Sarah Byrn Rickman's Blog, page 7

July 30, 2020

My Mentor and Friend Nancy Batson Crews, Part 2

Continued from last week: “We’ll get your interviews with the remaining WAFS,” Nancy Crews told me at the end of last Friday’s blog. “We’ll have a reunion in Birmingham. How soon are you available?”

This was a woman who, over the previous 15 years, built a successful real estate venture on land she inherited from her father. Before that, she ran a glider-towing business in the California high desert. She raised three children. As a young woman, she flew the Army’s fastest World War II aircraft. This woman finished what she started, and she did it with style.

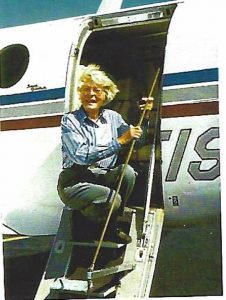

And at 79, Nancy qualified to fly copilot for her corporate pilot friend Chris in a King Air turbo jet. (See photo left.)

Nancy fixed me with her keen gray aviator’s eyes and waited.

“L-let me check my calendar,” I stammered

Getting Acquainted at the ‘Whistle Stop Cafe’

She made it happen! Four weeks later, I met “BJ” Erickson London, Teresa James, Gertrude Meserve LeValley, Florene Miller Watson, and Barbara Poole Shoemaker. Those five WAFS, Nancy and I were having lunch at The Irondale Café in Birmingham and getting acquainted.

The Irondale Café is famous. Birmingham native Fannie Flagg wrote about it in Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Café. Fannie’s aunt Bess Fortenberry once owned the café. And talk about a coincidence, while the WAFS and I were there, Fannie called the current owner to chat. When the famous author heard who was dining there, she picked up our tab!

I was still getting used to the realization that I now had access to the Originals. I listened, transfixed, to their stories. Over time, I earned their trust. I had to pinch myself to make sure it was real. I videoed my interviews with all six. Those films, today, are part of my 23 minute-WAFS documentary “Six WAFS Up Close and Personal.”

WASP Archive and In-Person Visits Yield More Stories

Back home in Ohio with the beginning of my story in hand, I managed some necessary traveling — sandwiched between my freelance newsletter jobs. I visited the WASP Archive at Texas Woman’s University. TWU is Mecca for WASP scholars. I managed a week in Florida. More interviews with Teresa James, a key player in my coming book.

Through Nancy, I received an introduction to Nancy Love’s daughters, followed by an invitation to visit them in Virginia. I learned about their extraordinary mother — the woman who birthed the idea of the WAFS back in 1940.

I had worked on The Originals: The Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron of World War II a year when, June 2000, Nancy was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer.

My agent, Liz, was trying to sell The Originals to New York. “Great story, but we can’t sell it in today’s market,” was New York’s response. Liz was ready to start the rounds of the mid-sized presses.—We didn’t have time.

The Grim Reaper Pursues The Originals’ Angel

“I’ll pay the printing costs,” Nancy said. Liz and her husband Greg, the publishers, went to work. The specter of the Grim Reaper pursued Nancy across every page I wrote.

I made three trips to Birmingham between June and November 2000 to work with Nancy. I watched her health deteriorate, but never her spirit. Incredible strength of character and the will to see the book through were Nancy’s trump suits. Doctor Jim, her physician and personal friend; Chris, the corporate pilot who tapped Nancy to be her copilot; and I, her hand-picked storyteller, helped cheerlead.

“Now we know an airplane’s not gonna get me,” she quipped.

I returned in December for my fourth visit. I met her son, Paul, who came to be her caregiver. The three of us talked a lot. Nancy approved the finished manuscript on December 22, 2000. She gave me, and the book, her blessing.

The Book’s Fate Was Totally in My Hands

The next day, I left to drive home. Nancy and I both knew it was our last meeting. She died January 13, 2001.

I had to finish the job without her. The Originals: The Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron of World War II was published July 2001. The story of Nancy Love’s original WAFS was, at last, told. Nancy Crews’ wish fulfilled.

In 2008, I made good on the rest of my promise to Nancy Crews when the University of North Texas Press published Nancy Love and the WASP Ferry Pilots of World War II. The following year, 2009, the University of Alabama Press published Nancy Batson Crews: Alabama’s First Lady of Flight. I had told my mentor’s story as well.

The following year, 2009, the University of Alabama Press published Nancy Batson Crews: Alabama’s First Lady of Flight. I had told my mentor’s story as well.

I’ve added six more books about the women who flew in World War II. My first WASP novel, Flight from Fear (2002), was followed in 2014 by Flight to Destiny (fiction based on the original WAFS’ story). WASP of the Ferry Command and Finding Dorothy Scott: Letters of a WASP Pilot were published in 2016. In March 2018, we released my first Young Adult-focused WASP biography—BJ Erickson, WASP Pilot. Nancy Love: WASP Pilot, another YA-effort, followed in 2019. Number 10 is coming October 15.

The Originals—Where It All Begins—the Best Seller

The Originals outsells them all—the 4,000 copies Nancy ordered are gone.—And why not? It IS the beginning of the story. I released a second, updated edition on September 10, 2017— the 75th anniversary of the founding of the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron.

Nancy Batson Crews dramatically changed my life. She made possible my crowning career achievements. She helped me fulfill my dream. None of what has happened to me since 1999 would have taken place had it not been for her faith and trust in me. She was, and is, my inspiration.

The last thing she asked me to do for her was to send a copy of the finished book to Fannie Flagg, to  thank her for our lunch. When the books arrived July 2001, I did as Nancy asked.

thank her for our lunch. When the books arrived July 2001, I did as Nancy asked.

In Loving Memory: Nancy Batson, Teresa James, and BJ Erickson

Fast forward to 2013. A local librarian friend called me. She had heard Fannie Flagg on the radio talking about her new book: The All-Girl Filling Station’s Last Reunion. The WASP were in it, she said, and Fannie told how she had learned about the WASP from this book The Originals.

The library’s copy of Fannie’s new book was waiting for me at the circulation desk. On the back page is this inscription: Written in loving memory of Nancy Batson Crews, Teresa James, and B.J. Erickson, and all the other WASP who came to the aid of their country in a time of need. — Fannie Flagg.

From left: BJ, Gertrude, Nancy, Florene, Teresa, Barbara.

Buy The Originals

https://www.amazon.com/s?k=The+Originals%3A+The+Women%27s+Auxiliary+Ferrying+Squadron+of+WWII&i

Buy Nancy Love and the WASP Ferry Pilots of WWII

https://www.amazon.com/s?k=Nancy+Love+and+the+WASP+Pilots+of+World+War+II&i=stripbooks

The post My Mentor and Friend Nancy Batson Crews, Part 2 appeared first on Sarah Byrn Rickman.

