Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2455

January 5, 2011

Biting the Bullet on Majority Rule

Ruth Marcus says filibuster reformers should watch what we wish for:

There is a way around this, but it opens a parliamentary Pandora's box. If Democrats succeed in establishing that the rules are open for change by majority vote, what happens if Republicans win a Senate majority in 2012? Democrats have 23 seats to defend that year compared with 10 for Republicans. Anyone want to bet the mortgage money on the outcome?

Imagine the start of the 113th Congress in January 2013. House Speaker John Boehner's first act, once again, is to repeal what he calls "Obamacare." Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, invoking the Udall precedent, moves to change the rules to eliminate the filibuster, and his caucus – over howls from the Democratic minority – agrees. The Republican Senate then votes to repeal the health-care bill, which is promptly signed . . . by President Palin.

This is the most frequent objection I hear to Senator Udall's proposal, but I don't think it makes sense. The 113th Senate will change the rules to adopt a majority voting procedure if and only if a majority of members of the 113th Senate want to adopt a majority voting procedure. Republicans in the 109th Senate seriously considered doing this, but chose not to do so because supermajority voting is in the interests of Senators qua individuals. The 111th Senate didn't even seriously consider making the switch, because supermajority voting is in the interests of Senators qua individuals. The 112th Senate is considering rule changes, but has dismissed majority voting out of hand because supermajority voting is in the interests of Senators qua individuals. The rules will be changed when partisanship and ideological fervor override considerations of egomania and vainglory. What the 112th Senate does is going to be irrelevant.

Of course the larger issue here is that if some future incarnation of Mitch McConnell does implement a majority voting procedure, that would be a good thing. It doesn't take 60% to win a Senate seat, it doesn't take 60% to win a Supreme Court case, it doesn't take 60% to pass a bill in the Canadian parliament or the German one or the Dutch one. Counting how many members favor a measure versus how many oppose it and letting the side with the larger number carry the day is a very excellent way of conducting a vote.

Taxing the New Elite

Chrystia Freeland's profile slash condemnation of "the new global elite" is a ton of fun. This is the only part I have much to say about in terms of substantive policy journalism:

What is more striking is the degree to which even former Obama supporters in the financial industry have turned against the president and his party. A Wall Street investor who is a passionate Democrat recounted to me his bitter exchange with a Democratic leader in Congress who is involved in the tax-reform effort. "Screw you," he told the lawmaker. "Even if you change the legislation, the government won't get a single penny more from me in taxes. I'll put my money into my foundation and spend it on good causes. My money isn't going to be wasted in your deficit sinkhole."

What's telling here is the dissonance. On the one hand, the princes of Wall Street are upset at the idea of needing to pay higher taxes ("screw you!") while on the other hand they insist it won't make a difference ("the government won't get a single penny more from me in taxes.") That doesn't really make a ton of sense.

What it comes down to is that people do, in fact, have the ability to shelter their money from taxation by donating it to charity. The prince in question wants to persuade the Democrat that there's no point in raising his taxes ("the government won't get a single penny") because the cash will all flow to charity instead. But the prince's preference is to keep the low taxes and use his money to finance lavish consumption rather than charitable endeavors. Hence, screw you. In the prince's mental model of congress, members are just greedy bastards seeking to collect as much revenue as possible. But the wise member recognizes that he should by no means be indifferent between the option of the prince buying himself a private jet and the prince financing the expansion of a charter school network or the renovation of an art museum. The consumption of the super-wealthy has an extremely low marginal value, and almost anything else is a socially superior use of resources.

Hence the case for progressive taxation, especially if it can be made progressive taxation of consumption. If what the super-rich come away from is a lot of buildings with their names on it, that's fine by me. The problem is when it all goes toward positional competition and conspicuous consumption.

Women, the 14th Amendment, and the Ambiguity of Intent

Via a justly outraged Kay Steiger, it seems that Antonin Scalia was recently asked his views on whether women deserve the equal protection of the law:

In 1868, when the 39th Congress was debating and ultimately proposing the 14th Amendment, I don't think anybody would have thought that equal protection applied to sex discrimination, or certainly not to sexual orientation. So does that mean that we've gone off in error by applying the 14th Amendment to both?

