Kevin DeYoung's Blog, page 133

July 26, 2012

From Metro to Retro – Part 3 of 4

[image error]GUEST POST: Josh Blunt

As I intimated in my last post, the journey through a decade of church planting led my congregation and me to reconsider our early bias toward an attractional, seeker-driven model. I also indicated that this reconsideration led us into an ordinary means of grace paradigm, focused on unadorned, expository preaching, regular celebration of the sacraments, and prayer, as well as the marks of the true Church.

This shift, occurring in the middle of my tenure, caused some radical changes in our life together as a congregation. What ensued was not a panacea of blissful fellowship and peace. It was, rather, a period of uprooting and refining that began with bold, unapologetic proclamation of God’s Word. The remarkable thing was how quickly this first shift began to tear the fabric of our fellowship and complicate our life together.

To explain this, I should mention that we planted in a locale already dominated by our own denominational brand. We felt we would still be fruitful, since we were ministering in a way that was sufficiently different from other churches in our tradition (contemporary and attractional), and because we were reaching the unchurched. What we ended up with, however, was an equal mix of three groups: A) religious people from our tradition, B) formerly religious people from other traditions, and C) formerly irreligious people who converted through our ministry.

The strategic strength (and ecclesiological weakness) of the attractional model was that all three groups heard winsome positives that seemingly affirmed their preferences. Simultaneously, no group felt confronted with unpleasant limits or boundaries that would offend them or challenge their presuppositions. In effect, the attractional model allowed us to be fuzzy enough to draw people with a wide variety of spiritual agendas, each one fully expecting that the new congregation would progress into exactly the kind of church he preferred.

In other words, we were a ticking time bomb of agenda disharmony. One of the ways this attractional ambiguity most crippled us was in the basic elements of our life together. Our discipleship of new believers, our prayer culture, and our common understanding of the sacraments had been too anemic in the attractional years, and had failed to bring true unity. We had intended to “major in the majors and minor in the minors,” but instead had merely “agreed on the agreeables and avoided the avoidables.”

Discipleship was our greatest weakness. In our zeal to attract and retain, we never made time for simple, repeatable, biblical formation of each person’s faith and practice. The highly religious remained content in their pharisaism, the formerly religious struggled to articulate their newfound convictions, and the formerly irreligious were hungry but helpless without mature mentors. Our efforts to convert existing small groups into more disciple-producing formats sparked conflict because they chafed against the “fun-and-fellowship-only” bias some had. In other words, not all of us wanted to grow (at least not in front of one another) and attractional church had somehow legitimized that option.

Similarly, our efforts to pray together struggled to get off the ground. The attractional model had kept us busy baiting the Sunday morning hook, and very few felt convicted that prayer was the real work of ministry. We had a committed prayer team who were faithful to invite others, but our disinclination toward longer intercessions in public worship and our weak discipleship habits gave newer converts little opportunity to observe or be formed by public prayer before joining the conversation. As we peppered more prayer on all levels of life together, there was pushback from some who felt exposed or stretched into discomfort that hadn’t been advertised in our attractional days.

Finally, our understanding of the sacraments evolved, as well. We adopted a more frequent, reverent, and liturgically consistent celebration of the Lord’s Supper. We also grew more bold in our defense of our denomination’s paedobaptist theology. Attractional thinking had led us to soft sell our position and welcome those who espoused believer baptism. This tolerance was still affirmed; however, we began to realize we had worked so hard at honoring the exception that we had failed to champion the rule. As we deepened in our understanding of the sacraments, we realized that our membership classes had inadequately trained our people to articulate a robust appreciation for these important means of grace.

As these changes continued to expose previously unchallenged assumptions and differing preferences, we began to experience and struggle with “unmentionables.” In my final post, I will share how unresolved conflict, issues of church discipline, and clarifications about gender roles all became important in our journey and further highlighted the ways in which being attractional had left us less governable and sustainable in the end.

July 25, 2012

From Metro to Retro (2 of 4)

GUEST POST: Josh Blunt

GUEST POST: Josh Blunt

As a church planter in the early part of this century, I had been trained well at seminary to offer a workmanlike (here read, “including explicit indication that original languages had been thoroughly exegeted”) and pleasing (here read, “relatively short in length, delightfully delivered, and winsome in tone”) message each Sunday. I had been educated in all the nuances and catchphrases that would help me avoid the hangups likely to be on the minds of listeners in my particular tradition.

