Eleanor Arnason's Blog, page 68

October 9, 2011

OWS

Friday, when Lyda and I went to the Occupy Minnesota demonstration in Minneapolis, was cephalopod awareness day.

Published on October 09, 2011 09:28

October 7, 2011

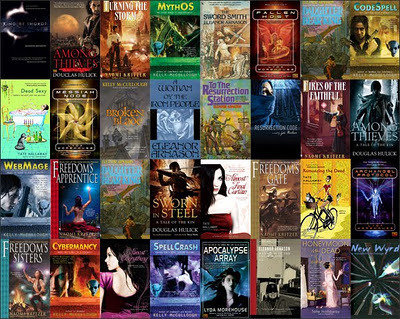

Flyer for St. Paul Art Crawl This Weekend

If you are wondering what the flyers are about, I signed up for a table at the St. Paul Art Crawl happening this weekend. It looks as if I will end up caring for the table on my own, since the other Wyrdsmiths can't make the event. The image is pulled off the website that Bill Henry designed for the Wyrdsmith Writing Group. As you can probably figure out, it's many of our book covers, attractively arranged. There's a little text, which didn't come through when I loaded the image. Anyway, it represents the rest of the group in absentia; and I will represent myself.

Published on October 07, 2011 16:17

Flyer for St. Paul Art Crawl This Weekend

I'm not crazy about the look of this, but the teeny print tells people they can find my work on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Kindle and Nook. Important information.

Published on October 07, 2011 16:15

September 26, 2011

NASA APOD

Part of Mars is defrosting. Around the South Pole of Mars, toward the end of every Martian summer, the warm weather causes a section of the vast carbon-dioxide ice cap to evaporate. Pits begin to appear and expand where the carbon dioxide dry ice sublimates directly into gas. These ice sheet pits may appear to be lined with gold, but the precise composition of the dust that highlights the pit walls actually remains unknown. The circular depressions toward the image center measure about 60 meters across. The HiRISE camera aboard the Mars-orbiting Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter captured the above image in late July. In the next few months, as Mars continues its journey around the Sun, colder seasons will prevail, and the thin air will turn chilly enough not only to stop the defrosting but once again freeze out more layers of solid carbon dioxide.

Published on September 26, 2011 17:16

September 21, 2011

Book Review

I'm reading Global Slump by David McNally, one of the books I bought at the book fair.

He spends a lot of time arguing that the current economic crisis does not mean capitalism is finished. I agree with this. Capitalism has proved very resilient over the past two centuries. He also makes clear how destructive capitalism is. This makes the book pretty depressing: an awful economic system that seems likely to continue.

He does talk about strikes, mass demonstrations and revolutions in countries like Bolivia, Mexico, France and Greece. But this comes fairly late in the book, around the time the reader is about to give up hope of any change for the better. And he does not seem sure that change for the better is possible: all these attempts to stop capitalism have failed or may well fail.

He also diverts, I can't remember where, to the utterly awfulness of the USSR, when it existed. I'm not sure what the point of this is, since he is talking about the current slump, in a world where the Soviet Union has not existed for 20 years. Whatever his reason, he is a describing a world where capitalism is awful and alternatives to capitalism are unlikely, unstable or equally bad.

I guess I have some questions: are all governments and economic systems in the world equally bad? Is there no variation? Is human history over the past 200 years all downhill? Have there been no improvements? Consider this, a lovely little four-minute video showing changes in life expectancy and income by country over the past 200 years. If Professor Hans Rosling is right, people in most countries have more income and are longer-lived than 200 years ago. This seems like an improvement.

As far as I have gotten, McNally hasn't addressed the big questions: global warming, most of all, then peak oil and depletion of many natural resources. How does a system like capitalism, which requires growth, continue?

He spends a lot of time arguing that the current economic crisis does not mean capitalism is finished. I agree with this. Capitalism has proved very resilient over the past two centuries. He also makes clear how destructive capitalism is. This makes the book pretty depressing: an awful economic system that seems likely to continue.

He does talk about strikes, mass demonstrations and revolutions in countries like Bolivia, Mexico, France and Greece. But this comes fairly late in the book, around the time the reader is about to give up hope of any change for the better. And he does not seem sure that change for the better is possible: all these attempts to stop capitalism have failed or may well fail.

He also diverts, I can't remember where, to the utterly awfulness of the USSR, when it existed. I'm not sure what the point of this is, since he is talking about the current slump, in a world where the Soviet Union has not existed for 20 years. Whatever his reason, he is a describing a world where capitalism is awful and alternatives to capitalism are unlikely, unstable or equally bad.

