Ken MacLeod's Blog, page 12

March 11, 2013

Only the truth is revolutionary

I'm inordinately proud to have an article with the above title in the current issue (#35) of Perspectives, the quarterly journal of Democratic Left Scotland. The article is about Thomas Kuhn's influential book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962). I think I've given a clear and fair summary of Kuhn's argument, and a brief account of the objections to it, some of which I share. Kuhn concludes that we can't say one paradigm is closer to the truth than another. Given that (e.g.) our space probes don't crash into crystal spheres, this strikes me as mistaken.

I'm inordinately proud to have an article with the above title in the current issue (#35) of Perspectives, the quarterly journal of Democratic Left Scotland. The article is about Thomas Kuhn's influential book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962). I think I've given a clear and fair summary of Kuhn's argument, and a brief account of the objections to it, some of which I share. Kuhn concludes that we can't say one paradigm is closer to the truth than another. Given that (e.g.) our space probes don't crash into crystal spheres, this strikes me as mistaken.Perspectives is an interesting and readable magazine of political and cultural discussion. In particular, it's one of the few places on the left where you can find a civilised and informed conversation about what's going on in Scotland in the run-up to the independence referendum. It has a fine pessimism of the intelligence, if perhaps a little less optimism of the will than I would like. To say that you don't agree with everything in it would be to miss and to make its point. Many of its back issues are available online. At £8 a year for a sub (£10 Europe, £12 rest of world), it's a steal.

Published on March 11, 2013 08:14

March 6, 2013

Re:Search

Some thoughts too inchoate to make a science fiction story from yet ...

This time next week I'll be attending and later blogging about the first afternoon of a symposium on The Evaporation of Things, which discusses the cultural and intellectual consequences of the digitisation and virtualisation of physical, and particularly of biological, objects. A couple of weeks ago, in a BBC programme on Google's attempt to digitise all written knowledge, someone was quoted as saying: 'Google isn't building a library - it's building an AI!' And today I read a much-tweeted piece on how Google Glass plus some existing/easily foreseeable applications and algorithms such as face recognition and voice recognition and speech-to-text transcription will make everything we say and do within sight of the damn things recordable and indexable and searchable forever.

The physical world is on its way to becoming as searchable as a database. As real-time surveillance from satellites and drones and sensors increases asymptotically to ubiquity, the knowledge won't even have to be recorded first. We'll be able to, as it were, google Earth.

Almost all recorded knowledge from the earliest bone-scratchings to your latest Tweet via the Library of Congress are all going to be in a single searchable virtual space.

Add to this that there is an uncountable number of deductions that could be made from what we already know, but that we haven't made -- or perhaps can't make in our heads, because they are of the type that Charles Dodgson identified long ago as 'pork chop problems', and which now look entirely soluble using modern symbolic logic and lots of computer power.

What seems to follow from this is that a large and growing part of the science of the future will be not finding new results but making new discoveries by connecting hitherto isolated drops in the ocean of facts we already know. The key skill will be formulating algorithms. Research becomes Re:Search.

Have I just discovered data mining, or is there something more here that we aren't thinking about yet?

This time next week I'll be attending and later blogging about the first afternoon of a symposium on The Evaporation of Things, which discusses the cultural and intellectual consequences of the digitisation and virtualisation of physical, and particularly of biological, objects. A couple of weeks ago, in a BBC programme on Google's attempt to digitise all written knowledge, someone was quoted as saying: 'Google isn't building a library - it's building an AI!' And today I read a much-tweeted piece on how Google Glass plus some existing/easily foreseeable applications and algorithms such as face recognition and voice recognition and speech-to-text transcription will make everything we say and do within sight of the damn things recordable and indexable and searchable forever.

The physical world is on its way to becoming as searchable as a database. As real-time surveillance from satellites and drones and sensors increases asymptotically to ubiquity, the knowledge won't even have to be recorded first. We'll be able to, as it were, google Earth.

