Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 190

January 14, 2011

A Secret to Calvin's Success (and Ours)

A couple weeks ago I urged churches to give their pastors adequate vacation time. Not at all opposed to that piece of advice, I now want to urge pastors (and everybody else for that matter) to work extremely hard. Both are true: God wired us for rest and he made us to work.

A couple weeks ago I urged churches to give their pastors adequate vacation time. Not at all opposed to that piece of advice, I now want to urge pastors (and everybody else for that matter) to work extremely hard. Both are true: God wired us for rest and he made us to work.

Ministry is hard work and those engaged in it (whether vocationally or not) should work at it hard. Paul "worked harder than any of them," though he quickly added, "not I, but the grace of God that is with me" (1 Cor. 15:10). And for all the dead tired missionaries, pastors, moms, dads. teachers, chaplains, elders, and deacons out there–to all who in some measure care for the lives of others–let us say with the Apostle, "I will most gladly spend and be spent for your souls" (2 Cor. 12:15). Every Christian serves, and every Christian who serves well works hard to serve.

Like John Calvin.

I've been slowly working my way through Bruce Gordon's masterful biography of the Genevan Reformer (Yale 2009). Recently I underlined this passage:

And here was a formula that would serve Calvin well throughout his time in the city: extremely hard work on his part combined with the disorganization and failings of his opponents. (133)

No doubt, Luther and Calvin and Owen and Edwards and name-your-hero were brilliant. But they also were indefatigable. They did so much, in part, because God gave them the discipline, the drive, and the single-minded determination to keep their hands to the plow more than almost anyone else.

The combination of teaching, preaching, writing and pastoral care was doubtless exhausting, but was the routine familiar to all sixteenth-century reformers. Melanchthon in Wittenberg, Bullinger in Zurich and Bucer himself in Strasbourg knew nothing other than long days of labour and service that began with early-morning worship and ended with writing and reading texts and letters by candlelight. It was how they had been educated from boyhood, and many had monastic backgrounds. The extraordinary discipline and single-mindedness of the reformers becomes apparent only when we stop to consider how much they achieved. (86)

Take a day off each week. Enjoy your vacations (I just did). If you are in a profession that affords a sabbatical, make the most of it. But never forget we were made to work, be it prayer, writing, teaching, computing, changing bed pans, or swinging a hammer. Whatever good is accomplished in and through the church will be by the grace of God. And normally that grace will flow most (thought not necessarily most noticeably) through those whom God enables to work the hardest.

January 13, 2011

Grace Abounding to Sinners or Erasing Ethnic Boundaries?

This is the title to the last chapter of Stephen Westerholm's terrific book Perspectives Old and New on Paul: The "Lutheran" Paul and His Critics (Eerdmans 2004). Evangelical and reformed types concerned with the New Perspective(s) on Paul have rightly turned to John Piper, D.A. Carson, Tom Schreiner, and Guy Waters for help. But too few, I would guess, have looked to Stephen Westerholm. They should. I have only a few books by Westerholm and have not yet finished this one, but I like what I've read before and what I'm reading now.

The "Whimsical Introduction" where Martin Luther reads Sanders, Dunn, and Wright is ingenious and (surprisingly for a serious scholar) actually quite whimsical. In Part One, Westherholm examines Paul and justification through his classic interpreters: Augustine, Luther, Calvin, and Wesley. Despite their differences in theology, these four expositors produced a remarkably similar "Lutheran" Paul and a consistent doctrine of justification. In Part Two, he explores the twentieth-century responses to the "Lutheran" Paul. In Part Three, Westerholm looks at the Pauline texts for himself to demonstrate that the "Lutheran" Paul might not be too far off from the real Paul.

