Ken MacLeod's Blog, page 27

January 10, 2011

A lesson from the classics

Hector was first to speak. "I will-no longer fly you, son of Peleus," said he, "as I have been doing hitherto. Three times have I fled round the mighty city of Priam, without daring to withstand you, but now, let me either slay or be slain, for I am in the mind to face you. Let us, then, give pledges to one another by our gods, who are the fittest witnesses and guardians of all covenants; let it be agreed between us that if Jove vouchsafes me the longer stay and I take your life, I am not to treat your dead body in any unseemly fashion, but when I have stripped you of your armour, I am to give up your body to the Achaeans. And do you likewise."

Achilles glared at him and answered, "Fool, prate not to me about covenants. There can be no covenants between men and lions, wolves and lambs can never be of one mind, but hate each other out and out an through. Therefore there can be no understanding between you and me, nor may there be any covenants between us, till one or other shall fall and glut grim Mars with his life's blood."

The Illiad

Never make nice.

Published on January 10, 2011 21:21

January 5, 2011

From the Old Space Age

The latest issue of Redstone Science Fiction has, among other delights, a reprint of my 2008-Hugo-shortlisted story Who's Afraid of Wolf 359?. First published in the anthology The New Space Opera, edited by Gardner Dozois and Jonathan Strahan (Eos Books, Harvester, 2006) the story is set in the same universe as my novel Learning the World. In that universe, the common notion of prehistory is of a time when people lived in caves, on the Moon.

But let's not knock the people of the Old Space Age! Take a look at this striking image of the solar transit of the International Space Station during yesterday's partial eclipse, and marvel.

But let's not knock the people of the Old Space Age! Take a look at this striking image of the solar transit of the International Space Station during yesterday's partial eclipse, and marvel.

Published on January 05, 2011 10:00

January 2, 2011

Jim Cannon's socialist hope

Speaking of optimism, here's the peroration of a speech that James P. Cannon, an American socialist, made in 1953. Cannon's deeds have prevailed all right. You may never have heard of him, but the world we live in would be noticeably different if Cannon had never lived, or had made different choices. Ignazio Silone once said that the final conflict would be between the communists and the ex-communists. One less-than-final but still significant conflict today, that over the left's response to war, is between those who work and think along the lines that Cannon laid down and those - the inheritors, whether they know it or not, of Shachtman on the one hand and of Stalinism on the other - who don't. Without Cannon, there wouldn't be an antiwar movement. There would be a 'peace' movement, begging the warmakers to see sense. There would be a 'Decent left', cheering the warmakers on. And that - give or take a few fringe intransigents - would be that.

Cannon's deeds have prevailed all right. You may never have heard of him, but the world we live in would be noticeably different if Cannon had never lived, or had made different choices. Ignazio Silone once said that the final conflict would be between the communists and the ex-communists. One less-than-final but still significant conflict today, that over the left's response to war, is between those who work and think along the lines that Cannon laid down and those - the inheritors, whether they know it or not, of Shachtman on the one hand and of Stalinism on the other - who don't. Without Cannon, there wouldn't be an antiwar movement. There would be a 'peace' movement, begging the warmakers to see sense. There would be a 'Decent left', cheering the warmakers on. And that - give or take a few fringe intransigents - would be that.

How did Cannon acquire the confidence that the cause for which he fought had 'social evolution' on its side? As a youth he walked into a meeting to hear a lecture on 'Marx and Darwin'. That lecture, and further study, convinced him 'theoretically - and that is the firmest conviction there is' that capitalism is inseparable from crises and wars, that the great majority of working people would sooner or later be compelled to move into action against these crises and wars, and that they would establish as capitalism's successor system one of global co-operation for abundance, peace, and freedom. 'The victory of Socialist America is already written in the stars.'