Trips to conferences at seeker-focused churches confirmed these values and added the expectation that messages should include media, drama, accessible illustrations, and LOTS of trendy coffee. I was encouraged to see proclamation as the nutrition unchurched people desperately needed but for which they hadn’t yet acquired a taste. I was invited to envision preachers as skilled chefs who could artfully encapsulate bitter doses of doctrine in palatable spoonfuls of oration spiced with love and grace.

Much of this came across as good, logical advice – nobody wants to bore saints or seekers when talking about something as exquisite as the gospel. The intent was to call proclaimers to be humble, excellent workers who would never besmirch the Good News by bad delivery. The problem, though, lay in the basic, internal posture we were asked to adopt when bringing the Word to sinful, human listeners: deferential apology. As in, “I’m sorry I have to ruin the moment now, but this IS church, and we DO have to mention sin, hell, and the cross of Jesus from time to time. This is going to hurt me more than it hurts you…”

This was also true in worship, in evangelism, and in outreach. Whenever the gospel was proclaimed publicly, we tended to focus on delivery and form, searching for the least common denominator of doctrinal complexity, moral polarity, and inflammatory absolutism. The do-or-die scramble to build the congregation numerically made tickling ears an especially tempting objective for me. While I believe the Lord helped me avoid blatant pandering, I know I was a timorous teacher at certain junctures, speaking the right things with uncomfortable reticence.

About 4-5 years in, something happened that changed my faith in unadorned preaching and evangelism. There were finally enough true converts in our congregation (God had sovereignly used our clumsy proclamation to win believers) that I could track the sources of feedback I received. The recently lost-and-found WERE frustrated with me – but for cutting messages short, trimming content, and watching the clock! Those who had demanded curt, topical homilies were cradle-to-grave types. Denominational veterans claimed to be shielding newbies from discomfort, but the newcomers were clamoring for biblical depth and blunt confrontation.

What was happening? God was exposing a lie that had held us captive for years. He was proving that his Word is fully sufficient, and that true converts thirst for it like a desert thirsts for rain. Many who had grown up in the faith had hearts that were calloused toward the Truth. Years of comfortable church had led them to hear the Word but excuse themselves from practicing it, steadily becoming self-deceived. They projected this hard-heartedness onto newcomers, like the kids in the old Life Cereal commercials: “Try teaching that to Mikey the Seeker – he HATES everything… Heyyyy… Mikey LIKES it!” Unfortunately, some never noticed or accepted that new believers were craving pure spiritual milk and even graduating to meat ahead of them.

So, halfway through our journey, we let go of our timidity and started to change things. I steadily lengthened my messages from 30 minutes to 45 on average and intentionally addressed longer chunks of scripture. We gained this time by ceasing our practice of allowing questions and comments (which sometimes devolved into rebuttals) after the message. I adopted a more expository style, decreased the use of certain video gimmicks and technology, and planned fewer strictly topical series. We increased the use of hymnody and began more public recitation of creeds, confessions, and the Lord’s Prayer. Our evangelism methods focused more on long term service, deep relationship, and truth telling, rather than hit-and-run PR campaigns for our brand. In other words, we began to treat God’s Word as our delight, his commands as anything but burdensome, and the Gospel as something of which we were completely unashamed.

I’d love to tell you it magically fixed everything. It didn’t. It DID give us a new and infinitely more biblically-defensible set of problems, and it DID initiate a protracted season of pruning and refinement that left a far more faithful and joy-filled remnant in the end. You’ll hear more about how that played out in our life, relationships, and governance over my next two posts.

July 24, 2012

From Metro to Retro (1 of 4)

GUEST POST: Josh Blunt

GUEST POST: Josh Blunt

I spent the better part of the last eleven years as a church planter in a small, protestant denomination known as the RCA. I was trained and vetted at the height of the attractional church model’s heyday, when pastors flocked to conferences at Saddleback and Willow Creek for inspiration and when Rob Bell’s fledgling ministry at Mars Hill just seemed quirky and innocuous. Those were days in which innovation was king and the postmodern landscape of the culture around us promised to flow with milk and honey if we could only crack the code and infiltrate it for Jesus.

It was also the dawn of my denomination’s foray into intentional church planting, a season in which young, idealistic, evangelical pastors emerging from seminaries were encouraged to bypass the quagmire of tradition, bureaucracy, and stasis inherent in existing churches. We were enjoined to boldly go where no RCA pastors had gone before, claiming a new share in the Harvest for an increasingly obscure yet historically evangelical family of believers.