Almost all recorded knowledge from the earliest bone-scratchings to your latest Tweet via the Library of Congress are all going to be in a single searchable virtual space.

Add to this that there is an uncountable number of deductions that could be made from what we already know, but that we haven't made -- or perhaps can't make in our heads, because they are of the type that Charles Dodgson identified long ago as 'pork chop problems', and which now look entirely soluble using modern symbolic logic and lots of computer power.

What seems to follow from this is that a large and growing part of the science of the future will be not finding new results but making new discoveries by connecting hitherto isolated drops in the ocean of facts we already know. The key skill will be formulating algorithms. Research becomes Re:Search.

Have I just discovered data mining, or is there something more here that we aren't thinking about yet?

Published on March 06, 2013 13:03

Intrusion out in paperback

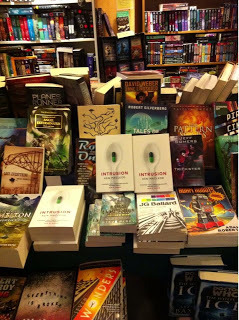

My 2012 novel Intrusion is now available in paperback. As you can see from my friend George Berger's photo of a display in the Uppsala English Bookshop, copies are already out in the wild and have made it as far as Sweden.

My 2012 novel Intrusion is now available in paperback. As you can see from my friend George Berger's photo of a display in the Uppsala English Bookshop, copies are already out in the wild and have made it as far as Sweden.I'm delighted, and honoured, that the book is on the Best Novel shortlist for the British Science Fiction Association's BSFA Awards:

Dark Eden by Chris Beckett (Corvus)

Empty Space: a Haunting by M. John Harrison (Gollancz)

Intrusion by Ken Macleod (Orbit)

Jack Glass by Adam Roberts (Gollancz)

2312 by Kim Stanley Robinson (Orbit)

In such company, it's an honour just to be nominated.

The novel is also on the Locus 2012 Recommended Reading List.

I'll finish with a quote from David Hebblethwaite's recent review:

[I]t is in MacLeod’s portrait of his future society that the novel shines most brightly. Several times, we see how the authorities cross-reference online traces and other seemingly-unremarkable points of data, and infer that someone might be a security risk – and the first they know of it is when the police come for them. This mirrors the novel’s sense that isolated bits of rhetoric have cohered invisibly to form the framework of government ideology; which can also be a net to trap the unwary, as Hope and other characters discover. The ending of Intrusion is also built on the idea of isolated details coming together unexpectedly, which is a satisfying touch.

Perhaps what’s most chilling about Intrusion is its quietness. As terrible as the society and events of MacLeod’s novel can be, its prose treats them largely as banal, which is quite fitting for the insidious way they’ve come about. Intrusion is likewise a book that creeps up on you – and stays there, just out of sight, waiting.

Published on March 06, 2013 02:49

January 14, 2013

Another train-wreck

The biggest left-of-Labour organization in Britain, the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), is in crisis over its leadership's handling of a rape allegation raised by a party member against a member of the Central Committee. A redacted transcript of a disaffected delegate's secret recording of the relevant session of the party's recent conference was leaked, and published online, with care taken to protect the identity of the complainant. Its substantial accuracy is not disputed. It leaves the SWP's credibility on the most sensitive questions of women's oppression severely compromised.

The biggest left-of-Labour organization in Britain, the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), is in crisis over its leadership's handling of a rape allegation raised by a party member against a member of the Central Committee. A redacted transcript of a disaffected delegate's secret recording of the relevant session of the party's recent conference was leaked, and published online, with care taken to protect the identity of the complainant. Its substantial accuracy is not disputed. It leaves the SWP's credibility on the most sensitive questions of women's oppression severely compromised.The panel that investigated the complaint and exonerated the accused was made up of five women and two men, most of whom had worked closely with the accused and all of whom had known him for years. As is painfully clear from the transcript, they all took their duty to be impartial with the utmost seriousness, despite its manifest impossibility. Why they nevertheless went ahead with the investigation is difficult to explain, at least in terms that make sense to anyone on the outside.

