Jane Rawson's Blog, page 11

June 23, 2014

What do you read when you’re all alone?

Hey there. I’m writing a pretty ridiculous article about toilet reading habits, and thought I’d introduce some scienciness by collecting responses to an entirely unscientific survey titled ‘what do you read in the toilet?’. This survey is, like, totes anonymous: I will not have even the vaguest idea who you are. So go on, fill it in, even if you don’t read in the toilet at all.

https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/YXCYJXM

June 17, 2014

When should you give up?

Before you get published, getting published is the most exciting thing that could ever possibly happen to you. And then when you get published, it is.

What being published is supposed to feel like.

Being published feels like the opening of a magical door. You’re in. You’re an author. Your book is in bookshops, it sits there in the same place as Middlemarch and Gilead and Infinite Jest and all those other BOOKS. You’ve been chosen. And it is, it’s magical for a bit. And then the bookshops send all the unsold copies back and that’s it. You’re not on the shelves anymore, no one will review you, no one will ask you to be on a panel at a literary festival. You thought you’d made it, but you didn’t realise that was just the first door. Now you can sit in the anteroom of the vestibule of the foyer for the rest of your life, while the real actual chosen keep opening doors and moving in and in and in.

What being published usually feels like.

I’ve read a few things over the last month or so which have made me realise what a tiny step towards being an author this getting published business is. First, there was this piece from author Annabel Smith about looking for an agent when you have two published novels and a third on the way. Basically, she says, it makes no difference that you’re published. Nothing has changed, it’s still the case that no one wants you; no one cares. If you haven’t sold big, you might as well have never been published. Other authors talked about how if you haven’t sold big, it might even be an impediment to have been published – all the data about your crappy sales lives on forever on BookScan, where prospective publishers can see it and decide you’re really not worth the risk.

Then I found out that Tom Flood won both the Vogel and the Miles Franklin for his 1988 novel, Oceana Fine, and then never had another novel published ever again (in the words of Wikipedia, he was ‘confined to short stories’, as though it were a punishment for wrongdoing).

And then there was my second royalty statement, which I got yesterday. My first one was OK, I guess. I made $1700 in the first six months my book was out. I got to buy a nice second-hand table, take a trip to the Adelaide Festival to see John Zorn and get my first tattoo at the improbable age of 44. I also subscribed to a bunch of Australian literary journals. So, y’know, that’s nice. I knew my second six-monthly statement would be smaller, but hoped it might buy me a ridiculously overpriced haircut & colour; that’s right, my huge ambition was to make $200. But no dice. Between December and May I sold minus 25 books. Who even knew that was possible?

I’m reminded of the wise words of ‘saying what everyone is thinking’ (perhaps not the author’s real name) who posted on a Wheeler Centre discussion about the lack of money to be made as a writer:

I’m going to address the elephant in the room. If you’ve done a fair bit of marketing and your book is not selling, then maybe you haven’t written a book that lots of people want to read. That’s not to say that you haven’t done your best. You just haven’t written a book that lots of people want to read. The world doesn’t owe you a living.

When A wrong turn at the Office of Unmade Lists was published, it turned my life around. Something in my brain shifted. I had permission to take my writing seriously. Suddenly I didn’t care so much that my career trajectory had been less than stellar, that I earned less than my friends and my peers, that I still, at the age of 44, had no real ambition for what I wanted to do when I grew up. I was an author. I could do whatever at work, because at home I was an author. In every spare minute I was an author. Look: I have a book: I am an author. And now, am I not? And what does that mean?

Like Annabel Smith says:

If my next grant application is unsuccessful I will need to return to teaching ESL at a local university. It is an enjoyable and well-paid job, but it is not the job I want to be doing. The job I want to be doing is writing. And aside from the financial implications of unsuccessful grant applications there is the horrible sense of being perpetually judged and found wanting, the feeling of competitiveness with other writers and the sensation of being always on tenterhooks while you await the outcome of some opportunity. Sometimes the grinding sense of being perpetually undervalued makes it hard to be gracious about the success of others; so that when I saw Graeme Simsion’s The Rosie Project on the shelves at Coles, instead of thinking ‘Good for him’ I felt like throwing myself onto the floor of aisle 3, screaming ‘Why can’t it be me?’

And I wonder if there is a point where you should decide, hey, you’re not really an author after all. That maybe it’s time to do that psychology masters you were once considering and get a real job. Or knuckle down at the day job and try to at least rise up the crappy publishing ladder to a managerial position. Because, let’s face it, I’m not really an author.