Which brings us to the title of this post and the last chapter of the book. While Westerholm admits that "the alternatives of our title are falsely put" he is trying to make an important point (440). One of the key issues, if not the issue, that divides the "Lutheran" Paul from his new critics is "whether 'justification by faith, not by works of the law" means 'Sinners find God's approval by grace, through faith, not by anything they do,' or whether its thrust is that 'Gentiles are included in the people of God by faith without the bother of becoming Jews'" (445). This fairly gets at the crux of the matter. Was Paul's doctrine of justification about being right with God by faith alone or was it about the abrogation of food laws, special rites, and special days?

Of course, in one sense, as Westerholm points out, justification was clearly about both and we must do justice to both. But doing justice to both does not mean we let historical reconstruction rob God's people of theological gold and pastoral comfort.

As I see things, the critics have rightly defined the occasion that elicited the formulation of Paul's doctrine and have reminded us of its first-century social and strategic significance; the "Lutherans," for their part, rightly captured Paul's rationale and basic point. For those (like Augustine, Luther, Calvin, and Wesley) bent on applying Paul's words to contemporary situations, it is the point rather than the historical occasion of the formulation that is crucial (445).

In other words, let us say thank you to the New Perspective for reminding us that great doctrine of justification was, for Paul, tied up in the nitty-gritty of diet, foreskins, ethnic tensions, and the history and purpose of Israel. But let us never forget that all of this gave rise to the bold proclamation of the precious news that "by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast" (Eph. 2:8-9).

So yes, justification by faith resulted in the "erasing of ethnic boundaries." But Augustine, Luther, Calvin, Wesley and every faithful gospel preacher before and after them have also been right to preach the good news of "grace abounding to sinners." This is the heartbeat, the tap root, and basic point of justification by faith. And if this happens to be "Lutheran" that's ok, because it happens to be biblical too.

January 12, 2011

What's the Message of the Bible in One Sentence?

Twenty-five pastors and scholars answer the question here.

The different approaches and emphases are enlightening. And the question itself, though impossible to answer, does present a good challenge to summarize the biblical message with simplicity and brevity.

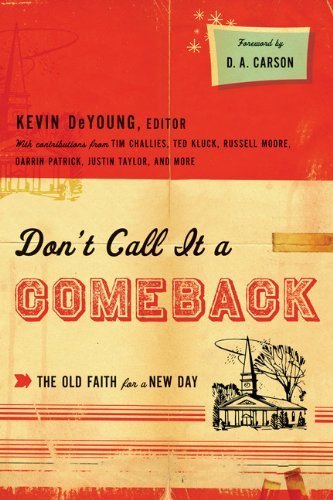

Don't Call It a Comeback: Interviews, Part 1

Don't Call It a Comeback: The Same Evangelical Faith for a New Day is set to be released on January 31st. I've been working on this project in one way or another for the past 18 months. Along the way I've become convinced of two things: 1) being an editor is more work than writing a book, and 2) there are a lot of great, young church leaders out there. It was fun to work with these men over the past year. Our hope is that this project can help reassert the wonder, the relevance, and the necessity of theological and ethical orthodoxy for a new generation.

Don't Call It a Comeback: The Same Evangelical Faith for a New Day is set to be released on January 31st. I've been working on this project in one way or another for the past 18 months. Along the way I've become convinced of two things: 1) being an editor is more work than writing a book, and 2) there are a lot of great, young church leaders out there. It was fun to work with these men over the past year. Our hope is that this project can help reassert the wonder, the relevance, and the necessity of theological and ethical orthodoxy for a new generation.

Over the next four Wednesdays I'll introduce the contributors and ask them a specific question related to their chapter. Today we have Hansen, Leeman, Naselli, and Gilbert.

Collin Hansen, editorial director, The Gospel Coalition. Collin is married to Lauren. His chapter is "The Story of Evangelicalism from the Beginning and Before."

What is one of the most important things many evangelicals don't know about their own history?

I'm afraid that many evangelicals don't know that their history is about God. We so often tell our history as a succession of famous leaders, writers, councils, and battles over doctrine. I do a lot of that in my chapter for Don't Call It a Comeback. And to some degree it's true: God has worked through great leaders, books, and councils to preserve his church and proclaim the gospel of Jesus Christ.