The debacle has now gone mainstream. It turns out that earlier outrage over how the case was being handled lies behind the formation of two declared opposition factions in the run-up to the conference. We learn that China Mieville, the well-known writer and a long-term party member, is aghast. The high-profile SWP blogger and author Richard Seymour is in open revolt. These and others have saved their own honour. Whether they can save that of their party remains to be seen.

The SWP has made plenty of enemies over the years, some of them on the left. I'm not among them, despite my often stated disagreement with much that the party thinks and does. All the more vehemently, then, should I say that this latest development leaves me sick. It was through the SWP's precursor that I made my first acquaintance with Marxism. The organisation's journal from the 60s and 70s shows an engagement with the real world that was, shall we say, not always obvious in some other parts of the left particularly at the time. I soon found my way, for better or worse, to a different tradition (and then another again). When the latter collapsed around me, and the world continued to burn, I joined the SWP for a couple of years in the early 90s. I made my disagreement with some of the party's most cherished verities clear before, during, and after my membership, and these disagreements have only deepened since. Never once did I face anything but argument. Others have had less happy experiences with the SWP. Its internal life and its way of relating to broader movements have left all too many people with lasting grudges. Maybe I was just lucky. Twenty years later, I still know, like, and respect people I met back then. I hope some of them are fighting against the disaster their party's leadership has brought down on their heads. Unless that fight succeeds, the party is done for.

Published on January 14, 2013 00:18

January 8, 2013

Above us only sky

Humanism is more terrifying than most humanists, I think, are willing to admit.

'Humanism,' wrote H. J. Blackham, 'proceeds from an assumption that man is on his own and this life is all and an assumption of responsibility for one's own life and for the life of mankind - an appraisal and an undertaking, two personal decisions. Less than this is never humanism.'

Coming from the first director of the British Humanist Association, and author of Humanism, the Pelican Original (1968) from which the above is taken, this seems authoritative enough. Challenging enough, too, when you think about its implications - which, of course, Blackham spent the rest of his fine book doing.

One that he missed is hidden in the phrase 'the life of mankind'. When we read that today, of course, we immediately politically correct it to 'the life of humanity', but we probably have much the same vague mental image as Blackham may have had in 1968, something like a blur of National Geographic pages flicking past, maybe the UN flag, the Earth from space, babies in Africa, suits in Manhattan, lab coats and microscopes ...

Whatever it is, it's wrong. Because 'the life of humanity' surely includes future humanity, and future humanity is much, much bigger than we think. Even if we never go out into space on any large scale, and merely send out machines to beam us solar energy, ward off asteroid impacts, and explore, and the human population stabilises at ten billion or so (or whatever anyone, Greens apart, considers a stable population) we're still talking about vast numbers of human lives over the next thousand years, or ten thousand, or hundred thousand, or million years ... and why stop there? Some species have survived almost unchanged for tens of millions of years. There's no reason in principle why we shouldn't be among them - or, if we aren't, having some cultural continuity with our successors. Nor is there any reason, in principle, for our civilization to collapse.

Taking responsibility for that is a big, scary deal. We're living in the very early days of human civilization. And that's just the start. If we relax the constraint of most of us staying on Earth, to imagine the future of humanity we have to go out on a clear night and look up.

Now try taking your proportionate particle of responsibility for that.

'Humanism,' wrote H. J. Blackham, 'proceeds from an assumption that man is on his own and this life is all and an assumption of responsibility for one's own life and for the life of mankind - an appraisal and an undertaking, two personal decisions. Less than this is never humanism.'

Coming from the first director of the British Humanist Association, and author of Humanism, the Pelican Original (1968) from which the above is taken, this seems authoritative enough. Challenging enough, too, when you think about its implications - which, of course, Blackham spent the rest of his fine book doing.