Scalia's answer is basically that, no, women shouldn't be guaranteed the equal protection of the laws:

[I]f indeed the current society has come to different views, that's fine. You do not need the Constitution to reflect the wishes of the current society. Certainly the Constitution does not require discrimination on the basis of sex. The only issue is whether it prohibits it. It doesn't. Nobody ever thought that that's what it meant. Nobody ever voted for that.

It's amazing to me how often allegedly sophisticated jurisprudence founders on really basic philosophy of language questions. It's probably true that in the subjective understanding of mid-19th century lawmakers "nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws" didn't contradict legal discrimination against women. That's because in some sense they didn't think women were "persons" the same way men are. By the same token, when the framers authorized congress "[t]o establish Post Offices and Post Roads" they obviously didn't intend, as a matter of subjective understanding, to authorize automatic postage stamp dispensers or bridges strong enough to carry trucks. But we understand today that a well-run post office does in fact include stamp machines, computers, and all sorts of other technology that wasn't inside the heads of 18th century constitution writers.

The whole reason human communication is possible is that words have meanings that are independent of the private thoughts of speakers. If you compare a 21st century post office to James Madison's private mental image of a post office, they're totally different. Nevertheless, if you ask whether a 21st century post office is in fact a post office the answer is yes. By contrast, a 21st century sandwich shop is not a post office. By the same token, a given practice either does or does not afford women the equal protection of the law to which they are constitutionally entitled. Asking what someone was thinking about 132 years ago sheds very little light on this question. Probably a 132 years ago, legislators were thinking about the next election!

House GOP Backing Off $100 Billion Spending Cut Pledge

Erik Wasson for the Hill: "The incoming House Republican majority gained power by pledging to cut $100 billion from the federal budget in its first year in power, but aides confirmed Wednesday that this figure is no longer valid."

Their explanation is that when they said "cut $100 billion" they meant "cut $100 billion relative to the baseline in Barack Obama's budget request." But since congress didn't pass the president's budget request, the pledge is now invalid. This is pretty dumb since it's not like the failure to pass the Obama budget is something that suddenly occurred over Christmas weekend. But whatever. Less cutting is better.

What I'm still kind of confused about is what relationship will there be between Paul Ryan's budget proposal and the "budget roadmap" for Medicare privatization that Ryan released last year. Presumably Ryan still believes that privatizing Medicare is the key to long-term fiscal sustainability, and I think it would be instructive to see how many of his colleagues agree with him. At the end of the day, whatever you think of Ryan's idea he's definitely correct that its changes to Medicare and Medicaid over the long term that really matter, not monkeying around with one year worth of discretionary spending.

For and Against China Optimism

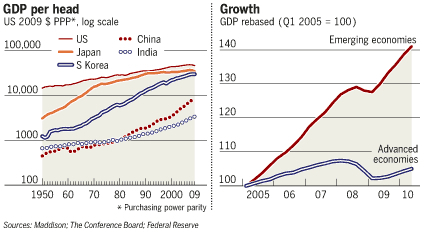

Martin Wolf thinks the past 20 years worth of convergence between the West and the developing world will continue apace:

Until recently, political, social and policy obstacles were decisive. This has not been true for several decades. Why should these re-emerge? True, many reforms will be required if growth is to proceed, but growth itself is likely to transform societies and politics in needed directions. True, neither China nor India may surpass US output per head: Japan failed to do so. But they are far away today. Why should they be unable to reach, say, half of US productivity? That is Portugal's level. Can China match Portugal? Surely.

Of course, catastrophes may intervene. But it is striking that even world wars and depressions merely interrupted the rise of earlier industrialisers. If we leave aside nuclear war, nothing seems likely to halt the ascent of the big emerging countries, though it may well be delayed. China and India are big enough to drive growth from their domestic markets if protectionism takes hold. Indeed, they are big enough to drive growth even in other emerging countries as well.

I like this argument for India, which of course is growing a good deal slower than is China, than I do for China. The reason is that the political risks involved in China continue to seem to me to be very severe. If India's rise is interrupted, it'll be interrupted. But the Chinese political system is a good deal more brittle. A temporary economic contraction could lead to major political chaos and that could lead to anything. You could imagine China being as rich as Portugal in 20 years, or you could imagine China being in one of its sporadic episodes of central government collapse and civil war.

Who Hoovers Whom?