I guess I have some questions: are all governments and economic systems in the world equally bad? Is there no variation? Is human history over the past 200 years all downhill? Have there been no improvements? Consider this, a lovely little four-minute video showing changes in life expectancy and income by country over the past 200 years. If Professor Hans Rosling is right, people in most countries have more income and are longer-lived than 200 years ago. This seems like an improvement.

As far as I have gotten, McNally hasn't addressed the big questions: global warming, most of all, then peak oil and depletion of many natural resources. How does a system like capitalism, which requires growth, continue?

Published on September 21, 2011 09:08

Current Conditions

The previous post got long enough. I am continuing here.

I guess I have three objections to McNally's book, as far as I have read. It may turn around, and I may eat my words.

1) There is the corny line about "allowing the perfect to be the enemy of the good." I don't like the line, because it is often used to justify actions that are inadequate or flat out not good. However, McNally seems to find fault in pretty much every social organization. Modern history is the history of people struggling to improve their lives. They have not utterly failed. There have been comparative successes. We in the US are not living in the 19th century, when people worked 14 hours a day for less than living wages. There are people -- many people -- living in that kind of misery in the world, and we need to work to end exploitation everywhere. And we may get pushed back to that kind of life, as the world economy and ecology collapses. But we should admit there has been some success and there is the possibility of more success. Despair is not a good basis for action.

2) McNally does not seem aware of how fragile the world economy is, at least according to many capitalist economists. The governments of Europe and the US are making serious mistakes in trying to cope with the current recession/depression. Much of the world depends on the US market, which is contracting. Attempts to impose austerity -- in Europe especially -- have led to strikes and mass demonstrations and may lead to revolution in some countries. If austerity succeeds, then the world will sink deeper into recession/depression, since modern western economies are dependent on consumer spending. I think all these problems are fixable, but not if the current morons remain in power.

3) The world is facing huge problems, which I mentioned in my previous post: global warming, depletion of resources, degradation of land and water. Capitalism, historically, has relied on expropriation of resources -- the flood of New World silver that came into Europe after 1492 and helped fund the rise of capitalism; land enclosure in England, the first capitalist power; the conquest of Africa and Asia, which provided Europe with resources and markets... And capitalism has always relied on competition and growth. Competition means several companies are trying to fill the needs of a single market, which means overproduction and waste. This supposed to be efficient. It isn't. It leads to periodic crashes due to overproduction, and it means a lot of stuff is thrown away, because it isn't needed. The economist Schumpeter called this "creative destruction." It might as well be called simple destruction.

In order to work, capitalism needs to use up a lot of everything. What happens when it has used up most of the world?

What happens when global warming hits hard, when crops fail -- as they are doing now, countries flood or suffer severe droughts? And when we have to change the world entirely in order to survive? Can capitalism -- a system of competition, growth and waste -- survive?

I guess I have three objections to McNally's book, as far as I have read. It may turn around, and I may eat my words.

1) There is the corny line about "allowing the perfect to be the enemy of the good." I don't like the line, because it is often used to justify actions that are inadequate or flat out not good. However, McNally seems to find fault in pretty much every social organization. Modern history is the history of people struggling to improve their lives. They have not utterly failed. There have been comparative successes. We in the US are not living in the 19th century, when people worked 14 hours a day for less than living wages. There are people -- many people -- living in that kind of misery in the world, and we need to work to end exploitation everywhere. And we may get pushed back to that kind of life, as the world economy and ecology collapses. But we should admit there has been some success and there is the possibility of more success. Despair is not a good basis for action.

2) McNally does not seem aware of how fragile the world economy is, at least according to many capitalist economists. The governments of Europe and the US are making serious mistakes in trying to cope with the current recession/depression. Much of the world depends on the US market, which is contracting. Attempts to impose austerity -- in Europe especially -- have led to strikes and mass demonstrations and may lead to revolution in some countries. If austerity succeeds, then the world will sink deeper into recession/depression, since modern western economies are dependent on consumer spending. I think all these problems are fixable, but not if the current morons remain in power.

3) The world is facing huge problems, which I mentioned in my previous post: global warming, depletion of resources, degradation of land and water. Capitalism, historically, has relied on expropriation of resources -- the flood of New World silver that came into Europe after 1492 and helped fund the rise of capitalism; land enclosure in England, the first capitalist power; the conquest of Africa and Asia, which provided Europe with resources and markets... And capitalism has always relied on competition and growth. Competition means several companies are trying to fill the needs of a single market, which means overproduction and waste. This supposed to be efficient. It isn't. It leads to periodic crashes due to overproduction, and it means a lot of stuff is thrown away, because it isn't needed. The economist Schumpeter called this "creative destruction." It might as well be called simple destruction.