But I fear that this way of telling the story leads us to draw the wrong conclusions for our own day. We think if we can just get our doctrine right and honor the right leaders, then God will bless us with tremendous church growth. But as I researched A God-Sized Vision: Revival Stories That Stretch and Stir, I learned that's not what history looks like. The most gifted, faithful Christians may toil in obscurity. God uses leaders with mixed motives to accomplish his purposes. And just when all hope seems lost, God sometimes revives his church with a tremendous outpouring of his presence through the Holy Spirit. This way God reminds us that history is about him, his story of salvation from first to last.

Jonathan Leeman, director of communications, 9Marks (Washington, DC). Jonathan is married to Shannon and they have three daughters. His chapter is entitled, "God: Not Like You."

Your chapter is about the doctrine of God and how he is different than his creatures. Why is it good news that God is not like us?

Here are four reasons:

1) Moses told Pharaoh that "no one is like the LORD our God" (Ex. 8:10) because God's plans cannot be thwarted. That's good news because none of the God-opposing forces which you and I watch on movie screens or read about in newspapers will keep Christ from fulfilling his final victory.

2) David praised God saying "there is none like you" (2 Sam. 7:22) because God shakes up entire nations to redeem his people, all the while accounting for puny individuals like David by name. That's good news because our God includes insignificant us in his grand plans for the universe.

3) Solomon also praises God with the words "there is no God like you" (1 Kings 8:23) because God alone is faithful to his Word. That's good news because we can rely on his promises.

4) Finally, God himself tells us, "I am God, and there is none like me" (Is. 46:9) because he rules over eternity and has ordained the end from the beginning. That's good news because it means that, through all the ups and downs of life, the end is certain and—for those who love him and are called according to his purpose—the end is good.

Andrew David Naselli, Research Manager for D. A. Carson and Administrator of Themelios (Moore, South Carolina). Andy is married to Jenni, and they have two children. He writes the fourth chapter, "Scripture: How the Bible is a Book Like No Other."

What do you see as the biggest threat to the authority of the Scriptures among evangelicals today?

One of the most serious threats is treating the Bible as merely an authority. That is, it is one of many authorities but not the final, ultimate, supreme authority. Reducing the Bible's authority like that is common in the fields of science and history, and it's becoming common in other fields. For example, people may arrive at their theology by giving equal or greater weight to the latest psychological studies, self-help philosophies, or talk-radio opinions. The result is syncretism.

The Protestant Reformers rightly defended sola Scriptura. This doesn't mean that Scripture is the only source of any truth in the world. It means that Scripture is the only inerrant and infallible authority. It is the final authority for every domain of knowledge it addresses. It's supremely authoritative. It's like no other book.

Greg Gilbert, Senior Pastor, Third Avenue Baptist Church, Louisville, KY. He is married to Moriah. They have three children: Justin, Jack and Juliet. His chapter, not surprisingly, is on the gospel, "The Gospel: God's Self-Substitution for Sinners."

You argue that the heart of the gospel is God's self-substitution for sinners. Why do you think there is hostility in some quarters to this understanding of the gospel?

I think it must be, finally, because of the very thing Paul said in 1 Corinthians: The message of the cross is always going to be thought by most of the world to be utter foolishness. If you think about it, the gospel of salvation through Jesus cuts against everything we as human beings naturally want to think about ourselves, and about God. We want to think of ourselves as basically good; the gospel tells us we are basically sinful. We want to think we are capable of saving ourselves; the gospel says we are wholly incapable of doing that. We want to think about God as one who forgives but never judges; the gospel tells us that he is so righteous that saving sinners required him to kill his Son.

Now, if you take all that offense that the world feels against the message of the cross, and mix it up with a usually good desire among Christians to make the gospel winsome and attractive to the world, you wind up with a very strong incentive—if you're not enormously cautious—to leave out or soften the things about the gospel that the world finds most offensive. You begin to shift the center of the gospel away from the cross and onto happier things, in order to help people hear it with less offense. And when that begins to happen, it's not surprising in the least that one of the first things to go—to get left out or softened beyond recognition and offense—is the offensive message of God's self-substitution for sinners.

