also that price for decolonization. You’re not gonna have the wealth. You’re not gonna be getting your Genius award funded by the militaristic, imperialist MacArthur people.” hooks clarifies that she is not speaking against those individuals who accept these awards but rather pointing to how to decolonise our dependency is to create our own standards for living. To receive funding or prizes or fellowships from organisations whose power derives from the system you critique is to accept a limitation. Even if you think of yourself as working the system it can be hard not to end up working for the system.

You taught me that to change the system we have to stop it from working. I think of that price, the price we pay for the work we do.

Feminism too can end up being the avoidance of that price. We have to find another way through feminism. I think of how bell hooks’s critiques of white feminism gave us so many tools, for instance, her critique of Betty Friedan’s solution to the unhappiness of the housewife, the “problem that has no name” (except of course, you named it). You write, “She did not discuss who would be called in to take care of the children and maintain the home if more women like herself were freed from their house labor and given equal access with white men to the professions” (2000, 1–2). And you taught me how to “do feminist theory” by reflecting on what happens when we “do feminism.” You describe a meeting “a group of white feminist activists who do not know one another may be present at a meeting to discuss feminist theory. They may feel they are bonded on the basis of shared womanhood, but the atmosphere will noticeably change when a woman of colour enters the room. The white women will become tense, no longer relaxed, no longer celebratory” (2000, 56). In this description there is so much insight into everything. A woman of colour just has to enter the room for the atmosphere to become tense. Atmospheres – they seem intangible mostly. But when you become the cause of tension, an atmosphere can be experienced as a wall. The woman of colour comes to be felt as apart from the group, getting in the way of a presumably organic solidarity.

There are many ways we can be removed from the conversation. That removal creates a feeling of unity. That some feminist spaces are experienced as more unified might be a measure of how many are missing from them. You taught me to notice who is missing, which is how we become killjoys, getting in the way of the occupation of space.

You taught me to be willing to get in the way.

You taught me to teach.

Teaching is how we learn, but also how we do the work of transformation. You write of teaching as how we model social change and as “the practice of freedom…that enables us to live life fully and freely” (1988, 72). I always taught your work. I taught your work in every year I taught, watching students be transformed by it. We often read your article, “Eating the Other.” I had drawn upon it in one of my first books, Strange Encounters, in an oddly titled chapter, “Going Strange, Going Native.” This is your description, “The commodification of Otherness has been so successful because it is offered as a new delight, more intense, more satisfying than normal ways of doing and feeling. Within commodity culture, ethnicity becomes spice, seasoning that can liven up the dull dish that is mainstream white culture” (1992, 21). “Ethnicity becomes spice” is perhaps one of the most perfect descriptions of how racism operates in consumer culture! You taught me in this piece how to theorise whiteness, how it becomes not only absence but neutral, a dull dish, how people of colour become spice, adding something, flavour even, added on, tag on, that goes on.

I kept being taught by you.

Did I tell you that?

I did not communicate directly with bell hooks. I did send bell hooks a message once by writing to her publishers South End in 2009. I wrote, “I know you have published works by one of our contemporary scholars and activists whom I most admire: bell hooks. I myself am a feminist of color working in and from the British and Australian context. I have been very influenced by bell hooks’ work, especially in my book Strange Encounters (2000), which drew on her wonderful critique of the exoticizing of otherness. It has been such a privilege and pleasure to work with her work.” They told me they passed this letter on to you, but I don’t know for sure if they did. And I wished I had written to you again. But then I think there was a sense in communicating to you through writing not addressed to you but to “feminist movement.”

We are that movement.

It was when I wrote Living a Feminist Life that I felt the fullness of my debt to you. That book had your handprints all over it, signs of what I could do because of what you had laboured to show, what you had left out for us to see. I remember putting your name on the top of the list of scholars who I would love to endorse that book never imagining you might say yes. When I first saw your words about my work I almost fell out of my chair. I was profoundly moved to know that you had read my work let alone that you had endorsed it.

And then my publisher put a sentence from you on the front of the book!

It said, “everyone should read this book.”

I still feel overwhelmed when I see the cover of Living a Feminist Life. Because I see it and I see your name. I see it and I see you. I am about to send out another book, The Feminist Killjoy Handbook, also addressed to feminist movement. You appear all over this book, in the chapter on surviving as a killjoy, the feminist killjoy as poet, the feminist killjoy as activist. I dedicate that last chapter to you.

There are many ways we communicate in writing our love for the world we are bold enough to want for each other.

Thank you bell, for what you helped me to see.

To be bold enough to want.

In killjoy solidarity,

Sara xxx

References

hooks, bell (2014). Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics. Second Edition. London: Pluto Press.

hooks, bell (2006). Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations. New York: Routledge.

hooks, bell (2000). Feminist Theory: from Margin to Centre. London: Pluto Press.

hooks, bell (1996). “Inspired Eccentricity: Sarah and Gus Oldham” in Sharon Sloan Fiffer and Steve Fiffer (eds), Family: American Writers Remember Their Own (ed.), New York: Vintage Books.

hooks, bell (1992). Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston: South End Press.

hooks, bell (1988). Talking Back: Thinking Feminism, Thinking Black. Boston: South End Press.