Nothing that has happened since his death in 1974 would have surprised him if he'd lived to see it, or disillusioned him. He had no illusions. Cannon's theoretical conviction allowed him to face unflinchingly the terrible realities of the 20th Century: World War, the rise of Stalinism, the Depression, the Yezhovschina, the Second World War, the Holocaust, the atomic bombings, the Stalinist labour camps, the Cold War and the colonial wars. Unlike some, he faced and fought them all while they happened, in real time. He never gave an inch.

We're all so much more sophisticated now.

All will be artists. All will be workers and students, builders and creators. All will be free and equal. Human solidarity will encircle the globe and conquer it and subordinate it to the uses of man.

That, my friends, is not an idle speculation. That is the realistic perspective of our great movement. We ourselves are not privileged to live in the socialist society of the future, which Jack London, in his far-reaching aspiration, called the Golden Future. It is our destiny, here and now, to live in the time of the decay and death agony of capitalism. It is our task to wade through the blood and filth of this outmoded, dying system. Our mission is to clear it away. That is our struggle, our law of life.

We cannot be citizens of the socialist future, except by anticipation. But it is precisely this anticipation, this vision of the future, that fits us for our role as soldiers of the revolution, soldiers of the liberation war of humanity. And that, I think, is the highest privilege today, the occupation most worthy of a civilised man. No matter whether we personally see the dawn of socialism or not, no matter what our personal fate may be, the cause for which we fight has social evolution on its side and is therefore invincible. It will conquer and bring all mankind a new day.

It is enough for us, I think, if we do our part to hasten on the day. That's what we're here for. That's all the incentive we need. And the confidence that we are right and that our cause will prevail, is all the reward we need. That's what the socialist poet, William Morris, had in mind, when he called us to

Join in the only battle

wherein no man can fail

for whoso fadeth and dieth

yet his deeds shall still prevail.

Cannon's deeds have prevailed all right. You may never have heard of him, but the world we live in would be noticeably different if Cannon had never lived, or had made different choices. Ignazio Silone once said that the final conflict would be between the communists and the ex-communists. One less-than-final but still significant conflict today, that over the left's response to war, is between those who work and think along the lines that Cannon laid down and those - the inheritors, whether they know it or not, of Shachtman on the one hand and of Stalinism on the other - who don't. Without Cannon, there wouldn't be an antiwar movement. There would be a 'peace' movement, begging the warmakers to see sense. There would be a 'Decent left', cheering the warmakers on. And that - give or take a few fringe intransigents - would be that.

Cannon's deeds have prevailed all right. You may never have heard of him, but the world we live in would be noticeably different if Cannon had never lived, or had made different choices. Ignazio Silone once said that the final conflict would be between the communists and the ex-communists. One less-than-final but still significant conflict today, that over the left's response to war, is between those who work and think along the lines that Cannon laid down and those - the inheritors, whether they know it or not, of Shachtman on the one hand and of Stalinism on the other - who don't. Without Cannon, there wouldn't be an antiwar movement. There would be a 'peace' movement, begging the warmakers to see sense. There would be a 'Decent left', cheering the warmakers on. And that - give or take a few fringe intransigents - would be that.How did Cannon acquire the confidence that the cause for which he fought had 'social evolution' on its side? As a youth he walked into a meeting to hear a lecture on 'Marx and Darwin'. That lecture, and further study, convinced him 'theoretically - and that is the firmest conviction there is' that capitalism is inseparable from crises and wars, that the great majority of working people would sooner or later be compelled to move into action against these crises and wars, and that they would establish as capitalism's successor system one of global co-operation for abundance, peace, and freedom. 'The victory of Socialist America is already written in the stars.'

Nothing that has happened since his death in 1974 would have surprised him if he'd lived to see it, or disillusioned him. He had no illusions. Cannon's theoretical conviction allowed him to face unflinchingly the terrible realities of the 20th Century: World War, the rise of Stalinism, the Depression, the Yezhovschina, the Second World War, the Holocaust, the atomic bombings, the Stalinist labour camps, the Cold War and the colonial wars. Unlike some, he faced and fought them all while they happened, in real time. He never gave an inch.

