Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 92

November 11, 2013

Veterans Day Tribute

A little patriotism is a good thing. And gratitude for sacrifices made and duty done is pleasing to God. Thanks to my father-in-law, my grandpa, my uncles, to all the veterans in my family and to all the veterans in yours.

November 8, 2013

Book Briefs

Roy Porter, The Enlightenment (Palgrave Macmillan, 2001). With 70 pages of text, this is meant to be a very brief introduction to the big ideas of the Enlightenment. Porter, one of the foremost experts on the time period, understands the Enlightenment “as precisely that point in European history when, benefiting from the rise of literacy, growing affluence, and the spread of publishing, the secular intelligentsia emerged as a relatively independent social force” (10). Unlike some of the older literature, Porter does not see the Englightenment in a “pitched battle against religion” (670), but he still presents the 18th century as largely vanquishing traditional religion.

Roy Porter, The Enlightenment (Palgrave Macmillan, 2001). With 70 pages of text, this is meant to be a very brief introduction to the big ideas of the Enlightenment. Porter, one of the foremost experts on the time period, understands the Enlightenment “as precisely that point in European history when, benefiting from the rise of literacy, growing affluence, and the spread of publishing, the secular intelligentsia emerged as a relatively independent social force” (10). Unlike some of the older literature, Porter does not see the Englightenment in a “pitched battle against religion” (670), but he still presents the 18th century as largely vanquishing traditional religion.

John Piper, Five Points: Towards a Deeper Experience of God’s Grace (Christian Focus 2013). My blurb: “As a child I grew up learning about the Five Points in my church and in my home. Now as a Reformed pastor I subscribe to them as part of our confessional standard. But, in the end, as important as family and tradition may be, the only truly legitimate reason for believing in the Doctrines of Grace is because they are found in the Bible. Which is why I love this new book by John Piper. I don’t know of any other brief book on this subject that so manifestly takes us down into the Scriptures and then so wonderfully lifts us up to see the glory of God. Many people will be encouraged, and not a few will have their faith jolted in the best way possible.”

John Piper, Five Points: Towards a Deeper Experience of God’s Grace (Christian Focus 2013). My blurb: “As a child I grew up learning about the Five Points in my church and in my home. Now as a Reformed pastor I subscribe to them as part of our confessional standard. But, in the end, as important as family and tradition may be, the only truly legitimate reason for believing in the Doctrines of Grace is because they are found in the Bible. Which is why I love this new book by John Piper. I don’t know of any other brief book on this subject that so manifestly takes us down into the Scriptures and then so wonderfully lifts us up to see the glory of God. Many people will be encouraged, and not a few will have their faith jolted in the best way possible.”

Gary Millar and Phil Campbell, Saving Eutychus: How to Preach God’s Word and Keep People Awake (Mathias Media, 2013). Easy to read, humorous, full of good reminders and some fresh suggestions too. I didn’t agree with every jot and tittle in the book—what preacher agrees with everything in someone else’s preaching book?—but I came away more aware of my weaknesses and with some new ideas to implement. Preachers will be helped by this book. Congregations should be pleased.

Gary Millar and Phil Campbell, Saving Eutychus: How to Preach God’s Word and Keep People Awake (Mathias Media, 2013). Easy to read, humorous, full of good reminders and some fresh suggestions too. I didn’t agree with every jot and tittle in the book—what preacher agrees with everything in someone else’s preaching book?—but I came away more aware of my weaknesses and with some new ideas to implement. Preachers will be helped by this book. Congregations should be pleased.

Charles R. Kesler, I Am the Change: Barack Obama and the Future of Liberalism (Broadside, 2012). Whether you like President Obama’s policies or not, this is a terrific book to get the conversation started. Kesler is a conservative and critical of Obama, but the Distinguished Professor from Claremont McKenna College has not written a slash and burn piece. In fact, as Kesler shows the antecedents of Obama’s policies in Woodrow Wilson, FDR, and LBJ, many liberals will nod in agreement. What’s more controversial is Kesler argument that progressivism asserts “the supremacy of public over private goods, of politics over economics, of statesmanship over the moneymaking arts” (47) and his critique of the movement for “this confusion of morality with history and this blindness to human nature and natural rights” (102).