Kevin Drum's sticking to his theory that big finance is stealing our money:

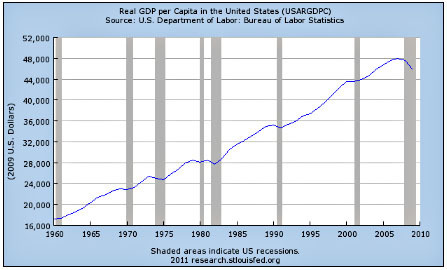

Well then, I have to ask yet again: where is this tsunami of money coming from? If financiers receive a greater fraction of national income than they did in the past, somebody else is getting less. That somebody is almost certainly you and me, whose wages haven't kept up with economic growth, thus creating a huge and growing pool of extra money for the financiers to hoover up.

I continue to think this model is a mistake. A lot of different things have happened over the past thirty years. One is a tendency toward financial deregulation and skyrocketing high-end inequality, and one is a tendency toward median wage stagnation. The former trend is largely concentrated in Anglophone countries, but the latter exists in Japan, Germany, etc., as well.

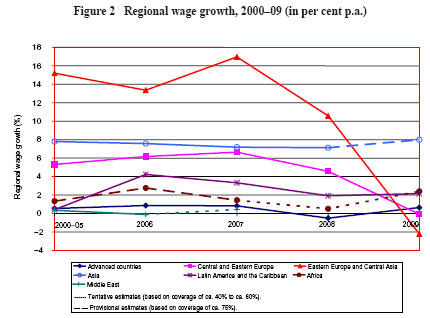

This ILO data only covers ten years, but highlights that wage stagnation is a pretty broad trend:

I think what Kevin's story keeps missing is a plausible causal account of how a tiny number of financiers have been able to hoover up money from the median wage earner. I can tell you a story about how a tiny number of financiers have been able to hoover up money from the executives of rival financial institutions as deregulation has led to consolidation of the industry. I can tell you a story about how a tiny number of financiers have been able to hoover up money from the broad class of rich people in the 80th-99th percentile who own the bulk of the financial assets in the country by swindling them. I can tell you a story about how a tiny number of financiers have been able to hoover up money from the broad class of rich people via the income tax and "bailouts."

But the median wage earner seems harder to me. Especially because they somehow got to the median German wage earner, but not to the median Chinese wage earner.

Here's another story. A lot of the median wage earner's money has been hoovered up by the health care system. If we had single payer health insurance in the United States then increases in per capita health care spending would exhibit themselves as higher taxes. Instead, most people get health care through employers who subsidize their premiums, so increases in per capita health care spending exhibit themselves largely as lower wages. Optimistically, in exchange for all this extra money we're now getting way better health care. Pessimistically (and, I think, more plausibly) an awful lot of it is getting "hoovered up" to little good end.

The last part of my story is monetary policy. It used to be the case that monetary policy errors were two-sided. Sometimes wages grew too fast (inflation) and sometimes they grew too slowly (recession), but since 1980 we've only ever erred in one direction and experienced three labor market recessions and zero outbursts of inflation. In an ideal world, monetary policy never errs and you have neither recessions nor inflation. But if monetary policy errs in an unbalanced direction, how can wage stagnation not result?

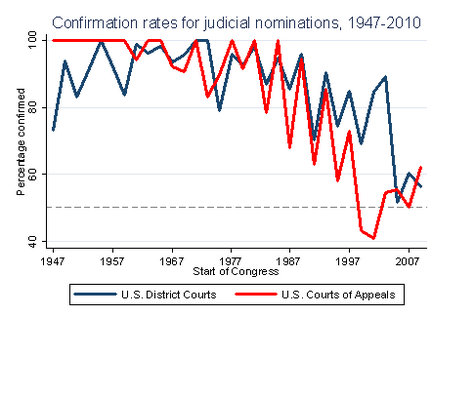

The Plunging Judicial Confirmation Rate

Graphic from Sarah Binder:

It strikes me as obviously undesirable that this this situation persist. In equilibrium, nobody gains an advantage from this back and forth.

January 4, 2011

Endgame

Where are my friends?

— "Lobbying, Rent Seeking, and the Constitution".

— Commander of the USS Enterprise boldly goes too far.

— The least-distinguished Enterprise commander.

— Roads don't pay for themselves.

— Cleveland getting desperate enough to welcome some immigrants.