The RCA has always been a mixed denomination, boasting of its ability to balance both mainline and evangelical elements in one household. Nevertheless, our denominational landscape at the time seemed divided into two camps:

1) traditional methodology progressive theology = mainline protestantism

2) progressive methodology traditional theology = evangelicalism

The assumption in church planting circles was that, at least in terms of denominational survival, equation #1 led to death and equation #2 was the path to life. In this sense, planters genuinely believed that we and our new churches were going to be the great hope for the next generation of RCA believers.

Many within our little tribe insisted that church planting could restore our dwindling numbers, and even revitalize existing congregations who would parent new, daughter congregations. This plan seemed explicitly biblical and patently apostolic to me then, and it still does now – healthy, biblical, new congregations and church networks DO reach new people and expand the Kingdom. When I started out as a planter, however, most of us assumed that this growth potential would be largely connected to the new congregations’ ability to more nimbly and rapidly deploy progressive, attractional church methodology. In other words, we would adapt to the emerging needs of unbelievers far more easily, having fewer sacred cows to kill along the way.

I can assure you that no one foisted this rationale on me explicitly or activistically. All the appropriate reverence and spiritual language one would expect in churchmanship were judiciously injected along the way. I heard no one openly advocating for a radical abandonment of the ordinary means of grace on which all believers have historically depended for sustenance (God’s Word, the sacraments, and prayer), nor did anyone imply that the true Church should no longer be marked by discipline, purity in proclamation, or right administration of the sacraments. Rather, an excessive optimism about progressive methodology and focus on attractional church accoutrements steadily overshadowed our faith in such means. This blind preference was instilled by the emphasis and tone of well-intentioned and hopeful people, not by any strategic rhetoric from jaded deconstructionists.

In the end, it really doesn’t matter how the idea got into my head or the heads of other planters of my era – what matters is how it affected us and the churches we planted, and how the Holy Spirit has challenged and exposed our assumptions along the way. What I have learned, and what Kevin has graciously invited me to convey through a short series of posts here, is that the future of ministry in historical denominations can’t be reduced to equation #1 OR #2 above. Whether a congregation is being freshly planted, or revitalized over time, I believe the math is something much more akin to this:

3) ordinary, historic methodology orthodox, gospel-focused theology patient, painstaking contextualization = sustainable fruitfulness

Over my next posts, I will offer some of the things I observed over the course of my decade-long church planting journey. I will explain the transformation my congregation and I underwent as our adherence to an attractional, progressive model of methodology inevitably worked against our traditional theology and tore irreparable rifts in the fabric of our fellowship. I will describe the attempts we made to change horses midstream and how they helped. I will also show how the previously lost and unchurched perceived each model, and how the pre-churched and re-churched among us did, as well. These dynamics tended to revolve around three key areas, each of which will be a focus in my remaining posts:

- Proclamation (Preaching of the Word, Worship, Evangelism)

- Life Together (Prayer, Discipleship, Sacraments)

- Unmentionables (Discipline, Conflict, Gender Roles, and Governance)

July 23, 2012

Monday Morning Humor

Three days ago in the summer of 1969, Apollo 11 became the first manned mission to land on the moon. One small step for man; one giant leap for mankind.

Of course, it makes perfect sense that the whole thing could have been a hoax.

(Thanks to my witty readers for proposing this and several forthcoming funnies.)

July 21, 2012

Tragedy and Moral Language

Sadly the massacre in Aurora, Colorado was not the first of its kind. Last year I wrote on “The Tuscon Tragedy and the Gift of Moral Language.” The upshot of the article from 18 months ago may have relevance now as pundits speculate about “what snapped” in the alleged killer:

We instinctively resort to passive speech, unable to bear the thought (let alone utter the words) that a wicked person has perpetrated a wicked crime. The human heart is desperately sinful and capable of despicable sins. Of course, no one commends the crime, but few are willing to condemn the criminal either. In such a world we are no longer moral beings with the propensity for great acts of righteousness and great acts of evil. We are instead, at least when we are bad, the mere product of our circumstances, our society, our upbringing, our biochemistry, or our hurts. The triumph of the therapeutic is nearly complete.

Read the whole thing.