June 8, 2022

The Complainer as Carceral Feminist

I am often asked how my arguments about complaint activism relate to the projects of transformative and restorative justice as well as abolitionist feminism. In an answer to one such question, I spoke of my caution in using some of these terms to describe some of this work because I had heard of how they can be misused in institutional settings. But I also said that complaint activism “has much more kinship with these other projects including abolitionist projects than it might appear at first” because you are thinking about “how to have accountability, how to deprive people of institutional power, and thus how to build relationships that are about enabling some people to get into, and stay in, institutions that would otherwise remain inaccessible.” I also noted that even if I did not use these terms, the “kinship” between the projects would become obvious “further along the line.”

In this post, I want to go a little further along that line by considering the figure of the complainer as carceral feminist. In my conclusion, I will turn to the important new book Abolition. Feminism. Now, by Angela Davis, Gina Dent, Erica R. Meiners and Beth E. Richie to explore the kinship between abolitionist feminism as they describe it and the work of complaint collectives formed to get complaints about harassment and bullying through the systems designed to stop them.

Let me begin with my own implication. I have been called a carceral feminist because of the support I gave to students who made a collective complaint about sexual harassment and (probably more importantly) because I gave that support in public. During the enquires into sexual harassment that led me to resign, and after I resigned, I was sent many letters and messages, overheard many conversations on social media and in person, and read public posts calling me a carceral feminist. Sometimes the accusation came with a psychological profile: that I envied the professors who were the objects of complaint, that I wanted what they had, their students, their centre, for myself. In one public post, I was described as an all-powerful, punishing and vindictive person who had singlehandedly tried to destroy another professor’s professional and personal life. So, I recognize the figure of the complainer as carceral feminist from being assigned her. And, I know how it feels to be called something you oppose because of how you oppose something.

As soon as I began the research, I found that I had company. So many people I spoke to who made or supported a formal complaint (especially when the complaints were about sexual harassment or sexual misconduct by academics) had been called carceral feminists. Why? Making a formal complaint at a university is not the same thing as calling the police. It is not about sending people to prison. So why does this figure appear when formal complaints are being made? What is she doing?

Let’s assume in the first instance that formal complaints are treated as carceral because they can lead to an investigative and disciplinary process, and, at least potentially, to a penalty being enforced by an authority. The figure of the complainer as a carceral feminist might be exercised to imply that the point of a complaint is punishment or penalty. In her brilliant book We do this ‘Til we Free us, Mariame Kaba differentiates punishment from consequences. For Kaba, punishment means “inflicting cruelty and suffering on people.” In contrast, “Powerful people stepping down from their jobs are consequences, not punishment. Why? Because we should have boundaries. And because the shit you did was wrong and you having power is a privilege. That means we can take that away from you. You don’t have power anymore.”

Kaba’s work is an invitation to ask hard questions about the nature of institutional power. You have institutional power when the position you are given by an institution gives you power over others. In the sixth chapter of Complaint! I consider institutional power in terms of who “holds the door” to the institution, who can determine not only who gets into the institution, but who progresses through it. Those who abuse power often represent themselves as generous, as willing and able to open the door for others. In a gift is lodged a threat to shut the door on anyone who will not do what they want them to do.

How, then, do we deprive someone of institutional power? It is precisely because some people have that power that it is hard to deprive them of it. If to deprive someone of institutional power is an institutional outcome, then to deprive someone of institutional power has to involve the institution in some way; it is a commitment to an institutional process of some kind. But having institutional power also means you can mobilize the institution’s own resources to stop those who are trying to stop you from abusing that power. Those who “hold the door” to the institution can and do shut that door on those who complain.

This is why to complain about an abuse of power is to learn about power: complaint as feminist pedagogy.

I want to stress at the outset that most people I spoke to did not want to punish the person or persons they were complaining about and if anything explained their reluctance to complain as concern about what the consequences would be for those they were complaining about. Why complain, then? Most people I spoke to complained about conduct for the simple reason that they wanted it to stop. A student who complained about the most senior member of her department said she “wanted to prevent other students from having to go through such practice.” Wanting the behaviour to stop is also about wanted what happened to you not to happen to others. This is why I describe complaint as nonreproductive labour, the work you have to do to stop the same things from happening, in other words, to stop the reproduction of an inheritance.

We are learning something about consequences – to stop someone often requires stopping the system from working.

What then is the framing of a complaint as about punishment rather than consequences doing?

Let’s take an example. I spoke to an academic who supported a collective of students who made a complaint about the conduct of a lecturer in her department. She describes the process, “a student, a young student, who came and said to me that this guy had seduced her basically. And then in conversation with another woman she found out he had done the same to her. And then it snow-balled and then we found out there were ten women, he was just going through one woman after another after another after another.” The professor defended his own conduct thus, “He come up to me and said, ‘it’s a perk of the job.’” I could believe it. He actually said it to me. It was not hearsay; this is a perk of the job. I can’t remember my response, but I was flabbergasted.” We need to learn from how “perk of the job” can be mobilized as a defence against a complaint about sexual harassment and sexual misconduct. The implication is that having sex with your students is like having a company car; what you are entitled to because of what you do.

A complaint can then be interpreted as a contradiction of an entitlement: the right to use or to have something. To deprive someone of power is to deprive them of what they experience as theirs. The women who made the complaint were quickly framed as motivated by a desire to punish. As the professor I spoke to describes, “The women: they were set up as a witch-hunt, hysterical, you can hear it can’t you, and as if they were out to get this guy.”

To deprive someone of power is understood by those with power as punishment.