January 11, 2011

The Tucson Tragedy and God's Gift of Moral Language

On Saturday a young man opened fire outside a Safeway grocery store in Tuscon, Arizona, killing six people, a 9-year old girl among them, and wounding 14 others, including Arizona Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords. This is a tragedy. Twenty persons made in the image of God with a right to life and liberty have been killed or wounded by the attack. May God grant healing to those whose lives can still be saved and comfort to all those mourning their dead.

Most of you know all this already. And most of you know all about the political jabs going back and forth whether this attack was made more likely because of a "climate of hate" (to use Paul Krugman's phrase describing the rhetoric of the right) or whether those who posit such theories (like Krugman on the left) are themselves the indecent ones. Personally I think Ross Douthat's op-ed piece in the New York Times gets it just about right: "Chances are that [Jared] Loughner's motives will prove as irreducibly complex as those of most of his predecessors in assassination." And later, "There is no faction in American politics that actually wants its opponents dead."Thankfully this is true.

But I noticed in Douthat's article what I notice in every other write-up on the shooting: a reflexive reluctance to speak of the killer's inner workings–his motivations, his make-up, his soul if you will–with moral categories. Douthat does better than most in speaking of Loughner's "darkness," but even here there is the subtle us of passive imagery. "Politicians and media loudmouths," Douthat writes, "shouldn't be held responsible for the darkness that always waits to swallow up the unstable and the lost." True enough, but who should be held responsible? My vote is for Loughner who, by all accounts, appears to be not only the accused killer but also the real killer. Certainly darkness is appropriate imagery, but I'd argue it's more appropriate to say he committed a dark deed rather than to imply darkness swallowed up an unstable young man.

A Predictable Pattern

I remember the same thing happening with the Virginia Tech massacre in 2007. Dr. Richard Roberts of Oral Roberts University said the act was Satanic in origin, though he was unsure if it was demonic oppression or possession. Rabbi Peter Rubenstein suggested that Seung-Cho Hui lost contact with the good inclination within him. Psychologist Philip Zimbardo explained that "normal" individuals can be trapped in emotional prisons that create aberrant and evil behavior. Robert Schuller concluded, "it's pure psychotic crack-up." Thankfully Richard Lints from Gordon-Conwell provided the last quote in the same article. "The lesson," he said, "is that when we don't take our own evil seriously, we are much more liable to perpetrate acts of evil." At least someone said the "e" word.

I have no doubt Loughner is messed up, crazy, off his rocker, and out to lunch. It seems that he's needed help for a long time. By why jump to conclude that this is a "Tragedy of Mental Illness"? To be sure, mental illness is real but it does not honor those who endure it to rush a diagnosis and start naming disorders every time an anti-social, nihilistic, solipsistic young man with guns and grudges sins in the worst possible ways. Where have all the active verbs gone?

Words Have Meaning

Unfortunately, pundits shy away from explicitly personal and moral categories in the precisely the moments we need them most (9-11 may be the one exception). Whenever a public tragedy like this occurs everyone on the right and the left struggles to find some cause, and that cause is almost always outside the self—video games, strange novels, mistreatment by friends, a culture of hate, the second amendment, heated political rhetoric. And when an internal cause is suggested it almost always points away from personal responsibility to some element of us that doesn't really belonging to us—like a mental disorder or our own personal demons.

We instinctively resort to passive speech, unable to bear the thought (let alone utter the words) that a wicked person has perpetrated a wicked crime. The human heart is desperately sinful and capable of despicable sins. Of course, no one commends the crime, but few are willing to condemn the criminal either. In such a world we are no longer moral beings with the propensity for great acts of righteousness and great acts of evil. We are instead, at least when we are bad, the mere product of our circumstances, our society, our upbringing, our biochemistry, or our hurts. The triumph of the therapeutic is nearly complete.