July 23, 2020

My Friend, WAFS Nancy Batson Crews

Nancy Batson Crews, WAFS pilot in World War II, and I met January 12, 1992. WASP Nadine Nagle and I picked her up at the Dayton Airport that evening. That meeting changed my life.

Nancy Batson Crews, WAFS pilot in World War II, and I met January 12, 1992. WASP Nadine Nagle and I picked her up at the Dayton Airport that evening. That meeting changed my life.

In January 1990, I went to work as a communications consultant for the International Women’s Air and Space Museum (IWASM), then located two blocks from my home in Centerville, Ohio. [IWASM is now located in Cleveland, OH] The fledgling museum was a repository for papers, photos, and memorabilia of the early women pilots of Amelia Earhart’s era and those who came after.

Joan Hrubec, IWASM Administrator, hired me. My first assignment was to interview Nadine — my first WASP — about whom I wrote in last week’s Blog.

IWASM Invites Pioneer Women Pilots to Speak

That fall, I helped IWASM launch a series of programs featuring pioneer women pilots to be aired for the cable television viewers in south suburban Dayton, Ohio. We videotaped the women—sometimes panels, sometimes single speakers—before a live audience. We recorded their voices, images, and their stories for posterity—a form of oral history.

Joan and I worked with the Miami Valley Cable Council to produce these programs on MVCC’s community-access channel. Between November 1990 and March 1994 we taped an even dozen programs that, to this day, still air via South Dayton’s Community Access Channel.

Knowing that, in 1992, the WASP were coming up on the fiftieth anniversary of their founding, Joan and I decided to put together a WASP panel. We asked Nadine to moderate the program and nearby Springfield, Ohio, resident WASP and museum supporter, Caro Bayley Bosca, to be one of the panelists. Caro brought in two more WASP, her best buddies from WWII Kaddy Landry Steele and Emma Coulter Ware. Joan invited nearby Ft. Wayne, Indiana, WASPs Marty Wyall and Margaret Ringenberg, as well as Anne Madden, a museum trustee from back east.

Nancy Agrees to Come From Alabama

I suggested Nancy as the panel’s representative original WAFS. I had just read about her in Sally Van Wagenen Keil’s book about the WASP, Those Wonderful Women in Their Flying Machines. What Keil wrote about Nancy assured me that she would be a delight to have on our program. Nancy’s desire to tell the WAFS’ story prompted her to say “yes,” she would join us. Nadine and I met her at the airport.

The taping was scheduled for Monday evening, January 13. It was a huge success.

As I got to know Nancy over the next two days, I was entranced. What I learned from her was that the few existing WASP books available at that time told only part of the story. The surviving WAFS, she said, felt that their very different beginnings and service needed to be told in a separate account.

Nancy Love and Her 27 WAFS Were the First

The familiar story of the 1,074 women who earned their wings through Army training in Texas is actually Part Two. Part One is the story of Nancy Love and her twenty-seven professional women pilots who went straight into the Ferrying Division to ferry trainer airplanes the fall of 1942. They were not military, rather, thy were civil service employees.

Nancy and I agreed to stay in touch.

I left the museum in 1994 to earn my Master’s Degree in Creative Writing. With 20-plus years of journalism under my belt, I wanted to return to my first love, fiction writing. I earned my degree in 1996.

By 1999, I had written three novels. The first I wrote with a friend, a mystery novel — The Woman in Wax. Not bad for a first novel, but sadly it is still in the drawer. My second novel was Quilted Lives, my thesis for my Masters.

Masters Focus: Southern Women Writers and Suffrage

Quilted Lives is a three-generational story set in Middle Tennessee, where I was born. I placed my first-generation heroine—the grandmother—in the midst of the Suffrage Movement in the South. Why? Because Tennessee was THE state that cast the final vote FOR the 19th amendment—Woman Suffrage—in 1920.

Nancy and I renewed our friendship in 1999 when she came back to Dayton for the reunion of The Wilmington Warriors, the men AND women pilots who ferried aircraft out of New Castle Army Air Base, Wilmington, Delaware, for the Air Transport Command. The WAFS (later called WASP) squadron was an integral part of that.

One Pilot Told Me About His Trip ‘Over the Hump’

Again, Nancy and I hit it off. She took me to the reunion gathering so I could meet the guys she flew with. One of them told me about one of his scariest flights “over the Hump.” He was talking about the route over the Himalayans that the male ferry pilots flew to get supplies from India to Kunming, China. That airlift help keep China in the war. Fascinating!

Back at the hotel having a late dinner in the bar, I gathered up my nerve and asked Nancy the question I wanted so badly to ask, but was afraid to ask. Would she let me write her biography? She looked at me thoughtfully. “No, Sayrah, [that Alabama accent] I want you to write about Nancy Love and the WAFS.”

There it was. She had decided that I was the person to write that all important, but untold story.

“How,” I asked, flustered. I didn’t have the money to travel around the country and do interviews. And why would the surviving original WAFS even want to talk to me. By then they had been burned by other writers with big dreams and empty promises. And I was an unknown quantity.

Nancy proceeded to tell me how we would do it — and then she made it happen!

And that is next week’s blog post.

[Reminder: We celebrate the 100th anniversary of the passage of the Woman Suffrage amendment this coming August 18!]

Thank you for reading my blog. To see my books on the WAFS and WASP of WWII, please check out this link:

https://www.amazon.com/s?k=sarah+byrn+rickman&hvadid

The post My Friend, WAFS Nancy Batson Crews appeared first on Sarah Byrn Rickman.

July 17, 2020

Emily Warner, Pioneer Woman Airline Pilot, Flies West

Emily Hanrahan Howell Warner — born in Denver, Colorado,  October 30, 1939 — made history. The first female pilot hired by a major U.S. scheduled airline, Emily took her final flight west on July 3, 2020.

October 30, 1939 — made history. The first female pilot hired by a major U.S. scheduled airline, Emily took her final flight west on July 3, 2020.

Bea Khan Wilhite, former president of the Colorado Aviation Historical Society and Emily’s good friend, writes: “We never believe that anybody has ended life, and particularly for pilots. We believe they fly west, and they continued flying. Emily flew west July 3, and she will be missed and lovingly remembered.”

Captain Billy Walker, Emily’s longtime friend, echoed that: “She is now flying on a westerly heading no doubt enjoying the smooth air and a bright star to steer by.”