As soon as you try to deprive someone of power, you will be identified as motivated by a desire for power. That identification is often used because it often succeeds. In this case, the complaint was not upheld and the lecturer returned to his post with minor adjustments to supervisory arrangements.

The framing of complaint as punishment can be a way of avoiding consequences.

It is convenient to pathologize the complainer as having a will to power.

Madeline Lane-McKinley has offered an important critique of what the framing of complaint as carceral is doing. She describes how the one who complains, “will be told you are putting someone else on trial. This is precisely what enables sexual abusers, for instance, to claim they are being witch-hunted, while mobilizing a witch-hunt themselves.” Lane-McKinley identifies a “carceral anti-feminism,” which names “all feminism carceral.”

When appeals to other forms of justice are made, this identification of feminist complaint as carceral is kept in place. Complaints can be framed as the failure to resolve the situation by other more positive means. I think of one student who was sexually assaulted by a professor. In consultation with the students’ union, she submitted an informal complaint. It was sent to a dean who told her she should “just have a cup of tea with him to sort it out.” Another student told me how it took repeated complaints by her and other students about the conduct of a professor before those complaints got uptake. And after the complaint got uptake, and a disciplinary process began, she was told by a colleague that “she should have used restorative justice,” with restorative justice being indexed weakly rather like that “cup of tea,” a loose and light signifier of reconciliation.

Note the suggestion “she should have used restorative justice,” was not made by someone speaking from or on behalf of an institution. It was made by a feminist colleague. In a recent virtual panel on transformative justice, a survivor described how the language of transformative justice was “misused” as “a network of support” for her abuser. As many feminists know, the system is already designed as a support system for abusers. What we also need to know is that support is being enacted by the use of critical feminist language. I remember how we were told after the enquiries took place that we should have used transformative justice. That term was not just used weakly, it was divorced from its radical history. When you are told you should have used transformative justice in cases where those who have abused power have refused and still refuse to recognize the harm they caused, transformative justice is used as a way of avoiding accountability, the opposite way to how it is used by our communities as a demand for accountability.

The very argument that complaint = carceral feminism can justify a certain kind of relation to the institution that I would summarize as institutional quietism. I think of this problem as at least in part a problem of white feminism. Of course, it remains important and necessary to critique carceral feminism as white feminism – as Alison Phipps for instance has done. I am not offering these observations to contradict that critique. And yet, it still needs to be said: I have had a number of conversations with Black feminists and feminists of colour about being called carceral feminists by white feminists. White feminists justify their withdrawal of support from those who complain by using that very equation complaint = carceral feminism. In case this seems odd or surprising, remember there is a long history of Black women and women of colour being identified by white feminists as angry, punishing, mean and hostile. If the carceral feminist can be turned into a psychological profile, it can also become a racial profile. In an earlier post on the figure of the white friend, I noted how that white feminists often push Black women and women of colour to be more positive or conciliatory, a gesture that can sweep over racism and racial harassment as if it was a misunderstanding or a miscommunication, to protect their white colleagues or even themselves. White feminists might even suggest to those of us who are initiating or supporting complaints about bullying or harassment read such-and-such Black feminist on forgiveness (I know this because it happened to me). In my lecture, After Complaint I noted that many of the concepts we develop to critique how power works can be used to mask how power works. I suggested that “our terms,” can become screens, assertions of the right of some to occupy time and space.

Along with a critique of complaint as carceral feminism goes a certain kind of institutional fatalism (there is no point in complaining if the whole institution is going down or there is no point in complaining if the point is to bring it down). But of course, some have to complain in order to be able to get into the institution, to move through them, or to do their work. Institutional fatalism is only useful to those whose relation to the institution is not under threat or those who don’t need to complain to access the building. If not complaining or not “rocking the boat,” can be about how some people protect the good relations they have to those who allocate resources, as I argued in “Complaint as a Queer Method,” only some of us have such relations in the first place. In other words, the action that is avoided by the critique of complaints as carceral feminism would threaten a more positive relation to the institution.

Being against complaints as carceral as a matter of principle allows some people to present themselves as being oppositional without having to do anything or to give anything up.

Please note, I am not saying that not complaining is only about protecting a positive relation to the institution. There are many reasons not to complain including a lack of trust in the institution (as I will discuss in due course), or an unwillingness to commit to a process that is designed to remain confidential and internal to the institution. I am rather pointing to how a critique of carceral feminism can be used to mask the protection of a positive relation to the institution by enabling it to be expressed as if it was a radical stance rather than institutional complicity.

If the critique of the complainer as carceral feminist is used by those who are critical of the institution, the institution not only benefits from but often shares that critique. In one instance, a senior administrator explained the decision not to appoint someone with expertise in sexual harassment or equality to head an enquiry into sexual misconduct by a professor because they “did not want to be seen to be conducting a witch-hunt.” The professor was, unsurprising, cleared of any wrong doing by an enquiry led by someone who was sympathetic to him. A formal process is framed as a potential witch hunt by those given responsibility for conducting that process; consequences are avoided by being treated as punishment.