Charles R. Kesler, I Am the Change: Barack Obama and the Future of Liberalism (Broadside, 2012). Whether you like President Obama’s policies or not, this is a terrific book to get the conversation started. Kesler is a conservative and critical of Obama, but the Distinguished Professor from Claremont McKenna College has not written a slash and burn piece. In fact, as Kesler shows the antecedents of Obama’s policies in Woodrow Wilson, FDR, and LBJ, many liberals will nod in agreement. What’s more controversial is Kesler argument that progressivism asserts “the supremacy of public over private goods, of politics over economics, of statesmanship over the moneymaking arts” (47) and his critique of the movement for “this confusion of morality with history and this blindness to human nature and natural rights” (102).

Elesha J. Coffman, The Christian Century and the Rise of the Protestant Mainline (Oxford University Press, 2013). This is a fascinating, well researched, and well crafted look at the rise (and fall) of the Mainline as exemplified in the rising (and mostly non-existent) fortunes of its leading periodical, The Christian Century. You’ll get from Coffman all the interesting bits about the inner workings of the Century, and how much they wanted to take down Billy Graham, and how nervous they were about the launching of Christianity Today. Here’s the money line from the book—which, incidentally, serves as a wise warning for any of us tempted to exaggerate our own influence: “The mainline amassed remarkable achievements, but reality could never quite match the movement’s confident rhetoric, largely because the resolutely forward-looking mainline leaders too seldom glanced over their shoulders to see if anyone was following them” (3).

Elesha J. Coffman, The Christian Century and the Rise of the Protestant Mainline (Oxford University Press, 2013). This is a fascinating, well researched, and well crafted look at the rise (and fall) of the Mainline as exemplified in the rising (and mostly non-existent) fortunes of its leading periodical, The Christian Century. You’ll get from Coffman all the interesting bits about the inner workings of the Century, and how much they wanted to take down Billy Graham, and how nervous they were about the launching of Christianity Today. Here’s the money line from the book—which, incidentally, serves as a wise warning for any of us tempted to exaggerate our own influence: “The mainline amassed remarkable achievements, but reality could never quite match the movement’s confident rhetoric, largely because the resolutely forward-looking mainline leaders too seldom glanced over their shoulders to see if anyone was following them” (3).

November 7, 2013

Is John Piper Really Reformed?

[image error]The answer to the question is obvious to most people, but often in two different directions.

For many people, John Piper is the most well known and most vigorous proponent of Reformed theology in the evangelical world today. He’s the guy who calls himself a seven point Calvinist. He exults in the sovereignty of God at every turn. He is, according to Mark Dever, “the single most potent factor in the recent rise of Reformed theology.” Of course, John Piper is Reformed.

But for others, it’s just as obvious that John Piper is not really Reformed. Reformed theology is defined by the Reformed confessions and finds its expression in Reformed and Presbyterian ecclesiastical structures, so clearly John Piper—as a credobapstist from the Baptist General Conference—is not Reformed. Why should “Reformed Baptist” sound any less strange than “Lutheran Baptist”?

I understand the point that those in the second category are trying to make. There is a real danger we equate Reformed theology with John Calvin and then equate John Calvin with TULIP, so that “Reformed” ends up meaning nothing more than a belief in predestination. Scholars like Richard Muller have worked hard to remind us that both equations are terribly reductionistic. Reformed churches existed before John Calvin, and Calvin’s thought was but one stream (a very important stream) flowing into and out of the Reformed tradition.

Likewise, anyone who has a deep appreciation for the Reformed confessions and has studied the development of Reformed theology will be understandably jealous to help people see that there is much more to being Reformed than a predestinarian soteriology. As one who subscribes to a historic Reformed denomination and has written a book on the Heidelberg Catechism, I am enthusiastic about all that the Reformed tradition has to offer, from ecclesiology, to worship, to our understanding of the law, to our understanding of the sacraments, to a dozen other things. I sympathize with those who are quick to point out that a college freshman who believes in a big God is not exactly plumbing the depths of what it means to be Reformed.