Insider Movement Report

Guest Blogger: Jason Helopoulos

Guest Blogger: Jason Helopoulos

The PCA erected a study committee to examine the Insider Movement in foreign missions and Bible translation. This movement has sought to use language that is less offensive and more culturally sensitive to particular people groups (particularly Muslim) when translating the Scriptures. The key issue has been the translation of words related to Christ’s Sonship. The PCA study committee reported the first half of their report at this year’s General Assembly. This is from the conclusion of the report:

“Indeed, to change or substitute non-familial or social familial terms with the common biological terms in Scripture is to move in a direction contrary to Scriptural intent. Therefore, if a translator seeks to find a more “culturally responsible” or “culturally sensitive” form because the word in the target language arguably contains primary or secondary nuances that differ from the original language (Greek), this aim does not warrant the translator’s selecting a less than explicit term for the Son of God. The biological sonship term may need to be explained, but it cannot be substituted without compromising the revelation of Christ’s person. Translation decisions that violate these parameters functionally eclipse the perspicuous verbal authority of Scripture regarding the Son of God. By truncating the identity of Christ in the minds of the reader, replacement terms can even distort the gospel.

No matter our motivation, there is no pure Gospel apart from the ontological and incarnational sonship of Jesus Christ. Some will protest:sonship and messiah-ship are functionally interchangeable. To be sure, the redemptive-historical theme of Scripture interweaves Christ’s kingly and messianic functions with his sonship status. But the Christological fabric becomes unraveled when we rip the messianic warp from the filial woof. We cannot speak of Christ as Messiah apart from understanding that regal and redemptive functioning in light of him being the Son of God. We also cannot speak of his exalted Sonship apart from his reign as King. Sonship and regal redemptive reign are mutually informative and indivisible; but though the ideas share referentiality, their meanings are not identical.So when the biblical authors employ language laden with such distinct qualities, we have no interpretive right to regard that language as negotiable.

And it is because Jesus is Son of God that we must speak of Christians as adopted sons and daughters of God. We must express Gospel truth in a way that honors the true familial expressions of Scripture, and avoids compromise by unintentional truncation or even well intended yet obstructive contextualization. We cannot speak of the true Gospel apart from the filial character of our union with Christ, for we are united to the Son of God and no one else. The filial and familial language of the Gospel then is not contextually optional; it is transcendently central. Paul’s warnings in Galatians 1 ought give us terrifying pause. Removing familial language eclipses the Christ of the Gospel and it distorts the Gospel of Christ. Ultimately an incognito Christ is a misrepresented Christ. A misrepresented Christ is a false gospel. A false gospel is the turf of the sons of darkness. . . . Some may be mercifully rescued; others will die in their sins. The stakes are that high.”

July 20, 2012

Summer Vacation, Late Have a I Loved Thee

It’s later than usual, but still very much worth the wait. I’ll be on vacation for the next several weeks. Normally, my summer break is largely used as a study leave. This year is a bit different. I’ll still be taking several days to read and write (no arithmetic), but I won’t have time for a big project. That’s because my family is moving houses next week (from Lansing to East Lansing). We’ll be in the new house a grand total of one night before leaving the next morning for Colorado. While in Colorado, my wife and I will leave the kids behind and fly to beautiful Prince Edward Island for a conference masquerading as an anniversary trip. We’ll head back to Colorado, stay another week, and then return home to Michigan in the middle of August.

It’s later than usual, but still very much worth the wait. I’ll be on vacation for the next several weeks. Normally, my summer break is largely used as a study leave. This year is a bit different. I’ll still be taking several days to read and write (no arithmetic), but I won’t have time for a big project. That’s because my family is moving houses next week (from Lansing to East Lansing). We’ll be in the new house a grand total of one night before leaving the next morning for Colorado. While in Colorado, my wife and I will leave the kids behind and fly to beautiful Prince Edward Island for a conference masquerading as an anniversary trip. We’ll head back to Colorado, stay another week, and then return home to Michigan in the middle of August.

Should be busy and should be fun.

During the next few weeks I’ll blog some and mix in several guest bloggers. You’ll hear from Jason Helopoulos (and familiar guest) and other members of our church staff. Josh Blunt, a pastor friend of mine, will lead things off next week with a series of excellent posts about what he learned through the bumps and bruises of church planting.

You may also get a few extra doses of video humor.

July 19, 2012

The Currency of Conviction

It’s been remarkable to see the relativists head for the hills in light of the Penn State sex abuse scandal. The moral outrage has been loud and immense (and justified). I’ve heard no one appeal to diversity, multiculturalism, situational histories, or different ways of being. Every person I’ve talked to, every sports talk commentator I’ve heard, every article I’ve read—they’ve all said the same thing: the abuse was wrong, the cover-up was wrong, the priorities of the school were wrong. Shame on everyone.

It’s been remarkable to see the relativists head for the hills in light of the Penn State sex abuse scandal. The moral outrage has been loud and immense (and justified). I’ve heard no one appeal to diversity, multiculturalism, situational histories, or different ways of being. Every person I’ve talked to, every sports talk commentator I’ve heard, every article I’ve read—they’ve all said the same thing: the abuse was wrong, the cover-up was wrong, the priorities of the school were wrong. Shame on everyone.

Which has me wondering why some sins are so obviously scandalous in our culture and others are not. The difference, as best as I can figure it, has to do with victimization. In general, Americans (like most people I imagine) don’t want innocent people to be hurt through no fault of their own. The equation is simple: if your actions make someone else suffer, they are wrong. It’s easy to see this logic at work in the Jerry Sandusky case. A grown man molests underage boys for his own perverse pleasure and to their great detriment. He wins; they lose. Big time. The moral calculus is clear. And in this case, spot on.

But this line of moral reasoning has its limits. Actions can be wrong whether they visibly hurt someone or not. And actions that provoke suffering or discomfort or disappointment in others (be it emotional or physical) are not always evil. Think of spanking or speed limits or prohibiting harmful substances. Some victimless crimes are still crimes, and sometimes insisting on the right thing produces “victims.”

Our culture is deeply moral. All our fiercest debates–from abortion to homosexuality to budget cuts and taxes–are about morality. What is fair? What is just? What is right? The problem is that too many Americans only trade in one currency of conviction. It’s victimization or nothing at all. This is why the pro-life movement has (rightly) been able to make some headway. Abortion hurts the women who get them and manifestly hurts the children it strikes dead. We can easily show others (if not always persuade them) that abortion causes suffering. There is no higher moral high ground in America.

The same logic works powerfully against Christians when it comes to homosexuality. Since the physical ailments associated with homosexual behavior have been buried deep in the ocean of “don’t you dare go there” there is little accepted moral force left on our side. What could possibly be wrong with two consenting adults expressing their love in private ways mutually agreed upon? No one is hurt by homosexuality. How is your marriage ruined by two other people getting married? Those are the arguments that are almost unassailable given our cultural climate. What’s more, it’s easy to see how advocates of traditional marriage quickly fall on the wrong side of the prevailing moral calculus. We are the oppressors. We are the ones causing innocent people to suffer. We make ourselves happy at the expense of others. Christians are the Jerry Sanduskys of the world.

Think of almost any issue: if you can find a victim, you can make a case. If not, you’ll likely end up the victimizer. So Christians can get quick traction in society by opposing sex trafficking. The oppression is obvious; the sin is scandalous. But we get little traction in opposing premarital sex and great pushback in opposing homosexual behavior. Abortion can go either way because the baby is a victim but denying the woman her choice seems cruel too. Economic matters are also tricky. Cutting the budget may hurt the poor, but confiscatory taxation feels unfair.

The postmodern world knows only one form of moral reasoning: show me the victim. And Christians in this country have played into their hand over the last decades by constantly presenting themselves as oppressed, persecuted, and discriminated against. While all those charges may be true at times, we’ve played that hand so frequently that it’s too late to realize the deck is now stacked against us.

In light of this reality, two things must be done.

First, we must do more to show the long term consequences of seemingly innocent behavior. This is not a call to play the victim card but to do our homework. The sexual revolution of the 1960s seemed like a good idea at the time. But now we know that communities were made weaker, women have not been made happier, and children have been put at greater risk. Just because everyone seems happy with the sin right now doesn’t mean people won’t suffer in the long term. Just look at no-fault divorce.

Second, and more important, as Christians we need to explain the true nature of sin. While oppression is always sin, sin cannot be defined solely as oppression. Sin is lawlessness (I John 3:4). An action is morally praiseworthy or blameworthy based on God’s standard. This definition will not be accepted by many, for God has largely been removed from our culture’s definition of evil. But try we must. The culture war is not the point except to the degree that God is the point. And our God rests too inconsequentially upon our country and our churches. The world needs to see the true nature of sin as God-defiant. Only then will it know the true nature of our sin-defiant Savior.