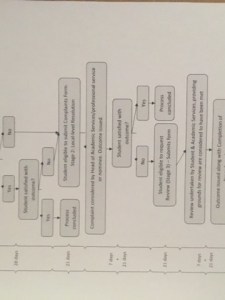

Is the push to be conciliatory another technique for avoiding consequences? I think back to the dean who told one student to “have a cup of tea” with the lecturer who had assaulted her. In the UK, the first stage of a formal complaint process is informal – and if your complaint is about an abuse of power you are encouraged to resolve the complaint in the department or unit where the abuse of power occurred. You are encouraged to identify that informality of the process in positive terms. I think of two students who met with administrators about their complaint. They describe what happened,

Student 1: They didn’t record it or take any notes. I think there were one or two lines written.

Student 2: It was very odd.

Student 1: You did feel it was a kind of cosy chat.

Student 2: Very odd; very odd.

Student 1: They were sort of wrapping the conversation up, because it had gone on, and I said this is us making a formal complaint and there was shift in the atmosphere. And I said we do want to follow it up as a complaint.

Informality can be used as a way of trying to discourage an informal complaint from becoming formal; turning a complaint into a casual conversation that can be more easily wrapped up. It is then as if the complainer is requiring an adherence to rules and conventions, or as if the formality necessary to make a complaint is itself a form of antagonism (not having a “cosy chat,” not being friendly). A formal complaint would become what someone makes because they are being unfriendly. Note how when the students make clear that they are making a formal complaint there is a “change of atmosphere.”

When universities direct those who are considering complaint to use more informal or less formal methods, they seem to do so to minimize harm and to demand compliance with the effort to restore the status quo. In one case, I talked to an academic who had make complaint, as had other members of her department about bullying by the head of the department. She described how they were invited to mediation, “the Pro-Vice Chancellor then said I am going to give you this gift, I have arranged for you to go to this hotel, and I have arranged for this person, a negotiator, to sit with you and sort this out. I had been bullied and called in so many times by this guy; I just thought I am not going to mediation meeting with this person.” Being invited to enter mediation is represented as a gift. The gift is proximity to the person who is being abusive, you are being asked to be in the same room as him, to sit with him, as if all you need to resolve the problem is time and proximity. The use of seemingly more positive methods such as mediation by institutions often translates into those who abuse power being given more opportunities to express themselves.

I am not saying that there is no place for mediation in conflict resolution. But abuse is not conflict, although it is often framed as such by institutions. In Complaint! I share many instances of how harassment and bullying are treated as conflicts between parties that can be resolved by mediation, as different viewpoints that ought to be heard, as if you are hearing different sides of the same story. I shared examples of sexual and physical assaults being described as styles of communication (one head of department who assaulted a colleague in a corridor was described in the report that cleared him of wrong doing as having “a direct style of management”). When assaults and other abuses of power are treated as styles of communication, complaints can be framed as misunderstandings (“it didn’t mean anything” is a common retort for a reason). More or better communication is then turned into a solution.

In making communication the solution, individuals become the problem. Talking about harm or hurt can be a way of not talking about institutional power. Talking about trauma can be a way of not talking about structure. I noticed how quickly during the enquiries where I used to work the term “vicarious trauma,” began to be floated around (popping up in dialogue and documents), as if we are a collective had traumatized each other rather than been infuriated by the institutional response to the complaints. I recall how the only support I was offered was therapy – including in the final communication from the Warden after I resigned. Even if that offer was motivated by a genuine concern for my wellbeing, you can see the problem: we become the location of the problem, yet again.

To locate a problem is to become the location of a problem.

Those who don’t become the problem are protected. Institutions in protecting themselves protect those whom they have already given power. In other words, they are protecting their investment. You don’t have to go through a complaint to know that institutions will do what they can to protect their investments. In fact, it is because of what some people know about institutions that they decide not to complain. If you don’t trust the institution, why would you go through a complaints process? This is an important question. But we also need to ask: what if the lack of trust in the institution is precisely what is being used by those with institutional power?

Those given power by institutions have a concerted interest in making them untrustworthy.

I talked to a group of students informally. They described to me how they were dissuaded from lodging a complaint about sexual harassment. They were told by academics in the department that any complaint would be repurposed by senior management as a tool to be used against “radical academics,” that the complaint would become a carceral tool in the sense of being used punitively to close them down. This was a very successful method: for the students to express what they felt, a political allegiance to the academics, being on the same side, against the same things, required them not to complain about the conduct of those academics even though they objected to that conduct.

Many of those who complain share this concern that their complaint will be used by hostile management to justify decisions that those they themselves would not make. Damn it, I share this concern! Having said this, my study of complaint also taught me that management can use any data in any way – positive data can be used to create the impression there is no problem (and if there is no positive data, institutions will create it, or use existing data very selectively) and negative data can be used to justify the withdrawal of support (and if there is no negative data, institutions will create it, or use existing data very selectively). What is important to note is that the concern about the use of the negative data of complaint is in turn instrumentalized. If that concern is used to stop complaints, it is also used to enable the conduct that the complaints, if they had been made, would have tried to stop. And then, those who do make formal complaints about harassment or bullying by academics are treated as managers, disciplining “radical academics,” trying to stop them from expressing themselves freely.