Losing Our Religion, And Evil Too

We are so awash in the language of disorders and dysfunction that we don't know how to talk about good and evil. There was a book published in 1995 called The Death of Satan: How Americans Have Lost Their Sense of Evil by Andrew Delbanco. The opening paragraphs are worth reading carefully.

A gulf has opened up in our culture between the visibility of evil and the intellectual resources available for coping with it. Never before have images of horror been so widely disseminated and so appalling–from organized death camps to children starving in famines that might have been averted. Rarely does a week go by without newspaper and television accounts of teenagers performing contract killings for a few dollars, women murdered on the street for their purses or their furs, young men shot in the head for the keys to their jeep–and these are only the domestic bulletins…

The repertoire of evil has never been richer. Yet never have our responses been so weak. We have no language for connecting our inner lives with the horrors that pass before our eyes in the outer world…

In our disenchanted world, one respected historian has recently remarked (and here he is perfectly representative) that mass murderers like Hitler and Stalin require us "judiciously [to] distinguish mental disorders that incapacitate from streaks of disorder that should not diminish responsibility." This distinction would be meaningless to the scores of millions who died at their hands. What does it mean to say that inventor of the concentration camps, or of the Gulag, was subject to a "disorder?" What does it mean to call these monsters mentally disordered, and to engage in scholastic debate over whether their brand of madness vitiates their responsibility? Why can we no longer call them evil? (3-4).

Delbanco finishes the book by saying "My driving motive in writing [this book] has been the conviction that if evil, with all the insidious complexity which Augustine attributed to it, escapes the reach of our imagination, it will have established dominion over us all" (234). Chilling and true.

The world, and to a large extent the church, has lost the ability to speak in moral categories. We have preferences instead of character. We have values instead of virtue. We have no God of holiness, and we have no Satan. We have break-downs, crack-ups, psychoses, maladjustments, and inner turmoil. But we do not have repugnant evil as the Bible has it. And this loss makes the world a more dangerous place. For the words may disappear, but the reality does not.

January 10, 2011

Monday Morning Humor

Well, I enjoyed a nice week at home with the family. One of the new Christmas toys for the kids (ahem, for the kids of course) was the old Super Mario Bros. game that can be downloaded to your Wii. Brought back a lot of memories, including this video from a talent show at my wife's alma mater.

And who says college students don't have any free time?

January 7, 2011

Ryle: Pastoral Reflections on Sanctification

What should we do with this teaching on sanctification? How does it matter for the average Christian? Ryle's thoughts:

For one thing, let us awake to a sense of the perilous state of many professing Christians.

For another thing, let us make sure work of our own condition, and never rest till we feel and know that we are "sanctified" ourselves.

For another thing, if we would be sanctified, our course is clear and plain—we must begin with Christ.

For another thing, if we would grow in holiness and become more sanctified, we must continually go on as we began, and be ever making fresh applications to Christ.

For another thing, let us not expect too much from our own hearts here below.

Finally, let us never be ashamed of making much of sanctification, and contending for a high standard of holiness. (pg. 39-40)

Personally, I think all six of these points need more emphasis today, even the ones that seem contradictory like 2 and 5. We need more passion for holiness, more effort toward holiness, and more of a realization that the growth is slow, spotty, and at times downright disappointing. But in Christ, we can grow into the person he has already reckoned us to be.

January 6, 2011

Ryle: Justification and Sanctification

Is there any theological distinction more important than the difference between justification and sanctification. Both are necessary for the Christian, but they are not the same. Similar, but different.

So how are justification and sanctification alike?

Both proceed originally from the free grace of God. It is of His gift alone that believers are justified or sanctified at all.

Both are part of that great work of salvation which Christ, in the eternal covenant, has undertaken on behalf of His people. Christ is the fountain of life from which pardon and holiness both flow. The root of each is Christ.

Both are to be found in the same persons. Those who are justified are always sanctified, and those who are sanctified are always justified. God has joined them together, and they cannot be put asunder.