One that he missed is hidden in the phrase 'the life of mankind'. When we read that today, of course, we immediately politically correct it to 'the life of humanity', but we probably have much the same vague mental image as Blackham may have had in 1968, something like a blur of National Geographic pages flicking past, maybe the UN flag, the Earth from space, babies in Africa, suits in Manhattan, lab coats and microscopes ...

Whatever it is, it's wrong. Because 'the life of humanity' surely includes future humanity, and future humanity is much, much bigger than we think. Even if we never go out into space on any large scale, and merely send out machines to beam us solar energy, ward off asteroid impacts, and explore, and the human population stabilises at ten billion or so (or whatever anyone, Greens apart, considers a stable population) we're still talking about vast numbers of human lives over the next thousand years, or ten thousand, or hundred thousand, or million years ... and why stop there? Some species have survived almost unchanged for tens of millions of years. There's no reason in principle why we shouldn't be among them - or, if we aren't, having some cultural continuity with our successors. Nor is there any reason, in principle, for our civilization to collapse.

Taking responsibility for that is a big, scary deal. We're living in the very early days of human civilization. And that's just the start. If we relax the constraint of most of us staying on Earth, to imagine the future of humanity we have to go out on a clear night and look up.

Now try taking your proportionate particle of responsibility for that.

Published on January 08, 2013 12:05

January 5, 2013

Looking forward, looking back, and looking up

Intrusion has made four end-of-year best-SF lists: in the Telegraph, the Guardian, i09 and SciFiNow. The paperback is to be published in March.

Intrusion has made four end-of-year best-SF lists: in the Telegraph, the Guardian, i09 and SciFiNow. The paperback is to be published in March.Among the many satisfactions of Ken MacLeod’s fiction is his confidence in literature as a tool of political engagement. Intrusion (Orbit, £18.99) is a vision of life in a near-future Britain where nanny-state supervision has edged into soft-totalitarian surveillance and control. The plot revolves around an expectant mother seeking an exemption from the genetic “fix”, a single pill that guarantees a healthy foetus, but things get rapidly less cheerful from there in this steely, brilliant piece of work.

Also due out in March is a new US edition of my Sidewise Award-winning novella The Human Front, from the enterprising radical publisher PM Press. Like other volumes in the excellent Outspoken Authors series, this edition comes with additional goodies: an interview with me by Terry Bisson and a couple of of my short essays, one of them written specially for this book.

Also due out in March is a new US edition of my Sidewise Award-winning novella The Human Front, from the enterprising radical publisher PM Press. Like other volumes in the excellent Outspoken Authors series, this edition comes with additional goodies: an interview with me by Terry Bisson and a couple of of my short essays, one of them written specially for this book.Looking back ... The Human Front features flying saucers and revolution, as does the Engines of Light trilogy. Looking farther back, so did the very first SF novel I set out to write, in my mid-teens. The working title of that premature, immature and now mercifully lost effort was 'The End of Heaven'. I tried to inveigle Iain Banks and another friend into co-writing it. They (wisely) declined. Despite extensive background research, drawing on sources that ranged from Chariots of the Gods to Minimanual of the Urban Guerilla, the draft never amounted to more than a few closely-spaced pencilled pages. Some of it became part of the mulch from which my real first novel grew. It was in quixotic recognition of this that I inflicted on The Star Fraction the abandoned work's banal opening line: 'It was hot on the roof.'

The novel I'm working on, provisionally titled Descent, features a UFO encounter, albeit one that (even as a teenager, when it happens to him) the protagonist doesn't attribute to aliens. It also features a revolution, albeit one so peaceful and legal that most people don't notice it as such at the time. Unlike my previous stories, Descent takes on board the UFO experience as it exists in the real world, rather than elaborating an ironic rationalization of the UFO mythos. Part of its inspiration was a review in Fortean Times of Mark Pilkington's well-received Mirage Men, a book which I've since read and found very useful indeed. Pilkington shows that the story of a government cover-up of the truth about UFOs - the standard X-files trope - is itself a government creation, and is quite deliberately kept going by various governments and intelligence agencies.

You might think from all this that I'm fascinated by UFOs. I'm not. Pilkington's book was - with Neil Nixon's Pocket Essentials on UFOs - the second UFO book I've read in years. As a teenager I read everything on the subject I could find, and by taking everything at face value and trying to make it all fit together, learned that it was a mirage and a mare's nest. (The only SF book to do full justice to this aspect of the phenomenon is Ian Watson's Miracle Vistors, which captures exactly the escalating sense of unreality that takes over any attempt to make sense of it all.) I lost interest in the topic, but kept a vague suspicion that something beyond our present knowledge was behind it all. In my thirties I came across the standard sceptical treatments (starting with Ian Ridpath's classic article and found that there wasn't. Even now, I find myself surprised to learn how much some elements of the standard story - the MIB, for instance - were simply made up.

So like almost all SF writers - as taxi drivers everywhere discover to their astonishment - I'm a rock-ribbed sceptic about flying saucers and little green men. But I still write about them - in fact, off-hand I can't think of any other current SF writer (apart from those writing for film and television and franchises) who has written so much. Maybe Descent will at last get flying saucers and the coming revolution out of my system, but I make no promises.

Published on January 05, 2013 07:26

January 1, 2013

Happy New Year!

For the first time in far too many years we went to Edinburgh's Hogmanay Street Party, and had a great time. And for the first time in even longer, I'm having a New Year's Day without a hangover. (To avoid any unnecessary alarm, I hasten to add that I'm not ill and no, I didn't follow sensible drinking guidelines.) So, in another break with tradition I'll skip my usual reflections on the old year and hopeful or gloomy speculations on the new, and just wish everybody a happy and prosperous 2013.

Published on January 01, 2013 08:48

December 19, 2012

Never knowingly understated

It's not my place to review a book in which I have an essay, but it is my place to plug it. Unstated: Writers on Scottish Independence , just out from Word Power, is a book worth reading. Finely produced -- the type-setter is acknowledged among the contributors, as well she should be -- the book is an intriguing snapshot of what some Scottish writers think about the issue of Scotland:

We are deluged by facile arguments and factoids designed to 'manage' the Scottish question, or to rig the terrain on which it is contested. Before we get used to the parameters of a bogus debate, there must be room for more honest and nuanced thinking about what 'independence' means in and for Scottish culture. This book sets the question of independence within the more radical horizons which inform the work of 27 writers and activists based in Scotland. Standing adjacent to the official debate, it explores questions tactfully shirked or sub-ducted within the media narrative of the Yes/No campaigns, and opens a space in which the most difficult, most exciting prospects of statehood can be freely stated.Its declared intention, then, is to raise the level of the independence debate. Its immediate effect, predictably enough, has been to lower it further, with a somewhat uncharitable and highly selective reading of Alasdair Gray's contribution being met by a prickly response from Kevin Williamson and Mike Small. [Update: more here.] But that's only to be expected, and in the longer term the book bids fair to meet its publishers' hopes and vindicate its editor's efforts, undertaken 'for the sake of curiosity and in the interests of posterity'.

The current independence debate is -- beyond its widely deplored and even more widely indulged tetchiness, pettiness, and point-scoring -- a bit artificial and accidental. There's been no recent surge of sentiment for independence. Scotland is having an independence referendum in 2014 because the SNP won a quite unexpected majority of seats in the 2011 election to the Scottish Parliament, and was committed to calling a referendum if it had the power to do so.