The implication that to complain is to become the manager or to call the manager invites potential complainers to see themselves in the terms they often oppose. The figure of the complainer as carceral feminist is closely related to the figure of the complainer as manager explored in chapter 5 of Complaint! These figures help explain what might seem at first like a curious finding: the use of the word neoliberal to dismiss complaints and, in particular, student complaints. One student who made a complaint about harassment by a professor in her ma program said, “My complaint was called neoliberal.” Her complaint was called neoliberal by other students in the program. The other students also said that the complainers “needed to be in ‘solidarity’ with those whose education was now being disrupted, not the other way around.” Neoliberalism can be mobilized to judge those who complain as motivated by self-interest. Not complaining about harassment from a professor then becomes judged as being in the collective interest, a way of holding on to the professor by keeping silent about his abusive behaviour. Note if complaint is framed as punishment because it would deprive someone of power, the complainer becomes a stranger, depriving others of what they want, in this case, the professor. You can be punished for that consequence. The student was also told it was questionable to complain, as to complain is to “turn to the institution” and to “seek support” from it. In other words, entering into an institutional process by submitting a formal complaint is framed in advance as institutional complicity. Some academics position themselves as working against the neoliberal institution, refusing to comply with its bureaucratic impositions. This positioning is convenient because it allows abuses of power to be framed as non-compliant, rebellious or radical.

Those with institutional power often represent themselves as against institutions.

The designation of complaint as neoliberal can be used to imply that to make a complaint is to behave like, or to become, a consumer. Another student who made a complaint about bullying and harassment from a professor in her ma program said, “The idea that would come up is that I was somehow being a very neoliberal person, the idea of the student as a stakeholder.” When a student making a complaint about harassment is treated as a student acting as a stakeholder, treating education as an investment, the university as a business, complaints about harassment are made akin to not liking a product. Complaints about harassment can be minimized and managed when filtered as consumer preference. She added, “Maybe I am just a perfect neoliberal subject. Or maybe I am a person who doesn’t want to be abused.” What is striking is what she is revealing: how not wanting to be abused, complaining about abusive behaviour, can be judged as being “a perfect neoliberal subject.” We need to learn from how neoliberalism can be used to picture the person who does not want to be abused and who acts accordingly.

I think the designation of the complainer as neoliberal is useful because so many of us working within educational institutions would make (or have made) critiques of neoliberalism as damaging institutions. If a complaint is designated as neoliberal, the complainer can be identified as damaging universities not because they damage their reputation, which would be a neoliberal model of damage, but because they threaten progressive educational values or even the idea of the university as a public good. One student who put in a complaint about harassment was told, “You are going to ruin any chance for this innovative work continuing.” The effort to stop a complaint can be justified as giving support to innovative work. We might think of institutional violence as happening over there, enacted by those who would or could direct that violence toward us, as critical thinkers, say, subversive intellectuals, even, but that violence is right here, closer to home, in the warm and fuzzy zone of collegiality, in commitments to innovation, radicality, or criticality, in the desire to protect a project or a program.

In most instances, the diagnosis of the complainer as neoliberal happens retrospectively, but it can also be made in advance in an effort to justify the conduct (and thus to stop complaints). An undergraduate student was persuaded to enter a sexual relationship with a senior man professor: “The first time he touched me he closed his office door. I thought it was strange that he closed the door. We weren’t doing anything wrong. I pondered, Why hide this? He informed me that the university’s ‘sex panic’ was the reason: predatory neoliberal policies encroaching on our freedoms. I nodded. The door remained closed after that.” Here the closed door is deemed necessary because of “neoliberalism policies” as well as “sex panic,” a term that associates neoliberalism with a narrow, moralizing, feminist agenda. Policies are treated as the police. It is implied that the door is closed because of how certain forms of conduct (such as having sex with your students, that perk of the job) have made rights into wrongs.

Feminism can thus be treated as part of a managerial and diplomacy regime that is imposed upon others to restrict their freedom. Equality can be dismissed very easily as audit culture, as tick boxes, as administration, as bureaucracy, as that which can distract us from creative and critical work and can even stop us from doing that work. I think the word neoliberal also becomes attached to other words, including feminist, prude, uptight, moralizing, killjoy, and policing. If these words seem far apart, remember neoliberalism is used to picture the complainer as individualistic. Being a prude, uptight, and moralizing can thus be part of that same picture: the person who is unwilling to give herself to others or to participate in a shared culture is judged as putting herself first. A complaint can then be treated as an imposition of will, as forcing your viewpoint upon others, depriving them of what they experience as theirs.

Force can then be framed as originating with the complaint, even when the complaint is about violence. The figure of the complainer is treated as a symptom of a more generalized structure of violence, whether institutional, managerial, neoliberal or carceral. When complaints against academics are made, they can pass themselves off very quickly as the ones being forced, being forced out or being forced into compliance by a disciplinary regime. The complainers are then treated not as protesting violence, but as enforcing it; the complainers become not only the managers, but the police, or the prison guards. I think this passing is successful because many academics identify themselves as potentially harmed by a disciplinary apparatus because of who they are or the beliefs they hold. If you have had an experience of the institution coming down on you, you might be sympathetic to those who frame complaints made against them as the institution coming down on them.

I am using the word passing deliberately here. Passing often works because it approximates something real. Of course, we do know that complaints can be used to discipline academics for their minority views or status. It might be on these grounds alone that we could say that complaints can be carceral feminism. But there is a but! I also know of instances where complaints against minoritized academics have been dismissed as an exercise of institutional power in problematic ways. In one example, a man of color left his post after complaints by students about harassment and bullying. His departure was publicly represented by his supporters as being a result of a complaint made by a single white student who didn’t like how he expressed himself. I spoke informally to the students who were involved in the complaint process. I learned from them that complaints were made not by one student but by a group of students, including students of color, and related to Islamophobia and racial harassment as well as sexual harassment and bullying. This is how the use of the figure of the privileged white complainer, we could even call her Karen, can stop students of color from being heard; it can stop complaints about racial harassment from being heard.

A complaint against a minoritized person is not always an exercise of power against that person because of their minority status. As many of us know too well, institutions reward abusive behaviour, often strategically misrecognizing harassment and bullying as expressive, eccentric, or even as signs of genius. Those of us who are not straight, cis white men are more likely to have doors opened to us when we reinforce those same patterns of behaviour. I do know of cases of complaints made against queer academics that are motivated by homophobia and received uptake given the hyper-surveillance of non-normative bodies. But I also know of cases where queer academics have framed complaints about their conduct as homophobia to deflect attention from abusive patterns of behaviour.

It is hard to tell the difference between those who pass themselves off as disciplined for dissidence and those who are disciplined for dissidence.

We also need to remember that many, even most, of those who repeatedly harass, or bully other people can and do frame complaints against them as motived, malicious or oppressive. They can then position themselves as minoritized by virtue of being the object of a complaint. I recently read an article that listed examples of academics who had been disciplined by universities for “not fitting,” with their regimes. In that list, a known harasser (I say known as the complaint file is in the public domain) was casually positioned next to a Palestinian academic who lost his tenure because of his critiques of Israel. That adjacency is telling us something.

That it is hard to tell the difference between those who pass themselves off as disciplined for dissidence and those who are disciplined for dissidence can be instrumentalised.

Even though feminism can be associated with neoliberalism as well as managerialism, it is worth noting that some feminists can be persuaded by this reframing of complaint as a disciplinary technique used against dissident academics. I have read many letters of support written by feminists on behalf of colleagues who have been accused of sexual harassment or sexual misconduct. We need to understand how this can happen. I think of one case. Multiple complaints were made by students against an academic man (who had a leading role in the national union), which included allegations of rape, sexual assault, domestic violence, and sexual harassment. Despite the number and severity of allegations, he was still able to convince many of his colleagues that he was the one being harassed. I spoke informally to the group who worked together to make those complaints. A professor said, “His narrative was apparently that he was being accused of making sexist comments and the ‘feminazis,’ us, were out to get him.” The case against him was also described as a witch hunt. This use of such terms will be familiar to feminists: we only need to consider how quickly #MeToo was framed in this way, as a persecution of innocent men by a feminist mob.

The lecturer also received support from feminist colleagues who wrote letters on his behalf without even hearing from the students who had made the complaints. Some of these feminists have public roles in challenging the culture of sexual harassment (for example in leading campaigns against the use of NDAs). And yet behind closed doors, they were given their support to those accused of sexual harassment. The professor I spoke to explains: “Many colleagues, about sixty-eight to seventy, came forward on his behalf to suggest that really, he was a ‘good guy,’ just a regular ‘Northern Cheeky Chappie,’ maybe a bit of a rough diamond. . . . They had no idea of what he was being accused of, other than what he offered up to them as his own narrative.” These exact descriptions, “rough diamond,” a “Northern Cheeky Chappie,” were used by academics (including feminist academics) in letters of support submitted on his behalf. We can hear what they are doing. They are intended as rebuttals. They are used to imply that the complaints derive from a failure of those who complained to appreciate how he was expressing himself. They are used to imply that the failure to appreciate how he was expressing himself was a form of snobbery or class prejudice. An early career academic from a working-class background described to me how enraging it was to be positioned as middle class, as if “working-class women never complained,” as if working-class women did not have their own militant feminist history and were not themselves instrumental in the battle to recognize sexual harassment as a hostile environment in the workplace in the first place.

I cannot overstate how painful and triggering it is when feminist colleagues who speak out against sexual harassment in public give their support to serial harassers when called upon to do so without even hearing from those who complained. Those who complain about harassment often end up feeling all the more stranded—they are all the more stranded—because the solidarity they expected to receive from those with whom they share an allegiance is withdrawn from them and given to those whose violence required them to complain in the first place. I think again of the survivor who shared how the language of transformative justice was “misused” to create “a network of support” for her abuser. I think of her; I thank her.

A critique of the misuses of the language of transformative justice can be understood as a contribution to the project of transformative justice.

We need to know that support for those who abuse power is being justified by the misuse of the language of transformative justice. We need to explain it. We need to contest it. And we need to create our own support systems.

Let’s return to Mariame Kaba’s description of consequences as depriving someone with institutional power. Those who complain come to know first hard about how hard it is to deprive someone of power in part through learning about what complaints do not do, where they do not go. Complaints procedures are atomising: most institutions do not allow collective complaints for a reason. We are made smaller by being kept apart. Confidentiality can also lead to isolation – you are not supposed to talk to anyone about your complaint or you are only supposed to talk to those with an institutional position. You can end up having to hold so much in. This is why I think of complaint activism as the work of getting complaints out.

The work of complaint teaches you how the system works. I think of one of the woman professors who participated in the complaint collective that was dismissed as a witch hunt. I was interested in where she ended up. She said, “By the end I just wanted to put a flame to the whole thing.” Going through what appears to be a purely bureaucratic or formal process, a tiresome, painful, difficult process, can be very politicizing, and sometimes then, energizing. Some of the strongest critiques of institutions come from those who have tried to make use of formal complaints to challenge abuses of power. When you make a complaint, you might not necessarily begin by thinking of yourself as part of a movement nor as a critic of the institution let alone as trying “to dismantle the master’s house” to evoke the title of Audre Lorde’s important essay. But that is where many who make complaints end up.