We're all so much more sophisticated now.

Published on January 02, 2011 19:40

January 1, 2011

2011 - Year of Hope

It's all true, you know: Scottish writers do sometimes meet in a pub, where over a few pints we share our plans for world domination. We don't call ourselves the mafia for nothing, you know.

So I'm explaining the novel I'm writing and Ian Rankin says:

'Tell me Ken, is anyone writing a hopeful novel about the future?'

'That's my next,' I tell him.

It seems to be a trend. Charlie has a hopeful novel in the works, Alastair Reynolds has a whole series outlined, and I've heard the same question from some actual scientists.

One of the side-effects of writing a dystopian novel is that you start to look for the bright side, like that phone app that shows you what stars you're looking at and when you turn it towards the ground you see the sun on the other side of the Earth.

Happy New Year, everyone!

So I'm explaining the novel I'm writing and Ian Rankin says:

'Tell me Ken, is anyone writing a hopeful novel about the future?'

'That's my next,' I tell him.

It seems to be a trend. Charlie has a hopeful novel in the works, Alastair Reynolds has a whole series outlined, and I've heard the same question from some actual scientists.

One of the side-effects of writing a dystopian novel is that you start to look for the bright side, like that phone app that shows you what stars you're looking at and when you turn it towards the ground you see the sun on the other side of the Earth.

Happy New Year, everyone!

Published on January 01, 2011 10:18

December 10, 2010

Two odd visual effects

If you look at uneven snow (heaps thrown aside when clearing pathways is good, but a partially-melted smooth snow surface works too) through a vertical-horizontal grid, such as the fine wire one-centimetre mesh embedded in reinforced glass windows and doors, you may see the lumps and bumps as tilted blocks or pyramids.

If you look with one eye covered at a photograph with vivid colours and strong depth cues you may see it in 3D. The effect is quite unmistakable and was a complete surprise to me when I first noticed it. I was drinking coffee while reading New Scientist, and the raised mug got between the sightline of one eye and a picture on the page, and the picture suddenly sprang into a 3D image. I almost spilled the coffee.

These two effects may be well-known but I've never heard of them.

If you look with one eye covered at a photograph with vivid colours and strong depth cues you may see it in 3D. The effect is quite unmistakable and was a complete surprise to me when I first noticed it. I was drinking coffee while reading New Scientist, and the raised mug got between the sightline of one eye and a picture on the page, and the picture suddenly sprang into a 3D image. I almost spilled the coffee.

These two effects may be well-known but I've never heard of them.

Published on December 10, 2010 12:24

December 8, 2010

Notes towards a class analysis of the economic conjuncture

Published on December 08, 2010 13:04

December 7, 2010

If the Greenland ice sheet slides into the ocean ...

... as the mystics and statistics say it will, I predict I'll still be laughing at this picture, until I've paid my final power bill.

Published on December 07, 2010 18:12

December 5, 2010

Mark Bukumunhe interviews me at Novacon 40

Photographer, SF fan, and all-round nice guy Mark Bukumunhe interviewed me at Novacon last month, and the results are now here:

Also on Vimeo.

I do in fact lighten up a bit as the interview proceeeds. And in case anyone is wondering, the paperback of The Restoration Game is of course due out in April 2011, not 2010.

Also on Vimeo.

I do in fact lighten up a bit as the interview proceeeds. And in case anyone is wondering, the paperback of The Restoration Game is of course due out in April 2011, not 2010.

Published on December 05, 2010 18:15

November 30, 2010

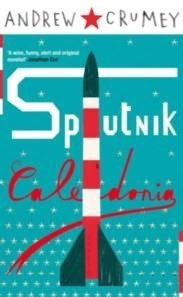

Sputnik Caledonia: or, the parallel worlds of SF and literary fiction

This isn't a review of Sputnik Caledonia, the very fine novel by Andrew Crumey, who chaired and spoke at the Newcastle Parallel Worlds event a couple of months ago. It's had some very good reviews already, and I have nothing but my own enthusiastic recommendation to add.