Both begin at the same time. The moment a person begins to be a justified person, he also begins to be a sanctified person. He may not feel it, but it is a fact.

Both are alike necessary to salvation. No one ever reached heaven without a renewed heart as well as forgiveness, without the Spirit's grace as well as the blood of Christ, without a meetness for eternal glory as well as a title. The one is just as necessary as the other.

But we must also recognize how the two are profoundly different (and remember, Ryle is talking about sanctification as a theological concept, that positional sanctification as the NT often used the term).

Justification is the reckoning and counting a man to be righteous for the sake of another, even Jesus Christ the Lord. Sanctification is the actual making a man inwardly righteous, though it may be in a very feeble degree.

The righteousness we have by our justification is not our own, but the everlasting perfect righteousness of our great Mediator Christ, imputed to us, and made our own by faith. The righteousness we have by sanctification is our own righteousness, imparted, inherent, and wrought in us by the Holy Spirit, but mingles with much infirmity and imperfection.

In justification our own works have no place at all, and simple faith in Christ is the one thing needful. In sanctification our own works are of vast importance, and God bids us fight, and watch, and pray, and strive, and take pains, and labour.

Justification is a finished and complete work, and a man is perfectly justified the moment he believes. Sanctification is an imperfect work, comparatively, and will never be perfected until we reach heaven.

Justification admits of no growth or increase: a man is as much justified the hour he first comes to Christ by faith as he will be to all eternity. Sanctification is eminently a progressive work, and admits of continual growth and enlargement so long as a man lives.

Justification has special reference to our persons, our standing in God's sight, and our deliverance from guilt. Sanctification has special reference to our natures, and the moral renewal of our hearts.

Justification gives us our title to heaven, and boldness to enter in. Sanctification give us our meetness for heaven, and prepares us to enjoy it when we dwell there.

Justification is the act of God about us, and is not easily discerned by others. Sanctification is the work of God within us, and cannot be hid in its outward manifestation from the eyes of men.

Tomorrow: I'll wrap up the chapter summary with Ryle's pastoral reflections.

January 5, 2011

Homeless Man Gets Clean, Gets a Second Chance

This is a great story.

Ted Williams (not the ball player) had a promising life, that is until he seemed to have ruined it with drugs and alcohol. Now he's says God's given him a second chance. He's been clean for two years and is looking for work.

So what does a homeless man and recovering addict do to get back on his feet?

Well, this man has already been offered a position by the Cleveland Cavaliers. He will be on the Today show on Thursday and NFL Films says they will be contacting him too.

Watch this video to find out why. Pretty amazing.

"I can't believe what's going on. God gave me a million-dollar voice, and I just hope I can do right by him," the 53-year old Williams remarked. "I just hope everyone will pray for me." Good idea for him and for us.

Read more from the Chicago Tribune or ESPN.

Ryle: The Visible Signs of Sanctification

What does holiness look like? J.C. Ryle explains:

True sanctification then does not consist in talk about religion.

True sanctification does not consist in temporary religious feelings.

True sanctification does not consist in outward formalism and external devoutness.

Sanctification does not consist in retirement from our place in life, and the renunciation of our social duties.

Sanctification does not consist in the occasional performance of right actions. (p. 32)

Genuine sanctification will show itself in habitual respect to God's law, and habitual effort to live in obedience to it as the rule of life.

Genuine sanctification will show itself in an habitual endeavour to do Christ's will, and to live by His practical precepts.

Genuine sanctification will show itself in an habitual desire to live up to the standard which St. Paul sets before the churches in his writings.

Genuine sanctification will show itself in habitual attention to the active graces which our Lord so beautifully exemplified, and especially to the grace of charity.

Genuine sanctification, in the last place, will show itself in habitual attention to the passive graces of Christianity.

This list would make a good tool for self-examination and a good prompt for prayer. Ryle's signs are biblical, and easier to understand that Jonathan Edwards.

Tomorrow: how justification and sanctification are alike and different.