But on the other hand, it doesn’t bother me when John Piper is called Reformed. Besides the fact that he could likely affirm 95% of what is in the Three Forms and in the Westminster Standards—and I’m not suggesting the other 5% is inconsequential, I’m just making a point that the differences are not as great as one might think—I can readily acknowledge that the word “Reformed” is used in different ways. “Reformed” can refer to a confessional system or an ecclesiastical body. But “Reformed” or “Calvinist” can also be used more broadly as an adjective to describe a theology that owes much of its vigor and substance to Reformed theologians and classic Reformed theology.

Herman Bavinck’s chapter on the history of “Reformed Dogmatics” provides a good example. For starters, Bavinck notes how different Reformed theology is from Lutheran theology, the former being less tied to one country, less tied to one man, and less tied down in a single confession (Reformed Dogmatics, 1.177). Doctrinal development, Bavinck argues, has been richer and more multifaceted in Reformed theology (which may be one of the reasons you don’t hear of Lutheran Baptists).

In particular, Bavinck claims, “From the outset Reformed theology in North America displayed a variety of diverse forms.” He then goes on to mention the arrivals of the Episcopal Church (1607), the Dutch Reformed (1609), the Congregationalists (1620), the Quakers (1680), the Baptists (1639), the Methodists (1735 with Wesley and 1738 with Whitefield), and finally the German churches. “Almost all of these churches and currents in these churches,” Bavinck observes, “were of Calvinistic origin. Of all religious movements in America, Calvinism has been the most vigorous. It is not limited to one church or other, but—in a variety of modifications—constitutes the animating element in Congregational, Baptist, Presbyterian, Dutch Reformed, and German Reformed churches, and so forth” (1.201). In other words, not only is Bavinck comfortable using Calvinism has a synonym for Reformed theology (in this instance at least), he also has no problem affirming that Calvinism was not limited to one tradition alone but constituted the “animating element” in a variety of churches. Calvinism, as opposed to Lutheranism, flourished in colonial America as the typical orthodox, Reformational, sola scriptura-sola fide alternative to the various forms of comprised Arminianism and heterodox Socinianism.

The reason “Reformed” has not been confined in this country to those, and only those, who subscribe to the Three Forms or the Westminster Standards, is because from the beginning the basic contours of Calvinist theology pulsed through the veins of a variety of church bodies. Does this mean nothing but “the basic contours of Calvinist theology” matter for life and godliness? Certainly not—why else would Herman Bavinck go on to carefully delineate the intricacies of Reformed dogmatics for 2500 more pages. I am gladly Reformed, with a capital R as big as you can find.

Which is why my first reaction to the proliferation of even some of Reformed theology is profound gratitude. Do I think TULIP is the essence of Calvinism? No. Do I wish many who think of themselves as “Reformed” would go a lot farther back and dig a lot deeper down? Yes. But does it bother me that people think of Piper, Mohler, and Dever as Reformed? Not at all. They are celebrating and promoting Calvin and Hodge and Warfield and Bavinck and Berkhof—not to mention almost all of the rich Scriptural theology they expound—in ways that should make even the most truly Reformed truly happy.

November 5, 2013

10 Errors to Avoid When Talking about Sanctification and the Gospel

With lots of books and blog posts out there about law and gospel, about grace and effort, about the good news of this and the bad news of that, it’s clear that Christians are still wrestling with the doctrine of progressive sanctification. Can Christians do anything truly good? Can we please God? Should we try to? Is there a place for striving in the Christian life? Can God be disappointed with the Christian? Does the gospel make any demands? These are good questions that require a good deal of nuance and precision to answer well.

With lots of books and blog posts out there about law and gospel, about grace and effort, about the good news of this and the bad news of that, it’s clear that Christians are still wrestling with the doctrine of progressive sanctification. Can Christians do anything truly good? Can we please God? Should we try to? Is there a place for striving in the Christian life? Can God be disappointed with the Christian? Does the gospel make any demands? These are good questions that require a good deal of nuance and precision to answer well.

Thankfully, we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. The Reformed confessions and catechisms of the 16th and 17th centuries provide answers for all these questions. For those of us who subscribe to the Three Forms of Unity or to the Westminster Standards this means we are duty bound to affirm, teach, and defend what is taught in our confessional documents. For those outside these confessional traditions, there is still much wisdom you can gain in understanding what Christians have said about these matters over the centuries. And most importantly, these standards were self-consciously grounded in specific texts of Scripture. We can learn a lot from what these documents have to teach us from the Bible.

Sometimes the truth can be seen more clearly when we state its negation. So rather than stating what we should believe about sanctification, I’d like to explain what we should not believe or should not say. Each of these points is taken directly from one or more of the Reformed confessions or catechisms. Since I am more conversant I will stick with the Three Forms of Unity, but the same theology can be found just as easily in the Westminster Standards (see especially WCF Chapters 13, 16, 18, 19; LC Question and Answer 75-81, 97, 149-153; Shorter Catechism Question and Answer 35, 39, 82-87).

Error #1: The good we do can in some small way make us right with God. This is a denial of the gospel. The good we do is of no use to us in our justification because “even the very best we do in this life is imperfect and stained with sin” (HC Q/A 62). We “cannot do any work that is not defiled by our flesh and also worthy of punishment” (BC Art. 24).

Error #2: We must be good Christians so that God will keep loving us. To the contrary, the good news of justification by faith alone means that we can now “do a thing out of love for God” instead of “only out of love for [ourselves] and fear of being condemned” (BC Art. 24). In the midst of daily sins and weakness the struggling Christian should “flee for refuge to Christ crucified” (CD 5.2), truths that “it is not by their own merits or strength but by God’s undeserved mercy that they neither forfeit faith and grace nor remain in their downfalls to the end and are lost” (CD 5.8).

Error #3: If sanctification is a work of divine grace in our lives, then it must not involve our effort. We are absolutely “indebted to God for the good works we do” (BC Art. 24). He is the one at work in us both to will and to do according to his good pleasure. At the same time, “faith working through love” leads “a man to do by himself the works that God has commanded in his Word” (BC. Art. 24). Our ability to do good works “is not at all” in ourselves, but we still “ought to be diligent in stirring up the grace of God that is in [us]” (WCF 16.3).

Error #4: Warning people of judgment is law and has no part to play in preaching the gospel. Actually, “preaching the gospel” should both “open and close the kingdom of heaven.” The kingdom of heaven is opened by proclaiming to believers what God has done for us in Christ. The kingdom of heaven is closed by proclaiming “to unbelievers and hypocrites that, as long as they do not repent, the anger of God and eternal condemnation rest on them. God’s judgment, both in this life and in the life to come, is based on this gospel testimony” (HC Q/A 84).

Error #5: There is only one reason Christians should pursue sanctification and that’s because of our justification. The Heidelberg Catechism lists several reasons—motivations even—for doing good. “We do good because Christ by his Spirit is also renewing us to be like himself, so that in all our living we may show that we are thankful to God for all he has done for us, and so that he may be praised through us. And we do good so that we may be assured of our faith by its fruits, and so that by our godly living our neighbors may be won over to Christ” (HC Q/A 86).

Error #6: Since we cannot obey God’s commandments perfectly, we should not insist on obedience from ourselves or from others. While it is true that “in this life even the holiest have only a small beginning of this obedience,” that’s not the whole story. “Nevertheless, with all seriousness of purpose, they do begin to live according to all, not only some, of God’s commandments” (HC Q/A 114). Because we belong to Christ and our good works are “sanctified by his grace” (BC Art. 24), God “is pleased to accept and reward that which is sincere, although accompanied with many weaknesses and imperfections” (WCF 13.6).

Error #7: The Ten Commandments should be preached in order to remind us of our sin, but not so that believers may be stirred up to try to obey the commandments. The Heidelberg Catechism acknowledges that “no one in this life can obey the Ten Commandments perfectly,” but it still insists that “God wants them preached pointedly.” For two reason: “First, so that the longer we live the more we may come to know our sinfulness and the more eagerly look to Christ for forgiveness of sins and righteousness.” And “Second, so that, while praying to God for the grace of the Holy Spirit, we may never stop striving to be renewed more and more after God’s image, until after this life we reach our goal: perfection” (HC Q/A 115).

Error #8: Being fully justified as Christians, we should never fear displeasing God or offending him. The promise of divine preservation does not mean that true believers will never fall into serious sin (CD 5.4). Even believers can commit “monstrous sins” that “greatly offend God.” When we sin in such egregious ways, we “sometimes lose the awareness of grace for a time” until we repent and God’s fatherly face shines upon us again (5.5). God being for us in Christ in a legal and ultimate sense does not mean he will never frown upon our disobedience. But it does mean that God will always effectively renew us to repentance and bring us to “experience again the grace of reconciled God” (5.7).

Error #9: The only proper ground for assurance is in the promises of God found in the gospel. Assurance is not to be sought from private relation but from three sources: from faith in the promises of God, from the testimony of the Holy Spirit testifying to our spirits that we are children of God, and from “a serious and holy pursuit of a clear conscience and of good works” (CD 5.10). Assurance is not inimical to the pursuit of holiness, but intimately bound up with it. We walk in God’s ways “in order that by walking them [we] may maintain the assurance of [our] perseverance” (5.13). Personal holiness is not only a ground for assurance; the desire for assurance is itself a motivation unto holiness.

Error #10: Threats and exhortations belong to the terrors of the law and are not to be used as a motivation unto holiness. This is not the view of the Canons of Dort: “And, just as it has pleased God to begin this work of grace in us by the proclamation of the gospel, so he preserves, continues, and completes his work by the hearing and reading of the gospel, by meditation on it, by its exhortations, threats, and promises, and also by the use of the sacraments” (CD 5.14). Notice two things here. First, God causes us to persevere by several means. He makes promises to us, but he also threatens. He works by the hearing of the gospel and by the use of the sacraments. He has not bound himself to one method. Surely, this helps us make sense of the warnings in Hebrews and elsewhere in the New Testament. Threats and exhortations do not undermine perseverance; they help to complete it. Second, notice the broad way in which Dort understands the gospel (in this context). In being gospel-centered Christians, we meditate on the “exhortations, threats, and promises” of the gospel. In a strict sense we might say that the gospel is only the good news of how we can be saved. But in a wider sense, the gospel encompasses the whole story of salvation, which includes not only gospel promises but also the threats and exhortations inherent in the gospel.

Clearly, different sermons, different passages, and different problems call for different truths to be accented. One is not guilty of these errors simply by not saying everything that can be said. And yet, in the course of faithful preaching and teaching all the positive truths found in a robust, thoughtful doctrine of sanctification should be publicly declared. Likewise, although we may feel called to trumpet a certain truth about the gospel or sanctification—which certain times and certain texts call for—this in no way excuses the ten errors listed above. It is never wise to celebrate the truth by making statements that are false.

November 4, 2013

Monday Morning Humor

November 1, 2013

Moral Convictions Must Emerge Out in the Open

Some honest, thought provoking reflections from R. R. Reno on the pressure we face to deal politely with the erosion of moral truth:

A friend confides to me that he’s having an adulterous affair. I sigh inwardly over our sin-saturated condition as I remind him that the Ten Commandments are pretty clear about adultery. I counsel, but perhaps too sympathetically. I exhort, though often too gently. And even though he responds with self-justifying sophistries, it doesn’t affect our friendship very much. We go on as before, though maybe with a little more distance between us.

I have to a certain extent soft-pedaled moral truth because I’m weak and want to get along. Swimming against the current is exhausting and can be lonely. I reassure myself that at least I haven’t really condoned his transgression, haven’t affirmed as right that which is wrong. It’s an easy, thin, cowardly consolation, yes, but it’s also a crucial line of defense against the debilitating interior corruption of willingly and self-consciously betraying the truth.

Most of us who dissent from the sexual revolution do something similar, not just with friends but with society as a whole. We go to work socialize, and share public space with many people who reject the moral law’s authority over their lives, people who regard abortion as a fundamental right or who think sexual liberation an imperative. We do so in large part with civility and an appreciation for their good qualities. We accommodate ourselves to the moral realities of our time but don’t condone them. We do this because we can look away, not fixing on what is wrong because we are not forced to do so.

We can’t so easily accommodate when circumstances force the issue. If my married friend were to insist on bring his mistress to a dinner party, I’d be under tremendous social pressure to smile, shake her hand, and make her welcome, all of which would erode my defense against betraying the moral truth. I’ve done just that, or something similar. They are painful occasions. I feel myself bearing false witness, all but affirming out loud what I know to be wrong. As I struggle for moral survival, I try to reserve some moral space, deep within the privacy of my consciousness, where I’m saying “no” even as I’m socially saying “yes.”

In this and moments like it, I find myself wishing I prized politeness less and had the interior freedom to kick out my friend and his mistress—or in some way to give the moral truth that has been jammed into a far corner of my conscience some purchase on reality, some public expression. For a purely internal commitment, a moral conviction that never emerges out in the open when confronted by its negation, can easily, perhaps inevitably, become spectral, inconsequential, and eventually lifeless. (“Marriage Matters” in First Things, November 2013, p. 4)

October 31, 2013

The Glory of the Reformation: A Clean Conscience

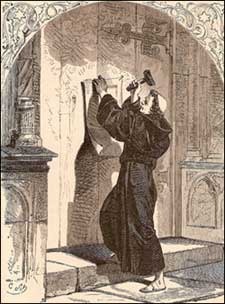

Reformation Day commemorates Martin Luther’s action in nailing the Ninety-Five Theses to the church door at Wittenberg on October 31, 1517.

Reformation Day commemorates Martin Luther’s action in nailing the Ninety-Five Theses to the church door at Wittenberg on October 31, 1517.

Just as consequential were the events that transpired a little over three years later.

In January 1521, Pope Leo X excommunicated Luther and called upon him to defend his beliefs before the Holy Roman Emperor at an Imperial Diet in Worms. When the Diet took place that April Luther, did not stroll into Worms a confident man. On the first day he was so intimidated his statements could hardly be understood. Luther had reason to be afraid, for there were plans to banish Luther from the empire (or worse) if he did not recant his books.

The interrogation was no short affair, but by the end Luther had summoned his courage, concluding with these famous words: “My conscience is captive to the Word of God. Thus I cannot and will not recant, for going against my conscience is neither safe nor salutary. I can do no other, here I stand, God help me. Amen.”

On May 26, 1521, the emperor rendered his decision. Luther was to be placed under “ban and double ban.” The Edict of Worms enjoined the men and women of the empire “not to take the aforementioned Martin Luther into your houses, not to receive him at court, to give him neither food nor drink, not to hide him, to afford him no help, following, support, or encouragement, either clandestinely or publicly, through words or works. Where you can get him, seize him and overpower him, you should capture him and send him to us under tightest security.”

Nevertheless Luther would live to see another day. . . .and another. . . .and another. . . .and another, managing escape from the imperial snare, sometimes quite dramatically. But Luther didn’t know any of that when he took his famous stand at Worms. What he did know was that he was willing to endure expulsion and face the gravest bodily harm for the sake of his conscience.

And not “conscience” as some liberated, self-directed, autonomous feeling. But conscience held “captive to the Word of God.” It’s not an exaggeration to say that the history of the Reformation, the history of Germany, the history of Europe, the history of the Church, and indeed the history of the world were changed because Martin Luther refused to do and say what he knew in his head and heart to be wrong.

As Christians, we don’t think about the significance of our consciences as much as we should. Of course, the conscience is not infallible. It can be evil (Heb. 10:22), seared (1 Tim. 4:2), defiled (Titus 1:15), or weak (1 Cor. 8:7). But that doesn’t allow us to ignore our conscience. There are more than a dozen occasions where the New Testament makes a positive reference to the testimony of the conscience.

For example:

Acts 23:1 “And looking intently at the council, Paul said, ‘Brothers, I have lived my life before God in all good conscience up to this day.’”

Romans 9:1 “I am speaking the truth in Christ-I am not lying; my conscience bears me witness in the Holy Spirit.”

2 Corinthians 1:12a “For our boast is this, the testimony of our conscience.

2 Timothy 1:3 “I thank God whom I serve, as did my ancestors, with a clear conscience.”

Hebrews 13:18 “Pray for us, for we are sure that we have a clear conscience, desiring to act honorably in all things.”

The conscience was not the final judge and jury in matters of the heart, but it is one of the most important witnesses to bring to the stand. Conscience-as the faculty within human beings that assesses what is right and what is wrong-is meant to be, as the Puritans put it, “God’s spy and man’s overseer.” It is our prosecuting attorney, bringing up offenses and producing guilty. And just as importantly, the conscience is our defense attorney, helping us face false accusations and slanders of the evil one (Rom. 2:14-15).

Having a conscience is a mark of being a sentient adult, as one (to use scriptural langauge) who knows his right hand from his left. The conscience is what separates us from the animals, which is why Pinocchio becomes a beast when he ignores his conscience and persists in deceit. Conscience is indispensable to being a human being that lives the good life, enjoys peace with God, and lives a life pleasing to God.

In a day where we are encouraged to do whatever feels good, in a day where a moral compass is thought to be prudish and narrow, in a day where the state thinks nothing of trampling on the liberty of consciences, we would do well to remember Luther’s example and remember what the Bible says.

Acts 24:16 “So I always take pains to have a clear conscience toward both God and man.”

1 Tim. 1:5 “The aim of our charge is love that issues from a pure heart and a good conscience and a sincere faith.”

1 Peter 3:16 – “Have a good conscience so that when you are slandered those who revile your good behavior in Christ may be put to shame.”

If you are caught in sin and your conscience accuses you, turn from iniquity. If you are smitten with regret for past mistakes and offenses, run to the cross. And if you are faced with the choice to follow the world or obey your conscience, pray for the same courage that descended upon Luther at Worms.

“Conscience is either the greatest friend,” Richard Sibbes once remarked, “or the greatest enemy in the world.” Don’t ignore his wisdom. There is no friend like a clean conscience and no enemy like a conscience doing its God-given work. Turn from sin and turn to Christ. Stand your ground. Get on your knees. Be a captive to the Word of God and boast in your conscience.

October 30, 2013

How To Have An Abortion

The latest issue of First Things (November 2013) contains a poem from Bryce A. Taylor entitled “How to Have an Abortion.” I found it startling, poignant, and moving.

Don’t think about the freckles he, or she,

Might have, or how much hair, how big a grin,

Or whether swimming would come naturally,

Or whether–it?–might play the violin.

Don’t think of prom, don’t think of puppy love

Or calculus, or snow, or spring in bloom,

Or anything that might remind you of

The future now contained within a womb.

Don’t feel anxiety, don’t feel regret,

Don’t fret about some otherworldly guilt.

Don’t feel the bond of parenthood, don’t let

Insane outmoded Don Quixotes tilt

At private windmills–don’t spill any ink

Examining yourself. Don’t feel. Don’t think.

As you should with all good poems, read this one through slowly, and a few more times.

October 29, 2013

The Sufficiency of Christ and the Sufficiency of Scripture

The big idea in Hebrews 1 is the point of all of Hebrews: The Son is superior to all others because in him we have the fullness and finality of God’s redemption and revelation.

We do pretty well understanding the fullness piece. Everything in the days “long ago” was pointing to Christ, and everything was completed in Christ. He is the fulfillment of centuries of predications, prophecies, and types. That’s the fullness part of the equation.

But just as important is the finality of Christ’s work. God has definitively made himself known. Christ has once for all paid for our sins. He came to earth, lived among us, died on the cross, and cried out in the dying moments, “It is finished!” We are awaiting no other king to rule over us. We need no other prophet like Mohammed. There can be no further priest to atone for our sins. The work of redemption has been completed.

And we must not separate redemption from revelation. Both were finished and fulfilled in the Son. The word of God versus the Word of God, the Bible versus Jesus, the Scriptures versus the Son—Hebrews gives no room for these diabolical antitheses. True, the Bible is not Jesus; the Scripture is not the Son. The words of the Bible and the Word made flesh are distinct, but they are also inseparable. Every act of redemption—from the Exodus, to the return from exile, to the cross itself—is also a revelation. They tell us something about the nature of sin, the way of salvation, and the character of God. Likewise, the point of revelation is always to redeem. The words of the prophets and the apostles are not meant to make us smart, but to get us saved. Redemption reveals. Revelation redeems.

And Christ is both. He is God’s full and final act of redemption and God’s full and final revelation of himself. Even the later teachings of the apostles were simply the remembrances of what Christ said (John 14:26) and the further Spirit-wrought explanation of all that he was and all that he accomplished (John 16:13-15). “Nothing can be added to his redemptive work,” Frame argues, “and nothing can be added to the revelation of that redemptive work.”[1] If we say revelation is not complete, we must admit that somehow the work of redemption also remains unfinished.

A Silent God?

Does this mean God no longer speaks? Not all. But we must think carefully about how he speaks in these last days. God now speaks through his Son. Think about the three offices of Christ—prophet, priest, and king. In the tension of the already and not yet, Christ has finished his work in each office. And yet, he continues to work through that finished work.

As a king, Christ is already seated on the throne and already reigns from heaven, but the inauguration of his kingdom is not the same as the consummation of it. There are still enemies to subdue under his feet (Heb. 2:8).

As a priest, Christ has fully paid for all our sins with precious blood, once for all, never to be repeated again. And yet, this great salvation must still be freely offered and Christ must keep us in it (Heb. 2:3).

Finally, as a prophet, God has decisively spoken in his Son. He has shown us all we need to know, believe, and do. There is nothing more to say. And yet, God keeps speaking through what he has already said. The word of God is living and active (Heb. 4:12), and when the Scriptures are read the Holy Spirit still speaks (Heb. 3:7).

So, yes, God still speaks. He is not silent. He communicates with us personally and directly. But this ongoing speech is not ongoing revelation. “The Holy Spirit no longer reveals any new doctrines but takes everything from Christ (John 16:14),” Bavinck writes. “In Christ God’s revelation has been completed.”[2] In these last days, God speaks to us not by many and various ways, but in one way, through his Son. And he speaks through his Son by the revelation of the Son’s redeeming work that we find first predicted and prefigured in the Old Testament, then recorded in the gospels, and finally unpacked by the Spirit through the apostles in the rest of the New Testament.

Scripture is enough because the work of Christ is enough. They stand or fall together. The Son’s redemption and the Son’s revelation must both be sufficient. And as such, there is nothing more to be done and nothing more to be known for our salvation and for our Christian walk than what we see and know about Christ and through Christ in his Spirit’s book. Frame is right: “Scripture is God’s testimony to the redemption he has accomplished for us. Once that redemption is finished, and the apostolic testimony to it is finished, the Scriptures are complete, and we should expect no more additions to them.”[3] While God certainly illumines his word and may impress upon us direct applications from his word, he does not speak apart from the word. Or as Packer puts it, more tersely but no less truly, “There are no words of God spoken to us at all today except the words of Scripture.”[4]

[1] Frame, The Doctrine of the Word of God, 227.

[2] Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, Volume 1: Prolegomena, gen ed. John Bolt, tr. John Vriend (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003), 491.

[3] Frame, The Doctrine of the Word of God, 227.

[4] Packer, “Fundamentalism” and the Word of God, 119.