July 18, 2012

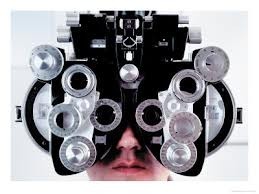

Putting the “Oh!” in Ophthalmology

I’ve long thought that a hundred years hence dentistry will be among our civilization’s more embarrassing moments. Nothing against the profession. Our teeth certainly are less mangled than they used to be. But I assume one day we will progress far enough as a race that scraping the inside of our mouths with metal picks and turbo-suction straws will eventually look like the barbarism it is. Medieval docs used a lot of leeches. We put drills in the back of our throats. Feels like there must be a better way.

I’ve long thought that a hundred years hence dentistry will be among our civilization’s more embarrassing moments. Nothing against the profession. Our teeth certainly are less mangled than they used to be. But I assume one day we will progress far enough as a race that scraping the inside of our mouths with metal picks and turbo-suction straws will eventually look like the barbarism it is. Medieval docs used a lot of leeches. We put drills in the back of our throats. Feels like there must be a better way.

After yesterday, I’m ready to put eye exams in the same category.

Again, lots of love for all the fine folks who keep me seeing year after year. Only the Lord knows where I’d be without the miracle of glasses. (Literally, I would be so lost somewhere only the Lord would know my whereabouts.) But for all the blessings eye doctors have bestowed on the watching world (a fuzzily watching though it be), it’s hard not to conclude that the eye appointment wasn’t crafted at some level of planning by one of the more sinister James Bond villains.

It starts with a line in front of a greeter who directs you to wait in another line where you can check in with a receptionist. Once checked in (at the real check in) you find a seat in the first of your three waiting areas. On the wall is a serious sign stating that no cell phones are allowed in the waiting area. After looking around for optometrists packing heat I conclude that enforcement of this particular statute is likely to be low. So I continue to check my email, hoping to enjoy a few more minutes of good vision before my pupils are the size of silver dollar pancakes.

In the first exam room I am asked a series of questions about my family history. These are more difficult than you might imagine. “Do you have a history of migraines.” Well, I dunno. My mom got headaches, but it wasn’t a bedtime story or anything. Not a part of our history per se. It’s not like we gathered round every Christmas to hear tall tales of the migraines of yesteryear. The DeYoungs have a penchant for living long and going gray at 30 but we haven’t passed down a lot of headache stories. I come prepared to tell my doctor if I smoke, drink, lick frogs, or sniff Sharpies, but I don’t have an oral history of cranial ailments.

Having failed this basic line of questioning, I had no other choice but to begin the first of 17,000 letter reading exercises. They all start with E. After that it’s anybody’s guess. All I know is that they don’t include a lot of easy letters. Not a lot of W’s or K’s or really wide H’s. What you can expect is a C that almost closes at the end and a D with very rounded corners. Pretty much every letter can be made to look like an O if you try. E’s and F’s are almost identical. So are Z’s and S’s. V’s and Us–hah, good luck. Don’t even try for the bottom row. You’ll only embarrass yourself

The second part of the exam is worse. This is where you get tested for rabies of the eye ball (or something like that). As I put my chin into the chin rest and my forehead against that metal strap I can’t decide if I should fear for my life or start whispering something about “Clarice.” As it turns out, I only had to spot a hot air balloon raising in the distance. Very calming. Like a lollipop before the guillotine. Because the next thing I hear is something about two sets of eye drops, the first of which are numbing drops. Hey, woah, hold on a minute. If the first set is to numb my eyes what are your doing with the second set? Setting them on fire? And if dropping foreign liquids from the sky weren’t enough, then they take some doohickey that pulses out and pushes against your eye ball. It’s too close to see what the thing looks like, but I imagine it’s similar to a rock em’ sock em’ robot. With an M.D. Anyway, the lady says laconically, “Try to keep your eyes open. It’s a lot harder when you keep closing your eyes.” Yeah, I bet it’s a lot harder. A lot harder to poke me in the eye! I don’t tug on Superman’s cape. I don’t spit into the wind. I don’t pull the mask off the ole Lone Ranger. And I don’t keep my eyes open when people stick things in them.

Well by now I’m on to my third waiting room anticipating seeing the real doctor for the first time. As I think wistfully about the dentist, I can tell the Secret Drops of Nimh are taking effect. I can’t see straight and I’m not sure I ever will again. I pound out every text as if it were my last. Who knows what those second drops are doing? And heaven forbid if the numbing drops wear off. All I know is that my pupils are dilating and every flicker of florescent shines like a thousand burning suns. I see old men called into the doctor’s room. I don’t see them return. But then again, I’m having a hard time seeing anything.

As I enter the doctor’s office she cheerfully asks me how I am doing. I tell her “okay.” Just okay, she says. “Well, I am having my eyes jammed out of their sockets” I think to myself. She really is a nice woman and a good doctor. But I can’t take any more eye charts or any more “Number One…or Number Two” tests. They all look the same. Number One is kind of meh and Number Two is pretty much the same meh. There’s a lot of pressure with this part of the exam. It comes at the end when they are trying to figure out your prescription. A wrong answer could doom you to partial blindness for the next year. You’ll be sitting befuddled at a stop sign thinking it says “Stoo” because you chose Number One instead of Number Two. For the first time I can recall, my doctor actually told me when I did well. She’d be silent as I picked three Number Ones in a row and then let out a “Good” when I finally tried Number Two. For all I know the ophthalmologists get together after work, put back a few shots of saline, and swap stories about all the yahoos who think Number One is actually clearer than Number Two. They must chortle themselves silly knowing that Number Three is just Number One recycled.

I try to pick out a new pair of glasses so I can have something to show for the morning gauntlet. But apparently my lens are going to be as thick as scones. That limits my options. As does the realization that I, as the woman at the desk puts it, have “narrow pupils,” which is the nice way of saying, “Your head is long and skinny and your eyes are too close together.” In the end, I can’t bring myself to spend a week’s salary on glasses that will make me look like one of the Traveling Wilburys. So I settle for paying my bill and getting a free RoboCop visor-shield to protect my dilated pupils from melting like a Gremlin in the sunlight. It’s all a small price to pay, I suppose, for having 20/20 vision the rest of year. A new pair of glasses sure beats a poke in the eye. I’m just waiting for the technological breakthrough that will allow for one without the other.

July 17, 2012

Obligation, Stewardship, and the Poor

The Bible is full of explicit commands and implicit commendations to help the poor.

One thinks of the gleaning laws in Deuteronomy 25 or the command to “open wide your hand to your brother, to the needy and to the poor” in Deuteronomy 15. We can read about Job’s heart for the needy and oppressed in Job 29 to 31 or of God’s special concern for the poor in Psalm 35 and Proverbs 14.

We also know Jesus was moved with compassion for the weak, the harassed, and the helpless (Matt. 9:35-36). We see in the early church that the needs of the poor and distressed was a constant priority (Acts 4:34-35; Acts 11:30; Gal. 2:10). And frequently we are command to love one another not only with words but in the concrete actions of generosity and material support (James 2:15-17; 1 John 3:16-18). Even the elders, who are to be devoted to the word of God and prayer, were told by Paul to help the weak (Acts 20:35).

Clearly, God cares about the poor and wants us to care about them too.

But how?

Maybe you’re thinking: “Okay, I’m a Christian. I know God cares about the poor. I know I should care about the poor too. I do care about the poor. So what is my responsibility to help them?”

HOW SHOULD WE HELP THE POOR?

The question is deceptively complex. It’s very easy (and altogether biblical) for folks to insist that Christians ought to “be concerned about the needy” or “do something about the poor.” That’s powerfully true, but it doesn’t say nearly enough. In an age when easy travel and ubiquitous WiFi can connect us to billions of needs around the planet, how do we determine whom to care for and when to do something?

If Christians have an obligation to help the poor (and we do), does that mean we are obligated to help everyone everywhere in the same way in any circumstance of need? How should we think about our responsibility to help the poor?

I believe two critical principles can help us answer that question.

Principle 1: We are most responsible to help those closest to us.

In general, we ought to think of our sphere of responsibility as having expanding concentric circles. In the middle, with the closest circle, is our family. “If anyone does not provide for his relatives, and especially members of his household, he has denied the faith and is worse than an unbeliever” (1 Tim. 5:8). This means that if you have the ability to help your (not lazy) children and don’t, you are a pagan. If you have the necessary resources and yet you neglect your aging, helpless parents, you have turned from Christ.

In the next circle we have members of our church community. The principle is really the same: just as we have an obligation to provide for our natural family, so we ought to provide for our spiritual family. The New Testament frequently enjoins us—by example and by explicit command and warning—to care for the needs of the Christians in our local churches (Acts 2:45; 4:32-37; 6:1-6; James 2:15-17; 1 John 3:16-17). If there is a Christian in your church who is materially devastated by calamity or infirmity and we who have resources in abundance do nothing to help, we prove that we do not truly have the love of Christ or know Christ himself.