Emily Warner (left) and the author/blogger Sarah Byrn Rickman

“Do You Think I Could See the Cockpit?”

Emily took her first flight at 18. Becoming a stewardess piqued her interest, but she had never flown in an airplane. A friend recommended she take a flight to see if she actually liked flying. She took a roundtrip Frontier Airlines DC-3 flight, Denver to Gunnison and back. As the only passenger on the return flight, she asked the stewardess if she could see the cockpit.— In 1958, that was possible.— The captain invited Emily up front.

Emily was hooked. She wanted to fly the plane, not be the attendant.

First step, she earned her private pilot certificate. She didn’t stop there. She forged ahead and earned her commercial, instrument, multi-engine, and instructor ratings. Then she went for the big one, the Airline Transport Pilot rating — the coveted ATP. Over 15 years, she taught a lot of other pilots — male pilots — how to fly. She dreamed of flying airliners. Then one day, opportunity knocked.

Her friend Captain Walker relates how, first, she had to show she could handle — “hand fly” — the controls of one of the most difficult airliners in use in 1973.

But Could She Handle Engine Failure on Takeoff?

Walker writes: “The Convair 580 — a very powerful, twin-turbine powered, 53 passenger aircraft — was extremely heavy on the controls.” Emily climbed into the simulator. “Sophisticated for its time, the simulator was very real.” The test: could Emily handle the stiff controls? Could she demonstrate basic instrument flying with some emergency procedures thrown in. And … she would have to “fly the airplane” in the case of an engine failure on takeoff. *[See end of this post for the link to Captain Walker’s outstanding article on Emily.]

After multiple approaches, Captain Walker says that Emily was asked if she was ready to quit. “She probably was exhausted,” he added. But her answer was: “I’m ready for whatever you want to toss my way.” “If the truth were known,” he writes, “I think Emily wore THEM out!”

“From the get-go she handled her flying with savoir-faire along with the interaction of the instructor and captain monitoring her. They were impressed! Emily would not know how much until sometime later.”

Frontier Airlines Hired Emily on January 29, 1973

Three years later, on June 6, 1976, Emily became the first female airline captain. That same year, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. put her Frontier Airlines pilot uniform on display.

I [your blogger Sarah Byrn Rickman] had the pleasure of meeting Emily at a Women in Aviation conference. I was working with the International Women’s Air and Space Museum (IWASM) in Centerville, Ohio. On the spot, I asked Emily to be a guest speaker for one of our Women Aviation Pioneers programs. We taped the lectures before a live audience at the Miami Valley Cable Council (MVCC) in Centerville.

She said “yes.” I was thrilled!!! My boss, Joan Hrubec, Museum Administrator, was thrilled.

IWASM, from left: unidentified, Margie McDonald, Emily Warner, Joan Hrubec, Ann Cooper, Marcia Greenham

Emily ‘Wows’ the IWASM Lecture Crowd

We drew an impressive crowd that evening. I introduced Emily and she took it from there. She told us about her career, and she talked about the strides that women pilots had made since the mid-1970s when it was all just beginning. She had the audience in the palm of her hand. They loved her!

Emily graciously answered every question from the audience. They were her total captives for the evening. As for me, I’ve never forgotten that night and how privileged I felt to have met her. I have never lost that feeling. She’s one of the greats! Posted are two photos from the event.

After Frontier closed its doors in 1986, Emily flew for Continental, and then as a captain for UPS from 1988 to 1990. She joined the FAA back in Denver as an air carrier inspector in 1990, then as air crew manager for the United Air Lines Boeing 737-300/500 Fleet. She retired from the FAA in 2002. In her 42 years in aviation, Captain Emily amassed more than 21,000 flying hours.

Among Emily’s Many Honors and Awards

Longtime member of the Ninety-Nines, the International Organization of Women Pilots;

Charter member of ISA+21, the International Society of Women Airline Pilots;

1974: first woman to have membership in the Air Line Pilots Association;

1983: inducted into the Colorado Aviation Hall of Fame;

1992: inducted into the Women in Aviation International Pioneer Hall of Fame;

1993: installed in the International Forest of Friendship, Atchison, Kansas: Amelia Earhart’s birthplace;

1994: the Emily Howell Warner Aviation Education Resource Center was established in the Granby (CO) Public Library;

1994: Colorado Senate Resolution 94-29: Honoring Capt. Emily Warner for her achievements in aviation history;

2000: inducted into the Colorado Wings Over the Rockies Museum;

2001: inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame;

2014: inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame, National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, Dayton, Ohio.

RIP Emily! Blue skies, and tail winds!

*Link to Captain Billy Walker’s piece on Emily, below.

https://captainbillywalker.com/aviation-history-people/1206/

https://www.9news.com/article/news/hi...

IWASM is now located in Cleveland, Ohio: Burke Lakefront Airport.

From Sarah: Thank you for reading my Blog, and thank you for reading my books. Here’s the Amazon link to all nine: https://www.amazon.com/s?k=sarah+byrn+rickman

The post Emily Warner, Pioneer Woman Airline Pilot, Flies West appeared first on Sarah Byrn Rickman.

July 10, 2020

WASP I’ve Been Privileged to Know

Nadine Nagle, My WASP Friend

© 2020, Sarah Byrn Rickman

This is the first of a series of Blog Posts I plan to write about WASP have I met and had the pleasure of knowing personally.

The first was Nadine Nagle. She and I would go on to travel together frequently — to WASP reunions and other events. This was a natural because we both lived in Dayton, Ohio. With her, I began my journey with these incredible women, a journey that continues today.

We met in January 1990. Nadine was 72 then, and had the most  beautiful white hair I’d ever seen. Her face, her smile, her demeanor, her attitude toward life, all were as beautiful as her hair. This lovely woman had been a kindergarten teacher much of her adult life. No, she didn’t “look” like a pilot. But then what does a pilot look like?

beautiful white hair I’d ever seen. Her face, her smile, her demeanor, her attitude toward life, all were as beautiful as her hair. This lovely woman had been a kindergarten teacher much of her adult life. No, she didn’t “look” like a pilot. But then what does a pilot look like?

Nadine and Sarah, National Aviation Hall of Fame 2005

Nadine with AF Captain Kim Monroe at WASP Reunion, Sweetwater, Texas, 2000

Born and Raised in Kansas

Nadine Engler grew up on a farm outside Chapman, Kansas. She attended Emporia State Teacher’s College to earn her teaching certificate. “In those days we’d go two years, earn a Primary Certificate, and start teaching. I began teaching in Marion, Kansas, in 1940.”