There is hope in this trajectory.

It is here that I can hear the kinship between the work of such complaint collectives and the abolitionist feminist project. Consider Angela Davis, Gina Dent, Erica R. Meiners and Beth E. Richie’s recent book, Abolition. Feminism. Now. I love how, in this book, they do not just write about abolitionist feminism but from it or even as it, creating a living feminist archive of a movement that is happening now, that is urgent, necessary, now.

Here is just one of their descriptions of abolitionist feminism:

For us, abolition feminism is political work that embraces this both/and perspective, moving beyond binary “either/or” logic and the shallowness of reforms. We recognize the relationality of state and individual violence and thus frame our resistance accordingly: supporting survivors and holding perpetrators accountable, working locally and internationally, building communities while responding to immediate needs. We work alongside people who are incarcerated while we demand their release. We mobilize in outrage against the rape of another woman and reject increased policing as the response. We support and build sustainable and long-term cultural and political shifts to end ableism and transphobia, while proliferating different “in the moment” responses when harm does happen. Sometimes messy and risky, these collective practices of creativity and reflection shape new are static identifiers but rather political methods and practices.

What I find so powerful about this description is how resistance is framed as a response to the relationality of state and individual violence. We have to find ways of responding that do not involve the expansion of reliance on institutions that cause harm such as the police or prisons. This does not mean abandoning accountability, but demanding it, being inventive, creating our own resources to try and bring an end to violence. Transformative justice is the work we do to create those resources. This is also how I understand the work of complaint collectives: it is about how we create and share resources, how we identify violence, including institutional violence, the violence of how institutions respond to violence, how we mobilize against it, how we work out how to bring an end to it by working together.

That work is also about showing how solutions are often problems given new forms. As Davis, Dent, Meiners and Richie also describe, “As new formulations surface, others fade; networks and groups proudly identify as feminist, queer, crip, Black, and/or abolitionist. Rattled by their demands and sometimes simply their formation, dominant institutions struggle to contain and manage these movements. But yet another “diversity committee” or another “equity officer” are inevitably failed efforts to contain these insurgent demands.” Complaint collectives are often formed because of how institutions try to manage complaints, often through positive injunctions such as diversity. To create a complaint collective is to work through the institution, but also against it, creating pockets in which we can breathe, as well as new relationships and alliances along the way. We imagine other kinds of institutions in the act of complaining about what happens in institutions, which are often also complaint about institutions, the kinds of institutions we have. Complaints can be a repurposing of negativity, a push to dismantle the institution from the inside out. From abolitionist feminism and from working in a complaint collective, I have learnt that a dismantling project is a building project.

We complain to make other institutions possible.

We know what is possible by fighting for it.

June 1, 2022

Feminist Ears

In today’s lecture, I will reflect back on my project on complaint, and in particular, my method of listening to complaint, listening as learning about violence. I was inspired to do this research after taking part in a series of enquiries into sexual harassment that had been prompted by a collective complaint lodged by students. I began working with the students in 2013, left my post and profession in 2016, started gathering testimonials in 2017 and published Complaint! in 2021. I am giving you the timeline because time matters, because during this time, almost a decade now, I have been immersed in complaint. I wrote the book from that immersion.

I describe my method as becoming a feminist ear. One academic wrote to me, “I want the complaint to go somewhere, rather than round and round in my head.” When a complaint goes round and round in your head, it can feel like a lot of movement not to get very far. To become a feminist ear is to give complaints somewhere to go. In time, I began to be addressed as a feminist ear. A student sent me a message. “I am writing because I need a feminist ear. Perhaps you can use this complaint in your work.” To become a feminist ear is not only to be willing to receive complaints but to make use of them, to do something with them, to make them work or to make them part of our work.

Before I turn to discussing my project on complaint, let me say a little about how I came to the idea of feminist ears. I first introduced this idea in my book, Living a Feminist Life. I was writing about the feminist film, A Question of Silence (Gorris, 1982). I was writing about snap, those moments you can’t take it anymore, when you lose it; I call snap a “moment with a history.” In this film the character Janine, a psychiatrist, is a feminist ear; she is listening to the stories of women who between them had murdered a man; she is listening to what they say, but also to silence, what is not or cannot be said. We listen with her, also through her, to sexism, the sounds of it, how women are not heard, how so often women might as well not be there, as secretaries, as wives, perhaps also professors, blanked when we say something, blanked because we say something. I will return later to how blanking can be used as a method for stopping complaints. The film shows how a feminist hearing is a shared action. Janine in hearing these other women’s stories, their complaints, begins to hear how she herself is not heard. She begins to see how she herself has disappeared from her own story, her life, her marriage, how her life is organised around him, his words, his work, his world.

It was only after I went to see this film during a feminist festival in London that I began to use the expression feminist ears. I was so struck by how loud the audience was especially during the scene when a man is congratulated after saying the exact same thing a woman secretary had just said – only to be ignored. The groan of the audience really hit me, that sound of recognition, of relief even. Why relief? So often we can’t quite put a finger on it, sexism say, or racism, even when we come up against it, even when it stops us from doing something, from being something, it is hard to show, to share what we know. It can be a relief to witness collectively what so often works by not being quite so visible or audible. The loudness of the audience was matched by the scene toward the end of the film in the courtroom, when Janine pronounces the women sane only to be met with the judge’s incredulity. The women in the courtroom begin to laugh, louder and louder still, because they can hear what the patriarchal judge cannot.