But at the same time, I am still a writer. That book that got published? I wrote that five years ago. Since then, I’ve written two more (incomplete) novels and god knows how many short stories. Really, nothing has changed. I wrote, I write, I will write. Fiona McFarlane, currently shortlisted for the Miles Franklin for her debut novel The Night Guest, puts it beautifully in this piece she wrote for the ABC:

There’s no doubt that being published and interviewed, appearing at festivals and on prize shortlists makes a difference to the way our work is perceived. The 29 years that elapsed between The Fake God [the first thing she wrote] and The Night Guest take shape because of the publication of the latter; before my first novel came out, I was still just someone trying to write a first novel. But I’m now just someone trying to write a second novel. I love the same books I always did; my fascinations run the same course; I’m still alone in a room with my brain. I don’t mean to sound ungrateful. It’s a privilege to be published, to be read…

I’m still alone in a room with my brain. Does it matter if no one wants to read what I write?

June 8, 2014

Passing the baton: a blog hops to Yvette Walker and Alex Landragin

Thanks so much to Yvette Walker – author of the utterly gorgeous, if you haven’t read it yet you should really get on with it ‘Letters to the End of Love’ – for joining in the ‘Writing process blog hop’.

You can read her entry at her Facebook page. Here’s a taster:

Every writer has different strengths and weaknesses. I am led by my characters who wander in like Ulysses, fresh from adventures unknown with stories to tell (which they don’t give up easily) and I’m grateful that they lead the way because I loathe a novel with underwritten characters and a plot straight out of a cereal packet. At some point in my hard slog working on my six major characters, it became clear I couldn’t avoid it any longer – I needed a plot.

Thank you also to the prolific Alex Landragin, author of the Daily Fiction Project, who is now writing a commercial masterpiece in the libraries of Paris. His entry is here. He says:

I want to create a jigsaw puzzle plot using an assortment of genres that are rarely combined in this particular way, because what I want to write isn’t so much fine writing as it is a mind-altering substance.

And thanks again to Annabel Smith for hooking us all into this process.

June 1, 2014

Can Climate Change Fiction Succeed Where Scientific Fact Has Failed?

Here’s me on the Wheeler Centre’s ‘Dailies’ page…

Last month, threeseparatescientific papers came to the same conclusion: the West Antarctic ice sheet is melting, and it’s too late for us to reverse the process. If you heard the news you’d have realised, at an intellectual level, that we’re in serious trouble and something needs to be done.

So what did you do? Did you quit your job and travel immediately to the Leard Forest Blockade to stop Australia’s massive coal exports? Did you call your bank and demand they pull all your money out of fossil fuels ? Did you move to New Zealand and buy a house a long way up a mountain? Maybe you did, but it’s more likely you felt awful for a bit, maybe even a day or two, then you got on with your life. I know I did.

There are two kinds of climate deniers. There is the small group of people who deny human behaviour is affecting the atmosphere in a way that is disrupting the climate. This group is beyond the reach of persuasion; their objection to accepting climate change is ideological, financial or both and facts don’t enter into it.

So let’s forget about those guys (and they mostly are guys) and focus on the much bigger group – the rest of us. We think humans are changing the climate, but live as though nothing could be further from the truth. Sure, we drive less, buy more efficient appliances and maybe even install solar panels, but it’s disproportionate to the size of the threat we face.

Read on here…

May 29, 2014

Living it up down the Great Ocean Road

Here’s a little article I wrote for Dwell Magazine about a super-fancy beach house down on the Great Ocean Road. It had the most comfortable armchair I’ve ever sat it in.

(A little weirdness was introduced in editing when the owners decided they’d rather not have their names published…)

May 27, 2014

Are you a gear-head?

I used to be a photographer, back in the days of film and paper and chemicals and darkrooms. I loved everything about taking, processing and printing images, but I couldn’t get excited about high-end cameras, light-meters and so on. I preferred keeping the instruments basic and using my eye and the darkroom to do the work. Once everything went digital and the gear – including Photoshop – became even more important, I lost interest. Same with music – I’ve always owned pretty crappy instruments, and when I record stuff it’s at the lowest end of lo-fi (and also appallingly executed).

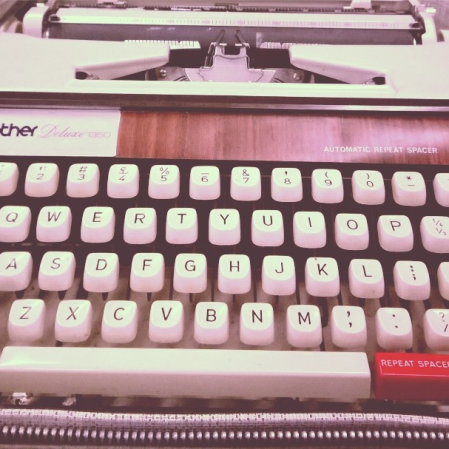

These days I’m a writer, and lately I’ve realised I’m always, at some level, searching for a piece of magic gear that will fix my problems. Usually it’s notebooks or pens. If I just had the perfect fine-point pen and some kind of ironically retro notebook, I know I could write a killer piece of literary fiction. This week I got a typewriter, because that’s going to make all the difference. And today I was wondering if I should start using Scrivener…