In order to work, capitalism needs to use up a lot of everything. What happens when it has used up most of the world?

What happens when global warming hits hard, when crops fail -- as they are doing now, countries flood or suffer severe droughts? And when we have to change the world entirely in order to survive? Can capitalism -- a system of competition, growth and waste -- survive?

Published on September 21, 2011 08:59

Current Condiitions

The previous post got long enough. I am continuing here.

I guess I have three objections to McNally's book, as far as I have read. It may turn around, and I may eat my words.

1) There is the corny line about "allowing the perfect to be the enemy of the good." I don't like the line, because it is often used to justify actions that are inadequate or flat out not good. However, McNally seems to find fault in pretty much every social organization. Modern history is the history of people struggling to improve their lives. They have not utterly failed. There have been comparative successes. We in the US are not living in the 19th century, when people worked 14 hours a day for less than living wages. There are people -- many people -- living in that kind of misery in the world, and we need to work to end exploitation everywhere. And we may get pushed back to that kind of life, as the world economy and ecology collapses. But we should admit there has been some success and there is the possibility of more success. Despair is not a good basis for action.

2) McNally does not seem aware of how fragile the world economy is, at least according to many capitalist economists. The governments of Europe and the US are making serious mistakes in trying to cope with the current recession/depression. Much of the world depends on the US market, which is contracting. Attempts to impose austerity -- in Europe especially -- have led to strikes and mass demonstrations and may lead to revolution in some countries. If austerity succeeds, then the world will sink deeper into recession/depression, since modern western economies are dependent on consumer spending. I think all these problems are fixable, but not if the current morons remain in power.

3) The world is facing huge problems, which I mentioned in my previous post: global warming, depletion of resources, degradation of land and water. Capitalism, historically, has relied on expropriation of resources -- the flood of New World silver that came into Europe after 1492 and helped fund the rise of capitalism; land enclosure in England, the first capitalist power; the conquest of Africa and Asia, which provided Europe with resources and markets... And capitalism has always relied on competition and growth. Competition means several companies are trying to fill the needs of a single market, which means overproduction and waste. This supposed to be efficient. It isn't. It leads to periodic crashes due to overproduction, and it means a lot of stuff is thrown away, because it isn't needed. The economist Schumpeter called this "creative destruction." It might as well be called simple destruction.

In order to work, capitalism needs to use up a lot of everything. What happens when it has used up most of the world?

What happens when global warming hits hard, when crops fail -- as they are doing now, countries flood or suffer severe droughts? And when we have to change the world entirely in order to survive? Can capitalism -- a system of competition, growth and waste -- survive?

I guess I have three objections to McNally's book, as far as I have read. It may turn around, and I may eat my words.

1) There is the corny line about "allowing the perfect to be the enemy of the good." I don't like the line, because it is often used to justify actions that are inadequate or flat out not good. However, McNally seems to find fault in pretty much every social organization. Modern history is the history of people struggling to improve their lives. They have not utterly failed. There have been comparative successes. We in the US are not living in the 19th century, when people worked 14 hours a day for less than living wages. There are people -- many people -- living in that kind of misery in the world, and we need to work to end exploitation everywhere. And we may get pushed back to that kind of life, as the world economy and ecology collapses. But we should admit there has been some success and there is the possibility of more success. Despair is not a good basis for action.

2) McNally does not seem aware of how fragile the world economy is, at least according to many capitalist economists. The governments of Europe and the US are making serious mistakes in trying to cope with the current recession/depression. Much of the world depends on the US market, which is contracting. Attempts to impose austerity -- in Europe especially -- have led to strikes and mass demonstrations and may lead to revolution in some countries. If austerity succeeds, then the world will sink deeper into recession/depression, since modern western economies are dependent on consumer spending. I think all these problems are fixable, but not if the current morons remain in power.

3) The world is facing huge problems, which I mentioned in my previous post: global warming, depletion of resources, degradation of land and water. Capitalism, historically, has relied on expropriation of resources -- the flood of New World silver that came into Europe after 1492 and helped fund the rise of capitalism; land enclosure in England, the first capitalist power; the conquest of Africa and Asia, which provided Europe with resources and markets... And capitalism has always relied on competition and growth. Competition means several companies are trying to fill the needs of a single market, which means overproduction and waste. This supposed to be efficient. It isn't. It leads to periodic crashes due to overproduction, and it means a lot of stuff is thrown away, because it isn't needed. The economist Schumpeter called this "creative destruction." It might as well be called simple destruction.