Feminism: we hear what each other can hear.

Feminism: we hear each other hear how we are not heard.

Feminism: we are louder not only when we are heard together, but when we hear together.

So, when I say that my method in researching complaint was to become a feminist ear, this becoming was not mine alone.

I spoke to a lecturer about what happened when she returned after long term sick leave. She is neuroatypical, she needs time, she needs space, to return to her work, to do her work. But the complaint takes so much time, so much work: “there are like four channels of complaint going on at the same time. But interestingly none of these people seem to be crossing over.” You have to speak to all these people who are not speaking to each other. She speaks to a physician from occupational health, “I think his sense was that if I was well enough to stamp my foot and complain then I was well enough to work.” Because she could hear how she was being heard, we too have the opportunity to hear something; how a complaint is audible as a tantrum; how the complainer is cast as spoiled; how a grievance is heard as a grudge. She describes what happened in the meeting, “[the physician] had to write a report on whether he thought I was fit for work, or what my problems were…he was shocked I think that I complained to him in the room face-to-face. He was dictating the letter to the computer, which was automatically typing it and I think he was astonished that I said I am not going to sign it.” I think of her refusal to sign that letter, to agree with how he expressed her complaint back to her, the words he reads out loud, his words, the computer automatically typing those words, his words; the different ways you can be made to disappear from your own story.

It is worth nothing here that complaint can be an expression of grief, pain, or dissatisfaction; something that is a cause of a protest or outcry, a bodily ailment, or a formal allegation. The latter sense of complaint as formal allegation brings up these other more affective and embodied senses. To complain you have to become expressive, the word express comes from press; to press out. Think of how she has to keep saying no, no even to how her no is recorded. It can be hard to keep saying no if you don’t feel you have a right to keep saying it, “There is something else which is something to do with being a young female academic from a working-class background: part of me felt that I wasn’t entitled to make the complaint – that this is how hard it is for everybody, and this is how hard it should be.” If part of her felt she was not entitled to complain, she has to fight all the more, she has to fight against that part of herself, that inheritance of a classed as well as gendered history; she has to fight to express her complaint in her own terms, she has to fight for what she needs to do her work.

To listen to complaint is to learn from those who are listening, to learn from those who have to fight to get into institutions, fight to be accommodated by them.

Feminist Ear as an Institutional TacticI mentioned earlier that this project was inspired by working with students who had put forward a collective complaint. I first met with the students in our department’s meeting room. They told me what had been going on. It was so much to take in. If to be a feminist ear is to take it in, a complaint is to let it out. Just after the meeting with the students, a feminist colleague came to my office. I told her some of what the students told me. She burst into tears. She said something like, “after all of our work this still happens.” There is so much feminist grief in this still, that the same things happen, still, despite everything, all that work, feminist work, our work, to try to change the culture of sexual harassment. We need time, also space, to express this grief, to turn it out and, sometimes, to turn it into complaint.

In the weeks following that first meeting, more students came to my office to talk to me. In an endnote in chapter 6, a little hidden, but it is there, I quote from a student “we’re all concerned that your office has become something of an emergency drop-in centre for women in various states of crisis. I hope you’re alright”. I am still touched by their concern. The students did not come to me because I had any special training or skills. I didn’t and I don’t. They came to me because I said I was willing to listen. They came to me because they had so few places to go. They came to me because the institution had already failed to hear their complaint.

It was a very noisy time. In one ear, I was hearing the institutional story of how well it was handling complaints, the story of equality and diversity, about what the university was committed to doing; I was receiving letters about how the university was going for an ATHENA bronze award for gender equality, would you like to participate Sara, we could use your expertise, Sara. In the other ear, I was hearing more and more complaints, more and more about violence, about institutional complicity, about previous enquiries that had not go anywhere; writing unanswered letters asking for a public acknowledgement that these enquiries had happened, asking for discussions of what they revealed, how sexual harassment had become part of the institutional culture. In one ear, in the other ear; the feminist ear is the other ear. If we can see through the glossy image of diversity, we can also hear through it, the buzz of it, to what is not being said, to what is not being done.

Becoming a feminist ear meant not only hearing the students’ complaints, it meant sharing the work. It meant becoming part of their collective. Their collective became ours. I think of that ours as the promise of feminism, ours not as a possession, but as an invitation to combine our forces. I am grateful that the students I worked with Leila Whitley, Tiffany Page, Alice Corble, with support from Heidi Hasbrouck, Chryssa Sdrolia and others, wrote about what the work they began as students in one of the two conclusions of the book. In the conclusion to their conclusion, they write about how they “moved something,” how “things are no longer as they were.” To move something within institutions can be to move so much. And it can take so much.

I decided to undertake this research before I resigned but I did not begin the research until after. My resignation, which I posted about on my blog, was widely reported in the national media. Whilst I found the exposure difficult, I was also moved and inspired by how many people got in touch with me to express solidarity, rage and care. I received messages from many different people telling me about what happened when they complained. I heard from others who had left their posts and professions as a result of a complaint. One story coming out can lead to more stories coming out. By resigning from my post, I had made myself more accessible as a feminist ear. Having become a feminist ear within my own institution, I could turn my ear outward, toward others working in other institutions.