I'm just thinking about why it isn't SF.

An outline can make it look like SF. Here's a novel that starts in early-60s Scotland, in the life of an imaginative, space-and-SF-obsessed boy whose father is a factory worker, a socialist, self-taught and firmly opinionated. One subject the father holds forth on is the contingency of history. After some strange experiences hinting at alien contact, and after a sort of blackout, the boy finds himself a few years older, a young soldier, in an alternate Scotland which has become part of a communist-ruled socialist Britain in the course of the Second World War. He's a volunteer for a secret space programme, which is even more secretly preparing to contact an alien intelligence that has just entered the solar system. Intrigues, betrayals, contacts with dissidents, and an ascent into space follow, with an unexpected and satisfying ending that ties the strands together and enough unexplained to leave us thinking.

So, yes, it looks like SF. But it can't be read as SF.

For a start, the text denies us almost all of the specific pleasures of alternate history. It does eventually reveal the hinge on which history turned, and it's the only place where I heard an echo of an SF text, in a possible allusion to a specific incident and a general mood in Graham Dunstan Martin's Time-Slip. But it doesn't elaborate on this history. There's plenty of detail about daily life in this alternate socialist Britain, convincingly grim and shabby and riddled with secret privilege, but there's no time-line to reconstruct from planted clues, and hardly any figures from our history to recognise (ah-ha!) in new roles.

SF examples of all this abound, but to take another book published as mainstream: In Kingsley Amis's The Alteration, set in a 1970s world where the Reformation failed, there's some sly fun with a Cardinal Berlinguer, a Monsignor Sartre, and numerous other likewise impossible historical characters, and a purely SFnal delight in imagining subtle consequences.

Or, to lower the tone (and the bar) a lot: my novella The Human Front has some of the same themes as Sputnik Caledonia: Scotland, aliens, 1960s boyhood, alternate post WW2 history, socialism. It's a far slighter work than Crumey's in every way, but it has more of the above alternate-history tropes in its seventy pages than Sputnik Caledonia has in over five hundred, and it does more to rationalise its blatantly handwaved (flying saucers, come on) physics. Crumey could easily do that - he knows a hundred times more physics than I've ever forgotten - but he doesn't. He uses physics in a quite different way, as metaphor.

And that's the key. SF literalises metaphor. Literary fiction uses science as metaphor. In Sputnik Caledonia, the parallel world is a metaphor of what is lost in every choice. That's why the book is literary fiction and not SF, and is all the better for it. 'What might have been' functions in SF as a speculation. In Sputnik Caledonia, as in life, it's a reflection that we seldom have occasion to make without a sense of loss.

Published on November 30, 2010 19:45

November 29, 2010

Scotland at standstill as strange white substance falls from sky

Transport links across Scotland have been severely disrupted today by an overnight fall of an unknown substance from the atmosphere. Lying several centimetres deep over much of the country, it has made roads, railways and airport runways dangerously slippery and often impassable. As an emergency interim measure while authorities and scientists struggle to identify the phenomenon, schools have been closed.

The mystery material is initially white in colour, and is said to sometimes resemble salt. Attempts at closer comparison have failed because salt has - also overnight and unexpectedly - disappeared from all retail outlets.

Local sci-fi writer Ken MacLeod, who had to cancel plans to meet his daughter for lunch because of the transport chaos, blamed the lack of preparedness on 'cultural snobbery towards science fiction'.

'I'm not asking for some sort of instant readiness for anything,' he said. 'That would be utopian. But I do think that reading a few catastrophe novels or even watching the odd disaster movie on TV would open minds to the possibility of unprecedented events.'

A source at Edinburgh City Council accused the writer of having his head in the clouds. 'All we can do now is wait for the scientists to come up with something, which could take months. And keep watching the skies.'

Published on November 29, 2010 13:48

Ken MacLeod's Blog

- Ken MacLeod's profile

- 762 followers

Ken MacLeod isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.