In order to work, capitalism needs to use up a lot of everything. What happens when it has used up most of the world?

What happens when global warming hits hard, when crops fail -- as they are doing now, countries flood or suffer severe droughts? And when we have to change the world entirely in order to survive? Can capitalism -- a system of competition, growth and waste -- survive?

Published on September 21, 2011 08:16

September 18, 2011

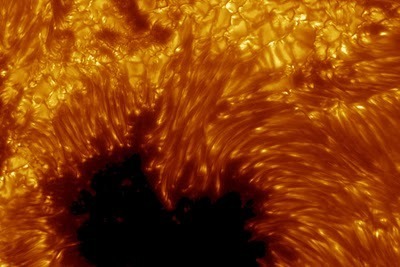

Sunspot - NASA APOD

Here is one of the sharper views of the Sun ever taken. This stunning image shows remarkable details of a dark sunspot across the image bottom and numerous boiling granules which appear like kernels of corn across the top. Taken in 2002, the picture was made using the Swedish Solar Telescope operating on the Canary Island of La Palma. The high resolution image was achieved using sophisticated adaptive optics, digital image stacking, and other processing techniques to counter the blurring effect of Earth's atmosphere. Currently a sunspot group is crossing the Sun that is so large it can be easily seen by the cautious observer even without magnification.

Published on September 18, 2011 09:03

September 17, 2011

Cucumbers

The Farmers Market was gorgeous today -- tomatoes, green peppers, squash, apples, in broad trays and big baskets. I bought a baguette and some cucumbers. Amazing how happy this made me.

That led to thinking about Praxilla of Sicyon, a 5th century BC Greek poet. One of her poems became a proverb: "As silly as Praxilla's Adonis," because she had the dying Adonis speaking as follows of the world he was leaving:

Anyway, I wrote a poem titled "Revolutionary Cucumber Poem," in imitation of Praxilla:

I'm not sure I'm making sense. I'm asking what the great ideas and causes are in the absence of ordinary life, and what is ordinary life in the absence of the great ideas and causes.

Cucumbers are precious; so are pears and apples. Eat them when they are ripe, but not overripe.

That led to thinking about Praxilla of Sicyon, a 5th century BC Greek poet. One of her poems became a proverb: "As silly as Praxilla's Adonis," because she had the dying Adonis speaking as follows of the world he was leaving:

Loveliest of what I leave behind is the sunlight,The ancient Greeks thought it was silly to mourn cucumbers and pears and apples. Only a woman would write anything this stupid.

and loveliest after that the shining stars, and the moon's face,

but also cucumbers that are ripe, and pears, and apples.

Anyway, I wrote a poem titled "Revolutionary Cucumber Poem," in imitation of Praxilla:

It's one thing to raise the people's flag,

blood-red, from the hand of a fallen comrade,

and another thing to take joy in cucumbers

at the downtown Farmer's Market.

But what is the flag

without the cucumbers

and the farmers who grew them

and the people buying produce?

And what are the cucumbers --

thick and green and crisp in their basket --

without the flag?

I'm not sure I'm making sense. I'm asking what the great ideas and causes are in the absence of ordinary life, and what is ordinary life in the absence of the great ideas and causes.

Cucumbers are precious; so are pears and apples. Eat them when they are ripe, but not overripe.

Published on September 17, 2011 11:52

Radical History

Terry Bisson's talk was about the historical research he has done for various projects. Interesting stuff. He has led an interesting life, as well as writing truly wonderful science fiction.

There was supposed to be a historian there, and he and Terry were supposed to talk about researching radical history. But the historian was at home, having done something terrible to his back. Anyway, I started thinking about history and science fiction. I'm going to make some huge generalizations, because I'm thinking out loud or maybe in electrons...

There are three fundamental lies told by traditional histories:

1) History is made by famous men, rather than by ordinary people.

2) The broad trends of history are smooth.

3) The broad trends of history are inevitable.

I'm not sure I can explain all this. I'm not sure I understand what I'm saying. But here goes.

1) History to me is social change, and it is made by everyone. A lot of it is made by people changing their living habits, the tools they use, the crops they grow and how they grow those crops. According to the anthropologist Jack Weatherford, Russia and Prussia became great empires, because the potato was imported from the new world. It grows more reliably in northern climates than do grains. Before the potato, Russia and Prussia were subject to regular famines. After, they could feed their populations and their armies.

2) History tends to be taught in Ages, which are broadly described. This gives the illusion that history is smooth. In fact, it is full of small changes and struggles. By ignoring these, historians give the impression that ordinary people have almost no part in history. They emerge -- briefly -- in great popular struggles and revolutions, and then disappear. The great demonstrations in Egypt this year, which brought down the government, were preceded by years of labor struggle, which was not covered in the US media. Often, the struggles are lost. They rarely achieve everything hoped for. But they continue. The placid 1950s in America -- the golden age for conservatives -- had strikes by a union movement that was still comparatively strong, the struggle against McCarthyism, the early years of the Civil Rights Movement, the Beat Generation and the rise of rock music, which turned political in the 1960s and remains a form of popular expression.

3) History tends to taught as if it's mostly inevitable. In fact, it seems to me, it is often contingent. Things could turn out differently. This was where science fiction and alternative history come in: they show history as mutable. Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle is about an America where the Axis Powers won the war. Terry Bisson's Fire on the Mountain is about an America where John Brown succeeded at Harper's Ferry, and the final result is a black republic in the South.

So a radical history, it seems to me, ought to be popular, bumpy, turbulent, active and contingent. It ought to show the achievements of ordinary people, and the ways that ordinary life changes over time. All of American history is seething with struggle: labor struggles, farmers movements -- which were sometimes guerrilla wars, the Abolitionists, the struggle of American Indians to save some part of their native lands, Feminism, the struggle of every ethnic group to overcome prejudice. If you don't see these struggles and how they changed society and how people have been able to survive and sometimes win, they you will believe that the bosses always come out on top, and There Is No Alternative, in the famous words of Margaret Thatcher.

There was supposed to be a historian there, and he and Terry were supposed to talk about researching radical history. But the historian was at home, having done something terrible to his back. Anyway, I started thinking about history and science fiction. I'm going to make some huge generalizations, because I'm thinking out loud or maybe in electrons...

There are three fundamental lies told by traditional histories:

1) History is made by famous men, rather than by ordinary people.

2) The broad trends of history are smooth.

3) The broad trends of history are inevitable.

I'm not sure I can explain all this. I'm not sure I understand what I'm saying. But here goes.

1) History to me is social change, and it is made by everyone. A lot of it is made by people changing their living habits, the tools they use, the crops they grow and how they grow those crops. According to the anthropologist Jack Weatherford, Russia and Prussia became great empires, because the potato was imported from the new world. It grows more reliably in northern climates than do grains. Before the potato, Russia and Prussia were subject to regular famines. After, they could feed their populations and their armies.

2) History tends to be taught in Ages, which are broadly described. This gives the illusion that history is smooth. In fact, it is full of small changes and struggles. By ignoring these, historians give the impression that ordinary people have almost no part in history. They emerge -- briefly -- in great popular struggles and revolutions, and then disappear. The great demonstrations in Egypt this year, which brought down the government, were preceded by years of labor struggle, which was not covered in the US media. Often, the struggles are lost. They rarely achieve everything hoped for. But they continue. The placid 1950s in America -- the golden age for conservatives -- had strikes by a union movement that was still comparatively strong, the struggle against McCarthyism, the early years of the Civil Rights Movement, the Beat Generation and the rise of rock music, which turned political in the 1960s and remains a form of popular expression.

3) History tends to taught as if it's mostly inevitable. In fact, it seems to me, it is often contingent. Things could turn out differently. This was where science fiction and alternative history come in: they show history as mutable. Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle is about an America where the Axis Powers won the war. Terry Bisson's Fire on the Mountain is about an America where John Brown succeeded at Harper's Ferry, and the final result is a black republic in the South.

So a radical history, it seems to me, ought to be popular, bumpy, turbulent, active and contingent. It ought to show the achievements of ordinary people, and the ways that ordinary life changes over time. All of American history is seething with struggle: labor struggles, farmers movements -- which were sometimes guerrilla wars, the Abolitionists, the struggle of American Indians to save some part of their native lands, Feminism, the struggle of every ethnic group to overcome prejudice. If you don't see these struggles and how they changed society and how people have been able to survive and sometimes win, they you will believe that the bosses always come out on top, and There Is No Alternative, in the famous words of Margaret Thatcher.

Published on September 17, 2011 08:08

Eleanor Arnason's Blog

- Eleanor Arnason's profile

- 73 followers

Eleanor Arnason isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.