While in college Nadine met Dale Canfield, also studying to be a teacher. They planned to marry, but their first teaching jobs separated them. He was in Western Kansas, she in Eastern Kansas. The December 7, 1941, surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, that brought America into World War II, changed their plans.

Rather than be drafted, Dale joined the Army Air Corps and was sent to pilot training in California. He and Nadine decided to marry in April 1942. Dale couldn’t get leave to come home, so Nadine took the train to California and they were married there.

Dale Qualified on the B-24

“From there, we were sent to Wichita. There, Dale qualified as a B-24 copilot. The fall of 1942, the Army posted his squadron to England with the Eighth Air Force. I accompanied him east on the train, saw him and his squadron off, then returned home to Chapman.”

Early January 1943, Dale died when his B-24 crashed while attempting to land back in England. The squadron had been on a raid over the German submarine pens on the northern coast of France. Nadine was devastated, but she had accepted a teaching job in Junction City beginning the second semester, a little over a week away. She went. Slowly, she began to put her life back together.

In March, she read a magazine article about a flight training school for women down in Texas. Famous racing pilot Jacqueline Cochran, who ran a cosmetic firm bearing her name, had started the school with the backing of the Army Air Forces Commanding General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold. Cochran was recruiting women to learn to fly “the Army way.” The article got Nadine’s attention.

“I Wanted to Fly in His Place”

“If my husband can’t fly for our country in time of war, I’ll fly in his place,” she vowed. She had never been in an airplane.

That summer, Nadine went to Wichita, worked in a dime store, saved her money and took flying lessons. “I didn’t sign another contract to teach. If I was called into the WASP, I wanted to be ready to go. That fall I stayed with a cousin in Topeka and continued flying. I took a job in a drugstore as a cashier.”

When she had her required 35 hours, Nadine wrote to Jackie Cochran seeking admittance to the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). She was accepted into class 44-W-9, which would begin in April 1944. The 44 represented her graduation year; the W stood for women; the 9 indicated that hers would be the ninth class to graduate in 1944.

“Though I wasn’t a natural born pilot, I acquired the skills to be a good pilot.”

Nadine Canfield Nagle

Nadine reported to the school in Sweetwater. She trained for seven intense months, passed all her flight checks, and graduated November 10, 1944.

Sent to South Plains AAF for Active Duty

Posted to South Plains Army Airfield, Lubbock, Texas, Nadine served on active duty for just under six weeks. The WASP were disbanded and sent home December 20, 1944. It is with great relish that Nadine tells the story of her most memorable flight.

“I was assigned to fly five non-flying officers to San Antonio in an AT-10 for a meeting. The AT-10 was a twin-engine plane with room for a crew of two, but I was the lone pilot.

“We flew down, they went to their meeting. Late afternoon they called and told me their meeting was lasting longer than expected. We’d have to take off later. I changed the ETA and re-checked the weather.

Back to Lubbock After Dark

“Well, by the time they got down to Operations it was late in the afternoon. This was November and, of course, the days were getting shorter. We were going to be flying at night. I double checked everything again … you know, just to be sure. Our night training at Sweetwater had been very thorough and I had not been scared doing it. Still, I was a little bit … not nervous, but very conscious of what I was doing.

“When we landed at Lubbock, the men filed out of the plane and each one said, ‘Thank you for the nice flight. Good night.’ I said, ‘Thank you. Good night.’

“But I’ve always said there were six prayers going up to Heaven that night.”

###

After WWII, Nadine married Frank Nagle, an Air Force pilot. They had four children, three boys and one girl.

Nadine Engler Canfield Nagle: October 25, 1918 – August 29, 2018.

She was two months shy of her 100th birthday. RIP, my good friend!

###

Thank you for reading my blog. I hope you will read some of my books about the WAFS and WASP pilots of WWII. Here’s the link to Amazon.

https://www.amazon.com/s?k=Sarah+Byrn&i

The post WASP I’ve Been Privileged to Know appeared first on Sarah Byrn Rickman.

July 3, 2020

Here’s a Quick WASP History for You

By Sarah Byrn Rickman, WASP author and historian

In 1942, as America struggled to arm itself for war, the leaders of the Army Air Forces (AAF) knew that airpower would be crucial to winning. However, we had but a fraction of the number of trained pilots we needed to fight this war. And those men already were assigned to combat-related duty.

By spring of 1942, the Army was desperate for pilots to deliver the newly built trainer aircraft that were rolling off the factory assembly lines. Those airplanes were badly needed at flight schools in the South where fledgling fighter and bomber pilots were in training. No pilots could be spared to deliver the trainers to the schools.

28 Top Women Pilots Volunteered

When finding men to fill these jobs proved problematic, 28 experienced civilian women pilots volunteered to take on those ferrying jobs. Recruited by Nancy Harkness Love, they formed the country’s first female squadron in September 1942. Their name? The Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron or WAFS. They flew for the Ferrying Division, Air Transport Command, USAAF.

Photo: Kneeling: Original WAFS Teresa James, Betty Gillies; standing Barbara Towne, Helen Richards, BJ Erickson.

Between November 1942 and December 1944, through the efforts of another woman pilot, Jacqueline Cochran, 1,074 more women were trained to fly “the Army way”. Their training began in Houston, then was moved to Sweetwater, TX. Graduates of the early classes were destined to fly with Nancy Love’s WAFS squadrons.

Later graduates were assigned—on an experimental basis—to see if women could perform any number of flight-related jobs for the Army. They relieved male pilots of what some termed “the dishwashing jobs” of flying — the jobs the men preferred not to do. The women wanted those jobs. They wanted to fly!

Women Pilots Released Male Pilots for Combat

The efforts of Love and Cochran released male pilots to be sent where they were most needed to fight the War. Women pilots went on to serve in a variety of jobs at more than 120 bases around the country.

In August 1943, the WAFS (by then there were more than 100 of them) and the women in training in Texas all became known as the WASP—Women Airforce Service Pilots. They were placed under Cochran’s  command. However, Nancy Love continued to lead the WASP of the Ferrying Division, Air Transport Command (ATC). She reported directly to General William H. Tunner.

command. However, Nancy Love continued to lead the WASP of the Ferrying Division, Air Transport Command (ATC). She reported directly to General William H. Tunner.

Photo: The Original WAFS wore the ATC wings.

Over two-plus years of service, the WASP, collectively, flew every aircraft in the Army’s World War II arsenal. In addition to ferrying, they towed gunnery targets, transported equipment and nonflying personnel. They flight-tested aircraft that had been repaired — before the men were allowed to fly them again — plus many other jobs.