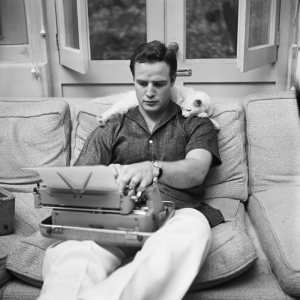

I’m pretty sure WG Sebald used one of these…

How about you? Are you waiting til you find the perfect implement before you start your next story?

May 25, 2014

My writing process – a blog hop

Thanks to blogger, tweeter and author extraordinaire Annabel Smith for nominating me for this round of the writing process blog hop. You can read about how she makes the magic happen here.

What am I working on now?

Last year I had a great idea: wouldn’t it be interesting to write a handbook to help people survive the ravages of climate change? Turns out, yes, it is interesting; it’s also really time-consuming, so not much in the way of fiction is getting written.

That said, this book on surviving climate change is going to be ace. I’m writing it with James Whitmore, Energy & Environment editor at my former employer, The Conversation. We want to find out how people can best make it through the unpredictable times to come: where they should live, what they should live in, what kind of food they should eat, the skills they’ll need, and how they’ll stay sane.

Unlike me, James isn’t scared of ringing up total strangers and asking stupid questions. So far we’ve chatted with a bloke building an Earthship in the Adelaide Hills, a guy who lived through the Black Saturday bushfires, the calmest survivalist ever (his next-door neighbour owns a military tank), and Alexis Wright, with many more thrilling interviews to come.

(OK, on the side I have been mucking about with a few fictional things. I’ve torn apart a novel I originally wrote in 2000 and rewritten it as a novella: it’s about the improbable tumble of coincidences set off when a woman’s severed arm is replaced by the transplanted limb of her unrequited lover’s wife. Good luck getting that published, right? And I’ve been tinkering around the edges of a novel I’ve been working on for the past few years: it’s the fictionalised story of my great-great-grandfather, who survived eight days on a shipwreck without water or food. As Richard Flanagan would say while munching on yellow kingfish pancetta, “You grow up knowing there is this sort of Homeric story all around you. You realise it speaks to a whole universe of feeling. Then you become a writer and it is the thing that, if you have the courage and ability, you would wish to write about. But it’s terrifying because it is so vast”. So like I said: tinkering around the edges.)

How does my work differ from other works in its genre?

I don’t know what genre I write in. It makes it hard to write pitches to publishers. I tried this ‘what genre is my novel?’ website, and it said I write feminist urban fantasy satire. I suspect that isn’t true.

At the risk of enraging Annabel Smith, who posits novels which are both speculative and literary are ‘few and far between’, I’m going to claim my genre is just that: literary speculative. Does that mean I don’t have to answer the question? I think my debut novel, A wrong turn at the Office of Unmade Lists, had more jokes than other writers in my genre (some might say too many jokes), and more bits that might make you cry. And a lot of plot twists without really very much action, which is pretty unusual for a novel the Aurealis Awards thought constituted science fiction.

Why do I write about what I do?

Most of the things I write seem to start out as a ‘what if?’ question I feel compelled to explore. What if the things you imagined then forgot lived lives of their own somewhere just outside yours? What if limb transplants came with all the dreams of their original owners? What if you divided America up into 25-foot squares and tried to stand in each of them? What if your identity was accidentally wiped from all central records? What if you survived a horrible shipwreck and psychology hadn’t been invented yet?

As to where those questions come from in the first place, the blame lies in this endlessly fascinating world – art, dreams, drunken conversations, accidents, the news, a scrap of paper on a train station, an argument about one thing that turns into an argument about another. There are too many questions for one person to answer.

How does my writing process work?

I write fiction and non-fiction differently. Does anyone care about non-fiction? No? I didn’t think so – ask me in the comments if you do.

How the pros do it (this photo doesn’t belong to me but I cannot find its copyright holder anywhere…)

With fiction, like I said, it usually starts out with a question I want to answer – I wrote a short story recently after Scott Morrison told asylum seekers on Manus not to ‘even dream of coming to Australia’; I wanted to know, what would happen if he actually tried to control asylum seekers’ dreams? I also collect stuff, all the time – scraps of overheard conversations, things I see in the paper, ideas that pop out of my head – just in case I need them later. Consequently a lot of what I write features either public transport or boring offices.