Next we have members of our Christian family whose needs are more distant. We still have an obligation to care for our brothers and sisters, but the Bible speaks less forcefully the farther away the needs become. So in 2 Corinthians 8 and 9 Paul clearly wants the Christians in Achaia to generously support the Christians in Macedonia, but he is stops short of laying down a command (8:8) or exacting a contribution from them (9:5).

In the outer circle we have the needs of non-Christians in the world. The church should still be ready to do good to all people, but this support is less obligatory than what we owe to Christians and is framed by “opportunity” rather than requirement (Gal. 6:10).

One other category should be mentioned. Sometimes we come across needs that are so obvious, so immediate, and we are in such a unique position to help, that it would be wrong to ignore them, whether the person is a family member, a church member, or a complete stranger. Regardless of prior affiliation or acquaintance the “closeness” of the need is too close to ignore. This seems to be the point of Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37) and the story of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31). If we see a child drowning in the pool, we should dive in. If a woman is being beaten up, we should intervene. If a minivan has collapsed on a barren stretch of highway, we should stop and lend a hand. The concentric circles are helpful as a general guideline for care, but they should not be used to justify the lack of care when someone needs our assistance right here and right now.

Principle 2: We are most responsible to help those least able to help themselves.

Here again we can think of expanding concentric circles of responsibility. The progression with this principle is a little different because if we go out far enough in these circles we are actually commanded not to help. So the logic needs to be tweaked, but the basic imagery is still useful.

At the center, we have those people whose situation is most desperate because their options are most limited. In the Bible this prototypically meant “orphans and widows” (James 1:27). But the principle applies to any person or persons who will crash unless we provide a safety net. Caring for believers in prison was another classic example in the ancient world (Heb. 10:34).

Outside of this inner circle, we find those who are less desperate but still depend on others for their well-being. In the New Testament this meant being generous with hospitality, especially to travelling evangelists who relied on the kindness of their brothers and sisters for their mission (Matt. 10:40-42; 25:31-46).

Next, we have those Christians with long term needs. The striking thing about almost all of the “poor” passages in Scripture is that they envision immediate, short-term acts of charity. There is nothing about community development (which doesn’t make it unbiblical) and only a little about addressing situations of ongoing need. By putting these situations in this circle I don’t mean to imply that we ought only to care about quick fixes. The point, rather, is that we must think more critically before committing to long-term assistance. In both Acts 6 and 1 Timothy 5 we see church leaders working hard to develop a fair and sustainable process for the regular distribution of resources to the poor. In particular, we see in 1 Timothy 5 that the widows who went on the official rolls had to meet certain requirements. The women had to be godly, older Christians in order to receive the church’s care (1 Tim. 5:9-16). No doubt, the church sympathized with almost all widows, but they had to be wise with their resources. They did not want to support young women who could get married or fall into idle sinfulness. And as for the other requirements, I imagine the church knew it had to draw the line somewhere and requiring “a reputation of good works” ensured that the widows on the rolls were genuine, faithful, known Christians and not just busybodies looking for a handout.

In the farthest circle out we have people that must positively not be helped by the church. First, Christians should not provide hospitality for false teachers or do anything that would aid and abet their wicked works (2 John 10-11). Second, Christians should not support able-bodied persons who could provide for themselves, but prefer laziness instead (1 Thess. 4:11-12; 5:14; Prov. 24:30-34). The apostolic principle is clear: “If anyone is not willing to work, let him not eat” (2 Thess. 3:10). In fact, Paul insists that church discipline be exercised on those who persist in idleness (2 Thess. 3:14). The Christian responsibility to charity does not extend to those who expect others to do for them what they could do for themselves. Helping the poor in these circumstances is no help at all.

BASIC PRINCIPLES FOR WISE DECISIONS

Obviously, I have not begun to answer the myriad of “What if…?” and “What about…?” questions that arise when churches start to work on actually caring for the poor. I can’t give specific answers for every situation because the Bible doesn’t give those answers either.

But what the Bible does do is provide the basic principles to inform wise decision-making. As you consider your personal obligation to the poor and your church’s corporate obligation, keep in mind these two principles: proximity and necessity. The closer the person is to you (relationally, spiritually, or geographically) and the more acute the need (because it’s immediate, urgent, or within your unique power to provide), the greater your obligation is to give, assist, and get involved. The farther out you go in either circle, the less “ought” you should feel and the more caution you should take.

But please don’t use the two circles of responsibility as an excuse for apathy and inactivity. Use the biblical principles to help you set priorities wisely and respond in ways that are sustainable and effective.

This article originally appeared in the 9Marks Journal.