The current independence debate is -- beyond its widely deplored and even more widely indulged tetchiness, pettiness, and point-scoring -- a bit artificial and accidental. There's been no recent surge of sentiment for independence. Scotland is having an independence referendum in 2014 because the SNP won a quite unexpected majority of seats in the 2011 election to the Scottish Parliament, and was committed to calling a referendum if it had the power to do so. More than likely, the SNP never expected to have to deliver on this so soon: the electoral system was set up more or less deliberately to prevent any one party being able to govern on its own, and in any coalition negotiations the referendum plank would have been the first and easiest to break. As it is, they're stuck with a massive distraction from the job that made most of their supporters in the 2011 election vote for them in the first place: being a fairly popular and competent governing party in the devolved parliament.

But you play the hand you're dealt. To have the future of the state a topic at all is something. Unstated is an attempt to seize the opportunity for a serious conversation about what kind of society we want. It's not in itself that conversation: each of the contributors wrote without knowing what the others were saying, or indeed who they were. No claim is made that the 27 authors represent anyone but themselves.

That said, it seems to me a fair enough sample of Scottish literary life. Of the 27, I counted 15 who would give a definite Yes to independence. Only two of the others -- Jenni Calder and myself -- give a definite No. The rest I've marked as ambiguous, or answering a different question. (The splendidly cross-purposed contributions of Douglas Dunn, Tom Leonard and Don Paterson are in themselves worth the price of the book.)

On this reckoning, a majority of writers here would vote for independence, and most if not all of these would hold out for a more radical polity and settlement than that offered by the SNP. (As would, I think, most of those ambivalent or against.) This distribution of opinions is pretty much the exact inverse of where the wider public stands at the moment. Whether this indicates that the writers sampled are ahead of the curve or just out of step remains to be seen.

Published on December 19, 2012 03:29

December 12, 2012

'in the English-speaking countries the word "poetry" would disperse a crowd quicker than a fire-hose.'

Orwell must have been wrong about that, or things have changed. The crowd for the launch of Where Rockets Burn Through filled the venue and stayed there, and everyone had a good time. Skiffy-themed cup-cakes on the table and an emergency bag of breathable air and space-ration sweets on every seat were part of the package.

Chris Scott has a fine photo collection here. Thanks to Napier University's social media team, you can see and hear me declaiming two poems here.

There's still time to get a copy to all your friends for Christmas, at a seasonal discount of 20% off.

Chris Scott has a fine photo collection here. Thanks to Napier University's social media team, you can see and hear me declaiming two poems here.

There's still time to get a copy to all your friends for Christmas, at a seasonal discount of 20% off.

Published on December 12, 2012 12:52

November 21, 2012

Yet another event

Most of my recent blog posts have been about upcoming events or articles published elsewhere. I hope to redress this fairly soon. Meanwhile, here's another.

The Scottish Book Trust's imminent Book Week Scotland includes a Pop Up Festival on December 1st at the Mitchell Library in Glasgow, featuring among much else me and Iain Banks, in conversation with Stuart Kelly.

The Scottish Book Trust's imminent Book Week Scotland includes a Pop Up Festival on December 1st at the Mitchell Library in Glasgow, featuring among much else me and Iain Banks, in conversation with Stuart Kelly.

An hour of fascinating conversation featuring Banks’ dazzling new Culture novel, The Hydrogen Sonata, and Ken MacLeod’s Intrusion, a clever, frightening and dystopian vision of the future that has drawn comparison with Orwell’s 1984. Chaired by Stuart Kelly.Even if you've already seen the well-known Banks and MacLeod double act - usually involving incomprehensibly inconsistent recollections of every significant event in our closely linked literary lives and long personal friendship - you'll see something new as we are publicly dissected by Stuart Kelly, the best-read man in Scotland and a dab hand with the scalpel.

This event is part of Scottish Book Trust’s day of celebrations at The Mitchell Library on Saturday 1st December.

Published on November 21, 2012 22:46

Ken MacLeod's Blog

- Ken MacLeod's profile

- 762 followers

Ken MacLeod isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.