I don’t really plot. I’ve tried it, and so far I’ve always ditched the story once I’ve plotted it out – knowing where I’m going makes me bored. I do sometimes give myself a place to get to in each chunk of writing (‘by the end of this scene, Jerry should have found out why the shopping trolley is possessed’), and sometimes I give myself things I have to include in each chapter to keep me on some kind of track (one novel was based around a mix tape, one song for each chapter), but for the most part I just write, fast, and see what happens. I do like to get my characters into predicaments then agonise over how they’ll get out.

So yeah, first draft is fast and I try to write a lot and regularly – every day for a month, say. This has to fit in around a regular job, friends (luckily, two of them often write at the same time I do), husband, cooking dinner, cleaning, patting cats, playing music, watching footy and so on, so you can see why I have to write fast.

I have no idea how to rewrite. I really just don’t. One of my friends told me he throws away his first draft and writes a second without even looking at it again. I think he’s lying. I hate redrafting: hate, hate, hate it. It’s partly because I’d rather think I can write perfectly first go, and partly because reading what I’ve written is the same kind of agony you feel listening to yourself talking on tape*. It’s gross. The only thing I’ve found which works consistently for me is reading out loud, preferably to someone who’s prepared to listen and give feeback (thanks, husband). Reading out loud really reveals how stupid your writing is, and creates a desperate urge to fix it. I hear pretty much everyone else gets other people to read and critique their stuff, so I reckon I might give that a try next time around.

OK, enough; this is getting way too long. I’m handing over to the next two in the chain. Alex Landragin is the author of the gigantic online extravaganza, The Daily Fiction Project, and he’ll be posting his contribution here. Yvette Walker wrote the gorgeous and heartbreaking Letters to the End of Love and her update will appear here.

If you have any questions about any of this, I’d love to answer them. And I’d love to hear how people go about writing second, third and fourth drafts: I need help! (Also, plotting: is there a way to plot out a book without losing interest in telling the story?)

Enough writing

*Tape? Who records anything on tape anymore?

May 10, 2014

12 debut Australian and NZ authors with a promising future

12 debut Australian and NZ authors with a promising future

Lisa Hill from ANZ Lit Lovers has written a great round-up of 12 local first-time authors to try out. She has very kindly included ‘A wrong turn at the Office of Unmade Lists’ and it sits alongside some intriguing company, much of which I hadn’t heard of; “Wulf” is particularly tempting, and I really should get around to reading “The Roving Party”.

April 26, 2014

The power of doodles

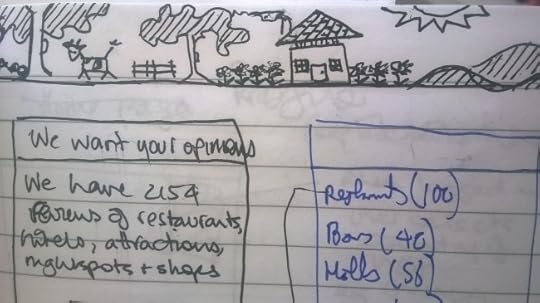

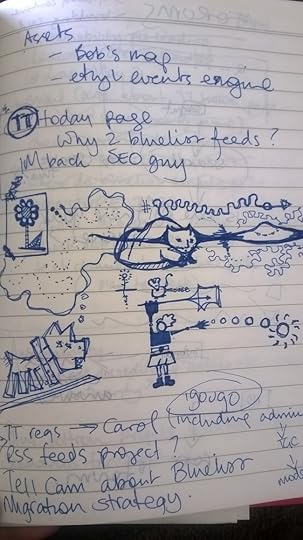

These were all in a work notebook from 2007, kept during the course of a project that went from bright hope to crumbled disaster. Tucked in the back of the book I found my resignation letter.

Thanks to @tinyowlworkshop for reminding me I can’t concentrate without doodling.

April 23, 2014

Why would a writer ever get any better?

Dan Foy

A week or so back I got into a twitter discussion about whether any authors are any good late in life. Many people felt like a writer’s middle years are their best,and that most make a slow (or rapid) decline into irrelevance. But offsetting age and the loss of faculties, most felt,was that your ‘craft’ would grow and develop.

I’ve always kind of blindly assumed this: that as I kept writing I’d get better at writing. That of course my third novel would be better than my first, because that’s what happens, right?

But I’ve just started wondering why that would be the case. Why should anyone learn anything about writing just from writing? It’s not like you get much feedback. A swift edit, perhaps, from an overworked and underfunded publisher. Maybe a few short reviews here and there that might or might not give you some useful feedback. Writing, for most people, is an entirely solitary pursuit without teachers or even peers to push you to better things (unless you’re the kind of writer who seeks that out).

So why should you get better? Is there anything essential about writing itself that causes someone to get better at it?