The Women Proved They Could Fly!

By late 1943, training aircraft no longer were needed. The factories now turned out high-performance fighter aircraft, known as pursuits. These aircraft could protect four-engine bombers on long-range bombing runs over Germany. The more experienced of Nancy Love’s WASP ferry pilots went back to school to learn to fly those pursuits. Delivering single-engine, single-cockpit pursuit aircraft to the docks on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts for shipment abroad became THE top priority job of the women ferry pilots.

The men who championed Love and the WAFS were ATC commander General Harold George and the Ferrying Division’s Tunner. Army Air Forces Commanding General “Hap” Arnold supported and approved Cochran’s idea to train women pilots for many flying-related jobs.

But the U.S. Congress Said “No”

Arnold was revered by the U.S. Congress, which was known to give him everything he asked for to fight the war. But in June 1944, when he sought to officially designate his WASP as members of the United States military, Congress said “no.” Disgruntled male pilots had complained loudly that women were taking their jobs. The press took up the issue and it resulted in a nasty smear campaign. The women pilots remained civilians.

Like the men, WASP flew whatever they were asked to fly. Like the men, they dealt with balky aircraft, malfunctioning equipment and occasionally deadly crashes. Thirty-eight WASP died flying for their country. But the military took no responsibility for them. Classmates or squadron mates chipped in to ship their bodies’ home.

No Gold Star for the Grieving Family

Throughout the program, the WASP received no medical care and no insurance benefits. No Gold Star was placed in the family’s window if their daughter died flying for her country. No burial subsidy. No flag on the coffin. Militarization would have remedied those inequities, but it didn’t happen.

The WASP were disbanded on December 20, 1944, and sent home with no recognition. Victory was in sight. The War would be over in eight months. The female pilots were expendable.

These 1,102 Women Airforce Service Pilots flew wingtip to wingtip with their male counterparts and were vital to the war effort.

Thank you for reading my books about the Original WAFS and the WASP of WWII. You can find them here:

https://www.amazon.com/s?k=sarah+byrn+rickman

The post Here’s a Quick WASP History for You appeared first on Sarah Byrn Rickman.

June 26, 2020

Remembering My Father: A Magical Day

The Road Home

It was one of those sultry Middle-Tennessee-in-July days when you never really get dry after your shower. Your clothes stick to you like Saran Wrap to a bowl of leftovers.

Five of us sat silently in the air-cooled car — staring out the closed windows at the ditches choked with weeds and wildflowers, the green fields of the passing farms, the lush tree-covered hills to the east and west. I turned and looked at my father.

He sat in the backseat flanked by his two grandsons. His once tall, erect body was now bent and frail, testimony to the disease that was eating away his insides, his strength, his will, his very life.

When Did My Father Grow Old?

Thin arms hung from the striped, short sleeve sport shirt, the bony elbows white knobs against the blue velour-upholstered seat. Gray was a permanent trespasser through his thinning black hair. The skin was mottled and tissue-paper thin across his forehead and drawn about his cheekbones. His green eyes lacked the zest for life I remembered in their depths when he was younger.

But this morning there was a faint look of anticipation on his sallow face. He was going home.

The two-lane blacktop highway shimmered with freshly-poured asphalt and the center stripe glistened clean and white, except where an occasional errant tire had touched it — still wet — and smudged the paint like a child inadvertently breaches the carefully drawn lines in a coloring book. The road, no longer the narrow winding road he drove as a young man, led to my dad’s hometown.

For Just a Moment, Time Stood Still

I searched the fog of thirty years trying to remember a similar visit — so long ago. I was eight, the same age as the older of my two boys now seated with my father in the backseat.

It was sticky hot that day too, before air conditioning in cars. I sat in the front seat squeezed between my plump aunt and portly uncle. My mother and father and another aunt, all slender as reeds, rode in back of the vintage 1939 Cadillac. My uncle was the funeral director in the neighboring town and his jet black sedan was not only a sign of his respected status in the community, but of his dark but necessary profession.

In the humid air, the spicy aroma of the weeds and the cloying sweetness of the wildflowers rose out of the ditches and enveloped the car when it stopped. Crossing rusted iron bridges over low, slow-moving muddy creeks, the tires whined and sent a clacking noise echoing back from the slatted guard rails.

Goin’ to Visit Kin

On that summer Sunday, we were going to visit kin — great aunts and uncles and distant cousins I had never seen before. Cousins, of course, would be children like me. And the childhood anticipation of the unknown, meeting a new playmate with whom to romp through the fields, pet the horses or chase chickens through the yard, alternately induced flutters of excitement and the hollow fear of the unknown. Would my cousins like me?

I needn’t have worried. My cousins were old. In their thirties and forties. The great aunts and uncles were even older — older than my aunts and uncle and certainly older than my parents. People like that couldn’t be cousins. Cousins were giggly girls my age or handsome, sturdy young men who were in high school and as wise and as fun to be with as they were good looking.

Would You Like a ‘Co-Cola’?

I listened — bored — while the grownups talked endlessly about people I had never met. Someone offered me a “Co-cola” and I perked up hoping my mother wouldn’t frown and shake her head, reminding me that I had already had one today. Forbidden fruit, Coca Cola. Anything that tasted that good and tickled the tongue so pleasantly had to be innately wicked

… And now I was the mother. The people we had visited that day long ago were many years dead. And we five, riding in icy air conditioned comfort this day, were not going visiting. We were searching for our roots.

First stop — the graveyard. The pungent smell of boxwood hit me as we stepped from the cool car into the muggy air. In Tennessee, boxwood and cemeteries go together. I first noticed it when we buried my maternal grandmother. Since then, the heavy fragrance has spelled death for me. But now, in the company of my father, my sons and my husband, my childhood sense of foreboding disappeared. We were communing with our heritage.

We Found My Grandparents’ Stones

Names and dates etched in weathered stone became living people when my father told us what he remembered about those who lay buried beneath our feet. We found my grandparents’ stones. I recalled my first trip to this out-of-the-way town on Tennessee’s Highland Rim. It was the sultry August day we buried my grandad. I was 11 then. My grandmother was already gone. I never knew her.

Standing between his father’s and his grandfather’s graves, my father told us that, as a little boy, he lived across the street from his grandfather. A coveted cup of coffee, served by Grampa’s second wife, always awaited him there.

I could see him, slender, handsome, dark-haired, seeking haven from studies, from two sisters, maybe even from punishment for some real or imagined misdeed, and from the everyday existence of a young boy in the rural South. He and his grandfather talked about history and current events. My father loved history — to read it, to talk it. In the older man, my father found a kindred spirit. And vice versa.

My Dad, the Family’s Pride and Joy

A polite, well-behaved, rather serious young man, my dad was the family’s only boy — their pride and joy.

Once, he accompanied the family’s Negro cook to church. He was four and she was in charge of him that Sunday night. When the family didn’t return from the doin’s at the white Baptist Church when expected, she dressed my father in his Sunday best and the two of them walked to the evening service at the black Baptist Church down the road. He had a wonderful time. He was such a little gentleman, the congregation made a big to do over him.

My dad’s maternal grandfather owned a farm. My father loved to tell of his summers spent “farming.” His favorite tale was how he made two rather large, unusually shaped stacks of hay while the help were making several conventional stacks. A high wind came up that night and blew over all but his two. My mother, who was not into the joys of country life, snorted with amusement at that tale.

The Boys Treated to Soda Fountain ‘Co-Colas’

We left the graveyard and explored downtown, built like most small southern towns around a square with the county courthouse in the center. A cousin owned the drugstore on the square. We stopped in to visit and, while the boys devoured comic books and a “Co-cola,” we talked family. My personable salesman dad was in rare form.

Then we drove down West Main Street looking for the house where my dad grew up. He was in the front seat now, leaning forward against the seat belt, his eyes searching as we drove slowly down the street.

“There,” he said, pointing at the two-story white clapboard house on the right. We slowed and took in the great oak tree in the yard, the second story porch that ran the length of the front of the house. His gaze shifted to the smaller house across the street. “And that’s my grandfather’s house.”

We turned around and parked in front of the low iron fence that encircled the house that had been his grandfather’s. My dad looked longingly across the street at “his” house. A woman sat on the porch swing, reading a magazine. “Wait right here.” He got out of the car, crossed the street, walked up the walk for the first time in 51 years and spoke to the woman on the porch. We watched.

“She’ll Let Us See the Inside!”

Then he started back toward the car, his step — so slowed by age and illness — quicker, spryer than it had been in years. His face wore a broad smile, his green eyes danced with pleasure. “Come on,” he called to us, waving his thin hand, motioning for us to get out of the car. “This lady’s mother owns the house. She’ll let us see the inside.”

The boys scrambled out and ran to him, each one taking a hand. The three of them crossed the street, the boys, in their exuberance, pulling their grandfather along.

The welcome cool of central air greeted us as we crossed the threshold. We let our eyes adjust to the semi darkness after the brightness of outdoors. The past opened up as we looked around. The furnishings were vintage 1930s, not unlike what he remembered. My dad was at home.

Upstairs we saw his bedroom, his bookcases, the windows through which he could see across the street to Grampa’s. We saw his sisters’ rooms. Descending the staircase, he told us of his older sister’s wedding — held right there in the house. She walked down that very staircase on her father’s arm to wed the funeral director.

In the Shade of the Giant Elm

Later we stood outside in the shade of the giant elm tree with the smell of the now friendly boxwood all around. My dad and our hostess reminisced about people in the town—living and dead. He was reluctant to let that magic moment get away. Even with two young adoring boys pestering and pulling at him, he remained, as always, serene and unhurried, the gentleman scholar-historian reaffirming his roots.

With one last look, one last wave, we piled into the car and headed back to tell my mother, my uncle, but most particularly my two aunts what all we had done, had seen, had learned, had experienced.

He lived four more years, but I think, after that day, he was ready. And my sons, today, have a better understanding and appreciation of the man who used to tell them stories of when he was a boy their age — of stacking hay, of having coffee with grownups, and of long talks with his grandfather, a very long time ago

The post Remembering My Father: A Magical Day appeared first on Sarah Byrn Rickman.

June 13, 2020

1961: A Woman in Space?

Continued from last week — June 5 post

Dr. Randolph Lovelace now had 12 more women pilots who qualified for the testing the first seven male astronauts had undergone. The 12 joined with Jerrie Cobb in the program that came to be known as the Mercury 13.

Lovelace scheduled an advanced round of testing for the 13 women. Cobb aced her testing, but before the other women could follow her, politics and public opinion sidetracked any further discussion. September 1961, Lovelace was notified that any further testing was cancelled.

None of the Mercury 13 Flew in Space

But restrictions on women flying military aircraft began to change in the mid-1970s. Then in 1978, when NASA announced its new pool of astronaut candidates, six women were named. All were mission specialists, not pilots. One was a doctor, the others were scientists with different specialties. Sally Ride, who held a PhD. degree in physics — one of the six — was the first American woman to fly in space.

By then, American astronauts had walked on the Moon and space travel now meant Space Shuttle trips that orbited the earth. Two pilots carried several mission specialists aloft at a time. Women made these trips into space. But, as yet, no women Shuttle pilots had been selected from the growing pool of female military pilots.

Eileen Collins First Woman Shuttle Commander

In 1998, NASA selected Eileen Collins, an Air Force lieutenant colonel and a pilot, to be the first woman to command the space shuttle. Her flight launched July 23, 1999. It had been 40 years since Dr. Lovelace chose Jerrie Cobb as his first woman astronaut test candidate.

In 1998, NASA selected Eileen Collins, an Air Force lieutenant colonel and a pilot, to be the first woman to command the space shuttle. Her flight launched July 23, 1999. It had been 40 years since Dr. Lovelace chose Jerrie Cobb as his first woman astronaut test candidate.

Eileen invited the living members of the Mercury 13 group to watch her launch into space. Seven of the Mercury 13 were there at Cape Kennedy to send Eileen off in style: Jerrie Cobb and Sarah Gorelick Ratley were joined by Gene Nora Jessen, Wally Funk, Jerri Sloan Truhill, Myrtle Cagle and Bernice “B” Steadman.

After Mercury 13 for Sarah Ratley

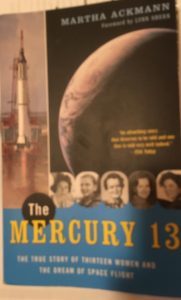

Summer 1961, when it appeared that the testing might continue, Sarah quit her job in order to fulfill her promise to Lovelace. Before the testing could begin in September, the program was cancelled. Politics and prejudice against women were the real reasons. To learn much more about this story, read The Mercury 13 by Martha Ackmann.

Summer 1961, when it appeared that the testing might continue, Sarah quit her job in order to fulfill her promise to Lovelace. Before the testing could begin in September, the program was cancelled. Politics and prejudice against women were the real reasons. To learn much more about this story, read The Mercury 13 by Martha Ackmann.

Already an accomplished pilot, Sarah said later of her Mercury 13 journey, “I was determined to pass and did not care how I did in relation to others. I reached for the stars.” Sarah thought she had a chance to explore new frontiers. As for the Mercury 13 she said, “someone must always lead the way so that others may follow their dreams. We went on with our lives.”

Sarah married and had a daughter, and she continued to fly. She flew in several more Powder Puff Derbies and in other women’s air races. She became an accountant and worked for the IRS. And with an eye to encouraging young women to consider careers in what we now call STEM—Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math—Sarah began to give talks about the thwarted Mercury 13 program and how to overcome disappointment and move on. The scientist became a communicator, and a good one at that.

Jerrie Cobb Never Stopped Flying.

Her professional flying career began early. She wasn’t even 20. On that 1952 ferrying flight to South America, Jerrie, then 21, and the man who hired her, Jack Ford, left Miami to deliver two AT-6 aircraft to Peru. They flew in formation. Jack tucked his plane up behind and just below Jerrie’s wing.

Her professional flying career began early. She wasn’t even 20. On that 1952 ferrying flight to South America, Jerrie, then 21, and the man who hired her, Jack Ford, left Miami to deliver two AT-6 aircraft to Peru. They flew in formation. Jack tucked his plane up behind and just below Jerrie’s wing.

This was Jerrie’s first flight over a long, seemingly unending expanse of water. Barring unforeseen trouble, they had enough fuel on board to make the flight safely. But Jerrie would be making more AT-6 deliveries to Peru, solo. Jack wanted her to get the feel of making the long flight for herself, so he gave her no further instructions.

The longest leg was from Kingston, Jamaica, to Barranquilla, Colombia, on the coast of South America. The range of their AT-6s was four hours to dry tanks. Their flight plan called for three hours and forty minutes. They had been flying more than three hours without a single check point to verify their position, winds or speed.

Jerrie Strained to See Signs of the Coastline

Well past their “point of no return” and committed to make Barranquilla or land in the ocean, Jerrie strained to see signs of the coast. Nothing.

Just as Jerrie’s fuel gauges neared zero, her low-frequency radio suddenly found a signal strong enough to home in on. The ADF (Automatic Direction Finder) needle swung up indicating the Barranquilla nondirectional radio beacon straight ahead.

Jerrie still saw nothing but ocean. Then she heard the button of Jack’s mike click on. He told her to look down. There she saw a line in the water separating muddy brown water from the blue-green Caribbean. The Magdalena River was flowing into the ocean draining the northern half of Colombia.

He told her to begin her gradual descent. The coastline would be visible within 15 minutes. They had made it!

And After Mercury 13?

After Mercury 13, the direction of Jerrie’s life totally changed. Earlier in her flying career, Jerrie had thought about becoming a missionary pilot. But, like the space program, the same lack of interest in women doing a job “meant for men” stymied her ambitions. After her brush with space, Jerrie once again became interested in the work of medical missionaries with the indigent people in the South American jungles. She returned to that dream. She would fly medicine, food and supplies to the these people. Flying was what mattered.

Information from Jerrie Cobb, Solo Pilot.

The post 1961: A Woman in Space? appeared first on Sarah Byrn Rickman.

June 4, 2020

1957: A Woman in Space?

In 1957, when the space race began, aviation was a man’s field.

On October 4, that year, the world was turned on its head, never to be the same again. The Russians launched Sputnik 1 and space flight was born. The 23-inch-in-diameter sphere with two sets of antennae and weighing 184 pounds was the first man-made object to orbit Earth. Sputnik was unmanned, but Russia’s dream, as well as America’s dream, was to put a man in space.

It crossed the minds of only a few that the first human in space could be a woman.

America Heads for Space

In answer to the Russians and Sputnik, in 1958, President Eisenhower created NASA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. NASA went to work. In April 1959, the space agency introduced America’s first seven astronauts, all military jet pilots — all men.

Dr. W. Randolph Lovelace, chairman of NASA’s Life Sciences Committee, and Air Force General Donald Flickinger together designed the medical and physical fitness testing for the astronaut candidates. The men went through the testing later in 1959. The tests were difficult, even for these pilots in top physical condition.

Dr. Lovelace specialized in aerospace medicine and believed that women would make excellent astronauts. They generally weighed less than men and were shorter, so they would need less oxygen and less food and water. He also thought they were more resistant to radiation, less prone to heart attacks and better suited to handling pain, heat, cold and loneliness. All were considerations when putting a manned object into orbit and returning it safely to earth.

A Woman in Space? Not a NASA Project

On their own, Lovelace and Flickinger decided to find out. This was not a NASA project.

In America, women pilots known as WASP (Women Airforce Service Pilots) had flown in World War II. But since the war’s end, women had been denied access to the cockpits of military airplanes. In 1957 only a handful of women were flying bigger aircraft and they were civilians.

Jerrie Cobb was one of them. She “realized that ‘higher, faster, and farther’ now meant something totally different since a satellite had been launched,” Martha Ackmann writes in her 2003 book The Mercury Thirteen. Jerrie recognized Sputnik meant humanity and flight were entering a new realm.

Cobb took her first flight at age 12 and earned her pilot’s license at 16. In 1952, she began ferrying aircraft internationally. Her first assignment was to deliver a USAF AT-6 military trainer aircraft to the Peruvian Air Force. [More about that in Part 2 next week!]

[Jerrie Cobb in the cockpit, with an aeronautical chart.]

Scientist/Pilot Also Recruited

Sarah Gorelick also caught the meaning of Sputnik. Sarah graduated from the University of Denver with a Bachelor of Science in Mathematics and minors in physics and chemistry. Long before today’s acronym, STEM, was coined, Sarah excelled in all four fields—Science, Technology, Engineering and Math. For today’s young women who want to specialize in STEM, Sarah proved an early role model. In her day, women were NOT encouraged to enter the technical world, but a few, like Sarah, did.

She began flying at age 15 and, like Cobb, became an accomplished pilot. Sarah was an electrical engineer with AT&T. By 1957, she had flown in five consecutive Powder Puff Derbies — the race more formally known as the All-Woman’s Transcontinental Air Race (AWTAR).

She began flying at age 15 and, like Cobb, became an accomplished pilot. Sarah was an electrical engineer with AT&T. By 1957, she had flown in five consecutive Powder Puff Derbies — the race more formally known as the All-Woman’s Transcontinental Air Race (AWTAR).

By 1960 these two, both 29-years-old, both accomplished pilots, held jobs women normally didn’t hold. And they were about to be tapped for the same experimental testing program the astronauts had just completed.

[Sarah Gorelick Ratley]

Jerrie & Sarah: the Right Stuff

Cobb was known in aviation circles. Dr. Lovelace wanted to test her. After the seven male astronauts completed their testing, it was Jerrie’s turn. Lovelace put her through the same regimen. Her results proved to be exceptional. She tested on par with the seven men. He and General Flickinger decided to test more female pilots.

They “wanted women who had racked up more than 1,000 hours in the air,” Ackmann points out. The two men sought Cobb’s input to find other qualified women.

Between January and August 1961, 18 women — all with more than 1,000 flight hours — underwent the testing regimen. Sarah Ratley arrived at Lovelace’s clinic in Albuquerque on June 19, 1961. She passed the grueling week-long program that tested her stamina, her grit, her ability to cope with long periods of solitude and — the worst one of all — the equilibrium test. For that, Sarah endured having ice water shot into her ear with a syringe.

She passed with flying colors. Sarah and 11 other women pilots qualified and joined Jerrie Cobb in the program that came to be known as the Mercury 13.

To be continued next week…

Footnotes:

Martha Ackmann, The Mercury 13: The True Story of Thirteen Women and the Dream of Space Flight. 2003: New York City, Random House, p.11.

Martha Ackmann, The Mercury 13, p.8

Martha Ackmann, The Mercury 13, p.72.

https://www.amazon.com/s?k=the+mercury+13+by+martha+ackmann

Jerrie Cobb photo courtesy the Ninety-Nines Museum of Women Pilots, Oklahoma City

Sarah Gorelick Ratley photo courtesy the International Women’s Air & Space Museum, Cleveland

The post 1957: A Woman in Space? appeared first on Sarah Byrn Rickman.

May 15, 2020

Check Out The Sale on Amazon Today – Flight to Destiny

To my readers out there. Today,  the Kindle edition of my second WASP novel — FLIGHT TO DESTINY — as an ‘on sale’ purchase: $2.99

the Kindle edition of my second WASP novel — FLIGHT TO DESTINY — as an ‘on sale’ purchase: $2.99

Please take a look!!!

Check out Amazon!

And THANK YOU for reading my WASP books!

SBR

The post Check Out The Sale on Amazon Today – Flight to Destiny appeared first on Sarah Byrn Rickman.

May 7, 2020

Yes, Mom Flew a Helicopter in the First Gulf War (Part 3)

“In Desert Storm, women were allowed to do combat support and combat service support,” Vicky Calhoun explained in last week’s Blog. “Then into the 1990s, the Air Force let women into fighter aircraft. That helped erode the Army argument that women couldn’t fly combat aircraft.

“Now women military pilots have flown combat aircraft—Apache and H-53 helicopters, A-10 Warthogs and F-16s—in the Second Gulf War and in Afghanistan.”

Vicky Calhoun wasn’t the first woman in an Army helicopter, though she was one of the earliest. How did she get along with the men with whom she flew?

“I Had 40 Fathers, They Took Care of Me”

“I once heard a woman speak on the four roles of women: daughter, wife, mother or sister. When I joined my Chinook unit in Germany, I was young, 24 years old. I was no threat to those seasoned men. The unit in Germany took me on as the daughter. I had 40 fathers. They taught me how to fly, and they took care of me.”

After serving 20 years, Calhoun opted for retirement in 2003, closing out her career as a lieutenant colonel assigned to the Pentagon. By then, most of the first wave of women military fliers had already retired, and now the second wave—Calhoun’s generation—was making the move as well.

In her second career, Calhoun became a government contractor, once again working almost exclusively with men. “I had the same struggles as a retiree that I did as a woman entering the military,” she said. “Proving myself. There aren’t many women doing this work.”

It’s been said the clothes make the man. Vicky Calhoun learned that, in her case, the clothes made the woman. And she learned that lesson well: “My uniform gave me credibility—my ribbons, my awards, my rank. All those things speak miles to people.

“I Had to Earn My Credibility All Over Again”

“I no longer wear a uniform. A woman in our culture has very little credibility when she walks in a room. Now I’m just another woman, not LTC Calhoun. The guys in my unit in the Army knew I would pull my weight. They trusted me. The corporate world is very different. It’s a new team and a new game. I started over, and I had to earn my credibility all over again.”

In April 2011, Calhoun joined the U.S. Army Cyber Command as a civilian employee. As Army Cyber organizations have evolved, today she belongs to the Cyber Center of Excellence. She is now involved in a new and different kind of combat: cyber warfare.

During flight school Calhoun joined the then fledgling Women Military Aviators (WMA) organization, formed in the early 1980s, when young women serving as military aviators needed a social and mentoring meeting ground. Seeking guidance, the new organization sought support from the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) of World War II—the first women to fly Army airplanes. Together the two organizations got the fledgling group off the ground. After retiring from active duty in 2003, Calhoun took command of the WMA, serving as its president until 2007.

You’re In the Chinook Cockpit With Her

This writer had the good fortune to meet Vicky during her tenure as WMA president. I was invited to do a presentation at their annual meeting about my research and books on the WASP — the women pilots who helped found WMA. There, I heard Vicky speak about flying her Chinook in Desert Storm. I was spellbound. I was there in that Chinook with her.

Hers was one of the most riveting talks I have ever heard.

Much to my dismay, I did not have a tape recorder with me that day and sorely regretted not being able to tape her outstanding presentation. It took a year or so, but we finally got together at a Women in Aviation conference in Nashville. Over coffee at a local Starbucks, we talked at length and I, always the reporter, got my story.

This three-part article is the result of her talk and of that interview, many years ago.

Twin Daughters Might Become Pilots Too

Yes, “Mom” did fly in Desert Storm. Vicky is the mother of twin daughters who are turning 13 this month.

Originally published in the March 2013 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.

To read parts 1 and 2, click here and here.

Sarah Byrn Rickman is the author of nine books about the WASP, with number ten due out later this year. She serves as editor of the official WASP newsletter. For more on the WMA, visit https://www.womenmilitaryaviators.com

Sarah Byrn Rickman is the author of nine books about the WASP, with number ten due out later this year. She serves as editor of the official WASP newsletter. For more on the WMA, visit https://www.womenmilitaryaviators.com

NEWS FLASH: Sarah’s most recent book, Nancy Love: WASP Pilot, is now available as an e-Book on Amazon. Check it out!

The post Yes, Mom Flew a Helicopter in the First Gulf War (Part 3) appeared first on Sarah Byrn Rickman.