— The economic impact of robots is a good reason to reorient the tax code around natural resource fees.

— Giving money to poor people is an effective anti-poverty strategy.

Everyone's talking about which songs to play at their aughts nostalgia party. I've got Le Tigre, "Get Off The Internet".

Bringing Balance to Historic Preservation

I was talking to some folks in my condo last night about a construction project just north of our building and I asked what the deal was with an enigmatic derelict warehouse that's adjacent to the construction site:

This, I was told, is owned by a different developer but nothing's being done with it because the building is "for some reason" on the historic preservation list. I asked if there were something we could do to get the building taken off the list, since this listing seemed like the kind of thing that would likely be done by local NIMBY busybodies. Apparently, though, our local Advisory Neighborhood Commission has already asked for delisting but didn't get its way. So the hope was that the construction at the adjacent site would accidentally knock the warehouse down, thus rendering the issue moot.

Relatedly, I was trying to look up more info about this and it turns out that the swathe of broken-down buildings and vacant lots across the street to the south is in fact the "Mount Vernon Triangle Historic District":

If you say so. At any rate, the point I would make about this isn't that historic preservation is never a good idea. All aesthetically meritorious undertakings, including art museums, parks, etc. have some kind of financial cost and it would be a shame to live in a world without aesthetically meritorious undertakings. But if a city or state wants to bear some cost in order to fund a museum, that goes through some kind of appropriation process where the cost is assessed and subject to scrutiny. Historic preservation, by contrast, tends to operate as a kind of ratchet where more and more stuff is added to the list over time and there's little assessment of the overall impact. Then since nobody actually wants to freeze every structure in place, the key issue becomes which people have the right kind of pull or consultants or lawyers or whatever to navigate the process and get things done.

In his forthcoming book, Ed Glaeser proposes the idea of capping the overall number of landmarked buildings in any given city. That way if you want to landmark a new structure, you need to bear a cost—delisting some other structure. The cap could, of course, be raised but that would require a legislative process rather than happening on auto-pilot. I think it's a pretty good idea.

The Eternal Return of Robert Rubin

I'm all for bashing Robert Rubin's tenure at Citigroup or even for bashing some of the financial regulation decisions he made as US Treasury Secretary, but I'm growing frustrated with the widespread use of the term "Rubinite" as essentially a disparaging synonym for "worked on economic policy in the Clinton administration."

The thing about the Clinton administration is that Jimmy Carter's administration ended in 1980. So if you're going to create an economic policy team for Barack Obama your main choices are (1) "folks who worked on economic policy in the Clinton administration," (2) "folks who worked on economic policy in the Bush administration," and (3) "folks with little economic policy experience." Now forced to choose between (1) and (2), I think (1) is clearly the better choice. Option (3) isn't the worst thing in the world, lots of intelligent knowledgeable right-thinking people don't happen to have experience in government. But it seems to me that it's extremely prudent for a president to desire that the majority of his economic policy team be composed of people with previous executive branch economic policy experience. That means basically a lot of "Rubinites" plus various exceptions around the margin. Maybe Obama could recruit Stanley Fischer away from the Bank of Israel to run the National Economic Council. But even so, you'd need a lot of "Rubinites" to staff an administration.

Now if what you're really saying is that you think it's a mistake to believe in the value of previous government experience, that's an interesting argument to have. I think it's wrong but either way it's not really an argument about Bob Rubin.

Alternatively, it could be that what you're really saying is simply that you don't like this revolving door between government and Wall Street. I don't like it either and as Jonathan Bernstein points out there's a simple solution and it involves shifting to a more professional system of government with fewer political appointees. Retired military officers often go work for defense contractors and there's some corrupting influence there, but you don't have a scenario where a Major General retired after the 2000 election, goes to work for Raytheon for eight years, and then comes back as a four-star after Barack Obama's inauguration. Most countries rely on career professionals much more than we do, programs that are managed by civil servants perform better than those run by political appointees, and when it comes to the branch of the public sector that the US takes most seriously—the military—we rely heavily on career professionals. Bernstein has an irrational attachment to America's heavy reliance on political appointees, but as he says "all those appointees need somewhere to go when they're in the out-party." That means a revolving door. I don't like it any more than you—indeed, I like it less and write tedious posts about the need to adopt a system that relies more heavily on civil servants—but it again has little to do with Bob Rubin.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers